The Bahá’í writings describe the modern period as an age of transition toward a future world civilization that manifests the oneness and essential diversity of humankind. The “world’s equilibrium,” Bahá’u’lláh writes, has been “upset” by the “vibrating influence” of “this most great, this new World Order.” The Universal House of Justice further elaborates upon Bahá’u’lláh’s remarks by likening these disruptive transformations to the period of adolescence: “Humanity, it is the firm conviction of every follower of Bahá’u’lláh, is approaching today the crowning stage in a millennia-long process which has brought it from its collective infancy to the threshold of maturity—a stage that will witness the unification of the human race. Not unlike the individual who passes through the unsettled yet promising period of adolescence, during which latent powers and capacities come to light, humankind as a whole is in the midst of an unprecedented transition. Behind so much of the turbulence and commotion of contemporary life are the fits and starts of a humanity struggling to come of age. Widely accepted practices and conventions, cherished attitudes and habits, are one by one being rendered obsolete, as the imperatives of maturity begin to assert themselves.”1Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, www.bahai.org/r/581649978; Universal House of Justice, “A Letter to the Bahá’ís of Iran, Dated 2 March, 2013,” www.bahai.org/r/394327546. This essay explores the idea of modernity as an age of transition as presented in the Bahá’í writings.2Other sources develop resonant accounts of modernity as an age of transition. See, for example, such mid-twentieth century works as: Lewis Mumford, The Transformation of Man (New York: Harper & Row, 1956); Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History, trans. Michael Bullock (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1953); Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Human Phenomenon, ed. Sarah Appleton-Weber (Eastbourne, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 1999). Or, more contemporaneously: Robert Wright, Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny, n.d.; Prasenjit Duara, The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian Traditions and a Sustainable Future (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Joseph Chan, Confucian Perfectionism: A Political Philosophy for Modern Times (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

The origins of the modern age of transition

The modern age of transition begins as a movement out of the medieval order of civilization, some prominent expressions of which include the Song Dynasty of imperial China (960-1279 CE), the Hindu-Islamicate society of Mughal India (1526-1857 CE), the Mali Empire of West Africa (1235-1670 CE), and orthodox-Christian Byzantium (286-1453 CE). Each of these medieval societies relied upon a material substrate of village-based agrarian activity. These agrarian villages were, in turn, ruled by a cadre of urban elites whose authority was thought to hierarchically descend from the divinely sanctioned powers of a single emperor or king. Both social layers were, in turn, embedded in a common religious-metaphysical system, among which those associated with Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Neo-Confucianism were concurrently preeminent. And although by around 1250 CE, certain Old World elites had established a meaningful web of Afro-Eurasian interconnections, each medieval society still largely continued to consider itself civilizationally autonomous.3For useful descriptions of the medieval order of civilization see: Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-135 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 103–117; Rethinking World History: Essays on Europe, Islam, and World History, ed. Edmund III Burke (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 44–71; Mumford, The Transformation of Man, 81–94.

Precisely how and when the medieval order began to decline is a matter of scholarly debate. What is clear, however, is that the upheavals of the “long nineteenth century”—from roughly 1770 to 1920—inaugurated the modern age of transition by firmly uprooting the foundations of medieval civilization. The advent of industrial manufacturing undermined the agrarian, village-based substrate of medieval life by unleashing the explosive powers of fossil fuels, mechanical technology, and megapolitan urbanization. Populist revolutions in the United States (1765-1791), France (1789-1799), and Haiti (1791-1804) stimulated novel vectors of political change that would, by the middle of the twentieth century, help topple most of the world’s great monarchical empires. The spreading influence of secular and materialistic ideologies disrupted the taken-for-granted authority of long-established ecclesiastical institutions and religious creeds. And a succession of pathbreaking transportation and communication technologies, including the steamboat (1803), the locomotive (1804), electric telegraphy (1844), the petrol automobile (1886), broadcast radio (1896), and the airplane (1903), overwhelmed medieval notions of civilizational autonomy by dramatically interlinking the far-flung regions of the earth. One by one, then, each of the established pillars of medieval civilization were decisively displaced during the long nineteenth century.4Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century, trans. Patrick Camiller (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 47.

An era of ideological frustration

The upheavals of the long nineteenth century aroused a gusty season of intellectual commotion and ferment. How, every attentive mind began to wonder, should a just, peaceful, and prosperous society be structured if not by the age-old medieval pillars of village-based agrarianism, monarchical empire, and ecclesiastical religion? Given the outsized influence that, at the time, European and North American peoples enjoyed, many intellectuals attempted to answer this question by presenting certain impressive features of modernizing Western societies—their pursuit of rational self-determination; their relentless strivings for scientific and technological progress; their expanding commitments to democratic politics and the self-correcting dynamism of free markets; their burgeoning schemes of political-economic equalization; or even their nationalistic enthusiasms—as the crucial foundations of a new, modern order of civilization that all peoples must eventually embrace.

The Western-centric inquiries of nineteenth-century thinkers yielded a constellation of influential ideologies—including liberalism; capitalism; socialism; nationalism; anarchism; secular humanism; scientific materialism; organicism; techno-utopianism; and enlightened despotism—that illuminated certain real features of the modern age of transition. Yet these ideologies also each employed so many problematically one-sided and parochially self-centered assumptions that subsequent efforts to enact their claims ended up lurching back and forth between moments of encouraging progress and of demoralizing frustration. One thinks, for example, of how the efforts of revolutionary France to politically enact the ideals of liberty, equality, and solidarity were swiftly followed by the authoritarian repressions of the Reign of Terror and the Napoleonic regime. Or one could also mention how endeavors to demonstrate the universal validity of modern science, advanced by such thinkers as Denis Diderot (1713-1784) and August Comte (1798-1857), helped to stimulate a encouraged new constellation of obscuring materialistic orthodoxies.

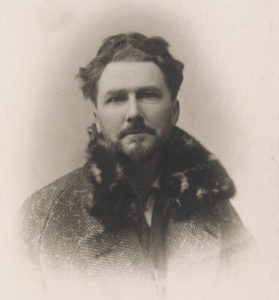

Noting these difficulties, long-nineteenth-century thinkers strove to remedy the many defects that plagued their cherished modern ideologies in at least three broad ways. First, there were those who, like J.W.F. Goethe (1749-1832), John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), Karl Marx (1818-1883), and Walt Whitman (1819-1892), claimed that humanity could only continue proceeding down the path of modern progress by more consistently or radically embracing the ideals of the Enlightenment, particularly those of freedom, equality, and rationality. Second, many others advanced the countervailing claim that redressing the ideological failings of Western modernity required revitalizing one or another of humanity’s great pre-modern traditions; consider, for example, of the efforts of Friderich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Søren Kierkegaard (1817-1855), and the architects of the Meiji Restoration, respectively, to re-engage the ethos of Homeric polytheism, of early Christianity, and of Japanese Shintoism. And third, one encounters an expanding cohort of voices who, in the manner of a Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) or Max Stirner (1806-1856), suggested that a more ideal society could emerge only after the West’s moral-ideological pretensions had been firmly subverted and exposed. The intellectual landscape of the long nineteenth century was, therefore, cross-pressured by efforts to show how the crucial defects of Western modernity could be resolved by more comprehensively embracing Enlightenment ideals, or by revitalizing some premodern ethico-spiritual tradition, or by critically vitiating the dark side of modern Western civilization.

Much has obviously taken place since the close of the long nineteenth century, including such world-shaking events as the Great Depression; the Second World War; the nuclear proliferations of the Cold War; decolonization and the third wave of nation-state formation; the “Big Push” of international development; the formation of the United Nations; the establishment of the international human rights regime; the rising global clout of East and South Asian societies; the digital revolution; and the accelerating trajectory of anthropocentric climate change. And yet, dominant intellectual discourses—especially in the West—continue to swirl within the same limited horizon of ideological possibilities that crystallized between 1770 and 1920. Indeed, despite the impressive advancements in knowledge that have taken place during the century, many among our most prominent thinkers continue to assume that, if contemporary humanity is ever to address its mounting civilizational woes, it must do so either by re-committing itself to the ideals of the Enlightenment, renewing its engagement with some older and ostensibly superior tradition, or disruptively deconstructing the oppressive and disingenuous foundations of modern Western civilization.

The analogy of collective adolescence

The age of transition thesis discloses a new horizon of interpretive possibilities. It recasts the tumultuous vectors of modern thought and social change as the initial expressions of a still-unfolding process of global-civilizational transformation that can be likened to the collective adolescence of humankind. “The long ages of infancy and childhood through which the human race had to pass, have receded into the background,” proclaims Shoghi Effendi, who served as the administrative head of the Bahá’í Faith from 1921 to 1957, in a letter written several years before the outbreak of the Second World War. “Humanity is now experiencing the commotions invariably associated with the most turbulent stage of its evolution, the stage of adolescence, when the impetuosity of youth and its vehemence reach their climax, and must gradually be superseded by the calmness, the wisdom, and the maturity that characterize the stage of manhood. Then will the human race reach that stature of ripeness which will enable it to acquire all the powers and capacities upon which its ultimate development must depend.” Or again, as the Universal House of Justice explains, “the human race, as a distinct, organic unit, has passed through evolutionary stages analogous to the stages of infancy and childhood in the lives of its individual members, and is now in the culminating period of its turbulent adolescence approaching its long-awaited coming of age.”5Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, www.bahai.org/r/166959448; Universal House of Justice, The Promise of World Peace, www.bahai.org/r/562133059.

This image warrants careful consideration. For individuals, the period of adolescence is marked by the rapid development of adult-like capabilities. Yet a mature framework within which to orient these new powers is initially lacking. The young person must struggle to clarify the concepts, values, and identities upon which they will rely as they approach the threshold of adulthood. This is an immensely challenging task, and it is made even more difficult by the young person’s competing attachments to the well-known norms of childhood, burgeoning enamorments with their own mental and physical capabilities, and deepening uncertainties about the merits of different models of adult living. Indeed, it is precisely from the resultant sense of disorientation that arise the patterns of “turbulence,” “impetuosity,” and “vehemence” that are so consistently associated with the period of human adolescence.

When applied to the modern age of transition, the analogy of adolescence recasts the proliferating welter of modern ideologies, not as the expression of some unsurpassable state of social, political, and intellectual maturity, but rather as the chaotic yet promising outgrowth of humanity’s burgeoning abilities to envision a new era of a globally-integrated civilization. The analogy additionally encourages a long-term vision of social change that can enable successive generations to continue laboring to erect an organically transfigured world society. In this regard, one might consider the difference between the young person who, because they see themselves living only for today, dissipates their energies in the pursuit of fleeting pleasures and enthusiasms, and another, who, by remaining more acutely aware of the looming imperatives of adulthood, conscientiously devotes themselves to undertakings that prepare them for what lies ahead.

The effort to analogically reconfigure one’s narrative of history, moreover, helps clarify the crucial role that other analogies already play in shaping thought about modern history. Indeed, the very notion of enlightenment constitutes one such influential analogy, suggesting the ideals of banished illusion and of rationally clarified perception that have profoundly influenced the trajectory of modern Western culture and history. And one can also readily identify several other images—based, for example, on the model of atomic interaction, or on the naturally selective pressures of jungle life, or even on the operations of industrial factories and mechanical clocks—that continue to orient prevalent ideas about specific features of modern social existence. Consequently, instead of aspiring to supplant the ostensibly objective and neutral narratives of modernity that contemporary intellectuals employ with an unduly imagistic one, the age of transition thesis actually endeavors to transform the existing analogical contents of modern historical imagination.

Toward a new horizon of research and intellectual activity

If the age of transition thesis is to ever become widely influential, much more will be required than simply enumerating its various conceptual and interpretive merits. The idea must additionally be incorporated into a new and robustly advancing pattern of research and intellectual activity. To shed further light on how an expanding constellation of individuals, communities, and institutions might practically address this far-reaching challenge and opportunity, the author draws on his experience with a nascent research organization, the Center on Modernity in Transition. Before exploring this particular body of experience, however, it may be useful to offer some additional insight into the intellectual transformation that is being considered by briefly exploring the history of the modern research university.

The institution of the modern research university arose in Germany during the early nineteenth century, and is widely recognized as beginning with the founding of the University of Berlin in 1809. Unlike its medieval predecessors, such as the universities of Paris or Oxford, which functioned as scholastic guilds that pursued the ideal of orthodox intellectual integration, the modern research university was meant to advance intellectual endeavors that grew out of the novel idea of modernity as a dawning age of rational and scientific enlightenment. One major strategy that these universities employed was to situate the proliferating research activities that Enlightenment thinkers pursued within a handful of specialized disciplines and fields. As explained by the well-known Enlightenment philosopher, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the modern research university was to lead humanity further into the dawning Age of Enlightenment by managing “the entire content of learning … like a factory, so to speak—by a division of labor, so that for every branch of the sciences there would be a public teacher or professor appointed as its trustee, and all of these together would form a kind of learned community called a university.”6Immanuel Kant, “The Conflict of the Faculties (1798),” in Religion and Rational Theology, trans. Mary J. Gregor and Robert Anchor, The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 247. The disciplinary order of knowledge that now orients our world thus arose within the efforts of modern research universities to systematically embed the idea of modernity as a dawning age of enlightenment in a new pattern of research and intellectual activity. By extension, it would seem reasonable to expect the mature development of the idea of modernity as an age of transition to entail at least an equally weighty and institutionally complex transformation in the intellectual life of humankind.

The writings of philosopher Imre Lakatos (1922-1974) further illuminate the actual process by which such an intellectual transformation might proceed. Specifically, Lakatos claims that every serious research endeavor relies upon a “hard core” of conceptual presuppositions that are never directly tested, but rather used to support an evolving “protective belt” of rigorously evaluated theories, propositions, and methodologies. For Lakatos, the main distinction between a scientific program of research and a non-scientific one lies not in the extent to which they respectively employ empirically unverified assumptions—both of them inescapably do—but rather in the degree to which their conceptual presuppositions sustain a progressively advancing system of secondary theories, propositions, and methodologies. Consequently, instead of endeavoring to conclusively demonstrate the veracity of the age of transition thesis before proceeding any further down the path of inquiry that the idea suggests, Lakatos’s arguments suggest that one must simply get started trying to use the idea to ground a new and robustly advancing program of research and intellectual activity.7Imre Lakatos, The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Volume 1: Philosophical Papers (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1980).

In this regard, it may be useful to mention the nascent efforts of one research organization. the Center on Modernity in Transition (COMIT), with which the author has, since its establishment in early 2020, been energetically engaged. As the organization explains in a recent report, “the Center on Modernity in Transition aspires to contribute to the intellectual life of the emerging world civilization envisioned by Bahá’u’lláh. We begin from the premise that if one interrogates deeply enough the sources of humanity’s pressing challenges, one arrives ultimately at a network of concepts and assumptions that undergird the current order, and that shape the ways in which social reality is read, understood, and constructed. The broad aim of COMIT is thus to rigorously examine the intellectual foundations of modern society and to contribute, however gradually, to their transformation. COMIT pursues this goal by working to establish a new and dynamic research program animated by the idea of modernity as an age of transition toward a new world civilization—one characterized by unprecedented levels of unity, justice, peace, and material and spiritual prosperity.”

In support of its long-term, research-program-building agenda, the Center pursues two interrelated areas of activity. COMIT aspires to advance novel and distinctive lines of research that are rooted in the idea of modernity as an age of transition, as well as in the various fundamental concepts that underpin the idea. At the same time, however, the organization strives to contribute to a growing number of academic discourses and fields that, in one way or another, help to illuminate various facets of the modern age of transition. Neither endeavor can, the Center maintains, be effectively pursued in isolation from the other. For without consistently engaging the best knowledge and methodologies that humanity has produced, COMIT’s attempts to build a new research program would struggle to significantly improve upon the patterns of intellectual activity that operate within the world’s leading research universities. Inversely, however, if the Centre focuses only on advancing the kinds of research that existing academic institutions pursue, it would soon find itself unable to meaningfully contribute to the establishment of a new and highly distinctive program of research and intellectual activity. COMIT thus aspires to advance both endeavors in a complementary and coherent manner.

A series of initial developments suggests the fecundity of COMIT’s approach. Relevant examples include the establishment of fruitful collaborations with academic bodies at Duke University, New York University, and Columbia University; the successful execution of a number of online speaker series—for example, The Liberal Imaginary and Beyond and Identity and Belonging in a Global Age—featuring a line-up of highly distinguished thinkers and practitioners, including Charles Taylor, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Barbara Fields, Cornel West, Seyla Benhabib, and Craig Calhoun; the development of a maturing web presence, particularly the organization’s webpage, comitresearch.org, and its YouTube channel, where video recordings of its events have been widely viewed; the raising of an initial tranche of funds to support the organization’s expanding research activities and the hiring of personnel; the establishment of several dynamic, distinctive, and externally well-received research projects; and the cultivation of an expanding network of committed thought partners and research collaborators. Although the organization remains acutely aware of the many challenges it must face as its efforts continue to gain in complexity and scope, it continues to derive sustenance and hope from the demonstrated abilities of the age of transition thesis to invite the enthusiastic participation of scholars situated within a wide variety of disciplinary, intellectual, and ethico-spiritual traditions.

What this article suggests is that, today, there is a unique opportunity for motivated researchers to begin rigorously embedding the distinctive vision of modernity as an age of transition, such as it is presented in the Bahá’í writings, into new and far-reaching patterns of research and intellectual activity. The example of the Center on Modernity in Transition provides some insight into the kinds of evolving research activities that might help to tangibly advance the envisioned intellectual transformation. At present, however, the simple fact remains that we can have little real knowledge of the precise content or shape of this future intellectual efflorescence. It is precisely for this reason that the Bahá’í writings consistently encourage us to regard the welter of tumultuous forces that characterize the modern age of transition through the lens of the organic metaphor. “It is,” as ‘Abdu’l-Baha writes, “even as the seed: The tree exists within it but is hidden and concealed; when the seed grows and develops, the tree appears in its fullness.”8’Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions: www.bahai.org/r/771160088. The immediately pressing task before us is for an expanding constellation of individuals, communities, and institutions to begin boldly and systematically pursuing the myriad opportunities for serious intellectual transformation and growth that can be discerned within the immediate contexts of their lives and social milieus.

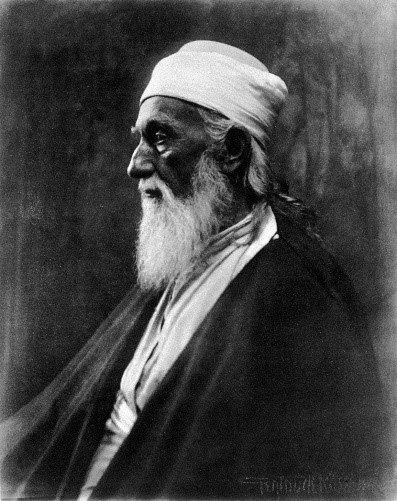

On 10 September 1911 and at the age of 67 years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá delivered the first public address of His life. From the pulpit of the City Temple in London, He announced to the reported 3,000-strong congregation: “This is a new cycle of human power.” Humanity’s dynamic acceleration toward greater levels of unity, He explained, was a consequence of the “light of Truth … shining upon the world.”1‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.19.

Throughout the ensuing two years of His travels, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá—finally free after more than half a century of imprisonment and exile—continued to elucidate, in both open presentations and private conversations, the distinctive capacities of humanity in this “new day.”2‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.19. In Paris, for example, He stated:

Look what man has accomplished in the field of science, consider his many discoveries and countless inventions and his profound understanding of natural law.

In the world of art it is just the same, and this wonderful development of man’s faculties becomes more and more rapid as time goes on. If the discoveries, inventions and material accomplishments of the last fifteen hundred years could be put together, you would see that there has been greater advancement during the last hundred years than in the previous fourteen centuries.3‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Paris Talks. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing, 2006, p.84.

By the early years of the twentieth century, such advances were familiar in the Western societies into which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá ventured, which had been impacted by the scientific challenge to Bible-centric worldviews, technological progress and urbanization, shifts in governance and global consciousness, the intensification of financial exchange and improvements to the status of women. These and numerous other advancements—also taken up in distant corners of the planet, many of which had been annexed, colonized and influenced by Imperialist powers—are often included in the humanities and social sciences as some of the characteristics of “modernity.”

Concurrently, a wide variety of beliefs and practices later labelled ‘modernist’ were taking root. Ideals of truth, reason, and liberty were shared through diverse branches of human thought and endeavor, ranging from the materialistic to the esoteric. For the purposes of this exploration pertaining particularly to cultural pursuits, ‘modernism’ might be seen as both an outcome and, at times, a rejection of aspects of modernity. Rebelling against widely accepted norms, modernists in the arts set out to shun tradition and break rules, or at least push them to their limits. Painters dismissed the accurate depiction of reality, exploring instead the expressive and space-defining potential of color, experimented with abstracted forms, and revealed their process in the creation of an image; composers tested novel approaches to melody, harmony and rhythm; dancers drew upon the gestures of daily life or looked back to ancient civilizations for physical movements that stretched the possibilities of bodily expression; writers and dramatists departed from the established rules of prose, poetry, and playwriting to articulate the new sensibilities of the time. Some modernists conceived of utopian visions of society, albeit in certain cases by spreading the supremacy of their own nationalistic cultural heritage over neighboring traditions. At the heart of all of this burgeoning experimentation, however, was an aspiration for change, to which the subjective ‘self’ of the practitioner was central.

Ironically, while modernists often scorned uniformity and the imposition of Western values on the earth’s populations, they also turned for inspiration to the very cultures that were then becoming even more familiar to the public as a result of the expansionist ambitions of the powers under which they lived. A new universal art, some modernists believed, would emerge as they opened their eyes to what they considered to be the exciting, radical, and inventive qualities of the folk art and tribal crafts of the colonies, on display in museums and great expositions. Often it was the enormous wealth—extracted from colonialized subjects abroad and exploited lower classes at home—that enabled modernist projects, pursuits, and indulgences in the West.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, when Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution began to mount its challenge to the Biblical, anthropocentric conception of creation, the search for “an exotic and syncretic world religion” also became “an early modernist aim.”4Bernard Smith. Modernism and Post-Modernism, a neo-Colonial Viewpoint. Working Papers in Australian Studies, Sir Robert Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, 1992 New translations made accessible such religious texts as The Upanishads, The Bhagavad-Gita, and the Tao Te Ching. Elements of the religions of India and Tibet—and the more mystical strands of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—were incorporated into modernist thinking, often through the teachings of the Theosophical Society, and especially among women seeking a spirituality that cut out the literal middle man.

Such was the burgeoning cultural landscape in the West when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived with His message of the dawning of a new era in human evolution, in which the unity and equality of all humanity would be recognized and conflict and contention would give way to an enduring peace.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s discourse on progress was rooted in the conviction that the discoveries and developments of the age represented an instinctive response on the part of humanity to a new infusion of divine power into creation. Fundamental to the Bahá’í conception of history is the belief that, when a Manifestation of God appears in the world, the accompanying forces required to accomplish His divinely-ordained purpose are also released, setting in motion irresistible processes of societal transformation. Bahá’u’lláh proclaimed:

The world’s equilibrium hath been upset through the vibrating influence of this most great, this new World Order. Mankind’s ordered life hath been revolutionized through the agency of this unique, this wondrous System—the like of which mortal eyes have never witnessed.5Bahá’u’lláh. Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1978, LXX, p.135.

The spiritual forces released by the Revelations of the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh were thus breaking down barriers and pushing an unknowing humanity toward the consciousness and realisation of its essential oneness, regardless of race, gender, class, or other divisive factors. Such forces had deranged the stability of the existing world order and instigated transformation at every level:

Through that Word the realities of all created things were shaken, were divided, separated, scattered, combined and reunited, disclosing, in both the contingent world and the heavenly kingdom, entities of a new creation …6Bahá’u’lláh. Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1978, LXX, p.135.

These “spiritual, revolutionary forces,” observed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s grandson Shoghi Effendi, Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith, “… are upsetting the equilibrium, and throwing into such confusion, the ancient institutions of mankind.”7Shoghi Effendi. The Promised Day is Come. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1980, p.95 Humanity, either in its overt resistance to—or in its attempts to stimulate—social transformation was, in Shoghi Effendi’s analysis, experiencing the “commotions invariably associated with the most turbulent stage of its evolution, the stage of adolescence, when the impetuosity of youth and its vehemence reach their climax …”8Shoghi Effendi. ‘The Unfoldment of World Civilization’, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1991, p.202 While the internal physiological processes within an individual trigger the onset of adolescence, the release into the world of Divine Revelation affects the inner fibre of human life and thought, and has an impact far beyond the personal orbit of a Manifestation of God and those who physically hear His message or respond directly to His call. It suffuses every aspect of existence and at a subliminal level is received by sensitive human hearts and minds, as yet oblivious to its source.

At the time of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s arrival in Paris on 3 October 1911, the French capital was maintaining its status as the most fertile arena for artists, writers, and musicians—including countless Americans—engaged in a passionate quest to live and work free from stifling convention. “I like Paris because I find something here, something of integrity, which I seem to have strangely lost in my own country,” wrote the African-American writer Jessie Redmon Fauset. “It is simplest of all to say that I like to live among people and surroundings where I am not always conscious of ‘thou shall not.’”9Shari Benstock. Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900-1940. London: Virago, 1986, p.13 For women such as Fauset, who were escaping their homeland, where even educated Black citizens were still prohibited from participating in most social spaces, Paris offered the opportunity for fearless experimentation and acceptance. It was a city in which scientists such as the Polish Nobel Prize-winning physicist and chemist Marie Curie could train and embark on their careers, and where literary salons—including those hosted by expatriates Gertrude Stein and Natalie Clifford Barney—flourished, offering spaces where artists and writers could uninhibitedly share their ideas and work.

Women had also played a significant role in the establishment, in Paris, of the first Bahá’í centre in Europe at the close of the nineteenth century. Through the efforts of May Ellis Bolles (later Maxwell), many important figures in early Western Bahá’í history embraced the message of Bahá’u’lláh in the city. Among them were other Americans and Canadians, including painters such as Juliet Thompson and Marion Jack, and heiress Laura Clifford-Barney, Natalie’s sister. Impressionist painter Frank Edwin Scott, architect William Sutherland Maxwell, poet and art gallery manager Horace Holley and the Irish-born philanthropist Lady Blomfield also first came across the Bahá’í teachings in Paris. Experimental dancer Raymond Duncan, brother of the more renowned Isadora, and composer Dane Rudhyar were included in the Bahá’í circle. Rudhyar was a modernist who intuitively felt that Western civilization was coming to “the autumn phase of its cycle of existence.”10Rudhyar Archival Project. http://www.khaldea.com/rudhyar/bio1.shtml Later composing Commune—based on the words of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá— Rudhyar deemed the Bahá’í message to have embodied “clearly the most basic keynotes of the collective spirit of the age …”11Dane Rhudyar, cited in The Bahá’í World Vol. XIII 1954-1963. Haifa: The Universal House of Justice, 1970, p.829

To exhausted communities of the world [the Bahá’í Revelation] gives vital impetus which, we hope, will soon energize new creative manifestations and produce an inspired art, equal or superior to that of early Christianity.12Dane Rhudyar, cited in The Bahá’í World Vol. XIII 1954-1963. Haifa: The Universal House of Justice, 1970, p.829.

Many artists and writers of the period were continuing to take a Symbolist approach. As a prelude to more far-reaching forms of abstraction, Symbolists strove to represent universal truths through metaphorical language and imagery, in an attempt to “illumine the deepest contradictions of contemporary culture seen through the prism of various cultures.”13Andrei Bely. The Emblematics of Meaning: Premises to a Theory of Symbolism, 1909 The novelist Andrei Bely wrote:

… we are now experiencing, as it were, the whole of the past: India, Persia, Egypt, Greece … pass before us … just as a man on the point of death may see the whole of his life in an instant … An important hour has struck for humanity. We are indeed attempting something new but the old has to be taken into account …14Andrei Bely. The Emblematics of Meaning: Premises to a Theory of Symbolism, 1909

It seems natural, then, that the opportunity to see in person a striking, venerable figure from Persia was intriguing to those who sought enlightenment from the East to find a language appropriate for expressing the modern world. The influential critic and Symbolist poet Remy de Gourmont, for example, met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Paris on 20 October 1911. From Gourmont’s account, published in La France, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá appears to have been alert to the fact that he was a writer for whom a metaphorical depiction of spiritual reality would have appeal:

… The eloquent patriarch spoke to us of the simple joys experienced in the Bahá’í city, of pleasures designed to delight the docile hearts, where spring is eternal, ever-flowering with the perpetual blooming of lilies, violets and roses, where women smile and men are happy in the perfume air of love. And we spoke of the great truth that excels all the previous truths, in which our little human errors are melted and transformed, as such quarrels disappear in the shade of the greatest Peace. And we felt a deep passion in the faintly halting voice, roughly punctuated by the guttural sounds of the Persian language, but also gently punctuated by the phrasing of his musical laughter. For the prophet is joyful and we all feel within him the gaiety of being a prophet, upon whom forty years of prison have left no trace. He had with him a bouquet of violets, offering one to each of his visitors; to the most resistant to his teachings and to those who had the audacity to stubbornly oppose him, the parma violets serve as his arguments, as do his hearty laugh, his beautiful and poetic arguments, and the simplicity of his Persian dress.15 See Amin Egea. The Apostle of Peace Vol.1: 1871-1912. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 2017, p.164.

Evidently touched by their exchange, Gourmont urged his readers to seek out ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s public appearances. Subsequently, using a pseudonym, Gourmont even penned a review of his own La France article for another journal.

Another significant modernist who learned of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was Guillaume Apollinaire, although whether they met is not known. One of the foremost poets of the early twentieth century and a close associate of such emerging painters as Picasso, Braque, and Marie Laurencin, Apollinaire is credited with coining the terms “Cubism” in 1911 and “Surrealism” in 1917. His “Le Béhaisme” appeared in the Mercure de France on 17 October 1917. That article concludes:

A new voice is coming out of Asia. Already many in Europe believe that the word of Beha-Oullah[sic] does not contradict our modern science and can be assimilated for we[sic] Europeans, who need comforting. Isn’t it just that this comfort comes to us from Asia as it came before?16Guillaume Apollinaire, “Le Béhaisme.” Mercure de France, 16 October 1917, p.768

In like manner, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s stay in London was widely reported in the publications of the day. One weekly magazine, aptly titled The New Age and supported by the future Nobel Prize-winning writer George Bernard Shaw, was dedicated to publishing modernism in literature and the arts. In its 21 September 1911 edition, two weeks after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s arrival in the city, The New Age reported, “Seeds of strange religions are wafted from time to time on our shores. But fortunately or unfortunately, they do not find the soil in us in which to flourish … The latest to land in public is Bahaism, of which, indeed many of us have heard in private these many years.”17A.R. Orage. “Notes of the Week.” New Age 9, September 1911, p.484

The pioneering modernist poet Ezra Pound was a regular contributor to The New Age. The day after “Bahaism” was mentioned in its pages, Pound stated somewhat arrogantly to his future wife, Dorothy Shakespear, “They tell me I’m likely to meet the Bahi[sic] next week in order to find out whether I know more about heaven than he does …’18Ezra Pound, cited in Elham Afnan, “‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Ezra Pound’s Circle”, The Journal of Bahá’í Studies Volume 6 No.2, June-September 1994, p.8 Following their meeting, Pound then wrote to Margaret Cravens, a friend who lived in the French capital, “I met the Bahi yesterday, he is a dear old man. I wonder would you like to meet him, he goes to Paris next week. I’ll arrange for you anyhow and you can go or not, as you like.”19Omar Pound and Robert Spoo, editors. Ezra Pound and Margaret Cravens: A Tragic Friendship 1910-1912. Durham: Duke University Press, 1988, p.90. In a further communication to Cravens, Pound was clearly eager for his friend to see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, placing His significance above that of the French post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne:

The Bahi—Abdul Baha, Abbas Effendi, or whatever you like to call him is at the Dreyfus Barney’s … and any one interested in the movement can write and see him there by appointment. It’s more important than Cezanne, & not in the least like what you’d expect of an oriental religious now. At least, I went to conduct an inquisition & came away feeling that questions would have been an impertinence. The whole point is that they have done instead of talking …20Omar Pound and Robert Spoo, editors. Ezra Pound and Margaret Cravens: A Tragic Friendship 1910-1912. Durham: Duke University Press, 1988, p.95.

Despite Pound’s later, well-documented inclination towards fascism—which is about as ideologically far removed as can be imagined from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s purpose—it nevertheless appears that he was momentarily disarmed by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The poet even revived his memory of that day more than two decades later in his monumental verse cycle The Cantos. “Pound did not interest himself in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s message beyond expressing approval of its unexpected modernity,” literature scholar Elham Afnan has observed, yet the “portrait of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá [in Canto XLVI], despite its flippancy, is basically sympathetic and as respectful as Pound can manage to be.”21Elham Afnan, “Abdu’l-Bahá and Ezra Pound’s Circle”, p.11.

Pound was also a contributor to the modernist journal Blast, in which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s name appeared in a somewhat surprising fashion. Blast was the creation of the painter and novelist Percy Wyndham Lewis, founder of the short-lived Vorticist movement, which was inspired by the Cubism of Picasso and Braque, and the Italian Futurists’ celebration of the machine age. The first edition of Blast contained an extensive list of people, institutions, and objects that were, in the Vorticist view, either “Blessed” or “Blasted.” Curiously, included among those “Blasted” is the name “Abdul Bahai.” Since there is no record of Wyndham Lewis having met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the inclusion of His name in such a provocative list is perhaps more indicative of the contempt in which Blast’s editors held organized religion, or anything they deemed “bourgeois” and “establishment,” which may have encompassed the involvement of wealthy Londoners in Eastern movements.

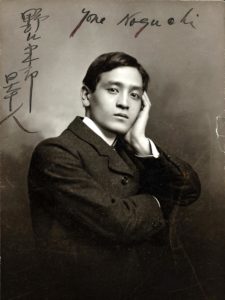

In time, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s fame reached and impacted modernists much farther afield than the cities in which He spoke. In August 1911, the influential Japanese writer Yone Noguchi had sent Ezra Pound two books of his poems. Pound was very taken with Noguchi’s work, saying, “If east and west are ever to understand each other that understanding must come slowly and come first through art.”22Cited in Howard J.Booth and Nigel Rigby, Modernism and Empire. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000, p.82.

Noguchi later learned of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá from Agnes Alexander, a Hawaiian-born Bahá’í who had been sent by Him to share the Bahá’í Teachings in Japan.23Agnes Baldwin Alexander, History of the Bahá’í Faith in Japan 1914-1938. Tokyo: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1977, p.41. Noguchi wrote:

I have heard so much about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, whom people call an idealist, but I should like to call Him a realist, because no idealism, when it is strong and true, exists without the endorsement of realism. There is nothing more real than His words on truth. His words are as simple as the sunlight; again like the sunlight, they are universal. … No Teacher, I think, is more important today than ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.24Yone Noguchi, cited in The Bahá’í World Vol. VIII 1938-1940. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981, p.624.

During the early days of the First World War, Agnes Alexander also introduced the Bahá’í Faith to the highly influential English potter Bernard Leach, who recalled: “We asked what had brought her to Japan and I was struck by the quietness of her smile when she answered ‘… you will not understand, but I came because a little old Persian Gentleman asked me to come.’”25Bernard Leach, “My Religious Faith” in Robert Weinberg, ed., Spinning the Clay into Stars. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 1999, p.60. Leach—who became the most significant figure in the revival of craft pottery in modern Britain—dedicated his entire life to encouraging the union of East and West, fully embracing the Bahá’í Faith in 1940 after he was re-introduced to it by the American painter Mark Tobey, when they were both teaching at the progressive arts school Dartington Hall in Devon, England.

Also favorable in his response to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was another enthusiast for modernism, Professor Michael Sadler. A progressive educationalist and university administrator, Sadler was president of the Leeds Arts Club, which mixed socialist and anarchist politics with the philosophy of Nietzsche, suffragette feminism, Theosophy, avant-garde art, and poetry. Sadler built up a remarkable collection of art, including a Symbolist masterpiece by Paul Gauguin and works by the Russian Expressionist painter Wassily Kandinsky, at a time when his paintings were either unknown or dismissed in London, even by well-known supporters of modernism. In Kandinsky’s seminal 1911 treatise, Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), translated into English by Sadler’s son, the painter proposed that abstraction in painting was the best weapon for transforming a corrupt, materialist society.

Michael Sadler presided over ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s farewell talk at the conclusion of His first visit to London, on 29 September 1911, saying:

We have met together to bid farewell to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, and to thank God for his example and teaching, and for the power of his prayers to bring Light into confused thought, Hope into the place of dread, Faith where doubt was, and into troubled hearts, the Love which overmasters self-seeking and fear.

Though we all, among ourselves, in our devotional allegiance have our own individual loyalties, to all of us ‘Abdu’l-Bahá brings, and has brought, a message of Unity, of sympathy and of Peace. He bids us all be real and true in what we profess to believe; and to treasure above everything the Spirit behind the form. With him we bow before the Hidden Name, before that which is of every life the Inner Life! He bids us worship in fearless loyalty to our own faith, but with ever stronger yearning after Union, Brotherhood, and Love; so turning ourselves in Spirit, and with our whole heart, that we may enter more into the mind of God, which is above class, above race, and beyond time.26‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.34.

In January 1913, when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá travelled to Edinburgh, Scotland’s main proponents of modernist painting—known as the Scottish Colourists—were working abroad in France, where their pictures were exhibited and sold predominately by the Paris gallery managed by Horace Holley. Symbolism, however, was a strong component of the Celtic Revival movement, in which artists and writers drew inspiration from the ancient myths and traditions of Gaelic literature and the early British mediaeval style to create art in a modern idiom. While in Edinburgh, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke with a number of artists through introductions from leading Celtic Revivalist Sir Patrick Geddes, the celebrated philanthropist and town planner (who also had the dubious honor of being “blasted” by Wyndham Lewis). Geddes presided over a public gathering with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, saying of Him:

We approve of the ideal He lays before us of education and the necessity of each one learning a trade, and His beautiful simile of the two wings on which society is to rise into a purer and clearer atmosphere, put into beautiful words what was in the minds of many of us. What impressed us most is that courage which enabled Him, during long years of imprisonment, and even in the face of death, to hold fast to His convictions.27H.M. Balyuzi. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 1971, p.365.

Geddes invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to visit a protégé of his, the painter John Duncan and Duncan’s wife Christine who had connections to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s friends Wellesley Tudor Pole and Alice Buckton, who shared in her Spiritualist interests. Among Duncan’s paintings, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá viewed St. Bride—now housed in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art—depicting the Irish saint who, legend has it, was transported by angels from Ireland to Bethlehem to attend the birth of Christ. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reportedly blessed the paintings, much to the delight of the Duncans.

At the Edinburgh College of Arts, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also encouraged a prize-winning sculptor, Fanindra Nath Bose, from Calcutta. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá praised Bose’s work, suggesting he return to India to found a new school of sculpture.28H.M. Balyuzi. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, 1971, p.11. Later in 1913, Bose relocated to Paris to work under the great sculptor Auguste Rodin, which led to his becoming part of the “new sculpture” movement in Britain, creating small, figurative, Symbolist statues.

In addition to conversing with artists, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá occasionally agreed to have His portrait painted. During the nine days in April 1913 that He stayed in Budapest, Hungary, He sat three times for Róbert Nádler, a celebrated painter and teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts and president of the city’s Theosophical Society. Two decades later, Nádler warmly recalled the experience, saying, “I saw with admiration that in his facial expression peace, clean love, and perfect good intentions reflected themselves. He saw everything in such a beatific light; he found everything beautiful the outer life of the city, as well as the souls of its inhabitants.”29Cited in Martha Root, “‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Visit to Budapest”, in Kay Zinky, ed., Martha Root: Herald of the Kingdom. New Delhi: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1983, pp.361-370 Nádler’s sympathetic painting of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is unique among the portraits made of Him, taking an Impressionistic impasto approach, particularly in the treatment of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s gossamer-like beard, made up of rhythmic brushstrokes.

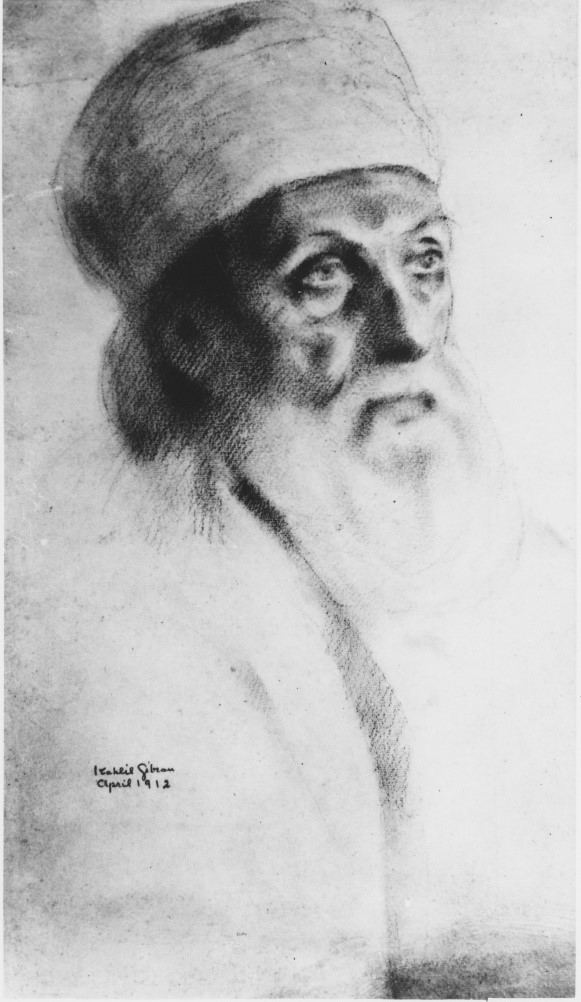

During ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s nine-month sojourn in North America, the most well-known literary personality to encounter Him was the Syrian-born, Lebanese-American writer and artist Kahlil Gibran, a central figure of Arabic literary modernism. Gibran arrived in New York City at the end of April 1911, his creative horizons having expanded during his exposure to modernists in Paris. Greenwich Village, where Gibran settled, was a gathering place for radical political and bohemian thinkers who were committed to an imminent revolution in human consciousness and social change. Art, they believed, would provide people with new values, giving rise to a new social order. In 1913, modern European art arrived forcefully in New York, when astonished Americans saw for the first time more than 300 avant-garde works at the infamous Armory Show. While remaining unmoved by most of the pieces on display, Gibran was sensitive to the motivations of modern artists, saying, “… the spirit of the movement will never pass away, for it is real—as real as the human hunger for freedom.”30Jean Gibran and Kahlil Gibran. Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World. Edinburgh, Canongate Press, 1992, p.252

Gibran “simply adored” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, recalled Juliet Thompson, who was Gibran’s neighbour. “He was with Him whenever he could be.”31Marzieh Gail, “Juliet Remembers Gibran”, Other People, Other Places. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, p.230. On 19 April 1912, Gibran sketched a portrait for which ‘Abdu’l-Baha sat and, for the rest of his life, “often talked of Him, most sympathetically and most lovingly.”32Marzieh Gail, “Juliet Remembers Gibran”, Other People, Other Places. Oxford: George Ronald Publisher, p.230. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá may well have been a source of inspiration for Gibran’s most famous work, The Prophet. The name of the book’s main protagonist Almustafa, it has been posited, resembles that of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá with only the consonants changed,33See David Langness, ‘The Bahá’í influence on Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet’. https://bahaiteachings.org/bahai-influence-on-kahlil-gibrans-the-prophet/ and the villagers in the narrative refer to him as ‘The Master,’ an appellation commonly used in relation to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. While Thompson did not later recall there being any definite connection between The Prophet and Gibran’s meeting with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the author did tell her that when he was writing The Son of Man, “he thought of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá all through.”34Gail, Other People, Other Places, p.228 He also expressed his intention—though it was never realised—to write a book specifically about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Juliet Thompson also arranged for ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to sit for the outstanding photographer Gertrude Käsebier. Since 1899, Alfred Stieglitz—a prominent New York gallery owner who championed American modernism—had promoted photography through his ‘Photo-Secession’ movement, which aimed to advance photography as a serious new art form and exhibit the finest work by American practitioners. Käsebier, who Stieglitz deemed to be the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day, was at the heart of Photo-Secession and believed the medium could be a particularly suitable art form and source of income for women. “I earnestly advise women of artistic tastes to train for the unworked field of modern photography,” she said in a lecture. “It seems to be especially adapted to them, and the few who have entered it are meeting a gratifying and profitable success.”35Cited in Stephen Petersen and Janis A. Tomlinson, eds. Gertrude Kasebier – The Complexity of Light and Shade. University of Delaware Press, 2013, p.11.

Käsebier had distinguished herself by her sympathetic, powerful portraits of America’s indigenous peoples, focusing on their expressions and individuality, rather than costumes and customs, a sensitivity she deployed in her portrait session with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on 20 June 1912. “I shall never forget the Master’s beauty in the strange cold light of her studio,” wrote Thompson in her diary, “a green, underwater sort of light, in which He looked shining and chiselled, like the statue of a god. But the pictures are dark shadows of Him.”36Juliet Thompson. The Diary of Juliet Thompson. Los Angeles: Kalimát Press, 1983, p.317. Kasebier, though, told Thompson afterwards, that she would like to live near Him.

Although those who came into contact with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá were deeply impacted by His presence and personality, some appear not to have consciously or explicitly made the profound connection between the Revelation He propagated and the revolutionary period during which they were making their distinctive mark. Yet, other leading modernists did respond more directly and thoughtfully to His Message.

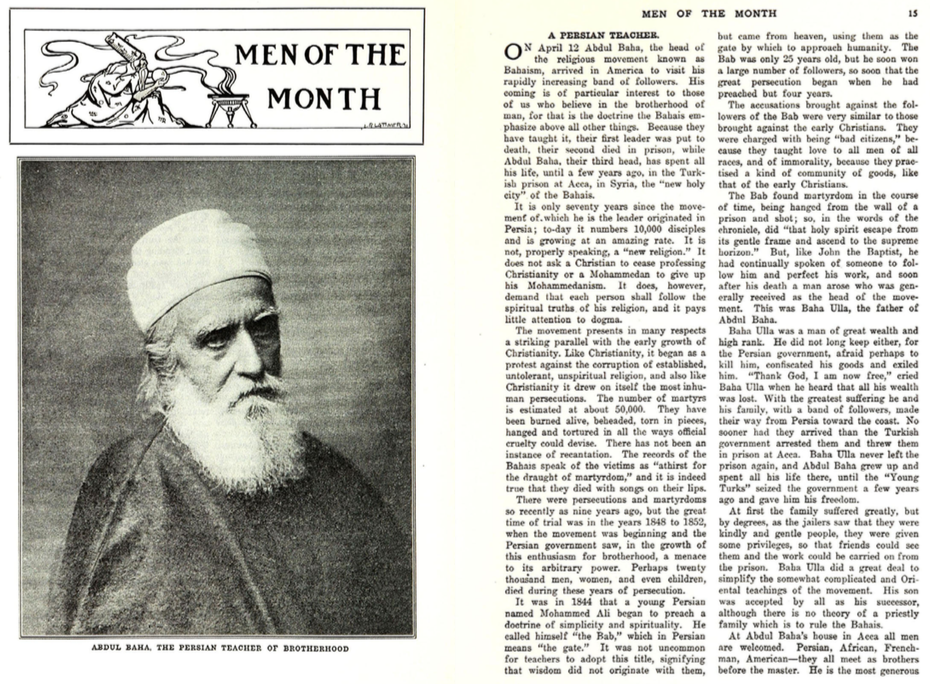

One of the Bahá’í principles promulgated with urgency by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during His travels in the United States was the elimination of racial prejudice. His address at the fourth conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) made a strong impact, for example, on sociologist and writer W.E.B. Du Bois, who published ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s speech in full in the June 1912 edition of the NAACP’s official magazine The Crisis and made Him one of the ‘Men of the Month’ in the July issue. The Bahá’í teachings on race unity also resonated forcefully with Alain LeRoy Locke—the philosophical architect of the Harlem Renaissance artistic movement, which aimed to create a body of African American writing and art comparable to the best from Europe, to celebrate and transcend the stereotypes of black American culture and encourage social integration. Locke asserted that, drawing on African American sources, black “artists could transcend the narrow conventions of Western art creating a genuinely human art.”37Willliam B. Scott and Peter M. Rutkoff. New York Modern – The Arts and the City. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1999, p.139.

Locke formally accepted the Bahá’í Faith in 1918. Five years later, making his first pilgrimage to the Bahá’í Shrines in the Holy Land, he had a profoundly affecting experience in the Shrine of the Báb and the Shrine of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, where he became “strangely convinced that the death of the greatest teachers is the release of their spirit in the world. …”38Alain Locke. “Impressions of Haifa”, The Bahá’í World Vol.3, 1928-1930. Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1980, p.280.

Through their encounters with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, then, thousands of souls in the West came into direct contact with the human embodiment of the spiritual forces released by the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, a Revelation through which, although few of them discerned it, “… the whole creation was revolutionized, and all that are in the heavens and all that are on earth were stirred to the depths.”39Bahá’u’lláh. Prayers and Meditations. Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, CLXXVIII, p.295 One particular aspect of that Revelation, of which most of the artists and writers He met probably remained unaware, concerned the radical redefinition of art as being an act of worship. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described it thus to Juliet Thompson:

I rejoice to hear that thou takest pains with thine art, for in this wonderful new age, art is worship. The more thou strivest to perfect it, the closer wilt thou come to God. What bestowal could be greater than this, that one’s art should be even as the act of worshipping the Lord? That is to say, when thy fingers grasp the paintbrush, it is as if thou wert at prayer in the Temple.40Extract from a Tablet of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, www.bahai.org/r/925134802

This consecration of humanity’s creative pursuits would, as ‘Abdu’l-Bahá foresaw it, in the centuries ahead give rise to “a new art, a new architecture, fused of all the beauty of the past, but new.”41Cited in Star of the West, Vol.VI No.4, 15 May 1915, pp.30-1. Despite all of its cultural ferment and experimentation, then, the early years of the twentieth century—with its “landscape of false confidence and deep despair, of scientific enlightenment and spiritual gloom,”42Century of Light. Haifa, Bahá’í World Centre, 2001, p.7. a landscape on which the “luminous figure of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá”43Century of Light. Haifa, Bahá’í World Centre, 2001, p.7 appeared— might thus be seen merely as the first streaks of the dawn of a “new cycle of human power.”44‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987, p.19.

The author is grateful to Debra Bricker Balkan, Hari Docherty, Dannah Edwards, Sky Glabush, Jan Jasion, Michael Karlberg, Arlette Manasseh, Anne Perry, and Nathan Rainsford for their assistance in the preparation of this essay.