‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Reading of Social Reality

‘Abdu’l-Bahá is a figure unique in religious history. Understanding His critical role is essential to understanding the workings of the Bahá’í Faith – in its past, present, and future.

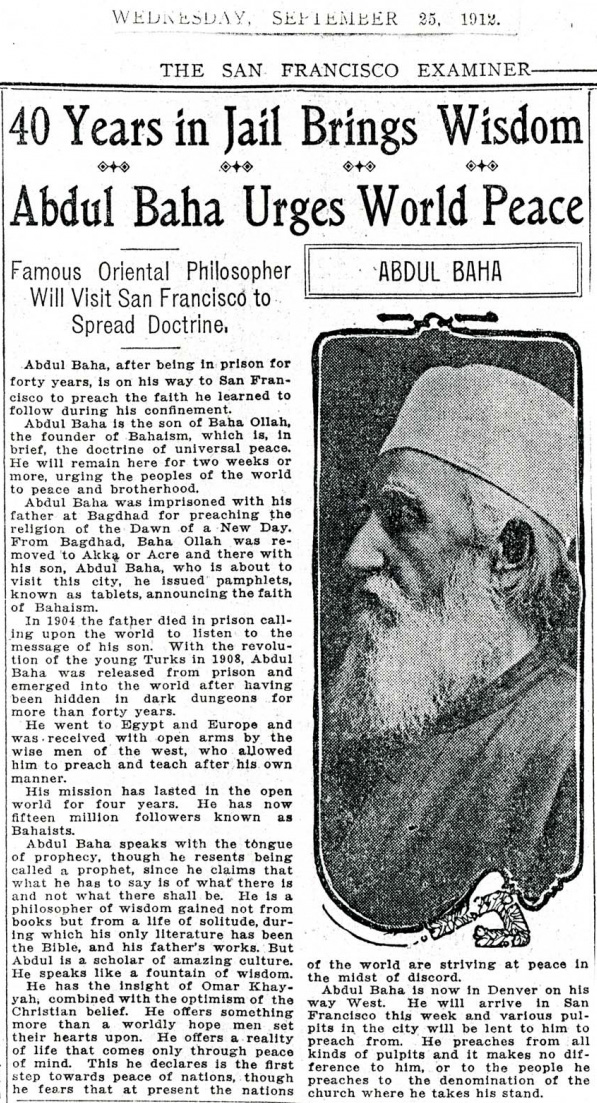

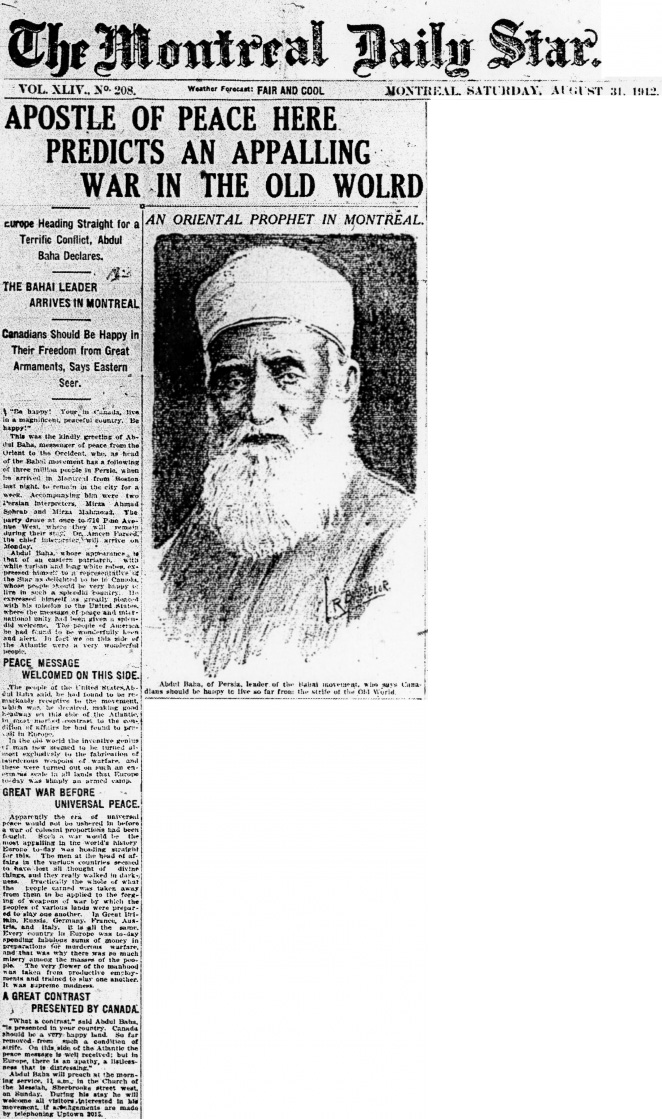

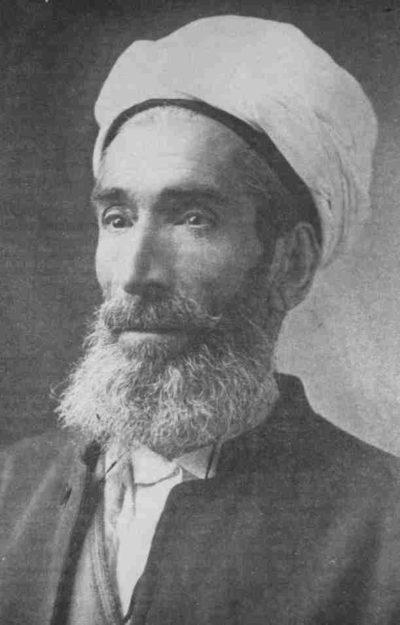

For forty years ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was a prisoner of the Ottoman Empire, having been exiled as a nine-year-old child, when members of Bahá’u’lláh’s family were expelled from Iran to the Ottoman domains. Undeterred by the restrictions to His freedom and the challenges of daily life, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá directed His attention to administering the affairs of the growing Bahá’í community and to easing the plight of humanity by actively promoting a vision of a just, united, and peaceful world.

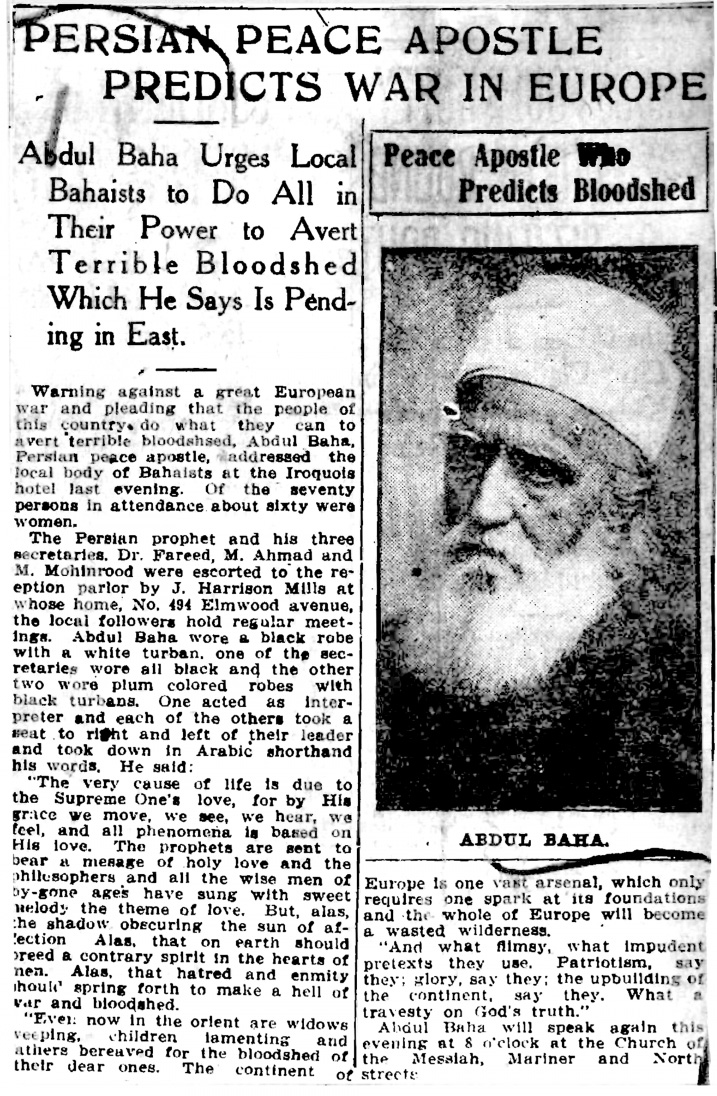

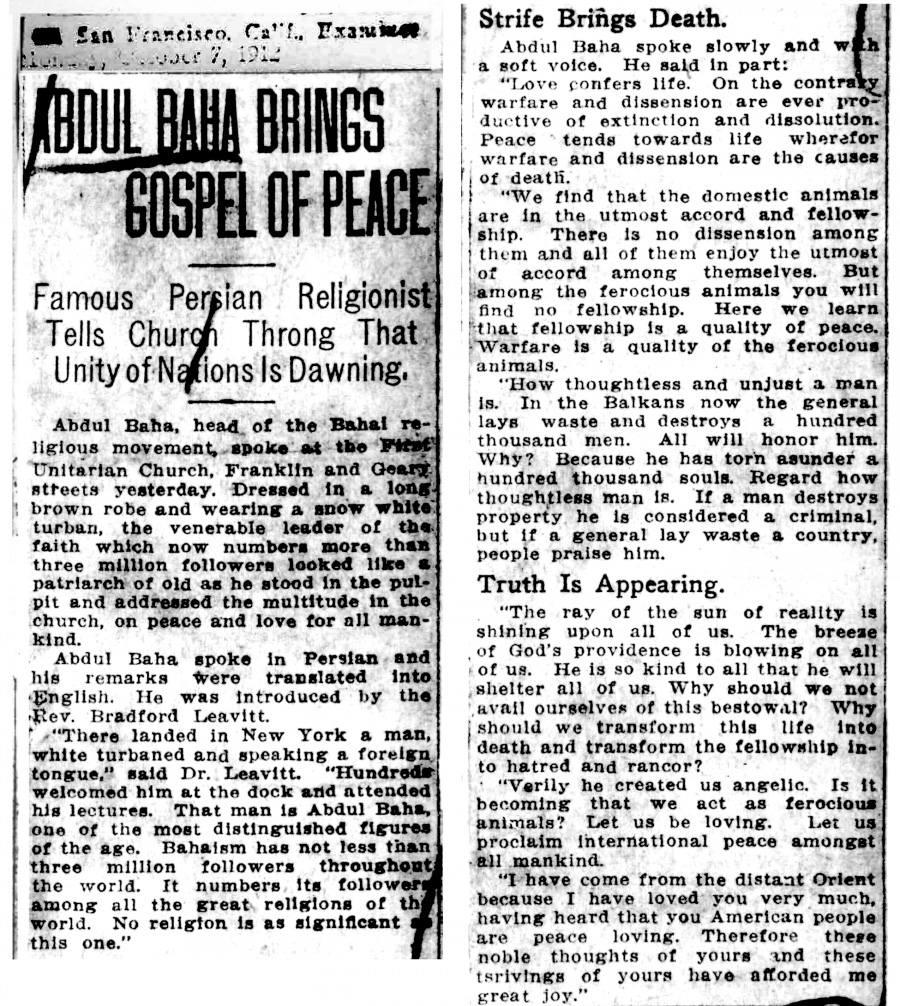

Keenly aware of the events transpiring in the world at large, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá viewed the establishment of universal peace as one of the most critical issues of the day. His writings and public talks outline the Bahá’í approach to peace and methods for its attainment and explain and illuminate the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh. They reflect a profound and sensitive understanding of the state of the world and demonstrate the relevance of the Bahá’í teachings to the alleviation of the human condition. The Bahá’í approach stresses a reliance on the constructive power of religion and on the forces of social and spiritual cohesion as a way to impact the world.1For a detailed discussion of the Bahá’í teachings on peace, see Hoda Mahmoudi and Janet A. Khan. A World Without War: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the Discourse for Global Peace (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing, 2020).

‘Abdu’l-Bahá saw in World War I a harrowing lesson of the human necessity for peace – and of the darkness that can ensue without peace. He knew and wrote extensively that nothing short of the establishment of the spiritual foundations for peace could result in lasting peace and security for humanity. In His written works, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá repeatedly draws our attention to the need for establishing the spiritual prerequisites for peace, requisites which, in turn, remove the barriers to peace, such as racial prejudice, sexism, economic inequalities, sectarianism, and nationalism.

That remarkable time in the history of the world provides the backdrop to the Tablets of the Divine Plan, a series of letters ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed to the Bahá’ís of North America. A study of these letters together with two detailed letters2Tablets to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/188605710 on peace addressed to the Executive Committee of the Central Organization for a Durable Peace at The Hague provides an opportunity to better understand the nature of universal peace as envisioned in the Bahá’í writings, the prerequisites of peace, and how peace can be waged. The Tablets of the Divine Plan set out a systematic strategy aimed at strengthening embryonic Bahá’í communities, founded on the principle of the oneness of humankind, and mobilizing their members to engage in activities associated with spreading the values of peace. The Tablets to The Hague are examples from among ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s tireless efforts to contribute to the most relevant discourses of His time and to engage like-minded individuals and groups throughout the world in the pursuit of peace.3Mahmoudi and Khan, World Without War.

A Power of Implementation

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s caveat that “the power of thought” depends on “its manifestation in action,”4‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Paris Talks. Available at www.bahai.org/r/361617663 is particularly relevant to the idea of peace. Consider! Nearly 20 million men, women and children were killed during the four years of World War I!

‘Abdu’l-Bahá took the principles of global peace revealed by Bahá’u’lláh and shaped them into a practical grand strategy for how to understand, practice, and pursue peace. Among the voluminous writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the fourteen letters of the Tablets of the Divine Plan outlined detailed instructions and systematic actions for the spread of the spiritual teachings of the Bahá’í Faith throughout the world. Their aim was the establishment of growing communities throughout the world that would embody the values of peace, would comprise the diverse populations of the human family, and would contribute to the spiritualization of the planet—a vision that was being promoted as the world was witnessing the horrors and sufferings of the war:

Black darkness is enshrouding all regions… all countries are burning with the flame of dissension…the fire of war and carnage is blazing throughout the East and the West. Blood is flowing, corpses bestrew the ground, and severed heads are fallen on the dust of the battlefield.5‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/713519310

‘Abdu’l-Bahá called on the recipients of the Tablets to arise and take action, establishing throughout the planet new communities founded on the spiritual principles of love, goodwill, and cooperation among humankind. Through such calls for acts of sacrificial service that arising to spread the divine teachings would entail, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was promoting an antidote to the social and spiritual illnesses that contribute to the conditions of war. He reminded the recipients of His letters of the power of spiritual forces to transform hatred, division, war, and destruction into love, unity, dignity, and the nobility of every human being. “Extinguish this fire,” He wrote, “so that these dense clouds which obscure the horizon may be scattered, the Sun of Reality shine forth with the rays of conciliation, this intense gloom be dispelled and the resplendent light of peace shed its radiance upon all countries.”6‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/577240123

‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained that if we desire peace in the world, we must begin by planting peace in our own hearts. This principle can be found throughout the writings of Bahá’u’lláh:

What is preferable in the sight of God is that the cities of men’s hearts, which are ruled by the hosts of self and passion, should be subdued by the sword of utterance, of wisdom and of understanding. Thus, whoso seeketh to assist God must, before all else, conquer, with the sword of inner meaning and explanation, the city of his own heart and guard it from the remembrance of all save God, and only then set out to subdue the cities of the hearts of others. 7Bahá’u’lláh. The Summons of the Lord of Hosts. Available at www.bahai.org/r/581531547

While ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sought to mobilize the Bahá’ís of North America to spread the unifying message of Bahá’u’lláh throughout the world, He also pursued numerous opportunities to introduce into the discourses of His time essential concepts and principles that would help the thinking of His contemporaries to evolve and assist humanity to move towards the realization of peace.

Indeed, in His letters to the Central Organization for a Durable Peace, written in 1919 and 1920 after the war’s conclusion, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gently but unequivocally challenged His audience to broaden its conception of peace. Specifically, in His first letter, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explored “many teachings which supplemented and supported that of universal peace,” such as the “independent investigation of reality,” “the oneness of the world of humanity,” and “the equality of women and men.” Some other related teachings of Bahá’u’lláh that were explained by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá included the following: “that religion must be the cause of fellowship and love,” “that religion must be in conformity with science and reason,” “that religious, racial, political, economic and patriotic prejudices destroy the edifice of humanity,” and “that although material civilization is one of the means for the progress of the world of mankind, yet until it becomes combined with Divine civilization, the desired result, which is the felicity of mankind, will not be attained.”8‘Abdu’l-Bahá. First Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/551373700 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá then reiterated His point, stating:

These manifold principles, which constitute the greatest basis for the felicity of mankind and are of the bounties of the Merciful, must be added to the matter of universal peace and combined with it, so that results may accrue. 9‘Abdu’l-Bahá. First Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/376814060

In the Second Tablet to the Hague, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá observed that for peace to be realized in the world, it would not be enough that people were simply informed about the horrors of war. “Today the benefits of universal peace are recognized amongst the people, and likewise the harmful effects of war are clear and manifest to all,” wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

But in this matter, knowledge alone is far from sufficient: A power of implementation is needed to establish it throughout the world.… It is our firm belief that the power of implementation in this great endeavour is the penetrating influence of the Word of God and the confirmations of the Holy Spirit.10‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Second Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/705335105

Abdu’l-Bahá asserted that it is through this power of implementation that “the compelling power of conscience can be awakened, so that this lofty ideal may be translated from the realm of thought into that of reality.” “It is clear and evident,” He explained, “that the execution of this mighty endeavour is impossible through ordinary human feelings but requireth the powerful sentiments of the heart to transform its potential into reality.” 11‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Second Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/705335105

Spiritual Foundations of Peace

Understanding ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approach to peace also demands we understand Bahá’u’lláh’s direct engagement with the world and His doctrinal declarations concerning the Bahá’í Faith. Bahá’u’lláh’s writings describe a “progressive revelation” of religion in which individual religions arise to meet the need of their times. Bahá’u’lláh stated that particular religions were entrusted with a message and a spirit that “best meet the requirements of the age in which” that religion appeared.12Bahá’u’lláh. Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. Available at www.bahai.org/r/757983498 In this context, religions are viewed as the gradual unfolding of one religion that is being renewed from age to age. The variations in the teachings of these religions are attributable to a world that is constantly changing and needing spiritual renewal and spiritual principles. Because “ancient laws and archaic ethical systems will not meet the requirements of modern conditions,” then, as a new religion takes shape, new sets of laws and principles are revealed to humanity and new spiritual beliefs must always emerge.13‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/841894042

Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation calls on individuals to internalize spiritual principles and express them through actions. He proclaimed “to the world the solidarity of nations and the oneness of humankind.”14‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/955162073 He described “a human race conscious of its own oneness.”15Bahá’í International Community, Who is Writing the Future? (New York: Office of Public Information, 1999), V.2. Complex concepts such as human oneness and the global order were transformed from utopian ideals to spiritual commands of the highest order; the Bahá’í writings unfold and clarify how such commands might be fulfilled. Bahá’u’lláh’s vision also details the need for the construction of a World Order, an order comprising administrative institutions at the local, regional, national, and international levels. Such institutions, among other things, serve as channels for the application of spiritual principles. As the institutions evolve over decades and centuries, a new world order will eventually produce the conditions conducive to global peace. Yet, even as the Bahá’í writings envision a long-term process of global transformation and maturation of the human race, they also assert that change will also arise from individual and collective efforts at the grassroots of society. In exploring the creative Word and learning to apply it to their individual and collective lives, individuals are spiritually transformed from the inside-out, and they contribute to the transformation of communities, institutions, and society at large.

In describing the Bahá’í Faith’s strong prohibition on waging war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, stated that Bahá’u’lláh “abrogated contention and conflict, and even rejected undue insistence. He exhorted us instead to ‘consort with the followers of all religions in a spirit of friendliness and fellowship.’ He ordained that we be loving friends and well-wishers of all peoples and religions and enjoined upon us to demonstrate the highest virtues in our dealings with the kindreds of the earth….What a heavy burden was all that enmity and rancour, all that recourse to sword and spear!” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote of the impact of war on humanity. “Conversely, what joy, what gladness is imparted by loving-kindness!”16‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Light of the World. Available at www.bahai.org/r/408465671

‘Abdu’l-Bahá viewed peace as a central facet of the work of the Bahá’í Faith. There was no separating peace from the Bahá’í Faith, nor was there any separation between the Faith and peace. Peace was both medium and message, and the Bahá’í Faith itself was the vehicle for establishing peace. He explained, in His Second Tablet to the Hague, that the followers of Bahá’u’lláh were actively engaged in the establishment of peace, because their

desire for peace is not derived merely from the intellect: It is a matter of religious belief and one of the eternal foundations of the Faith of God. That is why we strive with all our might and, forsaking our own advantage, rest, and comfort, forgo the pursuit of our own affairs; devote ourselves to the mighty cause of peace; and consider it to be the very foundation of the Divine religions, a service to His Kingdom, the source of eternal life, and the greatest means of admittance into the heavenly realm.”17‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Tablets to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/749353064

Strategic Plan for the Achievement of Peace

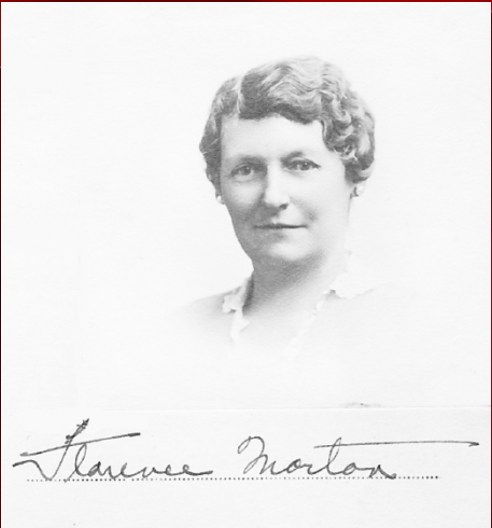

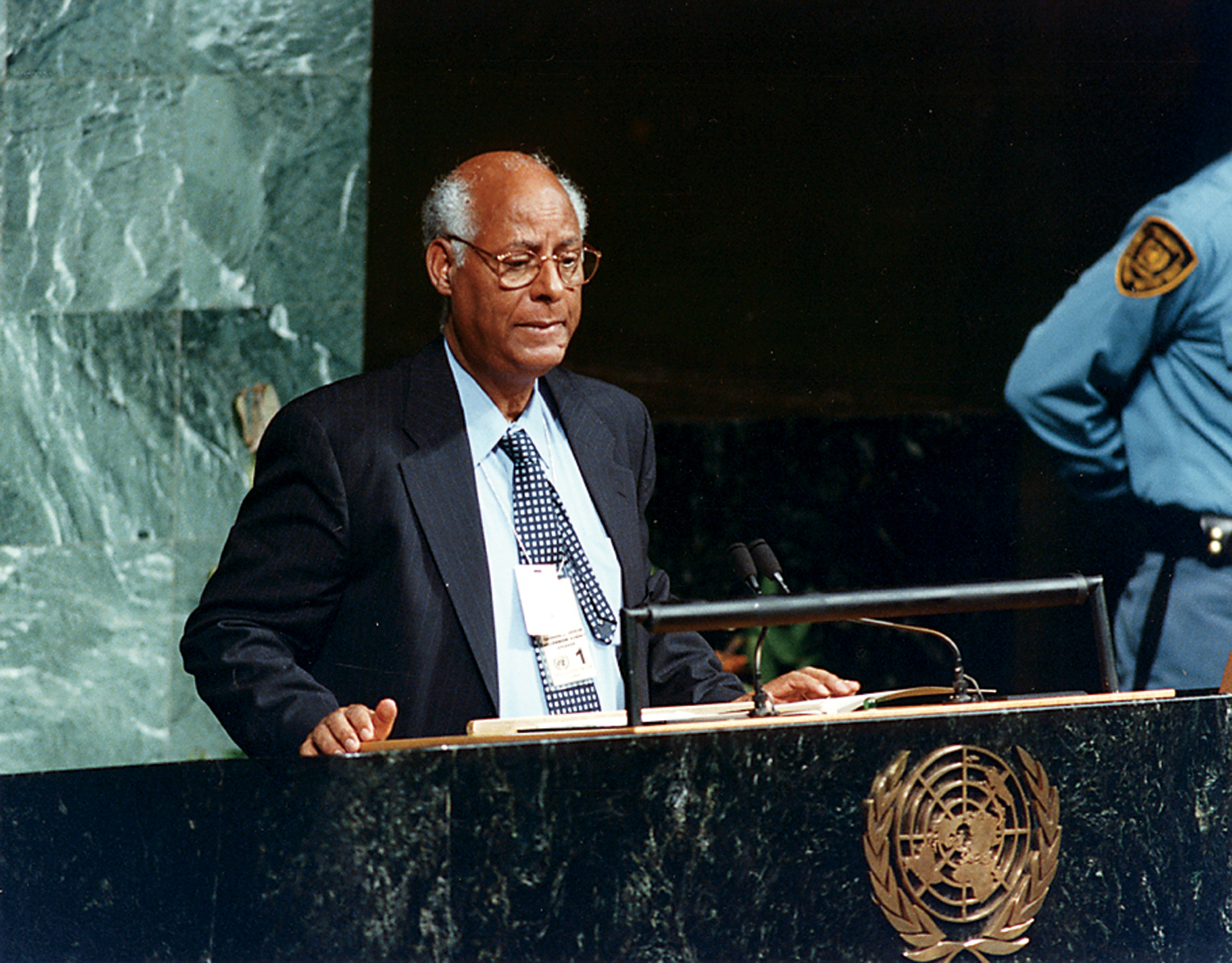

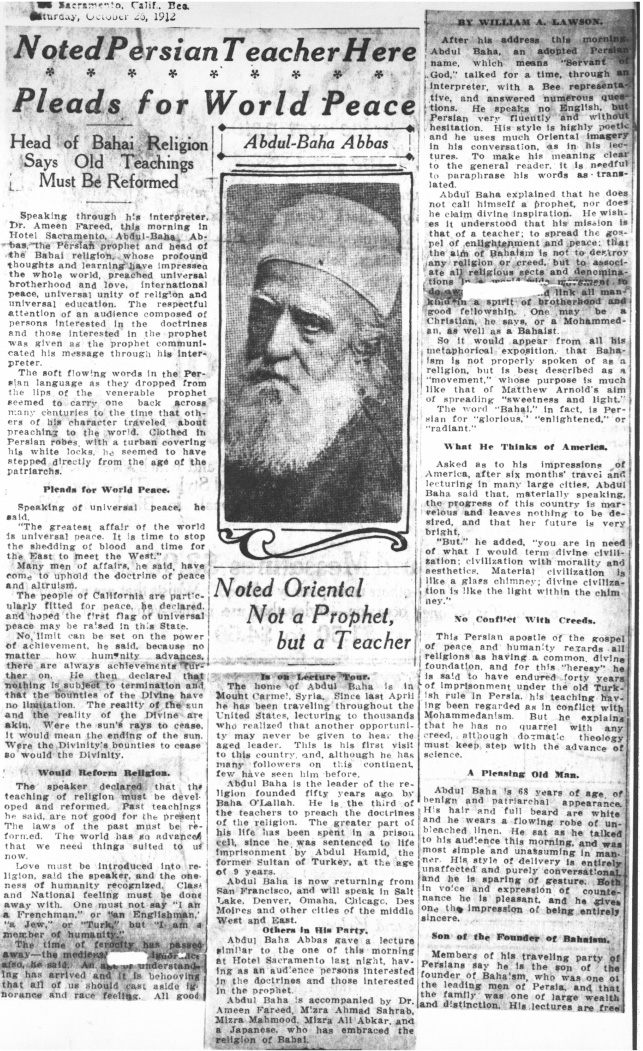

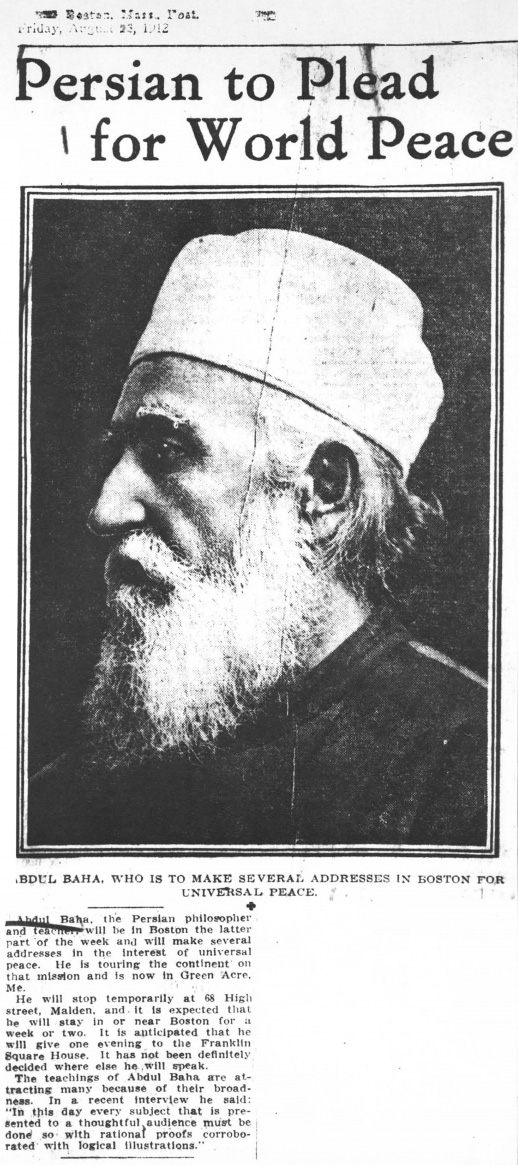

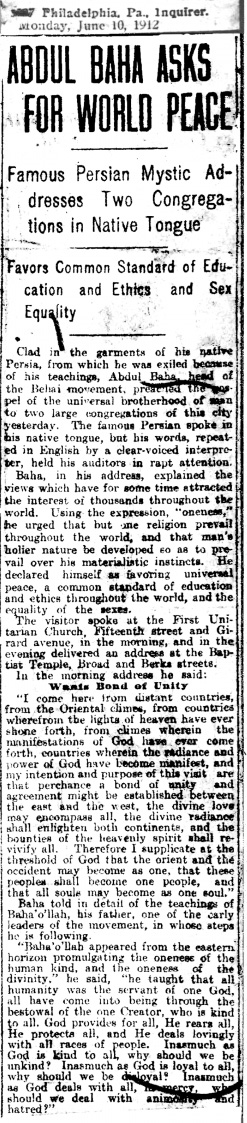

‘Abdu’l-Bahá dedicated His life to the advancement of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh and to the establishment of universal peace. His peace activities in the West include many talks given in Europe and North America. He had close contact with civic leaders and social activists and participated in the 1912 Lake Mohonk Conference on Peace and Arbitration in upstate New York attended by over 180 prominent people from the United States and other countries. He addressed a variety of American women’s organizations, gave presentations at universities and colleges, spoke in Chicago at the NAACP’s annual conference, and gave lectures at churches and synagogues.

Yet for all His courageous activities, and all the efforts of the Bahá’ís, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was greatly saddened by the world’s apparent indifference to Bahá’u’lláh’s call for global peace and to the efforts He Himself had made in the course of His travels. Shoghi Effendi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s grandson and His appointed successor, wrote: “Agony filled His soul at the spectacle of human slaughter precipitated through humanity’s failure to respond to the summons He had issued, or to heed the warnings He had given.”18Shoghi Effendi. God Passes By. Available at www.bahai.org/r/986414751

Given the turbulent condition of the world and the dangers facing humankind, He devised a detailed strategic plan to address the situation and to assign responsibility for its implementation. His plan, devised in 1916 to 1917 and set out in fourteen letters, known collectively as the Tablets of the Divine Plan, was entrusted to the members of the Bahá’í community in the United States and Canada. The pivotal goal of the Tablets of the Divine Plan is directly associated with the long-range process that will lead to the achievement of peace in the world as envisaged in Bahá’u’lláh’s writings.

Designated as “the chosen trustees and principal executors of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Divine Plan,”19Shoghi Effendi. This Decisive Hour. Available at www.bahai.org/r/194317153 the North American Bahá’ís were called upon to assume a prominent role in taking the message of Bahá’u’lláh to all the countries of the world and for effecting the transformation in values necessary for the emergence of a world order characterized by justice, unity, and peace. This great human resource – the body of willing believers in the West – was notable for its enthusiasm, determination, and deep commitment to Bahá’u’lláh’s vision for change. These communities were ideal incubators for the processes of peace.

At the time the messages of the Tablets of the Divine Plan were being written, North American Bahá’ís comprised but a small percentage of the total Bahá’ís in the world (though many had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in 1912). Commenting on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s choice of the North American Bahá’ís and the link between World War I and the Tablets of the Divine Plan, Shoghi Effendi indicated that the Divine Plan “was prompted by the contact established by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Himself, in the course of His historic journey, with the entire body of His followers throughout the United States and Canada. It was conceived, soon after that contact was established, in the midst of what was then held to be one of the most devastating crises in human history.”20Shoghi Effendi. This Decisive Hour. Available at www.bahai.org/r/257510249 Shoghi Effendi offered further comment concerning the historic bond between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the North American community: “This is the community,” he reminded us,

which, ever since it was called into being through the creative energies released by the proclamation of the Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, was nursed in the lap of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s unfailing solicitude, and was trained by Him to discharge its unique mission through the revelation of innumerable Tablets, through the instructions issued to returning pilgrims, through the despatch of special messengers, through His own travels at a later date, across the North American continent, through the emphasis laid by Him on the institution of the Covenant in the course of those travels, and finally through His mandate embodied in the Tablets of the Divine Plan.21Shoghi Effendi. God Passes By. Available at www.bahai.org/r/256927469

It is clear that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was aware of the potential capacity of the North American Bahá’ís to carry out the task with which they had been entrusted. His extensive travels in North America afforded the opportunity to assess, at first hand, the spiritual, social, and political environment of the continent and to appreciate the freedoms – intellectual, artistic, political, and, particularly, the religious freedom—inherent in North American society. And it is also apparent that He understood the spiritual possibilities of the West and the desire of women and men to seek a fuller expression of all things – of themselves, of their society, of the world.

Significance of the Tablets of the Divine Plan

As described above, the Tablets of the Divine Plan constitute the charter for the propagation of the Bahá’í Faith and outline ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s plan for the spiritual regeneration of the world. The letters therein set out the prerequisites for peace and assign responsibility to the North American believers “to plant the banner of His Father’s Faith . . . in all the continents, the countries and islands of the globe.”22Shoghi Effendi. God Passes By. Available at www.bahai.org/r/552193552 They focus on the work of promulgating and implementing Bahá’u’lláh’s salutary message of unity, justice, and peace in a systematic and orderly manner. They represent a strategic intervention put in place by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to ensure the ongoing and systematic dissemination of the values of peace and the promotion of activities associated with moral and social advancement. They describe a spiritually based approach to peace that is pragmatic, long-term, flexible, and durable.

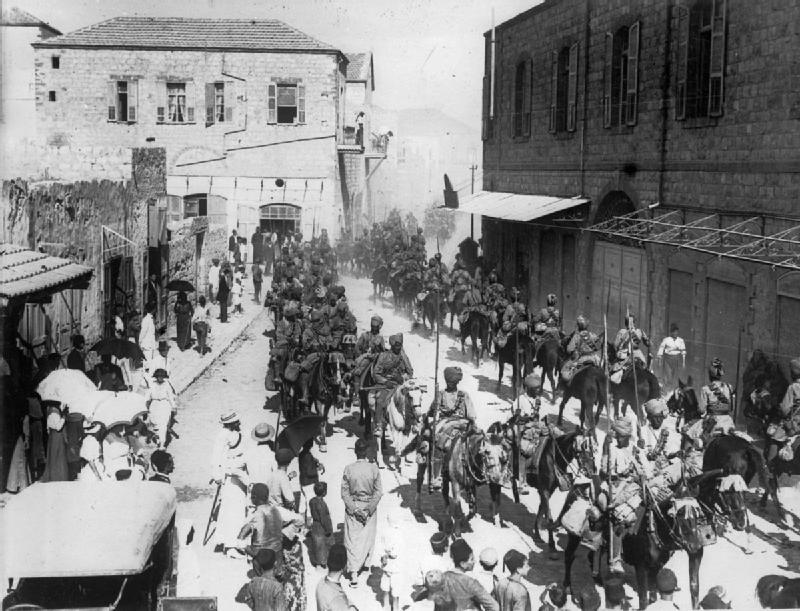

In those darkest days of World War I, the means of communication between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palestine (then under the rule of the Ottoman Empire) and the community of His followers around the world were disrupted and, for a period, severed. The first eight Tablets were written in the spring of 1916, and the second group was penned during the spring of 1917. The first group did not arrive in North America until the fall of 1916, while the delivery of the remaining Tablets was delayed until after the cessation of hostilities.23Amin Banani. Foreword to Tablets of the Divine Plan. (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1993), xxi.

The Great War of 1914-1918 rocked the very foundations of society and dramatically changed the shape of the world. The historian Margaret MacMillan provides a telling summary of the impact of the War:

Four years of war shook forever the supreme self-confidence that had carried Europe to world dominance. After the western front Europeans could no longer talk of a civilizing mission to the world. The war toppled governments, humbled the mighty and overturned whole societies. In Russia the revolutions of 1917 replaced tsarism, with what no one yet knew. At the end of the war Austria-Hungary vanished, leaving a great hole at the centre of Europe. The Ottoman empire, with its vast holdings in the Middle East and its bit of Europe, was almost done. Imperial Germany was now a republic. Old nations—Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia—came out of history to live again and new nations—Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia—struggled to be born.24Margaret MacMillan. Peacemakers: Six Months that Changed the World. (London: John Murray, 2001), 2.

The Tablets captured the mood of the day—the complex fusion of anxiety and despair, the burning desire to end a war more brutal than any the world had ever known, and a desire for a new approach to peaceful existence. Addressing this heartfelt yearning, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá offered a contrasting vision of how the world might be if it lived in harmony:

This world-consuming war has set such a conflagration to the hearts that no word can describe it. In all the countries of the world the longing for universal peace is taking possession of men. There is not a soul who does not yearn for concord and peace. A most wonderful state of receptivity is being realized. This is through the consummate wisdom of God, so that capacity may be created, the standard of the oneness of the world of humanity be upraised, and the fundamental of universal peace and the divine principles be promoted in the East and the West.25‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/500285326

In another Tablet, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reflected on the impact of World War I on humankind and offered a context for understanding the “wisdom of this war”:

In short, after this universal war, the people have obtained extraordinary capacity to hearken to the divine teachings, for the wisdom of this war is this: That it may become proven to all that the fire of war is world-consuming, whereas the rays of peace are world-enlightening. One is death, the other is life; this is extinction, that is immortality; one is the most great calamity, the other is the most great bounty; this is darkness, that is light; this is eternal humiliation and that is everlasting glory; one is the destroyer of the foundation of man, the other is the founder of the prosperity of the human race.26‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/828798977

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s response to war, as set out in the Tablets of the Divine Plan, went far beyond providing an alternative vision. He called for constructive mobilization consistent with the local situation. For example, tapping into peoples’ receptivity to new ideas resulting from the sufferings associated with war, He directed the Bahá’ís to take steps to spread Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, and He set out other concrete actions that could be immediately taken. These activities aimed not only to enlarge the Bahá’í community but were considered essential to spreading the values of peace in the wider society. To this end, He invited “a number of souls” to “arise and act in accordance with the aforesaid conditions, and hasten to all parts of the world.…Thus in a short space of time, most wonderful results will be produced, the banner of universal peace will be waving on the apex of the world and the lights of the oneness of the world of humanity may illumine the universe.”27‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/998358260

The Tablets of the Divine Plan underlined the contribution of religion to individual and social development. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated:

Consider how the religions of God served the world of humanity! How the religion of Torah became conducive to the glory and honor and progress of the Israelitish nation! How the breaths of the Holy Spirit of His Holiness Christ created affinity and unity between divergent communities and quarreling families! How the sacred power of His Holiness Muḥammad became the means of uniting and harmonizing the contentious tribes and the different clans of Peninsular Arabia—to such an extent that one thousand tribes were welded into one tribe; strife and discord were done away with; all of them unitedly and with one accord strove in advancing the cause of culture and civilization, and thus were freed from the lowest degree of degradation, soaring toward the height of everlasting glory!28‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/191427232

Within this context, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá affirmed that the Bahá’í community’s historic mission was at heart a spiritual enterprise, and He illustrated the capacity of the community to unite peoples of different background. He wrote:

Consider! The people of the East and the West were in the utmost strangeness. Now to what a high degree they are acquainted with each other and united together! How far are the inhabitants of Persia from the remotest countries of America! And now observe how great has been the influence of the heavenly power, for the distance of thousands of miles has become identical with one step! How various nations that have had no relations or similarity with each other are now united and agreed through this divine potency! Indeed to God belongs power in the past and in the future! And verily God is powerful over all things!29‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/205096335

The community-building activities initiated by the Bahá’ís at the behest of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the diversity of the Faith’s emerging community constitute a powerful means to engage the interest and attract the collaboration of like-minded people who are also committed to the cause of enduring social change and are willing to work for the creation of a culture of peace.

The vision of the Tablets of the Divine Plan is a vision that regards all human beings as being responsible for the advancement of civilization. The Bahá’í Faith looks to ensure such advancement is possible by highlighting the pathways of unity. To initiate the processes of individual and social transformation, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá calls on his followers to embrace a series of tasks – in a sense, to get to work – so that they might

occupy themselves with the diffusion of the divine exhortations and advices, guide the souls and promote the oneness of the world of humanity. They must play the melody of international conciliation with such power that every deaf one may attain hearing, every extinct person may be set aglow, every dead one may obtain new life and every indifferent soul may find ecstasy. It is certain that such will be the consummation.30‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/258989901

Humankind is asked to flee “all ignorant prejudices” and work for the good of all. In the West, individuals are charged to commit to “the promulgation of the divine principles so that the oneness of the world of humanity may pitch her canopy in the apex of America and all the nations of the world may follow the divine policy.”31‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/785288640

The great changes described in the Tablets will evolve slowly. For though the Tablets call for a time when “the mirror of the earth may become the mirror of the Kingdom, reflecting the ideal virtues of heaven,”32‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/904315062 translating this poetic vision into a concrete plan will take time. But this delay is not cause for slowing the activities of peace, rather the scale of change demands a systematic approach to peace.33‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Ibid 3.3 For instance, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá lists countries by name and specifies the order in which tasks are to be completed.34‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Ibid., ¶6.11, ¶6.4, and ¶6.7.

But along with all His specificity, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also describes a lofty vision meant to inspire. He calls upon His followers to become “heavenly farmers and scatter pure seeds in the prepared soil,” promises that “throughout the coming centuries and cycles many harvests will be gathered,” and asks followers to “consider the work of former generations. During the lifetime of Jesus Christ, the believing, firm souls were few and numbered, but the heavenly blessings descended so plentifully that in a number of years countless souls entered beneath the shadow of the Gospel.”35‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/434173994

Looking Ahead

Written just over a century ago during one of humanity’s darkest hours, the Tablets of the Divine Plan “set in motion processes designed to bring about, in due course, the spiritual transformation of the planet.”36Universal House of Justice. From a letter to the Bahá’ís of the World dated 21 March 2009. Available at www.bahai.org/r/288100650 These letters continue to guide Bahá’ís as they pursue the current Divine Plan under the authority of the Universal House of Justice, the international governing council of the Bahá’í Faith, and they serve as an inspiration to many others who study them. In fourteen letters, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá laid out a charter for the teaching, building, and communal activities that define the Bahá’í theatre of action. While its long-term vision encompasses all humanity, the Divine Plan’s execution is tied to the Bahá’í community’s spiritual evolution and the development of its administrative institutions. It is also tied to humanity’s receptivity and willingness to pursue peace.

Today, Bahá’ís throughout the world are actively engaged in the application of the Divine Plan through a long-term process of community building inspired by the principle of the oneness of humankind. Embracing an outward-looking orientation, Bahá’ís maintain that to systematically advance a material and spiritual global civilization, the contributions of innumerable individuals, groups, and organizations is required for generations to come. The process of community building that is finding expression in Bahá’í localities throughout the world is open to all peoples regardless of race, gender, nationality, or religion.

In these communities, Bahá’ís aspire to develop patterns of life and social structures based on Bahá’u’lláh’s principles. Throughout the process they are learning how to strengthen community life based on spiritual principles including the prerequisites for the establishment of global peace as identified in the Bahá’í writings. The Plan, in both urban and rural settings, is comprised of an educational process where children, youth, and adults explore spiritual concepts, gain capacity, and apply them to their own distinct social environment. As individuals participate in this ongoing process of community building, they draw insights from science and religion’s spiritual teachings toward gaining new knowledge and insights.

The acquisition of new knowledge is continually applied to nurturing a community environment that is free from prejudice of race, class, religion, nationality, and strives to achieve the full equality of women in all the affairs of the community as well as the society at large. A natural outcome of this transformative learning process of spiritual and material education is involvement in the life of society. In this regard, Bahá’ís are engaged in two interconnected areas of action: social action and participation in the prevalent discourses of society. Social action involves the application of spiritual principles to social problems in order to advance material progress in diverse settings. Second, in diverse settings, Bahá’í institutions and agencies, in addition to individuals and organizations, whether academic or professional, or at national and international forums, also participate in important discourses prevalent in society with the goal of exploring the solutions to social problems and contributing to the advancement of society. Aware of the complex challenges that lie ahead of them in this work, Bahá’ís are working jointly with others, convinced of the unique role that religion offers in the construction of a spiritual global order.37For more detailed information please refer to message dated 18 January 2019 from the Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the World. Available at www.bahai.org/r/537332008 ; Riḍván 2021 message from the Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the World. Available at wwww.bahai.org/r/750707520

Stressing the vital significance of striving to enhance the learning processes associated with the implementation of peace, a recent message addressed to Bahá’ís and their collaborators, observed that

none who are conscious of the condition of the world can refrain from giving their utmost endeavour… The devoted efforts that you and your like-minded collaborators are making to build communities founded on spiritual principles, to apply those principles for the betterment of your societies, and to offer the insights arising—these are the surest ways you can hasten the fulfillment of the promise of world peace.38Universal House of Justice. From a message to the Bahá’ís of the World dated 18 January 2019. Available at www.bahai.org/r/276724432

The Divine Plan continues to unfold over the decades as the collective capacity of the Bahá’í community grows in tandem with the world’s openness to change. Implementation of the Plan continues and will continue so that the world might achieve “the advent of that Golden Age which must witness the proclamation of the Most Great Peace and the unfoldment of that world civilization which is the offspring and primary purpose of that Peace.”39Shoghi Effendi. Citadel of Faith: Messages to America, 1947-1957. Available at www.bahai.org/r/688620126

In October 1911, as the world teetered towards collapse and the prospects of war loomed large, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá delivered a speech in Paris to a group of individuals who were seeking creative solutions to the issues of the day. He spoke about the pragmatic relationship between “true thought” and its application. “If these thoughts never reach the plane of action,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained, “they remain useless: the power of thought is dependent on its manifestation in deeds.”40‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Paris Talks. Available at www.bahai.org/r/184033132

In this paper we explore ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s active promotion of the broad vision of peace set out in the teachings of the Bahá’í Faith and examine His contributions to mobilizing widespread support for the practice of peace. The realization of peace, as outlined in the Bahá’í writings and elucidated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, is dependent on spiritual thoughts based on spiritual virtues expressed through human deeds.

By 1914, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was well known in many parts of the globe for His life of service to humanity. In the Holy Land, where He had lived most of His adult life, He was revered for His service to the poor and needy in the community and for His engagement in the discourses of the day with local and regional dignitaries. His lengthy sojourns in Egypt before and after His historic visits to Europe and North America also attracted considerable attention, earning Him even more admirers from all walks of life. His travels in the West, from which He had only recently returned in early 1914, have been particularly well-documented; in both formal and informal settings and to diverse audiences, His explications of the Teachings of His Father, Bahá’u’lláh, in the context of the urgent promotion of global peace, made Him a unique Figure on the world stage. In the war years, He would win widespread acclaim for helping to avert a famine in His home region of Haifa and ‘Akká. And for many around the world, the example of His life and His voluminous Writings were and continue to be sources of guidance and elucidation.

However, rather less well known today is ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s sustained promotion of modern education in the Middle East. Perhaps most striking in this regard is how, over a period of several years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged and nurtured a group of Bahá’í students in Beirut to pursue higher education in a way that was coherent with the students’ identities as Bahá’ís.

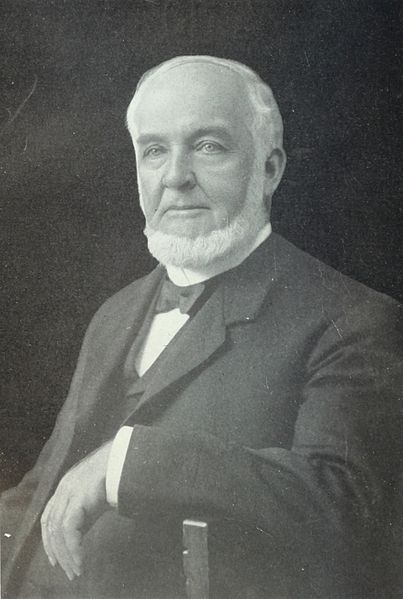

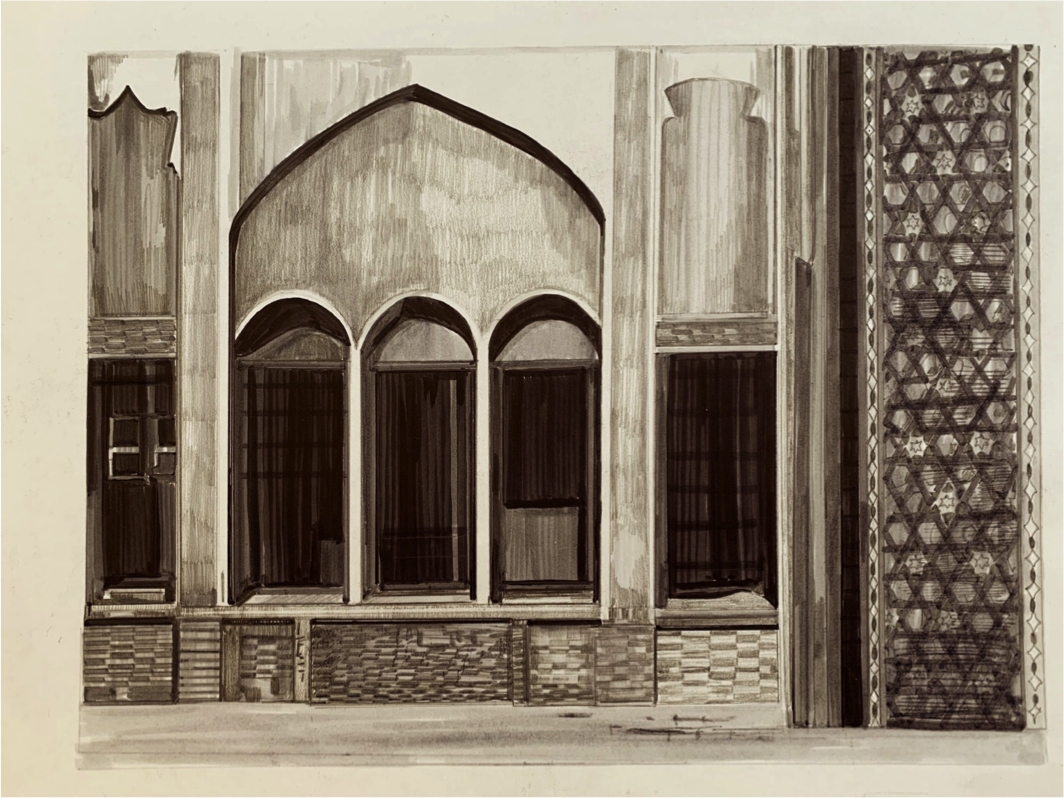

Among ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s many visitors in early 1914 was Howard Bliss, the president of the Syrian Protestant College (SPC), an institution with which ʻAbdu’l-Bahá had maintained a longstanding relationship and at which a group of Bahá’í students had become an established presence by the time of Bliss’s visit that February.1H.M Balyuzi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh (Oxford: George Ronald, 1973), 405. Bliss, an American who had grown up on the campus of the college in Beirut (his father, Daniel Bliss, was the college’s first president) and who spoke fluent Arabic, was visiting, in part, to arrange for the Bahá’í students to spend their upcoming spring break in Haifa in the vicinity of the Shrines of Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb, affording them an opportunity to meet and learn from ʻAbdu’l-Bahá. But the conversation between ʻAbdu’l-Bahá and Bliss extended to topics of pressing concern for the former. Much as He had done on numerous occasions during His travels, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá encouraged Bliss to foster in his students “principles” such as the “oneness of the world of humanity,” among others, so that their education could be directed toward “universal peace.”2Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98, http://sotwbnewsinfo.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/sotw/searchable_pdfs/SotW_Vol-01%20(Mar%201910)-Vol-10%20(Mar%201919).pdf See also “Zeine on Modern Education,” Al-Kulliyah, Winter 1973, 15, American University of Beirut/Library Archives.

Bliss’s receptivity to ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s remarks and encouragement was evident in a speech Bliss gave just ten days later. On 25 February, in a meeting with a group of students that was representative of the school’s rich diversity, Bliss urged it to include the “establishing of universal peace” as one of its “missions.”3Al-Kulliyah, March 1914, No. 5, 151, American University of Beirut/Library Archives ʻAbdu’l-Bahá and Bliss’s exchange, indeed, was emblematic of the larger conversation the Bahá’í community and the college had been having for several years, a conversation centering on the college’s self-styled “experiment in religious association” to which the Bahá’í students had been striving to contribute.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá and Modern Education

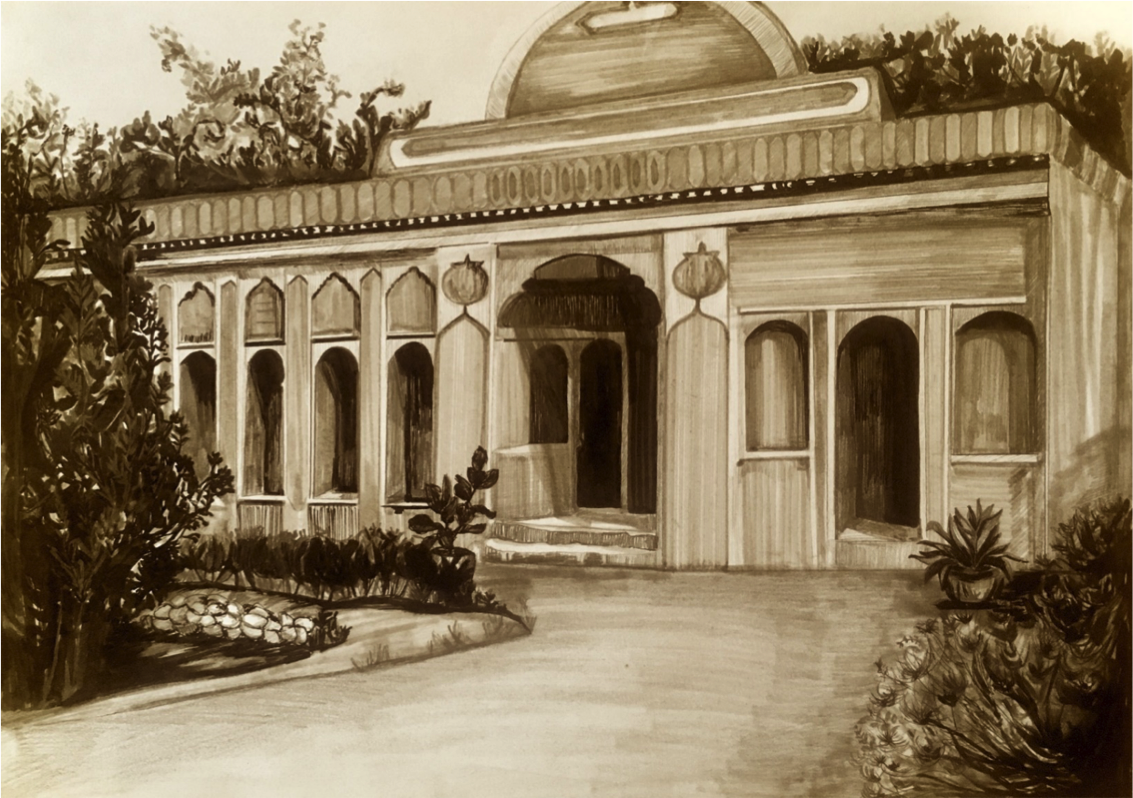

The Syrian Protestant College was founded in 1866 and formally renamed the American University of Beirut (AUB) in 1920. Long before any Bahá’í students had enrolled there, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in an 1875 treatise known today as The Secret of Divine Civilization4Available at www.bahai.org/r/093729958 encouraged the establishing of modern schools in His native Persia, advocating for the “extension of education, the development of useful arts and sciences, the promotion of industry and technology.” 5‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Secret of Divine Civilization. Available at www.bahai.org/r/568414401 Education, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá asserted, should uplift individuals for the ultimate purpose of benefiting society. Over the following decades, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was instrumental in the establishment of dozens of schools throughout His native land; notably, these schools, including many for girls, welcomed students of all faiths.6See Soli Shahvar, The Forgotten Schools: The Baha’is and Modern Education in Iran, 1899-1934 (London: Taurus Academic Studies, 2009).

‘Abdu’l-Bahá personally supervised such initiatives in His local community in ‘Akká as well. In 1903, for example, about twenty children from the Bahá’í community were assembled for classes in English, Persian, math, and other subjects including practical instruction in trades like carpentry, shoemaking, and tailoring.7Youness Afroukhteh, Memories of Nine Years in ‘Akká, Trans. by Riaz Masrour (Oxford: George Ronald, 2003), 159-60. Many of these students continued their studies at local schools, such as a French one in Haifa.8Riaz Khadem, Shoghi Effendi in Oxford and Earlier (Oxford: George Ronald, 1999), 2. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá encouraged students such as these, including His own grandchildren, to continue their education at colleges and universities, the closest of which was SPC; Shoghi Effendi, His eldest grandson and successor as Head of the Bahá’í Faith, graduated from SPC in 1917.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá repeatedly qualified his support of such schools with the condition that they attend to the whole student and produce graduates who had progressed not only scientifically but also morally. During his visit to North America in 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at Columbia and Stanford universities, praising the value of the scientific education they provided while also emphasizing the necessity of “spiritual development…the most important principle [of which] is the oneness of the world of humanity, the unity of mankind, the bond conjoining East and West, the tie of love which blends human hearts.”9‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912. Available at www.bahai.org/r/650712298

By this time, Bahá’í students from Haifa and ‘Akká, as well as Persia, Egypt, and Beirut, had attended SPC for about a decade, in increasing numbers over the previous few years. There were no comparable institutions in their own countries, and attending universities in Europe or America was not yet practical for most. As SPC became a popular choice, the prospect of joining an existing group of Bahá’í students was an additional attraction. A sizable group of students as well attended the Université Saint-Joseph (USJ), also in Beirut. Together, they constituted a single coherent group, meeting together, visiting each other, and collaborating, for example, in the activities of the “Society of the Bahá’í Students of Beirut,” which was formed in 1906.10Zeine N. Zeine, “The Program of the Society of Bahá’í Students of Beirut 1929-1930” (unpublished report, n.d.) ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Himself visited SPC during at least one of his visits to Beirut in 1880 and 1887.11Necati Alkan, “Midhat Pasha and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in ‘Akka: the Historical Background of the Tablet of the Land of Bā,” Baha’i Studies Review 13 (2005): 6-7, https://bahai-library.com/pdf/a/alkan_midhat_pasha_abdulbaha.pdf

The Bahá’í students’ engagement with educational institutions like SPC was very much framed in the terms ʻAbdu’l-Bahá had been setting forth for many years, perspectives inspired by the Teachings of His Father, Bahá’u’lláh. One such Teaching was the harmony of science and religion; as noted, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was calling for education to attend to the building of character as well as the shaping of intellects. This was a matter of intense interest at the college as well. While colleges in America had moved away from direct religious instruction, at SPC, there was still an effort to provide it.12Betty S. Anderson, The American University of Beirut: Arab Nationalism and Liberal Education (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 38. Around the time of ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s first visit, the faculty and missionaries associated with SPC had become sharply divided over just how to reconcile this religious education with the school’s scientific training. This rift had only deepened over the decades even as the younger Bliss had taken the college in increasingly “secular,” or liberal, directions. By 1908, the college’s course catalogue framed its approach in decidedly liberal terms, asserting that the “primary aim” of the curriculum is to “to develop the reasoning faculties of the mind, to lay the foundations of a thorough intellectual training, to free the mind for independent thought.”13Anderson, American University of Beirut, 52. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was supportive of the college’s efforts in this regard. As He Himself recorded in conversation with other visitors a week after Bliss’s visit:

The American College at Beirut is carrying on a sacred mission of education and enlightenment and every lover of higher culture and civilization must wish it a great success…Years ago I went to Beirut, and visited the College in its infancy. From that time on I have praised the liberalism of this institution whenever I found an opportunity.14Earl Redman. Visiting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Vol. 2: The Final Years, 1913-1921 (Oxford: George Ronald, 2021), 24-5.

Yet Bliss and others were intent on maintaining the Christian identity of the college. Heavily influenced by the Social Gospel and Progressive movements, Bliss’s conception of religious education “melded religion, character, and social service”15Anderson, American University of Beirut, 67. and, in his words, sought to “set so high, so noble, so broad, so ecumenical a type of Christianity before our students” as to inspire their education and future services to society.16Anderson, American University of Beirut, 64.

Howard Bliss presumably had this project in mind when, on 15 February 1914, he asked ʻAbdu’l-Bahá for His thoughts on “ideal” education.17“Zeine,” Al-Kulliyah, 15. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s response set forth “three cardinal principles.” These principles affirm the need for unfettered intellectual inquiry in education; however, they also call for the moral and ethical development of students and their reorientation toward a broadly conceived mission of service to humanity. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s comments were as follows:

In this age the college which is dominated by a denominational spirit is an anomaly, and is engaged in a losing fight. It cannot long withstand the victorious forces of liberalism in education. The universities and colleges of the world must hold fast to three cardinal principles.

First: Whole-hearted service to the cause of education, the unfolding of the mysteries of nature, the extension of the boundaries of pure science, the elimination of the causes of ignorance and social evils, a standard universal system of instruction, and the diffusion of the lights of knowledge and reality.

Second: Service to the cause of morality, raising the moral tone of the students, inspiring them with the sublimest ideals of ethical refinement, teaching them altruism, inculcating in their lives the beauty of holiness and the excellency of virtue and animating them with the excellences and perfections of the religion of God.

Third: Service to the oneness of the world of humanity; so that each student may consciously realize that he is a brother to all mankind, irrespective of religion or race. The thoughts of universal peace must be instilled into the minds of all scholars, in order that they may become the armies of peace, the real servants of the body politic – the world. God is the Father of all. Mankind are His children. This globe is one home. Nations are the members of one family. The mothers in their homes, the teachers in the schools, the professors in the college, the presidents in the universities, must teach these ideals to the young from the cradle up to the age of manhood.18Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s vision for education, as expressed above, included an implicit repudiation of social Darwinism, a theory which in the decades between His visit to SPC and His 1914 meeting with its college president had become increasingly popular. Ironically, while conservative thinkers initially rejected Darwin’s scientific theory of evolution, they later embraced its implications for society, when they associated a certain conception of progress as connected with “dominant” races and civilizations, that is, white and European ones.19Norbert Scholz, “Foreign Education and Indigenous Reaction in Late Ottoman Lebanon: Students and Teachers at the Syrian Protestant College” (PhD diss., Georgetown University, 1997), 233. The more liberal wing at the college also conflated its approach to Protestant education with “Americanism.”20Anderson, American University of Beirut, 57. As one commentator has put it, the college was sending the message that only “America and Protestantism had the tools for this progressive future.”21Anderson, American University of Beirut, 89.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá, however, urged Bliss to encourage his students to see themselves as serving the higher interests of humanity, not the particular ones of race or nation. In October of 1912, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá had implored assembled students, faculty, and staff at Stanford University along much the same lines, explaining that “the law of the survival of the fittest” did not apply to humanity.22‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/055943431 Acceding to such a law would be similar to allowing nature to remain uncultivated and unfruitful. Human progress, then, required education in the “ideal virtues of Divinity,” for humanity is inherently “lofty and noble” and “specialized” to “render service in the cause of human uplift and betterment.”23‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/935144964

Responding to a Crisis at the College

At the time of Bliss’s visit, a major controversy was raging at the college: the question of mandatory attendance at the school’s religious services. The college’s religious requirements had relaxed over the years and, partly as a result, the school had begun to attract a more diverse student body, not only Christians from various denominations but also more Muslims, Jews, Druze, and Bahá’ís. Spurred on by the Young Turk revolution of 1908 which, among others, advocated for religious freedom and equality, in early 1909, the majority of the Muslim students refused to attend Christian religion services and Bible classes, presenting a petition to the faculty a few days later requesting that such attendance become voluntary.24Stephen B. L Penrose, That They May Have Life: The Story of the American University of Beirut 1866-1941. (Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1970; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1941) 134-35. In addition to widespread opposition from Jewish students as well, the college also faced opposition from the local Muslim community, the Ottoman authorities, and American diplomats. While making some concessions to the striking students, the college largely withstood the pressure, and the mandate remained until 1915, when an Ottoman law made attendance voluntary. Bliss’s 1914 visit, in fact, was part of a tour of the region in which Bliss engaged with a number of civil and religious leaders in order to defend the college’s approach to religious education.

It was in this particular context that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s comments to Bliss about the “cardinal principles” of education were made. While it was clear to many, including ʻAbdu’l-Bahá, that missionary institutions like SPC were in a “losing fight” and the forces of liberalism were in the ascendant, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was unstinting in His support of religious education of a certain type, an education in “service to the cause of morality” and “animating [students] with the excellences and perfections of the religion of God.” As He had explained a year and a half before at Stanford:

Fifty years ago Bahá’u’lláh declared the necessity of peace among the nations and the reality of reconciliation between the religions of the world. He announced that the fundamental basis of all religion is one, that the essence of religion is human fellowship and that the differences in belief which exist are due to dogmatic interpretation and blind imitations which are at variance with the foundations established by the Prophets of God.25‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/819122974

For ʻAbdu’l-Bahá, religion was one, and it was indispensable to the success of any educational enterprise if it encouraged love and unity. However, as He repeatedly made clear, “if religious belief proves to be the cause of discord and dissension, its absence would be preferable.”26‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/819122974 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision for religious education, then, was unifying but also demanding; such education had to generate higher levels of unity than that previously attained.

Responding to the well-documented protests of those in the Muslim community, including many reformers, who thought the religious services would have a negative effect on the students, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá remarked, “I am sure the morals of the students will not be corrupted. They will be informed with the contents of the Old and New Testament. What harm is there in this? A church is house of prayer. Let them enter therein and worship God. What wrong is there in this?”27Redman, Visiting, 25. Indeed, He viewed such attendance as a potential benefit to all concerned:

I have no doubt that much good will be accomplished, and many misunderstandings will be removed, if the [Muslims] attend the Churches of the Christians with reverence in their hearts and sincerity in their souls, and likewise the Christians may go [to] Mohammedan Mosques and magnify the Creator of the Universe. Is it not revealed in the Holy Scriptures that ‘My House shall be called of all nations the House of Prayer? All the houses of different names, — Church, Mosque, Synagogue, Pagoda, Temple are no other than the House of Prayers. What is there in a name? Man must attach his heart to God and not to a building. He must love to hear the name of God, no matter from what lips…28Redman, Visiting, 25.

To be clear, His support was not out of sympathy with the college’s longstanding mission, however liberally construed, to convert students to Protestantism, but out of a conviction of the oneness of God and religion, stressing universality and commonality of worship. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s approach bore some commonalities with those of Muslim reformist thinkers and other liberals but differed in key respects. The well-known reformer Muhammad ‘Abduh, whom ‘Abdu’l-Bahá met with during His 1887 visit to Beirut, embraced the adoption of modern science for the benefit of Islamic societies; however, he advocated for the development of Muslim schools and criticized the effect on students of attending foreign ones, for it estranged them from their own culture and religion.29Scholz, “Foreign Education,” 95. The modernizer Rashid Rida also pointed to the “corrupting” force of such schools, though conceding that those who had had adequate religious instruction could attend them without any danger of losing faith. Even so, while supportive of the education the college provided, he disapproved of participation in “Christian” services.30Scholz, “Foreign Education,” 99, 187. And though liberal figures (such as Suleyman al-Bustani, Beirut’s parliamentary representative in Istanbul) voiced support for the idea that the younger generation could transcend racial and religious differences and worship together,31Scholz, “Foreign Education,” 188. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s comments explicitly and seriously included the idea of Christians themselves going to mosques to worship as well, a possibility that others would have found difficult to imagine. His was a voice for a kind of radical equality that challenged liberals at the college and reformists in the wider society alike.

During those years, liberals at the college like Bliss had been moving SPC in directions that were increasingly consonant with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s bold vision. Giving up on converting students to Protestantism as the college’s primary goal, Bliss identified the fostering of religious harmony as integral to the college’s mission. As he put it, the “equal treatment for men of all religions” produces “an atmosphere of good will and moral sympathy among men of the most divergent religious belief.”32Annual Report by the President to the Boards of Managers and Trustees, 1915-16, 6-7, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. In response to the 1909 crisis, Bliss had reminded his board of trustees:

We must put ourselves in the place of our non-Christian students,– our Moslems, our Tartars, our Jews, our Druses, our Bahais…We must not dishonor his sense of honor; and we must not feel that the work of the College has fulfilled the mission until these men and their fellow religionists who form a great majority of the Empire’s population are touched and molded by the College influence.33Annual Report, 1908-09, 16.

In 1922 Laurens Hickok Seelye, a member of the AUB faculty, published in The Journal of Religion an article entitled “An Experiment in Religious Association” in which he presented the college’s (now university’s) religious policy as a “radical step” for a “Christian institution.”34Laurens H. Seelye, “An Experiment in Religious Association,” The Journal of Religion 2, no. 3 (May 1922): 303-04. Howard Bliss, he wrote, had redefined the “faith of the missionary,” which was not to “urge upon others conformity, but a gracious invitation…to learn together of the progressing revelation of God.”35Seelye, “Experiment,” 303. Bliss “put into actual missionary achievement the belief of every scientific student of religious experience.”36Seelye, 303. Seelye highlighted as a concrete sign of Bliss’s success the number of Muslims and other non-Christians the college had attracted.37Seelye, 304. In 1920-1921, they, in fact, outnumbered the Christians by 511 to 490, with 382 Muslims, 66 Jews, 41 Druze, and 22 Bahá’ís.38Annual Report, 1920-21, 15.

“An Experiment in Religious Association”

In the 1910s, the college’s religious instruction and “influence” increasingly involved interfaith dialogue, in which the Bahá’í students actively participated. The college chapter of the Young Men’s Christian Association, or YMCA, attracted a diverse group of students eager to discuss religious subjects, according to Bayard Dodge, Bliss’s son-in-law and successor as college president. Dodge joined the faculty in 1913 and was also executive secretary of the YMCA chapter. In his 1914 annual report for the YMCA, he wrote:

This winter about fifteen men used to gather every Sunday morning to discuss the five different types of religion which they represented. They took a keen interest, but never were intolerant or even hot-headed, so that they showed what an easy matter it is to talk over differences and reforms, without any fear of unpleasant feeling.39Bayard Dodge, Report of the Beirut YMCA, 1913-14, 8, American University of Beirut/Library Archives.

It is evident that the “five different types of religion” included Bahá’ís, along with Christians, Muslims, Druze, and Jews. The Bahá’í students had already received the college’s unofficial consent to hold their own meetings on campus, though many at the college and in the missionary community opposed the practice. On Sunday afternoons, the members of the Society of the Bahá’í Students of Beirut would “gather under the trees in the university [SPC] or in their private rooms, chanting prayers and talking over matters of religious concern.”40Zeine, “Program.”

Dodge had written: “On Sunday morning I meet a group of Moslems and Bahá’ís, who discuss all sorts of religious questions in a most broadminded way and are intensely interesting.”41Bayard Dodge to Cleveland H. Dodge, December 1913, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. In one of Dodge’s earliest letters from the College, dated 26 November 1913, he singled out the Bahá’ís for their interest in such activities: “they try to take the best out of all religions.”42Bayard Dodge to “Bub,” 26 November 1913, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. While such interfaith activities were encouraged, they were seen to take place under the umbrella of the college’s Christianity. A very small number (12 out of 177) of YMCA members were not Christians, perhaps because as non-Christians, they could join only as associate members. By Dodge’s own admission, many other such students attended “most of the meetings, but feared to have the name ‘Christian’ in any way associated with them.”43Bayard Dodge, Report, 6. Despite the disinclination felt by many students toward being part of a Christian association, however, Dodge did not yet perceive any conflict with the fact that the YMCA was the only formal organization for these kinds of activities. Ottoman pressure ultimately succeeded in forcing the college to disband all student societies, including the YMCA, in May 1916.

During the war, the college’s religious regulations underwent dramatic changes. The subsequent, and in part consequent, upsurge in enrollment of Muslim students to the college who would now be exempt from mandatory religious exercises had caused deep anxiety in Bliss, Dodge, and others. West Hall, constructed in 1914 for student activities, became a refuge for the students from the increasingly harsh wartime conditions outside the college walls. It was also a venue for the college’s experiment in religious association to break new ground. The closing of the YMCA, along with the other student societies, in 1916; the continuation of the informal interfaith discussion groups started before the war during which time “the association in worship became freer than ever”44Seelye, “Experiment,” 305. ; and the much-vaunted sense of solidarity that the war seemed to intensify – all of these had paved the way for the formal creation of a new organization, a “Brotherhood,” envisioned by Bliss in a speech at the building’s opening. In a sermon given on 8 February 1914 titled “God’s Plan for West Hall,” Bliss had identified as the new building’s “supreme purpose the awakening in the men who make use of West Hall of the spirit of service, of ‘the struggle for the life of others’”; instrumental for such a purpose, Bliss proposed, was “a West Hall Brotherhood.”45Al-Kulliyah, March 1914, No. 5, 136.

It was not until 1920, however, that the West Hall Brotherhood properly got on its feet, when Laurens Seelye arrived to become the director of West Hall. Two years later, in his aforementioned article “An Experiment in Religious Association,” he explained the emergence of the West Hall Brotherhood. Deriding the patronizing policy of associate membership for non-Christians in the YMCA, Seelye discussed the delicate balance he and others tried to achieve in making the Brotherhood “non-Christian” even while the University remained a “Christian missionary institution.”46Seelye, “Experiment,” 305-06. Important to membership in the Brotherhood was the belief that, as stated in its Preamble, “a thoughtful, sincere man, whether Moslem, Bahai, Jew or Christian can join this Brotherhood without feeling that he has compromised his standing in relation to his own religion.”47Seelye, “Experiment,” 307. A few Bahá’ís would have been among the twelve non-Christian members of the YMCA in 1913-14, as these twelve were “very equally divided amongst men of the different sects.”48Bayard Dodge, Report, 6.Yet, as with the other non-Christians, joining the Brotherhood would have been a far more acceptable alternative for the Bahá’ís. The Brotherhood’s “Pledge” did not name any single religion but only “this united movement for righteousness and human brotherhood.”49Seelye, “Experiment,” 308. In 1921, Dr. Philip Hitti, the renowned Princeton scholar who was then a young faculty member at his alma mater AUB, wrote that the Brotherhood’s “watchword shall be ‘unity through diversity.’”50Al-Kulliyah, Nov. 1921, No. 1, 4.

The Bahá’í Students’ Contribution

The Bahá’í students’ participation in such intercommunal spaces was complemented by similar experiences they had gained within their own community, both in Beirut as well as in Haifa and Egypt. Part of the reason for Bliss’s 1914 visit was to arrange for the April visits of the Bahá’í students in Beirut, 27 of whom would make the trip (out of around 30-35 total students)51Redman, Visiting, 23. For a broader overview of the Bahá’í students in Beirut, including detailed statistical information, see Richard Hollinger, “An Iranian Enclave in Beirut: Baha’i Students at the American University of Beirut, 1906-1948,” in Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years, ed. H.E. Chehabi (Oxford: Centre for Lebanese Studies in association with I.B. Taurus, 2006) 96-119.; 20 students, in two groups, visited ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in Egypt in September 1913.52Ahang Rabbani, ed., The Master in Egypt: A Compilation, Studies in the Babi and Baha’i Religions, Vol. 26 (Los Angeles: Kalimat Press, 2021) 240, 285-86. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá met with these students often during their visits (sometimes twice a day), encouraging them in their studies and asking them if their teachers “took pains to instruct the students.”53Rabbani, Master, 248. He urged them to “strive always to be at the head of [their] classes through hard study and true merit” and to “entertain high ideals and stimulate [their] intellectual and constructive forces.” 54Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98. He prioritized the study of agriculture and directly encouraged students to study medicine, in addition to subjects that would lead to careers in commerce and industry. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá also encouraged postgraduate studies, at Stanford, for example.55Rabbani, Master, 305.

Beyond their academic pursuits, however, the Bahá’í students received an education in the kind of united world ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was so interested in cultivating. He urged them to “strive to beautify the moral aspect of [their] lives” through the “divine ideals [of] humility, submissiveness, annihilation of self, perfect evanescence, charity, and loving kindness.” They must, He added, “Love and serve mankind just for the sake of God and not for anything else. The foundation of [their] love toward humanity must be spiritual faith and divine assurance.”56Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98. Not only did ʻAbdu’l-Bahá spend time with them and address them on various subjects, but the students also read copies of His talks from His 1912 trip to America.

The effect of these visits on the students was immense. As Badi Bushrui, who was among the students that visited ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in both Egypt and Haifa, later reflected, “Here is an interesting scene: the Hindu, the Zoroastrian, the Jew, the Moslem, and the atheist start singing songs of joy, praising BAHA’O’LLAH that, through His Grace, they were enabled to meet on the common-ground of Unity…”57Redman, Visiting, 24. Bushrui here is identifying people by their source communities, emphasizing the unifying effect of their attraction to the Bahá’í teachings. Indeed, the Bahá’í students were themselves a diverse group; though most were from Persia, they came from Muslim, Jewish, and Zoroastrian backgrounds. In addition, on all their visits, the students interacted with Bahá’ís from Western countries, Americans especially.

The Bahá’í students’ experience visiting ʻAbdu’l-Bahá reinforced their efforts to contribute to the life of the college, and they actively sought out spaces in which they could put into practice their spiritual education. It was through this lens that Bahá’í students participated in religious services at SPC. They were not simply tolerating the Protestant services but viewing them in this far more unifying spirit. They also took advantage of opportunities to participate in the intercommunal spaces that opened up when the services became optional for non-Christians.

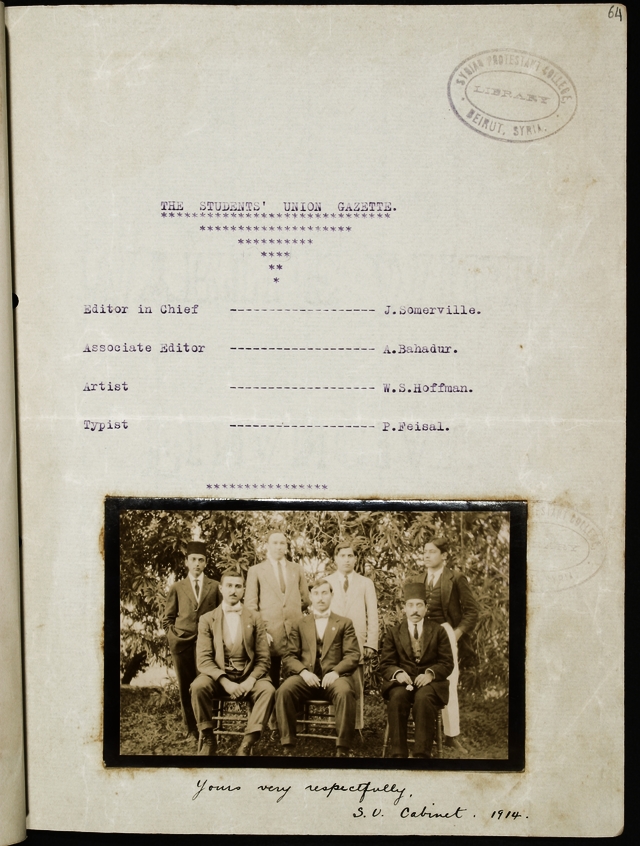

But the main venue for the Bahá’í students’ contribution to the college was the Students’ Union, which put on plays and organized a Social Service Institute and a Research Club, besides holding meetings. The most important ones were its weekly Saturday night meetings at which various topics were discussed and debated and the business meetings at which “parliamentary rules [were] observed and practiced.”58Al-Kulliyah, July 1910, No. 6, 229. There were also speaking contest meetings, election meetings, and reception meetings. The twin aims of the Union were “to cultivate and develop public speaking and parliamentary discipline in its members.”59Students’ Union Gazette, 1913, 65, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. Published every two months was the Students’ Union Gazette, the student magazine that had the longest run during this period.60Anderson, American University of Beirut, 22. The Union operated “exclusively” in English61Students’ Union Gazette, 1913, 65., and indeed in his history of AUB, Bayard Dodge refers to the Union as an “English society.”62Bayard Dodge, The American University of Beirut: A Brief History of the University and the Lands Which It Serves (Beirut: Khayat, 1958), 33. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá encouraged the Bahá’í students to perfect their English and to give talks in the language, something they practiced while visiting Him in Egypt and Haifa.63Rabbani, Master, 304.

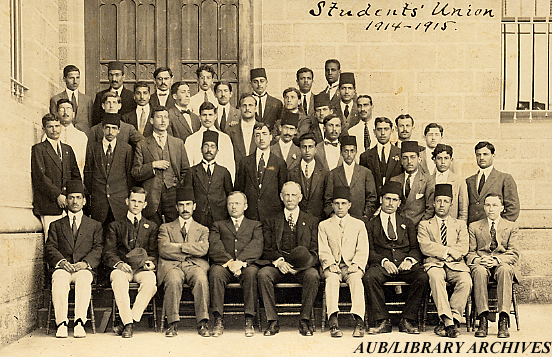

By 1912 at least, this group was playing an active role in campus life. From the time the Bahá’í students began to form a recognizable group on campus, they became dynamic members of the Union, being elected to the Union’s Cabinet, contributing to the Gazette, participating in and winning prizes in debate contests, and also proposing subjects for debate at the Saturday night meetings. From 1912 until 1916, when all student societies were closed down, Bahá’í students were almost continuously represented in the Students’ Union Cabinet, elections for which were held twice a year. Twice Bahá’í students were elected its president; twice its vice president; at least once its secretary; once its associate secretary; twice the editor of the Students’ Union Gazette; once the president of its Scientific Department; and several times as members-at-large.

Their contributions to the Union – through the topics they suggested for debate, the talks they gave, and the articles they wrote – reveal the focus of their interests: promoting greater unity among the diverse groups of students in the service of universal peace, all the while including a dynamic role for religion. In April 1914, one student proposed that a “universal religion is possible” while another, ‘Abdu’l-Husayn Isfahani, put forth that “Universal Reformation in all the different phases of life can never be effected except through religion”64Students’ Union Gazette, 1914, 60 and Al-Kulliyah, April 1914, No. 6, 192.; Isfahani in a January 1913 speaking contest on “Is reputation an index of true greatness?” had elaborated on this conception of a “universal religion,” basing his argument on the transcendent universality of the founders of major religions – their “creative and inspiring power.”65Students’ Union Gazette, 1913, 35. Jesus Christ, Muhammad, and Buddha, he argued, through their “brilliant commanding genius” accomplished what they did in the face of societal opposition. Thus, their reputations do indicate true greatness. Isfahani also proposed that month that “racial differences do not exist.”66Al-Kulliyah, April 1914, No. 6, 192.

The Bahá’ís continued their involvement with the Students’ Union in the following decades. In 1929, for example, Hasan Balyuzi gave a talk for a speaking contest on the “religion of the future,” which would be characterized by “plasticity, absence of hypocrisy, and spirit of universal brotherhood.”67Al-Kulliyyah, June 1929, No. 8, 238.

At a time when issues of war and peace were very much of the moment, the Bahá’í students sought to promote universal peace. In the years immediately before World War I, Bahá’í students proposed antiwar debate topics, such as “war must inevitably stop,” and wrote articles such as “Towards International Peace.” One such student, Aflatun Mirza, proposed that “a universal language is essential to the progress of the world.”68Al-Kulliyyah, May 1912, No. 7, 227. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in His talks in America and Europe had supported the establishing of a secondary, auxiliary language to facilitate greater unity and lead to peace.69Balyuzi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 330. In the 1920s, in fact, many Bahá’ís became active members of the worldwide Esperanto movement. One Bahá’í student, Zeine N. Zeine, was an enthusiastic promoter of the language on campus, giving talks on it, including, on at least one occasion, a short one in Esperanto itself.70Al-Kulliyyah, February 1929, No. 1, 99.

However, even more revealing of the way the Bahá’í students understood their contribution to this discourse was a speech given by Zeine in 1929, a talk that won a prestigious speaking contest. In “Mental Disarmament,” he claimed that such disarmament was more “necessary to peace and happiness of the world than the disarmament of the sword.” Attitudes, he continued, such as “intolerance, ignorance, hatred, prejudice” and so on “play more havoc than the cannon, and bring about strife and war.”71Al-Kulliyyah, April 1929, No. 6, 153. (Appropriately, Zeine, upon his graduation that year, was hired as assistant director of West Hall and an instructor of Sociology.) In a similar vein, the president of the Students’ Union, not a Bahá’í, at the Brotherhood’s year-opening reception in October 1926, remarked, “the Druze, the Moslem, the Jew, the Bahai, the Christian all unite together to oppose others of the same religion for the welfare of the Union.”72Students’ Union Gazette, 1926, 7-8. Back in June 1914, Badi Bushrui, who was the outgoing president of the Union, offered a succinct summary of the way Bahá’ís sought to contribute not only in their words but also in their deeds:

Let the Union, as often suggested by President Bliss, stand for universal peace and the oneness of the world of humanity. I am glad that the spirit which the college tries to infuse into her students is finding expression in the life of the Union. Racial and religious differences play no part there. The President for the first term this year was a Christian, the last President was a Bahai and the new President is a Moslem. I believe this is the biggest stride the Union has taken to be able to choose the best man without regard to religious or racial affinity.73Al-Kulliyyah, June 1914, No. 8, 26.

Furthermore, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s guidance addressed the practical outcomes of their education. In Egypt in 1913, for example, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá told the students that it was “his hope that they would make extraordinary progress along spiritual lines as well as in science and art; so that each one might become a brilliant lamp in the world of modern civilization, and upon their return to Persia that country might profit from their acquired knowledge and experience.”74Rabbani, Master, 241. Out of 24 Master’s theses written before 1918, five were written by Bahá’í students.75Hollinger, Distant Relations, 111. Two theses, both written in 1918, exemplify this focus on serving the best interests of their nation. “Social Evils or Hindrances to Persia’s Progress” and “Persia in Transformation,” both written by Bahá’í students, identified elements of Persia’s religious, social, and political life needing attention and articulated a progressive vision for the country, assigning prominent places to education and the rights of women.76Azizullah Khan S. Bahadur, “Social Evils or Hindrances to Persia’s Progress” (MA thesis, American University of Beirut, 1917); Abdul-Husayn Bakir, “Persia in Transformation” (MA thesis, American University of Beirut, 1918).

In a letter to his father dated 22 June 1914, Dodge commented on this mission of the Bahá’í students. “Most of these students travel to the College from three to four weeks away,” he related, and “speak in a most serious way of getting an education here and then returning to help their unfortunate land.”77Bayard Dodge to Cleveland H. Dodge, 22 June 1914, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. Dodge’s initial encounters with the Bahá’í students in 1913 led him to state that “they uphold all sorts of good reform movements.”78Bayard Dodge to “Bub,” 26 November 1913, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives.

The Bahá’í students also contributed to the college-wide efforts to render service to the local community, efforts which greatly accelerated during the war, including medical relief activities, among others. Not long after the war broke out, most of the Bahá’ís in Haifa and ‘Akká, including Badi Bushrui and another recent SPC graduate Habiballah Khudabakhsh, later known as Dr. Mu’ayyad, were received as guests in the Druze/Christian village of Abu-Sinan.79Balyuzi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 411. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s warm relationship with the village leaders had made this arrangement possible. In an article titled “A New Experience,” published in a fall 1915 number of the Students’ Union Gazette, Bushrui relates how Dr. Mu’ayyad started a medical clinic in the village, performing many operations and treating a variety of conditions over a period of eight months. 80Bayard Dodge, “Education As a Source of Good Will” in The Bahá’í World (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1933) 4: 370. Bushrui and an American Bahá’í woman, Lua Getsinger, acted as nurses and assistants; Bushrui also taught some of the children. Such an experience of social service would have resonated deeply with the emerging ethos of the college, to be sure.