When calamity strikes, questions concerning the distribution of material resources often follow. The Great Depression gave birth to the New Deal, a series of sweeping government programs and reforms in the United States aimed at immediate economic relief for the “forgotten man.”1Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speech on the “forgotten man” on the eve of his announcing the New Deal. Accessed online from the Pepperdine School of Public Policy (https://bit.ly/3f387Xy) on 9 June 2020. The world wars saw the expansion and consolidation of the modern welfare state via a wave of nationalizations and other measures designed to provide a “cradle-to-grave” safety net in areas like health, education, housing, and retirement benefits. For today’s generation, both the Great Recession of 2008 and the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 exposed great social and economic inequalities and reinvigorated debate as to the causes and consequences of the unequal distribution of economic resources and opportunities. Both crises spurred governments to levels of unprecedented social spending, hundreds of billions to prevent the failure of banks in 2008/9 and hundreds more billions—even trillions—to prevent the grave consequences of mass unemployment in 2020. Yet, notwithstanding renewed interest in the topic and bold government action, and despite the fact that humanity is currently enjoying unprecedented levels of material prosperity, the distribution of material resources—of wealth and income in particular—has grown ever more unequal. In fact, according to one social historian, inequality has, since the Stone Age, always been rising, and only four forces—the “Four Horsemen of Leveling”—have ever managed to lower it: pandemics, mass warfare, revolution, and state collapse. 2Scheidel, Walter, The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2018). Today, 20 percent of the global income is owned by the richest 1 percent of the world’s population whereas the poorest 50 percent own just 9 percent.3Based on administrative and other data from the World Inequality Database accessed at wid.world The choice thus appears to be either to come to terms with ever rising levels of inequality or hope for disaster. Must it really be so?

The Bahá’í teachings explain that the inordinate disparity between rich and poor is a “source of acute suffering” which “keeps the world in a state of instability.”4Universal House of Justice, letter of October 1985 to the peoples of the world, titled “The Promise of World Peace”. Available at www.bahai.org/r/267204466 Furthermore, the negative consequences of extreme inequality have been documented by scholars of various disciplines. They include social and political instability5Alberto Alesina and Roberto Perotti, “Income Distribution, Political Instability and Investment,” European Economic Review 40, no.6 (1996):1203-1228. as well as threats to environmental sustainability.6See, for example, the annual reports of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. At the individual level, inequality can lead to shorter, unhealthier, and unhappier lives, including increases in teenage pregnancy, violence, and obesity.7Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010).

Of course, it is one thing to agree that inequality—at least in its extreme forms—is bad. For a religious person, it can be all too easy to fall into the trap of moralizing, on the basis of lofty spiritual principle, perceived or actual inequalities. The far more difficult task is to articulate a coherent conception of what sort of equality is good. This is a challenging question, one with a long philosophical tradition that focuses on such things as equality of opportunity, equality of outcomes, fair versus unfair inequality, and more. The purpose of this article is to stimulate reflection on these matters by setting out a number of principles contained in the Bahá’í teachings related to distributional issues and by connecting these principles to today’s economic conditions. The Bahá’í concept of social change envisions the transformation of human society to be the aggregate of two other interlocking transformations: that of the individual and that in the structures of society. The article, therefore, discusses principles intended to stimulate reflection on both the collective and individual levels and highlights, where possible, potential mechanisms—public policy and political participation, to name just two examples—through which these principles might find practical expression.

In attempting to correlate Bahá’í principles to current economic conditions, this article presents a number of facts concerning the global distribution of income, facts drawn from measures collected by leading academic economists. The interested reader is invited to consult the technical appendix for a more thorough description of what these data measure and the caveats associated with them.

The Bahá’í Teachings on (In)Equality

The distribution called for in the Bahá’í Writings is not to be understood as absolute equality. In this respect, Shoghi Effendi writes that “[s]ocial inequality is the inevitable outcome of the natural inequality of man. Human beings are different in ability and should, therefore, be different in their social and economic standing.”8Shoghi Effendi. Directives of the Guardian No. 55. Available at https://reference.bahai.org/en/t/se/DG/dg-55.html ‘Abdu’l-Bahá elaborates this idea, explaining that people differ in their capacities and should thus “receive wages that would correspond to their varying capacities and resources.”9Ibid According to the principle of divine justice, perfect equality is not just undesirable but unattainable. In this connection, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explains that by divine justice,

[i]t is not meant that all will be equal, for inequality in degree and capacity is a property of nature. Necessarily there will be rich people and also those who will be in want of their livelihood, but in the aggregate community there will be equalization and readjustment of values and interests.10‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/640654326

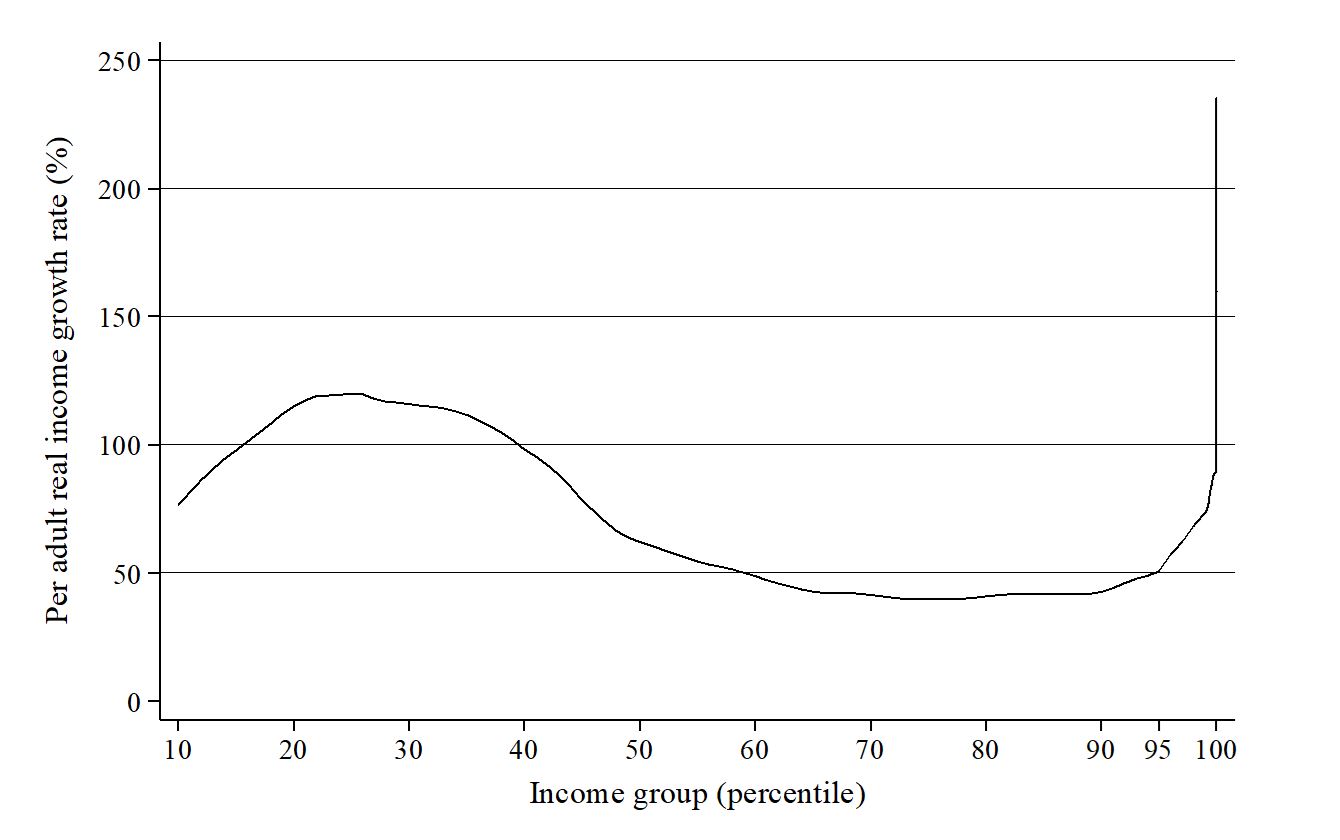

What matters more than equality in outcomes is an equal chance to succeed, “justness of opportunity for all,”11Ibid. Available at www.bahai.org/r/305820706 according to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Today, however, social mobility is as restricted as income is concentrated, even when one considers the efforts of some nations, most notably China and India, to lift many millions out of extreme poverty. This is made clear in Figure 1. On the horizontal axis, the world population is divided into one hundred groups of equal population size and sorted in ascending order from left to right, according to each group’s income level. The vertical axis shows the total income growth of an individual in each group between 1980 and 2016. As shown, individuals in the top 1 percent saw their incomes rise by more than 100 percent over the time period whereas individuals in the top 0.01 percent experienced income growth of more than 200 percent. Calculations by the authors who collected the data indicate that, while those in the bottom 50 percent did experience some income growth, they collectively claimed just 12 percent of total income growth from 1980 to 2016. 12Alvaredo, Facundo, Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman. 2018. “The Elephant Curve of Global Inequality and Growth.” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 103-08. Available at https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/pandp.20181073 Those in the top 1 percent, by contrast, claimed 27 percent over the same period. The figure is a powerful illustration of how sharply the incomes of the richest segments of society have grown, especially when compared to increases in other groups.

How Much is Too Much?

According to the Bahá’í teachings, the solution to many of the economic problems that afflict humanity appears rather simple: moderation. That is, while some degree of inequality is natural, the Bahá’í teachings unequivocally call for the elimination of the extremes of wealth and poverty. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá speaks of the “equal opportunity of the means of existence” whereby “a rich man is able to live in his palace surrounded by luxury and the greatest comfort” just as a “poor man be able to have the necessaries of life.”13‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Paris Talks. Available at www.bahai.org/r/095377521 The “readjustment in the economic conditions of mankind” that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá envisions will be such that

in the future there will not be the abnormally rich nor the abject poor. The rich will enjoy the privilege of this new economic condition as well as the poor, for owing to certain provisions and restrictions they will not be able to accumulate so much as to be burdened by its management, while the poor will be relieved from the stress of want and misery.14‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/841208804

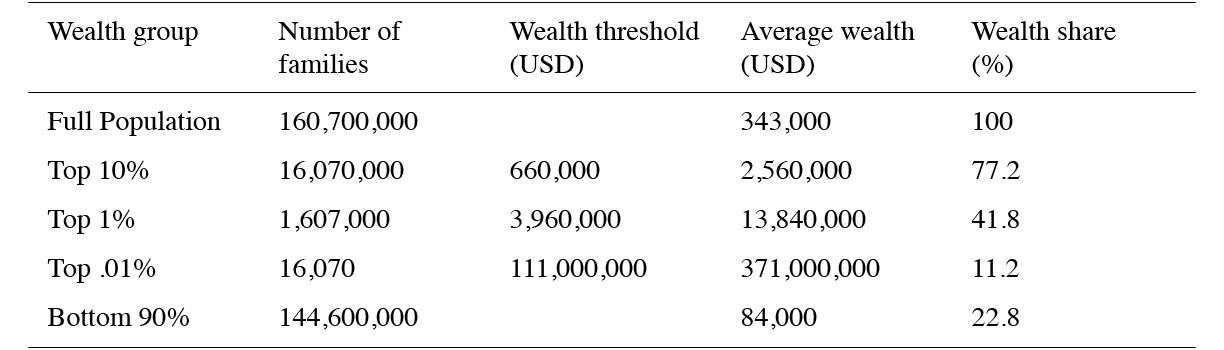

Though seemingly simple, striking the right balance in wealth distribution has proven immensely difficult. Table 1 provides one example of wealth distribution in the richest country of the world, the United States. The table shows how much wealth a family requires to belong to different percentiles of the wealth distribution. The top 1 percent of earners in America consists of just over 1.5 million families. To belong to this group, a family requires $3.9 million; the average wealth of all families in this group stands at $13.8 million. To be counted among the 16,070 families in the top 0.01 percent of the distribution requires a staggering $111 million of wealth. In contrast, there are nearly 145 million families in the bottom 90 percent of the distribution. These families each have, on average, $84,000 in wealth.15Though related, wealth and income are not the same. Wealth typically is more concentrated than income. As the authors of the paper from which the data was taken state: “The top 0.1% wealth share is about as large as the top 1% income share in 2012: by that metric, wealth is ten times more concentrated than income.” Saez, Emmanuel and Zucman, Gabriel. 2016. Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), pp.519-578.

To demonize wealth is not the point. Quite the contrary. The Bahá’í teachings not only prohibit asceticism but regard wealth as “praiseworthy in the highest degree” provided it is (a) acquired through honest means and (b) used to advance philanthropic purposes.16‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Secret of Divine Civilization. Available at www.bahai.org/r/753844522 Although the Teachings warn against luxury and excess, Bahá’u’lláh enjoins us to use our wealth as a means to achieve worthy ends. “The best of men,” He writes, “are they that earn a livelihood by their calling and spend upon themselves and upon their kindred for the love of God, the Lord of all worlds.”17Bahá’u’lláh. The Hidden Words from the Persian No. 82. Available at www.bahai.org/r/002944255 Aside from the prohibition against asceticism, Bahá’ís are also discouraged from adopting austere lifestyles. In response to a letter received on the subject, Bahá’u’lláh writes the following:

Thou hast written that they have pledged themselves to observe maximum austerity in their lives with a view to forwarding the remainder of their income to His exalted presence. This matter was mentioned at His holy court. He said: Let them act with moderation and not impose hardship upon themselves. We would like them both to enjoy a life that is well-pleasing.18Bahá’u’lláh quoted in the compilation entitled Huqúqulláh — The Right of God Selection No. 19. Available at https://bit.ly/3fpYphM

Addressing Inequality from the Top and Bottom

The issue, instead, appears to be one of economic justice based on our interconnectedness. One wonders, for example, to what extent extreme wealth causes, and indeed is a consequence of, extreme poverty and whether policies that allow for the hyper-concentration of wealth simultaneously make it easier for the disadvantaged to fall into destitution. “The welfare of any segment of humanity,” the Universal House of Justice writes, “is inextricably bound up with the welfare of the whole. Humanity’s collective life suffers when any one group thinks of its own well-being in isolation from that of its neighbors.”19Universal House of Justice, letter of 1 March 2017 to the Bahá’ís of the World regarding economic life. Available at www.bahai.org/r/934375828 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, moreover, explains that “[w]ealth is most commendable, provided the entire population is wealthy.”20‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Secret of Divine Civilization. Available at www.bahai.org/r/753844522

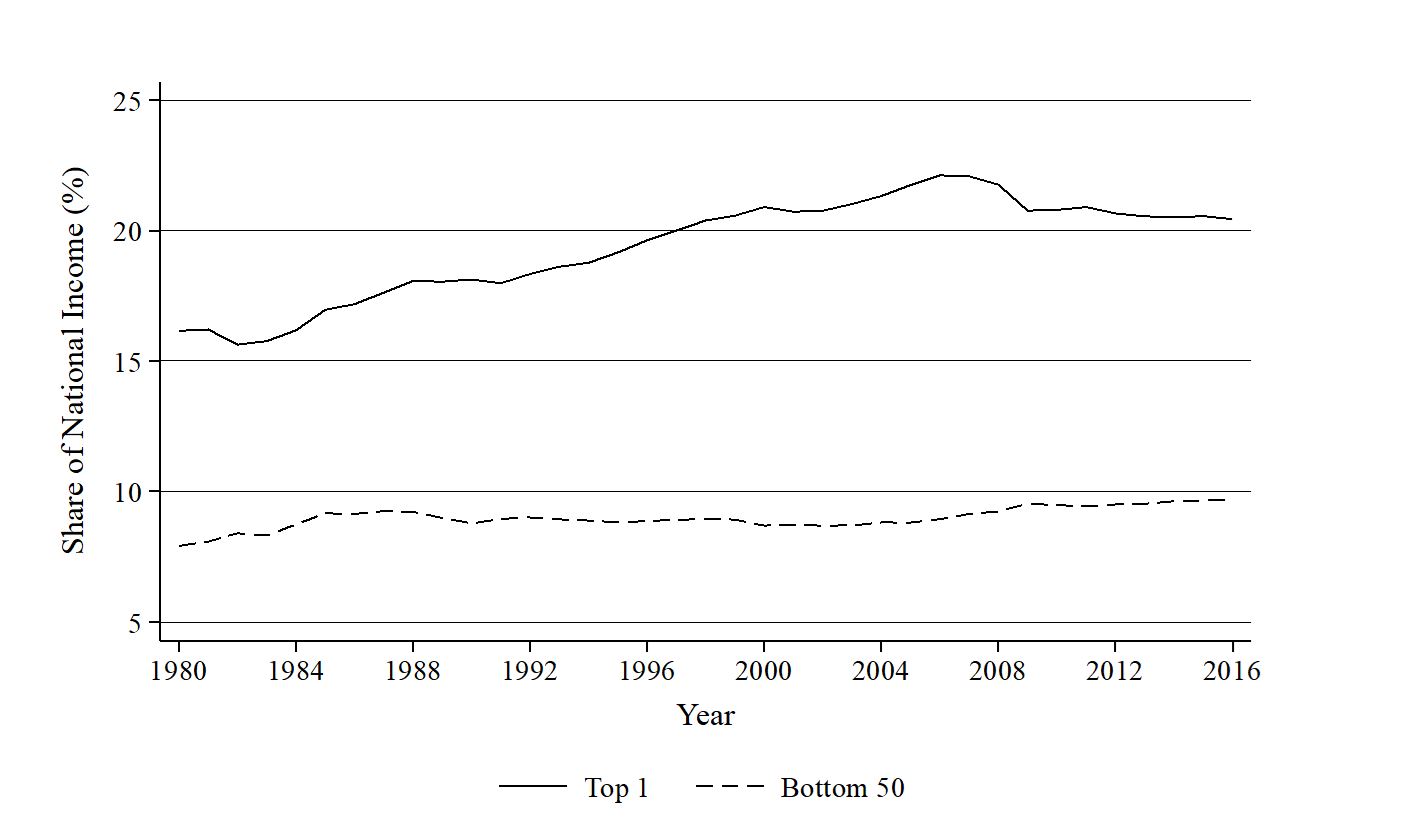

Given the interconnected nature of the human family, efforts to realize a more just distribution of economic resources must be addressed from both the top—by, for example, regulating and limiting the hyper-concentrated accumulation of wealth through taxation and other measures21In The Promulgation of Universal Peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá speaks about the elimination of trusts, for example. Available at Available at www.bahai.org/r/196674493 —and the bottom—via transfers and strong social spending. Calls to unleash economic growth, on the assumption that it automatically translates into an equitable distribution of resources, are unfounded. This is made evident in Figure 2 which plots trends in the share of national income accruing to the top 1 percent and the bottom 50 percent of earners in the global income distribution.

The above figure demonstrates two facts: differences in (a) levels and (b) trends between top and bottom earners. With respect to levels, those in the top 1 percent of the income distribution earn, on average, about 10 percentage points more of national income than those in the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution (19 percent for the top 1 percent compared to 9 percent for the bottom 50 percent). In addition, top earners are trending at three times the rate. Between 1980 and 2016, those in the top 1 percent of the income distribution increased their share of national income by 4.4 percentage points, from 16 percent to 20.4 percent. For those in the bottom 50 percent, their share of national income increased by just 1.5 percentage points over the same time period. More than anything, the figure casts significant doubt on the assertion—often used as justification for tax cuts for the wealthy—that rises in income at the very top provide wealth, opportunity, and incentives for those at the bottom. While a rising tide may lift all boats, structuring the economy so as to allow wealth to funnel upwards does not. In brief, economic justice requires that the rules that regulate the economy are fair and not tilted to the benefit of a particular segment of society to reinforce its enrichment.

Collective Choice: The Power of Public Policy

‘Abdu’l-Bahá asserts that “there is need of an equalization and apportionment by which all may possess the comforts and privileges of life is evident.” “The remedy,” He explains, “must be legislative readjustment of conditions.”22‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/904155405

The power of public policy to shape societies cannot be overstated. Indeed, the mechanism through which society expresses its values as regards to social order is public policy. Economies, however, unlike the natural universe, are not prone to description through a set of universal, immutable laws. They are social constructs. Who participates in them and what values these participants hold matter. This is made evident by three examples.

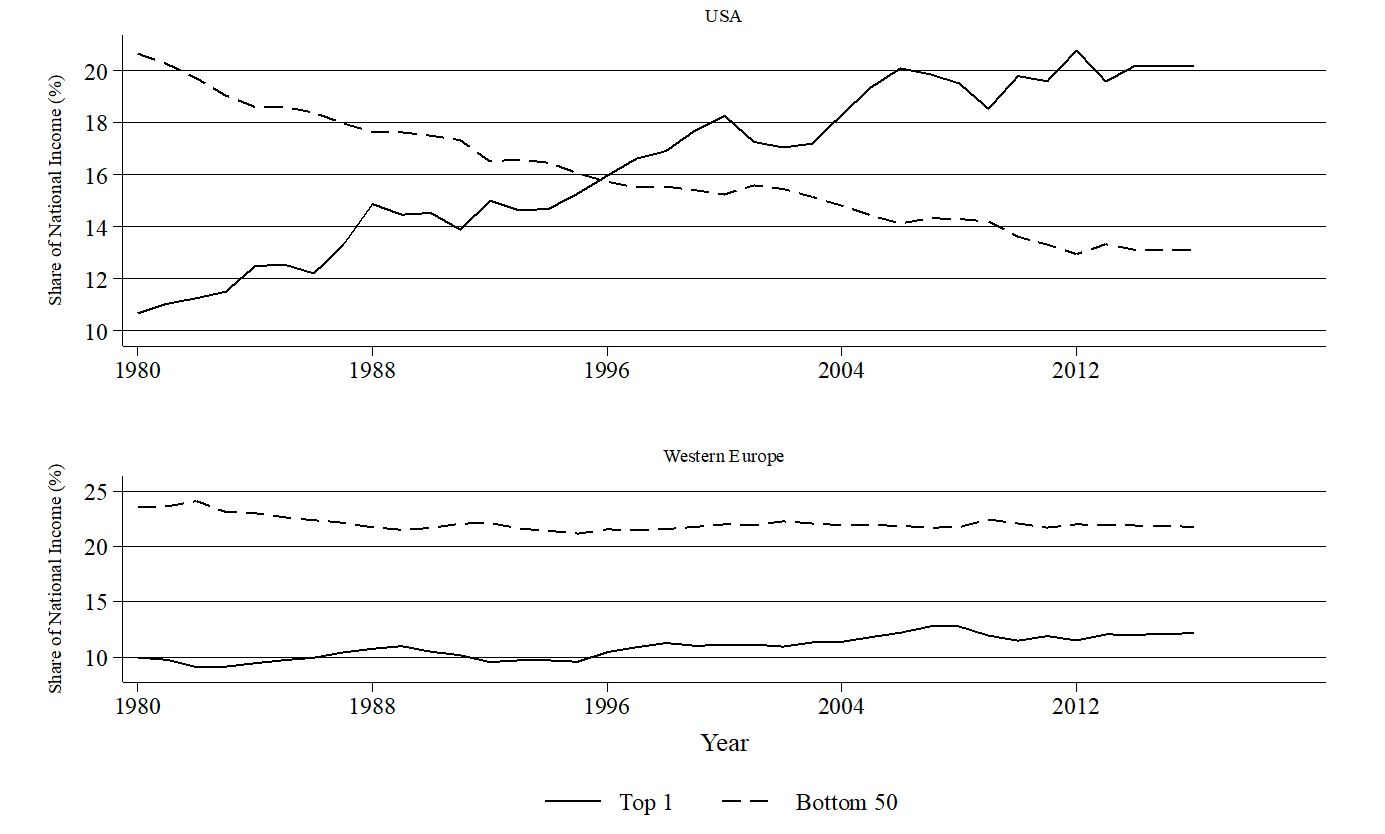

First, Figure 3 shows the same trends as in Figure 2 but disaggregated to two regions/countries: the United States and Western Europe. The trends are remarkable, as is the contrast between them. In Western Europe, those in the bottom 50 percent of the distribution have claimed, on average, 12 percentage points more of national income than those in the top 1 percent, a complete reversal of the global averages. What is more is that the trends have been relatively stable in the 35 years leading to 2016. In the United States, by contrast, the two series are trending at high rates and in the exact opposite direction. Whereas those in the top 1 percent have seen their share of national income increase from 10 to 20 percent from 1980 to 2016, those in the bottom 50 percent have seen theirs decline from 20 to 13 percent in the same time period. Given that Western Europe and the United States enjoy relatively similar levels of material prosperity, political stability, exposure to globalization, and technological advancement, the trends highlight the role that national policies, institutions, and voter preferences play in shaping the distribution of income.

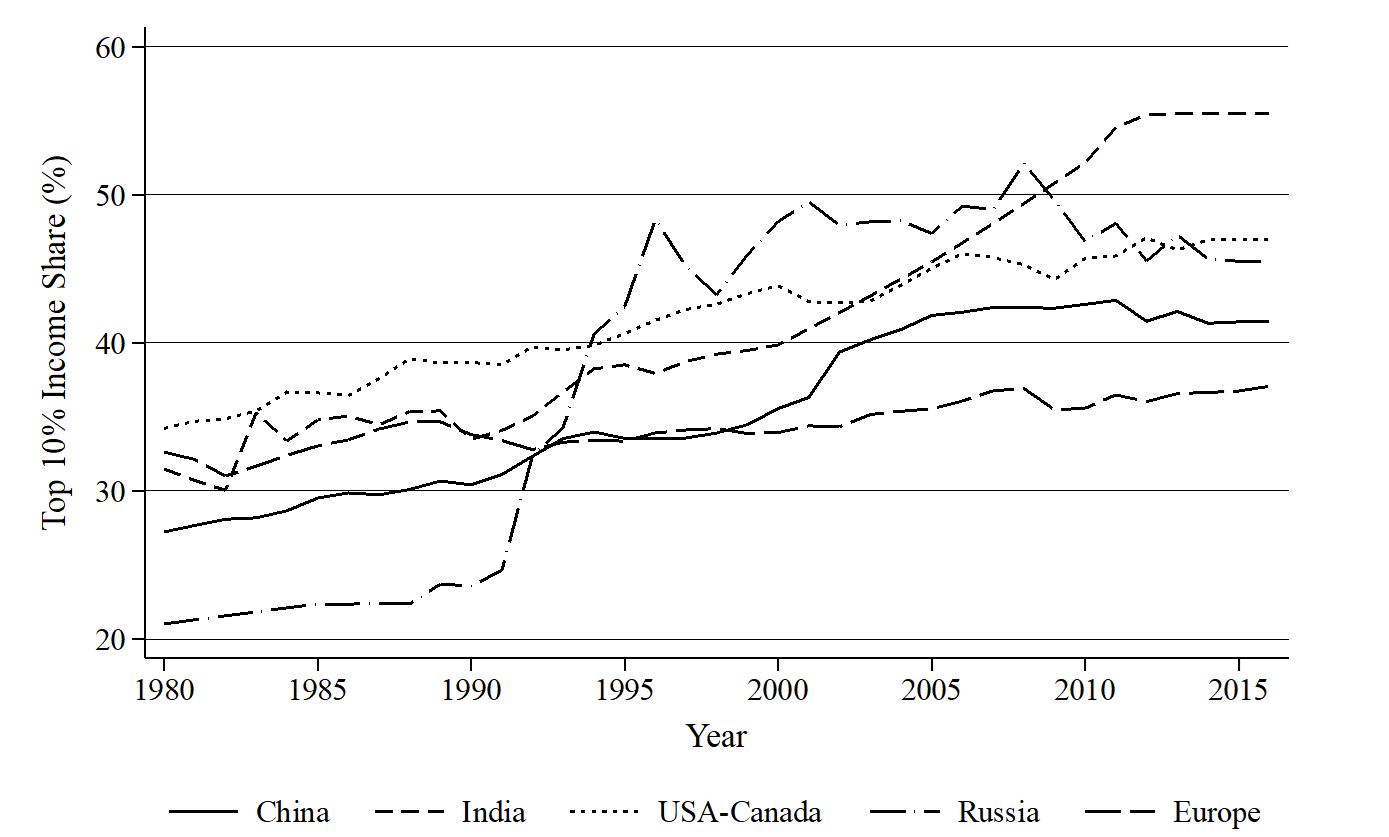

Second, Figure A.1 in the Appendix shows the evolution of the top 10 percent in a sample of six countries around the world between 1980 and 2016. As shown, there is a steady increase in all countries, though the increases occur at different rates. In India, for example, those in the top 10 percent of the income distribution claimed 24 percentage points more of national income in 2016 (55 percent) as compared to 1980 (31 percent). In the USA and Canada, by contrast, the rise for those in the top 10 percent over the same time period was 13 percentage points; in Europe, the increase was just 4.4 percentage points. The different rates at which top earners accumulate across different countries again underscores the importance of national policies and institutions in shaping the distribution of income. Rising inequality, in other words, is not just an inevitable outcome of impersonal market forces at work.

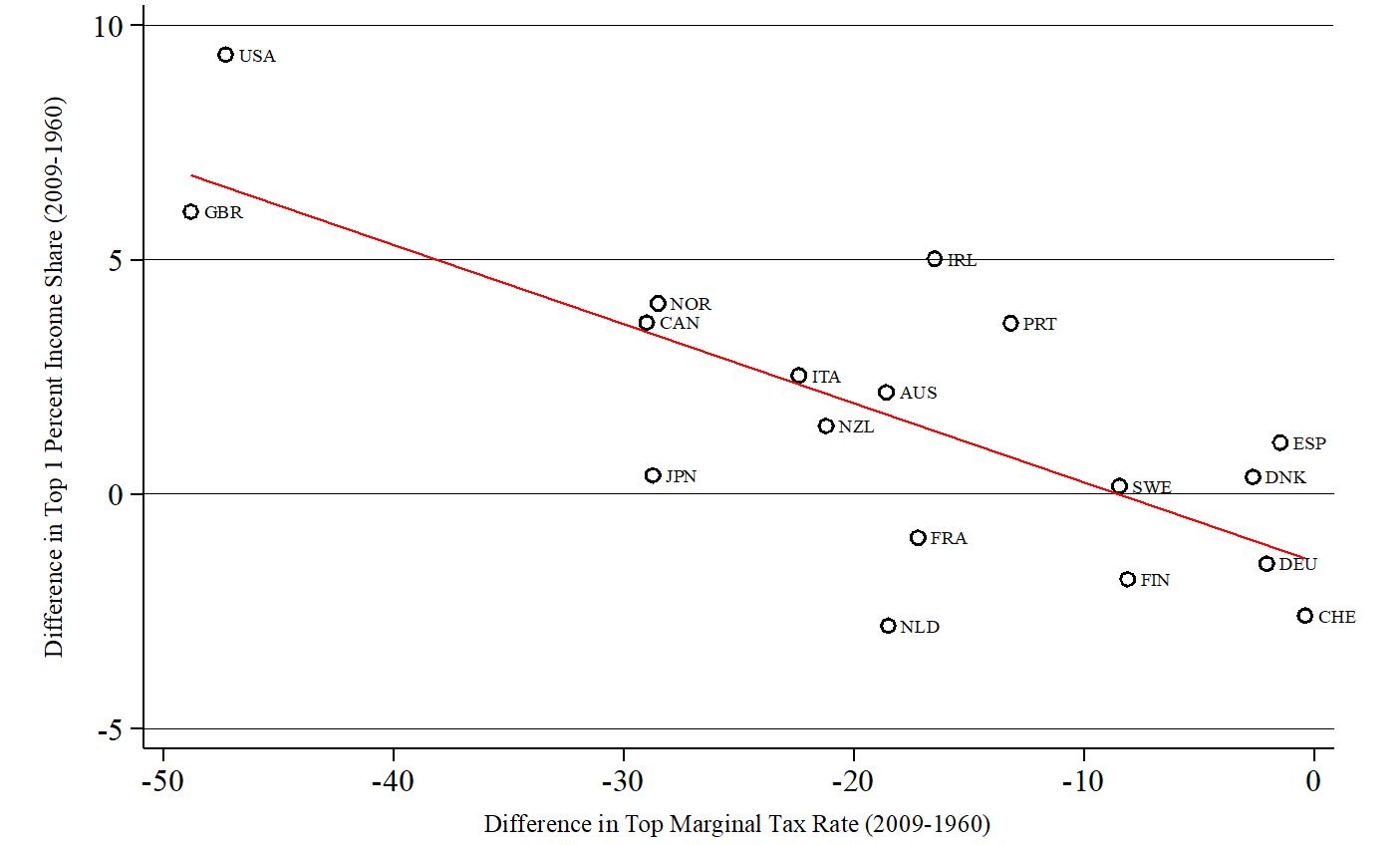

Finally, Figure 4 provides another example of the strong impact public policy plays in shaping economic outcomes. It plots the changes, in percentage points, in the share of pre-tax national income accruing to the top 1 percent against the change (in percentage points) in the top marginal tax rate between 1960 and 2009 in a sample of 18 OECD countries. As shown, the countries with the steepest declines in top marginal tax rates have also experienced the steepest increases in the share of national income accruing to the top 1 percent. What is more, there “is no statistically significant relationship between the decrease in top marginal tax rates and the rate of productivity growth in the developed countries since 1980.”23Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press. pp. 510 In other words, lowering the tax rate of the wealthiest segments of society has had a strong, positive effect on their earnings without stimulating growth and productivity in the wider economy.

Like the other examples in this section, Figure 4 highlights how public policy can shape the economy to achieve a certain social outcome. Different policies will invariably lead to different outcomes. The hyper-concentration of wealth is thus a choice, not an inevitability. “There is no justification,” the House of Justice explains, “for continuing to perpetuate structures, rules, and systems that manifestly fail to serve the interests of all peoples. The teachings of the Faith leave no room for doubt: there is an inherent moral dimension to the generation, distribution, and utilization of wealth and resources.”24Universal House of Justice, letter of 1 March 2017 to the Bahá’ís of the World regarding economic life. Available at www.bahai.org/r/934375828 Put simply, the moral dimension of the generation, distribution and utilization of material resources implies that policy be designed to serve the interests of all people. Finding novel ways to justify policies that serve the economic interests of the few at the expense of the many is a tendency of humanity’s collective childhood, not its coming of age.

Collective Choice: The Power of Participation

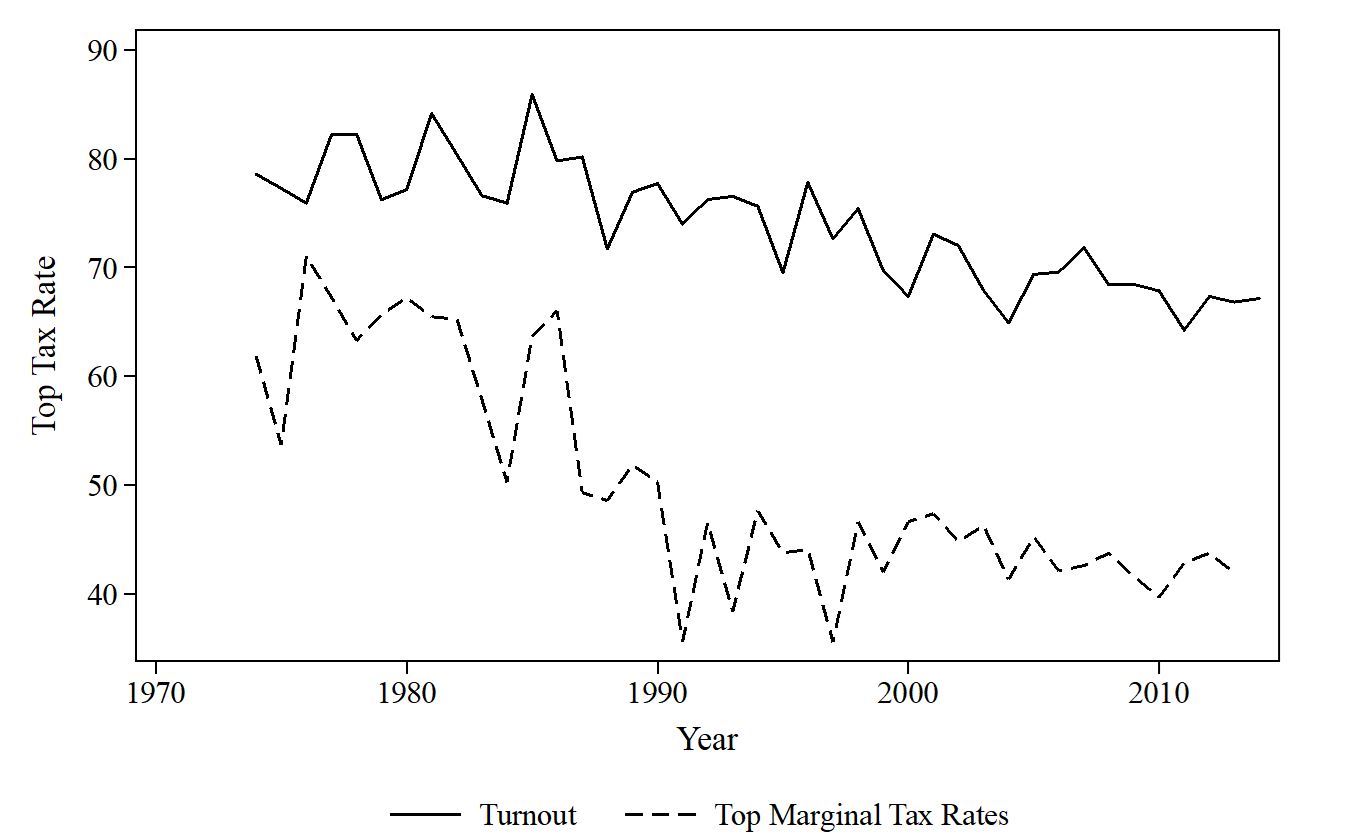

Ensuring that public policy reflects the interests of all people requires participation. “A key characteristic of democracy,” writes Robert Dahl, a prominent political theorist, “is the continuing responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens, considered as political equals.”25Robert A. Dahl, Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971). One of the ways that governments respond to the preferences of its citizens is by paying attention to who votes. In recent decades, however, the share of people turning out to vote has decreased in many countries. And in many cases, the decline in voting is marked along class lines. Indeed, a number of studies have shown that those who vote are typically better educated, wealthier, and more informed politically than those who abstain, and these very characteristics have been shown to correlate strongly with certain preferences for redistribution, or the lack of it.26See, for example, Valentino Larcinese, “Voting over Redistribution and the Size of the Welfare State: The Role of Turnout,” Political Studies 55 (2007):568-585; Martin Gilens, “Inequality and Democratic Responsiveness,” Public Opinion Quarterly 69, no. 5(2005): 778-796; Benjamen I. Page et al, “Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans,” Perspectives on Politics 11, no. 1(2013): 51-73.

Falling rates of voter turnout, therefore, imply that the preferences of wealthy individuals are over-represented in relation to those of the population in general, which places less pressure on public policy for redistribution. In line with this thinking, academic scholarship has shown a rather robust relationship between the rate of voter turnout and the size of government spending on redistributive policies. These studies have found that higher turnout across countries leads, among other things, to higher top marginal tax rates,27Navid Sabet, “Turning Out for Redistribution: The Effect of Voter Turnout on Top Marginal Tax Rates,” Munich Discussion Paper no. 2016-13 (University of Munich, Department of Economics, 2016). Accessed 22 August 2020: https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/72625/ welfare expenditure and the political leaning of the party in power,28Alexander M. Hicks and Duane H. Swank, “Politics, Institutions, and Welfare Spending in Industrialised Democracies, 1960-1982,” American Political Science Review 86, no. 3 (1992): 658–674. and social spending in non-welfare categories such as education and health.29Peter H. Lindert, “What Limits Social Spending?” Explorations in Economic History 33 (1996):1–34. Within countries, various episodes of voter enfranchisement have been studied to show that governments systematically target resources to serve the economic interests of the newly enfranchised group. This appears to be true of African Americans,30Elizabeth U. Cascio and Ebonya L. Washington, “Valuing the Vote: The Redistribution of Voting Rights and State Funds Following the Voting Rights Act of 1965,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no.1(2914):379-433. women,31Grant Miller, “Women’s Suffrage, Political Responsiveness, and Child Survival in American History,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 123, no.3 (2008):1287–1327. lesser educated citizens,32Thomas Fujiwara, “Voting Technology, Political Responsiveness, and Infant Health: Evidence from Brazil,” Econometrica 83, no. 2 (2015): 423–464. and undocumented migrants.33Navid Sabet and Christoph Winter, 2019. “Legal Status and Local Spending: The Distributional Consequences of the 1986 IRCA,” CESifo Working Paper Series No. 7611, CESifo. Accessed 22 August 2020: https://www.cesifo.org/DocDL/cesifo1_wp7611_0.pdf

Put plainly, if those with lower incomes participate less in political processes, then public economic policy is likely to be less responsive to their preferences. Measures to broaden participation in political processes can help ensure that markets are structured to serve the interests of all people. In this respect, it is interesting to note that less than 100 years ago, many industrialized nations had tax rates well over 70 percent. Germany, for example, experienced top marginal tax rates as high as 75 percent in the early 1950s and a 90 percent rate in the late 1940s. 34Piketty, Capital, 2014 The United Kingdom set top income tax rates as high as 98 percent in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, while the United States levied a 91 percent tax on top incomes in the 1950s and 1960s and then relaxed the rate to 70 percent or more throughout the 1970s.35Ibid Figure A.2 in the Appendix shows trends in voter turnout and top marginal tax rates in the countries that comprise the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). As shown, higher turnout in the 70s corresponded with much higher top marginal tax rates. Since that time, both series have trended significantly downward.

Of course, the foregoing discussion highlights the important role of political participation—electoral participation in particular—in shaping economic outcomes. It goes without saying that this is but one form of participation that we may be interested in. Moreover, the empirical evidence cited demonstrates the correlation between rates of electoral participation and various economic outcomes. In addition to strengthening participation in this way, raising the quality of participation is another issue to consider. Perhaps one of the strongest measures to take in this regard is improving education and access to knowledge. In this respect, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explains that “[p]ublic opinion must be directed toward whatever is worthy of this day”. Accordingly, He explains: “It is therefore urgent that beneficial articles and books be written, clearly and definitely establishing what the present-day requirements of the people are, and what will conduce to the happiness and advancement of society” and these thoughts “should be published and spread throughout the nation, so that at least the leaders among the people should become, to some degree, awakened, and arise to exert themselves along those lines which will lead to their abiding honor”. “The publication of high thoughts” He moreover explains “is the dynamic power in the arteries of life; it is the very soul of the world.”36‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Secret of Divine Civilization. Available at www.bahai.org/r/226587004

Profit Sharing

To the extent that ends ought to be consistent with means, achieving moderate social and economic outcomes must be achieved through moderate policy. In this respect, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá calls on the governments of the world to unite and form an assembly to deliberate on the distribution of resources and to enact regulations in such a way that “neither the capitalists suffer from enormous losses nor the laborers become needy. In the utmost moderation they should make the law.”37‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/052723345

It is preferable, then, that some measure of moderation be achieved, and by moderation is meant the enactment of such laws and regulations as would prevent the unwarranted concentration of wealth in the hands of the few and satisfy the essential needs of the many. For instance, the factory owners reap a fortune every day, but the wage the poor workers are paid cannot even meet their daily needs: This is most unfair, and assuredly no just man can accept it. Therefore, laws and regulations should be enacted which would grant the workers both a daily wage and a share in a fourth or fifth of the profits of the factory in accordance with its means, or which would have the workers equitably share in some other way in the profits with the owners. For the capital and the management come from the latter and the toil and labour from the former. The workers could either be granted a wage that adequately meets their daily needs, as well as a right to a share in the revenues of the factory when they are injured, incapacitated, or unable to work, or else a wage could be set that allows the workers to both satisfy their daily needs and save a little for times of weakness and incapacity.38‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Some Answered Questions, No. 78. Available at www.bahai.org/r/389724725

One potential measure outlined here is profit sharing—sharing between a fourth to a fifth of the profits of the factory “in accordance with its means”—as part of a nation’s “laws and regulations.” Another is setting wages according to need, not just market prices; a subtle but significant change from today’s practices.

Collective Wealth

Other proposals ‘Abdu’l-Bahá offers include progressive taxation based on needs. He writes, for example, that

[e]ach person in the community whose income is equal to his individual producing capacity shall be exempt from taxation. But if his income is greater than his needs, he must pay a tax until an adjustment is effected. That is to say, a man’s capacity for production and his needs will be equalized and reconciled through taxation. If his production exceeds he will pay a tax; if his necessities exceed his production he shall receive an amount sufficient to equalize or adjust. Therefore, taxation will be proportionate to capacity and production and there will be no poor in the community.39‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace, p. 217. In other writings ‘Abdu’l-Bahá provides examples where, depending on an individual’s surplus, they may be taxed anywhere between 25 and 50 percent. Available at www.bahai.org/r/828752876

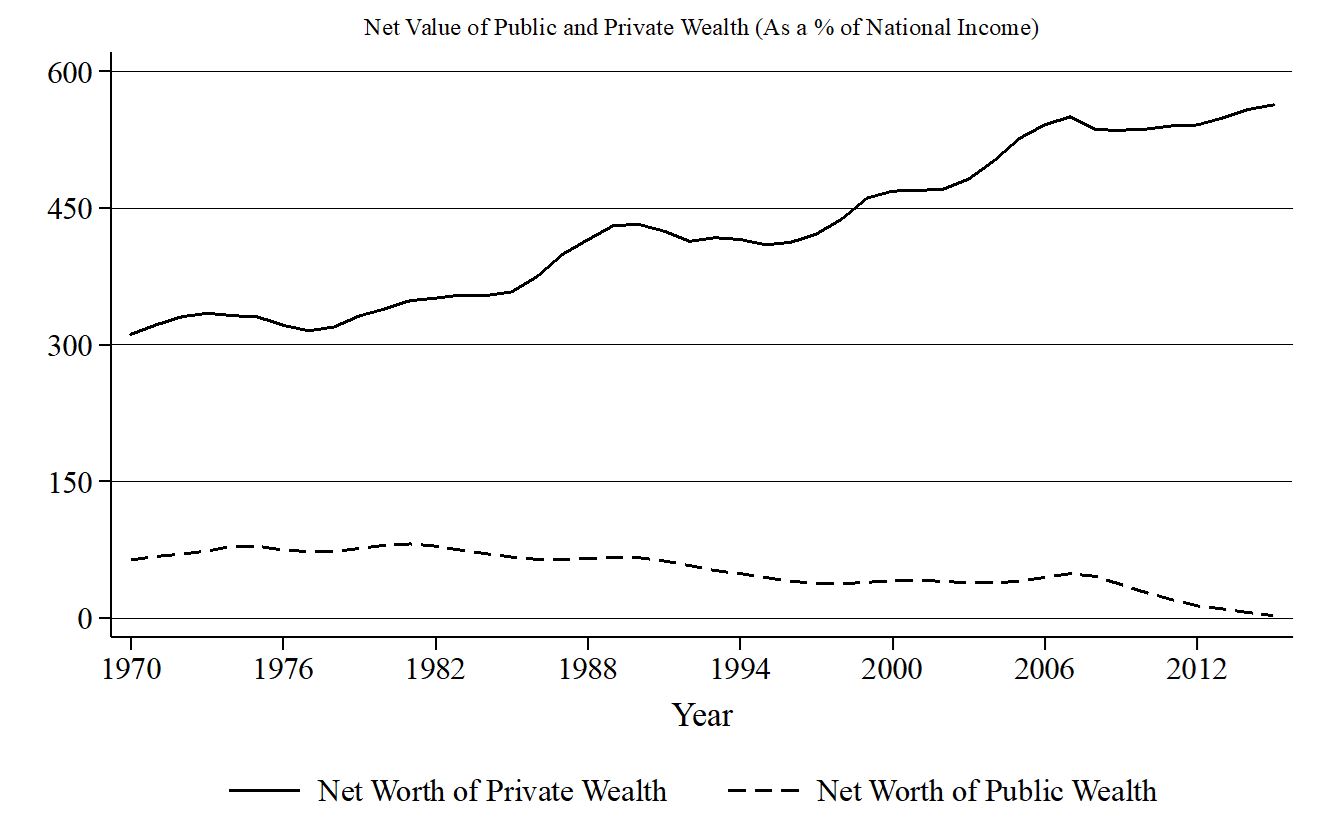

Today, the majority of government revenues come from individual income taxes. Interestingly, in many countries, individuals have become richer while their governments have become poorer, as reflected in the net share of public and private capital held in each country (see, for example, Figure A.3 in the Appendix). To illustrate, consider the case of Germany. In 2015, the value of net public wealth (i.e., public capital) stood at 18 percent of national income. Private wealth, on the other hand, stood at over 420 percent of national income. By way of comparison, net public wealth in the United States in 2015 was -17 percent of national income, whereas private capital stood at over 500 percent.

This unequal ownership of capital—between private citizens and the state—may also explain rising inequality. In the 1980s, there were demonstrably large transfers of public to private wealth in nearly all countries. While national wealth has substantially increased, public wealth is now negative or close to zero in rich countries. Arguably this limits the ability of governments to tackle inequality. But more than that, it eats away at things like trust and social cohesion, so essential for a stable, prosperous society. When governments, that is, consistently take more from the poor than the rich, establishing and maintaining trust in public institutions becomes increasingly difficult.

The idea is not to punish wealth but to avoid the privatization—and hence polarization—of society, whereby only those with means can afford things like quality education and healthcare. The solution called for by a number of progressive economists includes a combination of policies aimed at, on the one hand, redistribution—for example, a steeply progressive tax not just on income but on wealth and effective corporate taxation strategies to curb tax avoidance—and, on the other, pre-distribution—that is, sufficient social spending to fund a modern, social welfare state with strong investments in education and healthcare to ensure everyone has an equal chance to succeed, as well as labor market regulations that do not allow for extreme wage dispersion.40For an example in the case of the United States, see Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2019).

Aspiring as Individuals Towards a Just Economy

The market economy has, in some respects, led to wonders in human coordination. That products, the constituent parts of which may come from a variety of different countries, can be delivered to one’s doorstep within days of ordering speaks to humanity’s capacity to innovate, create, and manage higher and higher levels of complexity. Such systems, although not without serious shortcomings, merit praise, not condemnation.

At the same time, many societies are organized so as to place economic growth as the central, dominating process of human life, to the point where all other processes are subordinated to it. Organizing society to serve the needs of the economy has had significant consequences for the way we understand human nature and human relationships. Achieving a deeply just social order will thus require more than just a few cosmetic changes—as vital and essential as they may be—to the way taxes are set and who receives which transfers. It also requires a fundamental examination of the ways in which market-embedded societies have influenced our understanding of human nature and our relationships—to one another and to the market—and an effort to reconstruct those relationships in light of spiritual principle.

Consumption

Consider the example of consumption. It is no secret that one of the deliberate goals of the global development effort of the 20th century was to push the developing nations of the world through a “set” of development “stages” culminating in the “age of high mass-consumption.”41Walt W. Rostow, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990). To sustain high levels of economic growth, great attention was given to ensuring that people turn to the market not just to satisfy needs but to fulfill wants. Influential economists, many of whom provided the intellectual support for major policy reform aimed at economic expansion, were explicit in their intentions to stimulate and expand people’s wants. The idea put forward at the time was that “wants are limited because the goods one knows about and can use are limited.”42Arthur Lewis, The Theory of Economic Growth (1955; Reprinted in 2003 by Routledge). Increase people’s wants, and their consumption—and hence demand for economic goods and services—will increase. Thus, the key for societies, therefore, lay in spreading knowledge of new goods among the populace since this was “the key to the expansion of wants.”43Ibid

For those concerned about a viable, sustainable future, the line of demarcation between needs and wants is a profound one, with serious implications for the economy. Satisfying the needs of an individual whose main purpose in life is to serve others in an effort to contribute to a more just society will call for a very different set of economic arrangements than those required to satisfy individuals who, influenced by sources of propaganda and advertisement, are led to discover new “needs” every day. The words of Bahá’u’lláh leave a penetrating influence:

O Son of Man! Thou dost wish for gold and I desire thy freedom from it. Thou thinkest thyself rich in its possession, and I recognize thy wealth in thy sanctity therefrom. By My life! This is My knowledge, and that is thy fancy; how can My way accord with thine?44Bahá’u’lláh. The Hidden Words from the Arabic No. 56. Available at www.bahai.org/r/748392247

Of course, the discussion of needs and wants necessarily comes with a number of caveats. For one, there is no universal set of needs applicable to all people at all times: Different people have different needs and indeed the same person will likely have different needs at different points in his or her life. For another, needs can also be considered in terms of their quantity and degree. One may require a suit for his or her profession. But how many suits are needed? And does one need a suit with a designer brand when a suit of similar quality and look without the label would suffice just as well? Of course, this is not to say that only legitimate needs are good and that all forms of desire are bad. It is just that without reflection on our consumption habits, we may be prone to encourage the worst tendencies of the market while foregoing opportunities to refine our higher nature. More than anything, the issue appears to be one of awareness: How conscious are we of what we consume and why? Ultimately, the House of Justice explains, “Managing one’s financial affairs in accordance with spiritual principles is an indispensable dimension of a life lived coherently. It is a matter of conscience, a way in which commitment to the betterment of the world is translated into practice.”45Universal House of Justice, letter of 29 December 2015 to the Conference of the Continental Board of Counsellors. Available at www.bahai.org/r/521400059

Human Compassion and Love

Evaluating the worth of a person by his or her economic status is another tendency that a society focused on acquisition promotes, and a tendency we would need to do away with in an effort to build an economy based on spiritual principle. “To view the worth of an individual,” the House of Justice clearly writes, “chiefly in terms of how much one can accumulate and how many goods one can consume relative to others is wholly alien to Bahá’í thought.”46Universal House of Justice, letter of 1 March 2017 to the Bahá’ís of the World regarding economic life. Available at www.bahai.org/r/476802933 This has implications for our attitude towards the poor. “No deed of man is greater before God,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá writes, “than helping the poor. Each one of you must have great consideration for the poor and render them assistance.”47‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/305820706 In addition to legal codes and regulations, then, those with means are called upon to be “merciful to the poor” and to contribute “from willing hearts to their needs without being forced or compelled to do so.”48Ibid. Available at www.bahai.org/r/904155405 Achieving this level of compassion requires love. He writes, for example:

Hearts must be so cemented together, love must become so dominant that the rich shall most willingly extend assistance to the poor and take steps to establish these economic adjustments permanently. If it is accomplished in this way, it will be most praiseworthy because then it will be for the sake of God and in the pathway of His service. For example, it will be as if the rich inhabitants of a city should say, “It is neither just nor lawful that we should possess great wealth while there is abject poverty in this community,” and then willingly give their wealth to the poor, retaining only as much as will enable them to live comfortably.49Ibid. Available at www.bahai.org/r/978851230

Introducing such ideas into contemporary discourse may seem difficult. In trying, it is helpful to note that these ideals have received intellectual support for many years. In his Theory of Moral Sentiments, written in 1759, Adam Smith draws on these elements of our nature in an effort to offer a sweeping account of moral philosophy that underpinned much of his economic thinking. For example, he writes that “[m]an naturally desires, not only to be loved, but to be lovely; or to be that thing which is the natural and proper object of love.” Moreover, he explains:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it.50Smith, Adam. 1759. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. 2010 Penguin Classics edition.

These ideals are also supported by empirical evidence. One influential economic article notes, for example, that

[a]lmost all economic models assume that all people are exclusively pursuing their material self-interest and do not care about “social” goals per se. This may be true for some (maybe many) people, but it is certainly not true for everybody. By now we have substantial evidence suggesting that fairness motives affect the behavior of many people.51Ernest Fehr and Klaus M. Schmidt, “A Theory of Fairness, Competition and Cooperation,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 114, no.3 (1999):817-868.

In recent decades, the economics of altruism have flourished, and there are many examples that show human beings to be more than the calculating, self-interested being that initial, primitive models suggest. There is evidence that demonstrates we are motivated as much by considerations of fairness and cooperation as we are by selfish ones. Being motivated by considerations of love and compassion will surely be added to the list.

As it relates to the distribution of economic resources, then, an economy based on the principles of justice and equity does not object to efforts to improve material conditions or to increase wealth and income. The objection is that such efforts have come at the expense of an expanded view of human nature that includes a spiritual dimension. Markets, this article has argued, are social constructs. The policies we choose matter. The candidates we elect matter. The goods and services we consume matter. The understanding we have of human nature and of the purpose of our existence matters. All these things have significant cumulative effects on the way that markets, and their outcomes, are structured. “Every choice a Bahá’í makes,” the House of Justice clearly explains, “leaves a trace, and the moral duty to lead a coherent life demands that one’s economic decisions be in accordance with lofty ideals.”52Universal House of Justice, letter of 1 March 2017 to the Bahá’ís of the World regarding economic life. Available at www.bahai.org/r/904550633 Through moderate yet bold legislative adjustment and a spiritually awakened populace, it is possible for material and spiritual prosperity to coexist.

It is often assumed that income inequality is caused by the operation of impersonal market forces, the like of which include wages, advances in technology, increased market competition, and the rising returns of individual investments in education. While there is little doubt about the pivotal role economic forces play in generating and distributing wealth, economic rationale alone cannot explain income disparities that are everywhere occurring as a result of the gross accumulation of wealth by those at the very top of the income distribution. Fostering economic justice requires a spirit of charity, to be sure, based on an understanding of our inherent interconnectedness as a human family. But it also requires strong institutional arrangements that prevent people from over-accumulating at the top and under-accumulating at the bottom.

TECHNICAL APPENDIX

Additional Figures

This figure plots the share of pre-tax national income claimed by adults (equal-split series where income is split equally between adults who belong to the same couple or household based on administrative records) in the top 10 percent of national income distribution. Pre-tax national income is the sum of all pre-tax personal income from labor and capital before taxes but after pension, unemployment insurance, and other social insurance schemes. Based on data from wid.world.

Measuring Income and Wealth

This article has used three types of inequality rather interchangeably, namely, economic inequality, income inequality, and wealth inequality. Although the basic conclusions of the article are insensitive to which measure is used, the interested reader may be curious to know more precise definitions for each.

Economic Inequality vs. Income Inequality

It is acknowledged that income inequality is but one of many inequalities that we may be concerned about, including non-economic ones. Even within the economic realm, economic inequality is a rather broad concept referring to non-income related inequalities. Amartya Sen makes an argument to distinguish between narrow forms of inequality based on income and broader forms of economic inequality. As he puts it:

The argument for shifting our attention from income inequality to economic inequality relates to the presence of causal influences on individual well-being and freedom that are economic in nature but that are not captured by the simple statistics of incomes and commodity holdings.53Amartya K. Sen, “From Income Inequality to Economic Inequality,” Southern Economic Journal 64, no. 2 (1997):383-401.

He lists influences such as environmental diversities, variations in social climate, personal heterogeneity (disabilities, illness etc.), and distributions within households as examples of how economic inequality is broader than simple measures of disparity in income. Although related, the facts and figures discussed in this article are more concerned with wealth and income inequality rather than broader measures of economic inequality.

Income and Wealth: What is the Difference?

Most of the facts and figures under discussion are related to income inequality, which includes the component parts of income from labor (i.e., wages), income derived from wealth (i.e., profits and capital gains), and inequality derived from expenditure on consumption. There are two issues to bear in mind with this measure. First, the income figures presented measure pre-taxincome. In some sense, then, the figures present inequality as generated by the market economy but do not reflect the efforts of states, via measures like taxes and transfers, to correct for inequalities. A second issue is that taxable income does not enjoy a uniform definition. Different nations count taxable income slightly differently—indeed, the same country may count it differently at different points in its development—and no adjustments are made to account for any potential discrepancies.

There is also the issue of wealth inequality, which typically refers to inequality in things like land-holdings and property, financial assets, capital stock, and so on. Wealth is harder to measure than income, and thus most discussions on inequality refer to income inequality. Nonetheless, wealth and income are highly correlated and wealth is usually much more concentrated than income. As Piketty explains:

There are important differences between income and wealth inequality dynamics, however. First, we stress that wealth concentration is always much higher than income concentration. The top decile wealth share typically falls in the 60 to 90% range, whereas the top decile income share is in the 30% to 50% range. Even more striking, the bottom 50% wealth share is always less than 5%, whereas the bottom 50% income share generally falls in the 20 to 30% range. The bottom half of the population hardly owns any wealth, but it does earn appreciable income: On average, members of the bottom half of the population (wealth-wise) own less than one-tenth of the average wealth, while members of the bottom half of the population (income-wise) earn about half the average income.

In sum, the concentration of capital ownership is always extreme, so that the very notion of capital is fairly abstract for large segments—if not the majority—of the population. The inequality of labor income can be high, but it is usually much less extreme. It is also less controversial, partly because it is viewed as more merit-based. Whether this is justified is a highly complex and debated issue to which we later return.54Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “Inequality in the Long Run,” Science 34, no.6168 (2014): 838-843.

Measuring Income and Wealth

There are, by and large, two predominant methods to measure the distribution of income. The first relies on an index called the gini coefficient and is derived primarily through household survey information. The second, arguably more reliable measure which has recently been championed by a number of prominent economists, relies on a combination of data from national income and wealth accounts, fiscal data coming from taxes on income and, to an extent, household income and wealth surveys. All of the facts and figures presented here are based on this measure of distribution—unless otherwise stated—and are taken from the World Inequality Database which can be accessed at wid.world.