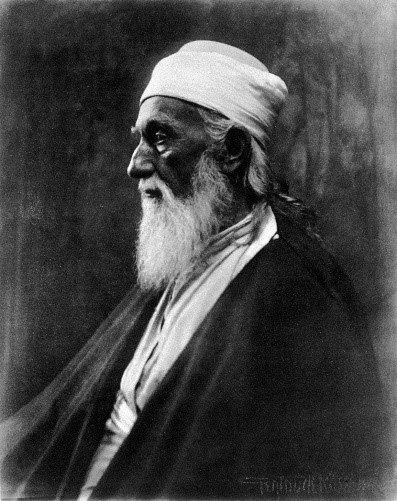

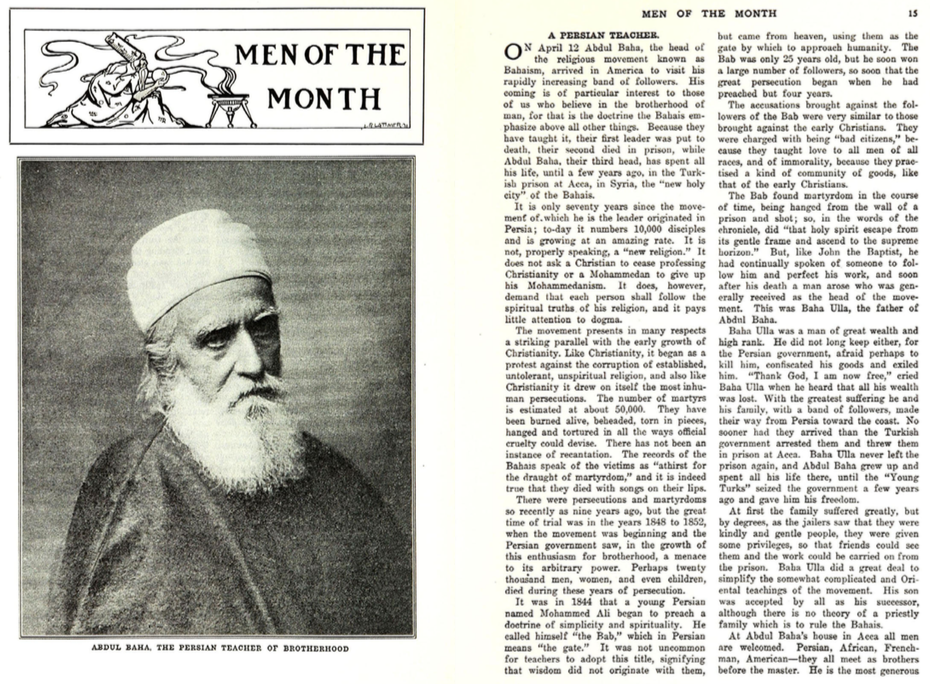

In the late summer of 1911 in the United States, Albert Smiley found a letter sent from Egypt among the items in his mail. Dated August 9, it was from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, head of a religion which Smiley had only briefly encountered the year before.1Two Bahá’ís had attended the 1911 Lake Mohonk Conference and another Bahá’í met Albert Smiley at a different conference in 1911, which may in part explain how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was aware of the annual Lake Mohonk Conferences. Egea, Amin, The Apostle of Peace: A Survey of References to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the Western Press 1871-1921, Volume One: 1871 – 1912, p. 635, note 12. The letter addressed Smiley as the founder and host of the Lake Mohonk Conferences on International Arbitration and praised those gatherings and their goal of establishing arbitration as the means to settle disputes between nations. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated emphatically, “What cause is greater than this!” Explaining how His Father, Bahá’u’lláh, had advocated the unity of the nations and religions, He asserted that the basis of this unity was the oneness of humanity.2“Tablets from Abdul-Baha,” Star of the West, Vol. II, No. 15, December 12, 1911, pp. 3-4. To ensure that His message to the sponsors was received and considered, a second letter was sent on August 22 to the Conference secretary, Mr. C. C. Philips. It began, “The Conference on International Arbitration and Peace is the greatest results [sic] of this great age.”3“Tablets from Abdul-Baha,” Star of the West, Vol. II, No. 15, December 12, 1911, p. 4. In response, the organizers invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to take part in the 1912 Conference and to address one of its sessions.4Egea, Amin, The Apostle of Peace: A Survey of References to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the Western Press 1871-1921, Volume One: 1871 – 1912, p. 302

Even though other groups in the United States and Europe were holding meetings to promote peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá singled out the Lake Mohonk Conferences; for this reason, these exceptional gatherings are worthy of close examination. At them, Albert Smiley and his identical twin brother, Alfred, created an atmosphere that not only illuminated the issue under discussion but resulted in practical action.

The devoutly religious, idealistic Smiley brothers were lifelong members of the Society of Friends, the Christian Protestant denomination better known as Quakers. In their youth, they worked as educators. Then, in 1869, they pursued a different direction by purchasing a dilapidated hunting lodge on the shore of Lake Mohonk in the Catskill Mountains, half a day’s travel by train from New York City, and they successfully developed it into a fashionable resort.

Albert gained a reputation for civic-mindedness and, out of a desire to ameliorate the ills of society, developed a keen interest in social movements. Consequently, Rutherford Hayes, then President of the United States, appointed him to the federal Board of Indian Commissioners. In the course of this service, Smiley recognized an urgent need to create a space where issues regarding America’s indigenous peoples could be explored, and solutions proposed and acted upon. To that end, in 1883, he invited his fellow commissioners and others working on behalf of indigenous populations to his resort for a conference, which proved useful enough to be held annually until 1916. The consultation which occurred during those sessions influenced the course of government policy. Pleased with the success of the Smiley efforts, President Hayes suggested that the brothers establish a similar conference focused on addressing injustices faced by Americans of African descent. The Smileys organized and hosted the first national conference on the situation of Black Americans in 1890, but the extraordinary challenge posed by the issue forced them, with great reluctance, to abandon the conference after just two years.5Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, pp. 30-45.

Unlike many of their fellow Quakers, the Smileys were not strict pacifists; however, their religious upbringing had instilled in them an unshakeable reverence for life.6Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, , p. 5. They were wholeheartedly committed to the cause of peace. Drawing upon what they had learned from experience, in 1895 they established the Conferences on Arbitration at Lake Mohonk. During that first gathering, a standing international court of arbitration was proposed and discussed at length. Among the participants was the man who would serve as head of the US delegation to the conference at the Hague a few years later when the Permanent Court of International Arbitration was established. The exploration of the ins and outs of such a court at Lake Mohonk informed the thinking of many of the participants, especially the American delegation.7Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, pp. 62-63. This would be the first tangible fruit of the arbitration conferences.

Managing two annual conferences, Albert Smiley developed a set of working principles. First, the topic had to be one that could lead to action. One reason the conferences on indigenous populations were influential was that all policy regarding the indigenous peoples in the United States was set by one national government agency, so a handful of officials could implement the recommendations that were made. In contrast, most of the laws and policies that affected the situation of African Americans were set and executed by countless state and local level governments.8Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, p. 40. The issue of international arbitration, while global in scope, shared more in common with the first example because a small number of highly placed politicians, officials, and diplomats determined policy. This meant that the number of people requiring educating and persuading was manageable.

Smiley’s second underlying principle was that religion had a major role to play in resolving social problems, including the promotion of world peace. Religious leaders were invited to take part in all the conferences. The meetings themselves had a religious overtone and the participants were expected to adhere to the Quaker moral code, which included an unwritten prohibition against drinking alcoholic beverages and playing cards.9Davis, Calvin C., “Albert Keith Smiley”, Harold Josephson, editor, Biographical Dictionary of Modern Peace Leaders, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1985, p. 889.

The Smileys also learned how to conduct consultation effectively. A variety of points of view were welcome and fostered, and Albert chose chairmen who would not use their role to promote their own viewpoints or agendas and would be even-handed. The Smileys ensured that no group or position dominated the discussion portions of the sessions. Discussion was to be conducted at the level of principle rather than based upon specific matters, especially those that were controversial, such as the Spanish American War. The Smileys did not allow speakers at the arbitration conference to give talks about the horrors of war, lest the consultation become less about solutions and more about sentiment. The conferences were, however, an opportunity to provide information about legislation, treaties, and other news related to the topic at hand.

At the outset, idealistic leaders of social movements whose worldviews were not always practical filled the arbitration sessions, so the Smileys began to invite representatives of the business community. Nothing was worse for the average businessman than the economic disruption and uncertainty of a war. Women were always invited and fully participated, which was liberal for the time.

Finally, Albert Smiley recognized that the conference schedule must allow time for informal meetings and the networking that naturally occurs through socializing. The plenary sessions only lasted two hours in the morning and two hours in the evening, with the rest of the day unscheduled except for meals. The expansive property, much of which was woodlands with hiking trails surrounding the lake, provided welcome opportunities both to meditate in nature and to discuss ideas privately.10For a lengthy discussion of how the conferences were conducted, see Burgess, pp. 61-67.

By the time ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote to the organizers of the conferences, the gatherings had become influential. The groundwork necessary for the establishment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague, for instance, was established there, and the American Society of International Law was also created at the conference, in the 1905 session.11For a brief discussion of the fruits of the Lake Mohonk Arbitration Conferences see Burgess, p. 890.

Establishing the Court of Arbitration was only the beginning, for as that institution undertook its work, other issues arose: How could countries be encouraged or required to bring matters to the Court rather than resort to war? How were the decisions of the Court to be upheld? Treaties became an obvious instrument and topic for discussion. Because the conferences were held annually with many of the same participants, different layers of the matter of arbitration were explored over their 21-year history.

When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed the conference as its opening speaker on the evening session on May 15, 1912, He was introduced by the conference chairman, Nicholas Murray Butler, President of Columbia University, who would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Among the approximately 200 people in attendance were the future Prime Minister of Canada, W. MacKenzie King, ambassadors, jurists, journalists, academics, religious leaders, businessmen, trade unionists, and leaders of civic organizations, including peace activists. The speakers who followed Abdu’l-Bahá that evening came from Nicaragua, Argentina, Germany, and Canada—a sampling of the many countries represented.12Report of the Eighteenth Annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, Published by the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, 1919, pp. 42 – 63.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá was allotted twenty minutes for His talk, most of which was in the form of reading a previously submitted English translation. His address began with a discussion of Bahá’u’lláh’s emphasis on the oneness of humanity and His promise of the coming of the “Most Great Peace.” He explained to the audience that Bahá’u’lláh promulgated His Teachings during the nineteenth century when wars were raging throughout the world among religious sects, ethnic groups, and nations. His Father’s teachings, explained ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, inspired many people to put aside their prejudices and instead love and closely associate with their former enemies. The talk then turned to the importance of investigating reality and forsaking blind imitation; for, as He pointed out, once people see truth clearly, they will behold that the foundation of the world of being is one, not multiple. Following His discussion of the oneness of humankind, He explored the agreement of science and religion. Throughout the speech, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stressed that religion should bring about a bond uniting the peoples of the world, not be the cause of disunity; that all forms of prejudice must be abolished, including racial, religious, national, and political; and that women should be accorded equal status with men. He then briefly touched upon the problem of the disparities of wealth and poverty. Finally, He stated that philosophy is incapable of bringing about the absolute happiness of mankind: “You cannot make the susceptibilities of all humanity one except through the common channel of the Holy Spirit.”13Report of the Eighteenth Annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, Published by the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, 1919, pp. 42 – 44.

The members of His entourage recorded that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talk was well-received and that many people approached Him afterward to thank Him and to speak with Him.14Mahmud’s Diary, p. 101. Note that the chronicler, Mahmud, was confused about the dates. The full translation of His talk was included in the widely distributed report of the conference and much of the press coverage also mentioned it.15The conference published an annual report which was sent to all libraries across the United States with more than a 10,000 book collection (the average size of a small community or branch library). Burgess, p. 65. One of the promoters of the conferences was the wealthy industrialist, Andrew Carnegie, who establishing public libraries across the United States as well as for the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. (There are indications that Carnegie was present when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at Lake Mohonk, but that is unconfirmed.) For a thorough accounting of the press coverage of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s participation in the 1912 conference, see Egea, pp. 306. Press accounts of His arrival in the United States also frequently made mention of His intention to participate in the Lake Mohonk Conference. Ibid, pp. 197, 198, 201, 203, 217, 286, 298, 299.

Earlier that day, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had taken advantage of the unscheduled afternoon to give at least one informal talk and to speak with a number of the conference participants. He did not stay for the entire event but returned to New York the following morning after spending His last hours at the resort visiting with Albert Smiley.16Mahmud’s Diary, pp. 102 – 103.

The 1912 conference was the last one attended by the far-sighted Albert Smiley. Alfred had already passed away and Albert followed his twin in December of that year. Their brother, Daniel, whose attention to detail in planning the conferences was part of their success,17Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, p. continued to host the conferences until circumstances forced him to discontinue them when the United States entered WWI in 1917. Years later, Dr. Butler, reviewing his own participation in the conferences between 1907 and 1912, reflected, “it is extraordinary how much vision was there made evident.” However, he concluded, “it is more than pathetic that that vision is still waiting for fulfilment.”18Butler, Nicholas Murray, Across the Busy Years: Recollections and Reflections II, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1940, p. 90.

All the efforts of peace organizations and gatherings such as the Lake Mohonk Conferences culminated in the creation of the League of Nations at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. However, although President Woodrow Wilson was given credit for conceiving the League, the US Congress refused to ratify the treaty that would make the United States a member. Thus, despite hopeful expectations, the League was born handicapped and, after a few initial achievements, proved to be ineffective at preventing wars. It was, nevertheless, a beginning.

Following the Great War, the United States returned to its default foreign policy position of isolationism; namely, the conviction that the country should stay out of the conflicts afflicting other parts of the world. It was as if all the work done before the war to promote world peace through internationalism had been undone. This situation was exacerbated by the 1919 “Red Scare,” during which anarchists and communists were accused of instigating several violent incidents. Moreover, in the 1920s, deep-seated prejudices took firmer hold of US public policy. Congress passed restrictive immigration legislation in 1924 to keep out Jews and Catholics. It became all but impossible for Africans to legally immigrate, and Chinese immigration was banned by law.

Meanwhile, in 1919, white people attacked and set fire to black neighborhoods in Chicago and, in 1921, attacked and even bombed from the air a prosperous black district in Tulsa, Oklahoma, leaving untold black citizens dead and the lives of the survivors ruined. The white supremacist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic organization, the Ku Klux Klan, experienced a resurgence, demonstrating its strength with a large parade through Washington, D.C. in 1926, its members’ distinctive white-hooded uniforms blending with the backdrop of the gleaming white marble of the U.S. Capitol building.

On the international front, fascism and communism arose quickly from the still-smoldering ashes of Europe. The armistice of 1918 would prove to be only an intermission before war erupted again in the 1930s. In the Far East, Japan’s armies were on the move, beginning with the 1931 invasion of the Manchurian region of China. In country after country, rearmament accelerated. If ever the peoples of the world needed to grasp Bahá’u’lláh’s message that humankind is one, it was during the period between the World Wars.

World peace remained the primary focus of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talks when He visited California a few months after His appearance at the Lake Mohonk Conference. In a talk given at the Hotel Sacramento on 26 October 1912, He said that “the greatest need in the world today is international peace,” and after discussing why California was well-suited to lead the efforts for the promotion of peace, He exhorted attendees: “May the first flag of international peace be upraised in this state.”

One of those inspired by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision of California as a leader in the promotion of world peace was Leroy Ioas, a twenty-six-year-old resident of San Francisco and rising railway executive. He remembered how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had met with many prominent people during His ten months in the United States and, drawing upon His example, some years later Ioas became determined that Bahá’í principles should be widely promulgated among community leaders, especially those in positions to put them into effect or to influence the thinking of the citizenry. In 1922, Ioas wrote to Agnes Parsons in Washington, DC, to solicit her opinion and guidance about the prospect of a unity conference in his city. The previous year, at the express request of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, she had organized a successful, well-attended Race Amity Conference in her own racially polarized region of the South. Ioas noted in his letter that the challenge on the West Coast was not simply prejudice towards black people, for their numbers were few, but strong animosity towards the more numerous Chinese and Japanese citizens. Parsons responded with encouragement and suggestions. Armed with this guidance, Ioas approached two of the pillars of the Bay Area Bahá’í community—Ella Goodall Cooper and Kathryn Frankland—to gain their support for a conference. With this groundwork laid, he proposed a unity conference to the governing council for the San Francisco Bahá’í community, which decided it was not timely.

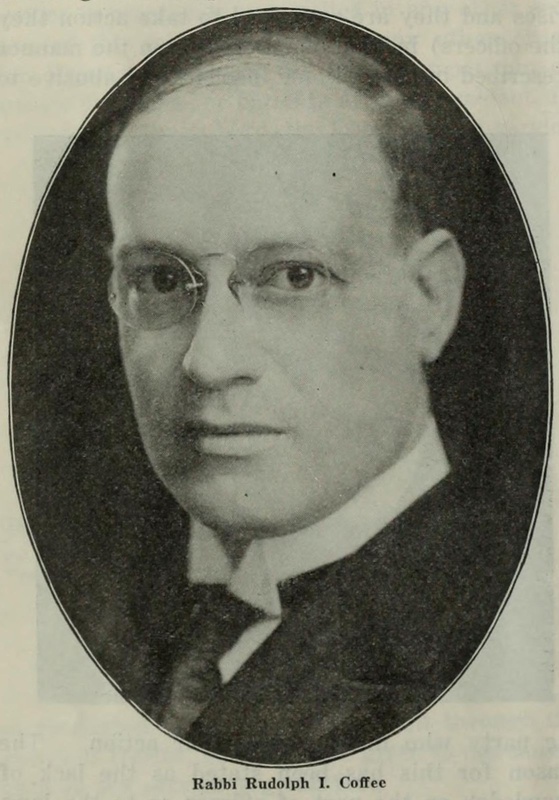

Undeterred, Ioas approached Rabbi Rudolph Coffee, head of the largest synagogue in the Bay Area and the first Jewish person to serve as chaplain of the California State Senate. Coffee shared many of the Bahá’í ideals and became an enthusiastic ally. Ioas again turned to the Bahá’í council, and this time it supported his plan to form a committee that included Cooper and Frankland as members.

The committee’s first order of business was to draft a statement of purpose. It said that the goals of the conference were “to present the public … the spiritual facts concerning the beauty and harmony of the human family, the great unity in the diversity of human blessings, and the harmonizing of all elements of the body politic as the Pathway to Universal Peace.” The group also decided that the expenses of the three-day conference set for March 1925 would be covered by the Bahá’í community so that participants would not be asked to contribute money—but, despite the Bahá’í underwriting of the event, the program would not have any official denominational sponsorship. The committee booked the prestigious Palace Hotel, the city’s first premier luxury hotel, as the venue for the event.

Cooper, listed on the San Francisco Social Registry,191932 San Francisco Social Registry, https://www.sfgenealogy.org/sf/1932b/sr32maid.htm. The social registry is a directory of socially-connected members of high society. had access to the leading citizens of the area. As experienced event organizers, Cooper and Frankland set to work soliciting leading city residents to serve as “patrons”. The greatest coup was enlisting Dr. David Starr Jordan, founding president of Stanford University, to serve as the honorary chairman of the conference. Jordan had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and was known in peace movement circles for having developed his own peace plan. Other note-worthy speakers accepted, and the first World Unity Conference was born. The committee even hired a public relations firm to advertise the event and assist with arrangements.

Over the course of the evenings of March 21, 22, and 23, speakers addressed, before large audiences, the issues of the status of women and of the black, Chinese, and Japanese communities, as well as topics related to world peace. The roster of accomplished presenters included not only Rabbi Coffee and Dr. Jordan but also the senior priest of the Catholic Cathedral, a professor of religion, a Protestant minister of a large African-American congregation, distinguished academics, and a foreign diplomat. The last one to address the conference was the Persian Bahá’í scholar, Mírzá Asadu’llah Fádil Mázandarání, the only Bahá’í on the program.

Measured by attendance and favorable publicity, the conference was an unqualified triumph. But as the last session drew to a close, the inevitable question was put to Ioas by Rabbi Coffee: What next? Hold such a conference annually? The planners did not have an answer. Just like the Smileys, Rabbi Coffee realized that the conference should lead to action. Undertaking one conference had stretched the financial and human resources of the San Francisco Bahá’í community. It had also provided a glimpse of what they could achieve. The ideas presented were, however, scattered to the wind with only the hope that some hearts and minds had been changed.20Chapman, Anita Ioas, Leroy Ioas: Hand of the Cause of God, pp. 45-49.

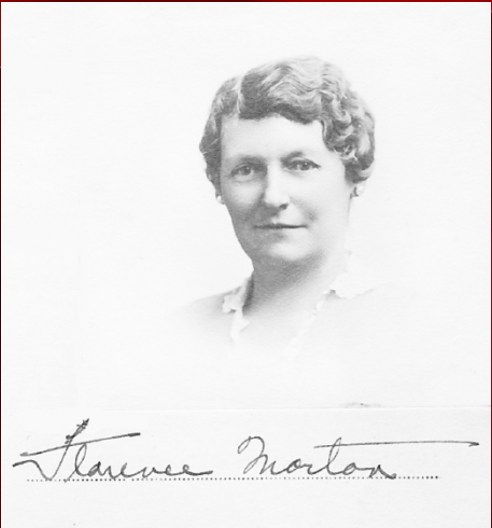

Ioas provided the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada—the governing council for the Bahá’í communities of the two countries—with a report, and he suggested that similar World Unity Conferences be held in other communities. The National Assembly enthusiastically agreed and established a three-person committee, including two of its officers, to assist other localities in their efforts to hold conferences. The committee members were Horace Holley, Florence Reed Morton, and Mary Rumsey Movius.21Bahá’í News Letter: The Bulletin of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, no. 12, June-July 1926, pp. 6-7. Human resources and all funds were to come from the sponsoring communities, but the national committee would help to promote the conferences and offer other assistance, including speakers.

During 1926 and into 1927, eighteen communities held World Unity Conferences. These included Worcester, Massachusetts; New York, New York; Montreal, Canada; Cleveland, Ohio; Dayton, Ohio; Hartford, Connecticut; New Haven, Connecticut; Chicago, Illinois; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Buffalo, New York. They followed the format of the San Francisco conference with three consecutive nights of programs featuring a diversity of speakers—the majority of whom were not Bahá’ís—on topics that were encompassed within Bahá’í principles. Among the presenters were clergy, academics, politicians, including the first woman to serve in the Canadian Parliament,22This was Agnes Macphail, who spoke at the Montreal Conference which was chaired by William Sutherland Maxwell. Nakhjavani, Violette, The Maxwells of Montreal : Middle Years 1923-1937, Late Years 1937-1952, George Ronald, Oxford, p. 74.22 and writers. Some conferences were held in church buildings, others on university campuses, and a few in hotels.

As in San Francisco, the World Unity Conferences provided valuable experience that enhanced the capacities of the hosting Bahá’í communities. They supplied a means for those fledgling communities to obtain positive local publicity and brought the nascent Faith to the attention of civic leaders as a new and growing force for good. Although the conferences were on the whole successful, as in San Francisco, they stretched to the limit local human and material resources. Shoghi Effendi urged the American community to follow-up with the conference attendees who showed the greatest interest,23Shoghi Effendi, Bahá’í Administration: Selected Messages 1922 – 1932, p. 117. but this guidance was not implemented systematically.

As the series of conferences drew to an end and attention turned to other matters, a growing sense of urgency motivated the three committee members because they took to heart ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s warning that another war greater than the last one was coming; they hoped that bringing the Bahá’í message to the attention of important people might prevent it.24Horace Holley fled Paris, France with his wife and young child at the beginning of WWI in September 1914 and so keenly understood the significance of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s prediction that another war was coming in His second Tablet to the Hague, written after the Great War. Letter from Horace Holley to Albert Vail, October 21, 1925, Vail papers, U.S. Bahá’í National Archives. Mary Movius, in discussing Dr. Randall’s upcoming role as primary spokesman for the World Unity Foundation with him, mentions her concern about where the coming war will start. Letter from Mary Movius to John Randall, June 11, [1927?], U.S. Bahá’í National Archives. They devised a plan to establish a World Unity Foundation that would both sponsor ongoing conferences and provide speakers to other events. In addition, they decided to create a proper organization—a movement—with local councils and a journal titled World Unity. The National Spiritual Assembly approved of the proposal but decided that it should be an individual initiative rather than an official activity of the Faith. The Assembly also encouraged the Bahá’í community to be supportive of the Foundation.25Bahá’í News Letter: The Bulletin of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, no. 20, November 1927, p. 5.

Each of the three members26Montfort Mills, a lawyer from New York City and former chairman of the National Spiritual Assembly was also part of this consultation, but at the time he was engaged in frequent travels abroad on behalf of the work of the Faith. As much as possible, Mills served as an advisor to and promoter of the World Unity Foundation. made important contributions to the new endeavor.

Morton, a prosperous businesswoman who owned a factory, provided most of the funding and served as treasurer. Holley, with a professional background in writing, publishing, and advertising, assumed the management of the journal. Movius, a writer and another source of funds, became president of the board of directors. They hired Dr. John Herman Randall, an ordained Baptist minister and associate pastor of a non-denominational, liberal church—The Community Church in New York City—to be the Foundation’s public face as director and editor.27Randall was one of the two Christian clergymen from New York City who played active roles in the Bahá’í community during the 1920s and 1930s. Shoghi Effendi said, “I am delighted to learn of the evidences of growing interest, of sympathetic understanding, and brotherly cooperation on the part of two capable and steadfast servants of the One True God, Dr. [John] H. Randall and Dr. [William Norman] Guthrie, whose participation in our work I hope and pray will widen the scope of our activities, enrich our opportunities, and lend a fresh impetus to our endeavors.” Bahá’í Administration, p. 82. For a brief summary of Randall’s life see, Day, Anne L., “Randall, John Herman”, Kuehl, Warren F., editor, Biographical Dictionary of Internationalists, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1983, pp. 595 – 97. See also, “John Herman Randall Sr.: Pioneer liberal, philosopher, pacifist” by one of his grandsons [David Randall?] at http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~knower/genealogy/johnhermansrcareer.htm. Randall was a gifted, widely sought-after orator and author who was keenly interested in and sympathetic towards the Bahá’í Faith, even though he was not a professed adherent. Randall had spoken at several of the World Unity Conferences and shared the ideals underlying them. The four individuals then established a non-profit corporation, the World Unity Foundation, with Randall as director and journal editor.28The Board of Trustees of the World Unity Foundation included the following Bahá’ís: Horace H. Holley, Montfort Mills, Florence Reed Morton, and Mary Rumsey Movius. The other members were: Reverend John Herman Randall (non-denominational Protestant), Reverend Alfred W. Martin (Unitarian), and Melbert B. Cary (friend of Dr. Randall). The Honorary Committee for the Foundation were: S. Parkes Cadman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Rudolph I. Coffee, John Dewey, Harry Emerson Fosdick, Herbert Adams Gibbons, Mordecai W. Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Rufus M. Jones, David Starr Jordan, Harry Levi, Louis L. Mann, Pierrepont B. Noyes, Harry Allen Overstreet, William R. Shepherd, Augustus O. Thomas. Bahá’í News Letter: The Bulletin of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, no.22, March 1928, p. 8.

The original plan was that Dr. Randall, working full time for the Foundation, would ensure that World Unity Conferences were held all over the country. The talks from those events would provide the content for the journal, and conference participants would be encouraged to form local councils to carry forward the work of spreading the cause of peace. None of this went as planned, despite a few early successes. Speakers rarely followed through with written versions of their talks. Local committees often dissolved within a year. Limited resources made it impossible to give attention to the innumerable details required to attract and retain a growing membership.29Letter dated July 7, 1932 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, U.S. Bahá’í Archives.

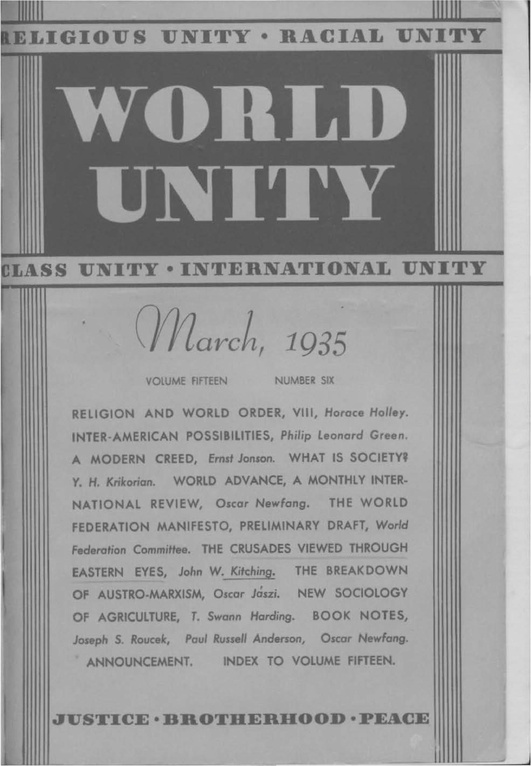

Despite setbacks associated with the conferences, in October 1927, the first issue of World Unity was published, providing an expansive view of the world and current international affairs. It covered not only important peace subjects such as the League of Nations and the Paris (Kellogg-Briand) Pact of 1928—the first attempt to make war illegal—but also articles introducing to the Western reader various countries, religions, arts, and other topics that would engender a sense of world citizenship. The contributors by and large were not Bahá’ís, though the three Bahá’í directors tried to ensure the publication reflected Bahá’í ideals. A number of those featured in its pages had been regular participants at the Lake Mohonk Arbitration Conferences, including leading peace activists Hamilton Holt, Edwin D. Mead and Lucia Ames Mead, and Theodore Marburg. A small number had spoken at World Unity Conferences, among them Dr. Jordan and Rabbi Coffee. Though the majority of articles were written specifically for the magazine, some were taken from speeches or other publications. Over seven years, the magazine published articles by notables such as Nobel Peace Prize recipient Norman Angell; eminent sociologist and advisor to President Wilson, Herbert Adolphus Miller; scholar of international law Philip Quincy Wright; the foremost scholar on auxiliary languages, Albert Léon Guérard, who heard ‘Abdu’l-Bahá speak in California; the first president of the Republic of Korea, Syngman Rhee; the well-known writer and philosopher Bertrand Russell; eminent U.S. foreign policy historian and official historian of the San Francisco Conference to establish the United Nations, Dexter Perkins; Charles Evans Hughes, chief justice of the US Supreme Court; philosopher and influential social reformer John Dewey; socialist, pacifist, and US presidential candidate Norman Thomas; Philip C. Nash, executive director of the League of Nations Association; and Robert W. Bagnell, a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the preeminent American civil rights organization. The journal occasionally carried talks by or about the teachings propagated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed one version of the masthead and also penned an article.30Frank Lloyd Wright was a friend of Horace Holley, who convinced Wright to submit an article. Wright then suggested that he redesign the magazine’s cover. His design, with some modifications, was first used for the October 1929 edition of World Unity. Website: The Wright Library, http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Periodicals/1930-39.htm. (The article quoted on the website assumes that Holley and Wright met through their mutual friend, Dr. Guthrie. Actually, they first met in Italy in 1910. (Letter from Horace Holley to Irving Holley from Florence, Italy, dated Easter Sunday [1910], in the possession of the author.)) But perhaps one of the most praiseworthy attributes of the journal was its inclusion of well-reasoned articles by ordinary people who would have not found another national outlet for their voices.31Day, Anne L., “Randall, John Herman”, Kuehl, Warren F., editor, Biographical Dictionary of Internationalists, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1983, pp. 100-101.

There were two aspects of the work of the Foundation that proved problematic. First, the objectives were lofty, but too broad. For example, the journal’s subhead was: “A monthly magazine promoting the international mind.” This allowed for wide participation in the Foundation’s work, but it also left ambiguous the question of what exactly the journal stood for. In 1932, the Foundation sought to bring greater clarity to this question, first by explicitly promoting the Bahá’í concept of world federation and then by adopting the tenets set forth in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s 1919 letter to the Central Organisation for Durable Peace in The Hague.

A second challenge was that the initial approach taken by the Foundation confused and dismayed many Bahá’ís. In the beginning, the founders were concerned that associating the World Unity Foundation explicitly with religion would turn away some people who otherwise shared Bahá’í ideals and would cause their primary target audience, leaders of thought, to ignore its activities. In fact, the Bahá’í background of the Foundation was so well-concealed that most who have written about it after it was discontinued have also believed that Dr. Randall was its sole founder and proponent. 32Most of what is published about Dr. Randall’s work with the World Unity Foundation is derived from memorials to him written by his descendants or from his own books. To address the confusion that had arisen, the magazine began in 1933 to include articles explicitly based on the Bahá’í Faith.33The decision to make the magazine more openly Bahá’í was taken in 1932. Letter dated October 28, 1932 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, page 2, U.S. Bahá’í Archives. In a 1933 letter to Morton, Holley pointed out to her how he was trying to “build a bridge of sympathetic understanding between World Unity readers and the Articles of the Cause which will be published later on” through his more recent editorials. Letter dated February 2, 1933 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, page 2, U.S. Bahá’í Archives. See also an explanation of the careful transition to Bahá’í content in letter dated January 7. 1933 from Horace Holley to Mary Movius, U.S. Bahá’í Archives. During its last years of publication, it was openly a Bahá’í journal.

Because of the controversy the Foundation generated within the Bahá’í community, Shoghi Effendi addressed the matter in a letter to the National Spiritual Assembly, discussing at length the approach of putting forth the Bahá’í message without mentioning the source of the ideas. Referring to the World Unity Conferences held earlier by Bahá’í communities, he wrote, “I desire to assure you of my heartfelt appreciation of such a splendid conception.” He then explored why a variety of approaches, both direct and indirect, to conveying the teachings of the Faith were appropriate and desirable if executed with thoughtful care under the supervision of a National Spiritual Assembly.34Shoghi Effendi, Bahá’í Administration, pp. 124 -28.

Just as the Foundation and its journal were gaining traction, they encountered one challenge that could not be overcome: The Great Depression of the 1930s. Morton could no longer pay her factory employees, much less continue to fund the organization. Movius experienced her own economic setbacks. Randall resigned at the end of 1932. In a last effort to save the journal, Holley took over as editor.35Both Randall and Holley were paid for their services, but after the financial crisis started, Holley took a cut in salary even as his responsibilities increased. For a time, he drew no pay but funded the journal from his own savings. Letter dated April 1, 1933 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, U.S. Bahá’í National Archives. But the times were against it. The world’s rapid march towards war was already underway. Peace movements seemed out of touch and magazines promoting their ideals became a luxury. No matter the sacrificial strivings of the proponents of the World Unity Foundation, their resources proved insufficient to further any interest that had been generated. As Movius wrote to Holley, “I like extremely the editorials you are writing for ‘World Unity,’ and only hope they will bear fruit. They will, undoubtedly, even if we never hear of it.”36Both Randall and Holley were paid for their services, but after the financial crisis started, Holley took a cut in salary even as his responsibilities increased. For a time, he drew no pay but funded the journal from his own savings. Letter dated April 1, 1933 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, U.S. Bahá’í National Archives.

Finally, in 1935, after consulting the institutions of the Bahá’í Faith, it was decided to merge World Unity with another publication, Star of the West (renamed The Bahá’í Magazine in its later volumes) to become a new entity, World Order.37Bahá’í News, no. 90, March 1935, p. 8. This magazine was published from 1935 to 1949, revived in 1966, and ran until 2007. Like World Unity, its erudite articles covered a wide range of topics aimed at the educated public, but it was unmistakably a Bahá’í organ under the auspices of the US National Spiritual Assembly and never acquired as broad a readership as World Unity.

Did the World Unity Foundation and its journal have any impact? The renowned head of the Riverside Church in New York City, Harry Emerson Fosdick, said of World Unity Magazine that it represented, “one of the most serious endeavors … to use journalism to educate the people as to the nature of the world community in which we are living.”38Undated World Unity circular. U.S. Bahá’í Archives. Perhaps the foremost scholar of internationalism during the early twentieth century, Warren F. Kuehl, listed the magazine as one of only a tiny handful at the time discussing issues promoting peace through international order, noting that it seemed unique in its advocacy of a world federation.39Kuehl, Warren F. and Lynne Dunn, Keeping the Covenant: American Internationalists and the League of Nations, 1920-1939, Kent State University Press, 1997, p. 73 Another scholar of diplomatic history, Anne L. Day, concluded that World Unity’s primary contribution was creating a space for lesser-known people interested in international peace to put forth their ideas.40Kuehl, Warren F. and Lynne Dunn, Keeping the Covenant: American Internationalists and the League of Nations, 1920-1939, Kent State University Press, 1997, pp. 100-101

… the conferences and the magazine helped foster a world outlook without prejudice and a faith in humanity which survived the horrors of World War II. World Unity Magazine gave young scholars a medium to which they could hone their insights toward global humanitarian values, thus broadening consciousness to recognize the moral and spiritual equality, “to realize that the interests of all men are mutual interests.”41Day, Anne L., “Randall, John Herman”, p. 596.

The World Unity Foundation was formally dissolved just as armies were moving into a growing number of hot spots in Europe and Asia. Within a few short years, much of the globe would be plunged into the most horrible conflict mankind had ever known. As the end of World War II came into view, a few far-sighted leaders became determined that such a catastrophe should never afflict humanity again and looked to the future. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for an international conference to be held in October 1945 to create a new organization of countries that would improve upon the impotent League of Nations. The United Nations would be born that year.

That historic conference was held in San Francisco, fulfilling ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s wish that California would be the first place to hoist the banner of international peace. Seated in the audience were official representatives of the worldwide Bahá’í community, including Holley’s close friend and protégé, Mildred Mottahedeh, who would later serve as the Faith’s representative to the United Nations. Indeed, from the very inception of the United Nations, the Bahá’í International Community (BIC) has actively participated in its work as an official non-governmental organization.

Those representing the Bahá’í Faith to the United Nations and its agencies are building on the foundation laid by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’ over a century ago, drawing on His example and the lessons that have been learned since. First and foremost, they have been guided by the conviction that all participation in endeavors to remedy the ills of humanity should be based on moral and spiritual principles. This precept applies to the design, implementation, and evaluation phase of any initiative. Discussing difficult issues by first identifying underlying principles naturally enhances unity and understanding. Furthermore, over the course of the past century, Bahá’ís have consistently fostered the broad inclusion of voices in public discourse, enabling the diverse voices of humanity to contribute, on equal footing, to those discussions that impact the great issues of the day.

This deliberate approach, along with always adhering to the attributes of trustworthiness, inclusiveness, and dependability, has gained the BIC a positive reputation among Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). In 1970, the BIC representative was elected to serve on the Executive Board of the United Nations Conference of Non-Governmental Organizations. Subsequently, Bahá’í representatives have been elected or appointed to officer positions on a number of significant NGO committees and advisory bodies to the United Nations, often serving as chairpersons, such as the election of BIC Representative Mary Power as Chair of the NGO Commission on the Status of Women from 1991-1995.

The BIC’s wide-ranging engagement in the world’s most pressing issues has not gone unnoticed. As early as 1976, Kurt Waldheim, then United Nations Secretary-General, addressed the Bahá’í community with the following statement:

Non-governmental organizations such as yours, by dealing comprehensively with the major problems confronting the international community and striving to find solutions which will serve the interests of all nations, make a very substantial and most important contribution to the United Nations and its work.42In a message dated 1 June 1976 to the International Bahá’í Conference in Paris. Available at https://www.bic.org/timeline/international-bahai-conference-paris

In 1987, Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar designated the BIC as “Peace Messengers,” an honor bestowed upon only three hundred organizations. Approaching the turn of the century, Secretary-General Kofi Annan called for both a Millennium Summit for the leaders of the world and a Millennium Forum for the world’s peoples, represented through non-governmental agencies. In recognition of its consistently principled approach to its work, its integrity, and its even-handedness, the BIC was chosen to co-chair the Forum and to provide the speaker from the Forum to address the Summit.

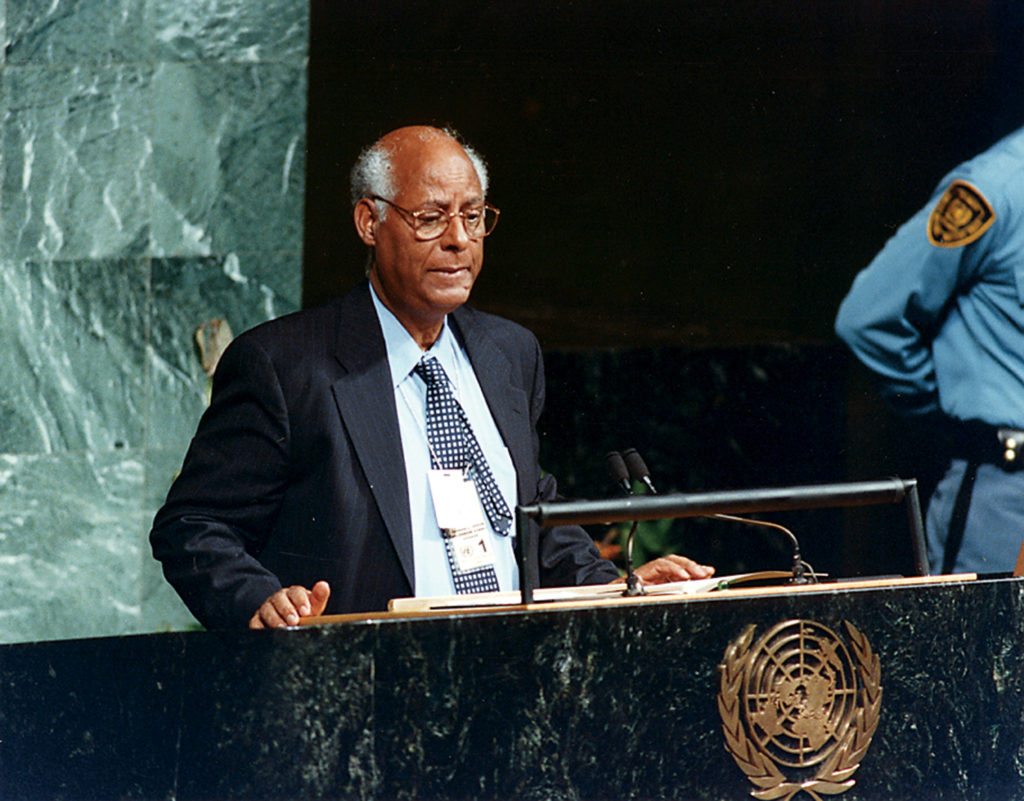

On September 8, 2000, Dr. Techeste Ahderom, then the BIC Principal Representative to the United Nations, addressed the assembled heads of state of more than 150 nations on behalf of the peoples of the world.43The Four Year Plan and The Twelve Month Plan, 1996 – 2001: Summary of Achievements, Bahá’í World Center, 2002. In his talk, Ahderom reminded the assembled leaders that the very idea of the League of Nations and, later, the United Nations, arose through the participation of civil society in various forms. He closed with the words from the Millenium Forum Declaration: “‘In our vision we are one human family, in all our diversity, living on one common homeland …’”44https://www.bic.org/statements/statement-millennium-summit

As resources have allowed and capacity has increased, the BIC has addressed vital issues including racial discrimination, human rights, the status of women, protection of the environment, science and technology, the rights of indigenous peoples, education, health, youth, freedom of religion or belief, global governance, and UN reform.

According to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in His address at Lake Mohonk, the issue of peace is multifaceted, and it will not be attained until an environment is created that will ensure a lasting end to conflict. In its approach to the promotion of peace, the Bahá’í community has always sought a holistic approach to the question of global peace. In this light, the BIC New York Office in 2012 instituted a regular forum where ideas could be discussed freely, on the condition that the identity of the person or organization offering the information is not disclosed. Participants in these forums have thereby, regardless of their functions and roles, had the freedom to engage in consultation without it being assumed that their comments represent the official position of their country or organization. By mid-2020, more than sixty of these discussions had been held covering a wide range of topics.45Berger, Julia, Beyond Pluralism: A New Framework for Constructive Engagement (2008 – 2020), chapter 7, pp. 16 19. Pre-publication edition. I am grateful to Julia Berger and Melody Mirzaagha, for staff members of the Bahá’í International Community Offices in New York for their assistance and insights. I also wish to thank the BIC New York Office for directing me to Dr. Berger and Ms. Mirzaagha. Through this and many other efforts, the BIC has been learning to draw on the unseen power of consultation to create environments where those entrusted with global leadership and whose decisions impact the fortunes of the planet are able to deliberate in a distinctive environment on the major issues of our time.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations, the BIC issued a statement asserting that to meet the needs of the twenty-first century will require a far greater level of global integration and cooperation than anything that has existed before.46In 1995, a statement titled “Turning Point for All Nations” was issued for the 50th Anniversary of the United Nations. It is available at https://www.bic.org/statements/turning-point-all-nations The statement calls for the strengthening and evolution of the consultative process of international dialogue and for world leaders to give priority to that which will benefit the whole of humankind. It argues that what is needed now is a radical change in the approach to solving the problems of the world—a process that conceives of the world as an organic whole and takes into consideration the essential need for spiritual and ethical advancement to be commensurate with scientific and technological progress.47“A Governance Befitting: Humanity and the Path Toward a Just Global Order”, A Statement of the Bahá’í International Community on the Occasion of the 75th Anniversary of the United Nations, p. 5. https://www.bic.org/sites/default/files/pdf/un75_20201020.pdf

Ultimately, the goal of the Bahá’í Faith is to bring about a universal recognition that we are all one people—with the profound implications that carries through all areas of life, requiring no less than a restructuring of society. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá through His words and actions pointed out the way to promote this most essential of all truths, and a clear thread can be seen from His contributions to peace to the efforts of the Bahá’í community since. Such efforts will doubtless continue for decades, perhaps centuries, until the time arrives when all decisions will rest upon the indisputable reality of the oneness of humankind and the world will transform into a new world—a peaceful world where war is relegated to the sad accounts found only in history books.

Once again, as the United States finds itself embroiled in racial conflicts and decades-old struggles for racial justice and racial unity, the Bahá’í community of the United States stands ready to contribute its share to the healing of the nation’s racial wounds. Neither the current racial crisis nor the current awakening is unique. Sadly, the United States has been here before.1National Advisory Committee Report on Civil Disorders (New York: Bantam Books, 1968). The American people have learned many lessons but have also forgotten other lessons about how best to solve the underlying problems facing their racially polarized society. For decades the country has seen countless efforts by brave and courageous individuals and dedicated organizations and institutions to hold back the relentless tide of racism. Many of these efforts have achieved great outcomes, but the tide has repeatedly rushed back in to test the resolve of every generation after the fall of Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement, and the historic election of the first African American president.2John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 227-38; Eoin Higgins, “The White Backlash to the Civil Rights Movement” (May 22, 2014), available at https://eoinhiggins.com/the-white-backlash-to-the-civil-rights-movement-1817ff0a9fc; David Elliot Cohen and Mark Greenberg, Obama: The Historic Front Pages (New York/London:Sterling, 2009); Adam Shatz, “How the Obama’s Presidency Provoked a White Backlash,” Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2016. Available at http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-shatz-kerry-james-marshall-obama-20161030-story.html

During some of America’s worst racial crises, the Bahá’í community has joined the gallant struggle not only to hold back the tide of racism but also to build a multiracial community based on the recognition of the organic unity of the human race. Inspired by this spiritual and moral principle, the Bahá’í community, though relatively small in number and resources, has, for well over a century, sought ways to contribute to the nation’s efforts to achieve racial justice and racial unity. This has been a work in progress, humbly shared with others. It is an ongoing endeavor, one the Bahá’í community recognizes as “a long and thorny path beset with pitfalls.”3Shoghi Effendi, The Advent of Divine Justice, Available at www.bahai.org/r/720204804

As the Bahá’í community learns how best to build and sustain a multiracial community committed to racial justice and racial unity, it aspires to contribute to the broader struggle in society and to learn from the insights being generated by thoughtful individuals and groups working for a more just and united society.

This article provides a historical perspective on the Bahá’í community’s contribution to racial unity in the United States between 1912 and 1996. The period of 1996 to the present—a “turning point” that the Universal House of Justice characterized as setting “the Bahá’í world on a new course”4Universal House of Justice, from a letter dated 10 April 2011 in Extracts from Letters Written on Behalf of the Universal House of Justice to Individual Believers in the United States on the Topic of Achieving Racial Unity (Updated Compilation 1996-2020), [7],5. Available at https://greenlakebahaischool.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/compilation-uhj-on-race-unity-1996-2020.pdf One aim of this extraordinary period from 1996 to the present has been to empower distinct populations and, indeed, the masses of humanity to take ownership of their own spiritual, intellectual, and social development. A future article will look at the impact of this latter period on the approach to the racial crisis in the United States. Recent articles on community building and approaches to building racial unity in smaller geographic spaces provide valuable insights about developments during this period. and increasing its capacity to contribute to social progress—is still underway. During the past twenty-five years, the Bahá’í community’s capacity to contribute to humanity’s efforts to overcome deep-rooted social and spiritual ills has advanced significantly, and a subsequent article will focus on the implications of this distinctive period on the community’s ability to foster racial justice and unity.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Visit: Laying the Foundation for Racial Unity, 1912-1921

The Bahá’í community’s first major contribution to racial unity began in 1912 when ‘Abdul’-Bahá, the son of the Founder of the Bahá’í Faith, Bahá’u’lláh (1817-1892), visited the United States. His historic visit occurred during one of the worst periods of racial terrorism in the United States against African Americans. According to historians John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, “In the first year of the new century more than 100 Negroes were lynched and before the outbreak of World War 1 the number for the century was 1,100.” 5Franklin and Moss, 282. In 1906, riots broke out in Atlanta, Georgia, where “whites began to attack every Negro they saw.”6Franklin and Moss, 283. That same year, race riots also occurred in Brownsville, Texas.7Franklin and Moss. Two years later, in 1908, there were race riots in Springfield, Illinois.8Franklin and Moss, 285. And in 1910, nation-wide race riots erupted in the wake of the heavyweight championship fight between Jack Johnson (Black) and Jim Jeffries (White) in Reno, Nevada, in July of that year.9Matt Reimann, “When a black fighter won ‘the fight of the century,’ race riots erupted across America.” May 25, 2017. Available at https://timeline.com/when-a-black-fighter-won-the-fight-of-the-century-race-riots-erupted-across-america-3730b8bf9c98

Racial turmoil prevailed before and after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit. Yet, in this raging period of racial terrorism and conflict, He proclaimed a spiritual message of racial unity and love, and infused this message into the heart and soul of the fledgling Bahá’í community—a community still struggling to discover its role in promoting racial amity. Before His visit to the United States, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent a message to the 1911 Universal Race Conference in London in which He compared humankind to a flower garden adorned with different colors and shapes that “enhance the loveliness of each other.”10G. Spiller, ed., Papers on Inter-Racial Problems Communicated to the First Universal Races Congress Held at the University of London, July 26-29, 1911. Rev. ed. (Citadel Press, 1970), 208.

The next year, in April, 1912, He gave a talk at Howard University, the premier African-American university in Washington D.C. A companion who kept diaries of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Western tours and lectures wrote that whenever ‘Abdu’l-Bahá witnessed racial diversity, He was compelled to call attention to it. For example, His companion reported that, during His talk at Howard University, “here, as elsewhere, when both white and colored people were present, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá seemed happiest.” Looking over the racially mixed audience, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had remarked: “Today I am most happy, for I see a gathering of the servants of God. I see white and black sitting together.”11‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/098175321

After two talks the next day, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was visibly tired as He prepared for the third talk. He was not planning to talk long; but, here again, when he saw Blacks and Whites in the audience, He became inspired. “A meeting such as this seems like a beautiful cluster of precious jewels—pearls, rubies, diamonds, sapphires. It is a source of joy and delight. Whatever is conducive to the unity of the world of mankind is most acceptable and praiseworthy.”12‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/322003373 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá then went on to elaborate on the theme of racial unity to an audience of Blacks and Whites who had rarely, if ever, heard such high praise for an interracial gathering. He said to those gathered that “in the world of humanity it is wise and seemly that all the individual members should manifest unity and affinity.”13‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/635635504

In the midst of a period saturated with toxic racist and anti-Black language, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá offered positive racial images woven into a new language of racial unity and fellowship. He painted a picture for his interracial audience: “As I stand here tonight and look upon this assembly, I am reminded curiously of a beautiful bouquet of violets gathered together in varying colors, dark and light.”14‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/947904389 To still another racially mixed audience, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá commented: “In the clustered jewels of the races may the blacks be as sapphires and rubies and the whites as diamonds and pearls. The composite beauty of humanity will be witness in their unity and blending.”15‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/635635504

Through His words and actions, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá demonstrated the Bahá’í teachings on racial unity. Several examples stand out. Two Bahá’ís, Ali-Kuli Khan, the Persian charge d’affaires, and Florence Breed Khan, his wife, arranged a luncheon in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s honor in Washington D.C. The guests were members of Washington’s social and political elite. Before the luncheon, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent for Louis Gregory, a lawyer and well-known African American Bahá’í. They chatted for a while, and when lunch was ready and the guests were seated, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá invited Gregory to join the luncheon. The assembled guests were no doubt surprised by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s inviting an African American to a White, upper-class social affair, but perhaps even more so by the affection and love ‘Abdu’l-Bahá showed for Gregory when He gave him the seat of honor on His right. A biographer of Louis Gregory pointed out the profound significance of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s action: “Gently but yet unmistakably, ‘Abdul-Bahá has assaulted the customs of a city that had been scandalized a decade earlier by President’s Roosevelt’s dinner invitation to Booker T. Washington.”16Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 53.

The promotion of interracial marriage was yet another example of how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá demonstrated the Bahá’í teachings on racial unity. Many states outlawed interracial marriage or did not recognize such unions; yet, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá never wavered in his insistence that Black and White Bahá’ís should not only be unified but should also intermarry. Before his visit to the United States, He had first broached the subject in Palestine with several Western Bahá’ís and explored the sexual myths and fears at the core of American racism. His solution was to encourage interracial marriage. Once in the U.S., He demonstrated the lengths to which the American Bahá’í community should go to show its dedication to racial unity when He encouraged the marriage of Louis Gregory and an English Bahá’í, Louisa Mathew. Their marriage was the first Black-White interracial marriage that was personally encouraged by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. This demonstration of Bahá’í teachings proved difficult for some Bahá’ís who doubted that such a union could last in a racially segregated society, but the marriage lasted until the end of the couple’s lives, nearly four decades later. Throughout this period, Louis and Louisa became a shining example of racial unity.17Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 63-72, 309-10.

Race Amity Activities: The Bahá’í Community’s Responses to Racial Crises, 1921-1937

Although working endlessly to promote racial unity through inspiring talks and actions, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá understood the persistent reality of racism in the U.S. In a letter to a Chicago Bahá’í, He predicted what would happen if racial attitudes did not change: “Enmity will be increased day by day and the final result will be hardship and may end in bloodshed.”18Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 59. Several years later, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá repeated this warning to an African American Bahá’í that “if not checked, ‘the antagonism between the Colored and the White, in America, will give rise to great calamities.’”19Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 59.

Tragically, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s predictions came true. Five years after His visit to the U.S. where He laid the foundation for the American Bahá’í community’s future contributions to racial unity, race riots broke out in 1917 in East St. Louis, Illinois, and other cities. Two years later, in 1919, “the greatest period of interracial strife the nation had ever witnessed”20John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 313. rocked the country. From June to the end of the year, there were approximately twenty-five race riots.21John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 313. With the country still in the throes of racial upheaval, ‘Abdul-Bahá, frail and worn, gathered the strength to rally the American Bahá’í community for what would become one of its signature contributions to racial amity in the U.S. In 1920, He mentioned the tragic state of race relations in the U.S. to a Persian Bahá’í residing in that country: “Now is the time for the Americans to take up this matter and unite both the white and colored races. Otherwise, hasten ye towards destruction! Hasten ye to devastation!”22Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 59.

That same year, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá initiated a plan to address the racial crisis in America. As Louis Gregory wrote in his report on the First Race Amity Convention held in Washington, D.C., May 19 to 21, 1921: “ It was following His return to the Holy Land…after the World War that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá set in motion a plan that was to bring the races together, attract the attention of the country, enlist the aid of famous and influential people and have a far-reaching effect upon the destiny of the nation itself.”23Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006),180. Originally published in The Bahá’í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol.7, 1936-1938, compiled by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá’í Publishing Committee). In His message to this first Race Amity Convention, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote: “Say to this convention that never since the beginning of time has one more important been held. This convention stands for the oneness of humanity; it will become the cause of the enlightenment of America. It will, if wisely managed and continued, check the deadly struggle between these races which otherwise will inevitably break out.”24Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006),180. Originally published in The Bahá’í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol.7, 1936-1938, compiled by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá’í Publishing Committee).

This first race amity convention could not have come at a better time. Ten days later, on May 31 and June 1, a race riot, also known as “the Tulsa race massacre,” occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “It has been characterized as ‘the single worst incident of racial violence in American history’” when “mobs of white residents, many of them deputized and given weapons by city officials, attacked black residents and businesses.” 25Wikipedia, “Tulsa Race Massacre”. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_massacre They not only attacked Blacks on the ground but also used private aircrafts to attack them from the air. The attacks resulted in the destruction of the Black business district known as Black Wall Street, “at the time the wealthiest black community in the United States.”26Wikipedia, “Tulsa Race Massacre”. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_massacre

One can only imagine what went through the minds of participants in the interracial gathering at that historic first race amity convention in Washington D.C. as the news of the Tulsa race riot swept the nation. Perhaps their minds raced back to a similar but less destructive race riot that had ravaged their own city during the “red summer”27John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 314 two years earlier. Some were probably thankful that they were part of a budding interracial movement dedicated to racial amity.

Louis Gregory reflected this optimism after the first race amity convention when he reported: “Under the leadership and through the sacrifices of the Bahá’ís of Washington three other amity conventions…were held….Christians, Jews, Bahá’ís, and people of various races mingled in joyous and serviceable array and the reality of religion shone forth.”28Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006),182. Originally published in The Bahá’í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol.7, 1936-1938, compiled by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá’í Publishing Committee). He related that “the Washington friends continued their race amity work in another form by organizing an interracial discussion group which continued for many years and did a very distinctive service, both by its activities and its fame as the incarnation as a bright ray of hope amid scenes where racial antagonism was traditionally rife.”29Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006),182. Originally published in The Bahá’í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol.7, 1936-1938, compiled by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá’í Publishing Committee).

From the year of the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in 1921 to 1937, the Bahá’í-inspired race amity movement— a lighthouse of racial hope—cast a sometimes small but powerful beam of light through a thick fog of racism. Notwithstanding setbacks, it made a mighty effort to steady that beam of light. In city after city across the country, brave and courageous peoples of all races and religions joined the movement. In December of 1921, Springfield, Massachusetts, followed Washington D.C. Three years later, New York joined the ranks of race amity workers. That same year Philadelphia—”the City of Brotherly Love” — held its first Race Amity Convention and followed it up six years later (1930) with another one. 30Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006),182-185. Originally published in The Bahá’í World: A Biennial International Record, Vol.7, 1936-1938, compiled by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada (New York: Bahá’í Publishing Committee).

In 1927, a year Louis Gregory called “that memorable year for amity conferences,”31Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 185 a race amity conference was held in Dayton, Ohio. The Dayton community hosted a second race amity conference in 1929.32Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 186. According to Gregory, “Race amity conferences at Green Acre, the summer colony of the Bahá’ís in Maine, cover[ed] the decade beginning in 1927,”33Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (34. Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 186 a decade which he referred to as “this fruitful period,”34Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 187 when Geneva, New York, Rochester, New York, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Boston all contributed their share to the race amity movement.35Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 192-93 “The friends in Detroit, under the rallying cry, ‘New Views on an Old, Unsolved Human Problem,’ raised the standard of unity in a conference March 14, 1929.”36Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 193 In Atlantic, City, with only one “active Bahá’í worker in the field,” not even the opposition of “the orthodox among the clergy…which unfavorably affected the press”37Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 193-94 could stem the tide of the race amity movement. On April 19, 1931, assisted by the Bahá’ís of Philadelphia, The Society of Friends, and other organizations, close to four hundred people attended a gathering.38Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 194 Five months later, in October, the Pittsburgh Bahá’ís arranged a conference.39Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 195

Bahá’ís and their friends and associates in Denver, Portland, Seattle, and Los Angeles all joined hands as they expanded the circle of unity beyond Black and White to include Native Americans, Chinese-Americans, and Japanese-Americans.40Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 195-96. The Bahá’ís also held interracial dinners and banquets. Such banquets “appeared to give to those who shared them a foretaste of Heaven,” 41Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 196. Gregory wrote. One of the last race amity conferences was held in Cincinnati, Ohio, in April of 1935, and was considered

one of the most interesting and influential of all. The Bahá’ís…having with one mind and heart decided upon such an undertaking, under the guidance of their Spiritual Assembly—the local Bahá’í governing council—proceeded to work the matter out in the most methodical and scientific way. [In addition] they succeeded in laying under the tribute of service some sixteen others noted for welfare and progress.42Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 197.

The Bahá’í racial amity activities also included three interracial journeys of Black and White Bahá’ís “into the heart of the South.” They were inspired by the wishes of Shoghi Effendi, who became of the Head of the Bahá’í Faith after the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and was designated the title “Guardian.”43Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 198. Interracial teams of two Bahá’í men, Black and White, traveled South in the autumn of 1931, the spring of 1932, and the winter of 1933. “One of the most interesting discoveries of [the 1931 team’s] trip was to find the same interest at the University of South Carolina, for Whites, as at Allan University and Benedict College, located in the same City of Columbia, for Colored.”44Louis Gregory, “Racial Amity in America: An Historical Review,” in Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis & Richard Thomas, eds, Lights of the Spirit: Historical Portraits of Black Bahá’ís in North American: 1898-2000 (Wilmette, Ill.: Baháί Publishing, 2006), 199.

The Most Challenging Issue: Preparing the American Bahá’í Community to Become a Model of Racial Unity

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the American Bahá’í community contributed its share to promoting racial unity and to lessening, to some degree, the relentless forces of racism. They brought people together in conferences to discuss delicate racial issues and created intimate spaces, such as banquets and interracial dinners in which to break bread, at a time when sitting down and eating together was the prevailing social taboo. These were no small accomplishments. These experiences seeded future interracial meetings and friendships. More work had to be done, however, before the Bahá’í community could move to the next stage of its contribution to racial unity in the larger society. It had to prepare itself to become, at the very least, a work in progress of a model of racial unity.

Foremost among the Guardian’s concerns for the United States was racial prejudice and its influence on the American Bahá’í community. In his lengthy letter to the American Bahá’í community, which was published as The Advent of Divine Justice (1939), he characterized racism as “the corrosion of which, for well-nigh a century has bitten into the fiber, and attacked the whole social structure of American society” and said it should be “regarded as constituting the most vital and challenging issue confronting the Bahá’í community at the present stage of its evolution.” He told Bahá’ís of both races that they faced “a long and thorny road beset with pitfalls” that “still remained untraveled.”45Shoghi Effendi, Advent of Divine Justice. Available at www.bahai.org/r/720204804 Both races were assigned specific responsibilities. White Bahá’ís were to

make a supreme effort in their resolve to contribute their share to the solution of this problem, to abandon once for all their usually inherent and at times subconscious sense of superiority, to correct their tendency towards revealing a patronizing attitude towards the members of the other race, to persuade them through their intimate, spontaneous and informal association with them of the genuineness of their friendship and the sincerity of their intentions, and to master their impatience of any lack of responsiveness on a part of a people who have received, for so long a period, such grievous and slow-healing wounds.46Shoghi Effendi, Advent of Divine Justice. Available at www.bahai.org/r/376777192

Black Bahá’ís were to “show by every means in their power the warmth of their response, their readiness to forget the past, and their ability to wipe out every trace of suspicion that may still linger in their hearts and minds.”47Shoghi Effendi, Advent of Divine Justice. Available at bahai.org/r/376777192 Neither race could place the burden of resolving the racial problem within the Bahá’í community on the other race or to see it as “a matter that exclusively concerns the other.”48Shoghi Effendi, Advent of Divine Justice. Available at bahai.org/r/376777192

As well, the Guardian cautioned Bahá’ís that they should not think the problem could be easily or immediately resolved. They should not “wait confidently for the solution of this problem until the initiative has been taken, and the favorable circumstances created, by agencies that stand outside the orbit of their Faith.”49Shoghi Effendi, Advent of Divine Justice. Available at bahai.org/r/376777192 Rather, Shoghi Effendi encouraged Bahá’ís to