The quarter century between 1996 and 2021 was a period of mounting racial contention in the United States. Marked by increased police killings of unarmed African Americans, race riots, burning of Black churches in the Deep South, the rise and spread of white supremacy movements, and wide-spread racial polarization, it resembled some of the worst racial strife of the 1960s. Not even the historic election of the first Black president, which many hoped would usher in a post-racial society, could turn the tide.1Cheryl W. Thompson, “Final police shooting of unarmed black people reveals troubling patterns,” Morning Edition, National Public Radio, 25 January 2021. http://www.npr.org/202101/25/95617701/fatal-police-shooting-of-unarmed-black-people-reveal-troubling-pattern. “Unrest in Virginia: Clashes over a show of white nationalism in Charlottesville turn deadly,” Time, https://time.com/charlottesville-whitenationalism-rally-clashes. https://sites.goggle/a/mmicd.org/american-racie-and-racism-1970-to-present/home/1990s. “Read the full transcript of President Obama’s farewell speech,” Los Angeles Times, 10 January 2017. https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-pol-obama-farewell-speech-transcript-20170110-story.html.

During that period, the American Bahá’í community’s longstanding dedication to racial harmony and justice continued to be expressed in numerous initiatives undertaken by individuals and organizations. These initiatives unfolded amidst a period of profound advancement across the Bahá’í world. In 1996, the worldwide Bahá’í community entered a new stage in its development, propelled by a series of global Plans that successively guided “individuals, institutions and communities” to build the capacity to “[translate] Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings into action.”2Universal House of Justice. Riḍván 2021 message. Available at www.bahai.org/r/750707520 In turn, this progress made the possibilities for social transformation more and more visible to those laboring in the field of service and had implications for the efforts of Bahá’ís to combat racial prejudice and injustice.

In July 2020, for the first time in more than 30 years, the House of Justice addressed the American Bahá’í community, as it had done during other periods of racial turmoil in the United States:

A moment of historic portent has arrived for your nation as the conscience of its citizenry has stirred, creating possibilities for marked social change. … you are seizing opportunities—whether those thrust upon you by current circumstances or those derived from your systematic labors in the wider society—to play your part, however humble, in the effort to remedy the ills of your nation. We ardently pray that the American people will grasp the possibilities of this moment to create a consequential reform of the social order that will free it from the pernicious effects of racial prejudice and will hasten the attainment of a just, diverse, and united society that can increasingly manifest the oneness of the human family.”3Universal House of Justice. Letter to the Baha’is of the United States dated 22 July 2020. Available at www.bahai.org/r/870410250

In the letter, the House of Justice pointed out the difficult path ahead amidst inevitable setbacks, saying: “Sadly, however, your nation’s history reveals that any significant progress toward racial equality has invariably been met by countervailing processes, overt or covert, that served to undermine the advances achieved and to reconstitute the forces of oppression by other means.” The “concepts and approaches for social transformation developed in the current series of Plans,” explained the House of Justice, could be “utilized to promote race unity in the context of community building, social action, and involvement in the discourses of society.”4Universal House of Justice, United States, 22 July 2020. Available at at https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/20200722_001/1#870410250

The sections below review developments in the US Bahá’í community during the period between 1996 and 2021, exploring their implications for the community’s response to racial injustice and the pursuit of racial unity.

1996 – 2006: Building Capacity Through Focus on a Single Aim

For the Bahá’í world, the Four Year Plan (1996 – 2000), the first in the series of global Plans spanning the quarter century, marked a “turning point of epochal magnitude.”5Universal House of Justice, Riḍván 153. Available at www.bahai.org/r/328665132 The Plan assisted the Bahá’í community to mature in its understanding of transformation—both internally and in the world at large.

First clumsily and then with increasing ability, more and more Bahá’ís from diverse national communities learned to take action within a common framework. While it took more than a decade for new patterns of thought and action to take root across the US, the systematic approach called for by the House of Justice came to be appreciated as a vital facet of the American community’s efforts to combat deeply entrenched social ills, especially racism.

In parallel to the processes unfolding in the Bahá’í world, the 1990s and early 2000s saw Bahá’ís in the US continue to participate in a range of race-related activities in the wider society, often taking part in, and sometimes leading, initiatives in support of racial harmony. For example, many local Bahá’í communities participated in annual celebrations in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a leader of the nonviolent civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In June 1965, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States sent a telegram to Dr. King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, supporting the historic march on Montgomery: “YOUR MORAL LEADERSHIP HUMAN RIGHTS IN SOUTH PRAISEWORTHY HISTORY MAKING FREEDOM IN UNITED STATES. SENDING REPRESENTATION MONTGOMERY AFFIRM YOUR CRY FOR UNITY OF AMERICANS AND ALL MANKIND.”6Baha’i News (June 1965): 13. This relationship between the annual Martin Luther King Day celebrations and the Bahá’í race unity work has continued through the years. In 2002, the Bahá’í community of Houston was asked to lead and close their local parade, which attracted some 300,000 people to the parade route and was partially broadcast on four national television networks.7“Year in Review,” The Baha’i World, 2001 – 2002 (Haifa, Israel: Baha’i World Centre, 2003), 84. Similarly, a number of Bahá’í communities participated in interfaith services responding to the burning of Black and multiracial churches.8“Year in Review,” 2001 – 2002, 76.

At the same time, Bahá’ís were initiating their own efforts to promote racial harmony and justice in light of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings. The Local Spiritual Assembly of Detroit, Michigan appointed a task force with a mandate to promote racial unity, which for seven years (ending in 2000) promoted and conducted an annual Models of Racial Unity Conference involving Bahá’í and non-Bahá’í speakers from a range of diverse professional, racial, ethnic and religious community groups and associations.9Joe T. Darden and Richard W. Thomas, Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts, and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013), 282-289.

In 1998, the US National Spiritual Assembly launched a national campaign to raise awareness of issues related to race unity in the country. The campaign included a television program called The Power of Race Unity, which aired on several national broadcast stations, as well as many local and regional channels, and a document penned by the National Assembly entitled Race Unity: The Most Challenging Issues, which was mailed to several thousand homes. It was estimated that 80 percent of local Bahá’í communities in the country hosted activities in support of the campaign, ranging from private viewings of the video to workshops and public discussions about racial unity.10Year In Review,” The Baha’i World, 1998 – 1999 (Haifa, Israel: Baha’i World Centre, 2000), 91-92.

The opening of the Louis G. Gregory Bahá’í Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, on 8 February 2003,11Nancy Branham Songer, “A Beacon of Unity: The Louis G. Gregory Baha’i Museum, Charleston, South Carolina,” World Order, 36, No. 1 (2004), 45. was among the most special developments of the period. The museum honored a dedicated champion who personified the American Bahá’í community’s long and unyielding commitment to racial unity and justice. According to one source, this was the “first Bahá’í museum in the world.” It honored “both a descendant of a black slave and a white plantation owner” in a city “through whose port an untold number of Africans passed into slavery and whose citizens witnessed the shots that came to symbolize the beginning of the Civil War.”12Songer, “A Beacon of Unity,” 45. It was hailed by one speaker at the dedication as a “beacon of unity” for the world.13Songer, “A Beacon of Unity,” 45.

Additionally, this decade saw ongoing efforts to tend to the hearts of, and build capacity among, African Americans within the Bahá’í community, especially African-American men, long subject to injustice in the form of harmful stereotypes, police brutality, staggering community violence, and mass incarceration. Many of these Bahá’ís did not find within the dynamics of their Bahá’í communities the patterns of worship, praise, and mutual support for which they longed. In many cases, their participation faded until they were invited back by the warmth of a series of gatherings known as the Black Men’s Gathering.14Frederick Landry, Harvey McMurray, and Richard W. Thomas, The Story of the Baha’i Black Men’s Gathering: Celebrating Twenty-Five Years, 1987 – 2011 (Wilmette, Illinois: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 2011).

Between 1987 and 2011, the Black Men’s Gathering was dedicated to “soothing hearts” of black Bahá’í men who “had sustained slow-healing wounds” and “cultivating capacity for participation in a world-embracing mission.”15Universal House of Justice. Letter to the participants of the Black Men’s Gathering dated 28 August 2011. From the growing numbers of African-American men involved in the process arose melodies of praise and worship resonant with the African-American tradition, and gatherings led to travels to share the message of the Faith throughout many countries in Africa and the Caribbean. In July 1996, for example, more than one hundred Black Bahá’í men from the US, the Caribbean, Canada, and Africa attended the Tenth Annual Black Men’s Gathering in Hemingway, South Carolina, at the Louis Gregory Institute. In response to the call of the Universal House of Justice to “be a unique source of encouragement and inspiration to their African brothers and sisters who are now poised on the threshold of great advances for the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh,”16Universal House of Justice. Riḍván 153 message to the Followers of Bahá’u’lláh in North America: Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. Available at www.bahai.org/r/064654502. forty-five of the participants “pledged to visit Africa over the following three years to share Bahá’u’lláh’s message with the people there.17“Year in Review,” The Baha’i World, 1996 – 1997 (Haifa, Israel: Baha’i World Centre, 1998), 58.

In 2004, the editors of a national Bahá’í publication, World Order magazine, published a special issue with the following introduction: “We found that the fiftieth anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 decision of the United State Supreme Court that started the judicial desegregation of U.S. schools, afforded an opportunity to look at the matter from a number of perspectives.” The issue included articles examining the historic decision from the contexts of law, the teaching of history, and psychology, among others, written by Bahá’ís from diverse professional fields, racial and cultural backgrounds, and experience in promoting racial unity.”18 “Year in Review,” 1996 – 1997, 58.

These highly meritorious efforts carried forward the American Bahá’í community’s legacy of dedicated service to the cause of race unity, yet the community had a considerable distance to go in making the shift called for by the House of Justice to an approach focused on systematic processes that would build capacity in individuals and groups, and eventually in whole populations, to contribute to the kind of transformation that could ultimately dismantle the disease of racism.

In the country’s history, every time racism appeared to have been dealt a major blow—with the end of slavery, or the end of legal segregation, for example—it managed to rear up in a new form. It has proven itself deeply entrenched in American society. For this reason, notwithstanding the many activities that Bahá’ís had undertaken to address racial concerns, and their obvious merits and achievements, the ultimate results of such efforts had often been limited in their effect. As the Universal House of Justice noted, such efforts have often been characterized by “a cyclical pattern, with fits and starts,” presented with fanfare while failing to elicit universal participation.19Universal House of Justice. “Achieving Race Unity and Advancing the Process of Entry by Troops” (extracts from letters to individual believers in the United States), dated 10 April 2011. Activities, often accompanied by great enthusiasm and energy, would reach a peak and then, after a period of time, lose momentum and atrophy. For this reason, developing the capacity for collective, systematic action needed to receive a greater share of the attention of the American community. The groundwork for such an advance was more firmly laid in the next decade.

2006 – 2016: Unlocking the “Society-Building Powers of the Faith”

During the second decade, through two consecutive Five Year Plans, the Universal House of Justice guided the worldwide Bahá’í community to explore how Bahá’í teachings can be applied at the grassroots to give rise to a new kind of community. As the House of Justice itself described in 2013:

Bahá’ís across the globe, in the most unassuming settings, are striving to establish a pattern of activity and the corresponding administrative structures that embody the principle of the oneness of humankind and the convictions underpinning it, only a few of which are mentioned here as a means of illustration: that the rational soul has no gender, race, ethnicity or class, a fact that renders intolerable all forms of prejudice … that the root cause of prejudice is ignorance, which can be erased through educational processes that make knowledge accessible to the entire human race, ensuring it does not become the property of a privileged few. Translating ideals such as these into reality, effecting a transformation at the level of the individual and laying the foundations of suitable social structures, is no small task, to be sure. Yet the Bahá’í community is dedicated to the long-term process of learning that this task entails, an enterprise in which increasing numbers from all walks of life, from every human group, are invited to take part.20Universal House of Justice. Message to the Baha ’is of Iran dated 2 March 2013. Available at www.bahai.org/r/063389421

Much of the development witnessed during these years had long-term implications for the American Bahá’í community’s approach to racial justice and unity. This section will focus on two developments in particular. First, significant progress was made in learning to channel the energies of youth toward social progress. Second, the Bahá’í community, for which the betterment of society is a primary aim, evolved in its approach to, and understanding of, social transformation. As experience accumulated, the community also came to understand better the relationship between its own growth and development and its participation in the life of society at large.

Youth at the Vanguard

Regarding the first development, in December 2005, the House of Justice drew attention to the latent potential of young people ages 12 to 15, referring to them as “junior youth” and noting that they “represent a vast reservoir of energy and talent that can be devoted to the advancement of spiritual and material civilization.”21Universal House of Justice. Message to the Conference of the Continental Boards of Counsellors dated 27 December 2005. Available at www.bahai.org/r/527522699. The junior youth spiritual empowerment program began to take off in diverse settings around the world and showed great promise in preparing adolescents to contribute to social change. At an age when intellectual, spiritual, and physical powers rapidly develop, junior youth in the program were assisted to explore the social conditions around them, to analyze the constructive and destructive forces operating in their lives, and to develop the tools needed to combat negative social forces such as materialism, prejudice, and self-centeredness.22Universal House of Justice. Riḍván 2010 message. Available at www.bahai.org/r/178319844

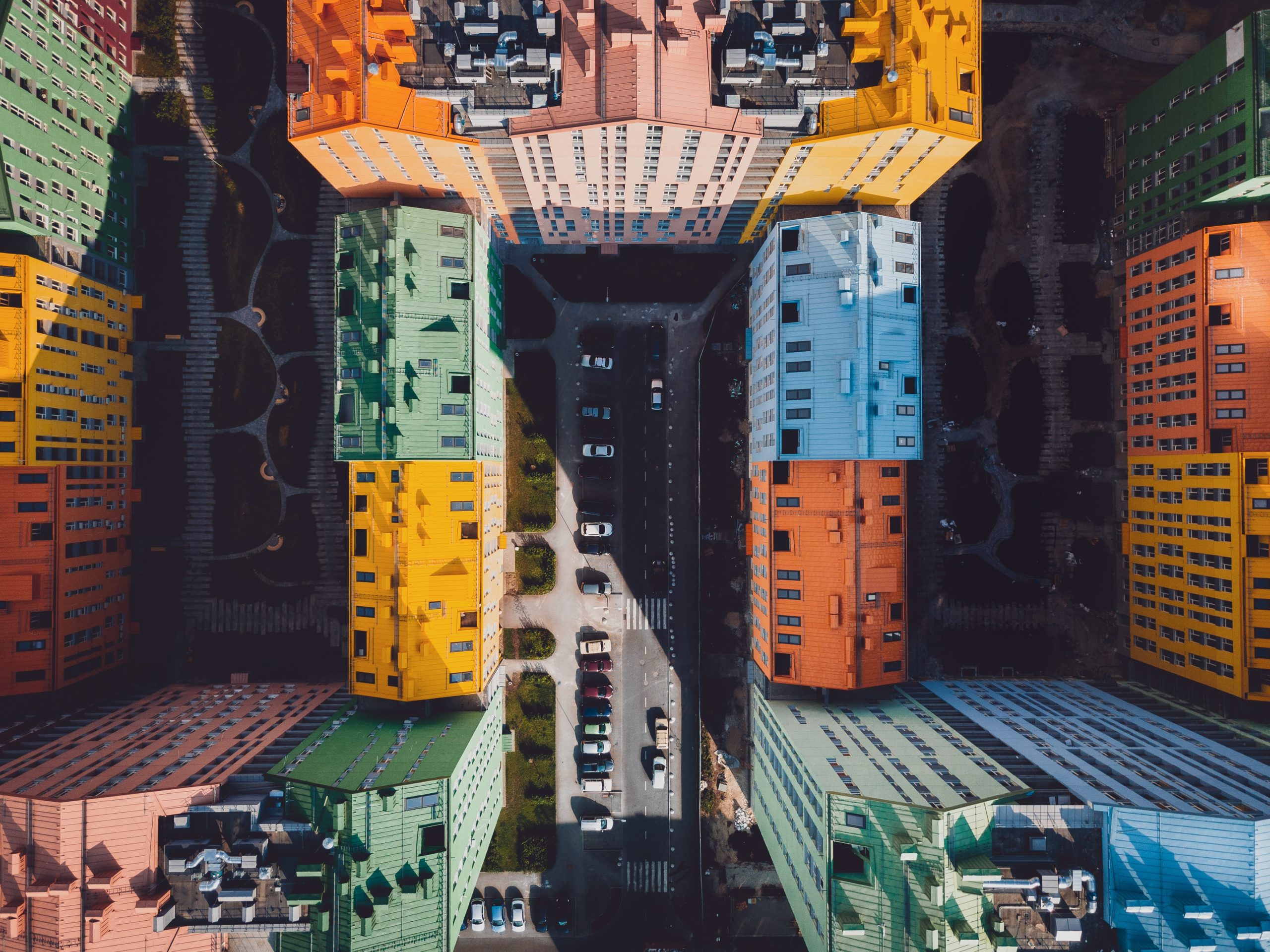

In the US, the junior youth spiritual empowerment program was established in neighborhoods representing a range of racial and ethnic diversity—some on indigenous lands, some in primarily Latino areas, others in predominantly African-American locations, and some in the most diverse neighborhoods in the country, comprising immigrants from all parts of the world. Through the program, young people in each of these contexts developed the capabilities necessary to contribute to the betterment of their communities. In an unjust social system that has tended to exclude racial and ethnic minorities from the American promises of equity and economic opportunity, in which forces of materialism distract those not benefitting from the system with harmful vices and mindless consumerism, the junior youth program, little by little, planted the seeds of possibility for change.

Central to the program is an educational curriculum that enhances participants’ intellectual capacities, helps build moral structure, and cultivates spiritual qualities and perception. The texts of the program seek to address the root causes of prejudice. For example, the text Glimmerings of Hope presents the story of a junior youth whose parents are killed in civil strife between two different ethnic groups. In the stories that follow, he learns that, even in the face of very painful and difficult circumstances, people have choices to make; they can opt for hope and love or let themselves fall prey to forces of hatred and division. In Observation and Insight, as a young girl learns to observe her physical environment and the social conditions of her village, she comes to question the prejudice in her community and is helped to think about ways to combat prejudice, both within herself and in the world around her.

As the junior youth program began to advance in the US, it also highlighted the distinctive role that youth play, not only in nurturing those younger than them, but in all facets of community life. The spiritual empowerment of the population between ages 15 and 30 became a central focus of this period. As more and more youth engaged in the sequence of courses offered by training institutes, they were assisted to apply what they learned in the context of community transformation. Foundational to the efforts was the concept of a “twofold moral purpose,” that is, “to attend to one’s own spiritual and intellectual growth and to contribute to the transformation of society.”23Reflections on the Life of the Spirit (Ruhi Institute, 2020), v. In 2013, the Universal House of Justice called for a series of worldwide youth conferences. In the US, approximately 5,800 young people of varied backgrounds, including roughly 2,000 youth of indigenous, Asian, African-American, and Latino heritages, attended.24“114 youth conferences, July – October 2013,” Baha’i Community News Service. https://News.bahai.org/community-new/youth-conferences. 25“2013 Youth Conference Statistics.” Internal report dated 8 August 2013.

Contributing to Social Transformation

Regarding the second process, the work unfolding at the grassroots in numerous societies naturally drew members of the Bahá’í community into closer contact with diverse populations—comprising individuals, families, and organizations with whom they worked side by side—on city blocks in major urban centers and in neighborhoods, villages, and towns.

A new pattern emerged. Whereas many Bahá’ís were accustomed to bringing people one by one into their existing faith community—which has its own culture, habits, and ways of doing things—Bahá’í communities were now learning to take the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh to whole populations, creating the possibility for such populations to investigate the Bahá’í teachings and apply them for the progress of their own people. To approach the masses of humanity in such a manner required a substantial shift in orientation for many in the Bahá’í community.

The Universal House of Justice on numerous occasions helped the Bahá’í world expand its vision and clarify its sense of mission, cautioning the community not to close in on itself or to separate itself from the world at large:

A small community, whose members are united by their shared beliefs, characterized by their high ideals, proficient in managing their affairs and tending to their needs, and perhaps engaged in several humanitarian projects—a community such as this, prospering but at a comfortable distance from the reality experienced by the masses of humanity, can never hope to serve as a pattern for restructuring the whole of society. That the worldwide Bahá’í community has managed to avert the dangers of complacency is a source of abiding joy to us. Indeed, the community has well in hand its expansion and consolidation. Yet, to administer the affairs of teeming numbers in villages and cities around the globe—to raise aloft the standard of Bahá’u’lláh’s World Order for all to see—is still a distant goal.26Universal House of Justice. Message to the Conference of the Continental Boards of Counsellors. 28 December 2010. Available at www.bahai.org/r/525496636

During this period, American Bahá’ís established the basic elements of Bahá’í community-building activities in an increasing number of localities across the country. Those communities experienced, to varying degrees, the multiplication of devotional meetings open to all inhabitants, spiritual education classes for children, groups seeking to empower adolescents and older youth, and courses designed to develop the capacity of individuals to become active contributors to the betterment of the world around them. Critically, Bahá’ís learned to open these activities to the wider society. As they did so, some Bahá’ís whose backgrounds had afforded them relative freedom from exposure to prevalent injustices became cognizant of the reality faced by many of their fellows, with whom they were working for meaningful change.

Efforts in a predominantly African-American community, for instance, led to a tight fellowship between a growing number of residents and two Iranian-American Bahá’ís who had moved into the neighborhood. Members of the community came together weekly to pray and speak with one another about their lives, their struggles, and their aspirations for their children and grandchildren. A growing number of residents also studied courses of the training institute and offered classes for the spiritual education of children. Out of the rhythm of action and reflection that characterized these activities, there also emerged efforts to address local needs, with residents themselves taking the lead. The person responsible for cooking for children’s classes, for example, had faced challenges finding dignified employment. As he engaged in the progress of the community, he was inspired to prepare homecooked meals as a small business—an enterprise that was greatly valued in a locality with no grocery store nearby. Similarly, conversations in the community led to the formation of an organization dedicated to providing affordable eyeglasses to neighbors; at the writing of this article, more than 90 pairs of glasses had been distributed through this effort.27“Lessons Learned from Expansion within a Narrow Compass”. Internal report prepared by an Auxiliary Board member. The united and spiritually uplifted community forged through such activities offered a stark contrast to negative portrayals of the neighborhood in the media. Though nascent, this and many other examples demonstrate the deep wells of capacity, creativity, and desire for progress that exist in the masses of the country, the potentialities of which can be released when individuals and populations become spiritually empowered.

With such promising efforts underway, the Universal House of Justice helped members of the US Bahá’í community see the implications of what was being learned through efforts to combat the effects of racism. A letter written on its behalf to an individual believer in 2011 explained:

Only if the efforts to eradicate the bane of prejudice are coherent with the full range of the community’s affairs, only if they arise naturally within the systematic pattern of expansion, community building, and involvement with society, will the American believers expand their capacity, year after year and decade after decade, to make their mark on their community and society and contribute to the high aim set for the Bahá’ís by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to eliminate racial prejudice from the face of the earth.28Universal House of Justice. Letter to an individual believer dated 10 April 2011.

That same year, as those organizing the Black Men’s Gathering considered next steps, the Universal House of Justice offered encouragement to extend their efforts to many others in their local communities, drawing upon what was being learned in expansion and consolidation. A letter on its behalf explained that “the time has now come for the friends who have benefited from the Gathering to raise their sights to new horizons” and encouraged participants to “Let the well-prepared army you have assembled advance from its secure fortress to conquer the hearts of your fellow citizens,” for what was needed was “concerted, persistent, sacrificial action, cycle after cycle, in cluster after cluster, by an ever-swelling number of consecrated individuals.”29Universal House of Justice. Letter to the participants of the Black Men’s Gathering dated 28 August 2011. The same ethos of loving support, the spiritual devotion, and the dedication to service that had characterized the activities of the Black Men’s Gathering for over two decades could be extended locally to bring more people into the circle of unity drawn by Bahá’u’lláh—including neighbors, co-workers, families, and friends. Toward this lofty objective, participants of the Gathering could find in the methods and approaches of the Plan being strengthened during this period the tools necessary to address the challenges of racism in the country. As was explained in the same letter:

The experience of the last five years and the recent guidance of the House of Justice should make it evident that in the instruments of the Plan you now have within your grasp everything that is necessary to raise up a new people and eliminate racial prejudice as a force within your society, though the path ahead remains long and arduous. The institute process is the primary vehicle by which you can transform and empower your people, indeed all the peoples of your nation.30Universal House of Justice, Black Men’s Gathering, 28 August 2011.

In 1938, in Advent of Divine Justice, Shoghi Effendi noted that the US Bahá’í community was too small in number and too limited in influence to produce “any marked effect on the great masses of their countrymen,” but that as the believers intensified efforts to remove their own deficiencies, they would be better equipped for “the time when they will be called upon to eradicate in their turn such evil tendencies from the lives and hearts of the entire body of their fellow-citizens.”31Shoghi Effendi, The Advent of Divine Justice. Available at www.bahai.org/r/034096683 During the ten-year period between 2006 and 2016, the number of people, particularly young people, drawing insight from the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh with the aim of effecting the transformation of society grew, as did their capacity to begin contributing to profound social change. The national Bahá’í community had laid the groundwork for new possibilities to address racial injustice and pursue racial harmony—possibilities that began to manifest in the final five years of this twenty-five-year period.

2016 – 2021: Envisioning the Movement of Populations

The beginning of the most recent Five-Year Plan (2016 – 2021) coincided with an upsurge in racial turmoil in the US. Heart-wrenching incidents of racism continued to make national news during these years, including the fatal shootings of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed 17-year-old African-American boy in Florida, by a Hispanic-American private citizen in 2012, and of Michael Brown, an unarmed young African-American man with his hands in the air, by police in Missouri in 2014.32https://www.cnn.com/2012/05/18/justice/florida-teen-shooting-details/index.html. “The Killing of an Unarmed Teen: What we need to know about Brown’s Death.” NBC News. Available at https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/michael-brown-shooting-unarmed-teen-what-we-know-about-brown’s-death. On 17 June 2015, the country was shocked by the horrific mass shooting of nine African Americans in Charlestown, South Carolina, during Bible study at one of the oldest African-American churches in the South, by a 21-year-old self-identified white supremacist.33“This Day in History: Charleston Church Shooting.” 17 June 2015. https://www.history.history.com/this-day-inhistorycharleston-ame-church-shooting.

As the country geared up for a new presidential election in 2016, voices of racism on the national stage became more overt. In his farewell speech in January 2017, President Obama acknowledged the harsh reality of racism that still plagued the country. “After my election, there was talk of a post-racial America. Such a vision, however well-intended, was never realistic. For race remains a potent and often divisive force in our society.”34“Obama’s farewell speech,” Los Angeles Times, 10 January 2017. That same year, groups of white supremacists and neo-Nazis held a Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where they fought with anti-racism counter-protesters. Dozens were injured and one person was killed when a man drove into the anti-racism protesters.35“Unrest in Virginia,” Time.

Racially motivated acts of terror continued alongside entrenched social and economic injustice. In 2020, the Washington Post reported, “The black-white economic divide is as wide as it was in 1968.” And in January 2021, a National Public Radio investigation found that, since 2015, police officers had fatally shot at least 135 unarmed black men and women nationwide; in at least three-quarters of these shootings, the officers were white.36Thompson, “Final police shooting,” 25 January 2021.

Meanwhile, in those settings where developments had gone the furthest, the American Bahá’í community could see new models of community life emerging and glimpses of transformation at the grassroots. These lessons offered hope for genuine advancement in the community’s pursuit of race unity at the local and national levels.

Most notable, of course, were advances at the grassroots, where, in certain neighborhoods and city blocks, substantial numbers of local inhabitants became engaged in Bahá’í activities. Youth, in particular, took their place at the forefront of service, engendering hope and energy in their communities. Though nascent and modest in their scope, such experiences multiplied across the country, representing the first stirrings of the spiritual empowerment of populations.37Universal House of Justice. Message. 29 December 2015. Available at https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/20151229_001/1#275100978

A neighborhood surrounding a historically Black university in the Carolinas became home to exactly such a movement. In the US, it was legal to deny access to higher education solely on the basis of skin color as recently as the 1950s. Colleges and universities like this one, founded within that context to serve African-American populations, hold special significance. In 2016, what started as a small group of friends comprising Bahá’ís and their neighbors extended in five short years to embrace scores of youth, junior youth, and families. Cohorts of African-American university students, some the first in their families to attend college, spearheaded the emergence of dynamic community life that addressed both the spiritual and intellectual needs of children, youth, and adults. African-American and Latino junior youth groups formed and were increasingly empowered to undertake service projects that sought to address the needs of their community. Noticing that many children were assessed as having low levels of literacy, for example, the junior youth created a small lending library, wrote their own simple stories for the children, and set a regular time each week to read to them. At the same time, their families became active participants in community life. The parents of the junior youth in the program, for instance, brought neighbors together in community gatherings in which they could share a meal and discuss what they would like to see on their block. Devotional gatherings multiplied, and neighbors gathered together to pray, reflect, and share experiences, questions, and concerns. As participation grew and activities multiplied, social action initiatives emerged. Among them was a vaccination clinic.38“Lessons from the Grassroots: Fostering Nuclei of Transformative Change.” Panel at the National Symposium on Racial Justice and Social Change, hosted by the US Bahá’í Office of Public Affairs. 18 – 20 May 2021. The dynamic being experienced generated not only hope but also the first stirrings of the release of the potential of a population. Similar patterns were emerging, to varying degrees, in region after region in the United States.

While experience at the grassroots took root in a growing number of communities, the US National Spiritual Assembly initiated various actions to galvanize the entire national community to play its part in the advancement of racial justice and unity. These lines of action were, in part, laid out in a series of letters to the US Bahá’í community, calling attention to the “pivotal juncture in our nation’s history” during which Bahá’ís would be called to intensify their efforts to eliminate prejudice and injustice from society. The National Assembly drew the attention of the American Bahá’ís to their “twofold mission,” which is “to develop within our own community a pattern of life that increasingly reflects the spirit of the Baha’i teachings” and “to engage with others in a deliberate and collaborative effort to eradicate the ills afflicting our nation.” In pursuing this mission, the Bahá’ís had inherited “a priceless legacy of service spanning more than a century, originally set in motion by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Himself,” as well as “the framework of action given to us in the current Five Year Plan.” The more that the latter is understood, the Assembly asserted, “the better we can appreciate that it is precisely suited to the needs of the times.”39National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United States. Letter to the American Bahá’í community dated 25 February 2017. Bahá’ís were directed to deepen their “understanding of the forces at work in our society and the nature of our response as Bahá’ís—especially as outlined in the current set of Plans.” In their search “for answers and for a way forward,” the American people “are daily treated to a cacophony of competing voices” resting on “faulty foundations” and are longing for some “credible source” to which they can turn “for insight and hope.”40National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United States. Letter to the American Bahá’í community dated 31 January 2018. In response, the Bahá’í community was guided to engage with “specific populations mentioned numerous times by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and the Universal House of Justice for the unique and vital contribution they will make to the creation of the new social order envisaged” in the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh.41National Spiritual Assembly to American Bahá’í community, 31 January 2018.

The National Spiritual Assembly also pursued ways, within the offices of its National Center, to give further attention to questions of racial justice and race unity in the context of already occurring work. Permanent and seasonal schools made race relations one of their central issues of study and discussion for several years. The Assembly’s Social Action Desk—which focuses on the emergence of social action in communities across the country—directed its attention to efforts at the grassroots that were addressing aspects of racial injustice. Furthermore, a national media project collected and told stories of community life characterized by building across racial and cultural divides through the pursuit of the aims of the Five Year Plan.42https://www.bahai.us/collection/a-rich-tapestry/

In the nation’s capital, the US Bahá’í Office of Public Affairs allocated an increasing number of staff to participation in the national discourse on race through attendance at numerous conferences, workshops, and roundtables. Bahá’í representatives met with leading thinkers and organizations working to eradicate racism. In its contributions to the complex and polarizing discourse, the Office sought ways to offer novel perspectives based on the Bahá’í teachings, seeking insights into questions relating, for example, to the perceived tension between the pursuit of unity and the pursuit of justice and to the relationship between means and ends as they relate to social change. Its contributions included the opening of new forums that fostered genuine consultation and common understanding among diverse individuals and organizations.

In May 2021, the Office brought together prominent national voices and social actors in the race discourse for a three-day symposium, Advancing Together: Forging a Path Toward a Just, Inclusive and Unified Society.43https://news.bahai.org/story/1514/ Held exactly 100 years after the first race amity conference called for by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the event reflected the growing collaboration of the Bahá’í community with likeminded individuals and groups working to overcome racial disparities and promote justice.

Finally, as tensions heated up in the country in the summer of 2020, the National Spiritual Assembly issued a public statement addressing the current realities of race that ran in the Chicago Tribune and several newspapers across the country. It began:

“The Bahá’ís of the United States join our fellow-citizens in heartfelt grief at the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others whose lives were suddenly taken by appalling acts of violence. These heartbreaking violations against fellow human beings due only to the color of their skin, have deepened the dismay caused by a pandemic whose consequences to the health and livelihood of people of color have been disproportionately severe.”44“Forging a path to Racial Justice: A message from the Baha’is of the United States, June 19, 2020.” https://www.bahai.us/path-to-racial-justice/

As the Bahá’í community’s efforts to contribute to racial unity were advancing with newfound capacity at the grassroots and national levels, the Baha’i Chair for World Peace at the University of Maryland was breaking new ground in the examination of race in the academic sphere. As “an endowed academic program that advances interdisciplinary examination and discourse on global peace,”45http://www.bahaichair.umd.edu/aboutus the Bahá’í Chair, held by Dr. Hoda Mahmoudi, focused on “Structural Racism and the Root Causes of Prejudice” as one of the central themes of its work. Among its initiatives was the creation of a dynamic, ongoing space where experts and scholars from many disciplines—including Public Health, Sociology, History, Communications, Psychology, Technology, Government and Politics, and the Arts—brought ground breaking research from their diverse fields into a collective effort to better understand the impact of race and racial discrimination on society in pursuit of a more peaceful and equitable future.46Individuals such as Dr. Aldon Morris, Dr. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, and Dr. Jennifer Eberhardt have offered systematic, nuanced studies of how racial discrimination infects discourse while also providing solutions for how racial discrimination can end. Also, collaboration with Dr. Rayshawn Ray, a University of Maryland professor, Brookings Institution Fellow, and a Bahá’í Chair Board Member since 2018, has been particularly instrumental in shaping dialogues organized by the Chair. Applying Baha’i ideals concerning human dignity, human achievement, and human excellence, the Chair introduced into discussions on race and racial discrimination a spiritual perspective, highlighting humanity’s shared destiny. By 2021, the work initiated by the Chair nearly a decade before had garnered substantial support and high regard in the field. Dr. Mahmoudi and her colleague at the University of Maryland, Dr. Rashawn Ray, had, by 2021, initiated an ambitious project to bring together the perspectives of some of academia’s most well-respected and thought-provoking social scientists to analyze racism in America in a volume entitled, Systemic Racism in America: Sociological Theory, Education Inequality, and Social Change. Edited by Drs. Mahmoudi and Ray, the volume is scheduled to be published by Routledge Publishing later this year.

This period also witnessed countless initiatives undertaken by individuals and groups of Bahá’ís. One such initiative was the work of the Bahá’í-inspired organization, National Center for Race Amity (NCRA). Established in 2010 at Wheelock College in Massachusetts, the NCRA attracted experts on issues of racial discrimination and promoters of racial amity to its annual Race Amity Conferences and Race Amity Observations/Festivals not only in Boston but in more than a hundred other localities. By the second half of the decade, its efforts gave rise to a number of noteworthy outcomes. In 2015, for example, the Massachusetts Legislature had established an annual Race Amity Day, to be celebrated on the second Sunday of June. The following year, similar efforts by the NCRA resulted in Senate Resolution 491 passed on 10 June 2016, “Designating June 12, 2016, as a national day of racial amity and reconciliation.”47“Background for the Establishment of Race Amity Day.” https://raceamity.org/race-amity-day-festival/ And in 2018 the NCRA produced the film An American Story: Race Amity and The Other Tradition. As one of a number of individual initiatives across the US, the NCRA had an example of the continuity of the American Baha’i community’s century-long response to racial injustice and the pursuit of racial unity.

As the period of 2016 to 2021 came to a close, the American Bahá’í community could see that its learning through the series of global Plans enhanced its efforts to contribute to the cause of racial justice at different levels of society.

Conclusion: Forging a Path to Racial Justice

The identity and mission of the American Bahá’í community, fundamentally shaped by the hand of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, is intertwined with the nation’s struggle to transcend the crippling legacy of racism and its current manifestations. At each stage of its development, the Bahá’í community’s long-term commitment to apply the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh for the betterment of the world and to dismantle the insidious social ill of racism has required the development of new capacities.

Over the past quarter century, as American Bahá’ís continued to work for race unity in numerous ways, the entire Bahá’í world was set on a new path of learning about its own growth and development and its efforts to contribute to social transformation. The Bahá’í community in the United States, by the end of the period, had advanced its collective efforts to contribute to racial justice and unity at all levels of society. It had made strides in learning to build a new dynamic of community life at the grassroots—a dynamic in which individuals, families, and, in some instances, segments of a population became empowered to take ownership of the transformation of their own communities. While many of the developments described are modest and nascent, they hold promise for the long-cherished hope that the American Bahá’ís will play an increasing share in efforts to eradicate the blight of racism from their society.

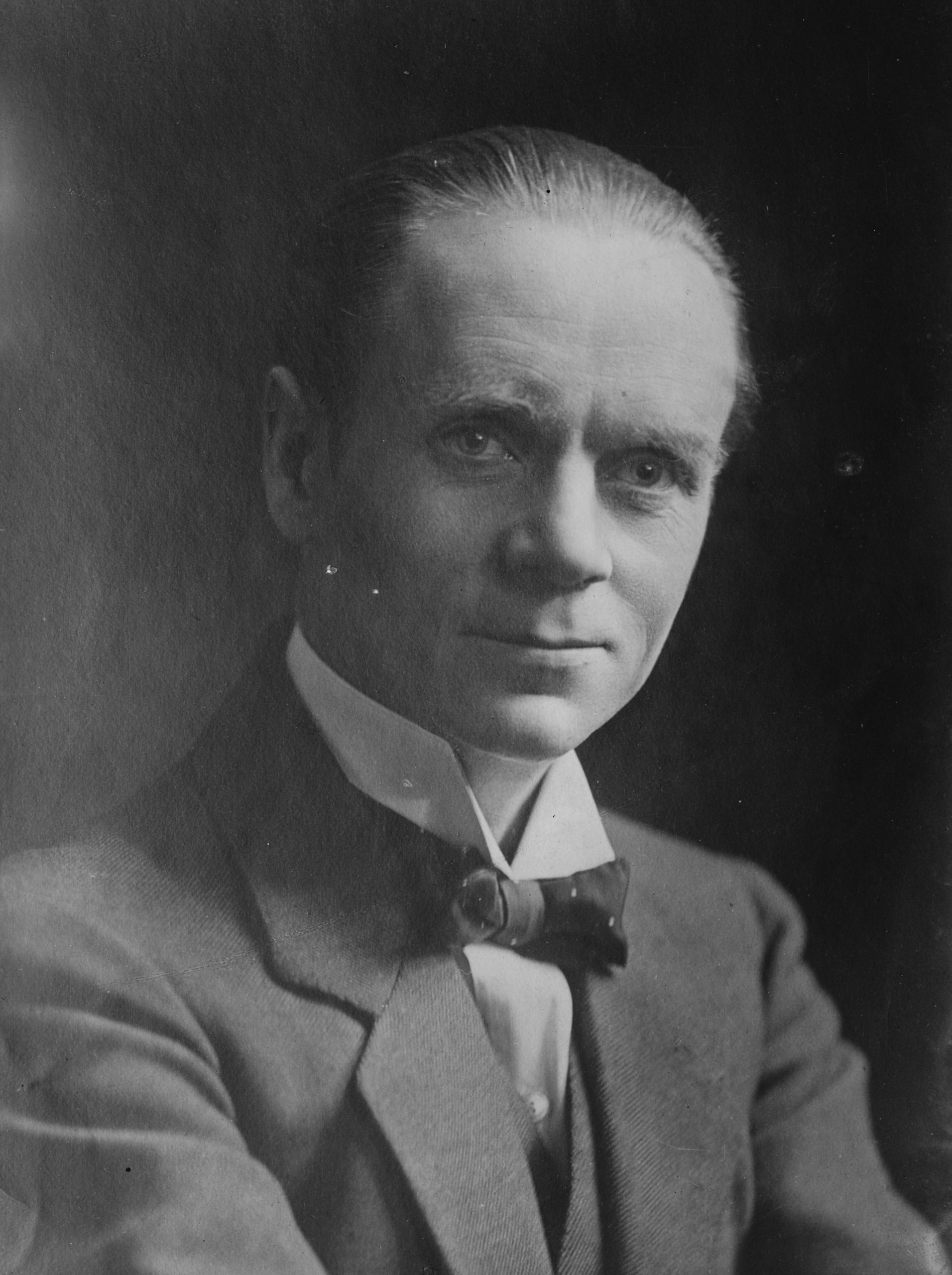

When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited Europe and North America between 1911 and 1913, the West was experiencing a period of great prosperity and peace. Europe had gone almost forty years without a battle on its soil, while the United States had spent nearly half a century healing the wounds of its civil war. The accelerating technological and industrial advances on both sides of the Atlantic were proudly displayed year after year at international expositions visited by citizens and rulers from all corners of the globe. The Western economies had reached unprecedented prosperity, which brought about changes in social organization. It is not surprising, then, that decades later, when describing the gestalt of public opinion in the years preceding the outbreak of World War I, a famous Austrian writer would state: “Never had Europe been stronger, richer, more beautiful, or more confident of an even better future.”1Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday (London: Cassell and Company, 1947), 152.

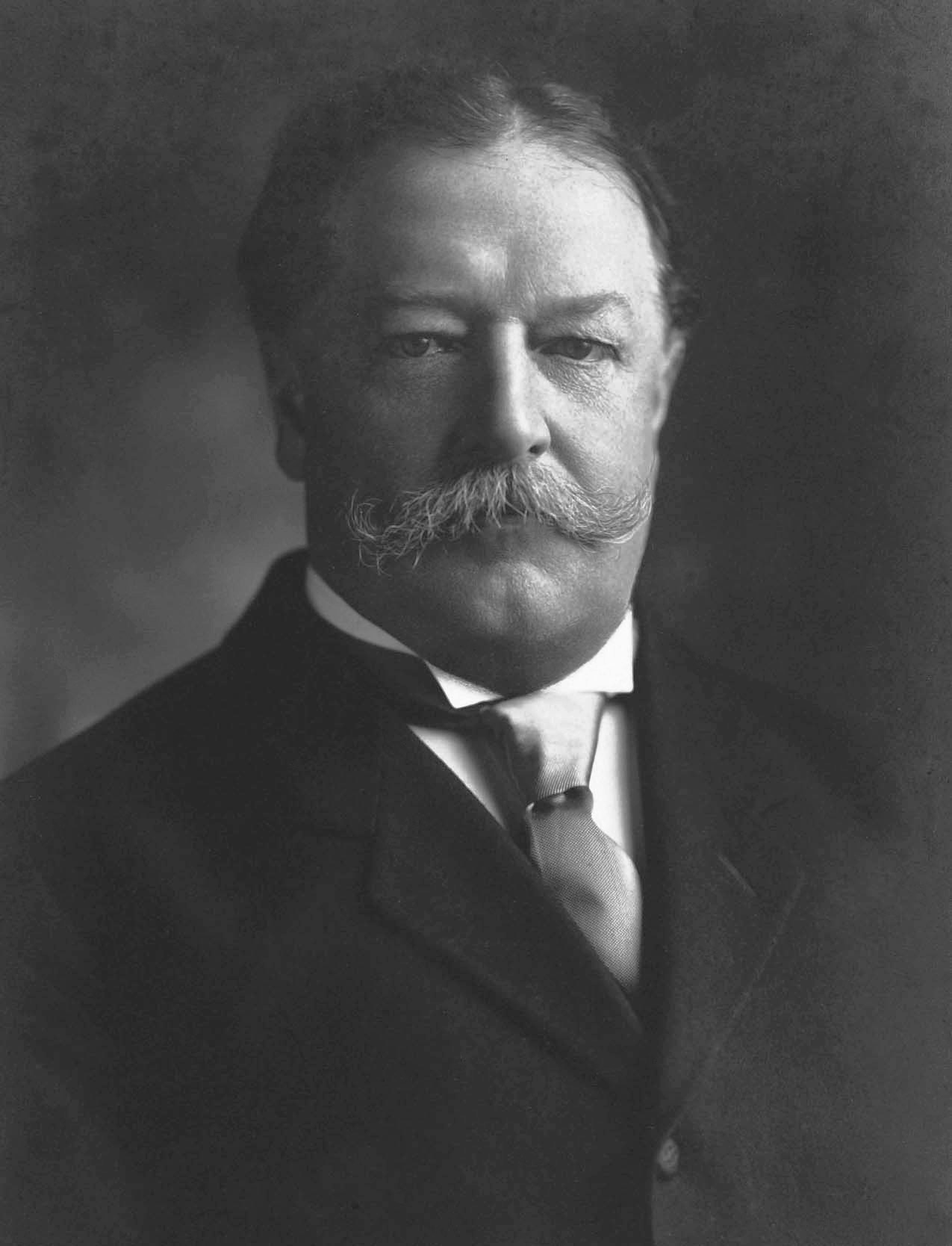

Such confidence in a peaceful and prosperous future was also supported by rapid changes in international politics. The peace conferences held in The Hague in 1899 and 1907 convinced many statesmen and prominent thinkers that the possibility of war was increasingly remote. For the first time, most of the world’s nations had collectively reached global agreements aimed at preventing war, perhaps the most promising of which was the establishment of an International Court of Arbitration. Experts in international law believed that, through arbitration, countries in conflict could resolve their disputes without resorting to arms or shedding a drop of blood. From 1899 until the outbreak of the Great War, hundreds of arbitration agreements were signed to secure peace between signatory countries. Even Great Britain and Germany signed an agreement in 1904.2For a list of arbitration treaties signed before 1912, see Denis P. Myers, Revised List of Arbitration Treaties (Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1912). Each of these advances was applauded by the many statesmen who were interested in internationalism as a path to peace. The Inter-Parliamentary Union, for example, which brought together more than 3,000 politicians from around the world, supported the court without reservation. Leaders such as President Theodore Roosevelt and his successor, William Taft, supported the court. Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who was president of the New York Peace Society—an organization that had invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to speak to its members—paid for the construction of the Peace Palace in The Hague. The building was inaugurated with great pomp in August 1913, just one year before the outbreak of the Great War.

The conviction that the solution to war lay primarily in international organization was so strong that the Hague Convention of 1907 agreed on the establishment of an International Court of Justice, which would not merely arbitrate but also administer justice and enforce international law. The details of such a court were postponed to a future Hague Conference, planned for the fateful year of 1915.

The academic world also gave credibility, through individuals’ works and studies, to this optimistic vision of the future. Scholars reasoned that a war between world powers would be so costly economically and so devastating militarily that the business world, the banks, the political parties, and public opinion in general would undoubtedly impose reason on any warlike temptation.

“The very development that has taken place in the mechanism of war has rendered war an impracticable operation,” wrote Ivan S. Bloch (1836–1902) in The Future of War. He added, “The dimensions of modern armaments and the organization of society have rendered its prosecution an economic impossibility.”3Ivan S. Bloch, The Future of War (Toronto: William Brigs, 1900), xi. Quoted by Sandi E. Cooper, “European Ideological Movements Behind the Two Hague Conferences (1889–1907)” (PhD. diss., New York University, 1967). This was the sixth volume of Bloch’s Budushchaya voina v tekhnicheskom, ekonomicheskom i politicheskom otnosheniyakh (St. Petersburg: Tipografiya I. A. Efrona, 1898).

Along similar lines, Norman Angell presented psychological and biological arguments in The Great Illusion (1911)—which was translated into more than twenty languages—to show that war would be an exercise in irrationality and suicide for the contending parties.

Optimism also spread to the peace movement, which was not only more influential than it is today but enjoyed far more resources and support. David Starr Jordan, who held a leading position in the World Peace Foundation and was the first president of Stanford University—and who invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to speak at Stanford—went so far as to ask in 1913, “What shall we say of the Great War of Europe, ever threatening, ever impending, and which never comes? Humanly speaking, it is impossible. … But accident aside—the Triple Entente lined up against the Triple Alliance—we shall expect no war.”4David Starr Jordan, What Shall we Say? Being Comments on War and Waste (Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1913), 18.

Andrew Carnegie, who had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá personally and received at least three letters from Him, would speak in similar terms a year before the war: “Has there ever been danger of war between Germany and ourselves, members of the same Teutonic race? Never has it been even imagined … We are all of the same Teutonic blood, and united could insure world peace.”5Andrew Carnegie, “The Baseless Fear of War,” The Advocate of Peace, April 1913, 79–80.

As in other spheres, many in the internationalist movement expressed absolute faith in arbitration as the ultimate means of ending war. “I am able to prove, and this is very essential,” said J. P. Santamaria, an Argentinian representative at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration in the same year that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at the distinguished event (1912), “that the majority of the Latin American republics have already exchanged treaties whereby armed conflicts become practically impossible.”6Report of the annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration (1912), p. 49.

“We believe not only that France, but Germany and Japan as well, would gladly join with England and the United States in treaties of arbitration which would make war forever impossible,” said another of the event’s speakers.7Address of Samuel B. Capen. Report of the annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration (1912), p. 159.

Whether as a result of faith in technological progress, hope in the positive influence of international policy aimed at peace, assurance in the power of the economy, or confidence in the supremacy of scientific reason, the prevailing visions for the future of humanity at the time of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to the West were strictly based on material criteria. The outbreak of World War I demonstrated the fallacy of that premise.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Radical Analysis of the Causes of War

The diagnosis of the world situation presented by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was very different from that of His contemporaries. Although on numerous occasions He referred to the need to establish international bodies with global reach and sufficient executive power to intervene in conflicts between countries,8For some comments and writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on this issue, see, for example: Makatib-i-Hadrat ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, vol. 4 (Tehran: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 121 B. E.), 161; Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978) 202:11 and 227:30; Paris Talks (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1967), 40:28; Promulgation of Universal Peace (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2012), 98:10 and 103:11. He also impressed on His audiences the urgent need to focus on the moral causes of war and the spiritual requirements for the establishment of peace.

Far from arguing that war was simply the result of deficient international organization, He asserted that it was also rooted in erroneous conceptions of the human being, which led irremediably towards division and contention. He especially warned of the dangers of racism and nationalism, which define the individual according to material parameters—bodily appearance and community of birth, respectively—and prioritize human beings and entire societies according to these factors, thus generating inequality and injustice, and fostering hatred and alienation, among human groups. He also referred to religious hatred, which He described as contrary not only to the foundation of religions but also to divine will.

“All prejudices, whether of religion, race, politics or nation, must be renounced, for these prejudices have caused the world’s sickness,” He said in a talk in Paris in 1911. Prejudice, He asserted, is “a grave malady which, unless arrested, is capable of causing the destruction of the whole human race. Every ruinous war, with its terrible bloodshed and misery, has been caused by one or other of these prejudices.”9‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 45:1. Ibid., p. 159.

“Man has laid the foundation of prejudice, hatred and discord with his fellowman,” He explained in 1912 in a speech at a Brooklyn church, “by considering nationalities separate in importance and races different in rights and privileges.”10‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 82:11.

“As long as these prejudices prevail, the world of humanity will not have rest,” He wrote years later.11‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 227:10. This is part of one of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s communications to the Central Organization for a Durable Peace, in The Hague.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá rejected the premises on which each of these models of thought were based. He denied, for example, the objective existence of races, stating instead that “humanity is one kind, one race and progeny, inhabiting the same globe.”12‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “Address to the International Peace Forum, New York, 12 May 1912,” Promulgation of Universal Peace, 47:6. He also denied that nations are natural realities, referring to national divisions as “imaginary lines and boundaries.”13‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 98:6. He denied any essential differences between religions, since they all have a common origin, share the same spiritual foundations, and are essentially one and the same. Furthermore, He affirmed that religious differences are due to “dogmatic interpretation and blind imitations which are at variance with the foundations established by the Prophets of God,”14‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 110:15. stressed that these aspects of religion must disappear, and even went so far as to declare that “if religion be the cause of enmity surely the lack of religion is better than its presence.”15“Abdul Baha Gives His Impressions of New York”, The Sun (New York), 7 July 1912, 8.

He spoke at a time when the ideologies characteristic of a culture of inequality (racism, nationalism, sexism, and so on) were on the rise, gradually pushing humanity into what would be the bloodiest and most catastrophic century of its history. Racism, for example, was endorsed by a significant portion of the scientific community of the time and was firmly established in large parts of the world in the form of discriminatory and segregationist laws. It was even undergoing a major transformation equipped by new “scientific” techniques—such as craniometry, phrenology, and physiognomy—that inspired new and abhorrent “social reform” initiatives, such as eugenics and racial hygiene. Nationalism, for the first time in history, had instilled in the majority of humanity the vision of a globe divided into parcels of land defined by races, cultures, and languages. It drove imperialist and colonialist policies, while colonialism, in turn, exported nationalism, imposing previously nonexistent categories and definitions on citizens and territories worldwide. At the same time, longstanding religious conflicts were still very much present, reviving old grievances and warlike moods—as exemplified by the chronic problems in the Balkans, which were in full swing when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited the West.

Even individuals and organizations with noble goals held such doctrines of inequality. Many pacifists, for example, saw war not so much as a moral problem, but as a biological one. Influenced by racism and social Darwinism, they based their criticism of war on the argument that “fit” men were sent to the battlefield, where they died, while “unfit” men stayed behind and reproduced. The consequence of such a phenomenon, they believed, was “racial weakening.”

“Only the man who survives is followed by his kind,” wrote the aforementioned David Starr Jordan. “The man who is left determines the future. From him springs the ‘human harvest’ …”16David Starr Jordan, War’s Aftermath (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), xv.

Along the same lines, Norman Angell also criticized colonial expansion in biological terms, arguing that domination and contact between civilizations prolonged the life of “weak races.”

“When we ‘overcome’ the servile races,” Angell reasoned in his internationally best-selling book, “far from eliminating them, we give them added chances of life by introducing order, etc., so that the lower human quality tends to be perpetuated by conquest by the higher. If ever it happens that the Asiatic races challenge the white in the industrial or military field, it will be in large part thanks to the work of race conservation, which has been the result of England’s conquest …”17Norman Angell, The great illusion (London: William Heinemann, 1910), 189. In 1933 Angell would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Benjamin Trueblood, secretary of the American Peace Society, who met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Washington, D.C., raised the possibility of a future world federation as a consequence of a “great racial federation” in the Anglo-Saxon world.18Benjamin Trueblood, The Federation of the World (Boston: The Riverside Press, 1899), 132. This idea was similar to that put forward by Andrew Carnegie.

In this context, we can understand—with the perspective provided by the passage of more than a century since His travels—that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s warnings about the causes of war could not be understood by societies immersed in paradigms of thought totally different from the ones He presented.

And just as the meanings and diagnoses of the causes of war differed between those provided by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the dominant discourses of the time, so did proposals for the establishment of peace. As explained, the international community had placed its hope in legislation and international institutions as mechanisms for ensuring peace; some pacifists sincerely believed that such changes also required the racial hegemony of certain peoples. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, however, emphasized a completely different concept: peacemaking would only be possible when humanity reached the understanding that it is one and acted in accordance with this principle. He brought this idea forward in a great number of His talks. For instance, in Minneapolis, He stated that human beings “must admit and acknowledge the oneness of the world of humanity. By this means the attainment of true fellowship among mankind is assured, and the alienation of races and individuals is prevented … In proportion to the acknowledgment of the oneness and solidarity of mankind, fellowship is possible, misunderstandings will be removed and reality become apparent.”19‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 105:6.

By making such a statement, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá presented His listeners with a radical challenge. The recognition of the oneness of the human race implies, on one hand, the acceptance that there is a primordial identity common to all human beings, which goes beyond any physical or accidental diversity between individuals. It also implies the abandonment of any vision of the human being—foundational to beliefs such as racism, sexism, unbridled nationalism, and religious exclusivism—that justifies human inequality. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approach, therefore, clashed head-on with the discourses of the time and the materialistic premises that underpinned them.

The Great War

Although ‘Abdu’l-Bahá praised on numerous occasions progress that humanity was experiencing, for example in economics, politics, science, and industry, He also warned that material progress alone would not be capable of bringing true prosperity without a commensurate spiritual advancement.

“Material civilization concerns the world of matter or bodies,” He explained during His visit to Sacramento, “but divine civilization is the realm of ethics and moralities. Until the moral degree of the nations is advanced and human virtues attain a lofty level, happiness for mankind is impossible.”20‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 113:15.

From this perspective, the ideologies of inequality that permeated all areas of human endeavor were totally incapable of promoting lasting peace, including in movements that promoted pacifism, internationalism, and diplomacy.

“The Most Great Peace cannot be assured through racial force and effort,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained in an address in Pittsburgh:

It cannot be established by patriotic devotion and sacrifice; for nations differ widely and local patriotism has limitations. Furthermore, it is evident that political power and diplomatic ability are not conducive to universal agreement, for the interests of governments are varied and selfish; nor will international harmony and reconciliation be an outcome of human opinions concentrated upon it, for opinions are faulty and intrinsically diverse. Universal peace is an impossibility through human and material agencies; it must be through spiritual power …

For example, consider the material progress of man in the last decade. Schools and colleges, hospitals, philanthropic institutions, scientific academies and temples of philosophy have been founded, but hand in hand with these evidences of development, the invention and production of means and weapons for human destruction have correspondingly increased …

If the moral precepts and foundations of divine civilization become united with the material advancement of man, there is no doubt that the happiness of the human world will be attained and that from every direction the glad tidings of peace upon earth will be announced.21‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 44:13–15.

Based on this premise, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá challenged a falsely optimistic vision of the world, noting that, if the moral and spiritual dimensions of social reality were also assessed, it would become apparent that the world was experiencing a moment of great decadence. “If the world should remain as it is today,” He said in Chicago in 1912, “great danger will face it.”22‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 104:1.

“Observe how darkness has overspread the world,” he explained in Denver:

In every corner of the earth there is strife, discord and warfare of some kind. Mankind is submerged in the sea of materialism and occupied with the affairs of this world. They have no thought beyond earthly possessions and manifest no desire save the passions of this fleeting, mortal existence. Their utmost purpose is the attainment of material livelihood, physical comforts and worldly enjoyments such as constitute the happiness of the animal world rather than the world of man.23‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 107:4.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá warned of the acute risk of an impending international conflict on no less than seventeen occasions. “Europe itself,” He said in Paris in 1911, “has become like one immense arsenal, full of explosives, and may God prevent its ignition—for, should this happen, the whole world would be involved.”24“Apostle of Peace Here Predicts an Appalling War in the Old World,” The Montreal Daily Star, 31 August 1912, 1. [The following includes numerous incomplete citations—most need page or publisher data] For other comments about the possibility of a war, see Promulgation of Universal Peace, 3:7, 103:11, 108:1, 114:2; ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on Divine Philosophy (Boston: The Tudor Press, 1918), 95. “The Awakening of Older Nations,” The Advertiser (Montgomery, Alabama), 7 May 1911; “Turks Prisoner for 40 Years,” The Daily Chronicle (London), Western Edition, 17 January 1913, 1; “Abdul Baha’s Word to Canada,” Toronto Weekly Star, 11 September 1912; Montreal Daily Star, 11 September 1912, 2; “Abdul Baha’s Word to Canada,” Montreal Daily Star, 11 September 1912, 12; “Persian Peace Apostle Predicts War in Europe,” Buffalo Courier, 11 September 1912, 7; “Message of Love Conveyed by Baha,” Buffalo Enquirer, 11 September 1912, 5; “Urges America to Spread Peace,” Buffalo Commercial, 11 September 1912, 14; “Abdul Baha an Optimist,” Buffalo Express, 11 September 1912, 1; “Bahian Prophet Returns After a Trip to Coast,” Denver Post, 29 October 1912, 7.

Despite this and other explicit warnings, His audiences remained for the most part unmoved. Confidence in material well-being weighed more heavily on public opinion than His diagnosis of the moral state of the world.25‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 34:5.

He reiterated his warnings in the years between the end of World War I and His passing in 1921. In His correspondence, He explained that a second world conflagration was imminent, despite the terror caused by the first world war and the enormous progress that had been made in international governance with the establishment of the League of Nations.

“Although the representatives of various governments are assembled in Paris in order to lay the foundations of Universal Peace and thus bestow rest and comfort upon the world of humanity,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote in 1919, “yet misunderstanding among some individuals is still predominant and self-interest still prevails. In such an atmosphere, Universal Peace will not be practicable, nay rather, fresh difficulties will arise.”26‘Abdu’l-Bahá, tablet to David Buchanan of Portland, Oregon, Star of the West, 28 April 1919, 42.

“For in the future another war, fiercer than the last, will assuredly break out,” He wrote in 1920. “Verily, of this there is no doubt whatever.”27Letter to Ahmad Yazdaní, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 228:2.

In another letter sent the same year, He was even more explicit. After presenting—as He had done in His addresses in the West—some of the spiritual requirements for the establishment of peace, He closed by enumerating some of the elements that would eventually lead humanity to World War II just nineteen years later:

The Balkans will remain discontented. Its restlessness will increase. The vanquished Powers will continue to agitate. They will resort to every measure that may rekindle the flame of war. Movements, newly born and worldwide in their range, will exert their utmost effort for the advancement of their designs. The Movement of the Left will acquire great importance. Its influence will spread.28Letter sent through Martha Root, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 202:14.

The Birth of a New Society

No reader of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá should be tempted to think that, in His exposition of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, He moved only within the theoretical realm. On the contrary, while His efforts to spread Bahá’u’lláh’s message were enormous, His endeavors to bring those teachings into the realm of action were colossal. In a conversation in London, for example, referring to one of the many congresses held at the time, bringing together philanthropists eager to improve the world, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stressed, “To know that it is possible to reach a state of perfection, is good; to march forward on the path is better. We know that to help the poor and to be merciful is good and pleases God, but knowledge alone does not feed the starving man …”29‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982)60.

Throughout His ministry, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá directed the Bahá’í community to make itself a model of the future society foretold by Bahá’u’lláh—one through which humanity might witness the transformations that accompany the application of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings to social and interpersonal relations.

In several of His talks, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described the Bahá’ís of Persia (now Iran) as one such example. They lived in an environment in which religious segregation was a social reality. Zoroastrians, Jews, Christians, and other religious minorities lived in isolation from their Muslim neighbors and also separated from each other. Being considered impure beings (najis), the minority groups were subject to strict rules that regulated not only their relations with Muslims, but also the jobs they performed and even the clothes they wore. In this environment, bringing people from different religious backgrounds together in the same room was not just taboo, but unthinkable. Despite this, the Bahá’í community in Persia managed to become—first under the guidance of Bahá’u’lláh and then of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá—a cohesive group comprising people from all religious backgrounds. Having in common their faith in the transformative capacity of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, they were able to set aside prejudices inherited from the surrounding society and their ancestors and work together to improve conditions for their fellow citizens. It was not long before Persian Bahá’ís—men and women alike—learned to make decisions collectively and to implement them without regard for different backgrounds or genders.

Such a change not only resulted in the unprecedented growth of the Bahá’í community, but also in the proliferation of numerous social and charitable projects throughout the country. For example, during the ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the Persian Bahá’ís managed to establish no less than twenty-five schools, including some of the country’s first schools for girls. Beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century, Bahá’ís in Persia also established health centers in several cities, including the Sahhat Hospital in Tehran, which followed the instructions of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to include in its mission statement that it would provide “service to mankind, regardless of race, religion and nationality,” a revolutionary statement at that time and place.30Seena B. Fazel and Minou Foadi. “Baha’i health initiatives in Iran: a preliminary survey,” The Baha’is of Iran, eds. Dominic P. Brookshaw and Seena B. Fazel (New York: Routledge, 2008), 128.

While this was happening in the East, American Bahá’ís were working under the leadership of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to racially integrate their community.

“Strive with heart and soul in order to bring about union and harmony among the white and the black and prove thereby the unity of the Bahá’í world wherein distinction of color findeth no place, but where hearts only are considered,” He wrote in one of His letters to them. “Variations of color, of land and of race are of no importance in the Bahá’í Faith; on the contrary, Bahá’í unity overcometh them all and doeth away with all these fancies and imaginations.”31Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 75.

He also exhorted them to “endeavor that the black and the white may gather in one meeting place, and with the utmost love, fraternally associate with each other.”32Bonnie J. Taylor and National Race Unity Conference, eds., The Power of Unity (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1986), 30.

“If it be possible,” He wrote on another occasion, “gather together these two races—black and white—into one Assembly, and create such a love in the hearts that they shall not only unite, but blend into one reality. Know thou of a certainty that as a result differences and disputes between black and white will be totally abolished.”33The Power of Unity, 28.

The process by which the Bahá’í community in the United States became a model of racial integration was accelerated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to North America—through His personal example, His participation in integrated meetings, His encouragement to Bahá’ís who held them, and His constant instructions in all the cities He visited on the issue of race.

After the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá commissioned Agnes Parsons, a Bahá’í and member of high society in Washington, D.C., to organize the first Race Amity Conference, which took place in May 1921. The event, promoting racial unity and harmony, triggered a national movement that replicated the Conference in different parts of the United States in the following years, involving not only the American Bahá’í community, but also many other organizations and societal leaders. The result of these efforts was the transformation of the Bahá’í community into a group actively engaged in banishing the racial prejudices so present in its surrounding society.

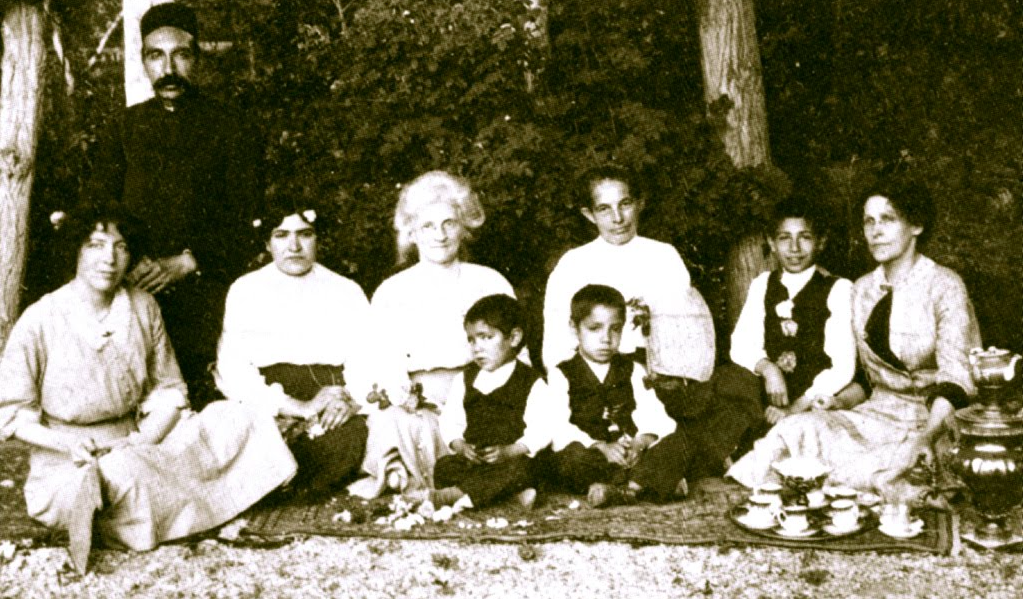

In His efforts to demonstrate, through the global Bahá’í community, empirical proof that unity and freedom from prejudice leads to peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also promoted collaborative ties between the Bahá’ís of the West and the East. Beginning in the early twentieth century, He encouraged Persian Bahá’ís to travel to Europe and North America, and Western Bahá’ís to visit Persia or India. He promoted communications between Bahá’í communities. For example, the Star of the West, the journal of the Bahá’ís of the United States, included a section in Persian and was regularly sent to Persia. As development projects in Persia grew and became more complex, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged Western Bahá’ís to support them and extend assistance. As a result, in 1909, Susan Moody, M.D., moved to the country to work at the Sahhat hospital in Tehran. Moody was followed by other Bahá’ís, including teacher and school administrator Lilian Kappes, nurse Elizabeth Stewart, and fellow doctor Sarah Clock. In 1910, the Orient-Occident Unity was founded with the aim of establishing collaboration in different fields between the people of Persia and the United States.34This name was adopted in 1912. Its earliest name was the Persian-American Educational Society. The work of this organization involved not only many Bahá’ís, but other prominent organizations and individuals.

All these transformations provided glimpses of the social implications of the principles promulgated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and presented examples of the effects generated by applying in the field of action the principle of world unity and the conception of the human being enunciated by Bahá’u’lláh.

Addressing the Immediate Needs

On 24 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austrian-Hungarian Empire, was assassinated in Sarajevo. A few weeks later, the European powers were at war, and the disaster predicted by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá only a few years earlier became a reality.

The Ottoman regions of Syria and Palestine did not escape the dire consequences of the conflagration. The area was hit by famine caused by pillaging Ottoman troops as they crossed the territory to reach Egypt, where they were defending the strategic Suez channel. In the Haifa area, circumstances were particularly complicated. The local population held diverging alliances. The Arabs were divided between those sympathizing with the French and those supporting the Ottoman Empire, while the members of the large German colony supported their own country. These divisions caused tension and sometimes produced violence. The city was also the target of bombings from the sea. Thus, within a few weeks, Haifa and its surroundings experienced a rapid transition from a relative state of peace to severe insecurity associated with a humanitarian crisis. The conflict caused acute needs that required urgent attention.

Before the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had taken steps that would allow Him to ameliorate these conditions. His most visible contribution was to provide food for the people of Haifa and its vicinity. At the beginning of the twentieth century, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had established various agricultural communities around the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan Valley, with the most important one in ‘Adasiyyih, in present-day Jordan. During the hardest years of the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent shipments of foodstuffs from this location to Haifa, using some two hundred camels for just one trip, which gives an idea of the scale of the aid.35For more information on this, see Iraj Poostchi, “Adasiyyah: A Study in Agriculture and Rural Development,” Bahá’í Studies Review 16 (2010), 61–105. To distribute the food within the population, He organized a sophisticated rationing system using vouchers and receipts to ensure that the food reached all those in need while preventing abuse.

“He was ever ready to help the distressed and the needy,” a witness was quoted as saying in 1919 in London’s Christian Commonwealth:

… often He would deprive himself and his own family of the necessities of life, that the hungry might be fed and the naked be clothed. … For three years he spent months in Tiberias and Adassayah, supervising extensive works of agriculture, and procuring wheat, corn and other food stuffs for our maintenance, and to distribute among the starving Mohamedan and Christian families. Were it not for his pre-vision and ceaseless activity none of us would have survived. For two years all the harvests were eaten by armies of locusts. At times like dark clouds they covered the sky for hours. This, coupled with the unprecedented extortions and looting of the Turkish officials and the extensive buying of foodstuffs by the Germans to be shipped to the “Fatherland” in a time of scarcity, brought famine. In Lebanon alone more than 100.000 people died from starvation.36“News of Abdul Baha,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 22 January 1919, 196. Text in Amín Egea, The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2 (Oxford: George Ronald, 2018), 427–428.

“Abdul Baha is a great consolation and help to all these poor, frightened, helpless people,” another report read.37“Bahai News,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 3 March 1915, 283. Text in The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2, 410.