In the Lawḥ-i-Dunyá (Tablet of the World), Bahá’u’lláh exhorted humankind to pay special regard to agriculture, emphasizing its vital importance to the advancement of civilization.1Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, 7. Lawḥ-i-Dunyá (Tablet of the World). Available at www.bahai.org/r/512736869 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá further elaborated on this theme in His writings and talks, highlighting the role of the farmer as the “first active agent in human society” and stating that “the question of economics must commence with the farmer and then be extended to the other classes.”2Abdu’l-Bahá, from a Tablet dated 4 October 1912 to an individual believer—translated from the Persian, included in the compilation “Economics, Agriculture and Related Subjects” by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, published in Compilation of Compilations, Volume 3, pages 5-17, 2000.“The fundamental basis of the community is agriculture, tillage of the soil,” He shared on another occasion. “All must be producers.”3Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, Talks in New York, 1-15 July 1912: 77. 309 West Seventy-eighth Street

Little wonder, then, that Bahá’í communities have, throughout the history of the Faith, paid “special regard to agriculture,” especially in the arena of social action. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where approximately two-thirds of the population is engaged in farming on either a full- or part-time basis,4Available at http://www.fao.org/family-farming/regions/africa/en/ the past decades have provided an especially rich opportunity for learning about the application of these teachings in practice. This article reviews developments in recent decades and surveys selected initiatives across the continent, with particular focus on central Africa.

THE RISE OF COLLECTIVE CAPACITY FOR AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

Agriculture is commonly considered to be the backbone of the African economy, contributing between 30 and 60 percent of gross domestic product for each country.5Available at https://www.britannica.com/place/Africa/Agriculture The majority of this production is carried out on family farms less than one hectare in size; in fact, 95% of the farms in sub-Saharan Africa are smaller than five hectares.6Available at http://www.fao.org/family-farming/regions/africa/en/ For the most part, these farms operate at a subsistence level to feed the family and serve local markets. There are limited or no means to irrigate or to access costly inputs such as improved seed varieties, fertilizers, pesticides, or mechanized equipment. Yet despite a large percentage of the population being engaged with agricultural production activities, food security continues to be a challenge for the continent.7Among the factors threatening food security are population growth and the related issue of land shortage; the impact of climate change on rainfall and temperature patterns; soil infertility, partly caused by popular trends pushing farmers away from their traditionally diverse systems of production as well as the dependency the trends have created for chemical fertilizers that lose their effect over time; difficulties of controlling pests that have become resistant to the inorganic pesticides; the disappearance of local varieties of seeds from communities; the lack of quality in seeds purchased in the market with low germination rates; and conflict and epidemics that hinder populations of affected countries from producing and accessing food.

Bahá’í communities in Africa have historically been dedicated to the process of agricultural development. They have established schools that have specifically offered technical training in agriculture, both to build capacity and to develop a love for the field. They have formed village farmers’ groups that have worked together to enhance production and increase income. They have established organizations with the aim of building the capacity of farmers in various aspects of crop and animal production as well as value addition. Some of these efforts have gradually gained strength while others have dissipated over time owing to limited human or other resources. Yet, the sincere desire to work collectively towards agricultural development has remained a constant thread.

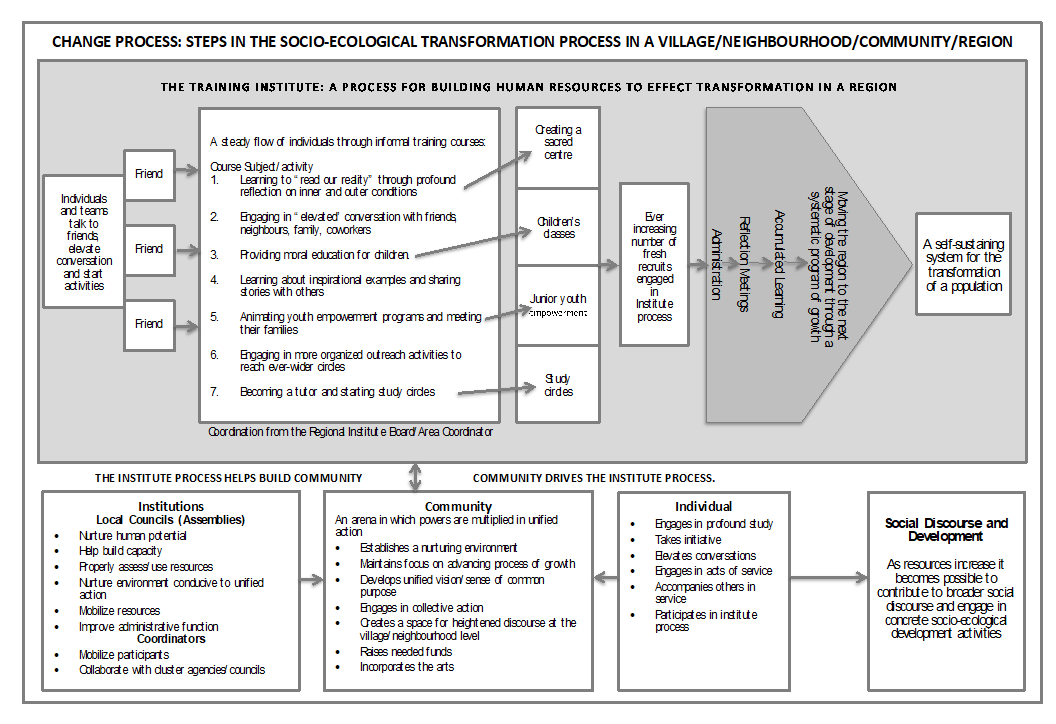

By 2010, as a result of nearly a decade and a half of systematic activity, populations in a number of countries in Africa developed greater collective capacity to address their social and economic needs, including production. At the center of this process was a system of distance education offered by Bahá’í training institutes and the strong spiritual foundations they laid in community after community. Complementing the efforts of institutes were several Baha’i-inspired organizations—supported by the Office of Social and Economic Development—that were gaining experience offering training to youth and adults, assisting them to contribute more systematically to advancing various aspects of the social and economic life of their communities.8Two programs were especially promising in their ability to empower youth and adults to contribute to the well-being of their communities: the Preparation for Social Action (PSA) program and a program for the promotion of community schools.

In hundreds of localities across the continent, this rise in capacity naturally made possible a wide variety of efforts in the area of social action, including in agriculture. For example, conversations among teachers and parents at community schools about the nutritional needs of children often led to the establishment of school gardens or farms. Consultations among groups of youth, learning about promoting the overall well-being of their communities, resulted in the creation of small-scale production projects. A pattern of study, consultation, action, and reflection—which was by now a hallmark of Baha’i activity worldwide—increasingly came to characterize agricultural efforts. Such developments helped create conditions for an increasingly systematic, community-led engagement in the area of agriculture.

DRAWING INSIGHTS FROM THE EXPERIENCE OF FUNDAEC

A number of Bahá’í-inspired organizations on the continent began to consider how to respond to the emerging capacity in the area of agriculture in a way that would be coherent with the process of community building and spiritual transformation already underway.

The insights generated by Fundación para la Aplicación y Enseñanza de las Ciencias (Foundation for the Application and Teaching of the Sciences, FUNDAEC) in Colombia were particularly valuable in this regard. Decades of experience with participatory agricultural research carried out with farmers of the Norte del Cauca region had enabled the organization to develop educational materials that would serve as both a record of this experience as well as tools for the generation, application, and dissemination of new knowledge specific to the context of given community. Among the educational materials, two units—“Planting Crops” and “Diversified High-Efficiency Plots”—were already included in the Preparation for Social Action (PSA) program being implemented in some countries in Africa as well as in the training offered to teachers of community schools.9The PSA program is centered on helping participants acquire capabilities in language, mathematics, science, and processes of community life including education, agriculture, health, and environmental conservation. The units are dedicated to building capacity to enhance food production on small farms, encouraging participants to engage in a process of action-research with their community.10For more information about FUNDAEC’s programs and its experience in agriculture, relevant publications can be found on its website, at www.fundaec.org

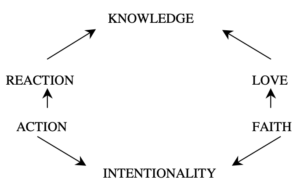

As part of the study, participants are assisted to reflect on the significance of agriculture for society and on the two sources of knowledge essential for the farmer: modern science and the experience of the farmers of the world. They explore the question of technological choice and its implications to the well-being of a community. They study the basics of plant biology, soil science, hydrology, entomology, plant pathology, and various options for water, pest, disease and weed management. They learn how to prepare compost and other organic fertilizers, how to establish and maintain a seed bank, and how to determine the nutritional content of a harvest. They reflect on questions about the value of hard work and collaboration, spiritual qualities needed in working in a group, and how the land is a living thing that needs to be cared for and protected. Above all, students engage in continuing conversations with farmers around them to learn from their experience and share new insights—an approach that encourages an ongoing community-level dialogue about production as well as agricultural science and technology.

The study of the two units among youth and adults in hundreds of localities across the continent gave rise to many initiatives and an increasingly rich conversation at the local level about various processes related to agricultural production. For those organizations that were being gradually drawn into the area of agriculture, building on the learning processes initiated in the units was a natural place to start. Through the encouragement of the Office of Social and Economic Development, a number of these agencies began to interact with one another more regularly in order to learn from each other’s experience and to begin thinking collectively about the challenges before them.

BUILDING THE SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL CAPACITIES OF FARMERS

This emerging network of organizations envisioned a long-term process of learning in the area of agriculture. The central aim, in addition to helping achieve food security, would be to build the scientific and technological capacities of farmers—vital to any long-lasting transformation in production processes and the village economy. In recollecting the evolution of agriculture in their respective countries, the organizations expressed their concerns about the sense of powerlessness felt by many farmers—especially those working on a small-scale—against the economic, social, and environmental factors that influenced their production and forced them to follow systems promoted by whichever organization would provide them with needed inputs at any given time. They further noted that local knowledge related to traditional systems of polyculture was being lost in an increasing number of communities. An effective program to empower the farmers in their respective regions would need to revive this knowledge and methods while also benefiting from the power of modern science.

Inspired by the words of Bahá’u’lláh that all human beings have been created “to carry forward an ever-advancing civilization”11Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, no. CIX, the organizations saw the farmers as partners in a process of generating, applying, and disseminating relevant agricultural knowledge, striving to establish approaches that would avoid the treatment of rural populations as mere consumers of technological packages developed outside their context. They were highly conscious of the fact that such a process would need to be rooted in participatory local action.

LEARNING ABOUT ELEMENTS OF AN ALTERNATIVE SYSTEM OF PRODUCTION

To meet its goal of building the scientific and technological capacities of farmers, the study of the units “Planting Crops” and “Diversified High-Efficiency Plots” by the participants needs to move beyond the theoretical; each participant or group has therefore been encouraged by the organizations to put various of its elements into practice through the establishment of a “diversified high-efficiency (DHE) plot”. This research plot is often between 500 and 2,000 square meters in size; where land is scarce, as in peri-urban settings, the participants establish backyard gardens using readily available containers.12The groups choose the crops they wish to grow on the basis of their study of factors relevant to crop association; they make decisions about irrigation and management of soil fertility, pests, and diseases; they determine how they will use the harvest; and, once harvesting is complete, they weigh the advantages of the system they have established with common systems of both monoculture and polyculture in their microregion. Factors include nutrient content, use of space, time and labor, and degree of risk. They set up a sequence of tasks and draw detailed designs and document the number of hours and the number of inputs spent in each step. They regularly write down their observations about the health of the plot with the aid of a diary. The establishment of raised beds and planting of seeds are carried out with great precision to ensure maximum efficiency of space and resources. While the different parts of the production process are each given due attention, the students are guided not to isolate any one factor but to view the plot as one ecosystem in which the different components are interdependent.

The production cycle—which lasts for a minimum of six months—enhances the capacities of the participants to observe, to plan and generate questions of learning, to make appropriate choices from among a number of alternatives after weighing costs and benefits, to create and use tools to collect data and document, to analyze the results of their observations and experiments and reach conclusions, to, in the final analysis, follow a dynamic process from its beginning to its end. Further, as those engaged in this action-research converse with farmers and involve them in their activities, such capacities, which are relevant not only to the field of agriculture but to all processes of community life, begin to permeate, gradually influencing the way farmers in a community approach their work.

Although the design of DHE plots vary from region to region, there are fundamental criteria for all.13Farzam Arbab, Gustavo Correa and Francia de Valcarcel, “FUNDAEC: Its Principles and Its Activities”. Published by CELATER: Cali, Colombia, 1988. For instance, such plots aim at addressing household food security. They need to be self-sufficient and sustainable, minimizing the use of costly inputs while at the same time providing stable and maximal yields. The plots must also conserve and enhance a farm’s natural resources, especially the soil. Other criteria include efficient use of space, even distribution of the time, resources, and energy required from the farming family over the course of the year, and regulation of income throughout the year to prevent periods of excess and deficit. And perhaps most critically, the systems and approaches need to consider the well-being of a whole community, thus encouraging collaboration rather than competition among families.

GLIMPSES FROM ACROSS AFRICA

Already, thousands on the African continent in around 15 countries have studied at least one of FUNDAEC’s agriculture units, resulting in a large variety of initiatives to implement and promote the approaches contained in the units, as well as an expanding dialogue about questions related to agricultural technology and production. Most of these efforts are at a small-scale; some have grown in size and complexity. In a handful of countries, organizations have been building their capacity to follow a systematic research program.

Their impact, while still nascent, can already be discerned on a number of fronts. Many organizations have observed, for example, a gradual shift in attitudes among young people towards agriculture, with greater value being placed on this vital process of community life. Further, in a growing number of communities, the organizations are describing how members participating in their programs have been adopting a more thoughtful approach to considering the advantages and disadvantages of various technological proposals.

In Uganda, for instance, a group of youth that was approached by a development organization promoting maize monoculture systems requiring high use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides asked the organization’s representative numerous questions about the long term economic and environmental implications of the system; in the end, the group decided not to adopt it and shared with their tutor that they will no longer blindly follow the popular systems of the region. Another group reached out to village leaders and mobilized the community to construct a borehole on a piece of land donated by a group participant, providing water to sustain their experimental plot; group members also agreed to work on each other’s plots to ensure that all had time to study. The organization implementing the PSA program in the country, Kimanya-Ngeyo Foundation for Science and Education, established a large agricultural research farm, organizing training seminars and reflection spaces for tutors and participants to share their experiences with their plots. They further guided the program’s tutors to work with former and current participants as well as community members to establish similar research plots in each region where the program is being implemented.

In Zambia, Inshindo Foundation carried out a campaign to promote backyard gardens in Kabwe, and 50 households adopted the practice. Follow-up efforts will examine how households’ production of food impacts their income and overall wellbeing. The agronomists of the Foundation are in a continuous dialogue with more than 500 farmers, many of whom have studied the agriculture units of the PSA program. The organization has recently launched a Center for Community Agriculture, where farmers from the community can study, consult, and experiment with different systems; the Center includes a local library, a seed bank, and a simple laboratory accessible to the community.

In Cameroon, several former and current participants of the PSA program offered by Emergence—a Baha’i-inspired agency in the country—established an association through which they undertake collective activities, including many in agriculture. In the eastern region, which has received a large number of refugees from Central African Republic, participants have entered into crop production and animal husbandry with the refugees to assist them in addressing their dietary and financial needs.

In the Central African Republic and Malawi, the plots established around Bahá’í-inspired community schools have centered on the nutritional needs of the children and have provided a laboratory for classrooms to study biological sciences. Further, many farms neighboring the schools have adopted the practices implemented on their learning plots.

While such stories abound on the African continent, given the complex and long-term nature of this sphere of endeavor, it would be premature to state that significant changes to production processes have resulted from these efforts. Nevertheless, an example from the south Kivu region of Democratic Republic of the Congo gives us a glimpse of a community that demonstrates the power of collective will to transform agricultural systems, grounded in spiritual principles and a systematic process of study, consultation, action, and reflection.

REACHING THOUSANDS: INITIAL INSIGHTS FROM THE KIVU REGION, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Fondation Erfan-Connaissance, based in Bukavu, Democratic Republic of the Congo, has been offering its teacher-training program to promote the establishment of community schools in the Kivu region since 2007.

Following nine years of activity in the area of primary education, in 2016 the organization began to incorporate the two agriculture units of the PSA program in its teacher-training seminars, first offering them to its 31 facilitators and then to the 185 teachers whom they had been accompanying. The organization hoped that the study of the units would help in three areas: to build the scientific capacities of the teachers, to develop the capabilities needed to converse with families of their students about questions related to production and nutrition, and to improve their production systems and increase their income, especially in villages where teachers are also farmers. In schools with sufficient resources and capacity, DHE plots would be established to grow food for the students and serve as a learning space for both the students and the farming families in the community.

Soon after the first training seminar on the agriculture units, six schools established DHE plots, including one in the village of Canjavu in south Kivu—a number that has since multiplied. In the urban area of Goma in north Kivu, the teachers’ conversations with students and their families led to the establishment of around 80 backyard gardens. The influence of the training teachers received also led to other community agriculture initiatives, including a large seed bank project based in the Nshimbi village in south Kivu. Now, more than 1,000 individuals are engaged in some form with the DHE plots and backyard gardens and another 1,500 have been reached through seed distribution by the Nshimbi seed bank and dissemination of a number of technologies used in DHE plots among neighboring households, especially in Canjavu.

BACKYARD GARDENS, GOMA

The national primary curriculum of the Democratic Republic of the Congo contains basics of agricultural science. However, especially in urban areas where the value given to agriculture is increasingly lost and farming is viewed as the work of the uneducated, it was common for teachers of community schools to move quickly past lessons related to the topic. Following the initial training on the two PSA agriculture units in 2016, however, Fondation Erfan-Connaissance noticed a rise in appreciation for agriculture among the teachers in Goma and an increase in their engagement with students about the subject. Although it was difficult for most schools there to establish plots—Goma is a volcanic area and the size of land available to schools and households is very small—a few schools with sufficient resources were able to begin cultivating crops, from which the students learned about the process of plant growth.

As a result of conversations about production in and outside the classroom, a number of students approached their parents to ask whether they could plant some crops in their backyards. This effort was also supported by the teachers and program coordinators during their visits to the households. In most cases, the parents helped with obtaining the seeds, and the students began to take care of the crops. Within a period of around one year, some 80 backyard gardens had been established. The teachers regularly visited their students’ gardens and witnessed not only the rise in their capacity to manage their garden but also greater evidence of qualities such as patience, determination, and generosity.

Gradually, the coordinators of the teacher-training program in Goma began to observe changes in the nature of interactions between families in neighborhoods with backyard gardens. Households began to exchange planting materials and share experience and advice. In one neighborhood, six families began to collaborate very closely in their production activities, growing medicinal plants as well as food crops.

Further, as the work on gardens continued, the families were able to supplement their income by selling their produce in the local market. In response to the growing interest in urban farming, and to encourage more to engage in the process, two of the Bahá’í-inspired community schools established seed banks, and one began to provide seedlings to five other community schools as well as a number of teachers and community members. Agriculture became an essential topic of conversation during parent-teacher meetings at schools, and reflection meetings focusing specifically on production emerged with an average participation of 120 individuals.

COMMUNITY SEED BANK, NSHIMBI VILLAGE, SOUTH KIVU

The village of Nshimbi is a center of intense Bahá’í community building activity; there are approximately 250 residents who participate regularly in devotional meetings, 280 children who attend Bahá’í children’s classes, around 140 participants in the junior youth spiritual empowerment program, and about 90 engaged in study circles. To respond to the academic needs of the children, a Bahá’í-inspired community school was established in the village in 2016.

After receiving training on the two PSA units on agriculture, one of the teachers, accompanied by the agronomist of the Foundation, started a conversation with the village chief and community members about the need to diversify production systems and establish a local seed bank. The chief convened a meeting with the participation of over 500 individuals, and as a result of the consultation, the community decided to allocate two plots with a total area of approximately 12,000 square meters for the production of seeds and cuttings of a large variety of species. Further, each family was encouraged to establish a vegetable garden to diversify locally available products.

As these efforts gained momentum, the community approached a development organization promoting seed banks to help in the construction of a small building for the bank; the community contributed bricks, sand, and labor, while the organization donated cement and metal sheets. A structure of 35 square meters was thus constructed within a few weeks on a piece of land donated by the chief. In addition, the community put together an administrative arrangement to oversee the bank’s operations.

Among the 25 families that initially made up the bank’s membership, three committees were formed—a management committee to organize meetings and handle the bank’s records, a monitoring committee to distribute the seeds and help members of the community with aspects of cultivation so that they could meet their commitments to the bank, and an advisory committee, of which the village chief would be a member, to protect the initiative from moving in undesirable directions. Further, a number of solidarity groups emerged around the bank focusing on the sale of the agricultural products, on animal husbandry, and on adult literacy. The families would obtain a certain amount of seeds as a loan and would return it with an interest rate that differed from crop to crop; for maize, for instance, the farmer was to return 1.5 kilograms of seed for every kilogram borrowed. Within one year, the number of families who were members of this committee increased from 25 to 200, joining from eight neighboring communities.

In a recent reflection meeting, a mother commented that the seed bank was addressing the problem of malnutrition in the village, as families had been planting monoculture systems before its establishment, which limited the number of crops available for household consumption. It was also observed that the participation of women in community consultations has increased. Further, 60 of the 200 families have entered into animal husbandry from the profit they have made by diversifying their products.

MULTIPLICATION OF DHE PLOTS AND SECONDARY PRODUCTION, CANJAVU VILLAGE, SOUTH KIVU

The village of Canjavu is located around 45 minutes west of Bukavu, the capital of the South Kivu province. It has a population of approximately 3,900 divided into around 500 households. As of April 2020, a large percentage of the population in the village was engaged in more than 600 community-building activities inspired by the teachings of the Bahá’í Faith, including 468 devotional meetings, 40 Bahá’í children’s classes, 50 junior youth groups and 42 study circles. These activities assist the community members to develop their spiritual and intellectual capacities and provide social spaces for meaningful conversations. This has, in turn, led to a systematic process of study, consultation, action, and reflection over ways in which they can advance the various processes of community life, including education, health and agriculture.

The Bahá’í-inspired community school serving the village, Ecole Communautaire Muzusangabo, was established in 2011; currently 105 students attend kindergarten through grade 6. During 2016 and 2017, the school’s teachers as well as 45 farmers from the village and three nearby localities participated in training offered by Fondation Erfan-Connaissance. The training led to the establishment of a DHE plot connected to the school to meet the nutritional needs of the students and serve as a source of income for the school, as well as DHE systems on the farms of those participating in the study. In 2019, the participants decided to each accompany three households that had shown interest in establishing diverse systems on their own plots, leading to the establishment of around 100 DHE plots in the village. As a result, during the Covid-19 pandemic, one village resident stated:

During this health crisis, we are not afraid of running out of food because while we are planting, we are also enjoying the harvest of our previous cultivation. In addition, with the closure of schools, our junior youth… prepare their small plots to help their families. They cultivate amaranth whose leaves are excellent for health.14https://www.bahairdc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=154:la-crise-sanitaire-une-source-d-unite-spirituelle-pour-le-quartier-cpa-lubobo-2&catid=137&Itemid=571

Technical assistance from a local Bahá’í-inspired organization allowed the community to expand the scope of its production activities. In addition to food crops addressing dietary needs, they began to cultivate beetroots as a cash crop in order to produce and sell juice. The funds generated from the sale enabled them to purchase school supplies and to address other community needs. They obtained blenders to simplify the juice-making process and a basic milling machine to grind their own flour, producing donuts that have become popular in neighboring towns and villages.

Beyond the increased capacity of the community to engage in collective income-generating projects, a notable outcome of the action-research process has been a rise in the farmers’ scientific and technological capacities.15They have experimented with the effect of Tithonia on production, comparing untreated and treated sections of land, concluding that fertilizers and pesticides made from the plant have notably increased yields. They questioned assumptions regarding which crops grew well in the region and experimented with planting a number of them, including onions that provided a good harvest. They showed determination when the school plot did not produce well one year, questioning the causes and identifying the plot’s distance from the school to be a significant factor preventing regular monitoring; they have since relocated the research plot, which resulted in increased production. The spiritual qualities and the scientific capacities developed by the group, and the resulting rise in their production, have attracted the interest of other households in the village. While DHE systems are running in 100 households, almost all 500 households participate in the village reflection meetings on agriculture, encouraged by the chief.

The story of Canjavu has been spreading within the region. They have received students from nearby universities who wish to learn about their systems, and a member of the community actively engaged in the plot was asked by the representative of a regional agricultural cooperative to visit different communities with her and share the group’s experience and learning. The director of the Bahá’í-inspired school in the village has commented:

The spirit of unity in the village of Canjavu attracts neighboring villages which also want to learn. People see how present evils are overwhelming humanity. They feel that it is time to join any human enterprise that seeks to act in the Light of Unity!16 https://www.bahairdc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=154:la-crise-sanitaire-une-source-d-unite-spirituelle-pour-le-quartier-cpa-lubobo-2&catid=137&Itemid=571

FUTURE PROSPECTS

At the time of writing this article, humanity is experiencing a worldwide pandemic that has not only already caused the loss of hundreds of thousands of souls but has put the livelihoods of millions more into great jeopardy. Africa has not been immune, and the prospect of famines continues to threaten the continent as it does the rest of the world. Restrictions on movement that have reduced the exchange of products between regions and countries have made it ever-more urgent for each and every community to think deeply about the question of food, and communities are questioning the path that has led them towards dependency.

“Be anxiously concerned with the needs of the age ye live in,” are the words of Bahá’u’lláh, “and center your deliberations on its exigencies and requirements”17Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, no. CVI. “For all beings are linked together like a chain;” says Abdu’l-Bahá, “and mutual aid, assistance, and interaction are among their intrinsic properties and are the cause of their formation, development, and growth.”18Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions, no. 46 Can neighborhoods and villages be assisted to consult prayerfully together to determine ways in which they can produce and market their staple foods in collaboration with each other? What would it take for each household in cities and villages to grow food with whatever resources are available to them? Can current systems focusing entirely on cash crops for export be transformed into systems that would also meet the nutritional needs of thousands of a country’s residents? Can the youth of each community, many of whom have thus far chosen to move away from agriculture and rural areas, seeking the promise of a better life in overcrowded urban settings—a promise that very often leads to disappointment—be encouraged and assisted to channel their energies and focus towards advancing agriculture? How can efforts build on the spirit of service that is characterizing an increasing number of communities that have been in touch with the Creative Word? These are the types of questions that are currently being explored by Bahá’í-inspired organizations engaged in agriculture in Africa as they recall the words of Abdu’l-Bahá that the “fundamental basis of the community is agriculture… All must be producers”.

The prestigious biennial Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) International Prize is not a typical architectural award.

An international jury of six highly distinguished architects has to choose a building that stands out for being “transformative within its societal context” and “expressive of the humanistic values of justice, respect, equality, and inclusiveness.” This they have to do from among an extraordinary selection of architectural structures from around the world that have impacted the social life of the communities within which they were built.

This year’s RAIC International Prize of $100,000 was awarded to the Bahá’í House of Worship for South America. The prize money is being dedicated to the long-term maintenance of the Temple. Commissioned by the Universal House of Justice and designed by Canadian architect Siamak Hariri, the House of Worship for South America has become an iconic symbol of unity for Santiago and well beyond. Overlooking the city from the foothills of the Andes, the Temple has received over 1.4 million visitors since its inauguration in October 2016. The House of Worship has not only symbolized unity but it has given expression to a powerful conviction that worship of the divine is intimately connected with service to humanity.

The connection between the built environment and the well-being of society was a preeminent concern for the Jury of the RAIC Prize. Diarmuid Nash, the Jury Chair, explains that three architectural projects were selected as finalists for the transformative impact they had on their respective communities. “The Bahá’í Temple was a community project. Numerous volunteers worked on this project, similar to a way a community project works in a small village, but this was on a global scale.”

“But the Temple went beyond the community,” he continues. “It extended the principles of the Bahá’í Faith—that every person is equal, that every person can come here to reflect and regenerate. It had this impact that rippled beyond the community and attracted more and more people from all walks of life.”

The process of selection was rigorous and extended over six months. Jury members were asked to perform site visits as part of their research and selection process. “We asked Stephen Hodder, former President of the Royal Institute of British Architects and guest Juror, to visit this project,” says Mr. Nash. “We thought he would have a dispassionate eye.”

Mr. Hodder visited the Temple for three days earlier this year and spent a significant amount of time with the local community. He later shared his impressions with the Jury, referring to the House of Worship as “truly transformational, timeless and spiritual architecture, the like of which I have never experienced, and the influence of which extends way beyond the building.”

Speaking about Mr. Hodder’s visit, Mr. Nash says “Stephen said to me that he had not felt such an emotional impact since he had walked into Ronchamp, which is a very famous chapel all of us have visited in our architectural careers. It is a touchstone of modern architecture. He said ‘this goes beyond Santiago, it reaches out to the world.’”

Mr. Hodder in his comments to the Jury shared the following thoughts:

“How can it be that a building captures the spirit of ‘unity,’ a sacred place, or command a prevailing silence without prompting? The interior space spirals upwards vortex-like culminating with the oculus within which is the inscription ‘O Thou Glory of the Most Glorious’. Seating orientates to Haifa and the Shrine of the Báb, the forerunner of Bahá’u’lláh…. But why do people flock to the Bahá’í Temple? Is it the garden, planted with native species and lovingly cared for by volunteers, or the view over Santiago and remarkable sunsets, or the curious object set against the mountains? The Temple is the anchor…At night, the opacity of the cast glass outer skin, and the translucency of the Portuguese marble inverts, and the dome appears to glow ethereally from the inside…. The Temple has not only afforded a focus for the Bahá’í community but in their commitment to ‘service’ also for the neighbourhood and its well being.”

It was not only the impact of the Temple on society but also the nature of its craftsmanship that struck the Jury. “It was lovingly assembled,” says Mr. Nash. “The woodwork, the stonework, and the glasswork—they all have the sense of a hand shaping them, which is remarkable for a project so sophisticated. This had a powerful impact on the Jury. There was this sense that the hand of the community had crafted the outcome.”

In the wake of the award, Mr. Hariri has been reflecting on the endeavour. “Hundreds of people sacrificially worked on this project with great dedication, enormous skill, and put themselves forward at the very frontier of what’s possible in architecture,” he explains.

“The Temple reflects an aspiration. What architects do is put into form aspiration. When you have a chance like this, where the aspirations are so great, it requires the furthest reaches of imagination to meet that challenge.”

The award was presented on 25 October at a ceremony at the Westin Harbour Castle in Toronto. “Above all,” said Mr. Hariri in remarks he made that evening, “our gratitude extends to the Universal House of Justice which was our unwavering source of guidance, courage, and constancy.”

Mr. Nash, who was there, says that as the talk finished people were standing and cheering. “We were all very inspired. It’s a project that has a life of its own. It is supposed to be a building built to last 400 years. I suspect it will go well beyond that.”

Technological change is inherent to human progress. Technology, by definition, serves to augment human capacities and in so doing alters the environment in which we act. In a very real way, social reality and technology co-evolve or are co-constructed. It could be said that the industrial and information revolutions have fundamentally transformed the functioning and conception of human society. Further, the relentless pace of technical and industrial advancement over the last century has redefined the relationship between human beings and the natural world. Technology is a dominant fashioner of reality, influencing social arrangements, goals, and assumptions in a way that profoundly affects collective development, individual behavior, and the ecosystems upon which we depend. Its multifarious impacts thus must be carefully scrutinized.

A major idea emanating from current academic discourse is that technology both shapes and is shaped by social, economic, political, and cultural forces. As one writer has put it, A technology is not merely a system of machines with certain functions; rather it is an expression of a social world.

1David Nye, Technology Matters: Questions to Live With (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 47. Automobiles and road networks, power and communications systems, and the Internet are not simply technical systems but also social processes shaped by social context. Technologies can empower us but may also embody or express existing relations of power and characteristics of culture, reinforce social inequities or pathologies, or manifest ideological or strategic goals.2In relation to reinforcing patterns of social inequity, modern technological infrastructures sometimes are designed or distributed in a manner that does not benefit all populations of a society. Examples of strategic deployments of technology at the national level include large investments in space and military programs. Notably, technology, in the words of one thinker, has become a powerful vector of the acquisitive spirit

; it expresses wants or desires—and sometimes feeds them.3Dennis Goulet, Uncertain Promise: Value Conflicts in Technology Transfer (New York: New Horizons Press, 1989), 24. Our technical choices define a social reality within which the specific alternatives we think of as purposes, goals, uses, emerge.

4Andrew Feenberg, From Essentialism to Constructivism: Philosophy of Technology at the Crossroads, in Technology and the Good Life, eds. E. Higgs, A. Light, D. Strong (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 294–315. Our identity and roles in contemporary society are strongly mediated by technology; it is something we create, but it also recreates or redefines us.

THE CRITICAL ISSUE OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHOICE

Technical choices shape the contours of everyday life and give real definition to modernity. These choices take place at the level of societies as well as individuals. The variety of technologies we confront—and the uncertainty about how best to use them, if at all—is daunting. Further, when we consider complex technical systems that evolve at the macro level, such as the Internet, our ability to influence the overall development and deployment of these systems seems quite limited. Nevertheless, because complex technical systems and the specific components and innovations underpinning them are socially constructed, human volition and values define their purpose and impact. We find, for example, that the intentions and values of a designer or of a corporation behind a product are embedded in ways that often are not obvious. So a simplistic notion that technology is a neutral means to freely chosen ends is not tenable. Technological advancement increasingly shapes the moral terrain on which we make decisions.5As an example, the widespread use of fetal ultrasound technology has impacted decision making regarding childbirth.

For many decades, the subject of technology has been integral to public discourse concerning processes of social and economic development. Various objectives and descriptors have been used to define the appropriateness of technology in relation to development activity: small scale, labor intensive, advanced, intermediate, indigenous, energy efficient, environmentally sensitive. 6The notion of appropriate technology, as technology of small scale that is ecologically sound and locally autonomous was championed by the economist E.F. Schumacher in his work Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, 1973. Ultimately, the appropriateness of technology is determined by the values of those creating, using, or implementing it. The appropriate technology

movement perhaps lost momentum to some degree because the role of values in guiding technological choice was not systematically explored.7Farzam Arbab, Promoting a Discourse on Science, Religion, and Development, in The Lab, The Temple and the Market: Reflections at the Intersection of Science, Religion, and Development, ed. Sharon Harper (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 2000), 149–237.

Technological development often proceeds in a manner decoupled from community values and broader questions of individual and collective purpose. In using technology, means and ends can be easily confused, and consequently community goals and requirements can be wrongly defined.8The One Laptop per Child initiative illustrates the failure to harmonize means and ends. While technical innovation allowed laptops to be produced for slightly more than $200 per device, little or no effort was made to develop pedagogical material utilizing the technology. Initial surveys from Peru, where the laptops were widely distributed in schools, indicate no improvement in educational performance by students apart from learning how to use the laptops. Critics contend that the funds used for the laptops would have been better applied to teacher training. See, The Failure of One Laptop per Child, http://hackeducation.com/2012/04/09/the-failure-of-olpc. When the link between material needs and values is ignored, the role of technology as a vehicle for upraising the human condition becomes supplanted by a process that often turns people into passive subjects rather than active users and shapers of technological instruments.

Any tool can be used productively or destructively. But the most serious consequences of technology use are often quite subtle. The rapid adoption of new technology without reflection about possible impacts has sometimes upended longstanding social and cultural patterns, where entire domains of meaning and purpose in traditional cultures are displaced.9See, for example, the case of the Skolt Lapps, Pertti J. Pelto, The Snowmobile Revolution: Technology and Social Change in the Arctic (Prospect Hts, Ill: Waveland Press, 1987). In such circumstances, technology itself becomes a bearer and even disrupter of values; it can cause individuals and communities to adapt to technology rather than use technology to extend human capability in harmony with social goals and mores. This pattern of reverse adaptation

, where technology structures and even defines the ends of human activity, is a widespread phenomenon.10An illustration of reverse adaptation is that the availability of SMS technology has transformed the nature, frequency, style and substance of personal communication. While SMS texting is undoubtedly a useful tool, in some respects it has also displaced other forms of meaningful communication or created a perceived need on the part of many for the constant sharing of trivial information. Outsourcing our personal decision-making to algorithms is another example of how many people have adapted to new technologies. Such outsourcing is, in a way, a moral choice; we may be gaining efficiency but at the cost of opening ourselves up to forces of persuasion that distort our intentions. The concept of reverse adaptation is discussed in Langdon Winner, Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-control as a Theme in Political Thought (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977), 227–29. The choices we make about technology, then, particularly when not fully evaluating their implications, may be at variance with our essential purposes, ideals, and norms. For this reason, as individuals, families, communities, and societies, we must reflect about how we design and deploy technological tools.

Technology can embed values in several other ways. It encourages that primacy be placed on efficiency, which can result in a failure to recognize negative externalities;11The classic illustration of negative externalities is the failure to take account of environmental impacts of technical innovation or industrial activity. it emphasizes a reductionist approach to problem solving, which can lead to an atomistic versus a systems approach in addressing complexity;12A reductionist approach can be found in the emphasis on recycling versus the reconsideration of systems of production and consumption. The former is obviously easier to pursue than the latter. In relation to particular social needs, there are usually different levels of technical solutions possible, with each succeeding solution having a higher degree of organizational complexity and a more formidable set of institutional and economic obstacles. An example would be the development of a mass transit system in lieu of a system relying on personal transport via automobiles. The adoption of the most optimal solution in terms of efficiency and aggregate environmental impacts—mass transit—requires active engagement and assent of the citizenry affected as it entails a different distribution of social resources. and it fosters an instrumental rationality rather than a rationality concerned with overall quality of life and meaning.13Goulet, Uncertain Promise, 17–22. What is at issue here is a general attitude fostered by a technological way of life where technology and everything it affects become instrumental—a means to an end—but the ends aren’t defined. Technology can prevent us from appreciating what is of true significance in leading a purposeful life, and thus the meaning invested in relationships and other aspects of life becomes diminished. In the end, such an orientation can result in an exaggerated reliance on technology where it is easier to diffuse technology rather than effect change in human attitudes and behavior.14An example of this technological fix mentality is the idea of geo-engineering, which involves intentional, large-scale technical manipulations of the Earth’s climate system either by reflecting sunlight or removing carbon dioxide from the air. Many scientists are concerned about the unknown risks of such approaches to alter complex natural systems. See: Technological ‘Solutions’ to Climate Change, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/geoengineering-solutions/. A facile optimism that technology alone can ameliorate or resolve pressing social challenges often only serves to exacerbate the real problems at stake in a given context.

THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY IN ADVANCING CIVILIZATION

The concept of human betterment, of an ever-advancing civilization in which both material and spiritual well-being are continually fostered, implies a central role for science and technology and, in particular, an evolving capacity for making appropriate technological choices. Such a capacity represents an expression of human maturation. A key concept articulated in the Bahá’í teachings is that the creation, application, and diffusion of knowledge lies at the heart of social progress and development. In the latter part of the 19th century, Bahá’u’lláh urged: In this day, all must cling to whatever is the cause of the betterment of the world and the promotion of knowledge amongst its peoples.

15Bahá’u’lláh, cited in 26 November 2003 letter of the Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of Iran. And in a related passage, He affirmed: The progress of the world, the development of nations, the tranquility of peoples, and the peace of all who dwell on earth are among the principles and ordinances of God.

16Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978), 129. These and other statements in the Bahá’í writings underscore that the set of human capacities necessary for building up the material and moral fabric of collective life is derived from an expanded notion of rationality that references both mind and spirit.

While extolling the power of intellectual investigation and scientific acquisition

as a higher virtue

unique to human beings, the Bahá’í writings recognize that scientific methodologies alone cannot tell us which ideas or norms best advance a specific social objective or competence.17‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912, rev. ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 49. The knowledge required to advance social well-being must be multidimensional, encompassing not only techniques, methodologies, theories, and models but also values, ideals, qualities, attributes, intuition, and spiritual discernment. Drawing on both science and religion allows us to satisfy these diverse knowledge requirements and to identify new moral standards and avenues of learning in addressing emerging contexts of social dilemma.18The harmony of science and religion is an essential Bahá’í tenet: …faith in God and confidence in social progress are in every sense reconcilable…science and religion are the two inseparable, reciprocal systems of knowledge impelling the advancement of civilization (The Universal House of Justice, 26 November 2003). Religion is regarded as an evolutionary and civilizing phenomenon addressing knowledge at two principal levels: first, providing insight concerning human purpose, provenance, and identity; and second, informing us as social beings about the essential parameters of social interaction and the very nature of the social order, particularly how it should be constructed to reflect principles of fairness, empathy, and cooperation. As an essential expression of reality, religion is not to be dismissed as an atavistic phenomenon irrelevant to the processes of social advancement. Rather, it is a primary force shaping human consciousness, ensuring that humanity’s distinctive potentialities, particularly its rational powers, are constructively channeled. This sheds light on the full range of capabilities that must be employed in understanding, developing, evaluating, and using technology. In essence, technology is a magnifier of human intent and capacity, and consequently, it cannot become a substitute for human judgment or action.

The term technology

derives from the Greek techne,

which is translated as craft

or art

. In this sense, technology is the branch of human inquiry and activity relating to craftsmanship, techniques, and practices; to innovation and provision of objects; and to systems based on such objects. While the term technology

is not explicitly used by Bahá’u’lláh or the Báb, we do find references to the arts and sciences,

craftsmanship,

and invention.

Bahá’u’lláh wrote: Arts, crafts and sciences uplift the world of being, and are conducive to its exaltation. Knowledge is as wings to man’s life, and a ladder for his ascent.

19Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), 26. The knowledge referred to here in the original Arabic is ‘ilm. Two principal types of knowledge are alluded to by Bahá’u’lláh: ‘ilm, referring to knowledge gained by the use of reason, investigation and sensory perception, and irfán, referring to spiritual insight, awareness and inner knowledge. That irfán and ‘ilm are deeply connected is underscored by Bahá’u’lláh throughout His writings. For example, He states: The source of all learning (‘ulúm, plural of ‘ilm) is the knowledge of God (irfán Allah). Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, 159. And in a prayer, the Báb wrote: I yield praise unto Thee, O Lord our God, for the bounty of having called into being the realm of creation and invention.

20The Báb, Selections from the Writings of the Báb (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1976), 195. The Báb and Bahá’u’lláh were the Twin Founders of the Bahá’í Faith. The Báb was both the inaugurator of a separate religious Dispensation and the inspired Precursor of Bahá’u’lláh. Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh: Selected Letters (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1991), 123. The deep connection between the rational and creative dimensions of human endeavor is strongly emphasized by Bahá’u’lláh: Erelong shall We bring into being … exponents of new and wondrous sciences, of potent and effective crafts, and shall make manifest through them that which the heart of none of Our servants hath yet conceived.

21Bahá’u’lláh, Summons of the Lord of Hosts: Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2002), 1.67. It is fascinating that Bahá’u’lláh indicates that one principal sign of the coming of age of the human race

will be the mastery of a particular scientific and technological art: the discovery of a radical approach to the transmutation of elements.

22Bahá’u’lláh, Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1993), n. 194. Physicists have transmuted bismuth into gold in minute quantities via particle accelerators but at considerable cost. See: Fact or Fiction?: Lead Can Be Turned into Gold, Scientific American (January 2014), https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/fact-or-fiction-lead-can-be-turned-into-gold/ . It appears that Bahá’u’lláh is alluding to great advances in the science of transmutation. Natural transmutation of the elements via nuclear fusion reactions in stars is responsible for the creation of the most common elements of the universe including helium, oxygen, carbon and iron. Heavier elements such as lead, gold, and uranium result from higher energy reactions associated with supernovas. The notion that something can be changed into something else reinforces the idea that it is not the material thing that is of value but rather the conceptual insight and knowledge that makes such a transformation possible. This is an affirmation of our primary spiritual identity and agency as manifested by the gifts of creative intellect.23The Bahá’í teachings indicate that we have three aspects of our humanness, so to speak, a body, a mind and an immortal identity—soul or spirit. We believe the mind forms a link between the soul and the body, and the two interact on each other. Letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, 7 June 1946, in Shoghi Effendi, Arohanui: Letters to New Zealand (Suva, Fiji: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 89. The noble and fertile powers of the human spirit can be seen in how the roles of the technologist and artist are in some sense equated and seen as central to the process of social advancement: The purpose of learning should be the promotion of the welfare of the people, and this can be achieved through crafts. It hath been revealed and is now repeated that the true worth of artists and craftsmen should be appreciated, for they advance the affairs of mankind.

24Bahá’u’lláh, in Compilation on the Arts, in The Compilation of Compilations, Vol. I (Monavale: Bahá’í Publications Australia, 1991), 3.

In attempting to elaborate the essential characteristics of technology, one prominent analyst offers this description: Technology is a programming of nature. It is a capturing of phenomena and a harnessing of these to human purposes.

25W. Brian Arthur, The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves (New York: Free Press, 2009), 203. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Bahá’u’lláh’s son and appointed successor, observes that all the present arts and sciences, inventions and discoveries man has brought forth were once mysteries which nature had decreed should remain hidden and latent, but man has taken them out of the plane of the invisible and brought them into the plane of the visible.

26‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, 359. These words suggest that technology is more than a mere programming of nature

and that it serves as an evident expression of humanity’s innate intellectual and inventive power. But He also warns about how this power can be distorted or misapplied. Speaking of the malignant fruits of material civilization,

‘Abdu’l-Bahá stresses that human energy

must be wholly devoted to useful inventions

and concentrated on praiseworthy discoveries.

27‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette: US Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 303. Moving towards more conscious and purposeful patterns of technological innovation that are in consonance with the values and aspirations of individuals and communities depends on both practical and spiritual awareness. There is no question, though, as to the pivotal function that science and technology play in effecting constructive social change and unleashing human potential. As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá says: Would the extension of education, the development of useful arts and sciences, the promotion of industry and technology, be harmful things? For such endeavor lifts the individual within the mass and raises him out of the depths of ignorance to the highest reaches of knowledge and human excellence.

28‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Secret of Divine Civilization (Wilmette: US Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1990), 14.

MECHANISMS OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHOICE

How then can individuals and communities be empowered to make meaningful choices about technology? How do we move from being passive technological users or subjects to active agents in constructively shaping patterns of technological development? Clearly, developing the capacity for technological assessment, innovation, and adaptation is vital to social progress. This requires the creation of grassroots, participatory mechanisms that foster a dynamic process of learning about technology. It entails the creation of consultative social spaces where communities can evaluate technological needs, options, and impacts. Langdon Winner observes that both evaluations of technology and the cultivation of lasting virtues that concern technological choice must emerge from dialogue within real communities in particular situations.

29Langdon Winner, “Reply to Mark Elam.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 19, no. 1 (1994): 107. The main challenge in this regard is how to expand the social and political spaces where ordinary citizens can play a role in making choices early on about technologies that will affect them.

30Ibid. The philosopher Albert Borgmann echoes this point by emphasizing that our use of technology has deep implications for our essential relationships—as family members, parents, citizens, and stewards of nature—and consequently it is necessary for us to reassess notions of the good life

so that technology can fulfill the promise of a new kind of freedom and richness

based on deeper human engagement.

31Albert Borgmann, Technology and the Character of the Contemporary Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 248. In short, we need to create opportunities for reflection at all levels of society that allow us to consciously build ways of life that integrate technology into a desirable conception of what it is to be human. And such a conception of human purpose cannot be dictated by prevailing materialistic structures and forces. Making proper technological choices is therefore bound up with processes of social, political, and moral development.

Practices of collective reflection and public consultation would appear to provide precisely the creative mechanisms needed to appraise new technologies in relation to overall personal and community goals. Such practices move us away from simply being for

or against

technology and instead represent a way for generating and applying knowledge in harmony with basic community aspirations. True community empowerment and learning, the bases of real sustainability, require local communities to define their own pathways of material development and progress. Such active and genuine participation, where practical knowledge is gained by the people most affected, lies at the heart of the Bahá’í approach to transforming social conditions and behavior. In the Bahá’í view, the primary task of material and social development activity is the raising of capacity among individuals, communities, and institutions across all regions and cultures, with the goal of a creating a civilization in which there exists a dynamic coherence between the spiritual and practical requirements of life on earth.

32The Universal House of Justice, 20 October 1983, in a letter written to the Bahá’ís of the world, online at: http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages. This vision rejects approaches to development which define it as the transfer to all societies of the ideological convictions, the social structures, the economic practices, the models of governance—in the final analysis, the very patterns of life—prevalent in certain highly industrialized regions of the world. When the material and spiritual dimensions of the life of a community are kept in mind and due attention is given to both scientific and spiritual knowledge, the tendency to reduce development to the mere consumption of goods and services and the naive use of technological packages is avoided.

33Social Action, a paper prepared by the Office of Social and Economic Development at the Bahá’í World Centre, 26 November 2012.

Changing the locus of power in relation to technological decision making—or what one theorist calls the democratization

of technology that takes fuller account of human agency, needs, and values—has many dimensions.34Andrew Feenberg, Questioning Technology (New York and London: Routledge, 1999). Over the long term, communities need to establish institutional processes for systematizing learning about technology. This includes identifying, understanding, and internalizing relevant community values as they apply to the development and use of technologies. After many years of painful experience, it has become evident that the abrupt transfer of technology from outside a community or culture often doesn’t have the desired effect. Such transfers are plainly not sustainable. The process of harnessing and deploying technical innovation takes time. This is why organizational capacity building at the local level, including collective proficiency in pursuing structured research, training, and deliberation, must be a central component of social development practice.

Stated another way, how does a community learn? Apart from individuals acquiring skills, there has to be a learning process where local groups or local centers of technology are not only absorbing but also generating knowledge. Once a process of this kind begins, everything is possible, including the development of informed technological decision making, constructive patterns of technology usage, and invention appropriate to the needs of communities. As one development practitioner underscores, Disseminating technology is easy, nurturing human capacity and institutions that put it to good use is the crux.

35Kentaro Toyama, Can Technology End Poverty?, Boston Review (November 1, 2010), http://bostonreview.net/forum/can-technology-end-poverty .

Examples of such community capacity building and social capital formation abound.36A growing body of research underscores the central role of social capital in fostering economic development, social cohesion, and patterns of public participation. Social capital is an asset, a functioning propensity for beneficial collective action and is determined by the quality of relationships within a group, community or organization. The formation or enhancement of social capital in a community principally depends on the creation of social spaces and institutions that foster changes in thinking, attitudes and behavior—changes that promote collective exchange, learning and action. Research indicates that social capital builds up as a result of discursive or consultative processes in which stakeholders continually work to elaborate a common understanding of collective objectives. Anirudh Krishna, Active Social Capital (New York, Columbia University Press, 2002). In Kenya, the Kalimani Women’s Group, an initiative influenced by Bahá’í principles, employed consultative methods among community members in developing access to safe drinking water for 6,000 people. Public deliberations focused on underlying health needs, invariably leading to issues of clean water access. Through this public goal-setting process, technological options were considered, including the use of subsurface dams—an innovative, appropriate technology. With assistance from technical non-governmental organizations, community members themselves built and maintained dams, and pumping and storage systems. Processes of evaluation and further project planning all flowed from participatory decision-making mechanisms.37See In Kenya, consultation and partnership are factors for success in development, One Country 11, no. 1 (April–June 1999), http://onecountry.org/story/kenya-consultation-and-partnership-are-factors-success-development. This project, like other effective community-driven development initiatives, has demonstrated that technical learning optimally occurs through substantive and sustained social engagement and consultative interaction among key stakeholders. More broadly, mechanisms of accessible, ongoing community dialog can lead to new social understandings and transform arrangements of power affecting community members.38Transforming arrangements of power is intimately tied to social identity and to the primary values of a community. These factors directly affect, for example, local governance structures, the station and role of women, attitudes toward education, and allocation of community resources. Individual and collective behavior naturally change, and in a beneficial way, when attitudes and values become clear through community consultation. Some of the more dramatic development successes in recent years have involved the reaffirmation or redefinition of basic social norms through community dialog—for example, management of local environmental resources or elimination of practices adversely affecting young women and girls. For an overview of the Bahá’í community’s approach to social and economic development, see For the Betterment of the World, http://dl.bahai.org/bahai.org/osed/betterment-world-standard-quality.pdf.

Beyond specific social development initiatives, the global Bahá’í community itself, through its administrative institutions at the local, national, and international levels, has endeavored to utilize emerging technologies in a manner that aligns with goals of collective learning, organic growth, social empowerment and unity. In this respect, individuals and Bahá’í institutions are becoming increasingly aware that the development and use of technological tools must be determined by actual needs, patterns of activity, available resources, and overarching community objectives rather than any potentially novel methods that such tools can offer. A particular concern is that technologically driven approaches, without proper consideration of the reality of the pertinent administrative or community context, can result in solutions that are ineffective or even inconsistent with basic Bahá’í aims and norms. This has been especially true in relation to the introduction and use of information and communication technologies. As the Universal House of Justice, the governing body of the Bahá’í Faith, has stressed: The capacity of the institutions and agencies of the Faith to build unity of thought in their communities, to maintain focus among the friends, to channel their energies in service to the Cause, and to promote systematic action depends, to an extent, on the degree to which the systems and instruments they employ are responsive to reality, that is, to the needs and demands of the local communities they serve and the society in which they operate…In this connection, we are instructed to provide a word of warning: The use of technology will, of course, be imperative to the development of effective systems and instruments…yet it cannot be allowed to define needs and dictate action.

39From a letter dated 30 March 2011, written on behalf of the Universal House of Justice to a National Spiritual Assembly. Accordingly, circumstances in which technological devices and systems might distort individual and collective behavior through unanticipated cultural effects, promote efficiency at the expense of relationship building, lead to social fragmentation and disunity by serving only certain segments of a community, or undermine existing processes of capacity building and community building by diminishing the agency of community actors, would be closely scrutinized by Bahá’ís.40For instance, due to the dominance of technology platforms and tools created in the West, content or applications emanating from that source can have unexpected cultural impacts on communities in other parts of the world. The patterns of communication facilitated by technological tools can also adversely affect the culture of a community. In this respect, Bahá’ís “must aim to raise consciousness without awakening the insistent self, to disseminate insight without cultivating a sense of celebrity, to address issues profoundly but not court controversy, to remain clear in expression but not descend to crassness prevalent in common discourse, and to avoid deliberately or unintentionally setting the agenda for the community or, in seeking the approval of society, recasting the community’s endeavors in terms that can undermine those very endeavors.” From a letter dated 4 April 2018 written on behalf of the Universal House of Justice to a National Spiritual Assembly. The development and use of technology, then, is grounded in essential Bahá’í values and the means by which those values are expressed in actual community practice. In this way, those directly affected by technological instruments become active protagonists in determining how such instruments are applied to local circumstances and needs.

C CONSULTATIVE PROCESSES ABOUT TECHNOLOGY AT ALL LEVELS OF SOCIETY

Experience indicates that taking account of relevant social context and values in conjunction with scientific parameters can move public discourse concerning technology forward. The key is to create settings that conduce to open-minded and engaged assessment of technical issues. An illustration of such an approach is found in the community deliberation processes promoted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in relation to hazardous waste sites. In the case of widespread contamination of groundwater at Cape Cod’s Massachusetts Military Reservation, stakeholder engagement and consultative processes, particularly the involvement of Cape Cod residents with technical experts, overcame initial community objections about the impacts of groundwater remediation strategies. Ongoing refinement and evaluation of remediation approaches led to community consensus and support for the project, as well as the use of renewable energy sources to reduce carbon emissions associated with the cleanup.41Facilitating A Superfund Cleanup on Cape Cod, Consensus Building Institute, http://www.cbuilding.org/publication/case/facilitating-superfund-cleanup-cape-cod. Although this example highlights a deliberative process addressing harmful impacts of previous technical actions and solutions, the value of the deliberative exercise is clear. Public consultative mechanisms can identify paths of inquiry and knowledge generation that can creatively reframe understanding of issues and thereby expand or alter existing viewpoints and inform public opinion, thus overcoming the tendency to resort to ideological predispositions when dealing with complex socio-technical matters.

TECHNOLOGICAL DETERMINISM?

Even with robust deliberation and learning mechanisms, it can be difficult for communities to exercise control over technological trends and forces, especially when new techniques, devices, or systems originate externally, or if market mechanisms dictate particular technological pathways. For instance, specific agricultural methods, types of energy sources, or modes of communication technology can quickly become prevalent before social, ecological, ethical, and economic impacts within a particular local context are understood. Evaluating technologies can be extremely difficult, as is resisting particular technological trajectories. In a global economy of production, cycles of technological development are increasingly rapid, making it challenging even for the appropriate questions about our choices to be formulated by relevant social institutions.

A strategy of participation and awareness is the necessary starting point in preventing seemingly irrepressible technological and market forces from overwhelming individuals and communities. Even though complex socio-technical systems (transport, telecommunications, energy) seem to have monolithic or intractable attributes, suggesting that technology penetrates society in an irreversible or deterministic way, new directions are possible if societies assess options and adopt different technology policies.42The emergence of demand-side management in the energy utility sector—emphasizing and rewarding energy conservation instead of building more power plants—is a significant shift from a few decades ago. The related integration of decentralized renewable sources is also contributing to the transformation of energy systems. These changes in the United States and other countries have been facilitated by changes in regulatory law. It should be noted, though, that the technology policies of governments rarely give explicit attention to social and environmental exigencies, while social and environmental policies rarely take account of technological opportunities. There is a need for greater coherence.This, though, requires immense moral and political will.

Agency or autonomy should not be attributed to technology, for it diverts attention from the human judgments and relations responsible for social change. As Leo Marx observes: As compared with other means of reaching our social goals, the technological has come to seem the most feasible, practical and economically viable

—resulting in neglect of moral and political standards