When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited Europe and North America between 1911 and 1913, the West was experiencing a period of great prosperity and peace. Europe had gone almost forty years without a battle on its soil, while the United States had spent nearly half a century healing the wounds of its civil war. The accelerating technological and industrial advances on both sides of the Atlantic were proudly displayed year after year at international expositions visited by citizens and rulers from all corners of the globe. The Western economies had reached unprecedented prosperity, which brought about changes in social organization. It is not surprising, then, that decades later, when describing the gestalt of public opinion in the years preceding the outbreak of World War I, a famous Austrian writer would state: “Never had Europe been stronger, richer, more beautiful, or more confident of an even better future.”1Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday (London: Cassell and Company, 1947), 152.

Such confidence in a peaceful and prosperous future was also supported by rapid changes in international politics. The peace conferences held in The Hague in 1899 and 1907 convinced many statesmen and prominent thinkers that the possibility of war was increasingly remote. For the first time, most of the world’s nations had collectively reached global agreements aimed at preventing war, perhaps the most promising of which was the establishment of an International Court of Arbitration. Experts in international law believed that, through arbitration, countries in conflict could resolve their disputes without resorting to arms or shedding a drop of blood. From 1899 until the outbreak of the Great War, hundreds of arbitration agreements were signed to secure peace between signatory countries. Even Great Britain and Germany signed an agreement in 1904.2For a list of arbitration treaties signed before 1912, see Denis P. Myers, Revised List of Arbitration Treaties (Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1912). Each of these advances was applauded by the many statesmen who were interested in internationalism as a path to peace. The Inter-Parliamentary Union, for example, which brought together more than 3,000 politicians from around the world, supported the court without reservation. Leaders such as President Theodore Roosevelt and his successor, William Taft, supported the court. Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who was president of the New York Peace Society—an organization that had invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to speak to its members—paid for the construction of the Peace Palace in The Hague. The building was inaugurated with great pomp in August 1913, just one year before the outbreak of the Great War.

The conviction that the solution to war lay primarily in international organization was so strong that the Hague Convention of 1907 agreed on the establishment of an International Court of Justice, which would not merely arbitrate but also administer justice and enforce international law. The details of such a court were postponed to a future Hague Conference, planned for the fateful year of 1915.

The academic world also gave credibility, through individuals’ works and studies, to this optimistic vision of the future. Scholars reasoned that a war between world powers would be so costly economically and so devastating militarily that the business world, the banks, the political parties, and public opinion in general would undoubtedly impose reason on any warlike temptation.

“The very development that has taken place in the mechanism of war has rendered war an impracticable operation,” wrote Ivan S. Bloch (1836–1902) in The Future of War. He added, “The dimensions of modern armaments and the organization of society have rendered its prosecution an economic impossibility.”3Ivan S. Bloch, The Future of War (Toronto: William Brigs, 1900), xi. Quoted by Sandi E. Cooper, “European Ideological Movements Behind the Two Hague Conferences (1889–1907)” (PhD. diss., New York University, 1967). This was the sixth volume of Bloch’s Budushchaya voina v tekhnicheskom, ekonomicheskom i politicheskom otnosheniyakh (St. Petersburg: Tipografiya I. A. Efrona, 1898).

Along similar lines, Norman Angell presented psychological and biological arguments in The Great Illusion (1911)—which was translated into more than twenty languages—to show that war would be an exercise in irrationality and suicide for the contending parties.

Optimism also spread to the peace movement, which was not only more influential than it is today but enjoyed far more resources and support. David Starr Jordan, who held a leading position in the World Peace Foundation and was the first president of Stanford University—and who invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to speak at Stanford—went so far as to ask in 1913, “What shall we say of the Great War of Europe, ever threatening, ever impending, and which never comes? Humanly speaking, it is impossible. … But accident aside—the Triple Entente lined up against the Triple Alliance—we shall expect no war.”4David Starr Jordan, What Shall we Say? Being Comments on War and Waste (Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1913), 18.

Andrew Carnegie, who had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá personally and received at least three letters from Him, would speak in similar terms a year before the war: “Has there ever been danger of war between Germany and ourselves, members of the same Teutonic race? Never has it been even imagined … We are all of the same Teutonic blood, and united could insure world peace.”5Andrew Carnegie, “The Baseless Fear of War,” The Advocate of Peace, April 1913, 79–80.

As in other spheres, many in the internationalist movement expressed absolute faith in arbitration as the ultimate means of ending war. “I am able to prove, and this is very essential,” said J. P. Santamaria, an Argentinian representative at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration in the same year that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at the distinguished event (1912), “that the majority of the Latin American republics have already exchanged treaties whereby armed conflicts become practically impossible.”6Report of the annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration (1912), p. 49.

“We believe not only that France, but Germany and Japan as well, would gladly join with England and the United States in treaties of arbitration which would make war forever impossible,” said another of the event’s speakers.7Address of Samuel B. Capen. Report of the annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration (1912), p. 159.

Whether as a result of faith in technological progress, hope in the positive influence of international policy aimed at peace, assurance in the power of the economy, or confidence in the supremacy of scientific reason, the prevailing visions for the future of humanity at the time of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to the West were strictly based on material criteria. The outbreak of World War I demonstrated the fallacy of that premise.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Radical Analysis of the Causes of War

The diagnosis of the world situation presented by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was very different from that of His contemporaries. Although on numerous occasions He referred to the need to establish international bodies with global reach and sufficient executive power to intervene in conflicts between countries,8For some comments and writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on this issue, see, for example: Makatib-i-Hadrat ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, vol. 4 (Tehran: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 121 B. E.), 161; Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978) 202:11 and 227:30; Paris Talks (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1967), 40:28; Promulgation of Universal Peace (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2012), 98:10 and 103:11. He also impressed on His audiences the urgent need to focus on the moral causes of war and the spiritual requirements for the establishment of peace.

Far from arguing that war was simply the result of deficient international organization, He asserted that it was also rooted in erroneous conceptions of the human being, which led irremediably towards division and contention. He especially warned of the dangers of racism and nationalism, which define the individual according to material parameters—bodily appearance and community of birth, respectively—and prioritize human beings and entire societies according to these factors, thus generating inequality and injustice, and fostering hatred and alienation, among human groups. He also referred to religious hatred, which He described as contrary not only to the foundation of religions but also to divine will.

“All prejudices, whether of religion, race, politics or nation, must be renounced, for these prejudices have caused the world’s sickness,” He said in a talk in Paris in 1911. Prejudice, He asserted, is “a grave malady which, unless arrested, is capable of causing the destruction of the whole human race. Every ruinous war, with its terrible bloodshed and misery, has been caused by one or other of these prejudices.”9‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 45:1. Ibid., p. 159.

“Man has laid the foundation of prejudice, hatred and discord with his fellowman,” He explained in 1912 in a speech at a Brooklyn church, “by considering nationalities separate in importance and races different in rights and privileges.”10‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 82:11.

“As long as these prejudices prevail, the world of humanity will not have rest,” He wrote years later.11‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 227:10. This is part of one of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s communications to the Central Organization for a Durable Peace, in The Hague.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá rejected the premises on which each of these models of thought were based. He denied, for example, the objective existence of races, stating instead that “humanity is one kind, one race and progeny, inhabiting the same globe.”12‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “Address to the International Peace Forum, New York, 12 May 1912,” Promulgation of Universal Peace, 47:6. He also denied that nations are natural realities, referring to national divisions as “imaginary lines and boundaries.”13‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 98:6. He denied any essential differences between religions, since they all have a common origin, share the same spiritual foundations, and are essentially one and the same. Furthermore, He affirmed that religious differences are due to “dogmatic interpretation and blind imitations which are at variance with the foundations established by the Prophets of God,”14‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 110:15. stressed that these aspects of religion must disappear, and even went so far as to declare that “if religion be the cause of enmity surely the lack of religion is better than its presence.”15“Abdul Baha Gives His Impressions of New York”, The Sun (New York), 7 July 1912, 8.

He spoke at a time when the ideologies characteristic of a culture of inequality (racism, nationalism, sexism, and so on) were on the rise, gradually pushing humanity into what would be the bloodiest and most catastrophic century of its history. Racism, for example, was endorsed by a significant portion of the scientific community of the time and was firmly established in large parts of the world in the form of discriminatory and segregationist laws. It was even undergoing a major transformation equipped by new “scientific” techniques—such as craniometry, phrenology, and physiognomy—that inspired new and abhorrent “social reform” initiatives, such as eugenics and racial hygiene. Nationalism, for the first time in history, had instilled in the majority of humanity the vision of a globe divided into parcels of land defined by races, cultures, and languages. It drove imperialist and colonialist policies, while colonialism, in turn, exported nationalism, imposing previously nonexistent categories and definitions on citizens and territories worldwide. At the same time, longstanding religious conflicts were still very much present, reviving old grievances and warlike moods—as exemplified by the chronic problems in the Balkans, which were in full swing when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited the West.

Even individuals and organizations with noble goals held such doctrines of inequality. Many pacifists, for example, saw war not so much as a moral problem, but as a biological one. Influenced by racism and social Darwinism, they based their criticism of war on the argument that “fit” men were sent to the battlefield, where they died, while “unfit” men stayed behind and reproduced. The consequence of such a phenomenon, they believed, was “racial weakening.”

“Only the man who survives is followed by his kind,” wrote the aforementioned David Starr Jordan. “The man who is left determines the future. From him springs the ‘human harvest’ …”16David Starr Jordan, War’s Aftermath (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), xv.

Along the same lines, Norman Angell also criticized colonial expansion in biological terms, arguing that domination and contact between civilizations prolonged the life of “weak races.”

“When we ‘overcome’ the servile races,” Angell reasoned in his internationally best-selling book, “far from eliminating them, we give them added chances of life by introducing order, etc., so that the lower human quality tends to be perpetuated by conquest by the higher. If ever it happens that the Asiatic races challenge the white in the industrial or military field, it will be in large part thanks to the work of race conservation, which has been the result of England’s conquest …”17Norman Angell, The great illusion (London: William Heinemann, 1910), 189. In 1933 Angell would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Benjamin Trueblood, secretary of the American Peace Society, who met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Washington, D.C., raised the possibility of a future world federation as a consequence of a “great racial federation” in the Anglo-Saxon world.18Benjamin Trueblood, The Federation of the World (Boston: The Riverside Press, 1899), 132. This idea was similar to that put forward by Andrew Carnegie.

In this context, we can understand—with the perspective provided by the passage of more than a century since His travels—that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s warnings about the causes of war could not be understood by societies immersed in paradigms of thought totally different from the ones He presented.

And just as the meanings and diagnoses of the causes of war differed between those provided by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the dominant discourses of the time, so did proposals for the establishment of peace. As explained, the international community had placed its hope in legislation and international institutions as mechanisms for ensuring peace; some pacifists sincerely believed that such changes also required the racial hegemony of certain peoples. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, however, emphasized a completely different concept: peacemaking would only be possible when humanity reached the understanding that it is one and acted in accordance with this principle. He brought this idea forward in a great number of His talks. For instance, in Minneapolis, He stated that human beings “must admit and acknowledge the oneness of the world of humanity. By this means the attainment of true fellowship among mankind is assured, and the alienation of races and individuals is prevented … In proportion to the acknowledgment of the oneness and solidarity of mankind, fellowship is possible, misunderstandings will be removed and reality become apparent.”19‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 105:6.

By making such a statement, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá presented His listeners with a radical challenge. The recognition of the oneness of the human race implies, on one hand, the acceptance that there is a primordial identity common to all human beings, which goes beyond any physical or accidental diversity between individuals. It also implies the abandonment of any vision of the human being—foundational to beliefs such as racism, sexism, unbridled nationalism, and religious exclusivism—that justifies human inequality. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approach, therefore, clashed head-on with the discourses of the time and the materialistic premises that underpinned them.

The Great War

Although ‘Abdu’l-Bahá praised on numerous occasions progress that humanity was experiencing, for example in economics, politics, science, and industry, He also warned that material progress alone would not be capable of bringing true prosperity without a commensurate spiritual advancement.

“Material civilization concerns the world of matter or bodies,” He explained during His visit to Sacramento, “but divine civilization is the realm of ethics and moralities. Until the moral degree of the nations is advanced and human virtues attain a lofty level, happiness for mankind is impossible.”20‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 113:15.

From this perspective, the ideologies of inequality that permeated all areas of human endeavor were totally incapable of promoting lasting peace, including in movements that promoted pacifism, internationalism, and diplomacy.

“The Most Great Peace cannot be assured through racial force and effort,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained in an address in Pittsburgh:

It cannot be established by patriotic devotion and sacrifice; for nations differ widely and local patriotism has limitations. Furthermore, it is evident that political power and diplomatic ability are not conducive to universal agreement, for the interests of governments are varied and selfish; nor will international harmony and reconciliation be an outcome of human opinions concentrated upon it, for opinions are faulty and intrinsically diverse. Universal peace is an impossibility through human and material agencies; it must be through spiritual power …

For example, consider the material progress of man in the last decade. Schools and colleges, hospitals, philanthropic institutions, scientific academies and temples of philosophy have been founded, but hand in hand with these evidences of development, the invention and production of means and weapons for human destruction have correspondingly increased …

If the moral precepts and foundations of divine civilization become united with the material advancement of man, there is no doubt that the happiness of the human world will be attained and that from every direction the glad tidings of peace upon earth will be announced.21‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 44:13–15.

Based on this premise, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá challenged a falsely optimistic vision of the world, noting that, if the moral and spiritual dimensions of social reality were also assessed, it would become apparent that the world was experiencing a moment of great decadence. “If the world should remain as it is today,” He said in Chicago in 1912, “great danger will face it.”22‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 104:1.

“Observe how darkness has overspread the world,” he explained in Denver:

In every corner of the earth there is strife, discord and warfare of some kind. Mankind is submerged in the sea of materialism and occupied with the affairs of this world. They have no thought beyond earthly possessions and manifest no desire save the passions of this fleeting, mortal existence. Their utmost purpose is the attainment of material livelihood, physical comforts and worldly enjoyments such as constitute the happiness of the animal world rather than the world of man.23‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 107:4.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá warned of the acute risk of an impending international conflict on no less than seventeen occasions. “Europe itself,” He said in Paris in 1911, “has become like one immense arsenal, full of explosives, and may God prevent its ignition—for, should this happen, the whole world would be involved.”24“Apostle of Peace Here Predicts an Appalling War in the Old World,” The Montreal Daily Star, 31 August 1912, 1. [The following includes numerous incomplete citations—most need page or publisher data] For other comments about the possibility of a war, see Promulgation of Universal Peace, 3:7, 103:11, 108:1, 114:2; ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on Divine Philosophy (Boston: The Tudor Press, 1918), 95. “The Awakening of Older Nations,” The Advertiser (Montgomery, Alabama), 7 May 1911; “Turks Prisoner for 40 Years,” The Daily Chronicle (London), Western Edition, 17 January 1913, 1; “Abdul Baha’s Word to Canada,” Toronto Weekly Star, 11 September 1912; Montreal Daily Star, 11 September 1912, 2; “Abdul Baha’s Word to Canada,” Montreal Daily Star, 11 September 1912, 12; “Persian Peace Apostle Predicts War in Europe,” Buffalo Courier, 11 September 1912, 7; “Message of Love Conveyed by Baha,” Buffalo Enquirer, 11 September 1912, 5; “Urges America to Spread Peace,” Buffalo Commercial, 11 September 1912, 14; “Abdul Baha an Optimist,” Buffalo Express, 11 September 1912, 1; “Bahian Prophet Returns After a Trip to Coast,” Denver Post, 29 October 1912, 7.

Despite this and other explicit warnings, His audiences remained for the most part unmoved. Confidence in material well-being weighed more heavily on public opinion than His diagnosis of the moral state of the world.25‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 34:5.

He reiterated his warnings in the years between the end of World War I and His passing in 1921. In His correspondence, He explained that a second world conflagration was imminent, despite the terror caused by the first world war and the enormous progress that had been made in international governance with the establishment of the League of Nations.

“Although the representatives of various governments are assembled in Paris in order to lay the foundations of Universal Peace and thus bestow rest and comfort upon the world of humanity,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote in 1919, “yet misunderstanding among some individuals is still predominant and self-interest still prevails. In such an atmosphere, Universal Peace will not be practicable, nay rather, fresh difficulties will arise.”26‘Abdu’l-Bahá, tablet to David Buchanan of Portland, Oregon, Star of the West, 28 April 1919, 42.

“For in the future another war, fiercer than the last, will assuredly break out,” He wrote in 1920. “Verily, of this there is no doubt whatever.”27Letter to Ahmad Yazdaní, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 228:2.

In another letter sent the same year, He was even more explicit. After presenting—as He had done in His addresses in the West—some of the spiritual requirements for the establishment of peace, He closed by enumerating some of the elements that would eventually lead humanity to World War II just nineteen years later:

The Balkans will remain discontented. Its restlessness will increase. The vanquished Powers will continue to agitate. They will resort to every measure that may rekindle the flame of war. Movements, newly born and worldwide in their range, will exert their utmost effort for the advancement of their designs. The Movement of the Left will acquire great importance. Its influence will spread.28Letter sent through Martha Root, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 202:14.

The Birth of a New Society

No reader of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá should be tempted to think that, in His exposition of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, He moved only within the theoretical realm. On the contrary, while His efforts to spread Bahá’u’lláh’s message were enormous, His endeavors to bring those teachings into the realm of action were colossal. In a conversation in London, for example, referring to one of the many congresses held at the time, bringing together philanthropists eager to improve the world, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stressed, “To know that it is possible to reach a state of perfection, is good; to march forward on the path is better. We know that to help the poor and to be merciful is good and pleases God, but knowledge alone does not feed the starving man …”29‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982)60.

Throughout His ministry, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá directed the Bahá’í community to make itself a model of the future society foretold by Bahá’u’lláh—one through which humanity might witness the transformations that accompany the application of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings to social and interpersonal relations.

In several of His talks, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described the Bahá’ís of Persia (now Iran) as one such example. They lived in an environment in which religious segregation was a social reality. Zoroastrians, Jews, Christians, and other religious minorities lived in isolation from their Muslim neighbors and also separated from each other. Being considered impure beings (najis), the minority groups were subject to strict rules that regulated not only their relations with Muslims, but also the jobs they performed and even the clothes they wore. In this environment, bringing people from different religious backgrounds together in the same room was not just taboo, but unthinkable. Despite this, the Bahá’í community in Persia managed to become—first under the guidance of Bahá’u’lláh and then of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá—a cohesive group comprising people from all religious backgrounds. Having in common their faith in the transformative capacity of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, they were able to set aside prejudices inherited from the surrounding society and their ancestors and work together to improve conditions for their fellow citizens. It was not long before Persian Bahá’ís—men and women alike—learned to make decisions collectively and to implement them without regard for different backgrounds or genders.

Such a change not only resulted in the unprecedented growth of the Bahá’í community, but also in the proliferation of numerous social and charitable projects throughout the country. For example, during the ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the Persian Bahá’ís managed to establish no less than twenty-five schools, including some of the country’s first schools for girls. Beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century, Bahá’ís in Persia also established health centers in several cities, including the Sahhat Hospital in Tehran, which followed the instructions of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to include in its mission statement that it would provide “service to mankind, regardless of race, religion and nationality,” a revolutionary statement at that time and place.30Seena B. Fazel and Minou Foadi. “Baha’i health initiatives in Iran: a preliminary survey,” The Baha’is of Iran, eds. Dominic P. Brookshaw and Seena B. Fazel (New York: Routledge, 2008), 128.

While this was happening in the East, American Bahá’ís were working under the leadership of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to racially integrate their community.

“Strive with heart and soul in order to bring about union and harmony among the white and the black and prove thereby the unity of the Bahá’í world wherein distinction of color findeth no place, but where hearts only are considered,” He wrote in one of His letters to them. “Variations of color, of land and of race are of no importance in the Bahá’í Faith; on the contrary, Bahá’í unity overcometh them all and doeth away with all these fancies and imaginations.”31Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 75.

He also exhorted them to “endeavor that the black and the white may gather in one meeting place, and with the utmost love, fraternally associate with each other.”32Bonnie J. Taylor and National Race Unity Conference, eds., The Power of Unity (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1986), 30.

“If it be possible,” He wrote on another occasion, “gather together these two races—black and white—into one Assembly, and create such a love in the hearts that they shall not only unite, but blend into one reality. Know thou of a certainty that as a result differences and disputes between black and white will be totally abolished.”33The Power of Unity, 28.

The process by which the Bahá’í community in the United States became a model of racial integration was accelerated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to North America—through His personal example, His participation in integrated meetings, His encouragement to Bahá’ís who held them, and His constant instructions in all the cities He visited on the issue of race.

After the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá commissioned Agnes Parsons, a Bahá’í and member of high society in Washington, D.C., to organize the first Race Amity Conference, which took place in May 1921. The event, promoting racial unity and harmony, triggered a national movement that replicated the Conference in different parts of the United States in the following years, involving not only the American Bahá’í community, but also many other organizations and societal leaders. The result of these efforts was the transformation of the Bahá’í community into a group actively engaged in banishing the racial prejudices so present in its surrounding society.

In His efforts to demonstrate, through the global Bahá’í community, empirical proof that unity and freedom from prejudice leads to peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also promoted collaborative ties between the Bahá’ís of the West and the East. Beginning in the early twentieth century, He encouraged Persian Bahá’ís to travel to Europe and North America, and Western Bahá’ís to visit Persia or India. He promoted communications between Bahá’í communities. For example, the Star of the West, the journal of the Bahá’ís of the United States, included a section in Persian and was regularly sent to Persia. As development projects in Persia grew and became more complex, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged Western Bahá’ís to support them and extend assistance. As a result, in 1909, Susan Moody, M.D., moved to the country to work at the Sahhat hospital in Tehran. Moody was followed by other Bahá’ís, including teacher and school administrator Lilian Kappes, nurse Elizabeth Stewart, and fellow doctor Sarah Clock. In 1910, the Orient-Occident Unity was founded with the aim of establishing collaboration in different fields between the people of Persia and the United States.34This name was adopted in 1912. Its earliest name was the Persian-American Educational Society. The work of this organization involved not only many Bahá’ís, but other prominent organizations and individuals.

All these transformations provided glimpses of the social implications of the principles promulgated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and presented examples of the effects generated by applying in the field of action the principle of world unity and the conception of the human being enunciated by Bahá’u’lláh.

Addressing the immediate needs

On 24 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austrian-Hungarian Empire, was assassinated in Sarajevo. A few weeks later, the European powers were at war, and the disaster predicted by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá only a few years earlier became a reality.

The Ottoman regions of Syria and Palestine did not escape the dire consequences of the conflagration. The area was hit by famine caused by pillaging Ottoman troops as they crossed the territory to reach Egypt, where they were defending the strategic Suez channel. In the Haifa area, circumstances were particularly complicated. The local population held diverging alliances. The Arabs were divided between those sympathizing with the French and those supporting the Ottoman Empire, while the members of the large German colony supported their own country. These divisions caused tension and sometimes produced violence. The city was also the target of bombings from the sea. Thus, within a few weeks, Haifa and its surroundings experienced a rapid transition from a relative state of peace to severe insecurity associated with a humanitarian crisis. The conflict caused acute needs that required urgent attention.

Before the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had taken steps that would allow Him to ameliorate these conditions. His most visible contribution was to provide food for the people of Haifa and its vicinity. At the beginning of the twentieth century, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had established various agricultural communities around the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan Valley, with the most important one in ‘Adasiyyih, in present-day Jordan. During the hardest years of the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent shipments of foodstuffs from this location to Haifa, using some two hundred camels for just one trip, which gives an idea of the scale of the aid.35For more information on this, see Iraj Poostchi, “Adasiyyah: A Study in Agriculture and Rural Development,” Bahá’í Studies Review 16 (2010), 61–105. To distribute the food within the population, He organized a sophisticated rationing system using vouchers and receipts to ensure that the food reached all those in need while preventing abuse.

“He was ever ready to help the distressed and the needy,” a witness was quoted as saying in 1919 in London’s Christian Commonwealth:

… often He would deprive himself and his own family of the necessities of life, that the hungry might be fed and the naked be clothed. … For three years he spent months in Tiberias and Adassayah, supervising extensive works of agriculture, and procuring wheat, corn and other food stuffs for our maintenance, and to distribute among the starving Mohamedan and Christian families. Were it not for his pre-vision and ceaseless activity none of us would have survived. For two years all the harvests were eaten by armies of locusts. At times like dark clouds they covered the sky for hours. This, coupled with the unprecedented extortions and looting of the Turkish officials and the extensive buying of foodstuffs by the Germans to be shipped to the “Fatherland” in a time of scarcity, brought famine. In Lebanon alone more than 100.000 people died from starvation.36“News of Abdul Baha,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 22 January 1919, 196. Text in Amín Egea, The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2 (Oxford: George Ronald, 2018), 427–428.

“Abdul Baha is a great consolation and help to all these poor, frightened, helpless people,” another report read.37“Bahai News,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 3 March 1915, 283. Text in The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2, 410.

A few years later—just after the war—a British army officer described ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s role in reuniting the divided peoples of Haifa, saying, “Many are looking to him to solve the problems arising between Moslem and Christian sects.”38W. Tudor Pole, quoted in “Palestine of Tomorrow,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 24 September 1919, 614. Text in The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2, 426.

Reading Reality in Times of Crisis

The three levels of action taken by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on the issue of war—participation in the discourses of His time, building a community based on spiritual principles, and paying attention to the immediate needs arising from the outbreak of war—offer us an opportunity to reflect, nearly one hundred years after His passing, on the appropriateness of the models of thought that currently influence global decision-making.

Today, as then, the world is beset by a large number of threats. The progressive environmental decline, the deficient global economic system—which allows for the existence of extremes of wealth and poverty and, at the same time, periodically causes major economic crises—the prevalence of war in a multitude of forms and its constant threat in a context of unprecedented technological development, the rapid spread and assimilation of hate mongering of all kinds and of all orientations, and the rise of an unfettered nationalism with an associated drive against human diversity and resistance to the processes of global convergence, are just some of the challenges facing humanity. In addition to these, which have been created by human beings themselves, there are others of an unexpected and natural character which, like the current global pandemic, highlight the fragility of a human ecosystem that has been greatly weakened by internal divisions and inequalities.

If the response to these crises—some of them unprecedented—is to be based on contradictions similar to those of the internationalists or pacifists of the years before the Great War, we can anticipate that any remedy applied will be dramatically limited in its influence. Can, for instance, a humanity that still clings to a nationalistic world view provide an adequate response to global problems? Is it possible for societies that perceive consumerism and the accumulation of goods as a path to true happiness to find solutions to crises such as global warming?

If we heed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s advice, the diagnosis of these and future crises should not depend solely on an analysis of the material circumstances that converge in each of them, but should also address the ultimate, moral causes of these phenomena. Some of these include the pursuit of self-interest, submission to materialism, the perception that struggle and strife are legitimate means of resolving conflicts, the persistence of prejudices that deny human equality, and the distortion of the purpose of religion. As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá consistently stated in His talks and writings, the solutions to the problems that afflict the human race depend not only on a change in the material conditions of humanity but also on a transformation in our understanding of what it means to be human, of our existential purpose, and of the moral framework upon which we base our actions.

In the late summer of 1911 in the United States, Albert Smiley found a letter sent from Egypt among the items in his mail. Dated August 9, it was from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, head of a religion which Smiley had only briefly encountered the year before.1Two Bahá’ís had attended the 1911 Lake Mohonk Conference and another Bahá’í met Albert Smiley at a different conference in 1911, which may in part explain how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was aware of the annual Lake Mohonk Conferences. Egea, Amin, The Apostle of Peace: A Survey of References to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the Western Press 1871-1921, Volume One: 1871 – 1912, p. 635, note 12. The letter addressed Smiley as the founder and host of the Lake Mohonk Conferences on International Arbitration and praised those gatherings and their goal of establishing arbitration as the means to settle disputes between nations. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated emphatically, “What cause is greater than this!” Explaining how His Father, Bahá’u’lláh, had advocated the unity of the nations and religions, He asserted that the basis of this unity was the oneness of humanity.2“Tablets from Abdul-Baha,” Star of the West, Vol. II, No. 15, December 12, 1911, pp. 3-4. To ensure that His message to the sponsors was received and considered, a second letter was sent on August 22 to the Conference secretary, Mr. C. C. Philips. It began, “The Conference on International Arbitration and Peace is the greatest results [sic] of this great age.”3“Tablets from Abdul-Baha,” Star of the West, Vol. II, No. 15, December 12, 1911, p. 4. In response, the organizers invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to take part in the 1912 Conference and to address one of its sessions.4Egea, Amin, The Apostle of Peace: A Survey of References to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in the Western Press 1871-1921, Volume One: 1871 – 1912, p. 302

Even though other groups in the United States and Europe were holding meetings to promote peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá singled out the Lake Mohonk Conferences; for this reason, these exceptional gatherings are worthy of close examination. At them, Albert Smiley and his identical twin brother, Alfred, created an atmosphere that not only illuminated the issue under discussion but resulted in practical action.

The devoutly religious, idealistic Smiley brothers were lifelong members of the Society of Friends, the Christian Protestant denomination better known as Quakers. In their youth, they worked as educators. Then, in 1869, they pursued a different direction by purchasing a dilapidated hunting lodge on the shore of Lake Mohonk in the Catskill Mountains, half a day’s travel by train from New York City, and they successfully developed it into a fashionable resort.

Albert gained a reputation for civic-mindedness and, out of a desire to ameliorate the ills of society, developed a keen interest in social movements. Consequently, Rutherford Hayes, then President of the United States, appointed him to the federal Board of Indian Commissioners. In the course of this service, Smiley recognized an urgent need to create a space where issues regarding America’s indigenous peoples could be explored, and solutions proposed and acted upon. To that end, in 1883, he invited his fellow commissioners and others working on behalf of indigenous populations to his resort for a conference, which proved useful enough to be held annually until 1916. The consultation which occurred during those sessions influenced the course of government policy. Pleased with the success of the Smiley efforts, President Hayes suggested that the brothers establish a similar conference focused on addressing injustices faced by Americans of African descent. The Smileys organized and hosted the first national conference on the situation of Black Americans in 1890, but the extraordinary challenge posed by the issue forced them, with great reluctance, to abandon the conference after just two years.5Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, pp. 30-45.

Unlike many of their fellow Quakers, the Smileys were not strict pacifists; however, their religious upbringing had instilled in them an unshakeable reverence for life.6Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, , p. 5. They were wholeheartedly committed to the cause of peace. Drawing upon what they had learned from experience, in 1895 they established the Conferences on Arbitration at Lake Mohonk. During that first gathering, a standing international court of arbitration was proposed and discussed at length. Among the participants was the man who would serve as head of the US delegation to the conference at the Hague a few years later when the Permanent Court of International Arbitration was established. The exploration of the ins and outs of such a court at Lake Mohonk informed the thinking of many of the participants, especially the American delegation.7Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, pp. 62-63. This would be the first tangible fruit of the arbitration conferences.

Managing two annual conferences, Albert Smiley developed a set of working principles. First, the topic had to be one that could lead to action. One reason the conferences on indigenous populations were influential was that all policy regarding the indigenous peoples in the United States was set by one national government agency, so a handful of officials could implement the recommendations that were made. In contrast, most of the laws and policies that affected the situation of African Americans were set and executed by countless state and local level governments.8Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, p. 40. The issue of international arbitration, while global in scope, shared more in common with the first example because a small number of highly placed politicians, officials, and diplomats determined policy. This meant that the number of people requiring educating and persuading was manageable.

Smiley’s second underlying principle was that religion had a major role to play in resolving social problems, including the promotion of world peace. Religious leaders were invited to take part in all the conferences. The meetings themselves had a religious overtone and the participants were expected to adhere to the Quaker moral code, which included an unwritten prohibition against drinking alcoholic beverages and playing cards.9Davis, Calvin C., “Albert Keith Smiley”, Harold Josephson, editor, Biographical Dictionary of Modern Peace Leaders, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1985, p. 889.

The Smileys also learned how to conduct consultation effectively. A variety of points of view were welcome and fostered, and Albert chose chairmen who would not use their role to promote their own viewpoints or agendas and would be even-handed. The Smileys ensured that no group or position dominated the discussion portions of the sessions. Discussion was to be conducted at the level of principle rather than based upon specific matters, especially those that were controversial, such as the Spanish American War. The Smileys did not allow speakers at the arbitration conference to give talks about the horrors of war, lest the consultation become less about solutions and more about sentiment. The conferences were, however, an opportunity to provide information about legislation, treaties, and other news related to the topic at hand.

At the outset, idealistic leaders of social movements whose worldviews were not always practical filled the arbitration sessions, so the Smileys began to invite representatives of the business community. Nothing was worse for the average businessman than the economic disruption and uncertainty of a war. Women were always invited and fully participated, which was liberal for the time.

Finally, Albert Smiley recognized that the conference schedule must allow time for informal meetings and the networking that naturally occurs through socializing. The plenary sessions only lasted two hours in the morning and two hours in the evening, with the rest of the day unscheduled except for meals. The expansive property, much of which was woodlands with hiking trails surrounding the lake, provided welcome opportunities both to meditate in nature and to discuss ideas privately.10For a lengthy discussion of how the conferences were conducted, see Burgess, pp. 61-67.

By the time ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote to the organizers of the conferences, the gatherings had become influential. The groundwork necessary for the establishment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague, for instance, was established there, and the American Society of International Law was also created at the conference, in the 1905 session.11For a brief discussion of the fruits of the Lake Mohonk Arbitration Conferences see Burgess, p. 890.

Establishing the Court of Arbitration was only the beginning, for as that institution undertook its work, other issues arose: How could countries be encouraged or required to bring matters to the Court rather than resort to war? How were the decisions of the Court to be upheld? Treaties became an obvious instrument and topic for discussion. Because the conferences were held annually with many of the same participants, different layers of the matter of arbitration were explored over their 21-year history.

When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed the conference as its opening speaker on the evening session on May 15, 1912, He was introduced by the conference chairman, Nicholas Murray Butler, President of Columbia University, who would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Among the approximately 200 people in attendance were the future Prime Minister of Canada, W. MacKenzie King, ambassadors, jurists, journalists, academics, religious leaders, businessmen, trade unionists, and leaders of civic organizations, including peace activists. The speakers who followed Abdu’l-Bahá that evening came from Nicaragua, Argentina, Germany, and Canada—a sampling of the many countries represented.12Report of the Eighteenth Annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, Published by the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, 1919, pp. 42 – 63.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá was allotted twenty minutes for His talk, most of which was in the form of reading a previously submitted English translation. His address began with a discussion of Bahá’u’lláh’s emphasis on the oneness of humanity and His promise of the coming of the “Most Great Peace.” He explained to the audience that Bahá’u’lláh promulgated His Teachings during the nineteenth century when wars were raging throughout the world among religious sects, ethnic groups, and nations. His Father’s teachings, explained ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, inspired many people to put aside their prejudices and instead love and closely associate with their former enemies. The talk then turned to the importance of investigating reality and forsaking blind imitation; for, as He pointed out, once people see truth clearly, they will behold that the foundation of the world of being is one, not multiple. Following His discussion of the oneness of humankind, He explored the agreement of science and religion. Throughout the speech, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stressed that religion should bring about a bond uniting the peoples of the world, not be the cause of disunity; that all forms of prejudice must be abolished, including racial, religious, national, and political; and that women should be accorded equal status with men. He then briefly touched upon the problem of the disparities of wealth and poverty. Finally, He stated that philosophy is incapable of bringing about the absolute happiness of mankind: “You cannot make the susceptibilities of all humanity one except through the common channel of the Holy Spirit.”13Report of the Eighteenth Annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, Published by the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration, 1919, pp. 42 – 44.

The members of His entourage recorded that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talk was well-received and that many people approached Him afterward to thank Him and to speak with Him.14Mahmud’s Diary, p. 101. Note that the chronicler, Mahmud, was confused about the dates. The full translation of His talk was included in the widely distributed report of the conference and much of the press coverage also mentioned it.15The conference published an annual report which was sent to all libraries across the United States with more than a 10,000 book collection (the average size of a small community or branch library). Burgess, p. 65. One of the promoters of the conferences was the wealthy industrialist, Andrew Carnegie, who establishing public libraries across the United States as well as for the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. (There are indications that Carnegie was present when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at Lake Mohonk, but that is unconfirmed.) For a thorough accounting of the press coverage of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s participation in the 1912 conference, see Egea, pp. 306. Press accounts of His arrival in the United States also frequently made mention of His intention to participate in the Lake Mohonk Conference. Ibid, pp. 197, 198, 201, 203, 217, 286, 298, 299.

Earlier that day, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had taken advantage of the unscheduled afternoon to give at least one informal talk and to speak with a number of the conference participants. He did not stay for the entire event but returned to New York the following morning after spending His last hours at the resort visiting with Albert Smiley.16Mahmud’s Diary, pp. 102 – 103.

The 1912 conference was the last one attended by the far-sighted Albert Smiley. Alfred had already passed away and Albert followed his twin in December of that year. Their brother, Daniel, whose attention to detail in planning the conferences was part of their success,17Larry E. Burgess, The Smileys: A Commemorative Edition, Moore Historical Foundation, Redlands, California, 1991, p. continued to host the conferences until circumstances forced him to discontinue them when the United States entered WWI in 1917. Years later, Dr. Butler, reviewing his own participation in the conferences between 1907 and 1912, reflected, “it is extraordinary how much vision was there made evident.” However, he concluded, “it is more than pathetic that that vision is still waiting for fulfilment.”18Butler, Nicholas Murray, Across the Busy Years: Recollections and Reflections II, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1940, p. 90.

All the efforts of peace organizations and gatherings such as the Lake Mohonk Conferences culminated in the creation of the League of Nations at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. However, although President Woodrow Wilson was given credit for conceiving the League, the US Congress refused to ratify the treaty that would make the United States a member. Thus, despite hopeful expectations, the League was born handicapped and, after a few initial achievements, proved to be ineffective at preventing wars. It was, nevertheless, a beginning.

Following the Great War, the United States returned to its default foreign policy position of isolationism; namely, the conviction that the country should stay out of the conflicts afflicting other parts of the world. It was as if all the work done before the war to promote world peace through internationalism had been undone. This situation was exacerbated by the 1919 “Red Scare,” during which anarchists and communists were accused of instigating several violent incidents. Moreover, in the 1920s, deep-seated prejudices took firmer hold of US public policy. Congress passed restrictive immigration legislation in 1924 to keep out Jews and Catholics. It became all but impossible for Africans to legally immigrate, and Chinese immigration was banned by law.

Meanwhile, in 1919, white people attacked and set fire to black neighborhoods in Chicago and, in 1921, attacked and even bombed from the air a prosperous black district in Tulsa, Oklahoma, leaving untold black citizens dead and the lives of the survivors ruined. The white supremacist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic organization, the Ku Klux Klan, experienced a resurgence, demonstrating its strength with a large parade through Washington, D.C. in 1926, its members’ distinctive white-hooded uniforms blending with the backdrop of the gleaming white marble of the U.S. Capitol building.

On the international front, fascism and communism arose quickly from the still-smoldering ashes of Europe. The armistice of 1918 would prove to be only an intermission before war erupted again in the 1930s. In the Far East, Japan’s armies were on the move, beginning with the 1931 invasion of the Manchurian region of China. In country after country, rearmament accelerated. If ever the peoples of the world needed to grasp Bahá’u’lláh’s message that humankind is one, it was during the period between the World Wars.

World peace remained the primary focus of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s talks when He visited California a few months after His appearance at the Lake Mohonk Conference. In a talk given at the Hotel Sacramento on 26 October 1912, He said that “the greatest need in the world today is international peace,” and after discussing why California was well-suited to lead the efforts for the promotion of peace, He exhorted attendees: “May the first flag of international peace be upraised in this state.”

One of those inspired by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision of California as a leader in the promotion of world peace was Leroy Ioas, a twenty-six-year-old resident of San Francisco and rising railway executive. He remembered how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had met with many prominent people during His ten months in the United States and, drawing upon His example, some years later Ioas became determined that Bahá’í principles should be widely promulgated among community leaders, especially those in positions to put them into effect or to influence the thinking of the citizenry. In 1922, Ioas wrote to Agnes Parsons in Washington, DC, to solicit her opinion and guidance about the prospect of a unity conference in his city. The previous year, at the express request of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, she had organized a successful, well-attended Race Amity Conference in her own racially polarized region of the South. Ioas noted in his letter that the challenge on the West Coast was not simply prejudice towards black people, for their numbers were few, but strong animosity towards the more numerous Chinese and Japanese citizens. Parsons responded with encouragement and suggestions. Armed with this guidance, Ioas approached two of the pillars of the Bay Area Bahá’í community—Ella Goodall Cooper and Kathryn Frankland—to gain their support for a conference. With this groundwork laid, he proposed a unity conference to the governing council for the San Francisco Bahá’í community, which decided it was not timely.

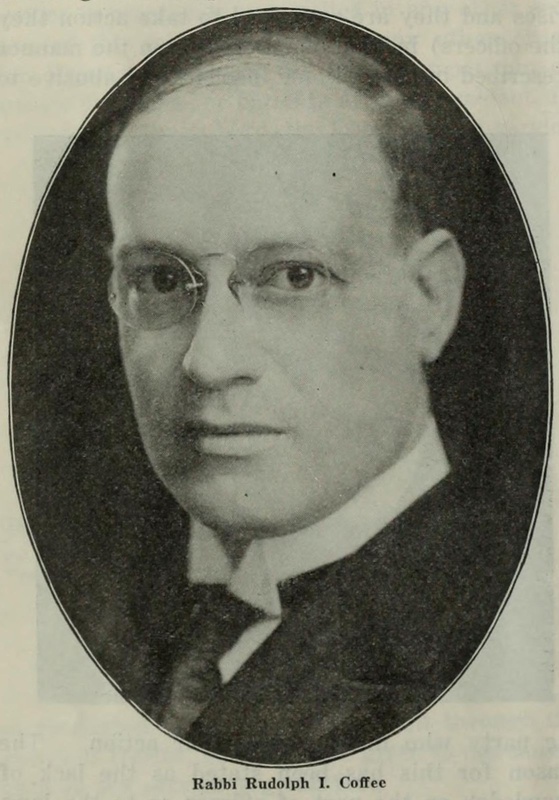

Undeterred, Ioas approached Rabbi Rudolph Coffee, head of the largest synagogue in the Bay Area and the first Jewish person to serve as chaplain of the California State Senate. Coffee shared many of the Bahá’í ideals and became an enthusiastic ally. Ioas again turned to the Bahá’í council, and this time it supported his plan to form a committee that included Cooper and Frankland as members.

The committee’s first order of business was to draft a statement of purpose. It said that the goals of the conference were “to present the public … the spiritual facts concerning the beauty and harmony of the human family, the great unity in the diversity of human blessings, and the harmonizing of all elements of the body politic as the Pathway to Universal Peace.” The group also decided that the expenses of the three-day conference set for March 1925 would be covered by the Bahá’í community so that participants would not be asked to contribute money—but, despite the Bahá’í underwriting of the event, the program would not have any official denominational sponsorship. The committee booked the prestigious Palace Hotel, the city’s first premier luxury hotel, as the venue for the event.

Cooper, listed on the San Francisco Social Registry,191932 San Francisco Social Registry, https://www.sfgenealogy.org/sf/1932b/sr32maid.htm. The social registry is a directory of socially-connected members of high society. had access to the leading citizens of the area. As experienced event organizers, Cooper and Frankland set to work soliciting leading city residents to serve as “patrons”. The greatest coup was enlisting Dr. David Starr Jordan, founding president of Stanford University, to serve as the honorary chairman of the conference. Jordan had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and was known in peace movement circles for having developed his own peace plan. Other note-worthy speakers accepted, and the first World Unity Conference was born. The committee even hired a public relations firm to advertise the event and assist with arrangements.

Over the course of the evenings of March 21, 22, and 23, speakers addressed, before large audiences, the issues of the status of women and of the black, Chinese, and Japanese communities, as well as topics related to world peace. The roster of accomplished presenters included not only Rabbi Coffee and Dr. Jordan but also the senior priest of the Catholic Cathedral, a professor of religion, a Protestant minister of a large African-American congregation, distinguished academics, and a foreign diplomat. The last one to address the conference was the Persian Bahá’í scholar, Mírzá Asadu’llah Fádil Mázandarání, the only Bahá’í on the program.

Measured by attendance and favorable publicity, the conference was an unqualified triumph. But as the last session drew to a close, the inevitable question was put to Ioas by Rabbi Coffee: What next? Hold such a conference annually? The planners did not have an answer. Just like the Smileys, Rabbi Coffee realized that the conference should lead to action. Undertaking one conference had stretched the financial and human resources of the San Francisco Bahá’í community. It had also provided a glimpse of what they could achieve. The ideas presented were, however, scattered to the wind with only the hope that some hearts and minds had been changed.20Chapman, Anita Ioas, Leroy Ioas: Hand of the Cause of God, pp. 45-49.

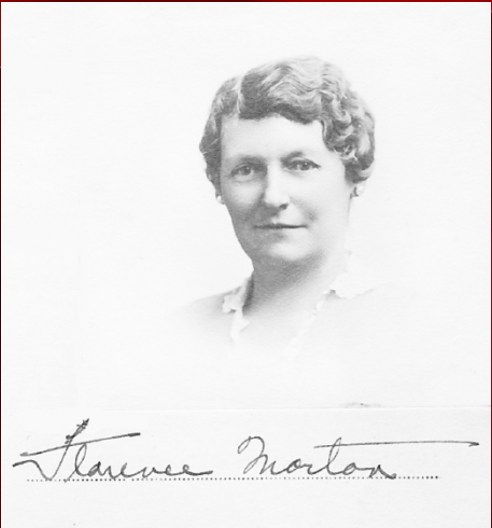

Ioas provided the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada—the governing council for the Bahá’í communities of the two countries—with a report, and he suggested that similar World Unity Conferences be held in other communities. The National Assembly enthusiastically agreed and established a three-person committee, including two of its officers, to assist other localities in their efforts to hold conferences. The committee members were Horace Holley, Florence Reed Morton, and Mary Rumsey Movius.21Bahá’í News Letter: The Bulletin of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, no. 12, June-July 1926, pp. 6-7. Human resources and all funds were to come from the sponsoring communities, but the national committee would help to promote the conferences and offer other assistance, including speakers.

During 1926 and into 1927, eighteen communities held World Unity Conferences. These included Worcester, Massachusetts; New York, New York; Montreal, Canada; Cleveland, Ohio; Dayton, Ohio; Hartford, Connecticut; New Haven, Connecticut; Chicago, Illinois; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Buffalo, New York. They followed the format of the San Francisco conference with three consecutive nights of programs featuring a diversity of speakers—the majority of whom were not Bahá’ís—on topics that were encompassed within Bahá’í principles. Among the presenters were clergy, academics, politicians, including the first woman to serve in the Canadian Parliament,22This was Agnes Macphail, who spoke at the Montreal Conference which was chaired by William Sutherland Maxwell. Nakhjavani, Violette, The Maxwells of Montreal : Middle Years 1923-1937, Late Years 1937-1952, George Ronald, Oxford, p. 74.22 and writers. Some conferences were held in church buildings, others on university campuses, and a few in hotels.

As in San Francisco, the World Unity Conferences provided valuable experience that enhanced the capacities of the hosting Bahá’í communities. They supplied a means for those fledgling communities to obtain positive local publicity and brought the nascent Faith to the attention of civic leaders as a new and growing force for good. Although the conferences were on the whole successful, as in San Francisco, they stretched to the limit local human and material resources. Shoghi Effendi urged the American community to follow-up with the conference attendees who showed the greatest interest,23Shoghi Effendi, Bahá’í Administration: Selected Messages 1922 – 1932, p. 117. but this guidance was not implemented systematically.

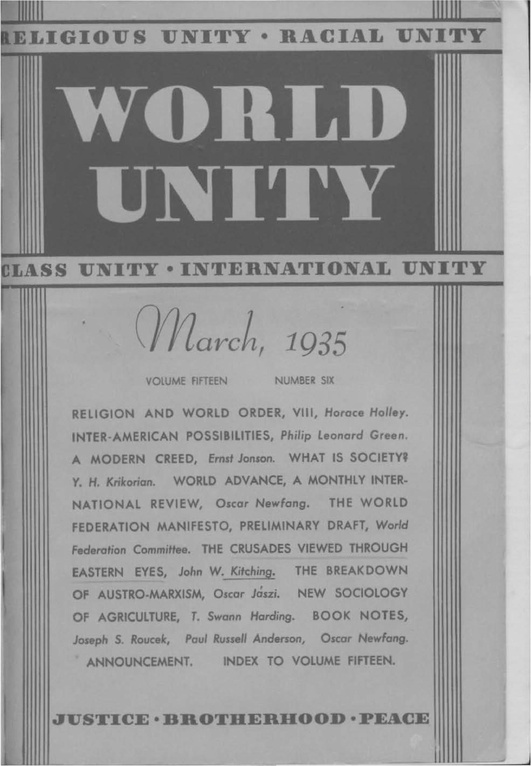

As the series of conferences drew to an end and attention turned to other matters, a growing sense of urgency motivated the three committee members because they took to heart ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s warning that another war greater than the last one was coming; they hoped that bringing the Bahá’í message to the attention of important people might prevent it.24Horace Holley fled Paris, France with his wife and young child at the beginning of WWI in September 1914 and so keenly understood the significance of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s prediction that another war was coming in His second Tablet to the Hague, written after the Great War. Letter from Horace Holley to Albert Vail, October 21, 1925, Vail papers, U.S. Bahá’í National Archives. Mary Movius, in discussing Dr. Randall’s upcoming role as primary spokesman for the World Unity Foundation with him, mentions her concern about where the coming war will start. Letter from Mary Movius to John Randall, June 11, [1927?], U.S. Bahá’í National Archives. They devised a plan to establish a World Unity Foundation that would both sponsor ongoing conferences and provide speakers to other events. In addition, they decided to create a proper organization—a movement—with local councils and a journal titled World Unity. The National Spiritual Assembly approved of the proposal but decided that it should be an individual initiative rather than an official activity of the Faith. The Assembly also encouraged the Bahá’í community to be supportive of the Foundation.25Bahá’í News Letter: The Bulletin of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, no. 20, November 1927, p. 5.

Each of the three members26Montfort Mills, a lawyer from New York City and former chairman of the National Spiritual Assembly was also part of this consultation, but at the time he was engaged in frequent travels abroad on behalf of the work of the Faith. As much as possible, Mills served as an advisor to and promoter of the World Unity Foundation. made important contributions to the new endeavor.

Morton, a prosperous businesswoman who owned a factory, provided most of the funding and served as treasurer. Holley, with a professional background in writing, publishing, and advertising, assumed the management of the journal. Movius, a writer and another source of funds, became president of the board of directors. They hired Dr. John Herman Randall, an ordained Baptist minister and associate pastor of a non-denominational, liberal church—The Community Church in New York City—to be the Foundation’s public face as director and editor.27Randall was one of the two Christian clergymen from New York City who played active roles in the Bahá’í community during the 1920s and 1930s. Shoghi Effendi said, “I am delighted to learn of the evidences of growing interest, of sympathetic understanding, and brotherly cooperation on the part of two capable and steadfast servants of the One True God, Dr. [John] H. Randall and Dr. [William Norman] Guthrie, whose participation in our work I hope and pray will widen the scope of our activities, enrich our opportunities, and lend a fresh impetus to our endeavors.” Bahá’í Administration, p. 82. For a brief summary of Randall’s life see, Day, Anne L., “Randall, John Herman”, Kuehl, Warren F., editor, Biographical Dictionary of Internationalists, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1983, pp. 595 – 97. See also, “John Herman Randall Sr.: Pioneer liberal, philosopher, pacifist” by one of his grandsons [David Randall?] at http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~knower/genealogy/johnhermansrcareer.htm. Randall was a gifted, widely sought-after orator and author who was keenly interested in and sympathetic towards the Bahá’í Faith, even though he was not a professed adherent. Randall had spoken at several of the World Unity Conferences and shared the ideals underlying them. The four individuals then established a non-profit corporation, the World Unity Foundation, with Randall as director and journal editor.28The Board of Trustees of the World Unity Foundation included the following Bahá’ís: Horace H. Holley, Montfort Mills, Florence Reed Morton, and Mary Rumsey Movius. The other members were: Reverend John Herman Randall (non-denominational Protestant), Reverend Alfred W. Martin (Unitarian), and Melbert B. Cary (friend of Dr. Randall). The Honorary Committee for the Foundation were: S. Parkes Cadman, Carrie Chapman Catt, Rudolph I. Coffee, John Dewey, Harry Emerson Fosdick, Herbert Adams Gibbons, Mordecai W. Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Rufus M. Jones, David Starr Jordan, Harry Levi, Louis L. Mann, Pierrepont B. Noyes, Harry Allen Overstreet, William R. Shepherd, Augustus O. Thomas. Bahá’í News Letter: The Bulletin of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, no.22, March 1928, p. 8.

The original plan was that Dr. Randall, working full time for the Foundation, would ensure that World Unity Conferences were held all over the country. The talks from those events would provide the content for the journal, and conference participants would be encouraged to form local councils to carry forward the work of spreading the cause of peace. None of this went as planned, despite a few early successes. Speakers rarely followed through with written versions of their talks. Local committees often dissolved within a year. Limited resources made it impossible to give attention to the innumerable details required to attract and retain a growing membership.29Letter dated July 7, 1932 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, U.S. Bahá’í Archives.

Despite setbacks associated with the conferences, in October 1927, the first issue of World Unity was published, providing an expansive view of the world and current international affairs. It covered not only important peace subjects such as the League of Nations and the Paris (Kellogg-Briand) Pact of 1928—the first attempt to make war illegal—but also articles introducing to the Western reader various countries, religions, arts, and other topics that would engender a sense of world citizenship. The contributors by and large were not Bahá’ís, though the three Bahá’í directors tried to ensure the publication reflected Bahá’í ideals. A number of those featured in its pages had been regular participants at the Lake Mohonk Arbitration Conferences, including leading peace activists Hamilton Holt, Edwin D. Mead and Lucia Ames Mead, and Theodore Marburg. A small number had spoken at World Unity Conferences, among them Dr. Jordan and Rabbi Coffee. Though the majority of articles were written specifically for the magazine, some were taken from speeches or other publications. Over seven years, the magazine published articles by notables such as Nobel Peace Prize recipient Norman Angell; eminent sociologist and advisor to President Wilson, Herbert Adolphus Miller; scholar of international law Philip Quincy Wright; the foremost scholar on auxiliary languages, Albert Léon Guérard, who heard ‘Abdu’l-Bahá speak in California; the first president of the Republic of Korea, Syngman Rhee; the well-known writer and philosopher Bertrand Russell; eminent U.S. foreign policy historian and official historian of the San Francisco Conference to establish the United Nations, Dexter Perkins; Charles Evans Hughes, chief justice of the US Supreme Court; philosopher and influential social reformer John Dewey; socialist, pacifist, and US presidential candidate Norman Thomas; Philip C. Nash, executive director of the League of Nations Association; and Robert W. Bagnell, a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the preeminent American civil rights organization. The journal occasionally carried talks by or about the teachings propagated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed one version of the masthead and also penned an article.30Frank Lloyd Wright was a friend of Horace Holley, who convinced Wright to submit an article. Wright then suggested that he redesign the magazine’s cover. His design, with some modifications, was first used for the October 1929 edition of World Unity. Website: The Wright Library, http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Periodicals/1930-39.htm. (The article quoted on the website assumes that Holley and Wright met through their mutual friend, Dr. Guthrie. Actually, they first met in Italy in 1910. (Letter from Horace Holley to Irving Holley from Florence, Italy, dated Easter Sunday [1910], in the possession of the author.)) But perhaps one of the most praiseworthy attributes of the journal was its inclusion of well-reasoned articles by ordinary people who would have not found another national outlet for their voices.31Day, Anne L., “Randall, John Herman”, Kuehl, Warren F., editor, Biographical Dictionary of Internationalists, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1983, pp. 100-101.

There were two aspects of the work of the Foundation that proved problematic. First, the objectives were lofty, but too broad. For example, the journal’s subhead was: “A monthly magazine promoting the international mind.” This allowed for wide participation in the Foundation’s work, but it also left ambiguous the question of what exactly the journal stood for. In 1932, the Foundation sought to bring greater clarity to this question, first by explicitly promoting the Bahá’í concept of world federation and then by adopting the tenets set forth in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s 1919 letter to the Central Organisation for Durable Peace in The Hague.

A second challenge was that the initial approach taken by the Foundation confused and dismayed many Bahá’ís. In the beginning, the founders were concerned that associating the World Unity Foundation explicitly with religion would turn away some people who otherwise shared Bahá’í ideals and would cause their primary target audience, leaders of thought, to ignore its activities. In fact, the Bahá’í background of the Foundation was so well-concealed that most who have written about it after it was discontinued have also believed that Dr. Randall was its sole founder and proponent. 32Most of what is published about Dr. Randall’s work with the World Unity Foundation is derived from memorials to him written by his descendants or from his own books. To address the confusion that had arisen, the magazine began in 1933 to include articles explicitly based on the Bahá’í Faith.33The decision to make the magazine more openly Bahá’í was taken in 1932. Letter dated October 28, 1932 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, page 2, U.S. Bahá’í Archives. In a 1933 letter to Morton, Holley pointed out to her how he was trying to “build a bridge of sympathetic understanding between World Unity readers and the Articles of the Cause which will be published later on” through his more recent editorials. Letter dated February 2, 1933 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, page 2, U.S. Bahá’í Archives. See also an explanation of the careful transition to Bahá’í content in letter dated January 7. 1933 from Horace Holley to Mary Movius, U.S. Bahá’í Archives. During its last years of publication, it was openly a Bahá’í journal.

Because of the controversy the Foundation generated within the Bahá’í community, Shoghi Effendi addressed the matter in a letter to the National Spiritual Assembly, discussing at length the approach of putting forth the Bahá’í message without mentioning the source of the ideas. Referring to the World Unity Conferences held earlier by Bahá’í communities, he wrote, “I desire to assure you of my heartfelt appreciation of such a splendid conception.” He then explored why a variety of approaches, both direct and indirect, to conveying the teachings of the Faith were appropriate and desirable if executed with thoughtful care under the supervision of a National Spiritual Assembly.34Shoghi Effendi, Bahá’í Administration, pp. 124 -28.

Just as the Foundation and its journal were gaining traction, they encountered one challenge that could not be overcome: The Great Depression of the 1930s. Morton could no longer pay her factory employees, much less continue to fund the organization. Movius experienced her own economic setbacks. Randall resigned at the end of 1932. In a last effort to save the journal, Holley took over as editor.35Both Randall and Holley were paid for their services, but after the financial crisis started, Holley took a cut in salary even as his responsibilities increased. For a time, he drew no pay but funded the journal from his own savings. Letter dated April 1, 1933 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, U.S. Bahá’í National Archives. But the times were against it. The world’s rapid march towards war was already underway. Peace movements seemed out of touch and magazines promoting their ideals became a luxury. No matter the sacrificial strivings of the proponents of the World Unity Foundation, their resources proved insufficient to further any interest that had been generated. As Movius wrote to Holley, “I like extremely the editorials you are writing for ‘World Unity,’ and only hope they will bear fruit. They will, undoubtedly, even if we never hear of it.”36Both Randall and Holley were paid for their services, but after the financial crisis started, Holley took a cut in salary even as his responsibilities increased. For a time, he drew no pay but funded the journal from his own savings. Letter dated April 1, 1933 from Horace Holley to Florence Morton, U.S. Bahá’í National Archives.

Finally, in 1935, after consulting the institutions of the Bahá’í Faith, it was decided to merge World Unity with another publication, Star of the West (renamed The Bahá’í Magazine in its later volumes) to become a new entity, World Order.37Bahá’í News, no. 90, March 1935, p. 8. This magazine was published from 1935 to 1949, revived in 1966, and ran until 2007. Like World Unity, its erudite articles covered a wide range of topics aimed at the educated public, but it was unmistakably a Bahá’í organ under the auspices of the US National Spiritual Assembly and never acquired as broad a readership as World Unity.

Did the World Unity Foundation and its journal have any impact? The renowned head of the Riverside Church in New York City, Harry Emerson Fosdick, said of World Unity Magazine that it represented, “one of the most serious endeavors … to use journalism to educate the people as to the nature of the world community in which we are living.”38Undated World Unity circular. U.S. Bahá’í Archives. Perhaps the foremost scholar of internationalism during the early twentieth century, Warren F. Kuehl, listed the magazine as one of only a tiny handful at the time discussing issues promoting peace through international order, noting that it seemed unique in its advocacy of a world federation.39Kuehl, Warren F. and Lynne Dunn, Keeping the Covenant: American Internationalists and the League of Nations, 1920-1939, Kent State University Press, 1997, p. 73 Another scholar of diplomatic history, Anne L. Day, concluded that World Unity’s primary contribution was creating a space for lesser-known people interested in international peace to put forth their ideas.40Kuehl, Warren F. and Lynne Dunn, Keeping the Covenant: American Internationalists and the League of Nations, 1920-1939, Kent State University Press, 1997, pp. 100-101

… the conferences and the magazine helped foster a world outlook without prejudice and a faith in humanity which survived the horrors of World War II. World Unity Magazine gave young scholars a medium to which they could hone their insights toward global humanitarian values, thus broadening consciousness to recognize the moral and spiritual equality, “to realize that the interests of all men are mutual interests.”41Day, Anne L., “Randall, John Herman”, p. 596.

The World Unity Foundation was formally dissolved just as armies were moving into a growing number of hot spots in Europe and Asia. Within a few short years, much of the globe would be plunged into the most horrible conflict mankind had ever known. As the end of World War II came into view, a few far-sighted leaders became determined that such a catastrophe should never afflict humanity again and looked to the future. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for an international conference to be held in October 1945 to create a new organization of countries that would improve upon the impotent League of Nations. The United Nations would be born that year.

That historic conference was held in San Francisco, fulfilling ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s wish that California would be the first place to hoist the banner of international peace. Seated in the audience were official representatives of the worldwide Bahá’í community, including Holley’s close friend and protégé, Mildred Mottahedeh, who would later serve as the Faith’s representative to the United Nations. Indeed, from the very inception of the United Nations, the Bahá’í International Community (BIC) has actively participated in its work as an official non-governmental organization.