Humanity is gripped by a crisis of identity, as various peoples and groups struggle to define themselves, their place in the world, and how they should act. Without a vision of shared identity and common purpose, they fall into competing ideologies and power struggles. Seemingly countless permutations of “us” and “them” define group identities ever more narrowly and in contrast to one another. Over time, this splintering into divergent interest groups has weakened the cohesion of society itself.1Universal House of Justice, letter to the Bahá’ís of the World, 18 January 2019. On humanity’s crisis of identity and the principle of human oneness, see also: Universal House of Justice, letter to the Followers of Bahá’u’lláh in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1 November 2022.

—The Universal House of Justice

The “crisis of identity” described by the Universal House of Justice is one of the defining features of the present moment. Questions of identity and belonging have surged to prominence in recent years, finding expression in virtually every aspect of collective life. As the forces of our decidedly global age challenge the boundaries, both literal and figurative, that define group identities, the secure sense of belonging these identities have traditionally supplied is increasingly frustrated or lost, resulting in confusion, insecurity, conflict, and ever more forceful assertions of difference. Paradoxically, even as the need for a deeply felt sense of human oneness has grown more obvious, categories of “us” and “them” have multiplied and become more salient around the globe.

Confronted with humanity’s crisis of identity, some thinkers have proposed the reimagination of national identity. A newly enlightened and capaciously inclusive form of nationalism, they suggest, can provide a shared context of belonging within which various narrower identities and attachments can be reconciled.2For example, see: Amy Chua, Political Tribes: Group Instincts and the Fate of Nations (New York: Penguin Press, 2018); Francis Fukuyama, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018); Mark Lilla, The Once and Future Liberal (New York: Harper, 2017); Yascha Mounk, The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and What We Can Do About It (New York: Penguin Press, 2022). But solutions rooted in national identity, or in other familiar concepts such as liberal democracy, are struggling to resolve the crisis.

From the perspective of the Bahá’í teachings, the solution to our crisis of identity lies in the genuine and deeply felt recognition of human oneness. Specifically, the Bahá’í writings suggest that only a collective identity3As social psychologists explain, identity is a (self-)categorization that holds significant emotional meaning, typically entailing thick ties of empathy, solidarity, belonging, and love. Ties of identity thus differ from other, more cerebral or emotionally thin bonds of universal human connection such as those that might result, for example, from a rational commitment to the equal moral worth of all persons. See Monroe, K. R., Hankin, J., & Van Vechten, R.B. (2000). The psychological foundations of identity politics. The Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 419-447. 2000. rooted in the oneness of humankind can resolve our present crisis and fundamentally relieve the various long-standing tensions that surround it. The previously cited passage from the Universal House of Justice goes on to elaborate this point:

“Rival conceptions about the primacy of a particular people are peddled to the exclusion of the truth that humanity is on a common journey in which all are protagonists. Consider how radically different such a fragmented conception of human identity is from the one that follows from a recognition of the oneness of humanity. In this perspective, the diversity that characterizes the human family, far from contradicting its oneness, endows it with richness. Unity, in its Bahá’í expression, contains the essential concept of diversity, distinguishing it from uniformity. It is through love for all people, and by subordinating lesser loyalties to the best interests of humankind, that the unity of the world can be realized and the infinite expressions of human diversity find their highest fulfilment.”4Universal House of Justice, letter to the Bahá’ís of the World, 18 January 2019. On humanity’s crisis of identity and the principle of human oneness, see also: Universal House of Justice, letter to the Followers of Bahá’u’lláh in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1 November 2022.

The notions of identity and human oneness reflected in this passage, and indeed throughout the Bahá’í writings, present a radical departure from the way these concepts are frequently understood in contemporary thought and discourse. Many prominent conceptions of our shared humanity, and in particular, those that emerge from the predominant intellectual frameworks of the West, are widely deemed homogenizing. They are also critiqued for being too far removed from the texture of everyday life to hold any relevance for the communities and relationships to which people immediately belong. The Bahá’í teachings offer a different vision. Far from threatening or contradicting the essential diversity of humankind, the Bahá’í writings suggest that a universal human identity is uniquely equipped to ensure the fundamental security and flourishing of our particular (i.e., narrower) identities, communities, and affiliations. This article considers why and how the Bahá’í expression of human oneness resolves both the collective crisis of identity we currently face and the long-assumed tension between the oneness and the diversity of humankind.

Humanity’s Crisis of Identity: Two Underlying Tensions

It would be helpful to begin by more closely examining the crisis itself. Two long standing tensions, or apparent contradictions, underlie humanity’s crisis of identity and complicate its resolution.

The first tension pertains directly to the nature of traditional group identities5In this article, the terms “group identity,” “collective identity,” “social identity,” and “identity” are used interchangeably. See footnote 3 for a brief explanation of what identity entails. themselves. As the philosopher Martha Nussbaum explains in reference to the two-faced Roman god of duality, collective identities are “Janus-faced”: they are characterized by two contrasting aspects in chronic tension.6M. C. Nussbaum, “Toward a globally sensitive patriotism,” Daedalus 137, no. 3 (2008): 78-79. On the one hand, our traditional “bounded” identities—that is, identities that include some and exclude others—are deeply susceptible to instability, conflict, and destructiveness. Whether in the dividing lines of contemporary society or in the most catastrophic injustices of human history, collective identities can reveal an exceedingly ugly face. Observing the tensions that surround group identities, the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah declares them “horsemen of the apocalypses from apartheid to genocide.”7K. A. Appiah, The lies that bind: Rethinking identity (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2018), xvi.

On the other hand, the diversity embodied in our bounded social identities is vital. At the aggregate level, various forms of diversity are essential to the strength, stability, and flourishing of social systems.8For example: A. L. Antonio, et al., “Effects of racial diversity on complex thinking in college students,” Psychological Science 15, no. 8 (2004): 507-510; F. Arbab, “Promoting a discourse on science, religion, and development,” in The lab, the temple, and the market: Reflections at the intersection of science, religion, and development, ed. S. Harper (Ottawa: International Development Research Center, 2000), 149-237. Shared identities, furthermore, bind us together in social and moral enterprises, providing a basis for community, collective action, and mutual support. At a more personal and subjective level, our particular experiences and perspectives constitute important parts of our self-concept as human beings: they legitimately yearn for recognition, inclusion, and expression.

This dual nature of collective identity is also suggested in the Bahá’í writings. Shoghi Effendi, for instance, distinguishes unbridled nationalism from a “sane and legitimate patriotism,”9Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Baha’u’llah. Available at www.bahai.org/r/895919188 and the Universal House of Justice describes “a love of one’s country that cannot be manipulated” and that “enriches one’s life.”10Universal House of Justice, letter to the Bahá’ís of Iran, 2 March 2013. Universal House of Justice, letter to the World’s Religious Leaders, April 2002. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá makes this duality more explicit. “[D]ifferences, He writes, “are of two kinds. One is the cause of annihilation and is like the antipathy existing among warring nations and conflicting tribes who seek each other’s destruction … The other kind, which is a token of diversity, is the essence of perfection …”11‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Available at www.bahai.org/r/583780535

These two sides of our traditional bounded identities leave them in a state of chronic tension and instability which has, to date, stubbornly evaded resolution. Social identities are perpetually vulnerable to destructiveness and conflict. And yet, we cannot live without them.

The tension that characterizes bounded identities is amplified by their relationship to forces and movements that are unbounded. Economic globalization in its various forms, the heightened ease of transborder communication, the growing universality of our moral intuitions, the expanding consciousness of human oneness and interdependence more broadly, not to mention the countless interdependencies that propagated a deadly virus across the globe, are all widely thought to threaten the security of our traditional identities and affiliations.12W. Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books, 2010); C. Kinnvall “Globalization and religious nationalism: Self, identity, and the Search for ontological security,” Political Psychology 25, no. 5 (2004): 741-767. Put differently: the legitimate yearning for rootedness and belonging is challenged by the porousness, fluidity, and expanded consciousness of an increasingly global age. The insecurity induced by these “universalizing” forces thus results in a more acutely felt yearning for the sense of rootedness traditional identities provide, as well as in the related impulse to bolster the security of these identities by sharpening the boundaries that define them. In other words, as our shared consciousness of the physical, social, moral, and economic space we inhabit as human beings is stretched to include the entire planet, humanity’s collective ambivalence toward its bounded identities both intensifies and becomes increasingly expressed in a second, broader tension between the universal and the particular—between the pull of bounded identities and attachments, on the one hand, and that of universalist forces and aspirations, on the other. This stubborn tension has led the political philosopher Seyla Benhabib to conclude, “Our fate, as late-modern individuals, is to live caught in the permanent tug of war between the vision of the universal and the attachments to the particular.”13S. Benhabib, The Rights of Others: Aliens, Residents and Citizens, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 16.

At the heart of humanity’s crisis of identity, therefore, lies a key question: Can humanity’s fundamental oneness be reconciled with its essential diversity? And can such a reconciliation be achieved at the deepest levels of human identity and meaning? The answer proclaimed in the Bahá’í writings, as we have seen, is unequivocally affirmative: it is through the deeply felt recognition of human oneness that the diversity of humankind thrives and finds its highest fulfillment. Why might an identity rooted in the oneness of humankind be uniquely equipped to protect and promote its diversity?

Unique Features of an Identity Rooted in the Oneness of Humankind

To begin answering this question, I suggest that a collective identity genuinely rooted in the oneness of humankind is qualitatively different than every other social identity because of at least two distinguishing features. These unique features, in turn, enable a universal human identity to stabilize and empower14Of course, not all identities—and certainly not every aspect of every identity—should be preserved or empowered. Identities (or aspects of them) that cannot be reconciled with the principle of human oneness (for instance, those rooted in racial superiority or in some other form of antagonism toward others) must ultimately be abandoned. On this important point, see also footnotes 32 and 48 below. our particular identities in ways that other overarching affiliations—nationality, for example—cannot.

The first feature that distinguishes an identity rooted in the oneness of humankind is rather obviously that it is non-exclusionary. Insofar as human beings and their communities are concerned, an identity genuinely rooted in our common humanity has no bounds of exclusion or parameters of otherness; it literally has no “other.”15What I wish to do in this article is to move away from the defensive posture that cosmopolitan theorists and other proponents of universalism often take to refute objections, and instead, lean into the notion of non-exclusion to identify its implications. Much has been written to question the possibility and meaningfulness of such a collective identity and, at a theoretical level at least, this skepticism has been ably addressed elsewhere. See, for example, A. Abizadeh, “Does collective identity presuppose and other? On the alleged incoherence of global solidarity,” American Political Science Review 99, no. 1 ,(2000): 45-60. This stands in contrast to all traditional social identities which, by definition, have outsiders, and are thus inescapably bounded and exclusionary.

I hasten to note that a non-exclusionary human identity need not cast humanity in opposition to non-human life on the planet, nor must it entail a sharp separation of human beings from their physical environment, precluding, for instance, the notion that we share a type of oneness with our ecosystem(s).16For an illuminating discussion of this topic, see P. Hanley, Eleven, (Victoria, Canada: Friesen Press, 2014), especially Chapter 12. Indeed, a genuinely non-exclusionary human identity should lead to a deeper appreciation of our broader interdependence, rather than to a destructive anthropocentricism, which is often an expression of the very same attitudes and predispositions that animate the exclusion, oppression, and destruction of human life on the planet.17Hanley, Eleven, 280. See also: Akeel Bilgrami, Secularism, Identity, and Enchantment (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014), Chapter 5.

The second distinguishing feature of a genuinely universal human identity pertains to the nature of the commonality on which it is based. Consider that, as scientific studies widely confirm, virtually all other group identities are ultimately socially constructed.18W.C. Byrd, et al, “Biological determinism and racial essentialism: The ideological double helix of racial inequality,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 661, no. 1 (2015): 8-22. This is not to say, of course, that these identities are not real, whether in their objective, material consequences, or in humanity’s subjective experience and valuation of them. It is to observe, rather, that the commonalities in which they are grounded are contingent (i.e., dependent) on a range of social constructs and impermanent socio-historical phenomena, for example, on fluid beliefs about social and biological reality, on the frequently contested details of history, on socially constructed parameters of membership, and tragically, on shared experiences of oppression and injustice.19Given its biological distinctions, one might object that an identity based on gender is an exception to this observation. But a very large proportion of what constitutes gender—our ideas about what different genders are, and how members of each should behave and feel, for example—is socially constructed. As the Universal House of Justice writes in a letter to the Bahá’ís of Iran dated 2 March 2013: “The rational soul has no gender or race, ethnicity or class…” For a related discussion, see also: Appiah, The lies that bind, Chapter 1. In this sense, then, the contingency of other collective identities is inescapable.

Strikingly, more than a hundred years ago, when the socially constructed nature of humanity’s dividing lines was far from obvious, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá made these observations explicit. As he explained, “These boundaries and distinctions are human and artificial, not natural and original.”20‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Foundations of World Unity, 23. And elsewhere: “Religions, races, and nations are all divisions of man’s making only …”21‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 131. Indeed, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá elaborated on the inherent contingency and impermanence of the various identities and affiliations that traditionally bind human beings together:

“In the contingent world there are many collective centers which are conducive to association and unity between the children of men. For example, patriotism is a collective center; nationalism is a collective center; identity of interests is a collective center; political alliance is a collective center; the union of ideals is a collective center, and the prosperity of the world of humanity is dependent upon the organization and promotion of the collective centers. Nevertheless, all the above institutions are, in reality, the matter and not the substance, accidental and not eternal—temporary and not everlasting. With the appearance of great revolutions and upheavals, all these collective centers are swept away.”22‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Tablets of the Divine Place, 14: Tablet to the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada.

Drawing on the Bahá’í writings, this article posits that, in contrast to the necessarily contingent basis of all other identities, the basis of a universal human identity need not be socially constructed or contingent. Such an identity, rather, can be rooted in the non-contingent and ultimately investigable reality of human oneness.

This second unique and distinguishing feature of an identity authentically rooted in the oneness of humankind I will call its non-contingency. Specifically, by positing that the basis of a genuinely universal human identity is non-contingent, I take for granted first, that there is something distinctive and non-contingent that only and all human beings have in common;23As this article later discusses, the Baha’i writings offer a spiritual understanding of this human commonality, recognizing it as the human soul. and, second, that the expressions of this human commonality or “core”—expressions in the form, for example, of common yearnings, vulnerabilities, and experiences—are such that human beings, whatever their particular context, can come to recognize that a distinctive and non-contingent human commonality exists.24For the argument that follows to hold, a third premise is also needed, namely, that human beings are able to readily recognize the humanness of another without a widely articulated consensus on the content of our humanity. In other words, there is, or there can be, a reasonably widespread intuitive consensus about who falls within the community of human beings. ,25It is worth highlighting an important distinction between the non-contingent basis of a human collective identity (posited above) and the empirically contingent process whereby any social identity, including a universal one, is formed. To posit that a collective human identity can be rooted in a set of features that are not contingent on socio-historical constructs is not to say that the process through which such an identity emerges and becomes expressed—the process whereby we come to recognize and articulate our oneness and interdependence as human beings, for example, or the process that finally exposes our need for an identity based on this recognition—is not socially, materially, and historically contingent. Indeed, it is precisely the empirical conditions of our time, and the surge of historically contingent forces that shape them, which make the recognition of such a collective identity possible.

Not every possible basis of unbounded human affiliation will meet the criteria of genuine (or authentic) non-contingency. The article returns to this point in various ways below, especially when it considers what constitutes a genuinely non-contingent basis for collective identity from the Bahá’í perspective.

The sections that immediately follow, however, aim to show that when taken together, the two distinguishing features of a universal social identity posited above—that is, its non-exclusionary and potentially non-contingent basis—carry deep and far-reaching implications.

A Source of Fundamental Security

What implications follow from the non-exclusionary and non-contingent basis of a collective identity authentically rooted in the oneness of humankind? Consider first that these two features of a universal human identity can yield parameters of inclusion that are immovably all-inclusive—in other words, that are thoroughly stable and safe. In contrast, bounded and contingently grounded identities have parameters of membership that are inherently unstable. Because the boundaries of such identities are exclusionary (by definition, there are outsiders), and because they are contingent and fluid (they are socially constructed and therefore subject to reconstruction), their parameters of belonging are intrinsically susceptible to contestation, redefinition, exclusion, and othering. This threat of exclusion, of course, can come from without (i.e., othering of and by non-members). But significantly, it also comes from within. When parameters of inclusion are intrinsically bounded and contingent, the question of “who belongs?” can never be fully closed: today’s insiders can be cast as outsiders tomorrow. The instability of intergroup relations is thus augmented by the potential precariousness of in-group membership. The current discourse and political rhetoric surrounding many national identities helps illustrate this point. As the narrative of a national identity is recontested and retold, so too are its parameters of otherness redrawn: “Who counts as ‘real’ national and who doesn’t?” has become a strikingly unstable question in recent years, even in long-consolidated nations and democracies.

Thus, when parameters of inclusion are bounded and the basis of belonging contingent, the possibility of external threat is never fully eliminated and one’s claim to internal membership is never fully stable. Only a collective identity that is both genuinely non-exclusionary and non-contingently grounded—that is, an identity rooted in the genuine recognition of human oneness—can deliver a context of fundamental security: one belongs because one is human, full stop.26Identity and security are deeply intertwined concepts across a vast spectrum of disciplines and discourses, including political philosophy and contemporary public discourse. In philosophy, for instance, Charles Taylor’s influential discussion of identity and recognition emphasizes the guarantee of a secure feeling of permanence and continuity, while Avishai Margalit and Joseph Raz argue that the value to one’s identity of membership in a national group is the provision of a sense of security. In another prominent example, Nussbaum worries that the removal of local boundaries might leave “a life bereft of a certain sort of warmth and security.” The link between identity and security also finds concrete expression in many examples of contemporary politics and social unrest. The political rhetoric around “walls” and “wall building” in the United States, which was overwhelmingly articulated in relation to anxieties over collective identity and belonging, is but one recent example. The close connection between social identity and a feeling of security also has deep roots in the study of psychology. One of the key functions of a social identity, according to psychologists, is to satisfy the need for security. See: C. Taylor, “The politics of recognition,” in Multiculturalism: Examining the politics of recognition, ed. A. Gutmann, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 25-74; A. Margalit, et al, “National self-determination,” The Journal of Philosophy 87, no. 9 (1990): 439-461; M. C. Nussbaum, “Patriotism and cosmopolitanism,” Boston Review, October/November (1994); E. H. Erikson, Childhood and society, (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1950); A. Giddens, Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern Age, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991).

The distinctive characteristics of a universal human identity, therefore, reveal the possibility of a collective identity that is not only itself uniquely invulnerable to instability and destructiveness, but that is also uniquely equipped to relieve the insecurity and potential destructiveness of all other shared identities and affiliations. In other words, only a collective identity rooted in the oneness of humankind has the potential to deliver a stabilizing context of fundamental security to our particular—and otherwise unstable—group identities.

Empirical research in psychology suggests and substantiates this proposition in notable ways. Two threads of this research are briefly highlighted here. The first shows that a feeling of security (and conversely, the feeling or perception of threat) plays a critical role in constituting the context and nature of intergroup relations. Specifically, a substantial body of research finds that “felt security” relieves intergroup hostility, yielding a posture of empathy, care, and openness to out-groups,27O. Gillath, et al, “Attachment, caregiving, and volunteering: Placing volunteerism in an attachment theoretical framework,” Personal Relationships 12, no. 4 (2005): 425-446; M. Mikulincer, et al, “Attachment theory and reactions to others’ needs: Evidence that activation of the sense of attachment security promotes empathic responses,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81, no. 1 (2001): 1205-24; M. Mikulincer, et al, “Attachment theory and concern for others’ welfare: evidence that activation of the sense of secure base promotes endorsement of self-transcendence values,” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 25, no. 4 (2003): 299-312; M. Mikulincer, et al, “Attachment, caregiving, and altruism: Boosting attachment security increases compassion and helping,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89, no. 5 (2005): 817-839. while “felt threat” increases intergroup hostility and conflict.28For example: M. B. Brewer, “The importance of being we: Human nature and intergroup relations,” American Psychologist 62, no. 8 (2007): 728-738; M. B. Brewer, et al, “An evolutionary perspective on social identity: Revisiting groups,” in Evolution and social psychology, eds. M. Schaller, et al, (Madison, CT: Psychology Press, 2006), 143-161; L. Huddy, “From group identity to political cohesion and commitment,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, eds. L. Huddy, et al, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 737-773; D. R. Kinder, “Prejudice and politics,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, eds. L. Huddy, et al, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 812-851. See also: L. S. Richman, et al, “Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model,” Psychological Review 116, no. 2 (2009): 365-383; J. M. Twenge, et al, “Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92, no. 1 (2007): 56-66; W.A.Warburton, et al, “When ostracism leads to aggression: The moderating effects of control deprivation,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42, no. 2 (2006): 213-220. Thus, a sense of security is conducive to more caring and empathic relations with those who hold different bounded identities.

A second thread of evidence powerfully complements the first by suggesting that identifying with the humanity of others is associated with markedly higher levels of felt security. For example, in her analysis of in-depth interviews with Nazi supporters, bystanders, and rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust, the political psychologist Kristen Monroe found that those who conceived of themselves first and foremost as part of all humankind29K. R. Monroe, Heart of altruism: Perception of a common humanity, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996). K. R. Monroe, The hand of compassion: portraits of moral choice during the holocaust, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006). experienced distinctively higher levels of felt security.30K. R. Monroe, Ethics in an age of terror and genocide: Identity and moral choice, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012). In this study, the rescuers manifested heightened levels of ontological security, while Nazi supporters fell on the other end of the felt security spectrum. It is notable that those who identified with the whole of humankind did so in a deep and profoundly felt way. They shared, in other words, a decidedly thick universal identity. Monroe’s extensive study thus also provides evidence of the empirical possibility of an affectively rich and deeply internalized universal identity. Studies employing different methods offer consistent results. Brain imaging in neuropsychology, for example, reveals that the amygdala—a part of the brain that plays a central role in the experience of fear and aggression—becomes highly active when the average subject is shown faces from different races. But when subjects are first primed to think of people as individual human beings rather than as members of groups, the amygdala does not react.31For example: M.E. Wheeler, S. T. Fiske, et al, “Controlling racial prejudice: social-cognitive goals affect amygdala and stereotype activation,” Psychol Sci. 16, no. 1 (2005): 56-63.

These two threads of empirical research thus suggest that identifying with the oneness of humankind is associated with a greater sense of security, and that a sense of security relieves intergroup hostility and yields a posture of empathy, care, altruism, and openness toward out-groups.

Taken together, these empirical findings begin to substantiate the implications drawn logically from the inclusiveness and non-contingency of a universal source of belonging. An identity based on the essential oneness of humankind detaches bounded identities from the threat of rejection, humiliation, and domination that has forever shadowed them, and from notions of superiority and inferiority that have stubbornly fueled these threats. In other words, by transforming the overarching frame in which difference is situated and perceived—by resituating our particular identities within parameters of inclusion that are thoroughly safe, immovable, and all-inclusive—a universal identity has the potential to fundamentally relieve the seemingly inherent instabilities of our particular attachments, and to resolve the chronic tension or duality that we observed at the outset. An all-encompassing identity can thus deliver the context of genuine and enduring security that has long eluded our bounded social identities.32To be clear, nothing in this argument should be taken to suggest that bounded cultures and identities must remain static or unchanging. To the contrary, a context of deep, all-pervasive security allows our particular cultures and identities to freely change and evolve without causing the feelings of insecurity and threat that often accompany such change. See also footnotes 14 and 48.

Beyond Security: Liberating the Particular

The preceding section developed the case that an identity authentically rooted in the oneness of humankind provides a context of fundamental security, stabilizing the tensions that have long shadowed our bounded identities. The implications of a genuinely universal collective identity, however, go beyond just relieving particular identities of their destructive and destabilizing potential. What a context of deep, all-pervasive security delivers is not merely a stable equilibrium of peaceful coexistence, but rather, optimal conditions for the vibrancy and flourishing of particular identities, and of human diversity more broadly.

The idea here might be put this way: when the cost and encumbrance of insecurity and its associated protective measures are removed, on the one hand, and when an open and empathic posture toward difference becomes pervasive, on the other, then uninhibited, constructive, and creative expressions of the particular from all sides become much more probable and robust. In a context of fundamental security, goals of survival and collective self-protection can give way to more generative and constructive goals. In other words, through the felt security and certainty of belonging that an identity rooted in human oneness provides, other identities find not only protection—from their own instability and from the threat of other groups—but also liberation or release from the constraining weight that a context of latent threat has imposed on the expression of their potential. Thus, the deeply internalized consciousness of the oneness of humanity frees our bounded identities both from the threats of instability, hostility, and oppression that have stubbornly shadowed them, and from the countless safeguards and constraints that have been devised to keep these instabilities in check. Far from stifling the diversity of humankind, a reimagined universal human identity can furnish a powerful lubricant for the free expression of diversity on newly constituted terms.

Notably, the relationship between freedom and the recognition of human oneness is emphasized and elaborated in various ways throughout the Bahá’í writings. In one passage, for example, Bahá’u’lláh writes, “If the learned and worldly-wise men of this age were to allow mankind to inhale the fragrance of fellowship and love, every understanding heart would apprehend the meaning of true liberty.…”33Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, 162. In another tablet, Bahá’u’lláh explains more explicitly that “true liberty” will be achieved when identification with and love for the whole of humankind is realized in people’s consciousness.34Bahá’u’lláh, Amr va Khalq Volume 3, 472. Translations from the Persian are by the author and provisional. See also: Nader Saiedi, Logos and Civilization: Spirit, History, and Order in the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Lanham, MD: University Press of Maryland, 2000), 327-328. It is noteworthy that, in that passage, Bahá’u’lláh also characterizes the achievement of such an identity as “the ornament of utmost tranquility,” further associating universal human identity with a sense of fundamental security and freedom.

What comes into focus, then, is a radical and somewhat counterintuitive vision of human oneness that directly addresses the tension between the universal and the particular. The Baha’i writings suggest that it is by liberating the particular through the universal—by releasing, in other words, the particular from the insecurities, instabilities, and oppressive relationships that have constrained it—that a fundamental and enduring resolution emerges.35For a discussion of how this resolution compares to those that have been devised by some contemporary political theorists, see Shahrzad Sabet, “Social Identity and a Reimagined Cosmopolitanism” (paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association, 17 April 2021). Paradoxically, it is by leaning fully into a genuine and emotionally rich universalism that the particular thrives, flourishes, and fulfills its potential. Thus, and as the opening passage from the Universal House of Justice indicates, it is through the deeply felt recognition of our fundamental oneness that the infinite expressions of human diversity thrive and find their highest fulfillment.36Pursuing the logic of this argument further also illuminates the reciprocal and mutually dependent relationship between unity and diversity, and the assertion of the Universal House of Justice that “Unity, in its Bahá’í expression, contains the essential concept of diversity, distinguish ing it from uniformity.” Put briefly, a context of oneness not only facilitates the expression of the particular and the fulfilment of its distinctive potential, but the liberated expression of the particular, in turn, ensures that the emergent form of oneness is not uniformity, but rather, unity—that is, the close integration of diverse components which have transcended the narrow purpose of ensuring their own existence and found their highest fulfillment in relation to the whole.

Critiques of Universalism and the Distinctiveness of the Bahá’í View

The notions of identity and human oneness reflected in preceding sections present a significant departure from the way these concepts are frequently understood in contemporary thought and discourse, particularly in the contemporary discourses of the West. One of the most powerful and pervasive critiques of universalism—and of a collective identity rooted in the oneness of humankind, in particular—is that it poses a threat to diversity. Skeptics worry that, along a variety of dimensions (e.g., identity, language, culture, geography, institutions, etc.), the ideal of human oneness carries an inherent risk of uniformity. This homogeneity, they further worry, tends to project dominant cultures and identities, and is often propagated through (neo-)imperialistic processes.37O. Dahbour, Self-Determination without nationalism: A theory of postnational sovereignty, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012); A. Kolers, Land, conflict, and justice: A political theory of territory, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Farah Godrej, Cosmopolitan Political Thought: Method, Practice, Discipline, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). The Bahá’í writings, as we have seen, envision a radically different possibility. The concept of oneness that emerges from these writings is not uniformity, but rather, a notion of unity that “contains the essential concept of diversity.” This conception of oneness is also strikingly embodied in the practice of the Bahá’í community. Across the globe, the Bahá’í principle of the oneness of humankind is actively expressed in worldwide community-building efforts that are explicitly “outward looking”38Universal House of Justice, letter to the Conference of the Continental Boards of Counsellors, 30 December 2021.: they are, by definition, open to the full diversity of human beings, including those with other or no religious beliefs.

Another prominent critique of universalism reflects the notion that ideas rooted in our common humanity are overly abstract and disconnected from the concrete texture of everyday experience. While universalist visions might be relevant to questions of directly global or transnational concern (e.g., global governance, “global” poverty, etc.), their relevance to the relationships, neighborhoods, and communities to which people immediately belong is unclear or remote. This is especially true, the argument goes, where collective identity is concerned. In contrast to the intimacy and warmth offered by our traditional group identities, a universal human identity entails a rational commitment to the cold and distant abstraction of human oneness. From this perspective, an identity rooted in the oneness of humankind is too far removed from the texture of everyday life and experience to deliver the color, warmth, meaning, and locality that our other identities provide. A variation on this critique is the now-popularized charge of elitism: if a global, universal, or “cosmopolitan” identity works for anyone, we are told (and can vividly imagine), it works for a small, out-of-touch tribe of frequent-flying elites.39C. Calhoun, “‘Belonging’ in the cosmopolitan imaginary,” Ethnicities 3, no. 4 (2003): 531-568; M. Lerner, “Empires of reason,” Boston Review 19, no. 5 (1994); Nussbaum, “Patriotism and Cosmopolitanism.”

The Bahá’í vision of oneness and identity also diverges markedly from this view. As the preceding sections have tried to show an identity genuinely rooted in the oneness of humankind transforms the overarching context in which all identities are expressed, reorienting identities and relationships at all levels of society. From the Bahá’í perspective, then, the domain of universalism does not lie exclusively beyond borders, nor is it some distant transnational space inaccessible to the masses. Its domain, rather, is everywhere: it is concrete, immediate, and ubiquitous, encompassing all the textured communities and identities human beings value, whether they hold international passports or not. In this view, the oneness of humankind finds expression as much in the particular, and as much within the bounds of local and national communities, as it does beyond them. Again, this conception of oneness is not only reflected in the writings of the Faith, but also, strikingly, in the practice and experience of the worldwide Bahá’í community across countless cultural settings. In the Bahá’í experience, a universal identity is both directly nourished by and expressed in a range of grassroots community-building efforts that are decidedly local in nature.40For an exploration of Bahá’í community-building efforts, please see the article “Community and Collective Action,” available in the Library.

A directly related and overlapping feature of the Bahá’í conception of human oneness—and of an identity rooted in the oneness of humanity, in particular—is the radical, thoroughgoing, and unprecedented nature of the transformation it entails. Unlike some notable conceptions of universalism, the Bahá’í principle of the oneness of humankind does not simply call for the “universalization” of existing identities, norms, and institutions.41The notable conceptions of universalism referred to here are primarily those that emerge from the school of thought known as “cosmopolitanism” in contemporary Western political theory. For a thorough comparison of contemporary cosmopolitan theory to a view derived from the Bahá’í writings , see Shahrzad Sabet, “Social Identity and a Reimagined Cosmopolitanism” (paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association, 17 April 2021). For examples of contemporary Western cosmopolitan thought, see: C. R. Beitz, Political theory and international relations, second edition, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999); T. W. Pogge, Realizing Rawls, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989); D. Archibugi, The global commonwealth of citizens: Toward cosmopolitan democracy, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008); D. Held, Democracy and the global order: From the modern state to cosmopolitan governance, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995). It does not, for instance, entail the extension of existing national systems of governance and democracy to the entire globe; nor does it simply call for the expansion of existing schemes of domestic redistribution, or the replication of national collective identities in the global plane. Rather, the Bahá’í conception of the oneness of humanity represents a qualitatively distinct and transformative shift that permeates every level of society, fundamentally reorienting all identities and relationships, and transforming all structures of society. As the Universal House of Justice writes, “the principle of the oneness of humankind, as proclaimed by Bahá’u’lláh, asks not merely for cooperation among people and nations. It calls for a complete reconceptualization of the relationships that sustain society.”42Universal House of Justice, letter to the Bahá’ís of Iran, 2 March 2013. Similarly, this principle “has widespread implications which affect and remold all dimensions of human activity.”43Universal House of Justice, letter to an individual, 24 January 1994.

In other words, far from merely reflecting a linear and incremental expansion of scope from the national to global sphere, the deeply felt recognition of humanity’s oneness represents a fundamentally different and qualitatively unprecedented step in the evolution of humankind. In reference to the revolutionary changes that led to the unification of nations, for example, Shoghi Effendi writes, “Great and far-reaching as have been those changes in the past, they cannot appear, when viewed in their proper perspective, except as subsidiary adjustments preluding that transformation of unparalleled majesty … which humanity is in this age bound to undergo.”44Shoghi Effendi, World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, 45. Elsewhere, he explains that the principle of the oneness of humankind implies “a change such that the world has not yet experienced,” “a new gospel, fundamentally different from … what the world has already conceived.”45Shoghi Effendi, World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, 42-43.

The Risk of False Universalisms

Of course, any proponent of the oneness of humankind must heed a critical warning: humanity shares a long and continuing history of oppressive ideas about the “human.”46For example, see: Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World (New York: New York University Press, 2020); Walter D. Mignolo, “Who Speaks for the ‘Human’ in Human Rights?” Hispanic Issues On Line, Fall (2009): 7-24; Rinaldo Walcott, “Problem of The Human, or the Void of Relationality,” The Long Emancipation: Moving toward Black Freedom, (New York: Duke University Press, 2021), 55-58. Indeed, theorists of various kinds legitimately worry that casting our humanity in essentialist terms (i.e., taking for granted that our humanness is constituted by certain universal features, as the premise of non-contingency suggests) risks elevating a particular conception of the human over others, potentially marginalizing non-dominant experiences and opening the door to false, oppressive, and exclusionary ideas.

Adequately addressing these important concerns lies beyond the limited frame of this article. Here, I acknowledge the significance of these concerns and briefly highlight two points that might be developed in relation to them. First, recognizing that a non-contingent basis for a universal human identity exists—a recognition, it should be noted, that countless human beings readily and intuitively evince—does not require an immediate commitment to any particular, fixed, or rigid conception of our shared humanity. Of course, on a biological level, the truth that human beings constitute a single species is a basic fact that few people today deny, and which can serve as a starting point for the recognition of our shared humanity. But to arrive at a fuller and deeper common understanding of human oneness—one that can sustain a richly-conceived collective identity—a process of genuinely open, inclusive, and dynamic inquiry is required. By explicitly positing that the content or definition of a universal human identity must (minimally) include the recognition of its basis as non-exclusionary and non-contingent, we guard against false accounts of the human that violate these parameters—accounts, in other words, that exclude some human beings, or that render their humanity contingent and therefore questionable.47The validity of this point depends on the third premise described in footnote 23, namely, that human beings are able to readily recognize the humanness of another without a widely articulated consensus on the content of our humanity. Or put differently, there is, or could be, a reasonably widespread intuitive consensus about who falls within the community of human beings. This particular formulation of a collective human identity thus creates a safe and stable set of parameters within which genuine dialogue and inquiry into the content and expression of the human can take place.48It also creates a set of parameters within which particular identities and their various aspects can be examined. Not all identities—and certainly not every aspect of every identity—should be protected and empowered. The criteria of non-exclusion and non-contingency helps identify identities (or aspects of them) that cannot be reconciled with the principle of human oneness, and that must therefore be abandoned or recast.

A related point is suggested in the Bahá’í writings. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá proclaims, “[T]ruth or reality must be investigated; for reality is one, and by investigating it, all will find love and unity.”49Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, 123. In another talk, He explains:

“The first teaching [of Bahá’u’lláh] is that man should investigate reality, for reality is contrary to dogmatic interpretations and imitations of ancestral forms of belief to which all nations and peoples adhere so tenaciously … Reality is one; and when found, it will unify all mankind … Reality is the oneness or solidarity of mankind … The second teaching of Bahá’u’lláh is the principle of the oneness of the world of humanity.”50Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, 372.

Clearly, these passages assert the truth of the principle of the oneness of humankind. But by closely pairing that principle with the precept that human beings should actively investigate reality, the truth of human oneness is also rendered a testable hypothesis. Indeed, both the reality of human oneness, and ideas about the various forms and expressions it might take, are investigable propositions. The posture of free and independent investigation enjoined by the Bahá’í writings—that is, the principle that truth must be investigated free from the force of prevailing traditions, habits, and prejudices—both demands a critical interrogation of the (often oppressive) claims, structures, and relationships that bear the false imprint of universalism, and directly negates any assumption that universalism requires the imposition of a particular viewpoint or way of thought. In the Bahá’í view, a genuine recognition of the oneness of humankind can not only survive the free, open, and critical investigation of reality, but in fact, requires it. With the potential pitfalls of essentialism firmly in mind, but recognizing the transformative power that a genuine universalism could hold, the reality of human oneness might be regarded as a hypothesis that deserves the open, rigorous, and investigative posture that the Bahá’í teachings invite.51Relatedly, yet another critique of universalism claims that it threatens the diversity of thought that emerges from free and independent thinking. This critique might go as follows: the creation of national identities required, at best, a moderate manipulation of thought (through the invention and promotion of national mythologies, for example), and at worst, extreme suppressions of free and critical thinking (as in the case of totalitarian forms of nationalism). How much more of this manipulation and suppression would be needed, this critique asks, to bind the whole of humanity, with all its differences, in a collective identity? When we begin, however, from the premise that, unlike nationality, a universal identity need not be socially constructed, a different light is shed on the objection that the consciousness of human oneness depends on the curtailment of free and independent investigation. If one accepts, even as a hypothesis, that human oneness has a non-contingent basis, it follows that a genuinely free and critical investigation of reality—a commitment to truth and truth-seeking—could strengthen the possibility of a deeply internalized universal human identity, not undermine it. See also Nader Saiedi, “The Birth of the Human Being: Beyond Religious Traditionalism and Materialist Modernity,” The Journal of Bahá’í Studies 21, no. 1-4 (2011), 1-28.

A Spiritual Conception of Human Oneness and the Ongoing Learning of the Bahá’í Community

Drawing insights from the Bahá’í writings, and engaging prominent strands of contemporary thought and discourse, this article has developed the case that the solution to our collective crisis of identity lies in the genuine and deeply felt recognition of the oneness of humankind. But as the preceding section suggests, important questions remain: What might constitute the content—that is, the non-contingent basis—of a universal human collective identity? Can such an identity take shape and find expression across the vast spectrum of human diversity? And if so, how?

In this connection, the experience of the Bahá’í community and its grassroots community-building efforts present a potentially fruitful case for study. Bahá’í communities, the Universal House of Justice explains, define themselves “above all … by their commitment to the oneness of humanity.”52Universal House of Justice, letter to all who have come to honour the Herald of a new DawnOctober 2019. Significantly, for the Bahá’í community, this recognition of human oneness is a fundamental and defining feature of identity. It is a meaningful and deeply internalized commitment, entailing thick, emotionally rich bonds of genuine solidarity and love.53For a further discussion of why thick bonds of human identity might be highly hospitable to diversity, see Shahrzad Sabet, “Toward a New Universalism,” The Hedgehog Review Online, December 2020. Bahá’ís consciously strive to manifest a love that extends “without restriction to every human being”54Universal House of Justice, letter to the Bahá’ís of the United States, 22 July 2020. and to achieve “a sense of identity as members of a single human race, an identity that shapes the purpose of their lives …”55One Common Faith (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2005), 44.

As alluded to earlier, the radical vision of human oneness that motivates this identity also shapes the practice and experience of the Bahá’í community in important and potentially illuminating ways. First, the Bahá’í expression of unity contains the essential concept of diversity. Second and relatedly, the Bahá’í concept of oneness finds powerful expression in the local and the particular: it assumes a deep confluence between a universal human identity, on the one hand, and a deeply felt sense of local community and belonging, on the other. As such, the Bahá’í principle of the oneness of humankind is actively and systematically expressed in local community-building processes open to the full spectrum of human diversity56In a letter dated 1 November 2022, the Universal House of Justice urges Bahá’ís to demonstrate “that vital Bahá’í attitude of being truly outward looking, sincerely open to all, and resolutely inclusive.” and extending to every corner of the planet. Around the globe, Bahá’ís—and all who wish to join them—are consciously learning how an identity rooted in the oneness of humankind can be cultivated and expressed across a range of breathtakingly diverse communities, identities, and experiences. In light of the two core concerns raised by critics of universalism—namely, that the ideal of human oneness stifles diversity and is detached from the texture and locality of everyday life—the evolving experience of the Bahá’í community presents fertile ground for learning. Additionally, the experience of the Bahá’í community addresses the further critique that universalist projects, in particular those pertaining to social identity, are utopian and unrealizable. The breadth, depth, and wide-reaching resonance of Bahá’í endeavors should at least prompt a reconsideration of this frequently assumed limit of collective human possibility.

Another essential characteristic of the Bahá’í principle of human oneness relates more directly to the basis of a universal human identity and the question of its non-contingency. From the Bahá’í perspective, what renders a universal collective identity truly stabilizing and non-contingent—in other words, what makes it uniquely invulnerable to the tensions, instabilities, and contradictions that characterize other sources of identity—is a spiritual understanding of the human oneness on which it is based. According to the Bahá’í writings, the fundamentally spiritual reality of human beings—the human soul—is not characterized by the contingent traits that define other, bounded social identities. As the Universal House of Justice explains, “An individual’s true self is to be found in the powers of the soul, which has the capacity to know God and to reflect His attributes. The soul has no gender, no ethnicity, no race. God sees no differences among human beings except in relation to the conscious effort of each individual to purify his or her soul and to express its full powers … This truth is directly related to another—that humanity is one family.”57Universal House of Justice, letter to the Followers of Bahá’u’lláh in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1 November 2022. Also illuminating in this connection is the equation of the spiritual and with true freedom in the Bahá’í writings. Even as the spiritual is equated with the universal, the realization of true liberty is equated both with the spiritual (i.e., freedom from the material world of nature) and with genuine universalism, further reinforcing this article’s earlier discussion of liberty. On this and related points, see Saiedi, “The Birth of the Human Being.”

Recall the core argument that, in contrast to all other forms of love and association, the non-exclusionary and non-contingent basis of an identity rooted in human oneness yields a collective identity that is uniquely stable and stabilizing. In more than one passage, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá affirms this idea directly, and explicitly ties the non-contingency of universal love and identity to a spiritual source. For example:

“… fraternity, love and kindness based upon family, nativity, race or an attitude of altruism are neither sufficient nor permanent since all of them are limited, restricted and liable to change and disruption. For in the family there is discord and alienation; among sons of the same fatherland strife and internecine warfare are witnessed; between those of a given race, hostility and hatred are frequent; and even among the altruists varying aspects of opinion and lack of unselfish devotion give little promise of permanent and indestructible unity among mankind … the foundation of real brotherhood, the cause of loving co-operation and reciprocity and the source of real kindness and unselfish devotion is none other than the breaths of the Holy Spirit. Without this influence and animus it is impossible. We may be able to realize some degrees of fraternity through other motives but these are limited associations and subject to change. When human brotherhood is founded upon the Holy Spirit, it is eternal, changeless, unlimited.”58Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, 385-386.

Elsewhere, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá characterizes love for the whole of humanity as the one expression of love that is uniquely “perfect” (i.e., free from limits and instabilities) and again, ties this characteristic to the spiritual and the divine. He explains:

Love is limitless, boundless, infinite! Material things are limited, circumscribed, finite. You cannot adequately express infinite love by limited means.

The perfect love needs an unselfish instrument, absolutely freed from fetters of every kind. The love of family is limited; the tie of blood relationship is not the strongest bond. Frequently members of the same family disagree, and even hate each other.

Patriotic love is finite; the love of one’s country causing hatred of all others, is not perfect love!

Compatriots also are not free from quarrels amongst themselves.

The love of race is limited; there is some union here, but that is insufficient. Love must be free from boundaries!

To love our own race may mean hatred of all others, and even people of the same race often dislike each other.

Political love also is much bound up with hatred of one party for another; this love is very limited and uncertain.

The love of community of interest in service is likewise fluctuating; frequently competitions arise, which lead to jealousy, and at length hatred replaces love…

All these ties of love are imperfect. It is clear that limited material ties are insufficient to adequately express the universal love. The great unselfish love for humanity is bounded by none of these imperfect, semi-selfish bonds; this is the one perfect love, possible to all mankind, and can only be achieved by the power of the Divine Spirit. No worldly power can accomplish the universal love.59Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 36-37.

Spiritual forces and commitments are not only conducive to selfless association and universal love; for many human beings, they are also prime sources of meaning, purpose, and purposeful action. Casting a spiritual light on identity thus reveals a potent connection between the crisis of identity with which this article is concerned, and another pressing crisis confronting humanity, namely, our collective crisis of agency and meaning. Indeed, even as we collectively struggle to find a secure sense of identity and belonging, the yearning for a sense of meaningful agency—that is, the yearning to meaningfully shape our lives, to give purposeful expression to our potential, and to contribute constructively to the communities we inhabit—is also widely frustrated. The experience of the Bahá’í community and the conception of identity on which it is based suggest that the solution to these two crises ultimately converge. A spiritual conception of identity not only attaches an absolute sense of belonging to the condition of being human; it also provides a powerful source of purpose and agency, and a basis for meaningful, transformative action. In the Bahá’í experience, these two expressions of identity—being and doing—are deeply intertwined and often indistinguishable.

The aim of this brief section has not been to demonstrate or adequately develop these ideas. Rather, it has been to highlight how the efforts of the Bahá’í community across vastly different cultural settings might provide illuminating insights into the power and possibility of a universal collective identity and, in particular, into the potential of an explicitly spiritual conception of human oneness.

* * *

“Humanity,” the Universal House of Justice observes, “is gripped by a crisis of identity…” The Bahá’í writings proclaim that the solution to this crisis lies in a radically reconceptualized vision of human identity and oneness. Specifically, they suggest that a collective identity authentically rooted in the oneness of humankind is uniquely equipped to resolve both the tensions that have destabilized our traditional group identities, and the widely assumed tension between humanity’s oneness and its diversity. Drawing on the Bahá’í writings, and engaging prominent strands of contemporary thought and discourse, this article has developed the case that only a universal human identity can ensure the fundamental security and flourishing of our particular identities, communities, and affiliations. In this view, an identity genuinely rooted in the oneness of humankind represents a qualitatively distinct and transformative shift that permeates all levels of society, that reorients all identities and relationships, and that fundamentally protects and liberates our bounded affiliations from their otherwise inherent instabilities and contradictions. Above all, this article has tried to show that as humanity’s crisis of identity persists and intensifies, the Bahá’í vision of human oneness, and its evolving expression in the community-building efforts of the worldwide Bahá’í community, are worthy of close attention.

Human progress involves understanding and building coherence in the relationship between the seen and unseen—between what is hidden from view and what is evident right before us.

Seen and unseen realities are integral to who we are as human beings. In the Bahá’í understanding, each of us is at once a spiritual and physical being. We “approach God” through our spiritual nature, and in our physical nature we “[live] for the world alone.”1https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/abdul-baha/paris-talks/3#165303977 Our purpose and challenge in life is to understand and strive to express the spiritual dimension of our beings in how we live our temporal and physical lives. Through this coherence, we can achieve greater degrees of well-being, happiness, and accomplishment for ourselves and those around us.

Similarly, in our collective life, we need to build social realities grounded in and reflective of spiritual principles. Addressing social challenges requires applying in practical ways certain values and forces that we understand as integral to human existence. When we do this, we will support healthy, prosperous, and enduring relationships and societies. In the Bahá’í understanding:

[t]here are spiritual principles, or what some call human values, by which solutions can be found for every social problem. Any well-intentioned group can in a general sense devise practical solutions to its problems, but good intentions and practical knowledge are usually not enough. The essential merit of spiritual principle is that it not only presents a perspective which harmonizes with that which is immanent in human nature, it also induces an attitude, a dynamic, a will, an aspiration, which facilitate the discovery and implementation of practical measures. Leaders of governments and all in authority would be well served in their efforts to solve problems if they would first seek to identify the principles involved and then be guided by them.2https://www.bahai.org/documents/the-universal-house-of-justice/promise-world-peace

If human progress—as the Bahá’í teachings suggest—depends on understanding and building coherence between the invisible spiritual dimensions and the visible temporal dimensions of our reality, then it is fair to suggest that the opposite must also be true. When this relationship is not understood and reflected in our lives, when we do not see the connection between what is visible and what is invisible, human experience is marked by greater forms of hardship, lack of well-being, and patterns of social injustice. Inevitably, any effective program aimed at constructive social change must, in some way, involve making the invisible visible.

Reflecting this, for example, the Bahá’í writings speak about how addressing contemporary challenges faced by humanity requires a revitalized “consciousness” of the “oneness of humanity”3https://www.bahai.org/documents/the-universal-house-of-justice/promise-world-peace and “world citizenship.”4https://www.bahai.org/documents/the-universal-house-of-justice/promise-world-peace In becoming aware of the inextricable interconnection and interdependence of all human beings as part of one species—a reality that, in various ways, we have been veiled from seeing—constructive change can be driven. The depths of veiling of this consciousness are one of the roots of harm and conflict that justifies, for example, arbitrary and destructive distinctions between peoples along racial lines, or that paralyzes the ability to meet challenges, such as climate change, that require solutions grounded in the recognition of oneness.

This understanding—of how human progress requires making the unseen seen—provides insights into our efforts to address enduring social challenges and can help inform the ongoing development of practices and policies for change. This paper examines how these Bahá’í ideas about human progress and oneness might be applied to current discourses and efforts to address the harmful legacy of colonization of Indigenous peoples. A particular focus is on Canada, which is often viewed globally as a litmus test for progress and failure in redress and justice for Indigenous peoples. Such analysis reveals that the dynamics of the invisible being made visible at various levels has been an integral force in driving some change in Canada. Yet, at the same time, there remain fundamental realities of division and silos, as well as an enduring denial of the depths of social transformation required to address the legacy of racial inequality. From a Bahá’í perspective, if true reconciliation is to occur, current efforts and patterns must continue to be seen in a new light that can accelerate a focus on more fundamental and systemic change.

Seeing Injustice

In 2021, Canada had a moment of reckoning. The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, a First Nation in British Columbia in western Canada, announced the identification of potentially more than 200 unmarked burials of Indigenous children the Canadian state had forced to attend the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The response to the announcement set off a form of national convulsion. Many non-Indigenous Canadians appeared shocked and stunned, unaware of the reality that their country’s history included children being removed from their families for “schooling,” only to die and never return. Some in the national media called it “shocking.”5https://nationalpost.com/news/what-happens-next-after-shocking-discovery-of-215-childrens-graves-in-kamloops Political leaders called it “unimaginable.”6https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/tk-eml%C3%BAps-te-secw%C3%A9pemc-215-children-former-kamloops-indian-residential-school-1.6043778 Perhaps more than at any other moment in Canadian history, Indigenous peoples and their experiences and realities were at the foreground of Canadian public life, discourse, and debate. There was a growing chorus of calls for substantive action, change, and impromptu gatherings and memorials.

But something was puzzling in this reaction. Of course, we are appropriately horrified by acts that amount to genocide, such as those experienced by Indigenous peoples in Canada.7In recent years, the colonization of Indigenous peoples in Canada has increasingly been described as a genocide. The reporting on unmarked burials across the country since 2021 has solidified this understanding. In July 2022, Pope Francis, at the conclusion of his trip to Canada to apologize for the role of the Catholic Church in the residential school system, acknowledged that the history of assimilation and abuses amounted to genocide. But how could it be that the predominant response of Canadian governments, institutions, and organizations, as well as the general public, was surprise that such a thing could ever have occurred?

The history of Indigenous peoples8When using the term “Indigenous” in reference to Canada, it applies to three distinct peoples—First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Within each of these peoples, there is further diversity and distinction. For example, amongst First Nations, there are more than 70 language groups and 60 to 80 separate peoples. in Canada, and their enduring struggle for justice, has been thoroughly documented. The broad strokes are undeniable. At the core of European colonization was the “doctrine of discovery,” a precept from the Papacy that, if no Christians lived in a land, the lands were to be considered “discovered” and uninhabited. Simply put, the ugly root of this principle was that if there were no Christian inhabitants, then there were no human inhabitants.9https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/indigenous-title-and-the-doctrine-of-discovery Consequently, such lands were terra nullius, or empty of human beings. In the lands that now make up Canada, this racist doctrine justified a process of European settlement—and ultimately the founding of Canada in 1867—that included subjugating and displacing the diverse Indigenous peoples by imposing massive systems of oppression upon them.

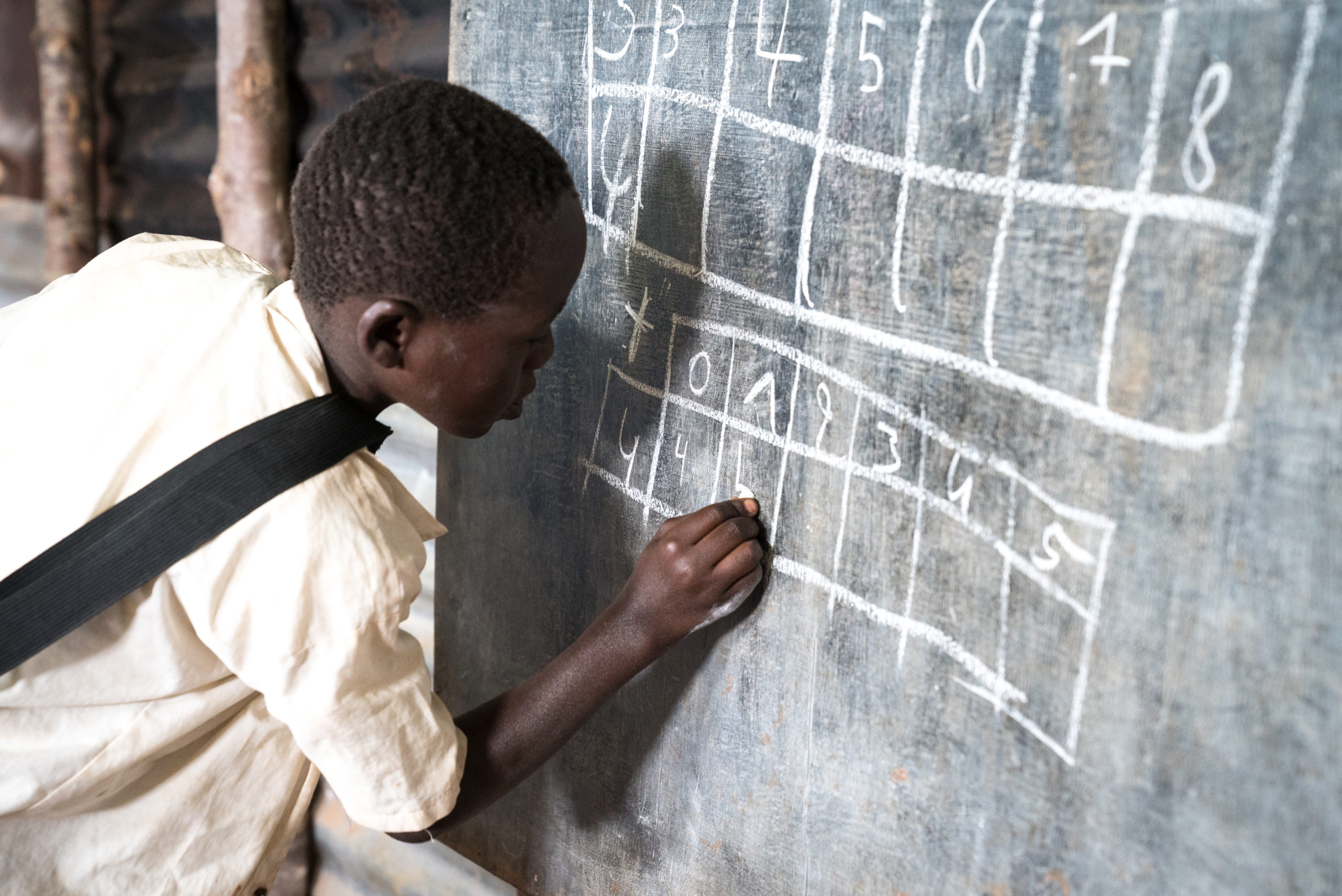

Two policy programs became the foundation of Canada. The first policy was assimilation, which aimed to destroy Indigenous knowledge, culture, spirituality, family, governance, and social systems. Sir John A. McDonald, Canada’s first prime minister, stated that there was “nothing in [Indigenous peoples’] way of life that was worth preserving” and explained the goal of the government as being “to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominions as speedily as they are fit to change.”10Session of the 6th Parliament of Dominion of Canada, 1887, quoted in “Facing History and Ourselves,” in Stolen Lives: The Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools (City: Publisher, 2018), 37. https://www.facinghistory.org/stolen-lives-indigenous-peoples-canada-and-indian-residential-schools/chapter-3/introduction Residential schools were one tool of this policy of assimilation. Their object, as explained by Hector-Louis Langevin, one of the founders of Canada and an early government leader, was as follows: “in order to educate the (‘Indian’) children properly we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that this is hard but if we want to civilize them we must do that…if you leave them in the family they may know how to read and write, but they will remain savages, whereas by separating them in the way proposed, they acquire the habits and tastes…of civilized people.”11J. Charles Boyce, ed., “Debates of the House of Commons, 5th Parliament, 1st Session: Volume 2,” Library of Parliament, 1883, https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.debates_HOC0501_02/2

The second policy program was denial and dispossession. Reflecting the “doctrine of discovery,” any claim by Indigenous peoples that they had sovereignty, ownership, or a relationship with lands and resources that made up Canada was rejected, ignored, and even outlawed. This was foundational to Canada’s economic and political creation, in addressing both the interests of different European powers—most notably the English and French—and the demands of increasing numbers of European settlers. First Nations peoples were, in various ways, forcibly removed from their lands and segregated in a system of small reserves. Even in areas where historic treaties were signed with the British Crown, both before and after Confederation, promises regarding land have been continually and systematically violated.

One of the central vehicles for implementing these assimilation and denial policies is the racist and colonial Indian Act, which passed soon after Canada was formed in the nineteenth century. The Indian Act formalized and entrenched the reserve system, authorized the removal of Indigenous children and their placement in residential schools, denied basic human rights including voting, freedom of movement, and the right to legal counsel, outlawed Indigenous forms of government, and imposed a foreign system of administrative governance through Indian Act band councils overseen and controlled by the federal government.

While some elements of the Indian Act have been amended over time, as of 2022, the Indian Act remains the primary legislation governing the lives of First Nations people in Canada.

The counterpoint to this history of colonialism has been the enduring effort led by Indigenous peoples, at times with the support of allies from many backgrounds, to address these injustices, secure recognition of Indigenous sovereignty, and establish proper relations between governments and Indigenous peoples. From Canada’s earliest days, visions of this proper relationship have been advanced in various ways. For example, in some First Nations cultures, wampum—made of white and purple seashells and beads—is woven into belts to symbolize peoples, relations, alliances, and events. The Two Row Wampum Belt of the Haudenosaunee expressed a vision of peaceful co-existence between Europeans and Indigenous peoples where “it is agreed that we will travel together, side by each, on the river of life…linked by peace, friendship, forever. We will not try to steer each other’s vessels.” As Ellen Gabriel explains:

Ka’swenh:tha or the Two Row Wampum Treaty is a significant agreement in history of the relationship between European monarchs and Indigenous peoples. Ka’swenh:tha is more than visionary. As a principled treaty it is grounded in an Indigenous intellect providing an insight and a vigilant awareness of the inevitability of the evolution of society. Ka’swenh:tha is an instrument of reconciliation for contemporary times if openness, honesty, respect, and genuine concern for present and future generations is a foundational priority.12Ellen Gabriel, “Ka’swenh:tha—the Two Row Wampum: Reconciliation through an Ancient Agreement,” in Reconciliation & the Way Forward (Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2014)

Another example is the vision of co-existence with the British that is shared by several interior First Nations in British Columbia, including the Secwepemc, Okanagan, and Nlaka’pamux. In 1910, they wrote to Prime Minister Laurier to raise the alarm about the intensifying oppression, poverty, and hardship facing their peoples. As part of their letter, they shared how their earlier leaders had envisioned proper relations:

Some of our Chiefs said, “These people wish to be partners with us in our country. We must, therefore, be the same as brothers to them and live as one family. We will share equally in everything – half and half – in land, water and timber, and so on. What is ours will be theirs and what is theirs will be ours. We will help each other to be great and good.” 13http://www.skeetchestn.ca/files/documents/Governance/memorialtosirwilfredlaurier1910.pdf

Efforts by Indigenous peoples to advance these visions of peaceful co-existence have included political actions and organization and the completion of treaties and agreements that they hoped would serve as the foundation for the manifestation of this vision. Alongside this, there has been extensive use of the courts and all forms of social movements and social action.

At the same time, Indigenous peoples have worked to maintain and pass on their culture, knowledge, and social systems to future generations, although they have often had to do this work in the shadows. Jody Wilson-Raybould, the first Indigenous person to serve as Canada’s Minister of Justice and Attorney General, shared an example of this resilience in her own family: