The Bahá’í writings describe the modern period as an age of transition toward a future world civilization that manifests the oneness and essential diversity of humankind. The “world’s equilibrium,” Bahá’u’lláh writes, has been “upset” by the “vibrating influence” of “this most great, this new World Order.” The Universal House of Justice further elaborates upon Bahá’u’lláh’s remarks by likening these disruptive transformations to the period of adolescence: “Humanity, it is the firm conviction of every follower of Bahá’u’lláh, is approaching today the crowning stage in a millennia-long process which has brought it from its collective infancy to the threshold of maturity—a stage that will witness the unification of the human race. Not unlike the individual who passes through the unsettled yet promising period of adolescence, during which latent powers and capacities come to light, humankind as a whole is in the midst of an unprecedented transition. Behind so much of the turbulence and commotion of contemporary life are the fits and starts of a humanity struggling to come of age. Widely accepted practices and conventions, cherished attitudes and habits, are one by one being rendered obsolete, as the imperatives of maturity begin to assert themselves.”1Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, www.bahai.org/r/581649978; Universal House of Justice, “A Letter to the Bahá’ís of Iran, Dated 2 March, 2013,” www.bahai.org/r/394327546. This essay explores the idea of modernity as an age of transition as presented in the Bahá’í writings.2Other sources develop resonant accounts of modernity as an age of transition. See, for example, such mid-twentieth century works as: Lewis Mumford, The Transformation of Man (New York: Harper & Row, 1956); Karl Jaspers, The Origin and Goal of History, trans. Michael Bullock (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1953); Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Human Phenomenon, ed. Sarah Appleton-Weber (Eastbourne, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 1999). Or, more contemporaneously: Robert Wright, Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny, n.d.; Prasenjit Duara, The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian Traditions and a Sustainable Future (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Joseph Chan, Confucian Perfectionism: A Political Philosophy for Modern Times (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

The origins of the modern age of transition

The modern age of transition begins as a movement out of the medieval order of civilization, some prominent expressions of which include the Song Dynasty of imperial China (960-1279 CE), the Hindu-Islamicate society of Mughal India (1526-1857 CE), the Mali Empire of West Africa (1235-1670 CE), and orthodox-Christian Byzantium (286-1453 CE). Each of these medieval societies relied upon a material substrate of village-based agrarian activity. These agrarian villages were, in turn, ruled by a cadre of urban elites whose authority was thought to hierarchically descend from the divinely sanctioned powers of a single emperor or king. Both social layers were, in turn, embedded in a common religious-metaphysical system, among which those associated with Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Neo-Confucianism were concurrently preeminent. And although by around 1250 CE, certain Old World elites had established a meaningful web of Afro-Eurasian interconnections, each medieval society still largely continued to consider itself civilizationally autonomous.3For useful descriptions of the medieval order of civilization see: Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-135 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 103–117; Rethinking World History: Essays on Europe, Islam, and World History, ed. Edmund III Burke (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 44–71; Mumford, The Transformation of Man, 81–94.

Precisely how and when the medieval order began to decline is a matter of scholarly debate. What is clear, however, is that the upheavals of the “long nineteenth century”—from roughly 1770 to 1920—inaugurated the modern age of transition by firmly uprooting the foundations of medieval civilization. The advent of industrial manufacturing undermined the agrarian, village-based substrate of medieval life by unleashing the explosive powers of fossil fuels, mechanical technology, and megapolitan urbanization. Populist revolutions in the United States (1765-1791), France (1789-1799), and Haiti (1791-1804) stimulated novel vectors of political change that would, by the middle of the twentieth century, help topple most of the world’s great monarchical empires. The spreading influence of secular and materialistic ideologies disrupted the taken-for-granted authority of long-established ecclesiastical institutions and religious creeds. And a succession of pathbreaking transportation and communication technologies, including the steamboat (1803), the locomotive (1804), electric telegraphy (1844), the petrol automobile (1886), broadcast radio (1896), and the airplane (1903), overwhelmed medieval notions of civilizational autonomy by dramatically interlinking the far-flung regions of the earth. One by one, then, each of the established pillars of medieval civilization were decisively displaced during the long nineteenth century.4Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century, trans. Patrick Camiller (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 47.

An era of ideological frustration

The upheavals of the long nineteenth century aroused a gusty season of intellectual commotion and ferment. How, every attentive mind began to wonder, should a just, peaceful, and prosperous society be structured if not by the age-old medieval pillars of village-based agrarianism, monarchical empire, and ecclesiastical religion? Given the outsized influence that, at the time, European and North American peoples enjoyed, many intellectuals attempted to answer this question by presenting certain impressive features of modernizing Western societies—their pursuit of rational self-determination; their relentless strivings for scientific and technological progress; their expanding commitments to democratic politics and the self-correcting dynamism of free markets; their burgeoning schemes of political-economic equalization; or even their nationalistic enthusiasms—as the crucial foundations of a new, modern order of civilization that all peoples must eventually embrace.

The Western-centric inquiries of nineteenth-century thinkers yielded a constellation of influential ideologies—including liberalism; capitalism; socialism; nationalism; anarchism; secular humanism; scientific materialism; organicism; techno-utopianism; and enlightened despotism—that illuminated certain real features of the modern age of transition. Yet these ideologies also each employed so many problematically one-sided and parochially self-centered assumptions that subsequent efforts to enact their claims ended up lurching back and forth between moments of encouraging progress and of demoralizing frustration. One thinks, for example, of how the efforts of revolutionary France to politically enact the ideals of liberty, equality, and solidarity were swiftly followed by the authoritarian repressions of the Reign of Terror and the Napoleonic regime. Or one could also mention how endeavors to demonstrate the universal validity of modern science, advanced by such thinkers as Denis Diderot (1713-1784) and August Comte (1798-1857), helped to stimulate a encouraged new constellation of obscuring materialistic orthodoxies.

Noting these difficulties, long-nineteenth-century thinkers strove to remedy the many defects that plagued their cherished modern ideologies in at least three broad ways. First, there were those who, like J.W.F. Goethe (1749-1832), John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), Karl Marx (1818-1883), and Walt Whitman (1819-1892), claimed that humanity could only continue proceeding down the path of modern progress by more consistently or radically embracing the ideals of the Enlightenment, particularly those of freedom, equality, and rationality. Second, many others advanced the countervailing claim that redressing the ideological failings of Western modernity required revitalizing one or another of humanity’s great pre-modern traditions; consider, for example, of the efforts of Friderich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Søren Kierkegaard (1817-1855), and the architects of the Meiji Restoration, respectively, to re-engage the ethos of Homeric polytheism, of early Christianity, and of Japanese Shintoism. And third, one encounters an expanding cohort of voices who, in the manner of a Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) or Max Stirner (1806-1856), suggested that a more ideal society could emerge only after the West’s moral-ideological pretensions had been firmly subverted and exposed. The intellectual landscape of the long nineteenth century was, therefore, cross-pressured by efforts to show how the crucial defects of Western modernity could be resolved by more comprehensively embracing Enlightenment ideals, or by revitalizing some premodern ethico-spiritual tradition, or by critically vitiating the dark side of modern Western civilization.

Much has obviously taken place since the close of the long nineteenth century, including such world-shaking events as the Great Depression; the Second World War; the nuclear proliferations of the Cold War; decolonization and the third wave of nation-state formation; the “Big Push” of international development; the formation of the United Nations; the establishment of the international human rights regime; the rising global clout of East and South Asian societies; the digital revolution; and the accelerating trajectory of anthropocentric climate change. And yet, dominant intellectual discourses—especially in the West—continue to swirl within the same limited horizon of ideological possibilities that crystallized between 1770 and 1920. Indeed, despite the impressive advancements in knowledge that have taken place during the century, many among our most prominent thinkers continue to assume that, if contemporary humanity is ever to address its mounting civilizational woes, it must do so either by re-committing itself to the ideals of the Enlightenment, renewing its engagement with some older and ostensibly superior tradition, or disruptively deconstructing the oppressive and disingenuous foundations of modern Western civilization.

The analogy of collective adolescence

The age of transition thesis discloses a new horizon of interpretive possibilities. It recasts the tumultuous vectors of modern thought and social change as the initial expressions of a still-unfolding process of global-civilizational transformation that can be likened to the collective adolescence of humankind. “The long ages of infancy and childhood through which the human race had to pass, have receded into the background,” proclaims Shoghi Effendi, who served as the administrative head of the Bahá’í Faith from 1921 to 1957, in a letter written several years before the outbreak of the Second World War. “Humanity is now experiencing the commotions invariably associated with the most turbulent stage of its evolution, the stage of adolescence, when the impetuosity of youth and its vehemence reach their climax, and must gradually be superseded by the calmness, the wisdom, and the maturity that characterize the stage of manhood. Then will the human race reach that stature of ripeness which will enable it to acquire all the powers and capacities upon which its ultimate development must depend.” Or again, as the Universal House of Justice explains, “the human race, as a distinct, organic unit, has passed through evolutionary stages analogous to the stages of infancy and childhood in the lives of its individual members, and is now in the culminating period of its turbulent adolescence approaching its long-awaited coming of age.”5Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, www.bahai.org/r/166959448; Universal House of Justice, The Promise of World Peace, www.bahai.org/r/562133059.

This image warrants careful consideration. For individuals, the period of adolescence is marked by the rapid development of adult-like capabilities. Yet a mature framework within which to orient these new powers is initially lacking. The young person must struggle to clarify the concepts, values, and identities upon which they will rely as they approach the threshold of adulthood. This is an immensely challenging task, and it is made even more difficult by the young person’s competing attachments to the well-known norms of childhood, burgeoning enamorments with their own mental and physical capabilities, and deepening uncertainties about the merits of different models of adult living. Indeed, it is precisely from the resultant sense of disorientation that arise the patterns of “turbulence,” “impetuosity,” and “vehemence” that are so consistently associated with the period of human adolescence.

When applied to the modern age of transition, the analogy of adolescence recasts the proliferating welter of modern ideologies, not as the expression of some unsurpassable state of social, political, and intellectual maturity, but rather as the chaotic yet promising outgrowth of humanity’s burgeoning abilities to envision a new era of a globally-integrated civilization. The analogy additionally encourages a long-term vision of social change that can enable successive generations to continue laboring to erect an organically transfigured world society. In this regard, one might consider the difference between the young person who, because they see themselves living only for today, dissipates their energies in the pursuit of fleeting pleasures and enthusiasms, and another, who, by remaining more acutely aware of the looming imperatives of adulthood, conscientiously devotes themselves to undertakings that prepare them for what lies ahead.

The effort to analogically reconfigure one’s narrative of history, moreover, helps clarify the crucial role that other analogies already play in shaping thought about modern history. Indeed, the very notion of enlightenment constitutes one such influential analogy, suggesting the ideals of banished illusion and of rationally clarified perception that have profoundly influenced the trajectory of modern Western culture and history. And one can also readily identify several other images—based, for example, on the model of atomic interaction, or on the naturally selective pressures of jungle life, or even on the operations of industrial factories and mechanical clocks—that continue to orient prevalent ideas about specific features of modern social existence. Consequently, instead of aspiring to supplant the ostensibly objective and neutral narratives of modernity that contemporary intellectuals employ with an unduly imagistic one, the age of transition thesis actually endeavors to transform the existing analogical contents of modern historical imagination.

Toward a new horizon of research and intellectual activity

If the age of transition thesis is to ever become widely influential, much more will be required than simply enumerating its various conceptual and interpretive merits. The idea must additionally be incorporated into a new and robustly advancing pattern of research and intellectual activity. To shed further light on how an expanding constellation of individuals, communities, and institutions might practically address this far-reaching challenge and opportunity, the author draws on his experience with a nascent research organization, the Center on Modernity in Transition. Before exploring this particular body of experience, however, it may be useful to offer some additional insight into the intellectual transformation that is being considered by briefly exploring the history of the modern research university.

The institution of the modern research university arose in Germany during the early nineteenth century, and is widely recognized as beginning with the founding of the University of Berlin in 1809. Unlike its medieval predecessors, such as the universities of Paris or Oxford, which functioned as scholastic guilds that pursued the ideal of orthodox intellectual integration, the modern research university was meant to advance intellectual endeavors that grew out of the novel idea of modernity as a dawning age of rational and scientific enlightenment. One major strategy that these universities employed was to situate the proliferating research activities that Enlightenment thinkers pursued within a handful of specialized disciplines and fields. As explained by the well-known Enlightenment philosopher, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the modern research university was to lead humanity further into the dawning Age of Enlightenment by managing “the entire content of learning … like a factory, so to speak—by a division of labor, so that for every branch of the sciences there would be a public teacher or professor appointed as its trustee, and all of these together would form a kind of learned community called a university.”6Immanuel Kant, “The Conflict of the Faculties (1798),” in Religion and Rational Theology, trans. Mary J. Gregor and Robert Anchor, The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 247. The disciplinary order of knowledge that now orients our world thus arose within the efforts of modern research universities to systematically embed the idea of modernity as a dawning age of enlightenment in a new pattern of research and intellectual activity. By extension, it would seem reasonable to expect the mature development of the idea of modernity as an age of transition to entail at least an equally weighty and institutionally complex transformation in the intellectual life of humankind.

The writings of philosopher Imre Lakatos (1922-1974) further illuminate the actual process by which such an intellectual transformation might proceed. Specifically, Lakatos claims that every serious research endeavor relies upon a “hard core” of conceptual presuppositions that are never directly tested, but rather used to support an evolving “protective belt” of rigorously evaluated theories, propositions, and methodologies. For Lakatos, the main distinction between a scientific program of research and a non-scientific one lies not in the extent to which they respectively employ empirically unverified assumptions—both of them inescapably do—but rather in the degree to which their conceptual presuppositions sustain a progressively advancing system of secondary theories, propositions, and methodologies. Consequently, instead of endeavoring to conclusively demonstrate the veracity of the age of transition thesis before proceeding any further down the path of inquiry that the idea suggests, Lakatos’s arguments suggest that one must simply get started trying to use the idea to ground a new and robustly advancing program of research and intellectual activity.7Imre Lakatos, The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Volume 1: Philosophical Papers (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1980).

In this regard, it may be useful to mention the nascent efforts of one research organization. the Center on Modernity in Transition (COMIT), with which the author has, since its establishment in early 2020, been energetically engaged. As the organization explains in a recent report, “the Center on Modernity in Transition aspires to contribute to the intellectual life of the emerging world civilization envisioned by Bahá’u’lláh. We begin from the premise that if one interrogates deeply enough the sources of humanity’s pressing challenges, one arrives ultimately at a network of concepts and assumptions that undergird the current order, and that shape the ways in which social reality is read, understood, and constructed. The broad aim of COMIT is thus to rigorously examine the intellectual foundations of modern society and to contribute, however gradually, to their transformation. COMIT pursues this goal by working to establish a new and dynamic research program animated by the idea of modernity as an age of transition toward a new world civilization—one characterized by unprecedented levels of unity, justice, peace, and material and spiritual prosperity.”

In support of its long-term, research-program-building agenda, the Center pursues two interrelated areas of activity. COMIT aspires to advance novel and distinctive lines of research that are rooted in the idea of modernity as an age of transition, as well as in the various fundamental concepts that underpin the idea. At the same time, however, the organization strives to contribute to a growing number of academic discourses and fields that, in one way or another, help to illuminate various facets of the modern age of transition. Neither endeavor can, the Center maintains, be effectively pursued in isolation from the other. For without consistently engaging the best knowledge and methodologies that humanity has produced, COMIT’s attempts to build a new research program would struggle to significantly improve upon the patterns of intellectual activity that operate within the world’s leading research universities. Inversely, however, if the Centre focuses only on advancing the kinds of research that existing academic institutions pursue, it would soon find itself unable to meaningfully contribute to the establishment of a new and highly distinctive program of research and intellectual activity. COMIT thus aspires to advance both endeavors in a complementary and coherent manner.

A series of initial developments suggests the fecundity of COMIT’s approach. Relevant examples include the establishment of fruitful collaborations with academic bodies at Duke University, New York University, and Columbia University; the successful execution of a number of online speaker series—for example, The Liberal Imaginary and Beyond and Identity and Belonging in a Global Age—featuring a line-up of highly distinguished thinkers and practitioners, including Charles Taylor, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Barbara Fields, Cornel West, Seyla Benhabib, and Craig Calhoun; the development of a maturing web presence, particularly the organization’s webpage, comitresearch.org, and its YouTube channel, where video recordings of its events have been widely viewed; the raising of an initial tranche of funds to support the organization’s expanding research activities and the hiring of personnel; the establishment of several dynamic, distinctive, and externally well-received research projects; and the cultivation of an expanding network of committed thought partners and research collaborators. Although the organization remains acutely aware of the many challenges it must face as its efforts continue to gain in complexity and scope, it continues to derive sustenance and hope from the demonstrated abilities of the age of transition thesis to invite the enthusiastic participation of scholars situated within a wide variety of disciplinary, intellectual, and ethico-spiritual traditions.

What this article suggests is that, today, there is a unique opportunity for motivated researchers to begin rigorously embedding the distinctive vision of modernity as an age of transition, such as it is presented in the Bahá’í writings, into new and far-reaching patterns of research and intellectual activity. The example of the Center on Modernity in Transition provides some insight into the kinds of evolving research activities that might help to tangibly advance the envisioned intellectual transformation. At present, however, the simple fact remains that we can have little real knowledge of the precise content or shape of this future intellectual efflorescence. It is precisely for this reason that the Bahá’í writings consistently encourage us to regard the welter of tumultuous forces that characterize the modern age of transition through the lens of the organic metaphor. “It is,” as ‘Abdu’l-Baha writes, “even as the seed: The tree exists within it but is hidden and concealed; when the seed grows and develops, the tree appears in its fullness.”8’Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions: www.bahai.org/r/771160088. The immediately pressing task before us is for an expanding constellation of individuals, communities, and institutions to begin boldly and systematically pursuing the myriad opportunities for serious intellectual transformation and growth that can be discerned within the immediate contexts of their lives and social milieus.

The world’s great faiths have animated civilizations throughout history. Each affirms the existence of an all-loving God and opens the doors of understanding to the spiritual dimension of life. Each cultivates the love of God and of humanity in the human heart and seeks to bring out the noblest qualities and aspirations of the human being. Each has beckoned humankind to higher forms of civilization.

Over the thousands of years of humanity’s collective infancy and adolescence, the systems of shared belief brought by the world’s great religions have enabled people to unite and create bonds of trust and cooperation at ever-higher levels of social organization―from the family, to the tribe, to the city-state and nation. As the human race moves toward a global civilization, this power of religion to promote cooperation and propel cultural evolution can perhaps be better understood today than ever before. It is an insight that is increasingly being recognized and is affirmed in the work of evolutionary psychologists and cultural anthropologists.

The teachings of the Founders of the world’s religions have inspired breathtaking achievements in literature, architecture, art, and music. They have fostered the promotion of reason, science, and education. Their moral principles have been translated into universal codes of law, regulating and elevating human relationships. These uniquely endowed individuals are referred to as Manifestations of God

in the Bahá’í writings, and include (among others) Krishna, Moses, Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus Christ, Muhammad, the Báb, and Bahá’u’lláh. History provides countless examples of how these Figures have awakened in whole populations capacities to love, to forgive, to create, to dare greatly, to overcome prejudice, to sacrifice for the common good, and to discipline the impulses of humanity’s baser instincts. These achievements can be recognized as the common spiritual heritage of the human race.

Today, humanity faces the limits of a social order inadequate to meet the compelling challenges of a world that has virtually shrunk to the level of a neighborhood. On this small planet, sovereign nations find themselves caught between cooperation and competition. The well-being of humanity and of the environment are too often compromised for national self-interest. Propelled by competing ideologies, divided by various constructs of us

versus them,

the people of the world are plunged into one crisis after another—brought on by war, terrorism, prejudice, oppression, economic disparity, and environmental upheaval, among other causes.

Bahá’u’lláh—as the latest in the series of divinely inspired moral educators Who have guided humanity from age to age—has proclaimed that humanity is now approaching its long-awaited stage of maturity: unity at the global level of social organization. He provides a vision of the oneness of humanity, a moral framework, and teachings that, founded on the harmony of science and religion, directly address today’s problems. He points the way to the next stage of human social evolution. He offers to the peoples of the world a unifying story consistent with our scientific understanding of reality. He calls on us to recognize our common humanity, to see ourselves as members of one family, to end estrangement and prejudice, and to come together. By doing so, all peoples and every social group can be protagonists in shaping their own future and, ultimately, a just and peaceful global civilization.

One humanity, one unfolding faith

We live in a time of rapid, often unsettling change. People today survey the transformations underway in the world with mixed feelings of anticipation and dread, of hope and anxiety. In the societal, economic, and political realms, essential questions about our identity and the nature of the relationships that bind us together are being raised to a degree not seen in decades.

Progress in science and technology represents hope for addressing many of the challenges that are emerging, but such progress is itself a powerful force of disruption, changing the ways we make choices, learn, organize, work, and play, and raising moral questions that have not been encountered before. Some of the most formidable problems facing humanity—those dealing with the human condition and requiring moral and ethical decisions—cannot be solved through science and technology alone, however critical their contributions.

The teachings of Bahá’u’lláh help us understand the transformations underway. At the heart of His message are two core ideas. First is the incontrovertible truth that humanity is one, a truth that embodies the very spirit of the age, for without it, it is impossible to build a truly just and peaceful world. Second is the understanding that humanity’s great faiths have come from one common Source and are expressions of one unfolding religion.

In His writings, Bahá’u’lláh raised a call to the leaders of nations, to religious figures, and to the generality of humankind to give due importance to the place of religion in human advancement. All of the Founders of the world’s great religions, He explained, proclaim the same faith. He described religion as the chief instrument for the establishment of order in the world and of tranquility amongst its peoples

and referred to it as a radiant light and an impregnable stronghold for the protection and welfare of the peoples of the world.

In another of His Tablets, He states that the purpose of religion is to safeguard the interests and promote the unity of the human race, and to foster the spirit of love and fellowship amongst men.

The religion of God and His divine law,

He further explains, are the most potent instruments and the surest of all means for the dawning of the light of unity amongst men. The progress of the world, the development of nations, the tranquility of peoples, and the peace of all who dwell on earth are among the principles and ordinances of God. Religion bestoweth upon man the most precious of all gifts, offereth the cup of prosperity, imparteth eternal life, and showereth imperishable benefits upon mankind.

The decline of religion

Bahá’u’lláh was also deeply concerned about the corruption and abuse of religion that had come to characterize human societies around the planet. He warned of the inevitable decline of religion’s influence in the spheres of decision making and on the human heart. This decline, He explained, sets in when the noble and pure teachings of the moral luminaries who founded the world’s great religions are corrupted by selfish human ideas, superstition, and the worldly quest for power. Should the lamp of religion be obscured,

explained Bahá’u’lláh, chaos and confusion will ensue, and the lights of fairness and justice, of tranquility and peace cease to shine.

From the perspective of the Bahá’í teachings, the abuses carried out in the name of religion and the various forms of prejudice, superstition, dogma, exclusivity, and irrationality that have become entrenched in religious thought and practice prevent religion from bringing to bear the healing influence and society-building power it possesses.

Beyond these manifestations of the corruption of religion are the acts of terror and violence heinously carried out in, of all things, the name of God. Such acts have left a grotesque scar on the consciousness of humanity and distorted the concept of religion in the minds of countless people, turning many away from it altogether.

The spiritual and moral void resulting from the decline of religion has not only given rise to virulent forms of religious fanaticism, but has also allowed for a materialistic conception of life to become the world’s dominant paradigm.

Religion’s place as an authority and a guiding light both in the public sphere and in the private lives of individuals has undergone a profound decline in the last century. A compelling assumption has become consolidated: as societies become more civilized, religion’s role in humanity’s collective affairs diminishes and is relegated to the private life of the individual. Ultimately, some have speculated that religion will disappear altogether.

Yet this assumption is not holding up in the light of recent developments. In these first decades of the 21st century, religion has experienced a resurgence as a social force of global importance. In a rapidly changing world, a reawakening of humanity’s longing for meaning and for spiritual connection is finding expression in various forms: in the efforts of established faiths to meet the needs of rising generations by reshaping doctrines and practices to adapt to contemporary life; in interfaith activities that seek to foster dialogue between religious groups; in a myriad of spiritual movements, often focused on individual fulfillment and personal development; but also in the rise of fundamentalism and radical expressions of religious practice, which have tragically exploited the growing discontent among segments of humanity, especially youth.

Concurrently, national and international governing institutions are not only recognizing religion’s enduring presence in society but are increasingly seeing the value of its participation in efforts to address humanity’s most vexing problems. This realization has led to increased efforts to engage religious leaders and communities in decision making and in the carrying out of various plans and programs for social betterment.

Each of these expressions, however, falls far short of acknowledging the importance of a social force that has time and again demonstrated its power to inspire the building of vibrant civilizations. If religion is to exert its vital influence in this period of profound, often tumultuous change, it will need to be understood anew. Humanity will have to shed harmful conceptions and practices that masquerade as religion. The question is how to understand religion in the modern world and allow for its constructive powers to be released for the betterment of all.

Religion renewed

The great religious systems that have guided humanity over thousands of years can be regarded in essence as one unfolding religion that has been renewed from age to age, evolving as humanity has moved from one stage of collective development to another. Religion can thus be seen as a system of knowledge and practice that has, together with science, propelled the advancement of civilization throughout history.

Religion today cannot be exactly what it was in a previous era. Much of what is regarded as religion in the contemporary world must, Bahá’ís believe, be re-examined in light of the fundamental truths Bahá’u’lláh has posited: the oneness of God, the oneness of religion, and the oneness of the human family.

Bahá’u’lláh set an uncompromising standard: if religion becomes a source of separation, estrangement, or disagreement—much less violence and terror—it is best to do without it. The test of true religion is its fruits. Religion should demonstrably uplift humanity, create unity, forge good character, promote the search for truth, liberate human conscience, advance social justice, and promote the betterment of the world. True religion provides the moral foundations to harmonize relationships among individuals, communities, and institutions across diverse and complex social settings. It fosters an upright character and instills forbearance, compassion, forgiveness, magnanimity, and high-mindedness. It prohibits harm to others and invites souls to the plane of sacrifice, that they may give of themselves for the good of others. It imparts a world-embracing vision and cleanses the heart from self-centeredness and prejudice. It inspires souls to endeavor for material and spiritual betterment for all, to see their own happiness in that of others, to advance learning and science, to be an instrument of true joy, and to revive the body of humankind.

True religion is in harmony with science. When understood as complementary, science and religion provide people with powerful means to gain new and wondrous insights into reality and to shape the world around them, and each system benefits from an appropriate degree of influence from the other. Science, when devoid of the perspective of religion, can become vulnerable to dogmatic materialism. Religion, when devoid of science, falls prey to superstition and blind imitation of the past. The Bahá’í teachings state:

Put all your beliefs into harmony with science; there can be no opposition, for truth is one. When religion, shorn of its superstitions, traditions, and unintelligent dogmas, shows its conformity with science, then will there be a great unifying, cleansing force in the world which will sweep before it all wars, disagreements, discords and struggles—and then will mankind be united in the power of the Love of God.

True religion transforms the human heart and contributes to the transformation of society. It provides insights about humanity’s true nature and the principles upon which civilization can advance. At this critical juncture in human history, the foundational spiritual principle of our time is the oneness of humankind. This simple statement represents a profound truth that, once accepted, invalidates all past notions of the superiority of any race, sex, or nationality. It is more than a mere call to mutual respect and feelings of goodwill between the diverse peoples of the world, important as these are. Carried to its logical conclusion, it implies an organic change in the very structure of society and in the relationships that sustain it.

The experience of the Bahá’í community

Inspired by the principle of the oneness of humankind, Bahá’ís believe that the advancement of a materially and spiritually coherent world civilization will require the contributions of countless high-minded individuals, groups, and organizations, for generations to come. The efforts of the Bahá’í community to contribute to this movement are finding expression today in localities all around the world and are open to all.

At the heart of Bahá’í endeavors is a long-term process of community building that seeks to develop patterns of life and social structures founded on the oneness of humanity. One component of these efforts is an educational process that has developed organically in rural and urban settings around the world. Spaces are created for children, youth, and adults to explore spiritual concepts and gain capacity to apply them to their own social environments. Every soul is invited to contribute regardless of race, gender, or creed. As thousands upon thousands participate, they draw insights from both science and the world’s spiritual heritage and contribute to the development of new knowledge. Over time, capacities for service are being cultivated in diverse settings around the world and are giving rise to individual initiatives and increasingly complex collective action for the betterment of society. Transformation of the individual and transformation of the community unfold simultaneously.

Beyond efforts to learn about community building at the grass roots, Bahá’ís engage in various forms of social action, through which they strive to apply spiritual principles in efforts to further material progress in diverse settings. Bahá’í institutions and agencies, as well as individuals and organizations, also participate in the prevalent discourses of their societies in diverse spaces, from academic and professional settings, to national and international forums, all with the aim of contributing to the advancement of society.

As they carry out this work, Bahá’ís are conscious that to uphold high ideals is not the same as to embody them. The Bahá’í community recognizes that many challenges lie ahead as it works shoulder to shoulder with others for unity and justice. It is committed to the long-term process of learning through action that this task entails, with the conviction that religion has a vital role to play in society and a unique power to release the potential of individuals, communities, and institutions.

Although the 20th century witnessed the increasing recognition of principles such as universal human rights, democratic ideals, the equality of human beings, social justice, the peaceful resolution of conflict, and condemnation of the barbarism of war, it was nevertheless one of the bloodiest centuries in all human history. Such a development was unpredicted by classical sociological theorists writing in the second half of the 19th century, who either did not devote much attention to the question of war and peace or were optimistic about the prospects for peace in the 20th century. While war and peace were central questions in the social theories of both Auguste Comte (1798–1857),1Auguste Comte, Introduction to Positive Philosophy (Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1970). the founder of positivism, and Herbert Spencer (1820–1903),2Herbert Spencer, Evolution of Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967). the founder of evolutionary and synthetic philosophy, for example, both conceived of social change as an evolutionary movement towards progress and characterized the emerging modern society as essentially peaceful—one in which military conquest aimed at the acquisition of land would be replaced with economic and industrial competition.3This is part of Comte’s law of three stages. According to this idea, all societies evolve by going through religious/theological, metaphysical/philosophical, and scientific/positive stages. Spencer defined a military society as one in which the social function of regulation is dominant, while in an industrial society the economic function predominates. Other classical theorists generally assumed that war among nations was a thing of the past.4Contrary to the popular perception, Durkheim, Marx, and Weber rarely engaged in a direct discussion of war or peace. Only after the onset of the World War I did Durkheim, Simmel, and Mead side with their own countries and discuss the issue. Such optimism was partly rooted in the relative security of Europe during the 19th century where, between the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 and the onset of World War I in 1914 there was a relatively long stage of peace, interrupted mainly by the German-French war of 1870. However, this security was a mere illusion, accompanied as it was by increasing militarism and nationalism in Europe and the vast scale of war and genocide perpetrated by European powers in their pursuit of colonial conquest in Africa and other parts of the world.

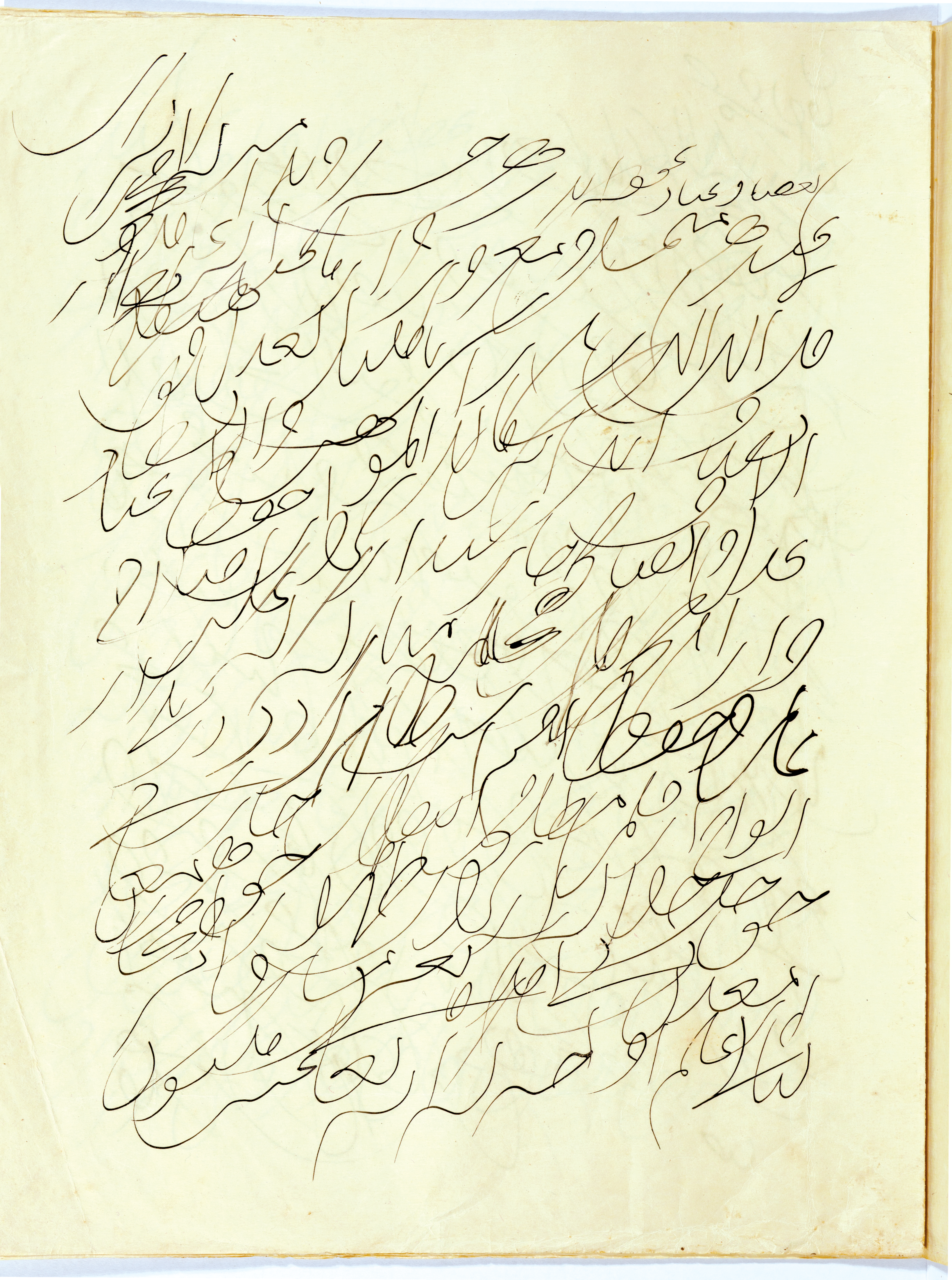

Standing in contrast to the misplaced optimism of the classical 19th century sociologists is the spiritual figure of Bahá’u’lláh, who was born in 1817 in Persia and initiated a transformative global religion centered on the urgency and necessity of peace making. He perceived that both the institutional structures of the 19th century and their cultural orientation promoted various forms of violence, including international wars. The significance of Bahá’u’lláh and His insights as they apply to peace movements and peace studies is evident through an examination of His worldview and of the manner in which His writings reconstruct foundational concepts such as mysticism, religion, and social order—emphasizing the replacement of the sword with the word.

Bahá’u’lláh and the Removal of the Sword

Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alíy-i-Núrí, who took the title Bahá’u’lláh (the Glory of God

), was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1817. As a young man, Bahá’u’lláh accepted the claim of the young merchant from Shiraz known as the Báb (the Gate

) to be the Promised One of Shí‘ih Islam. Both the clerics and state authorities in Iran declared the Báb’s ideas heretical and dangerous and unleashed a systematic campaign of genocide directed at His followers, the Bábís. The Báb Himself was executed in 1850—only six years after the announcement of His mission. While the writings of the Báb provided fresh and innovative interpretations of religious ideas, they pointed to the imminent appearance of a new Manifestation (prophet or messenger) of God and defined His entire revelation as a preparation for the coming of that great spiritual educator. During a massacre of the Bábís in 1852, Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned in a dungeon in Tehran, where He received an epoch-making experience of revelation and perceived Himself to be the Promised One of all religions, including the Bábí Faith. After four months of imprisonment, and the confiscation of all His property, He was exiled to the Ottoman Empire, first to Baghdad, then in 1863 to Constantinople (Istanbul), and from there to Adrianople (Edirne), and finally, in 1868, to the fortress city of ‘Akká in the Holy Land, where He died in 1892.

Although Bahá’u’lláh founded a new religion, the meaning, and particularly the end purpose, of religion is transformed in His writings. As traditionally conceived, religion is often focused on a set of theological doctrines about God, prophets, the next world, and the Day of judgment. While these concepts are discussed and elucidated in His writings, Bahá’u’lláh emphasizes that He has come to renew and revitalize humanity, to reconstruct the world, and to bring peace. In His final work, the Book of the Covenant, He describes the purpose of His life, sufferings, revelation and writings in this way:

The aim of this Wronged One in sustaining woes and tribulations, in revealing the Holy Verses and in demonstrating proofs hath been naught but to quench the flame of hate and enmity, that the horizon of the hearts of men may be illumined with the light of concord and attain real peace and tranquillity.5Bahá’u’lláh, Kitáb-i-‘Ahd (Book of the Covenant), in Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978), 219.

In other words, affirming spiritual principles is inseparable from transforming the social order and from replacing hatred and violence with love and universal peace. From a Bahá’í point of view, then, religion must be the cause of unity and concord among human beings, and if it becomes a cause of enmity and violence, it is better not to have religion.6See for example, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks. Making peace is the essence of Bahá’u’lláh’s normative orientation and worldview. It is ironic, therefore, that both the King of Iran and the Ottoman Sultan rose together against Bahá’u’lláh to silence His voice by intriguing to exile Him to the city of ‘Akká; however, their oppressive decision in the end only exemplified the Hegelian concept of the cunning of Reason,

7Georg W. F. Hegel, Reason in History (New York: Liberal Arts Press, 1953), 25–56. in which Reason realizes its plan through the unintended consequences of actions by individuals whose intent is their own selfish desires. As Bahá’u’lláh has frequently stated, His response to this final exile ordered by these two kings was to publicly announce His message to the rulers of the world. Upon arrival in ‘Akká, He wrote messages to world leaders, including those of Germany, England, Russia, Iran, and France, as well as to the Pope, explicitly declaring His cause and calling them all to unite and bring about world peace. The second irony is that it was through this exile that He was brought to the Holy Land, where the coming of final peace in the world is prophesied to take place, when the wolf and lamb will feed together and swords will be beaten into plowshares.8Isaiah 11:6 and 2:4.

In order to better understand the vital connection between Bahá’u’lláh’s revelation and His concern with peace, let us examine that experience of revelation in the Tehran dungeon in 1852 which marks the birth of the Bahá’í Faith. Bahá’u’lláh describes this experience:

One night, in a dream, these exalted words were heard on every side:

Verily, We shall render Thee victorious by Thyself and by Thy Pen. Grieve Thou not for that which hath befallen Thee, neither be Thou afraid, for Thou art in safety. Erelong will God raise up the treasures of the earth—men who will aid Thee through Thyself and through Thy Name, wherewith God hath revived the hearts of such as have recognized Him.9Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, accessed 7 June 2018, http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/epistle-son-wolf/#f=f2-35

This brief statement epitomizes many of the central teachings of the Bahá’í Faith, one of the most important of which is the replacement of the sword with the word. The victory of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh will take place through the person and character of Bahá’u’lláh and by means of His pen: words and their embodiment in deeds are the only means through which the message of Bahá’u’lláh can be promoted. Thus, the Islamic concept of jihad is abrogated, as is any concept of the religion and its propagation that includes violence, discrimination, coercion, avoidance, and hatred of others. Bahá’u’lláh continually presents the elimination of religious fanaticism, hatred, and violence as one of the main goals of His revelation.

This first experience of revelation defines the substantive message of the new religion in terms of the method of its promotion: A peaceful and dialogical method is the very essence of the new concept of peace and justice. Unlike doctrines that justify forms of violence and oppression as acceptable or even necessary methods of establishing peace and justice in the world, Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings categorically affirm the unity of substance and method in peace making: peace is realized through the way we live, the words we use, and the means we employ to bring about justice, unity, and peace. For Bahá’u’lláh, the time has come to reject the law of the jungle not only in our normative pronouncements about humanity but also in the methods we pursue in order to realize lofty ideals.10See Saiedi, From Oppression to Empowerment,The Journal of Bahá’í Studies 26:1–2 (Spring/Summer 2016), 28–30.

The word, or the pen, is central in Bahá’í philosophy. In the experience of revelation, there is a conversation between God and Bahá’u’lláh, which is an exact repetition of the conversation between God and Moses. According to the Qur’án, God gives two proofs to Moses: His staff and His shining hand. When Moses places His staff on the ground, it becomes a mighty snake, causing Him to become afraid and stand back. God tells Him: Be Thou not afraid, for Thou art in safety.

11Qur’an 28:31. These same words are now uttered by God to Bahá’u’lláh,12While in translation they may appear to be slightly different, they are identical in the original Arabic. implying that the staff of Moses has been replaced by the pen of Bahá’u’lláh as His mighty proof of truth. Likewise, instead of the hand of Moses, the entire being and character of Bahá’u’lláh have become His new evidence. The immediate implication is the unity of Bahá’u’lláh and Moses. This reflects one of Bahá’u’lláh’s central teachings: that all the Manifestations of God are one and that They convey the same fundamental spiritual truth, leading to the principle of the harmony and unity of all religions.

This replacement of the staff with the pen further emphasizes the fact that His cause is rendered victorious through the effect of His words, rather than the performance of supernatural phenomena, or miracles; His message and His teachings constitute the supreme evidence of His truth. This replacement of physical miracles with the miracle of the spirit, namely the Word, is one of the central distinguishing features of Bahá’u’lláh’s worldview. But the most direct expression of the centrality of the pen in Bahá’u’lláh’s revelation is the new definition and conception of the human being offered in this first experience of revelation. The assertion that the cause of Bahá’u’lláh can only be rendered victorious by the pen implies that each soul possesses the capacity to independently recognize spiritual truth. Bahá’u’lláh frequently points out that all humans are created by God as mirrors of divine attributes, and because all individuals are responsible for realizing this divine gift, all the writings of Bahá’u’lláh, in one way or another, call for spiritual autonomy; no one should blindly follow or imitate any other in spiritual, political, and ethical issues. That is why priesthood has been eliminated in the Bahá’í religion and all Bahá’ís are equally and directly responsible before God. The implication of this spiritual autonomy is the utilization of democratic forms of decision making, as characterizes the Bahá’í administrative institutions. However, this form of democracy transcends the materialistic and partisan definition of the prevalent forms in society. Rather, it is a democracy of consultation based on a spiritual definition of reality that views all humans as noble beings endowed with rights.

One final implication of this first experience of revelation needs to be emphasized. According to Bahá’u’lláh’s description, the message of God was brought to Him by a Maid of Heaven. While God, the unknowable, is neither male nor female, the revelation of God through this Word, the supreme sacred reality in the created world, is presented as a feminine reality. Bahá’u’lláh received His revelation not from a tree, a bird, or a male angel, but rather from a female angel who metaphorically symbolizes the inner mystical truth of all the prophets of God. Therefore, the very inception of the Bahá’í revelation is characterized by a fundamental re-examination of the station of women. They are no longer the embodiments and symbols of selfish desires, irrationality, corruption, and worldly attraction; instead, they represent the supreme reflection of God in this world. At the same time, the removal of the sword in this first experience of revelation is a revolutionary critique of patriarchal culture and worldview. These two points are inseparable. The realization of a culture of peace requires the equality and unity of men and women, as violence and patriarchy are inseparable.

From Word Order to World Order

The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh cover a period of forty years, from His imprisonment in the Tehran dungeon in 1852 to His passing in 1892. In the following passage, He describes the purpose and the stages of His writings:

Behold and observe! This is the finger of might by which the heaven of vain imaginings was indeed cleft asunder. Incline thine ear and Hear! This is the call of My Pen which was raised among mystics, then divines, and then kings and rulers.13Bahá’u’lláh, Ishráqát (Tehran: Mu’assisiy-i-Millíy-i-Matbú‘át-i-Amrí, n.d.), 260. Provisional translation.

In the first part of this statement, Bahá’u’lláh presents the contrasting images of the finger of might

and the heaven of vain imaginings

. While the idea of cleaving the moon is attributed to the prophet Muhammad, now Bahá’u’lláh’s pen is rending not only the moon but the entire heaven, which represents the illusions, idle fancies, superstitions, and misconceptions that have erected walls of estrangement between human beings, have enslaved them, and have reduced their culture to the level of the animal. Bahá’u’lláh emphasizes that violence, oppression, and hatred are embodiments of vain imaginings and illusions constructed by human beings. Now, through his pen, He has come to tear away these veils, extinguish the fire of enmity and hatred, and bring people together.

In the second part of this statement, Bahá’u’lláh identifies the stages and order of His words, which were first addressed to mystics, then to divines, and finally to the kings and rulers of the world. His first writings, those written between 1852 and 1859, including the time He lived in Iraq, primarily address mystical concepts and categories.14See The Call of the Divine Beloved: Selected Mystical Works of Bahá’u’lláh (Haifa, Bahá’í World Centre, 2018), https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/call-divine-beloved/. Those of the second stage, encompassing His writings between 1859 and 1867, address the religious leaders and their interpretation of religion. Finally His writings from 1868 on, directed both to the generality of humankind and to the kings and rulers of the world, address social and political questions. Each stage emphasizes a certain principle of Bahá’u’lláh’s worldview, following the sequence of His spiritual logic. The principles corresponding to these stages are as follows: a spiritual interpretation of reality, historical consciousness—even the historicity of the words of God—and global consciousness. The worldview of Bahá’u’lláh is defined by the mutual interdependence of these three principles.

Each stage of the writings of Bahá’u’lláh aims to reinterpret and reconstruct traditional ideas and worldviews. Therefore, the dynamics of His writings can be described by His reconstruction of mysticism, religion, and the social order.

1. Reconstruction of Mysticism

In His earlier writings, Bahá’u’lláh directly engages with Persian and Islamic forms of mysticism; through these and His later writings, He reconstructs mysticism so as to realize its full potential. To understand this point, it is useful to refer to the twin concepts of the arc of descent (qaws-i-nuzúl) and arc of ascent (qaws-i-ṣu‘úd) which comprise the spiritual or mystical journey. The arc of descent is normally perceived as the descent of reality from God—the dynamics of material creation, culminating in the emergence of human life. As a consequence, however, human beings are estranged from their origin and their own truth, which is the unity of God. This yearning for reunion, in turn, initiates the arc of ascent, the mystical journey of the soul’s return to its source. The arc of ascent, as seen, for example, in the Seven Valleys, transcends the realm of conflict and plurality to discover the underlying truth of all reality, namely God.15 The stages of spiritual ascent are frequently referred to as seven valleys or seven cities. In ‘Aṭṭár’s Conference of the Birds these stages are: search/quest, love, knowledge, contentment/independence, unity, wonderment/bewilderment, and annihilation in God. Baha’u’llah’s Seven Valleys employs these stages, but He makes a slight change in the order, bringing contentment/independence after unity. See The Call of the Divine Beloved. With the annihilation of self that is found in this unity, one is assumed to have reached the zenith of the arc of ascent.

Although in traditional views of mystical consciousness, the zenith of the arc of ascent is the highest and end point of the spiritual journey, in reality this is just the beginning of a new stage. But in traditional consciousness all humans become sacred and equal only in God. In other words, only when living human beings, made of flesh and blood, are divested of their various determinations and turned into an abstraction do they become noble and sacred. For example, only when women are no longer women—that is, when their concrete determinations are negated and annulled in God—do they become equal to men. But concrete, living women remain inferior to men in rights, spiritual station, and rank. Thus despite the claim to see God in everything, the presence of social inequalities including slavery, patriarchy, religious discrimination, political despotism, and caste-like distinctions could go unchallenged.

For that reason, we need a further arc of descent

to bring the fundamental insight and achievement of mystic oneness down to earth. In other words, after tracing the arc of ascent and attaining the consciousness of unity, one must be able to descend once again into the world of concrete plurality and time and maintain the consciousness of unity without being imprisoned in the consciousness of conflict and estrangement. In this way, the wayfarer is transformed into a new being who sees the unity of all in the concrete diversity of the world; in this arc of descent, one comes to see in all people their truth, or their divine attributes. The result of this consciousness is the end of the logic of separation, discrimination, prejudice, and hatred, and the beginning of the culture of the oneness of the human race, encompassing equal rights of all humans, the equality of men and women, religious tolerance and unity, and universal love for all people. Thus, according to Bahá’u’lláh, the real task of the mystic is not just the inward transformation of the annihilation of self in God but to transform the world so that the mystical truth of all human beings is manifested in the relations, structures, and institutions of social order. Since all beings become reflections of God, God and his unity are recognized within the diversity of moments and beings, resulting in the worldview of unity in diversity.

2. Reconstruction of Religion

The reconstruction of religion is, in fact, the first stage of the new arc of descent. In this first step, one descends from the unity of God and eternity to the diversity of the prophets and Manifestations of God. Here, history reveals a unity in diversity that reflects in its dynamics the unity of God: the Bahá’í view finds all the Manifestations of God to be one and the same, because they are reflections of divine unity and divine attributes. Since God is defined in the Torah, Gospel, and Qur’án as being the First and the Last, all the Manifestations are also the first and the last.16Examples are Isaiah 44:6 and 48:12, Revelation 1:8 and 22:13, and Qur’án 57:2. They are also the return of each other. Bahá’u’lláh views the realm of religion as the reflection of both diversity (of historical progress) and unity (of all the prophets). He says:

It is clear and evident to thee that all the Prophets are the Temples of the Cause of God, Who have appeared clothed in divers attire. If thou wilt observe with discriminating eyes, thou wilt behold Them all abiding in the same tabernacle, soaring in the same heaven, seated upon the same throne, uttering the same speech, and proclaiming the same Faith. Such is the unity of those Essences of Being, those Luminaries of infinite and immeasurable splendor! Wherefore, should one of these Manifestations of Holiness proclaim saying:

I am the return of all the Prophets,He, verily, speaketh the truth. In like manner, in every subsequent Revelation, the return of the former Revelation is a fact, the truth of which is firmly established.17Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-i-Iqán: The Book of Certitude (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1983), 153–54.

In other words, the Word of God, which is the essence of all religions, is a living and dynamic reality. It is one Word that, at different historical moments, appears in new forms. The different prophets are like the same sun that appears at different times at a different place on the horizon. While the traditional approach to religion usually reduces the identity of the sun to its historically specific horizon and therefore emphasizes opposition and hostility among various religions, Bahá’u’lláh identifies the truth of all religions as one and calls for the unity of religions. In Bahá’u’lláh’s view, a major cause of violence, war, and oppression in the world is religious fanaticism created by the vain imaginings of religious leaders. He warned: Religious fanaticism and hatred are a world-devouring fire whose violence none can quench. The Hand of Divine power can, alone, deliver mankind from this desolating affliction.

18Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, accessed 8 June 2018, http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/epistle-son-wolf/#f=f2-19. The establishment of peace, then, requires overcoming such religious hatred and discord.

3. Reconstruction of the World

The second step of the new arc of descent relates to the wayfarer’s descent into the world. Here, the consciousness of unity necessarily leads to the principle of the oneness of humankind as well as to universal peace. In traditional religious consciousness, the relationship between the created and the Creator is repeated in all forms of social relations. Thus, the relation between men and women, kings and subjects, free persons and slaves, believers and non-believers, and even clerics and laymen repeat the relation between God and human beings. In this way, the illusion is created that domination, discrimination, violence, and opposition are legitimized by religion. In contrast, Bahá’u’lláh explains that the relation that truly obtains is that because all are created by God and are servants of God, all are equal. Instead of repeating in the realm of social order the relation of God to the created world, the servitude of all before God denotes the equality and nobility of all human beings. The task of true mysticism therefore is not to escape from the world, but rather to transform it so that it becomes a mirror of the republic of spirit or the kingdom of God. Bahá’u’lláh’s global consciousness and His concept of peace are embodiments of this reinterpretation of the world and social order, as reflected in the following statement in which He redefines what it is to be human:

That one indeed is a man who, today, dedicateth himself to the service of the entire human race. The Great Being saith: Blessed and happy is he that ariseth to promote the best interests of the peoples and kindreds of the earth. In another passage He hath proclaimed: It is not for him to pride himself who loveth his own country, but rather for him who loveth the whole world. The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.19Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Maqṣúd (Tablet of Maqṣúd), Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, 167.

The purpose of Bahá’u’lláh’s reinterpretation of mysticism, religion, and social order is to bring about a culture of unity in diversity and to institutionalize universal peace in the world. To discuss His specific concept of peace, it is necessary first to review the existing theories of peace in the social sciences and then identify the structure of Bahá’u’lláh’s vision.

Main Theories of Peace

With the outbreak of World War I, most social theorists took the side of their own country in the conflict and, in some cases, glorified war. Georg Simmel identifies war as an absolute situation

in which ordinary, selfish preoccupations of individuals living in an impersonal economy are placed in an ultimate life-and-death situation. Thus, he concludes, war liberates the moral impulse from the boredom of routine life and makes individuals willing to sacrifice their lives for the good of society.20Georg Simmel, Der Krieg und die Geistigen Entscheidungen (Munich: Duncker and Humblot, 1917). On the other side, Durkheim and Mead both take strong positions against Germany. Discussing Treitschke’s worship of war and German superiority, Durkheim writes of a German mentality

which led to the militaristic politics of that country.21Emile Durkheim, L’ Allemagne au-dessus de Tout: La Mentalité Allemande et la Guerre (Paris: Colin, 1915). Emile Durkheim, L’ Allemagne au-dessus de Tout: La Mentalité Allemande et la Guerre (Paris: Colin, 1915). A similar analysis is found in the writings of Mead, who contrasts German militaristic politics with Allied liberal constitutions. In a distorted and inaccurate presentation of Kant’s distinction between the realm of appearances and the things in themselves, Mead argues that in Kantian theory, the substantive determination of practical life is left in the hands of military elites. Such a state could by definition only rest upon force. Militarism became the necessary form of its life.

22G. H. Mead, Immanuel Kant on Peace and Democracy in Self, War & Society: George Herbert Mead’s Macrosociology. Ed. Mary Jo Deegan (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2008), 159–74. However, modern social scientific literature in general and peace studies in particular offer various theories in regard to war and peace, four of which are particularly significant: realism, democratic peace theory, Marxist theory, and social constructivism and cultural theory.

1. Realism

Realism, the dominant theory in the field of international relations, is rooted in a Machiavellian and Hobbesian conception of human beings. According to this model, states are the main actors in international relations. However, the main determinant of a state’s decision to engage in war or peace is the international political and military structure. This structure, however, is none other than international anarchy; the Hobbesian state of nature is the dominant reality at the level of international relations, since there is no binding global law or authority in the world. In this situation, states are left in a situation necessitating self-help, with each regarding all others as potential or actual threats to its security. Thus, arms races and militarism are rational strategies for safeguarding national security. States must act in rational and pragmatic ways and must not be bound by either internal politics or moral principles in determining their policies. In this situation, war is a normal result of the structure of international relations. According to some advocates of this theory, the existence of nuclear weapons and a bi-polar military structure (as seen in the Cold War) are, paradoxically, conducive to peace.23See, for example, John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: Norton, 2001).

2. Democratic Peace Theory

One of the most well-known theories in relation to war and peace is a liberal theory according to which democracies rarely—if ever—engage in war with each other. This doctrine was first advanced in 1875 by Immanuel Kant in his historic work Perpetual Peace.24Immanuel Kant, Perpetual Peace (New York: Columbia University Press, 1939). In contrast to realism, democratic peace theory sees the root cause of war or peace in the internal political structure of societies. Empirical tests have confirmed the existence of a significant positive correlation between democracy and peace,25See Bruce Russet and John R. Oneal, Triangulating Peace: Democracy, Interdependence, and the International Organizations (New York: W. W. Norton, 2001). with two sets of explanations offered. Institutional explanations emphasize the existence of systematic restraining forces in democracies. The vote of the people matters in democracies, and therefore war is less likely to occur because it is the people rather than the rulers who will pay the ultimate price of war. Cultural explanations argue that democracies respect other democracies and are therefore more willing to engage in the peaceful resolution of conflicts. The internal habit of the democratic resolution of conflicts is said to be extended to the realm of foreign relations.26Among classical social theorists there is considerable sympathy for this theory. Durkheim, Mead, and Veblen all identified the cause of World War I as the undemocratic culture and politics of Germany and Japan. Similarly, Spencer finds political democracy compatible with peace.

3. Marxist Theory

Marxist theory can be discussed in terms of three issues: the relation of capitalism to war or peace, the role of violence in transition from capitalism to communism, and the impact of colonialism on the development of colonized societies. The dominant Marxist views on these issues are usually at odds with Marx’s own positions.

Marx did not address the issue of war and peace extensively. He shared the 19th century’s optimism about the outdated character of interstate wars. In fact, he mostly believed that capitalism benefits from peace and considered Napoleon’s wars a product of that ruler’s obsession with fame and glory.27Karl Marx, The Holy Family (Moscow: Foreign Language Pub. House, 1956), Ch. 6. As Mann argues, Marx saw capitalism as a transnational system and therefore regarded it as a cause of peace rather than war.28Michael Mann, War and Social Theory: Into Battle with Classes, Nations and States, in The Sociology of War and Peace, ed. Colin Creighton and Martin Shaw (Dobbs Ferry: Sheridan House, 1987). He believed that violence is mostly necessary for revolution but affirmed the possibility of peaceful transition to socialism in the most developed capitalist societies. Furthermore, Marx saw the colonization of non-European societies as mostly beneficial for the development of non-European stagnant societies, which in turn would lead to socialist revolutions. In the midst of World War I, Lenin (1870–1924) radically changed the Marxist theory of war and peace, arguing that imperialism or the competition for colonial conquest necessarily causes wars among Western capitalist states. According to Lenin, these wars would destroy capitalism and lead to the triumph of socialism. In his view, violence was the only possible way of attaining socialism.29Vladimir I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (New York: International Publishers, 1939).

Marxist theory has inspired many sociological theories of war and peace, from C. Wright Mills’s thesis of the military-industrial complex to Wallerstein’s theory of the world capitalist system.30See C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956) and Immanuel M. Wallerstein, The Politics of the World-Economy: The States, the Movements, and the Civilizations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984). However, in general, most socialist theories see the root cause of war in the extremes of social inequality. Socialism, therefore, is perceived to be the economic order conducive to peace.

4. Social Constructivism and Cultural Theory

A sociological perspective that has influenced the field of international relations is the theory of social constructivism, which systematically criticizes the realist perspective. Emphasizing the symbolic and interpretive character of social relations and practices, this model, which is influenced by symbolic interactionism, states that war is a product of our socially constructed interpretations of ourselves and others. Mead’s emphasis on the social and interactive construction of self is compatible with a host of philosophical and sociological theories that have emphasized the significance of language in defining human reality. Unlike utilitarian and rationalist theories that perceive humans as selfish and competitive, the linguistic turn emphasizes the social and cooperative nature of human beings. Since being with others is the very constitutive element of human consciousness and self, the realization of peace requires a new social interpretive construction of reality.31See, for example, Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Cultural theories emphasize the causal significance of the culture of violence or peace as the main determinant of war or peace. John Mueller argues that prior to the 20th century, war was perceived as a natural, moral, and rational phenomenon.32John E. Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War (New York: Basic Book, 1989). However, through the First and Second World Wars, this culture changed. According to Mueller, the Western world is moving increasingly in this direction, with the non-Western world lagging behind, although the future is bright since we are moving towards a culture of peace.

Bahá’u’lláh’s Approach to Peace

After World War II and the rise of studies focusing on peace as a scholarly object of analysis, authors such as Johan Galtung distinguished between negative and positive definitions of peace, arguing that negative peace

is both unstable and illusory, while positive peace

is true peace.33Johan Galtung, Peace by Peaceful Means (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1996). This preference for the positive definition provided the vision of a different theory of peace. According to the negative definition, war is a positive and objective reality, while peace simply refers to the absence of war and conflict. The positive definition of peace, on the other hand, views peace as an objective state of social reality defined by a form of reciprocal and harmonious relations that fosters mutual development and communication among individuals and groups. In this sense, war and violence indicate the absence of positive peace. Thus, even when there is no direct coercion and armed conflict, a state of war and aggression may still exist.34Concepts like structural, symbolic, and cultural violence are a few expressions of this new conception of the positive definition of peace.

It is interesting to note that both Bahá’u’lláh and His successor ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (1844–1921) systematically and consistently advocate a unique positive definition of peace. Even the word that Bahá’u’lláh uses about the purpose of His revelation (iṣláh) means both reform or reconstruction and peace making. In many of his writings He calls for ‘imár (development) and iṣláh (peace making/reform/reconstruction) of the world.35Shoghi Effendi has translated isláh as security and peace, betterment, ennoblement, reconstruction, and improvement. Similarly , he has translated ‘imár as reconstruction, revival, and advancement. Thus, for Bahá’u’lláh, the realization of peace involves simultaneously a reform, reconstruction, and development of the institutions and structures of the world; mere desire is not a sufficient condition for the realization of a true and lasting peace, which requires a fundamental transformation in all aspects of human existence. While none of the existing theories provides an adequate path towards peace, each pointing only to aspects of the complex question of war and peace, Bahá’u’lláh’s multi-dimensional, positive approach encompasses all the factors addressed by different contemporary theories. The most explicit expression of this is found in His addresses to the leaders of the world, the Súrih of the Temple (Súriy-i-Haykal).36See The Summons of the Lord of Hosts: Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2010). https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/summons-lord-hosts/