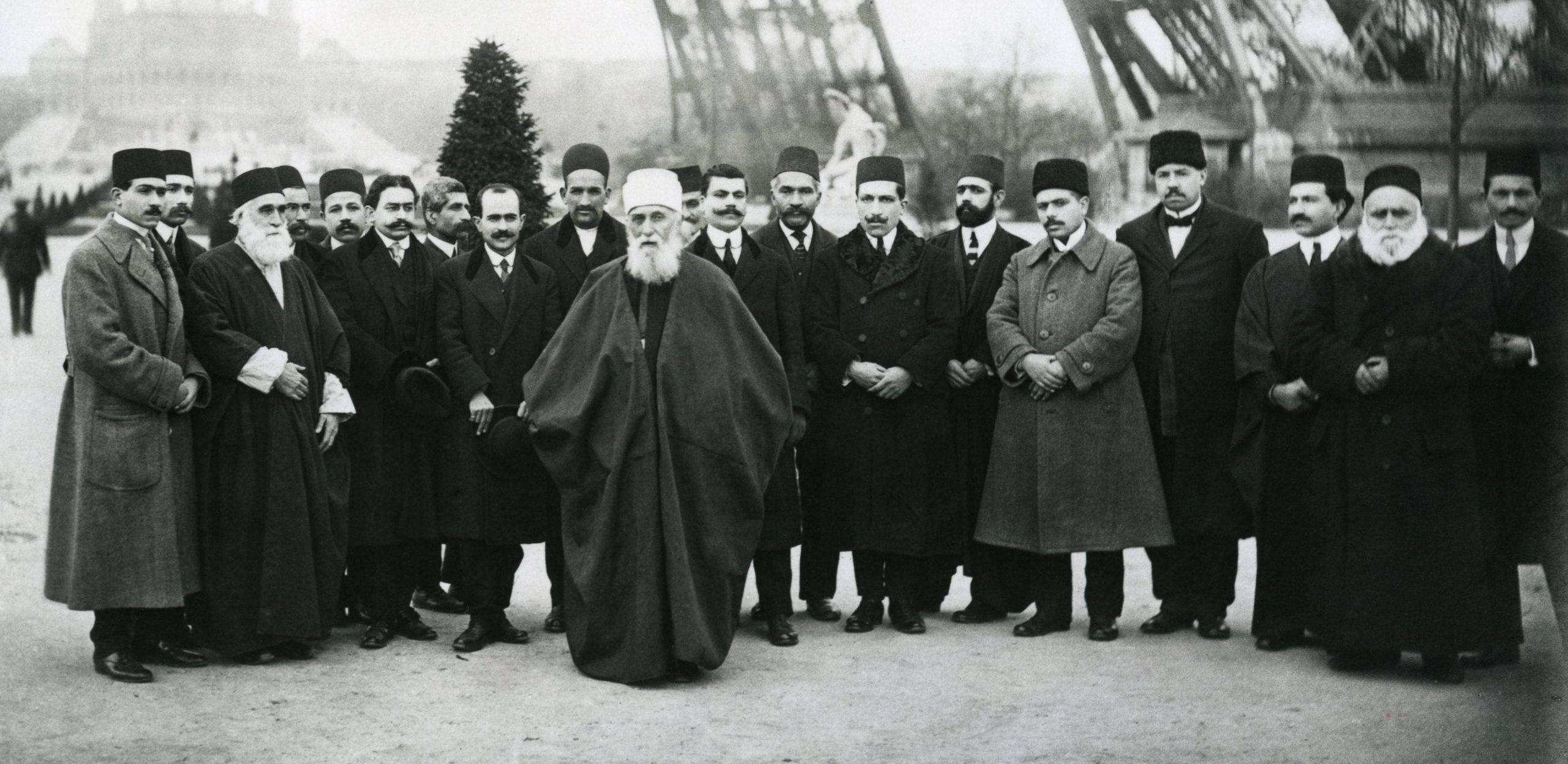

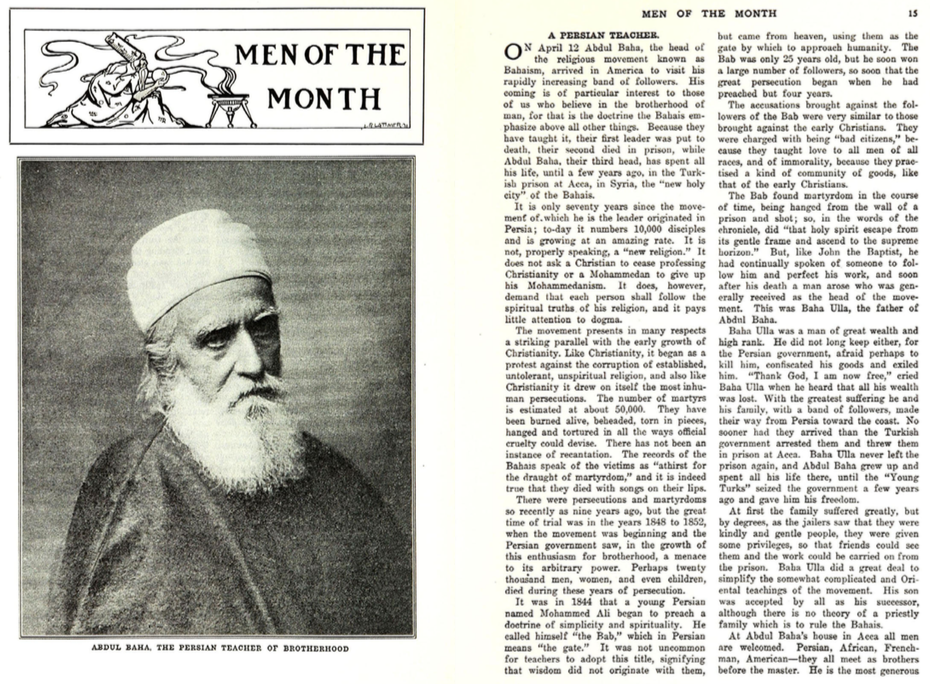

On 10 September 1911 and at the age of 67 years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá delivered the first public address of His life. From the pulpit of the City Temple in London, He announced to the reported 3,000-strong congregation: “This is a new cycle of human power.” Humanity’s dynamic acceleration toward greater levels of unity, He explained, was a consequence of the “light of Truth … shining upon the world.”1‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.19.

Throughout the ensuing two years of His travels, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá—finally free after more than half a century of imprisonment and exile—continued to elucidate, in both open presentations and private conversations, the distinctive capacities of humanity in this “new day.”2‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.19. In Paris, for example, He stated:

Look what man has accomplished in the field of science, consider his many discoveries and countless inventions and his profound understanding of natural law.

In the world of art it is just the same, and this wonderful development of man’s faculties becomes more and more rapid as time goes on. If the discoveries, inventions and material accomplishments of the last fifteen hundred years could be put together, you would see that there has been greater advancement during the last hundred years than in the previous fourteen centuries.3‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Paris Talks. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing, 2006, p.84.

By the early years of the twentieth century, such advances were familiar in the Western societies into which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá ventured, which had been impacted by the scientific challenge to Bible-centric worldviews, technological progress and urbanization, shifts in governance and global consciousness, the intensification of financial exchange and improvements to the status of women. These and numerous other advancements—also taken up in distant corners of the planet, many of which had been annexed, colonized and influenced by Imperialist powers—are often included in the humanities and social sciences as some of the characteristics of “modernity.”

Concurrently, a wide variety of beliefs and practices later labelled ‘modernist’ were taking root. Ideals of truth, reason, and liberty were shared through diverse branches of human thought and endeavor, ranging from the materialistic to the esoteric. For the purposes of this exploration pertaining particularly to cultural pursuits, ‘modernism’ might be seen as both an outcome and, at times, a rejection of aspects of modernity. Rebelling against widely accepted norms, modernists in the arts set out to shun tradition and break rules, or at least push them to their limits. Painters dismissed the accurate depiction of reality, exploring instead the expressive and space-defining potential of color, experimented with abstracted forms, and revealed their process in the creation of an image; composers tested novel approaches to melody, harmony and rhythm; dancers drew upon the gestures of daily life or looked back to ancient civilizations for physical movements that stretched the possibilities of bodily expression; writers and dramatists departed from the established rules of prose, poetry, and playwriting to articulate the new sensibilities of the time. Some modernists conceived of utopian visions of society, albeit in certain cases by spreading the supremacy of their own nationalistic cultural heritage over neighboring traditions. At the heart of all of this burgeoning experimentation, however, was an aspiration for change, to which the subjective ‘self’ of the practitioner was central.

Ironically, while modernists often scorned uniformity and the imposition of Western values on the earth’s populations, they also turned for inspiration to the very cultures that were then becoming even more familiar to the public as a result of the expansionist ambitions of the powers under which they lived. A new universal art, some modernists believed, would emerge as they opened their eyes to what they considered to be the exciting, radical, and inventive qualities of the folk art and tribal crafts of the colonies, on display in museums and great expositions. Often it was the enormous wealth—extracted from colonialized subjects abroad and exploited lower classes at home—that enabled modernist projects, pursuits, and indulgences in the West.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, when Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution began to mount its challenge to the Biblical, anthropocentric conception of creation, the search for “an exotic and syncretic world religion” also became “an early modernist aim.”4Bernard Smith. Modernism and Post-Modernism, a neo-Colonial Viewpoint. Working Papers in Australian Studies, Sir Robert Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, 1992 New translations made accessible such religious texts as The Upanishads, The Bhagavad-Gita, and the Tao Te Ching. Elements of the religions of India and Tibet—and the more mystical strands of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—were incorporated into modernist thinking, often through the teachings of the Theosophical Society, and especially among women seeking a spirituality that cut out the literal middle man.

Such was the burgeoning cultural landscape in the West when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived with His message of the dawning of a new era in human evolution, in which the unity and equality of all humanity would be recognized and conflict and contention would give way to an enduring peace.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s discourse on progress was rooted in the conviction that the discoveries and developments of the age represented an instinctive response on the part of humanity to a new infusion of divine power into creation. Fundamental to the Bahá’í conception of history is the belief that, when a Manifestation of God appears in the world, the accompanying forces required to accomplish His divinely-ordained purpose are also released, setting in motion irresistible processes of societal transformation. Bahá’u’lláh proclaimed:

The world’s equilibrium hath been upset through the vibrating influence of this most great, this new World Order. Mankind’s ordered life hath been revolutionized through the agency of this unique, this wondrous System—the like of which mortal eyes have never witnessed.5Bahá’u’lláh. Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1978, LXX, p.135.

The spiritual forces released by the Revelations of the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh were thus breaking down barriers and pushing an unknowing humanity toward the consciousness and realisation of its essential oneness, regardless of race, gender, class, or other divisive factors. Such forces had deranged the stability of the existing world order and instigated transformation at every level:

Through that Word the realities of all created things were shaken, were divided, separated, scattered, combined and reunited, disclosing, in both the contingent world and the heavenly kingdom, entities of a new creation …6Bahá’u’lláh. Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1978, LXX, p.135.

These “spiritual, revolutionary forces,” observed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s grandson Shoghi Effendi, Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith, “… are upsetting the equilibrium, and throwing into such confusion, the ancient institutions of mankind.”7Shoghi Effendi. The Promised Day is Come. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1980, p.95 Humanity, either in its overt resistance to—or in its attempts to stimulate—social transformation was, in Shoghi Effendi’s analysis, experiencing the “commotions invariably associated with the most turbulent stage of its evolution, the stage of adolescence, when the impetuosity of youth and its vehemence reach their climax …”8Shoghi Effendi. ‘The Unfoldment of World Civilization’, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1991, p.202 While the internal physiological processes within an individual trigger the onset of adolescence, the release into the world of Divine Revelation affects the inner fibre of human life and thought, and has an impact far beyond the personal orbit of a Manifestation of God and those who physically hear His message or respond directly to His call. It suffuses every aspect of existence and at a subliminal level is received by sensitive human hearts and minds, as yet oblivious to its source.

At the time of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s arrival in Paris on 3 October 1911, the French capital was maintaining its status as the most fertile arena for artists, writers, and musicians—including countless Americans—engaged in a passionate quest to live and work free from stifling convention. “I like Paris because I find something here, something of integrity, which I seem to have strangely lost in my own country,” wrote the African-American writer Jessie Redmon Fauset. “It is simplest of all to say that I like to live among people and surroundings where I am not always conscious of ‘thou shall not.’”9Shari Benstock. Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900-1940. London: Virago, 1986, p.13 For women such as Fauset, who were escaping their homeland, where even educated Black citizens were still prohibited from participating in most social spaces, Paris offered the opportunity for fearless experimentation and acceptance. It was a city in which scientists such as the Polish Nobel Prize-winning physicist and chemist Marie Curie could train and embark on their careers, and where literary salons—including those hosted by expatriates Gertrude Stein and Natalie Clifford Barney—flourished, offering spaces where artists and writers could uninhibitedly share their ideas and work.

Women had also played a significant role in the establishment, in Paris, of the first Bahá’í centre in Europe at the close of the nineteenth century. Through the efforts of May Ellis Bolles (later Maxwell), many important figures in early Western Bahá’í history embraced the message of Bahá’u’lláh in the city. Among them were other Americans and Canadians, including painters such as Juliet Thompson and Marion Jack, and heiress Laura Clifford-Barney, Natalie’s sister. Impressionist painter Frank Edwin Scott, architect William Sutherland Maxwell, poet and art gallery manager Horace Holley and the Irish-born philanthropist Lady Blomfield also first came across the Bahá’í teachings in Paris. Experimental dancer Raymond Duncan, brother of the more renowned Isadora, and composer Dane Rudhyar were included in the Bahá’í circle. Rudhyar was a modernist who intuitively felt that Western civilization was coming to “the autumn phase of its cycle of existence.”10Rudhyar Archival Project. http://www.khaldea.com/rudhyar/bio1.shtml Later composing Commune—based on the words of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá— Rudhyar deemed the Bahá’í message to have embodied “clearly the most basic keynotes of the collective spirit of the age …”11Dane Rhudyar, cited in The Bahá’í World Vol. XIII 1954-1963. Haifa: The Universal House of Justice, 1970, p.829

To exhausted communities of the world [the Bahá’í Revelation] gives vital impetus which, we hope, will soon energize new creative manifestations and produce an inspired art, equal or superior to that of early Christianity.12Dane Rhudyar, cited in The Bahá’í World Vol. XIII 1954-1963. Haifa: The Universal House of Justice, 1970, p.829.

Many artists and writers of the period were continuing to take a Symbolist approach. As a prelude to more far-reaching forms of abstraction, Symbolists strove to represent universal truths through metaphorical language and imagery, in an attempt to “illumine the deepest contradictions of contemporary culture seen through the prism of various cultures.”13Andrei Bely. The Emblematics of Meaning: Premises to a Theory of Symbolism, 1909 The novelist Andrei Bely wrote:

… we are now experiencing, as it were, the whole of the past: India, Persia, Egypt, Greece … pass before us … just as a man on the point of death may see the whole of his life in an instant … An important hour has struck for humanity. We are indeed attempting something new but the old has to be taken into account …14Andrei Bely. The Emblematics of Meaning: Premises to a Theory of Symbolism, 1909

It seems natural, then, that the opportunity to see in person a striking, venerable figure from Persia was intriguing to those who sought enlightenment from the East to find a language appropriate for expressing the modern world. The influential critic and Symbolist poet Remy de Gourmont, for example, met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Paris on 20 October 1911. From Gourmont’s account, published in La France, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá appears to have been alert to the fact that he was a writer for whom a metaphorical depiction of spiritual reality would have appeal:

… The eloquent patriarch spoke to us of the simple joys experienced in the Bahá’í city, of pleasures designed to delight the docile hearts, where spring is eternal, ever-flowering with the perpetual blooming of lilies, violets and roses, where women smile and men are happy in the perfume air of love. And we spoke of the great truth that excels all the previous truths, in which our little human errors are melted and transformed, as such quarrels disappear in the shade of the greatest Peace. And we felt a deep passion in the faintly halting voice, roughly punctuated by the guttural sounds of the Persian language, but also gently punctuated by the phrasing of his musical laughter. For the prophet is joyful and we all feel within him the gaiety of being a prophet, upon whom forty years of prison have left no trace. He had with him a bouquet of violets, offering one to each of his visitors; to the most resistant to his teachings and to those who had the audacity to stubbornly oppose him, the parma violets serve as his arguments, as do his hearty laugh, his beautiful and poetic arguments, and the simplicity of his Persian dress.15 See Amin Egea. The Apostle of Peace Vol.1: 1871-1912. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 2017, p.164.

Evidently touched by their exchange, Gourmont urged his readers to seek out ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s public appearances. Subsequently, using a pseudonym, Gourmont even penned a review of his own La France article for another journal.

Another significant modernist who learned of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was Guillaume Apollinaire, although whether they met is not known. One of the foremost poets of the early twentieth century and a close associate of such emerging painters as Picasso, Braque, and Marie Laurencin, Apollinaire is credited with coining the terms “Cubism” in 1911 and “Surrealism” in 1917. His “Le Béhaisme” appeared in the Mercure de France on 17 October 1917. That article concludes:

A new voice is coming out of Asia. Already many in Europe believe that the word of Beha-Oullah[sic] does not contradict our modern science and can be assimilated for we[sic] Europeans, who need comforting. Isn’t it just that this comfort comes to us from Asia as it came before?16Guillaume Apollinaire, “Le Béhaisme.” Mercure de France, 16 October 1917, p.768

In like manner, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s stay in London was widely reported in the publications of the day. One weekly magazine, aptly titled The New Age and supported by the future Nobel Prize-winning writer George Bernard Shaw, was dedicated to publishing modernism in literature and the arts. In its 21 September 1911 edition, two weeks after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s arrival in the city, The New Age reported, “Seeds of strange religions are wafted from time to time on our shores. But fortunately or unfortunately, they do not find the soil in us in which to flourish … The latest to land in public is Bahaism, of which, indeed many of us have heard in private these many years.”17A.R. Orage. “Notes of the Week.” New Age 9, September 1911, p.484

The pioneering modernist poet Ezra Pound was a regular contributor to The New Age. The day after “Bahaism” was mentioned in its pages, Pound stated somewhat arrogantly to his future wife, Dorothy Shakespear, “They tell me I’m likely to meet the Bahi[sic] next week in order to find out whether I know more about heaven than he does …’18Ezra Pound, cited in Elham Afnan, “‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Ezra Pound’s Circle”, The Journal of Bahá’í Studies Volume 6 No.2, June-September 1994, p.8 Following their meeting, Pound then wrote to Margaret Cravens, a friend who lived in the French capital, “I met the Bahi yesterday, he is a dear old man. I wonder would you like to meet him, he goes to Paris next week. I’ll arrange for you anyhow and you can go or not, as you like.”19Omar Pound and Robert Spoo, editors. Ezra Pound and Margaret Cravens: A Tragic Friendship 1910-1912. Durham: Duke University Press, 1988, p.90. In a further communication to Cravens, Pound was clearly eager for his friend to see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, placing His significance above that of the French post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne:

The Bahi—Abdul Baha, Abbas Effendi, or whatever you like to call him is at the Dreyfus Barney’s … and any one interested in the movement can write and see him there by appointment. It’s more important than Cezanne, & not in the least like what you’d expect of an oriental religious now. At least, I went to conduct an inquisition & came away feeling that questions would have been an impertinence. The whole point is that they have done instead of talking …20Omar Pound and Robert Spoo, editors. Ezra Pound and Margaret Cravens: A Tragic Friendship 1910-1912. Durham: Duke University Press, 1988, p.95.

Despite Pound’s later, well-documented inclination towards fascism—which is about as ideologically far removed as can be imagined from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s purpose—it nevertheless appears that he was momentarily disarmed by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The poet even revived his memory of that day more than two decades later in his monumental verse cycle The Cantos. “Pound did not interest himself in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s message beyond expressing approval of its unexpected modernity,” literature scholar Elham Afnan has observed, yet the “portrait of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá [in Canto XLVI], despite its flippancy, is basically sympathetic and as respectful as Pound can manage to be.”21Elham Afnan, “Abdu’l-Bahá and Ezra Pound’s Circle”, p.11.

Pound was also a contributor to the modernist journal Blast, in which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s name appeared in a somewhat surprising fashion. Blast was the creation of the painter and novelist Percy Wyndham Lewis, founder of the short-lived Vorticist movement, which was inspired by the Cubism of Picasso and Braque, and the Italian Futurists’ celebration of the machine age. The first edition of Blast contained an extensive list of people, institutions, and objects that were, in the Vorticist view, either “Blessed” or “Blasted.” Curiously, included among those “Blasted” is the name “Abdul Bahai.” Since there is no record of Wyndham Lewis having met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the inclusion of His name in such a provocative list is perhaps more indicative of the contempt in which Blast’s editors held organized religion, or anything they deemed “bourgeois” and “establishment,” which may have encompassed the involvement of wealthy Londoners in Eastern movements.

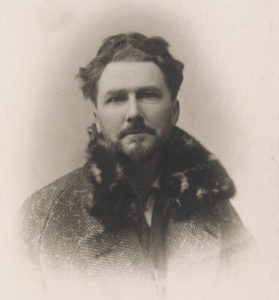

In time, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s fame reached and impacted modernists much farther afield than the cities in which He spoke. In August 1911, the influential Japanese writer Yone Noguchi had sent Ezra Pound two books of his poems. Pound was very taken with Noguchi’s work, saying, “If east and west are ever to understand each other that understanding must come slowly and come first through art.”22Cited in Howard J.Booth and Nigel Rigby, Modernism and Empire. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000, p.82.

Noguchi later learned of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá from Agnes Alexander, a Hawaiian-born Bahá’í who had been sent by Him to share the Bahá’í Teachings in Japan.23Agnes Baldwin Alexander, History of the Bahá’í Faith in Japan 1914-1938. Tokyo: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1977, p.41. Noguchi wrote:

I have heard so much about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, whom people call an idealist, but I should like to call Him a realist, because no idealism, when it is strong and true, exists without the endorsement of realism. There is nothing more real than His words on truth. His words are as simple as the sunlight; again like the sunlight, they are universal. … No Teacher, I think, is more important today than ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.24Yone Noguchi, cited in The Bahá’í World Vol. VIII 1938-1940. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981, p.624.

During the early days of the First World War, Agnes Alexander also introduced the Bahá’í Faith to the highly influential English potter Bernard Leach, who recalled: “We asked what had brought her to Japan and I was struck by the quietness of her smile when she answered ‘… you will not understand, but I came because a little old Persian Gentleman asked me to come.’”25Bernard Leach, “My Religious Faith” in Robert Weinberg, ed., Spinning the Clay into Stars. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 1999, p.60. Leach—who became the most significant figure in the revival of craft pottery in modern Britain—dedicated his entire life to encouraging the union of East and West, fully embracing the Bahá’í Faith in 1940 after he was re-introduced to it by the American painter Mark Tobey, when they were both teaching at the progressive arts school Dartington Hall in Devon, England.

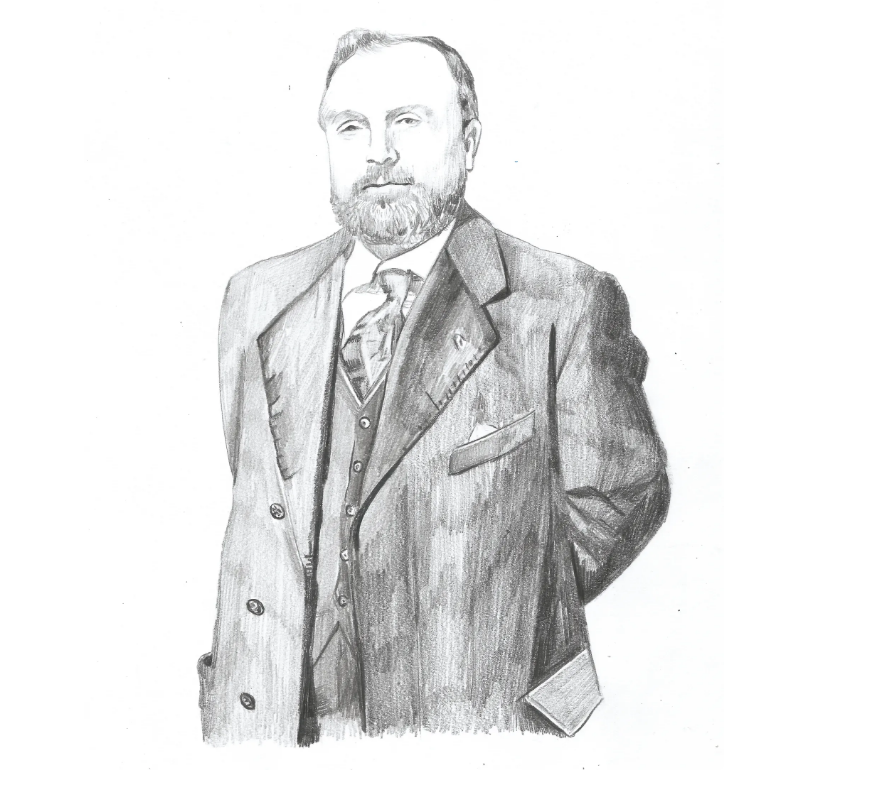

Also favorable in his response to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was another enthusiast for modernism, Professor Michael Sadler. A progressive educationalist and university administrator, Sadler was president of the Leeds Arts Club, which mixed socialist and anarchist politics with the philosophy of Nietzsche, suffragette feminism, Theosophy, avant-garde art, and poetry. Sadler built up a remarkable collection of art, including a Symbolist masterpiece by Paul Gauguin and works by the Russian Expressionist painter Wassily Kandinsky, at a time when his paintings were either unknown or dismissed in London, even by well-known supporters of modernism. In Kandinsky’s seminal 1911 treatise, Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), translated into English by Sadler’s son, the painter proposed that abstraction in painting was the best weapon for transforming a corrupt, materialist society.

Michael Sadler presided over ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s farewell talk at the conclusion of His first visit to London, on 29 September 1911, saying:

We have met together to bid farewell to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, and to thank God for his example and teaching, and for the power of his prayers to bring Light into confused thought, Hope into the place of dread, Faith where doubt was, and into troubled hearts, the Love which overmasters self-seeking and fear.

Though we all, among ourselves, in our devotional allegiance have our own individual loyalties, to all of us ‘Abdu’l-Bahá brings, and has brought, a message of Unity, of sympathy and of Peace. He bids us all be real and true in what we profess to believe; and to treasure above everything the Spirit behind the form. With him we bow before the Hidden Name, before that which is of every life the Inner Life! He bids us worship in fearless loyalty to our own faith, but with ever stronger yearning after Union, Brotherhood, and Love; so turning ourselves in Spirit, and with our whole heart, that we may enter more into the mind of God, which is above class, above race, and beyond time.26‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.34.

In January 1913, when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá travelled to Edinburgh, Scotland’s main proponents of modernist painting—known as the Scottish Colourists—were working abroad in France, where their pictures were exhibited and sold predominately by the Paris gallery managed by Horace Holley. Symbolism, however, was a strong component of the Celtic Revival movement, in which artists and writers drew inspiration from the ancient myths and traditions of Gaelic literature and the early British mediaeval style to create art in a modern idiom. While in Edinburgh, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke with a number of artists through introductions from leading Celtic Revivalist Sir Patrick Geddes, the celebrated philanthropist and town planner (who also had the dubious honor of being “blasted” by Wyndham Lewis). Geddes presided over a public gathering with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, saying of Him:

We approve of the ideal He lays before us of education and the necessity of each one learning a trade, and His beautiful simile of the two wings on which society is to rise into a purer and clearer atmosphere, put into beautiful words what was in the minds of many of us. What impressed us most is that courage which enabled Him, during long years of imprisonment, and even in the face of death, to hold fast to His convictions.27H.M. Balyuzi. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 1971, p.365.

Geddes invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to visit a protégé of his, the painter John Duncan and Duncan’s wife Christine who had connections to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s friends Wellesley Tudor Pole and Alice Buckton, who shared in her Spiritualist interests. Among Duncan’s paintings, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá viewed St. Bride—now housed in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art—depicting the Irish saint who, legend has it, was transported by angels from Ireland to Bethlehem to attend the birth of Christ. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reportedly blessed the paintings, much to the delight of the Duncans.

At the Edinburgh College of Arts, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also encouraged a prize-winning sculptor, Fanindra Nath Bose, from Calcutta. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá praised Bose’s work, suggesting he return to India to found a new school of sculpture.28H.M. Balyuzi. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 1971, p.11. Later in 1913, Bose relocated to Paris to work under the great sculptor Auguste Rodin, which led to his becoming part of the “new sculpture” movement in Britain, creating small, figurative, Symbolist statues.

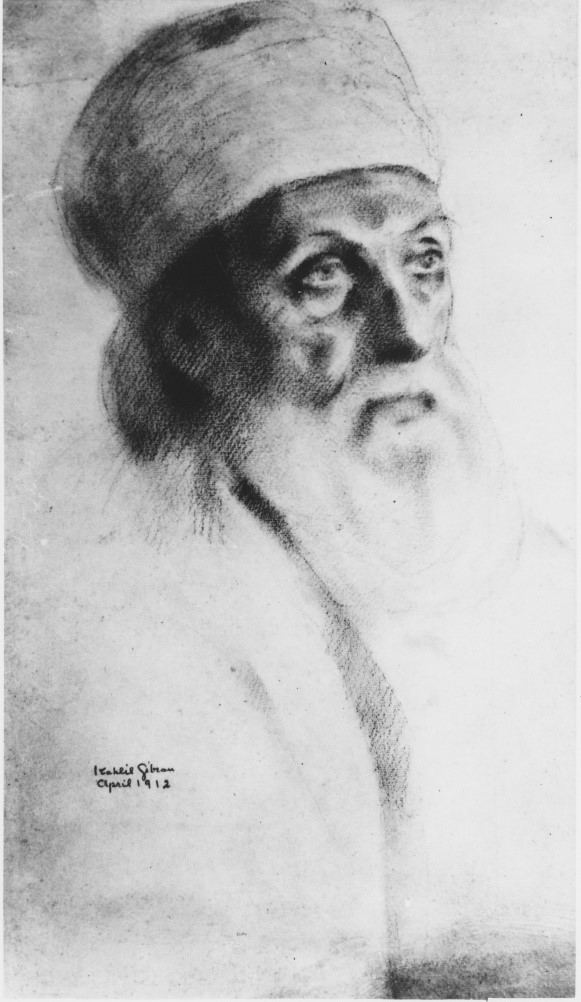

In addition to conversing with artists, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá occasionally agreed to have His portrait painted. During the nine days in April 1913 that He stayed in Budapest, Hungary, He sat three times for Róbert Nádler, a celebrated painter and teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts and president of the city’s Theosophical Society. Two decades later, Nádler warmly recalled the experience, saying, “I saw with admiration that in his facial expression peace, clean love, and perfect good intentions reflected themselves. He saw everything in such a beatific light; he found everything beautiful the outer life of the city, as well as the souls of its inhabitants.”29Cited in Martha Root, “‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Visit to Budapest”, in Kay Zinky, ed., Martha Root: Herald of the Kingdom. New Delhi: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1983, pp.361-370 Nádler’s sympathetic painting of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is unique among the portraits made of Him, taking an Impressionistic impasto approach, particularly in the treatment of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s gossamer-like beard, made up of rhythmic brushstrokes.

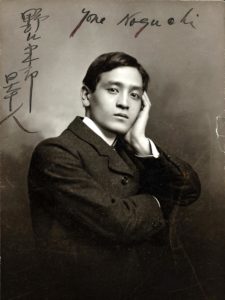

uring ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s nine-month sojourn in North America, the most well-known literary personality to encounter Him was the Syrian-born, Lebanese-American writer and artist Kahlil Gibran, a central figure of Arabic literary modernism. Gibran arrived in New York City at the end of April 1911, his creative horizons having expanded during his exposure to modernists in Paris. Greenwich Village, where Gibran settled, was a gathering place for radical political and bohemian thinkers who were committed to an imminent revolution in human consciousness and social change. Art, they believed, would provide people with new values, giving rise to a new social order. In 1913, modern European art arrived forcefully in New York, when astonished Americans saw for the first time more than 300 avant-garde works at the infamous Armory Show. While remaining unmoved by most of the pieces on display, Gibran was sensitive to the motivations of modern artists, saying, “… the spirit of the movement will never pass away, for it is real—as real as the human hunger for freedom.”30Jean Gibran and Kahlil Gibran. Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World. Edinburgh, Canongate Press, 1992, p.252

Gibran “simply adored” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, recalled Juliet Thompson, who was Gibran’s neighbour. “He was with Him whenever he could be.”31Marzieh Gail, “Juliet Remembers Gibran”, Other People, Other Places. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, p.230. On 19 April 1912, Gibran sketched a portrait for which ‘Abdu’l-Baha sat and, for the rest of his life, “often talked of Him, most sympathetically and most lovingly.”32Marzieh Gail, “Juliet Remembers Gibran”, Other People, Other Places. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, p.230. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá may well have been a source of inspiration for Gibran’s most famous work, The Prophet. The name of the book’s main protagonist Almustafa, it has been posited, resembles that of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá with only the consonants changed,33See David Langness, ‘The Bahá’í influence on Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet’. https://bahaiteachings.org/bahai-influence-on-kahlil-gibrans-the-prophet/ and the villagers in the narrative refer to him as ‘The Master,’ an appellation commonly used in relation to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. While Thompson did not later recall there being any definite connection between The Prophet and Gibran’s meeting with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the author did tell her that when he was writing The Son of Man, “he thought of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá all through.”34Gail, Other People, Other Places, p.228 He also expressed his intention—though it was never realised—to write a book specifically about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Juliet Thompson also arranged for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to sit for the outstanding photographer Gertrude Käsebier. Since 1899, Alfred Stieglitz—a prominent New York gallery owner who championed American modernism—had promoted photography through his ‘Photo-Secession’ movement, which aimed to advance photography as a serious new art form and exhibit the finest work by American practitioners. Käsebier, who Stieglitz deemed to be the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day, was at the heart of Photo-Secession and believed the medium could be a particularly suitable art form and source of income for women. “I earnestly advise women of artistic tastes to train for the unworked field of modern photography,” she said in a lecture. “It seems to be especially adapted to them, and the few who have entered it are meeting a gratifying and profitable success.”35Cited in Stephen Petersen and Janis A. Tomlinson, eds. Gertrude Kasebier – The Complexity of Light and Shade. University of Delaware Press, 2013, p.11.

Käsebier had distinguished herself by her sympathetic, powerful portraits of America’s indigenous peoples, focusing on their expressions and individuality, rather than costumes and customs, a sensitivity she deployed in her portrait session with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on 20 June 1912. “I shall never forget the Master’s beauty in the strange cold light of her studio,” wrote Thompson in her diary, “a green, underwater sort of light, in which He looked shining and chiselled, like the statue of a god. But the pictures are dark shadows of Him.”36Juliet Thompson. The Diary of Juliet Thompson. Los Angeles: Kalimát Press, 1983, p.317. Kasebier, though, told Thompson afterwards, that she would like to live near Him.

Although those who came into contact with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá were deeply impacted by His presence and personality, some appear not to have consciously or explicitly made the profound connection between the Revelation He propagated and the revolutionary period during which they were making their distinctive mark. Yet, other leading modernists did respond more directly and thoughtfully to His Message.

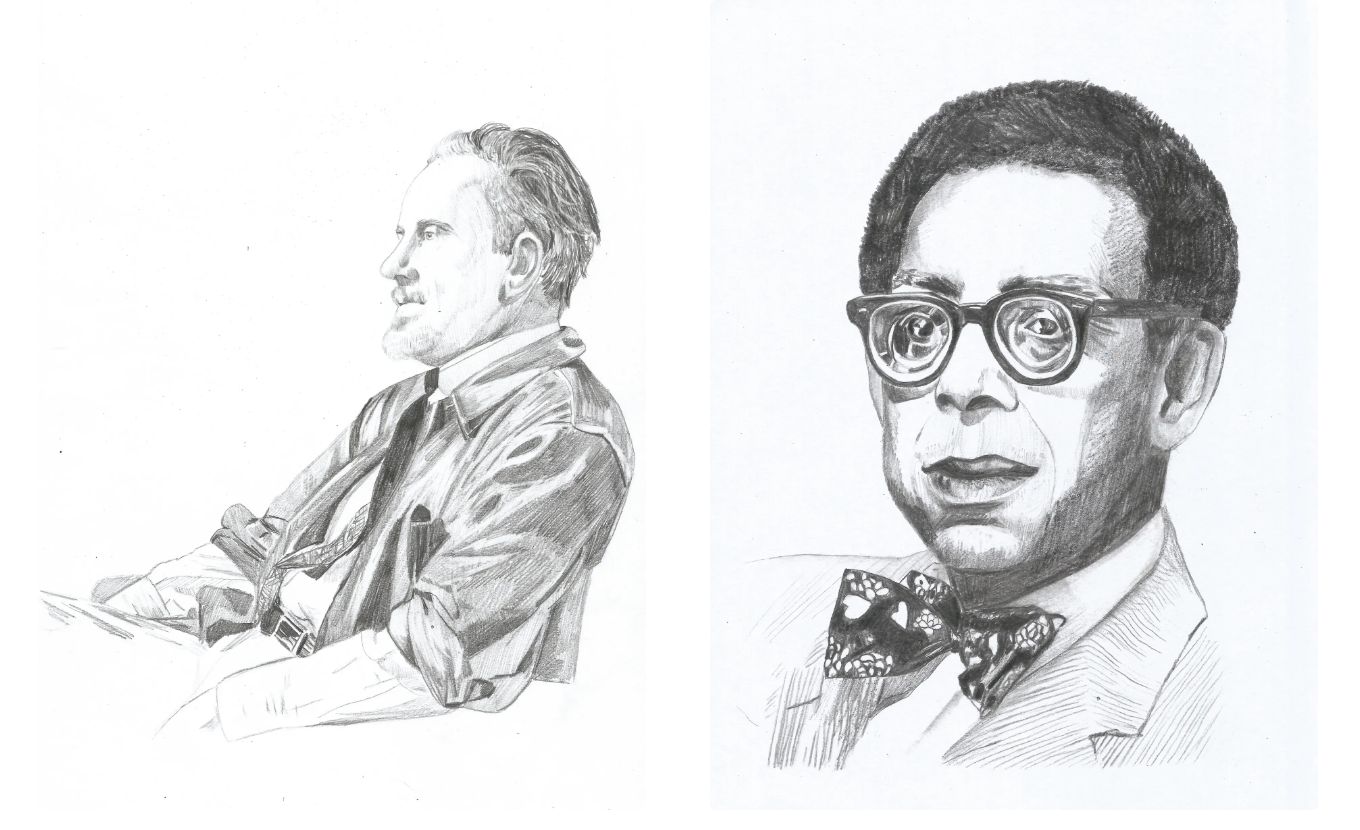

One of the Bahá’í principles promulgated with urgency by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during His travels in the United States was the elimination of racial prejudice. His address at the fourth conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) made a strong impact, for example, on sociologist and writer W.E.B. Du Bois, who published ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s speech in full in the June 1912 edition of the NAACP’s official magazine The Crisis and made Him one of the ‘Men of the Month’ in the July issue. The Bahá’í teachings on race unity also resonated forcefully with Alain LeRoy Locke—the philosophical architect of the Harlem Renaissance artistic movement, which aimed to create a body of African American writing and art comparable to the best from Europe, to celebrate and transcend the stereotypes of black American culture and encourage social integration. Locke asserted that, drawing on African American sources, black “artists could transcend the narrow conventions of Western art creating a genuinely human art.”37Willliam B. Scott and Peter M. Rutkoff. New York Modern – The Arts and the City. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1999, p.139.

Locke formally accepted the Bahá’í Faith in 1918. Five years later, making his first pilgrimage to the Bahá’í Shrines in the Holy Land, he had a profoundly affecting experience in the Shrine of the Báb and the Shrine of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, where he became “strangely convinced that the death of the greatest teachers is the release of their spirit in the world. …”38Alain Locke. “Impressions of Haifa”, The Bahá’í World Vol.3, 1928-1930. Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1980, p.280.

Through their encounters with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, then, thousands of souls in the West came into direct contact with the human embodiment of the spiritual forces released by the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, a Revelation through which, although few of them discerned it, “… the whole creation was revolutionized, and all that are in the heavens and all that are on earth were stirred to the depths.”39Bahá’u’lláh. Prayers and Meditations. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, CLXXVIII, p.295 One particular aspect of that Revelation, of which most of the artists and writers He met probably remained unaware, concerned the radical redefinition of art as being an act of worship. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described it thus to Juliet Thompson:

I rejoice to hear that thou takest pains with thine art, for in this wonderful new age, art is worship. The more thou strivest to perfect it, the closer wilt thou come to God. What bestowal could be greater than this, that one’s art should be even as the act of worshipping the Lord? That is to say, when thy fingers grasp the paintbrush, it is as if thou wert at prayer in the Temple.40Extract from a Tablet of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, www.bahai.org/r/925134802

This consecration of humanity’s creative pursuits would, as ‘Abdu’l-Bahá foresaw it, in the centuries ahead give rise to “a new art, a new architecture, fused of all the beauty of the past, but new.”41Cited in Star of the West, Vol.VI No.4, 15 May 1915, pp.30-1. Despite all of its cultural ferment and experimentation, then, the early years of the twentieth century—with its “landscape of false confidence and deep despair, of scientific enlightenment and spiritual gloom,”42Century of Light. Haifa, Bahá’í World Centre, 2001, p.7. a landscape on which the “luminous figure of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá”43Century of Light. Haifa, Bahá’í World Centre, 2001, p.7 appeared— might thus be seen merely as the first streaks of the dawn of a “new cycle of human power.”44‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.19.

The author is grateful to Debra Bricker Balkan, Hari Docherty, Dannah Edwards, Sky Glabush, Jan Jasion, Michael Karlberg, Arlette Manasseh, Anne Perry, and Nathan Rainsford for their assistance in the preparation of this essay.

Accounts of the meteoric rise, captivating claims, and mysterious public execution of the Báb—born 200 years ago in Shíráz, Iran—not only made a profound impression on the land of His birth, but also much further afield. From the distant reading rooms of Indian and English seats of learning to the salons of Paris’s Left Bank, writers and artists were enthralled by the tragedy of the Báb’s life and the appalling treatment meted out to His followers by the fanatical authorities of the time. This concise survey explores how this particular episode in humanity’s religious history resonated so strongly through the decades that followed.

Observers of the Bábí Movement

During the nineteenth century, exotic stories and images from the Orient exerted a peculiar fascination on European minds. There were those, such as the British statesman Lord Curzon, who were impelled to make the journey east, motivated by imperialist ambitions. Others, however, including the decidedly anti-imperialist Edward Granville Browne of Cambridge University, genuinely identified with the cultures they discovered and returned with a new understanding of the potentialities of the peoples they encountered. One writer has maintained that the political theme of Europe regenerating a lifeless Asia had its literary and artistic counterpoint in the thought that the less sophisticated world overseas might be able to rejuvenate a greying Europe.

1Philip Darby, Three Faces of Imperialism, Britain and American Approaches to Asia and Africa 1870–1970 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), p. 51.

The Comte de Gobineau’s Religions et Philosophies dans l’Asie Centrale (1865)—with its obvious parallels drawn between the life and martyrdom of the Báb with that of Jesus Christ—was the most influential volume in carrying the story to Western minds. The English poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold, in A Persian Passion Play, wrote that the chief purpose

of Gobineau’s book was to give a history of the career of Mirza Ali Mahommed…the founder of Bâbism, of which most people in England have at least heard the name.

2Matthew Arnold, A Persian Passion Play, Essays in Criticism (London: Macmillan, 1884), p. 668. The notion that most people in England,

in Arnold’s view, were aware of the Báb indicates how deeply His fame had penetrated into far-off societies.

An encounter with Gobineau’s text also launched Browne on his quest. His only visit to Iran in 1887–88, recounted in A Year Amongst the Persians (1893), lit a fire which…would prove inextinguishable.

3A. J. Arberry, Oriental Essays, Portraits of Seven Scholars (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960), p. 171. The memoir of his sojourn did much to familiarize English readers with the Báb, His gentleness and patience, the cruel fate which had overtaken him, and the unflinching courage wherewith he and his followers, from the greatest to the least, had endured the merciless torments inflicted upon them by their enemies.

4Edward Granville Browne, A Year Amongst the Persians (London: A. C. Black, 1950), p. 330.

A. L. M. Nicolas, a French scholar born in Iran, was also intrigued by Gobineau’s work. Nicolas’s research, encompassing translations of several of the Báb’s major Writings, additionally contributed much to raising awareness of His life and teachings: My reflections on [The Seven Proofs by the Báb] that I had translated, filled me with a kind of intoxication and I became, little by little, profoundly and uniquely a Bábí. The more I immersed myself in these reflections, the more I admired the greatness of the genius of him who, born in Shíráz, had dreamt of uplifting the Muslim world…

5A. L. M. Nicolas, cited in Moojan Momen, The Bábí and Bahá’í Religions 1844–1944: Some Contemporary Western Accounts (Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 1981), p. 37. Nicolas maintained a lifelong admiration for the Báb, concluding: Poor great Prophet, born in the heart of Persia, without any means of instruction, and who, alone in the world, encircled by enemies, succeeds by the force of his genius in creating a universal and wise religion…. I want people to admire the sublimity of the Báb, who has, moreover, paid with his life, with his blood, for the reforms he preached.

6Ibid., p. 38.

Credit: Simina Boicu

Poetic Responses in Iran

The power of the written or spoken word is given great emphasis in the Bábí and Bahá’í scriptures. The Báb Himself cited a tradition, Treasures lie hidden beneath the throne of God; the key to those treasures is the tongue of poets.

7Nabíl-i-A’ẓam (Muḥammad-i-Zarandí). The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation (Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Committee, 1932), pp. 258–59. Among the early followers of the new faith were such distinguished poets as Táhirih, Varqá, Na’ím, and ‘Andalíb.8Baydá’í’s Memoir of the Poets of the First Bahá’í Century contains biographical notes about, and examples of work by, no fewer than 134 Bábí and Bahá’í poets.

Accounts of the Bábís generated an almost immediate response from writers in Iran itself. Mírzá Habíb-i-Shírází, known as Qá’iní, one of the country’s most eminent poets, was reportedly the first to extol the Báb in his work.9Nabíl-i-A’ẓam, The Dawn-Breakers, p. 258. Footnote 1. The news of more than 300 Bábís under siege at the Shrine of Shaykh Tabársí who, despite their lack of military expertise, held off the forces of the Sháh’s army for almost a year—notably aided by an exceptionally devastating display of swordsmanship by the Báb’s first follower Mullá Ḥusayn, who was but a religious scholar—evoked the enthusiasm of poets who, in different cities of Persia, were moved to celebrate the exploits of the author of so daring an act. Their poems helped to diffuse the knowledge, and to immortalize the memory, of that mighty deed.

10Nabíl-i-A’ẓam, The Dawn-Breakers, p. 333. In the West, reports of the beleaguered Bábís were extensively covered by the press11In an ongoing study, Jan Teofil Jasion has recorded 1380 articles for the years between 1845 and 1859. By the end of December 1845, more than 50 articles had been published in newspapers throughout Britain, France and the United States of America. By 1857, newspaper reports were printed in practically every capital city in Western Europe and as far afield as Java, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, Hawaii and Canada., as well as described in travelogues by Robert Binning, Lady Sheil, and Jane Dieufloy.

Credit: Simina Boicu

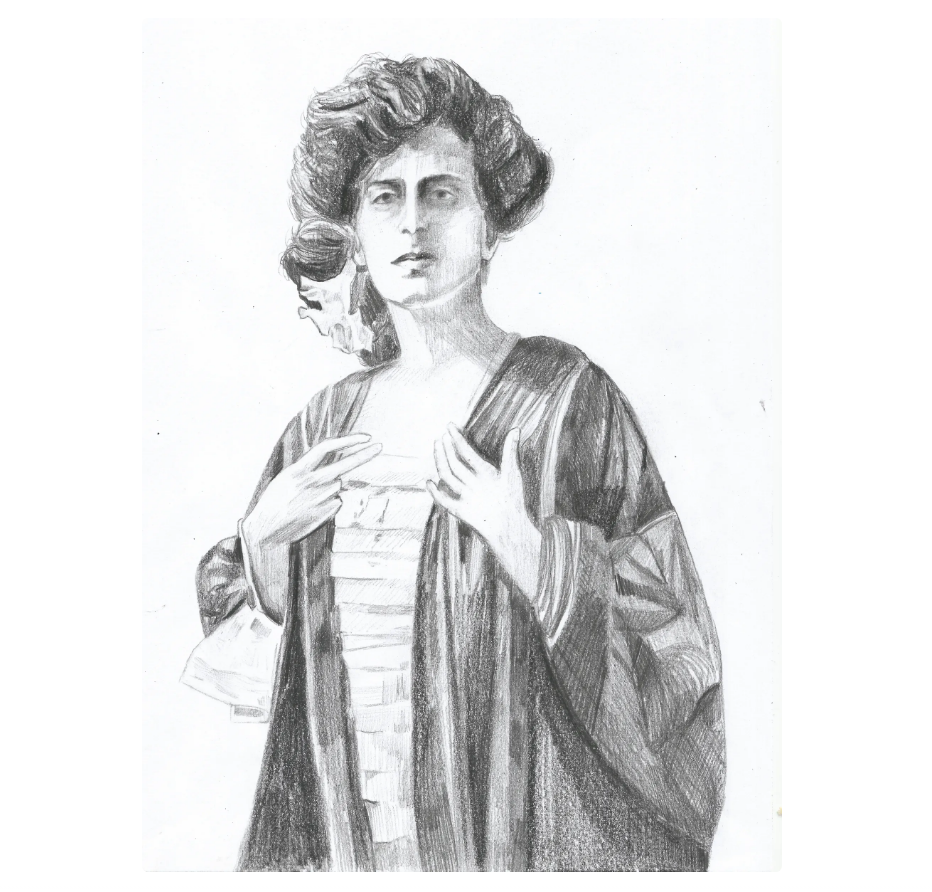

Táhirih, Qurratu’l-‘Ayn

The poet known as Táhirih, or Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, the first woman to follow the Báb, was rare among her gender at that time for her education and erudition. This ghazal, known as her signature piece, conveys her yearning devotion to the Beloved:

I would explain all my grief

Dot by dot, point by point

If heart to heart we talk

And face to face we meet.

To catch a glimpse of thee

I am wandering like a breeze

From house to house, door to door

Place to place, street to street.

In separation from thee

The blood of my heart gushes out of my eyes

In torrent after torrent, river after river

Wave after wave, stream after stream.

This afflicted heart of mine

Has woven your love

To the stuff of life

Strand by strand, thread to thread.12Táhirih, cited in Farzaneh Milani, Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers (London: I. B. Tauris, 1992).

More than any other element of the Bábí experience, it was the resolve and courage of Táhirih that seems to have excited the imagination of writers. Numerous volumes have been written about her—notably recalling her singular act of publicly removing her veil—not only in Persian, Arabic, and English but extensively in Urdu. Around 1870, after Bábís travelled to Mumbai, Táhirih’s story and poetry came to be well-known in the Indian sub-continent. The influential Punjabi-born poet, politician and philosopher Allama Muhammad Iqbal listed Táhirih among those whose songs bestow constancy to the souls because their songs derive their heat from the universe of inner-heat.

13Sabir Afaqi, Qurratu’l-’Ayn Táhirih in Urdu Literature, in Táhirih in History: Perspectives on Qurratu’l-Ayn from East and West, ed. Sabir Afaqi and Jan Teofil Jasion (Los Angeles: Kalimát Press), 2004, p. 31. In his Javid Nama (1932), Iqbal lists Táhirih as one of three martyr-guides.

Think you not Táhirih has left this world.

Rather she is present in the very conscience of her age.14Muhammad Iqbal, cited in Ibid., p. 31.

In Europe, as early as 1874, an Austrian novelist and women’s rights activist Marie von Najmajer, had written an epic poem, Gurret-ül-Eyn, believed to be the first composed in a Western language in honor of the new religion. Four years later, William Michael Rossetti mentioned both the Báb and Táhirih in a lecture given in various cities about the English poet Shelley.15William Michael Rossetti, in The Dublin University Magazine, (February/March 1878). Rossetti observed that Táhirih had an almost magical influence over large masses of the population,

16Ibid. and that the protagonists of Shelley’s poem, The Revolt of Islam, anticipate both her life and that of the Báb. In this work, Shelley seems to have captured the spirit of expectation of that time, foreseeing the imminent advent of two Divine beings:

And a voice said:

Thou must a listener be17Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt of Islam (London: C. and J. Oliver, 1818), Canto I: LVIII.

This day—two mighty Spirits now return,

Like birds of calm, from the world’s raging sea,

They pour fresh light from Hope’s immortal urn;

A tale of human power—despair not—list and learn!

Explaining the significance of a verse from Háfiz, the Báb had said, It is the immediate influence of the Holy Spirit that causes words such as these to stream from the tongue of poets the significance of which they themselves are often times unable to apprehend.

18Nabíl-i-A’ẓam, p. 259. In similar vein, Shelley had not long before declared that poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration, the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present, the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle and feel not what they inspire….

19Percy Bysshe Shelley, cited in Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, ed. Donald Reiman and Sharon Powers (New York: W. W. Norton, 1977). The creative forces that accompany the pronouncements of a Manifestation of God—or even anticipate them—thus appear to prompt the spiritual sensibilities of receptive souls.

Throughout the twentieth century, Táhirih’s fame spread further abroad. The journalist and outstanding Bahá’í teacher Martha Root, who penned a monograph about her, noted that, As I have travelled in the five continents, I have seen how her life has influenced women, and men too, throughout the world.

20Martha Root, Táhirih the Pure (Los Angeles: Kalímat Press, 1981), p. 43. A 1960 public sculpture in Baku, Azerbaijan, by Fuad Abdurrahmanov, depicting a woman casting aside her veil, is said to have been inspired by Táhirih.21See https://news.bahai.org/story/1150/ And, as recently as in 2017, Azerbaijan’s National Museum of History held a celebration recognizing Táhirih’s dedication and contribution to the advancement of women. Táhirih is held in high regard,

explained Professor Azer Jafarov of Baku State University. She influenced modern literature, raised the call for the emancipation of women, and had a deep impact on public consciousness.22Ibid.

Around the same time that Táhirih made her appearance unveiled at the Conference of Badasht in June–July 1848, the first women’s rights convention in the United States was being held at Seneca Falls, at which was launched the women’s suffrage movement in America. In the estimation of Western women, the acts of Táhirih were interpreted through the lens of their campaign for the right to vote. In Britain in 1911, the Women’s Freedom League newspaper ran a three-part article by campaigner Charlotte Despard titled, A Woman Apostle in Persia.

23Despard, Charlotte, A Woman Apostle in Persia, The Vote, Vol. IV No.101. 30 September 1911: pp.280-1. When an English Bahá’í, Mary Blomfield, petitioned King George V in person to ease the maltreatment of imprisoned suffragettes, an American Bahá’í dubbed her the Western Qurratu’l-Ayn.

24Letter from Joseph Hannen to Lady Blomfield, 7 September 1914. United States Bahá’í Archives.

Credit: Simina Boicu

Credit: Simina Boicu

The Salons of Paris

The first European novel that was set against the episode of the Báb was published in France 1891. In Un Amour au Pays de Mages, A. de Saint-Quentin—a French consular official and colleague of Gobineau’s—created a love story between a humble dervish and the daughter of a cleric in Qazvín played out amid the events of Bábí history.

Writer Jules Bois had also been so moved by the story of events in faraway Iran that, during a journey through the Holy Land, he had stopped at Mount Carmel to place flowers on the tomb of the Báb.

25Jan Teofil Jasion, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in France 1911 & 1913 (Paris: Éditions bahá’íes France, 2016), p. 189.

Writing in 1925, Bois recalled that, All Europe was stirred to pity and indignation over the martyrdom of the Báb, July 9 1850 … among the littérateurs of my generation, in the Paris of 1890 the martyrdom of the Báb was still as fresh a topic as had been the first news of his death. We wrote poems about him. Sarah Bernhardt entreated Catulle Mendès for a play on the theme of this historic tragedy …. I was asked to write a drama entitled Her Highness the Pure, dealing with the story of another illustrious martyr of the same cause—a woman, Quarratul-Ayn [sic] the Persian Joan of Arc and the leader of emancipation for women of the Orient.

26Jules Bois, cited in ibid.

Neither of the proposed plays of Mendès or Bois materialized. However, Bois did meet ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Paris on 11 November 1911, at the home of composer Hermann Bemberg, where they performed extracts from an opera they had co-written with Eustache de Lorey, titled Leïlah. Set in Shíráz, the opera contained many references to mystical Persia. It was staged in Monaco three years later.27Jan Teofil Jasion, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in France 1911 & 1913.

In 1910, the Paris-based American heiress Laura Clifford Barney—who would be active in the International Council of Women in the following decades and its representative to the League of Nations—had published her own, never performed, drama, God’s Heroes, centering on Táhirih. In its preface, Barney described her play as but a fragment of one of the most dramatic periods in history and … but a limited presentation of the most vast philosophy yet known to man.

The theatre, like all other forces may upbuild or shatter. It can be a mighty instrument for spreading ideas broadcast; and, for this reason, I believe that the wave of regeneration, which is sweeping over the world, should take form also on the stage; and am trying, therefore, in this play, to bring before the public some of the most inspiring events of our epoch.

I have, therefore, presented to the public a few episodes in the early Babi history, and only a few of the noted characters of that period: yet, even this imperfect sketch should suffice to give an idea of the vastness of the movement.28Laura Clifford Barney, God’s Heroes (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1910), p. v–vi.

Barney thought it preferable

not to portray the Báb or Bahá’u’lláh in any way for certain beings cannot be adequately impersonated.

However there is no such self-restriction in her depiction of Táhirih, who stands forth in history as an example of what the disciple of truth can accomplish despite hampering custom, and violent persecution.

29Ibid., p. viii.

At one moment in the play, Barney gives to Táhirih words that proclaim the advent of a new Revelation:

From all sides I see new life rising; the struggle between the hardened soil and the maturing seed is over. Soon, upon all things, summer will spread victorious beauty!

… even the end has a beginning for spring will again conquer, sister mine. So, when, as now, ancient faiths have become rigid in cold dead forms, a new faith germinates in the souls of men.30Ibid. p. 17.By then a devoted Bahá’í herself, Barney’s intention in presenting this history on stage was made clear to her readers at the outset:

… I hope, notwithstanding, to give you a glimpse of Eastern glory, and to awaken your interest in this great movement, the universal religion—Bahaism, which is today bringing peace and hope to expectant humanity.31Ibid. p. viii.

Credit: Simina Boicu

Credit: Simina Boicu

A Russian Stage Drama

In God Passes By, published in 1944 to mark the centenary of the Declaration of the Báb, Shoghi Effendi recorded for posterity another piece of theater:

A Russian poetess, member of the Philosophic, Oriental and Bibliological Societies of St. Petersburg, published in 1903 a drama entitled

The Báb,which a year later was played in one of the principal theatres of that city, was subsequently given publicity in London, was translated into French in Paris, and into German by the poet Fiedler, was presented again, soon after the Russian Revolution, in the Folk Theatre in Leningrad, and succeeded in arousing the genuine sympathy and interest of the renowned Tolstoy, whose eulogy of the poem was later published in the Russian press.32Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1999), p. 56.

The drama was penned by Izabella Grinevskaia, who probably first encountered the story of the Báb while researching in a St. Petersburg academic library. Several Russian scholars—including Aleksander Kazembeg, Albert Dorn, Captain A. M. Tumansky and Baron Victor Rozen—had published articles about the Báb. Published in April 1903, Grinevskaia’s play, received favorable reviews in the press, some of which quoted from it at length. One noted that the story could move a Russian as well as a Persian. It is almost strange that in our literature no-one has come to write about such a wonderful, true-to-life tragedy.

33Jan Teofil Jasion, Táhirih on the Russian Stage, in Táhirih in History, p. 233. First seen in St. Petersburg on 4 January 1904, the work conveyed its message of peace, love, tolerance, and brotherhood so successfully that, after four performances, it was banned for five years by the Tsar’s censor. It was, however, performed in Baku on 28 April and Astrakhan during the first week of December 1904. A second edition was published in 1916 and staged the following year. In 1922 the last recorded staging took place in Ashgabat in Turkmenistan.

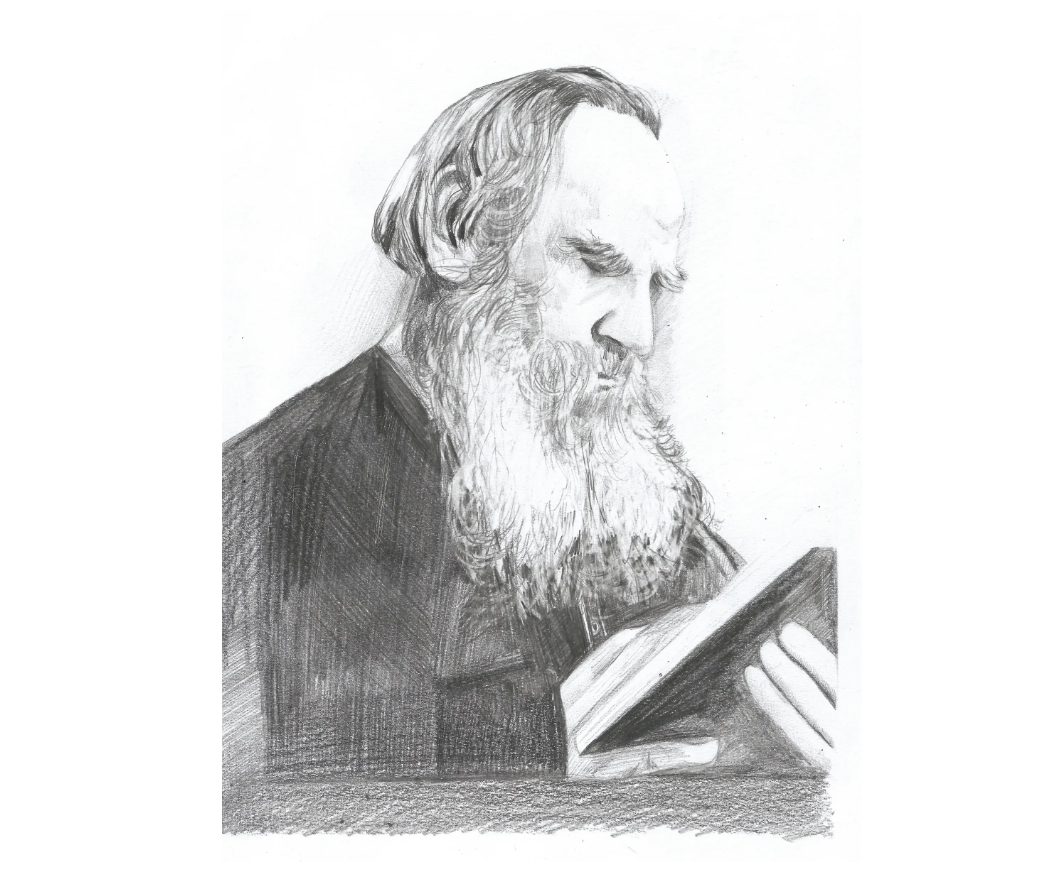

Among those who praised Grinevskaia’s play was Leo Tolstoy. A Russian journalist visiting the great author in 1903, described finding Tolstoy deeply immersed in reading the drama

and was charged by him to give his admiring appreciation to it author.

34Moojan Momen, The Bábí and Bahá’í Religions 1844–1944. p. 51. But Tolstoy’s curiosity about the Báb preceded his receiving Grinevskaia’s text. In April 1899, for example, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke paid a visit to Tolstoy with the Russian psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé and her husband, the orientalist Friedrich Carl Andreas, who had published a paper about the Bábís. Salomé later reported that Tolstoy paid little attention to her and Rilke, rather his interest was more focused on deep and invigorating discussions about the Bábí movement

with her husband.35Sasha Dehghani, Die ‘persische Jeanne d’Arc’: Zum Nachleben einer Märtyrerin,, Trajekte (Berlin) nr.15 (Oktober 2007).

In a letter to Grinevskaia, Tolstoy wrote, I have known of the Bábís for a long time and am much interested in their teachings. It seems to me that they have a great future … because they have thrown away the artificial superstructures which separate [the religions] from one another and are aiming at uniting all mankind in one religion …. And therefore, in that it educates men to brotherhood and equality and to the sacrificing of their sensual desires in God’s service, I sympathise with Bábism with all my heart.

36Moojan Momen, The Bábí and Bahá’í Religions 1844–1944. p. 55.

Credit: Simina Boicu

Credit: Simina Boicu

Response in the Twentieth Century

The Báb and His followers were thus a source of curiousity and inspiration to many writers, intrigued by His teachings and captivated by the heartbreak of their story. Later, as the Heroic Age

of Bahá’í history came to an end with the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in 1921, the Bahá’í Faith, under the direction of its Guardian, Shoghi Effendi, began to evolve into a distinct and independent, world-embracing religion, spreading to an ever-increasing number of territories. One of the reasons for Shoghi Effendi’s translation of The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation was to give newer Bahá’ís in the West both a vivid introduction to the origins of their Faith, much of which was unknown to them, and an inspirational tool to encourage their own sacrificial services in the Faith’s progress. It was also the Guardian’s hope that The Dawn-Breakers would provide artists with source material for their work: It is surely true that the spirit of these heroic souls will stir many artists to produce their best. It is such lives that in the past inspired poets and moved the brush of the painters.

37Shoghi Effendi, cited in Extracts from the Bahá’í Writings on the Subject of the Importance of the Arts in Promoting the Faith, Compilation of Compilations Prepared by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, vol. 3 (Ingleside: Bahá’í Publications Australia, 2000), pp. 27–28.

In comparison to the outpouring of those early decades of literary responses to the Báb, general works inspired by the Bábí period may have dwindled for much of the 20th century. However, following the publication of The Dawn-Breakers up until today, Bahá’ís themselves have paid homage to the Báb and the heroes of Bábí history through countless works of art, poetry, theater, film, and music, in a wide range of languages and forms of cultural expression. Two American Bahá’ís who received widespread public acclaim in the pursuit of their art and deserve brief mention here, to exemplify how The Dawn-Breakers has impacted upon creative practitioners, are the painter Mark Tobey and the poet Robert Hayden.

When Tobey was on his second pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1935, Shoghi Effendi told him that he was free to depict the early heroes of the Faith but not its Founders. Up until that time, some of the early western Bahá’ís who were painters had not attempted to illustrate any events from Bábí history, let alone attempt to convey more mystical concepts. Tobey, however, conversant with the moves toward abstraction in modernist European painting, found that his emerging visual language could be deployed not only for evoking historical events but also metaphysical ideas.

One of Tobey’s most explicit Bábí-inspired works is Movement Around a Martyr (1938). In it, he draws on his deep knowledge of renaissance art, especially the pietà figure of the martyred Christ, to depict the physical and spiritual forces that circle about a saintly figure who has been put to death. The entire image, which from a distance might be read as an all-seeing eye or maelstrom, spirals out of a small central circle, perhaps the Primal Point,

as the Báb described Himself, from which has been generated all created things.

38The Báb, Selections from the Writings of the Báb (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1982), p. 12. Swirling around the martyred figure, one lifeless arm hanging down, are mourners and worshippers, priests and helmeted guards, while more amorphous angelic figures circle above. In this work, Tobey draws an explicit parallel between the Bábí episode and the archetypal events from previous religious dispensations.

Meanwhile, in his poem, Dawnbreaker, the distinguished American poet Robert Hayden, who served from 1976 to 1978 as Consultant in Poetry to the U.S. Library of Congress, a role today known as U.S. Poet Laureate, takes as his inspiration the description of the humiliation of Hájí Sulaymán Khán, whose final punishment was to have holes gouged into his flesh into which were inserted burning candles:

Ablaze

with candles sconced

in weeping eyes

of wounds,He danced

through jeering streets

to death; oh sang

against. The drumming

mockery God’s praise.

Flames nested in

his fleshFed the

fires that consume

us now, the fire that

will save.39Robert Hayden, Angle of Ascent (New York: Liveright, 1966), p. 80.

Credit: Simina Boicu

A Continuing Story

There are two aspects to the story of the Báb—His captivating personal demeanor and the harsh treatment of His followers—that particularly seem to have sparked the imagination of writers and then later, artists. The English divine Thomas K. Cheyne recorded that the Báb’s combination of mildness and power is so rare that we have to place him in a line with super-normal men ….

40Thomas K. Cheyne, The Reconciliation of Race and Religions (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1914), p. 74. Curzon noted, that [t]ales of magnificent heroism illumine the bloodstained pages of Bábí history …. Of no small account, then, must be the tenets of a creed that can awaken in its followers so rare and beautiful a spirit of self-sacrifice.

41George N. Curzon, Persia and the Persian Question (London: Frank Cass, repr. 1966), p. 501.

To this day, the Báb continues to fascinate not only Bahá’ís around the world, but scholars of history and religion, artists, musicians, writers and dramatists. Anticipating the worldwide celebrations of both the bicentenaries of Bahá’u’lláh in 2017 and the Báb in 2019, the Universal House of Justice wrote:

At the heart of these festivities must be a concerted effort to convey a sense of what it means for humanity that these two Luminaries rose successively above the horizon of the world. Of course, this will take different forms in different contexts, extending to a myriad artistic and cultural expressions, including songs, audio-visual presentations, publications and books.42Universal House of Justice, To all National Spiritual Assemblies, 18 May 2016 (Bahá’í World Centre, 2016, mimeographed), p. 1.

The bicentenary of the Birth of the Báb in October 2019 did indeed give rise to an outpouring of artistic expressions from people on every continent, a sure reminder of the profound influence that the life and mission of the Báb is continuing to have, and will increasingly exert, on artistic expression worldwide.

Much then is still to be seen and heard, drawn and painted, spoken and sung, acted upon the stage, or captured on film—as humanity increasingly responds to the advent of a Divine Revelation and its martyred Prophet-Herald, Who fascinated contemporary commentators in the middle of the nineteenth century, and Who continues to speak to hearts and minds in the twenty-first.

Technological change is inherent to human progress. Technology, by definition, serves to augment human capacities and in so doing alters the environment in which we act. In a very real way, social reality and technology co-evolve or are co-constructed. It could be said that the industrial and information revolutions have fundamentally transformed the functioning and conception of human society. Further, the relentless pace of technical and industrial advancement over the last century has redefined the relationship between human beings and the natural world. Technology is a dominant fashioner of reality, influencing social arrangements, goals, and assumptions in a way that profoundly affects collective development, individual behavior, and the ecosystems upon which we depend. Its multifarious impacts thus must be carefully scrutinized.

A major idea emanating from current academic discourse is that technology both shapes and is shaped by social, economic, political, and cultural forces. As one writer has put it, A technology is not merely a system of machines with certain functions; rather it is an expression of a social world.

1David Nye, Technology Matters: Questions to Live With (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 47. Automobiles and road networks, power and communications systems, and the Internet are not simply technical systems but also social processes shaped by social context. Technologies can empower us but may also embody or express existing relations of power and characteristics of culture, reinforce social inequities or pathologies, or manifest ideological or strategic goals.2In relation to reinforcing patterns of social inequity, modern technological infrastructures sometimes are designed or distributed in a manner that does not benefit all populations of a society. Examples of strategic deployments of technology at the national level include large investments in space and military programs. Notably, technology, in the words of one thinker, has become a powerful vector of the acquisitive spirit

; it expresses wants or desires—and sometimes feeds them.3Dennis Goulet, Uncertain Promise: Value Conflicts in Technology Transfer (New York: New Horizons Press, 1989), 24. Our technical choices define a social reality within which the specific alternatives we think of as purposes, goals, uses, emerge.

4Andrew Feenberg, From Essentialism to Constructivism: Philosophy of Technology at the Crossroads, in Technology and the Good Life, eds. E. Higgs, A. Light, D. Strong (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 294–315. Our identity and roles in contemporary society are strongly mediated by technology; it is something we create, but it also recreates or redefines us.

The Critical Issue of Technological Choice

Technical choices shape the contours of everyday life and give real definition to modernity. These choices take place at the level of societies as well as individuals. The variety of technologies we confront—and the uncertainty about how best to use them, if at all—is daunting. Further, when we consider complex technical systems that evolve at the macro level, such as the Internet, our ability to influence the overall development and deployment of these systems seems quite limited. Nevertheless, because complex technical systems and the specific components and innovations underpinning them are socially constructed, human volition and values define their purpose and impact. We find, for example, that the intentions and values of a designer or of a corporation behind a product are embedded in ways that often are not obvious. So a simplistic notion that technology is a neutral means to freely chosen ends is not tenable. Technological advancement increasingly shapes the moral terrain on which we make decisions.5As an example, the widespread use of fetal ultrasound technology has impacted decision making regarding childbirth.

For many decades, the subject of technology has been integral to public discourse concerning processes of social and economic development. Various objectives and descriptors have been used to define the appropriateness of technology in relation to development activity: small scale, labor intensive, advanced, intermediate, indigenous, energy efficient, environmentally sensitive. 6The notion of appropriate technology, as technology of small scale that is ecologically sound and locally autonomous was championed by the economist E.F. Schumacher in his work Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, 1973. Ultimately, the appropriateness of technology is determined by the values of those creating, using, or implementing it. The appropriate technology

movement perhaps lost momentum to some degree because the role of values in guiding technological choice was not systematically explored.7Farzam Arbab, Promoting a Discourse on Science, Religion, and Development, in The Lab, The Temple and the Market: Reflections at the Intersection of Science, Religion, and Development, ed. Sharon Harper (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 2000), 149–237.

Technological development often proceeds in a manner decoupled from community values and broader questions of individual and collective purpose. In using technology, means and ends can be easily confused, and consequently community goals and requirements can be wrongly defined.8The One Laptop per Child initiative illustrates the failure to harmonize means and ends. While technical innovation allowed laptops to be produced for slightly more than $200 per device, little or no effort was made to develop pedagogical material utilizing the technology. Initial surveys from Peru, where the laptops were widely distributed in schools, indicate no improvement in educational performance by students apart from learning how to use the laptops. Critics contend that the funds used for the laptops would have been better applied to teacher training. See, The Failure of One Laptop per Child, http://hackeducation.com/2012/04/09/the-failure-of-olpc. When the link between material needs and values is ignored, the role of technology as a vehicle for upraising the human condition becomes supplanted by a process that often turns people into passive subjects rather than active users and shapers of technological instruments.

Any tool can be used productively or destructively. But the most serious consequences of technology use are often quite subtle. The rapid adoption of new technology without reflection about possible impacts has sometimes upended longstanding social and cultural patterns, where entire domains of meaning and purpose in traditional cultures are displaced.9See, for example, the case of the Skolt Lapps, Pertti J. Pelto, The Snowmobile Revolution: Technology and Social Change in the Arctic (Prospect Hts, Ill: Waveland Press, 1987). In such circumstances, technology itself becomes a bearer and even disrupter of values; it can cause individuals and communities to adapt to technology rather than use technology to extend human capability in harmony with social goals and mores. This pattern of reverse adaptation

, where technology structures and even defines the ends of human activity, is a widespread phenomenon.10An illustration of reverse adaptation is that the availability of SMS technology has transformed the nature, frequency, style and substance of personal communication. While SMS texting is undoubtedly a useful tool, in some respects it has also displaced other forms of meaningful communication or created a perceived need on the part of many for the constant sharing of trivial information. Outsourcing our personal decision-making to algorithms is another example of how many people have adapted to new technologies. Such outsourcing is, in a way, a moral choice; we may be gaining efficiency but at the cost of opening ourselves up to forces of persuasion that distort our intentions. The concept of reverse adaptation is discussed in Langdon Winner, Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-control as a Theme in Political Thought (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977), 227–29. The choices we make about technology, then, particularly when not fully evaluating their implications, may be at variance with our essential purposes, ideals, and norms. For this reason, as individuals, families, communities, and societies, we must reflect about how we design and deploy technological tools.

Technology can embed values in several other ways. It encourages that primacy be placed on efficiency, which can result in a failure to recognize negative externalities;11The classic illustration of negative externalities is the failure to take account of environmental impacts of technical innovation or industrial activity. it emphasizes a reductionist approach to problem solving, which can lead to an atomistic versus a systems approach in addressing complexity;12A reductionist approach can be found in the emphasis on recycling versus the reconsideration of systems of production and consumption. The former is obviously easier to pursue than the latter. In relation to particular social needs, there are usually different levels of technical solutions possible, with each succeeding solution having a higher degree of organizational complexity and a more formidable set of institutional and economic obstacles. An example would be the development of a mass transit system in lieu of a system relying on personal transport via automobiles. The adoption of the most optimal solution in terms of efficiency and aggregate environmental impacts—mass transit—requires active engagement and assent of the citizenry affected as it entails a different distribution of social resources. and it fosters an instrumental rationality rather than a rationality concerned with overall quality of life and meaning.13Goulet, Uncertain Promise, 17–22. What is at issue here is a general attitude fostered by a technological way of life where technology and everything it affects become instrumental—a means to an end—but the ends aren’t defined. Technology can prevent us from appreciating what is of true significance in leading a purposeful life, and thus the meaning invested in relationships and other aspects of life becomes diminished. In the end, such an orientation can result in an exaggerated reliance on technology where it is easier to diffuse technology rather than effect change in human attitudes and behavior.14An example of this technological fix mentality is the idea of geo-engineering, which involves intentional, large-scale technical manipulations of the Earth’s climate system either by reflecting sunlight or removing carbon dioxide from the air. Many scientists are concerned about the unknown risks of such approaches to alter complex natural systems. See: Technological ‘Solutions’ to Climate Change, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/geoengineering-solutions/. A facile optimism that technology alone can ameliorate or resolve pressing social challenges often only serves to exacerbate the real problems at stake in a given context.

The Role of Technology in Advancing Civilization

The concept of human betterment, of an ever-advancing civilization in which both material and spiritual well-being are continually fostered, implies a central role for science and technology and, in particular, an evolving capacity for making appropriate technological choices. Such a capacity represents an expression of human maturation. A key concept articulated in the Bahá’í teachings is that the creation, application, and diffusion of knowledge lies at the heart of social progress and development. In the latter part of the 19th century, Bahá’u’lláh urged: In this day, all must cling to whatever is the cause of the betterment of the world and the promotion of knowledge amongst its peoples.

15Bahá’u’lláh, cited in 26 November 2003 letter of the Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of Iran. And in a related passage, He affirmed: The progress of the world, the development of nations, the tranquility of peoples, and the peace of all who dwell on earth are among the principles and ordinances of God.

16Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978), 129. These and other statements in the Bahá’í writings underscore that the set of human capacities necessary for building up the material and moral fabric of collective life is derived from an expanded notion of rationality that references both mind and spirit.

While extolling the power of intellectual investigation and scientific acquisition

as a higher virtue

unique to human beings, the Bahá’í writings recognize that scientific methodologies alone cannot tell us which ideas or norms best advance a specific social objective or competence.17‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912, rev. ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 49. The knowledge required to advance social well-being must be multidimensional, encompassing not only techniques, methodologies, theories, and models but also values, ideals, qualities, attributes, intuition, and spiritual discernment. Drawing on both science and religion allows us to satisfy these diverse knowledge requirements and to identify new moral standards and avenues of learning in addressing emerging contexts of social dilemma.18The harmony of science and religion is an essential Bahá’í tenet: …faith in God and confidence in social progress are in every sense reconcilable…science and religion are the two inseparable, reciprocal systems of knowledge impelling the advancement of civilization (The Universal House of Justice, 26 November 2003). Religion is regarded as an evolutionary and civilizing phenomenon addressing knowledge at two principal levels: first, providing insight concerning human purpose, provenance, and identity; and second, informing us as social beings about the essential parameters of social interaction and the very nature of the social order, particularly how it should be constructed to reflect principles of fairness, empathy, and cooperation. As an essential expression of reality, religion is not to be dismissed as an atavistic phenomenon irrelevant to the processes of social advancement. Rather, it is a primary force shaping human consciousness, ensuring that humanity’s distinctive potentialities, particularly its rational powers, are constructively channeled. This sheds light on the full range of capabilities that must be employed in understanding, developing, evaluating, and using technology. In essence, technology is a magnifier of human intent and capacity, and consequently, it cannot become a substitute for human judgment or action.

The term technology

derives from the Greek techne,

which is translated as craft

or art

. In this sense, technology is the branch of human inquiry and activity relating to craftsmanship, techniques, and practices; to innovation and provision of objects; and to systems based on such objects. While the term technology

is not explicitly used by Bahá’u’lláh or the Báb, we do find references to the arts and sciences,

craftsmanship,

and invention.

Bahá’u’lláh wrote: Arts, crafts and sciences uplift the world of being, and are conducive to its exaltation. Knowledge is as wings to man’s life, and a ladder for his ascent.

19Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), 26. The knowledge referred to here in the original Arabic is ‘ilm. Two principal types of knowledge are alluded to by Bahá’u’lláh: ‘ilm, referring to knowledge gained by the use of reason, investigation and sensory perception, and irfán, referring to spiritual insight, awareness and inner knowledge. That irfán and ‘ilm are deeply connected is underscored by Bahá’u’lláh throughout His writings. For example, He states: The source of all learning (‘ulúm, plural of ‘ilm) is the knowledge of God (irfán Allah). Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, 159. And in a prayer, the Báb wrote: I yield praise unto Thee, O Lord our God, for the bounty of having called into being the realm of creation and invention.