In 2013, as winter gave way to spring, a group of villagers in Bihar Sharif, some 1,100 kilometers east of Delhi, India, gathered together on the rooftop of one of their homes to discuss the purpose and function of a local Bahá’í House of Worship, for which the planning had recently begun. These families, friends, and neighbors were consulting about what it would mean for their community to have a Bahá’í Temple raised in their midst, dedicated to prayer and meditation, embracing all people equally, regardless of religious affiliation, background, ethnicity, gender, or caste. In a quiet moment, tears welled in the eyes of one elderly resident as he came to understand that his family would be welcome in this special place. For generations, he explained, they had been denied entry to temples.

Unique in its functioning as a universal place of worship, the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár (from the Arabic, meaning “dawning-place of the mention of God”) was founded by Bahá’u’lláh, Who described its role in society in His sacred writings. Within, there are neither idols nor pictures, neither clergy nor preaching, and no calls for contributions. There is no requirement for an intermediary between the worshipper and God. It is open for personal prayer, meditation, and reflection as well as for devotional programs where prayers and passages from sacred scripture are read aloud, chanted, or sung by adults and children, without instrumental accompaniment. There are no formulas to be followed, allowing for diverse expressions of devotion.

THE FIRST MASHRIQU’L-ADHKÁRS IN THE EAST AND WEST

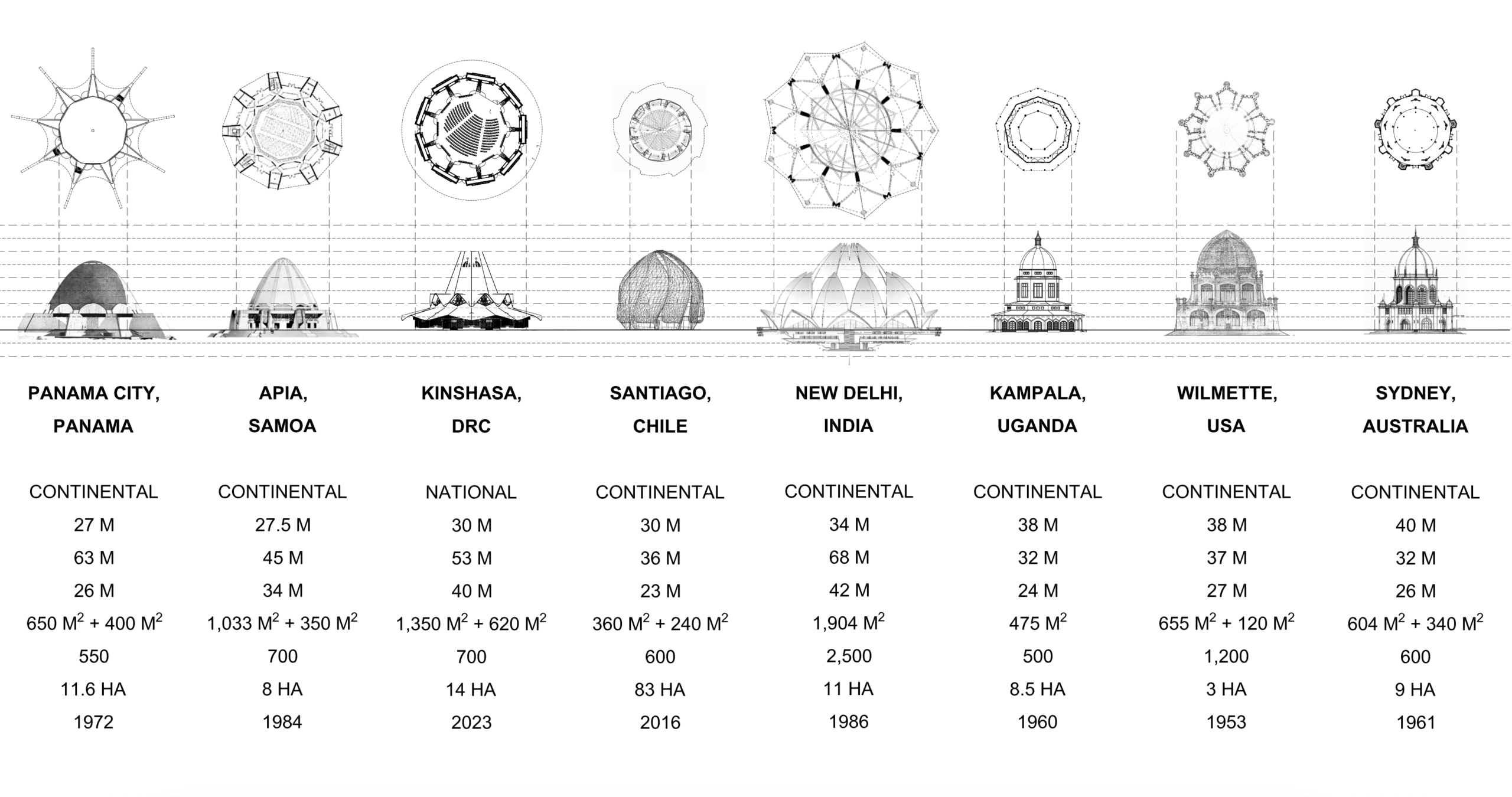

Since the earliest days of the Faith, Bahá’ís have gathered together for collective worship, which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described as an embryonic expression of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. The world’s first Bahá’í House of Worship, in ‘Ishqábád, Turkmenistan, was raised on a parcel of land set aside years earlier at the instruction of Bahá’u’lláh and was fostered at every stage of its development by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Moved by news of the building of the Temple in ‘Ishqábád, the Bahá’ís in North America sought ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approval for a similar project on their continent, which was granted in 1903. The “Mother Temple of the West” at Wilmette, near Chicago, was completed 50 years later.

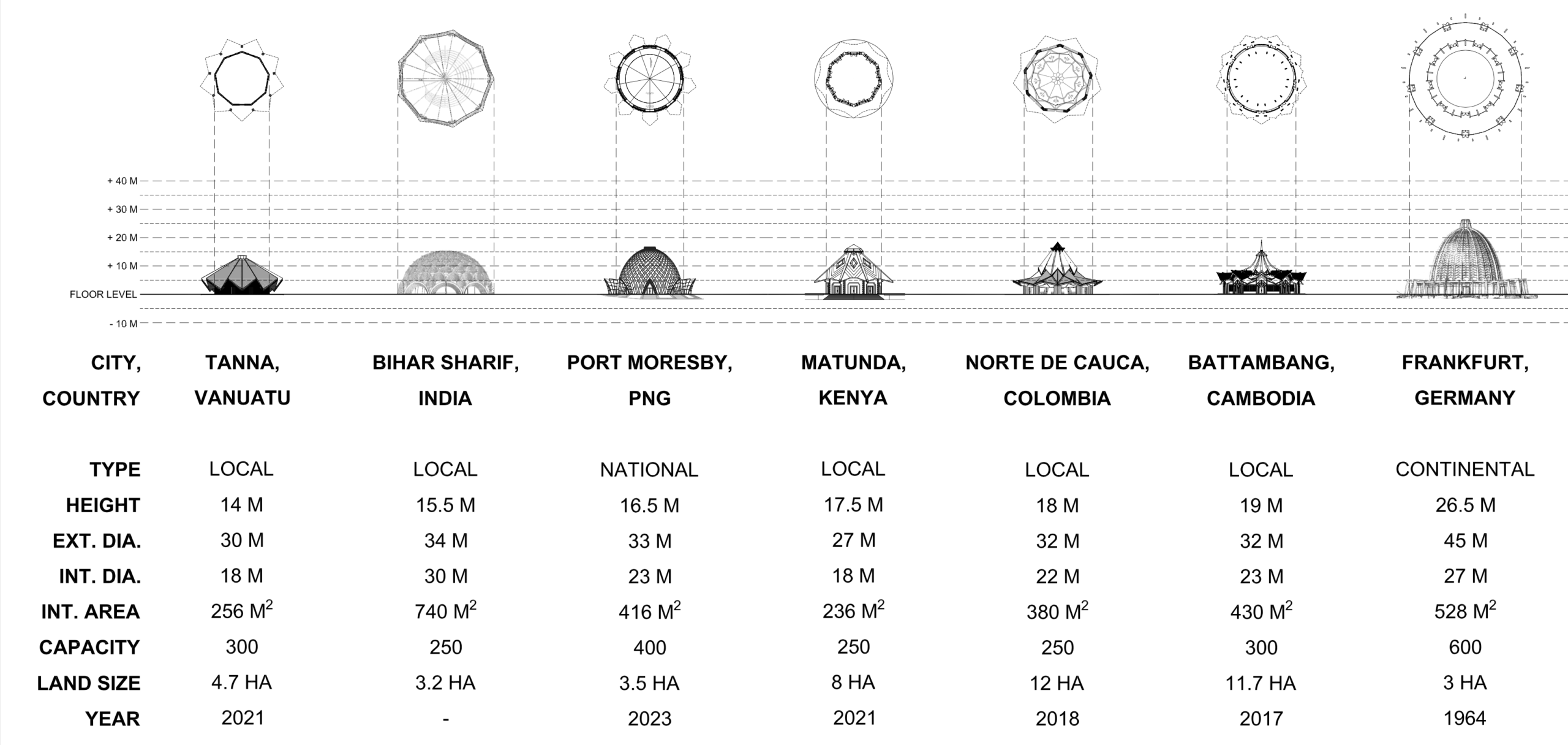

Upon completion of the House of Worship in the United States, Shoghi Effendi initiated two new processes: the construction of continental Temples, in Africa (Kampala, Uganda, completed in 1961), Australasia (Sydney, Australia, completed in 1961), and Europe (Frankfurt, Germany, completed in 1964); and securing land for Temples that would be built in the future. On 8 October 1952, Shoghi Effendi announced that the purchase of land for eleven future Bahá’í Houses of Worship would be an objective of the forthcoming decade-long Plan, along with the acquisition of the site for a future Mashriqu’l-Adhkár on Mount Carmel in the Holy Land. By 1963, some 46 sites for future Houses of Worship had been acquired. Continuing this opening stage of raising continental Temples, the Universal House of Justice proceeded with the building of Temples in Panama City, Panama (1972); Apia, Samoa (1984); and New Delhi, India (1986).

THE EMERGENCE OF NATIONAL AND LOCAL HOUSES OF WORSHIP

Pursuant to Bahá’u’lláh’s instruction “Build ye houses of worship throughout the lands in the name of Him Who is the Lord of all religions,”1The Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book, https://www.bahai.org/r/763968510 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá affirmed that Mashriqu’l- Adhkárs would “be established in every hamlet and city.”2Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, no. 55, https://www.bahai.org/r/681408626

As with all developments in the Bahá’í community, a deliberate and careful approach has been adopted in raising up Temples. For example, although the Temple site in ‘Ishqábád had been prepared for some 15 years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá waited until the means had been secured before permitting the construction to begin, so that the work could proceed without interruption.

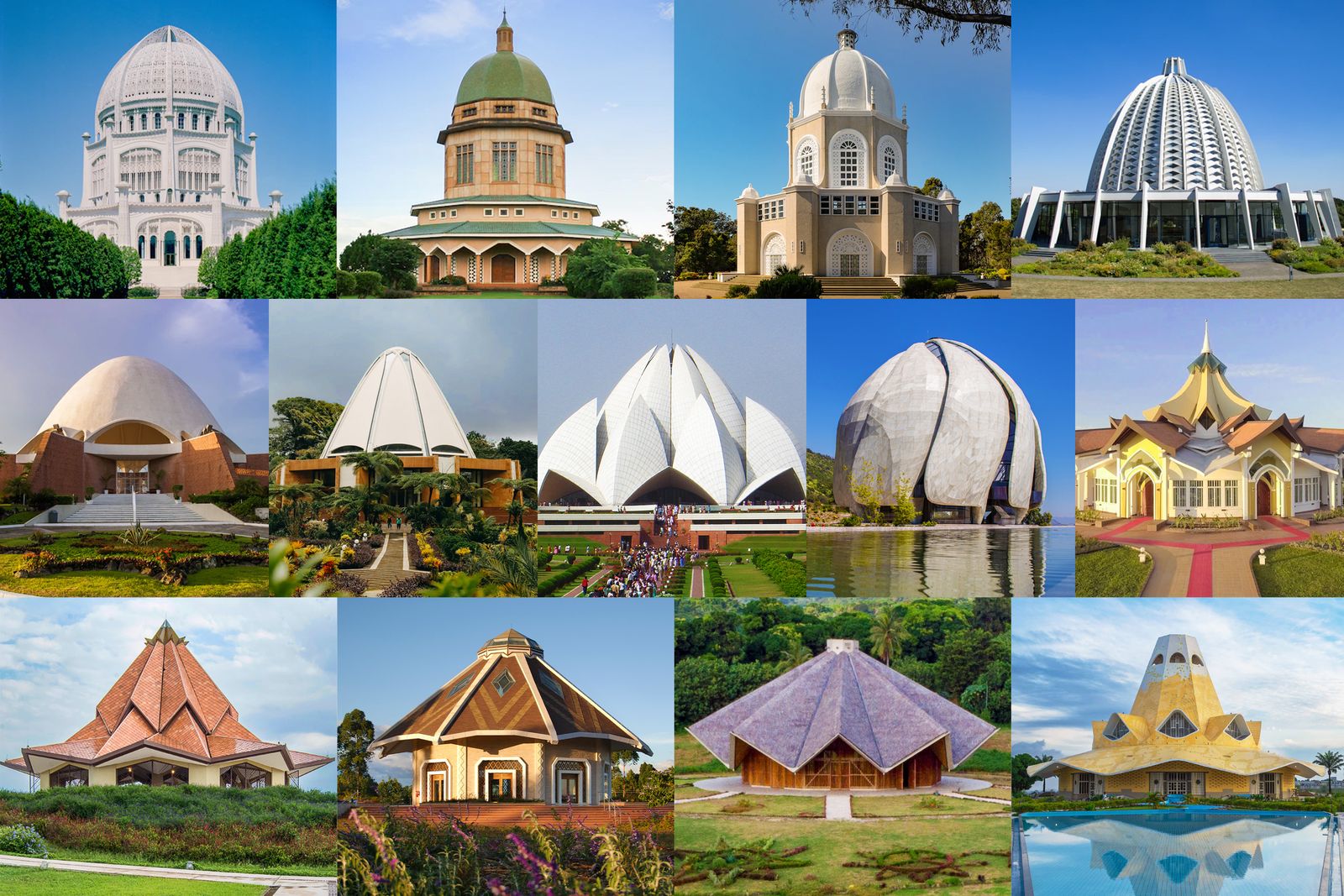

In 1996, at the outset of the 25-year series of plans recently concluded, the Universal House of Justice described the elements of a flourishing community, highlighting the benefits of the practice of collective worship and regular devotional meetings to its spiritual life. However, as critical and transformative as individual and collective prayer may be, worship is not seen by Bahá’ís as an end in itself; rather, it ideally results in “endeavours to uplift the spiritual, social, and material conditions of society” and “deeds that give outward expression to that inner transformation.”3Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the world, 1 August 2013, https://www.bahai .org/r/980781985; Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of Iran, 18 December 2014, in The Institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár, https://www.bahai.org/r/250953299 These two inseparable aspects of Bahá’í life—worship and service—are expressed in the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár.

In one way, this expression can be seen through the role a House of Worship can play as the spiritual center of a community. People, turning their hearts to their Creator, pray and meditate within the Temple and find inspiration and spiritual strength to inspire their actions as they go about all aspects of their life, striving to make their contribution to their family and community. In another sense, the central edifice, in which people gather to pray, can be viewed as an aspect of the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. The process of raising up a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár will continue to develop to a stage where the central edifice will be surrounded by “dependencies dedicated to the social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific advancement of mankind.”4Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the world, 20 October 1983, https://www .bahai.org/r/346303577

In 2001, the Universal House of Justice announced plans to build the last continental Temple in Santiago, Chile. The House of Justice explained that a particular focus of that stage of the Bahá’í world’s development would include the enrichment of communities’ devotional life through the erection of national Houses of Worship.

Eleven years later, in April 2012, when the enterprise in Chile was well underway, the House of Justice announced plans to construct the first two national Houses of Worship in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Papua New Guinea, countries it had determined had experienced vibrant community-building endeavors. The House of Justice further announced that conditions were favorable for the launch of projects to build the first local Houses of Worship. The locations selected were Battambang, Cambodia; Bihar Sharif, India; Matunda Soy, Kenya; Norte del Cauca, Colombia; and Tanna, Vanuatu.

To support the construction of the new national and local Houses of Worship, the Universal House of Justice established two new entities at the Bahá’í World Centre: a Temples Fund to which Bahá’ís around the globe were invited to contribute, and the Office of Temples and Sites, to assist National Spiritual Assemblies whose countries had been selected.

THE COMMENCEMENT OF NATIONAL AND LOCAL TEMPLE PROJECTS

Shortly after the April 2012 announcement, National Spiritual Assemblies began to take practical steps to advance the projects. At the same time, Temple committees were established and began exploring strategies to stimulate awareness about the nature and purpose of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár and what it would mean for a community to house such an edifice. With a vision that the Temple would be for everyone, efforts were made to promote widespread participation among all the people whose lives would be directly impacted. Crucially, communities that had been developing the capacity to operate in a learning mode could now apply that capacity to the process of raising a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár.

Deliberations on the ideal features of Temple land required the balancing of practical and economic factors. This process, diligently undertaken, helped National Assemblies identify strategically located and accessible sites, thinking not only of prominence, but where regular visits to the House of Worship could naturally become part of a pattern of vibrant community life.

In countries where the national community had been in possession of a Temple site for decades, the suitability of the site was reassessed through the same lens. Architects were briefed about the design requirements of a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár—for example, that the House of Worship is nine-sided, circular in shape, and may have a dome. Design specifications called for simpler, more modest designs than those for the continental Houses of Worship. Yet, at the same time, architects would need to ensure that the building’s design would be beautiful and dignified, in harmony with its surroundings and with the cultural context where it would be constructed.

Where possible, local materials and building techniques drawing on generations of experience were given priority, as was an understanding of the native environment. While architects sought inspiration from the principles of the Bahá’í Faith, such as the oneness of humankind and the unity of religions, the design concepts were diverse, ranging from indigenous flowers and plants—for example, the lotus flower or cocoa fruit—to activities that form part of a culture’s identity, such as the practice of weaving. From the outset, the question of ongoing maintenance was carefully considered at the design stage, with the hope that Temples could mostly be maintained through the efforts of the local community.

Within a year of the completion of the Mother Temple of South America in Chile in October 2016, the local House of Worship in Battambang was dedicated in September 2017, followed by the Temple in Norte del Cauca in July 2018. As April 2021 approached, the Kenyan community prepared for the dedication of the local House of Worship in Matunda Soy. Progress continued in all designated locations; the construction of the Tanna Temple was at a late stage, and construction of the national Temples in Papua New Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo had begun. Initial steps to prepare the site in Bihar Sharif had commenced.

As of April 2021, national and local Temple projects ranged from roughly five to nine years from announcement to completion: Cambodia and Colombia within five to six years; Kenya in nine years; Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Democratic Republic of the Congo forecast for nine to eleven years; and India expected to be completed by 2024 or 2025. Construction has been the most consistent stage, ranging from one and a half to two and a half years. The process of land acquisition, at one and a quarter to seven years, and architect selection, at one and three quarters to almost eight years, seem to present the greatest opportunity for optimization, particularly by providing clearer parameters based on experience and simplifying approaches to engaging architects.

REFLECTIONS ON A NEW ERA

The development of the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár during the period under review witnessed the completion of the last of the continental Temples—iconic structures that have, in part, symbolized the establishment of the Faith on all continents. An era has opened in which local and national Houses of Worship are emerging around the world. In such countries and cities where establishing a universally accessible place of worship seems to be a natural step in the development of community life, new opportunities and insights are galvanizing a process of community development already underway.

As Bahá’í communities have become more outwardly focused, planning for construction and operation of future Houses of Worship has begun to take on different dimensions. Those involved in managing the Temple complex and those coordinating community-building activities together are exploring what it means to have the Temple integrated into the pattern of community life. How does the relationship with a House of Worship move beyond the occasional special visit to being interwoven into one’s life, a place for regular meditation, reflection, and prayer? What conditions enable local inhabitants to see the Temple as “our” House of Worship? Do such questions also present an opportunity to revisit more traditional approaches to design and construction, through which they can be aligned to a greater degree with the transformative processes through which populations are taking greater ownership of their own spiritual, intellectual, and, ultimately, social and economic development?

Naturally, local Houses of Worship emerge in communities with burgeoning community-based social and economic development activities. As this process expands, so too will the opportunities to learn about the development of “dependencies dedicated to the social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific advancement of mankind,” a practical expression of the interconnection of worship and service.

On the horizon lies a period of discovery and development through which the influence of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár “on every phase of life” can be realized in ever greater measure.

In the Lawḥ-i-Dunyá (Tablet of the World), Bahá’u’lláh exhorted humankind to pay special regard to agriculture, emphasizing its vital importance to the advancement of civilization.1Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, 7. Lawḥ-i-Dunyá (Tablet of the World). Available at www.bahai.org/r/512736869 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá further elaborated on this theme in His writings and talks, highlighting the role of the farmer as the “first active agent in human society” and stating that “the question of economics must commence with the farmer and then be extended to the other classes.”2Abdu’l-Bahá, from a Tablet dated 4 October 1912 to an individual believer—translated from the Persian, included in the compilation “Economics, Agriculture and Related Subjects” by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, published in Compilation of Compilations, Volume 3, pages 5-17, 2000.“The fundamental basis of the community is agriculture, tillage of the soil,” He shared on another occasion. “All must be producers.”3Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, Talks in New York, 1-15 July 1912: 77. 309 West Seventy-eighth Street

Little wonder, then, that Bahá’í communities have, throughout the history of the Faith, paid “special regard to agriculture,” especially in the arena of social action. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where approximately two-thirds of the population is engaged in farming on either a full- or part-time basis,4Available at http://www.fao.org/family-farming/regions/africa/en/ the past decades have provided an especially rich opportunity for learning about the application of these teachings in practice. This article reviews developments in recent decades and surveys selected initiatives across the continent, with particular focus on central Africa.

The Rise of Collective Capacity for Agricultural Development

Agriculture is commonly considered to be the backbone of the African economy, contributing between 30 and 60 percent of gross domestic product for each country.5Available at https://www.britannica.com/place/Africa/Agriculture The majority of this production is carried out on family farms less than one hectare in size; in fact, 95% of the farms in sub-Saharan Africa are smaller than five hectares.6Available at http://www.fao.org/family-farming/regions/africa/en/ For the most part, these farms operate at a subsistence level to feed the family and serve local markets. There are limited or no means to irrigate or to access costly inputs such as improved seed varieties, fertilizers, pesticides, or mechanized equipment. Yet despite a large percentage of the population being engaged with agricultural production activities, food security continues to be a challenge for the continent.7Among the factors threatening food security are population growth and the related issue of land shortage; the impact of climate change on rainfall and temperature patterns; soil infertility, partly caused by popular trends pushing farmers away from their traditionally diverse systems of production as well as the dependency the trends have created for chemical fertilizers that lose their effect over time; difficulties of controlling pests that have become resistant to the inorganic pesticides; the disappearance of local varieties of seeds from communities; the lack of quality in seeds purchased in the market with low germination rates; and conflict and epidemics that hinder populations of affected countries from producing and accessing food.

Bahá’í communities in Africa have historically been dedicated to the process of agricultural development. They have established schools that have specifically offered technical training in agriculture, both to build capacity and to develop a love for the field. They have formed village farmers’ groups that have worked together to enhance production and increase income. They have established organizations with the aim of building the capacity of farmers in various aspects of crop and animal production as well as value addition. Some of these efforts have gradually gained strength while others have dissipated over time owing to limited human or other resources. Yet, the sincere desire to work collectively towards agricultural development has remained a constant thread.

By 2010, as a result of nearly a decade and a half of systematic activity, populations in a number of countries in Africa developed greater collective capacity to address their social and economic needs, including production. At the center of this process was a system of distance education offered by Bahá’í training institutes and the strong spiritual foundations they laid in community after community. Complementing the efforts of institutes were several Baha’i-inspired organizations—supported by the Office of Social and Economic Development—that were gaining experience offering training to youth and adults, assisting them to contribute more systematically to advancing various aspects of the social and economic life of their communities.8Two programs were especially promising in their ability to empower youth and adults to contribute to the well-being of their communities: the Preparation for Social Action (PSA) program and a program for the promotion of community schools.

In hundreds of localities across the continent, this rise in capacity naturally made possible a wide variety of efforts in the area of social action, including in agriculture. For example, conversations among teachers and parents at community schools about the nutritional needs of children often led to the establishment of school gardens or farms. Consultations among groups of youth, learning about promoting the overall well-being of their communities, resulted in the creation of small-scale production projects. A pattern of study, consultation, action, and reflection—which was by now a hallmark of Baha’i activity worldwide—increasingly came to characterize agricultural efforts. Such developments helped create conditions for an increasingly systematic, community-led engagement in the area of agriculture.

Drawing Insights from the Experience of FUNDAEC

A number of Bahá’í-inspired organizations on the continent began to consider how to respond to the emerging capacity in the area of agriculture in a way that would be coherent with the process of community building and spiritual transformation already underway.

The insights generated by Fundación para la Aplicación y Enseñanza de las Ciencias (Foundation for the Application and Teaching of the Sciences, FUNDAEC) in Colombia were particularly valuable in this regard. Decades of experience with participatory agricultural research carried out with farmers of the Norte del Cauca region had enabled the organization to develop educational materials that would serve as both a record of this experience as well as tools for the generation, application, and dissemination of new knowledge specific to the context of given community. Among the educational materials, two units—“Planting Crops” and “Diversified High-Efficiency Plots”—were already included in the Preparation for Social Action (PSA) program being implemented in some countries in Africa as well as in the training offered to teachers of community schools.9The PSA program is centered on helping participants acquire capabilities in language, mathematics, science, and processes of community life including education, agriculture, health, and environmental conservation. The units are dedicated to building capacity to enhance food production on small farms, encouraging participants to engage in a process of action-research with their community.10For more information about FUNDAEC’s programs and its experience in agriculture, relevant publications can be found on its website, at www.fundaec.org

As part of the study, participants are assisted to reflect on the significance of agriculture for society and on the two sources of knowledge essential for the farmer: modern science and the experience of the farmers of the world. They explore the question of technological choice and its implications to the well-being of a community. They study the basics of plant biology, soil science, hydrology, entomology, plant pathology, and various options for water, pest, disease and weed management. They learn how to prepare compost and other organic fertilizers, how to establish and maintain a seed bank, and how to determine the nutritional content of a harvest. They reflect on questions about the value of hard work and collaboration, spiritual qualities needed in working in a group, and how the land is a living thing that needs to be cared for and protected. Above all, students engage in continuing conversations with farmers around them to learn from their experience and share new insights—an approach that encourages an ongoing community-level dialogue about production as well as agricultural science and technology.

The study of the two units among youth and adults in hundreds of localities across the continent gave rise to many initiatives and an increasingly rich conversation at the local level about various processes related to agricultural production. For those organizations that were being gradually drawn into the area of agriculture, building on the learning processes initiated in the units was a natural place to start. Through the encouragement of the Office of Social and Economic Development, a number of these agencies began to interact with one another more regularly in order to learn from each other’s experience and to begin thinking collectively about the challenges before them.

Building the Scientific and Technological Capacities of Farmers

This emerging network of organizations envisioned a long-term process of learning in the area of agriculture. The central aim, in addition to helping achieve food security, would be to build the scientific and technological capacities of farmers—vital to any long-lasting transformation in production processes and the village economy. In recollecting the evolution of agriculture in their respective countries, the organizations expressed their concerns about the sense of powerlessness felt by many farmers—especially those working on a small-scale—against the economic, social, and environmental factors that influenced their production and forced them to follow systems promoted by whichever organization would provide them with needed inputs at any given time. They further noted that local knowledge related to traditional systems of polyculture was being lost in an increasing number of communities. An effective program to empower the farmers in their respective regions would need to revive this knowledge and methods while also benefiting from the power of modern science.

Inspired by the words of Bahá’u’lláh that all human beings have been created “to carry forward an ever-advancing civilization”11Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, no. CIX, the organizations saw the farmers as partners in a process of generating, applying, and disseminating relevant agricultural knowledge, striving to establish approaches that would avoid the treatment of rural populations as mere consumers of technological packages developed outside their context. They were highly conscious of the fact that such a process would need to be rooted in participatory local action.

Learning About Elements of an Alternative System of Production

To meet its goal of building the scientific and technological capacities of farmers, the study of the units “Planting Crops” and “Diversified High-Efficiency Plots” by the participants needs to move beyond the theoretical; each participant or group has therefore been encouraged by the organizations to put various of its elements into practice through the establishment of a “diversified high-efficiency (DHE) plot”. This research plot is often between 500 and 2,000 square meters in size; where land is scarce, as in peri-urban settings, the participants establish backyard gardens using readily available containers.12The groups choose the crops they wish to grow on the basis of their study of factors relevant to crop association; they make decisions about irrigation and management of soil fertility, pests, and diseases; they determine how they will use the harvest; and, once harvesting is complete, they weigh the advantages of the system they have established with common systems of both monoculture and polyculture in their microregion. Factors include nutrient content, use of space, time and labor, and degree of risk. They set up a sequence of tasks and draw detailed designs and document the number of hours and the number of inputs spent in each step. They regularly write down their observations about the health of the plot with the aid of a diary. The establishment of raised beds and planting of seeds are carried out with great precision to ensure maximum efficiency of space and resources. While the different parts of the production process are each given due attention, the students are guided not to isolate any one factor but to view the plot as one ecosystem in which the different components are interdependent.

The production cycle—which lasts for a minimum of six months—enhances the capacities of the participants to observe, to plan and generate questions of learning, to make appropriate choices from among a number of alternatives after weighing costs and benefits, to create and use tools to collect data and document, to analyze the results of their observations and experiments and reach conclusions, to, in the final analysis, follow a dynamic process from its beginning to its end. Further, as those engaged in this action-research converse with farmers and involve them in their activities, such capacities, which are relevant not only to the field of agriculture but to all processes of community life, begin to permeate, gradually influencing the way farmers in a community approach their work.

Although the design of DHE plots vary from region to region, there are fundamental criteria for all.13Farzam Arbab, Gustavo Correa and Francia de Valcarcel, “FUNDAEC: Its Principles and Its Activities”. Published by CELATER: Cali, Colombia, 1988. For instance, such plots aim at addressing household food security. They need to be self-sufficient and sustainable, minimizing the use of costly inputs while at the same time providing stable and maximal yields. The plots must also conserve and enhance a farm’s natural resources, especially the soil. Other criteria include efficient use of space, even distribution of the time, resources, and energy required from the farming family over the course of the year, and regulation of income throughout the year to prevent periods of excess and deficit. And perhaps most critically, the systems and approaches need to consider the well-being of a whole community, thus encouraging collaboration rather than competition among families.

Glimpses from Across Africa

Already, thousands on the African continent in around 15 countries have studied at least one of FUNDAEC’s agriculture units, resulting in a large variety of initiatives to implement and promote the approaches contained in the units, as well as an expanding dialogue about questions related to agricultural technology and production. Most of these efforts are at a small-scale; some have grown in size and complexity. In a handful of countries, organizations have been building their capacity to follow a systematic research program.

Their impact, while still nascent, can already be discerned on a number of fronts. Many organizations have observed, for example, a gradual shift in attitudes among young people towards agriculture, with greater value being placed on this vital process of community life. Further, in a growing number of communities, the organizations are describing how members participating in their programs have been adopting a more thoughtful approach to considering the advantages and disadvantages of various technological proposals.

In Uganda, for instance, a group of youth that was approached by a development organization promoting maize monoculture systems requiring high use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides asked the organization’s representative numerous questions about the long term economic and environmental implications of the system; in the end, the group decided not to adopt it and shared with their tutor that they will no longer blindly follow the popular systems of the region. Another group reached out to village leaders and mobilized the community to construct a borehole on a piece of land donated by a group participant, providing water to sustain their experimental plot; group members also agreed to work on each other’s plots to ensure that all had time to study. The organization implementing the PSA program in the country, Kimanya-Ngeyo Foundation for Science and Education, established a large agricultural research farm, organizing training seminars and reflection spaces for tutors and participants to share their experiences with their plots. They further guided the program’s tutors to work with former and current participants as well as community members to establish similar research plots in each region where the program is being implemented.

In Zambia, Inshindo Foundation carried out a campaign to promote backyard gardens in Kabwe, and 50 households adopted the practice. Follow-up efforts will examine how households’ production of food impacts their income and overall wellbeing. The agronomists of the Foundation are in a continuous dialogue with more than 500 farmers, many of whom have studied the agriculture units of the PSA program. The organization has recently launched a Center for Community Agriculture, where farmers from the community can study, consult, and experiment with different systems; the Center includes a local library, a seed bank, and a simple laboratory accessible to the community.

In Cameroon, several former and current participants of the PSA program offered by Emergence—a Baha’i-inspired agency in the country—established an association through which they undertake collective activities, including many in agriculture. In the eastern region, which has received a large number of refugees from Central African Republic, participants have entered into crop production and animal husbandry with the refugees to assist them in addressing their dietary and financial needs.

In the Central African Republic and Malawi, the plots established around Bahá’í-inspired community schools have centered on the nutritional needs of the children and have provided a laboratory for classrooms to study biological sciences. Further, many farms neighboring the schools have adopted the practices implemented on their learning plots.

While such stories abound on the African continent, given the complex and long-term nature of this sphere of endeavor, it would be premature to state that significant changes to production processes have resulted from these efforts. Nevertheless, an example from the south Kivu region of Democratic Republic of the Congo gives us a glimpse of a community that demonstrates the power of collective will to transform agricultural systems, grounded in spiritual principles and a systematic process of study, consultation, action, and reflection.

Reaching Thousands: Initial Insights from the Kivu Region, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Fondation Erfan-Connaissance, based in Bukavu, Democratic Republic of the Congo, has been offering its teacher-training program to promote the establishment of community schools in the Kivu region since 2007.

Following nine years of activity in the area of primary education, in 2016 the organization began to incorporate the two agriculture units of the PSA program in its teacher-training seminars, first offering them to its 31 facilitators and then to the 185 teachers whom they had been accompanying. The organization hoped that the study of the units would help in three areas: to build the scientific capacities of the teachers, to develop the capabilities needed to converse with families of their students about questions related to production and nutrition, and to improve their production systems and increase their income, especially in villages where teachers are also farmers. In schools with sufficient resources and capacity, DHE plots would be established to grow food for the students and serve as a learning space for both the students and the farming families in the community.

Soon after the first training seminar on the agriculture units, six schools established DHE plots, including one in the village of Canjavu in south Kivu—a number that has since multiplied. In the urban area of Goma in north Kivu, the teachers’ conversations with students and their families led to the establishment of around 80 backyard gardens. The influence of the training teachers received also led to other community agriculture initiatives, including a large seed bank project based in the Nshimbi village in south Kivu. Now, more than 1,000 individuals are engaged in some form with the DHE plots and backyard gardens and another 1,500 have been reached through seed distribution by the Nshimbi seed bank and dissemination of a number of technologies used in DHE plots among neighboring households, especially in Canjavu.

Backyard Gardens, Goma

The national primary curriculum of the Democratic Republic of the Congo contains basics of agricultural science. However, especially in urban areas where the value given to agriculture is increasingly lost and farming is viewed as the work of the uneducated, it was common for teachers of community schools to move quickly past lessons related to the topic. Following the initial training on the two PSA agriculture units in 2016, however, Fondation Erfan-Connaissance noticed a rise in appreciation for agriculture among the teachers in Goma and an increase in their engagement with students about the subject. Although it was difficult for most schools there to establish plots—Goma is a volcanic area and the size of land available to schools and households is very small—a few schools with sufficient resources were able to begin cultivating crops, from which the students learned about the process of plant growth.

As a result of conversations about production in and outside the classroom, a number of students approached their parents to ask whether they could plant some crops in their backyards. This effort was also supported by the teachers and program coordinators during their visits to the households. In most cases, the parents helped with obtaining the seeds, and the students began to take care of the crops. Within a period of around one year, some 80 backyard gardens had been established. The teachers regularly visited their students’ gardens and witnessed not only the rise in their capacity to manage their garden but also greater evidence of qualities such as patience, determination, and generosity.

Gradually, the coordinators of the teacher-training program in Goma began to observe changes in the nature of interactions between families in neighborhoods with backyard gardens. Households began to exchange planting materials and share experience and advice. In one neighborhood, six families began to collaborate very closely in their production activities, growing medicinal plants as well as food crops.

Further, as the work on gardens continued, the families were able to supplement their income by selling their produce in the local market. In response to the growing interest in urban farming, and to encourage more to engage in the process, two of the Bahá’í-inspired community schools established seed banks, and one began to provide seedlings to five other community schools as well as a number of teachers and community members. Agriculture became an essential topic of conversation during parent-teacher meetings at schools, and reflection meetings focusing specifically on production emerged with an average participation of 120 individuals.

Community Seed Bank, Nshimbi Village, South Kivu

The village of Nshimbi is a center of intense Bahá’í community building activity; there are approximately 250 residents who participate regularly in devotional meetings, 280 children who attend Bahá’í children’s classes, around 140 participants in the junior youth spiritual empowerment program, and about 90 engaged in study circles. To respond to the academic needs of the children, a Bahá’í-inspired community school was established in the village in 2016.

After receiving training on the two PSA units on agriculture, one of the teachers, accompanied by the agronomist of the Foundation, started a conversation with the village chief and community members about the need to diversify production systems and establish a local seed bank. The chief convened a meeting with the participation of over 500 individuals, and as a result of the consultation, the community decided to allocate two plots with a total area of approximately 12,000 square meters for the production of seeds and cuttings of a large variety of species. Further, each family was encouraged to establish a vegetable garden to diversify locally available products.

As these efforts gained momentum, the community approached a development organization promoting seed banks to help in the construction of a small building for the bank; the community contributed bricks, sand, and labor, while the organization donated cement and metal sheets. A structure of 35 square meters was thus constructed within a few weeks on a piece of land donated by the chief. In addition, the community put together an administrative arrangement to oversee the bank’s operations.

Among the 25 families that initially made up the bank’s membership, three committees were formed—a management committee to organize meetings and handle the bank’s records, a monitoring committee to distribute the seeds and help members of the community with aspects of cultivation so that they could meet their commitments to the bank, and an advisory committee, of which the village chief would be a member, to protect the initiative from moving in undesirable directions. Further, a number of solidarity groups emerged around the bank focusing on the sale of the agricultural products, on animal husbandry, and on adult literacy. The families would obtain a certain amount of seeds as a loan and would return it with an interest rate that differed from crop to crop; for maize, for instance, the farmer was to return 1.5 kilograms of seed for every kilogram borrowed. Within one year, the number of families who were members of this committee increased from 25 to 200, joining from eight neighboring communities.

In a recent reflection meeting, a mother commented that the seed bank was addressing the problem of malnutrition in the village, as families had been planting monoculture systems before its establishment, which limited the number of crops available for household consumption. It was also observed that the participation of women in community consultations has increased. Further, 60 of the 200 families have entered into animal husbandry from the profit they have made by diversifying their products.

Multiplication of DHE plots and secondary production, Canjavu village, South Kivu

The village of Canjavu is located around 45 minutes west of Bukavu, the capital of the South Kivu province. It has a population of approximately 3,900 divided into around 500 households. As of April 2020, a large percentage of the population in the village was engaged in more than 600 community-building activities inspired by the teachings of the Bahá’í Faith, including 468 devotional meetings, 40 Bahá’í children’s classes, 50 junior youth groups and 42 study circles. These activities assist the community members to develop their spiritual and intellectual capacities and provide social spaces for meaningful conversations. This has, in turn, led to a systematic process of study, consultation, action, and reflection over ways in which they can advance the various processes of community life, including education, health and agriculture.

The Bahá’í-inspired community school serving the village, Ecole Communautaire Muzusangabo, was established in 2011; currently 105 students attend kindergarten through grade 6. During 2016 and 2017, the school’s teachers as well as 45 farmers from the village and three nearby localities participated in training offered by Fondation Erfan-Connaissance. The training led to the establishment of a DHE plot connected to the school to meet the nutritional needs of the students and serve as a source of income for the school, as well as DHE systems on the farms of those participating in the study. In 2019, the participants decided to each accompany three households that had shown interest in establishing diverse systems on their own plots, leading to the establishment of around 100 DHE plots in the village. As a result, during the Covid-19 pandemic, one village resident stated:

During this health crisis, we are not afraid of running out of food because while we are planting, we are also enjoying the harvest of our previous cultivation. In addition, with the closure of schools, our junior youth… prepare their small plots to help their families. They cultivate amaranth whose leaves are excellent for health.14https://www.bahairdc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=154:la-crise-sanitaire-une-source-d-unite-spirituelle-pour-le-quartier-cpa-lubobo-2&catid=137&Itemid=571

Technical assistance from a local Bahá’í-inspired organization allowed the community to expand the scope of its production activities. In addition to food crops addressing dietary needs, they began to cultivate beetroots as a cash crop in order to produce and sell juice. The funds generated from the sale enabled them to purchase school supplies and to address other community needs. They obtained blenders to simplify the juice-making process and a basic milling machine to grind their own flour, producing donuts that have become popular in neighboring towns and villages.

Beyond the increased capacity of the community to engage in collective income-generating projects, a notable outcome of the action-research process has been a rise in the farmers’ scientific and technological capacities.15They have experimented with the effect of Tithonia on production, comparing untreated and treated sections of land, concluding that fertilizers and pesticides made from the plant have notably increased yields. They questioned assumptions regarding which crops grew well in the region and experimented with planting a number of them, including onions that provided a good harvest. They showed determination when the school plot did not produce well one year, questioning the causes and identifying the plot’s distance from the school to be a significant factor preventing regular monitoring; they have since relocated the research plot, which resulted in increased production. The spiritual qualities and the scientific capacities developed by the group, and the resulting rise in their production, have attracted the interest of other households in the village. While DHE systems are running in 100 households, almost all 500 households participate in the village reflection meetings on agriculture, encouraged by the chief.

The story of Canjavu has been spreading within the region. They have received students from nearby universities who wish to learn about their systems, and a member of the community actively engaged in the plot was asked by the representative of a regional agricultural cooperative to visit different communities with her and share the group’s experience and learning. The director of the Bahá’í-inspired school in the village has commented:

The spirit of unity in the village of Canjavu attracts neighboring villages which also want to learn. People see how present evils are overwhelming humanity. They feel that it is time to join any human enterprise that seeks to act in the Light of Unity!16 https://www.bahairdc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=154:la-crise-sanitaire-une-source-d-unite-spirituelle-pour-le-quartier-cpa-lubobo-2&catid=137&Itemid=571

Future Prospects

At the time of writing this article, humanity is experiencing a worldwide pandemic that has not only already caused the loss of hundreds of thousands of souls but has put the livelihoods of millions more into great jeopardy. Africa has not been immune, and the prospect of famines continues to threaten the continent as it does the rest of the world. Restrictions on movement that have reduced the exchange of products between regions and countries have made it ever-more urgent for each and every community to think deeply about the question of food, and communities are questioning the path that has led them towards dependency.

“Be anxiously concerned with the needs of the age ye live in,” are the words of Bahá’u’lláh, “and center your deliberations on its exigencies and requirements”17Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, no. CVI. “For all beings are linked together like a chain;” says Abdu’l-Bahá, “and mutual aid, assistance, and interaction are among their intrinsic properties and are the cause of their formation, development, and growth.”18Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions, no. 46 Can neighborhoods and villages be assisted to consult prayerfully together to determine ways in which they can produce and market their staple foods in collaboration with each other? What would it take for each household in cities and villages to grow food with whatever resources are available to them? Can current systems focusing entirely on cash crops for export be transformed into systems that would also meet the nutritional needs of thousands of a country’s residents? Can the youth of each community, many of whom have thus far chosen to move away from agriculture and rural areas, seeking the promise of a better life in overcrowded urban settings—a promise that very often leads to disappointment—be encouraged and assisted to channel their energies and focus towards advancing agriculture? How can efforts build on the spirit of service that is characterizing an increasing number of communities that have been in touch with the Creative Word? These are the types of questions that are currently being explored by Bahá’í-inspired organizations engaged in agriculture in Africa as they recall the words of Abdu’l-Bahá that the “fundamental basis of the community is agriculture… All must be producers”.

During the past two years, the global Bahá’í community has witnessed the dedication of the first two local Bahá’í Houses of Worship in the world—the first in Battambang, Cambodia, on 21 September 2017, and the second in Norte del Cauca, Colombia, on 22 July 2018. Thousands gathered in each location to celebrate the completion of these temples, signalling the emergence of an institution that will one day be constructed in every village and town in every country.

The House of Worship is the central edifice of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár (the Dawning-place of the Praise of God), a new development inaugurated by Bahá’u’lláh and described by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as one of the most vital institutions in the world.

In addition to a temple welcoming people of all faiths, races, and ages to share in prayer and meditation, unencumbered by ritual, the temple complex will eventually include service-oriented dependencies dedicated to social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific pursuits.

Eight continental Bahá’í Houses of Worship have been constructed as Mother Temples

for Africa, the Indian subcontinent, North, Central, and South America, Europe, Australia, and the Pacific. The announcement in 2012 of plans to build local Houses of Worship in Battambang, Norte del Cauca and three other areas, as well as the first two national Bahá’í temples, was extraordinary in a number of ways. One is that in a rapidly urbanizing world—city people outnumbered rural people for the first time in 2007—the first local and national temples will be constructed in countries with largely rural populations. The first two national temples will be built in Papua New Guinea (87% rural) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (57%). The local temples are planned for Cambodia (79%); Matunda-Soy in Kenya (74%); Tanna in Vanuatu (74%); and Bihar Sharif in India (67%). Colombia, with a majority urban population, is the exception, but Norte del Cauca is a largely rural region.

Siting the local Houses of Worship in these areas is by no means random. In each case, the spirit of worship and service integral to the institution is already evident: each community hosts multiple devotional gatherings open to all, and large numbers of children, youth, and adults are engaged in an educational process that builds capacity for service to humanity. Thus, the House of Worship is a physical manifestation of a spiritual reality already present in these rural communities.

In 1891, in one of His most important writings, the Tablet of Carmel, the founder of the Bahá’í Faith, Bahá’u’lláh, expressed His longing to announce to every spot on the surface of the earth

the glad tidings of His Revelation. Since then, His followers have made consistent efforts to take the Bahá’í teachings to all peoples, including those in the most remote rural areas. It has often been found that rural people are drawn to the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh in large numbers and have been among the first to respond to their transformative influence and to put them into practice.

Why Rural?

The Bahá’í Faith was the first major religion to emerge in the modern period. Although the 19th and 20th centuries are characterized by non-agricultural industrialization and urbanization, the Bahá’í teachings on social and economic issues placed great importance on agriculture, farmers, and village life.

In the Tablet of the World, also revealed in 1891, Bahá’u’lláh outlined that which is conducive to the advancement of mankind and to the reconstruction of the world.

1Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitab-i-Aqdas, 89–90. He identified several principles that would contribute to achieving social order, including international cooperation and disarmament; a new ethos of universal fellowship, epitomized by the adoption of a common auxiliary language; the training and education of children; and agricultural development. Bahá’u’lláh stated that special regard must be paid to agriculture,

as unquestionably

it precedes the other principles in importance. Perhaps this is why Bahá’u’lláh also stated that agricultural work is identical with worship.

In keeping with this principle, Bahá’u’lláh’s son, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, who led the Bahá’í community after His Father’s passing in 1892, later stated that the fundamental basis of community is agriculture,

that the peasant class and the agricultural class exceed other classes in the importance of their service,

and that the farmer is the primary factor in the body politic.

Given the importance placed on agriculture, attention to the needs and aspirations of rural populations has been a priority going back to the early history of the Bahá’í Faith, when Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá showered their love on farmers and villagers, offered them tangible support, and contributed significantly to the discourse on rural development.

While religions have always had an association with agriculture, the Bahá’í teachings on this topic are considerably more elaborate than those of most previous faiths. Why would the Founder of the first modern religion place so much emphasis on agriculture?

In the time of Bahá’u’lláh, farmers comprised the vast majority of the world’s population. In 1875, 91% of the global population lived in rural areas, but a major shift was already underway: in 1800, 5% of the population was urban; by 1900, the urban share of population grew 2.6 times, to 13.3%. In industrializing areas such as Europe, the shift was more dramatic, from 7.3% urban in 1800 to 26.1% in 1900. Citification was picking up steam: humanity was 30% urban by 1950, 50% urban for the first time in 2007, and is 55% urban today. By 2050, a 66% urbanized population is projected.

We are migrating to cities en masse; however, 3.4 billion people still live in rural areas. And the statistics obscure the nature of urbanization: Close to half of the world’s urban population lives in towns and small cities. Many of these towns retain strong rural connections and are populated by people connected to agriculture.

While places like North America now have a tiny farm population living on large mechanized farms, throughout much of the world, especially Asia and Africa, smallholders produce most of the food on farms averaging one to two hectares in size.

There are some 500 million farms worldwide, 200 million pastoralists, and an estimated 450 million farm laborers, many working in the plantation sector. In addition, large numbers of casual and temporary workers are engaged by small and large growers. Roughly one third of humanity, some 2.5 billion farmers and their families, derive their livelihoods from agriculture; thus, farmers remain the largest single occupational group. Rural people also work in forestry and fisheries. The International Labour Organization reports that as many as 1.75 billion people derive at least some of their subsistence or income from forests, including 60 million Indigenous people who depend on natural forests for their livelihoods. Another 58 million people are engaged in fisheries and aquaculture. It should also be noted that as many as 800 million people are involved in urban and peri-urban food production.

Today, we speak of the consumer

or information

or post-industrial

economy, giving the impression that the global economic order is decoupling from traditional resources extracted from the hinterlands. In fact, the consumption of practically every renewable and non-renewable resource is rising. Agricultural ecosystems cover nearly 40% of the terrestrial surface of the Earth. Human beings, one of an estimated 8.7 million species that cohabit the planet, now use 20% of Earth’s Net Primary Production (the total plant material produced) on land. Consequently, rural producers remain critically important players in the global economy.

Urban and rural populations are mutually dependent. In fact, as the number of rural producers decreases as a portion of the total population, their relative importance increases. Rural people are largely responsible for meeting the rapidly expanding urban demand for food, including fish, natural fibres, and forest products. Importantly, they are also increasingly important as providers of a wide range of essential ecological services associated with the management of soil, watersheds, forests, and fisheries.

Despite their essential services to society, the situation of rural people is often precarious. The historian Eric Hobsbaum points out, for instance, the anomaly that on the whole, the countries with the highest percentage of agricultural population are the ones which have difficulties in feeding themselves, while the world’s food surpluses come, on the whole, from a relatively tiny population in a few advanced countries.

2Eric Hobsbawm, On History (New York: The New Press, 1998), 157.

A vast majority of the global poor live in rural areas—half in Sub-Saharan Africa—and more than half are under 18 years of age. The hunger that these people experience is a consequence of poverty, and while the causes of poverty are complex, they are often associated with power dynamics that marginalize rural people.

Fortunately, the number of people living in extreme poverty has declined over the past several decades. According to the most recent World Bank estimates, while about 35% of people lived below the extreme poverty income threshold of $1.90 a day in 1990, adjusted for inflation, that number is closer to 11% today. While this is a positive trend, rural poverty remains deeply entrenched and the situation of the rural poor remains tenuous. Simply moving above the threshold of $1.90, to $1.91 or to $2 or $3 a day in income does not solve the problem. The World Health Organization has reported that global hunger, which has tended downward along with extreme poverty, is rising again. In 2016, 815 million people, more than one in ten people, were chronically hungry.

For those who have been able to move out of poverty, progress is often temporary: economic shocks, food insecurity, and climate change threaten to rob them of hard-won gains. It becomes increasingly difficult to assist those remaining in extreme poverty, according to the World Bank, especially those in fragile contexts and remote areas. Access to good schools, healthcare, electricity, safe water, and other critical services remains elusive for many people, often determined by socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity, geography, politics, and, increasingly, environmental and climate factors. We see, for instance, the recent dramatic rise in the number of social and environmental refugees—some 65 million people cut off from their communities and families, willing to risk their lives to find a more secure life.

All this points to the continued relevance of the Bahá’í teachings on agriculture and the importance of supporting rural people in their efforts to achieve a better life and to contribute to the just and sustainable world order envisioned by Bahá’u’lláh. Perhaps this is why ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, in his extensive discourse on the reorganization of society, stated that the transformation of economic systems must commence with the farmer and then be extended to the other classes.

3From a tablet dated 4 October 1912 to an individual believer, included in Economics, Agriculture, and Related Subjects by Bahá’u’lláh, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and the Universal House of Justice, compiled by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, in Compilation of Compilations, vol. 3 (2000): 5–17. He said that the solution to the economic problem begins with the village, and when the village is reconstructed, then the cities will be also.

4The Baha’i World 4: 450.

Commence with the Farmer: Bahá’í Principles for Rural Development

What are the Bahá’í teachings on rural life and agriculture? Since they are extensive, and there is insufficient space to go into detail here, four main themes will be summarized.

Centrality

As mentioned, Bahá’u’lláh stated that agriculture should be considered first among the fundamental principles for the administration of human affairs. While agriculture and rural populations have in many ways been marginalized in the modern world, the fact remains that civilization is entirely dependent on farmers. Both agriculture and non-agricultural industry are needed to support civilization, but in the final analysis, agriculture is primary and other industry secondary.

Agriculture (which includes forestry and fisheries) is fundamentally different from other economic activities in that agriculture’s products result from life processes and its means of production are living systems. Beyond providing food and other products, as well as incomes, agricultural activities provide key ecological services and have a global impact, including an impact on climate. This is why no sustainable human future can be conceived unless and until the centrality of agriculture is recognized.

Corollary to this is a farmers first

approach, in which agricultural development is focused around the requirements and concerns of farmers and farm laborers, especially those who are impoverished. Currently, the agrifood system is built around the needs of consumers rather than producers. Similarly, we concern ourselves with cities and neglect the village and countryside. Instead, efforts must be made to prioritize and strengthen agriculture, starting at the farm and village level with the needs of rural people foremost.

Raising the centrality of agriculture to the level of spiritual principle is key to ensuring that adequate attention and resources are given to its proper development.

Prosperity

Bahá’u’lláh’s vision for the future is one in which everyone will enjoy the benefits of civilization. Wealth is most commendable,

said ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, provided the entire population is wealthy.

5‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Secret of Divine Civilization, 24. The pivotal Bahá’í principle of the oneness of humanity implies that a minimum standard of well-being is an inalienable human right.

Every human being has the right to live; they have a right to rest, and to a certain amount of well-being,

said ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The arrangements of the circumstances of the people must be such that poverty shall disappear, and that every one as far as possible, according to his position and rank, shall be comfortable. Whilst the nobles and others in high rank are in easy circumstances, the poor also should be able to get their daily food and not be brought to the extremities of hunger.

6‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 134; ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London, 29.

Today this principle is widely recognized as the Right to Food. The realization of the right to adequate food is not merely a promise to be met through charity,

according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. It is a human right of every woman, man and child that is to be fulfilled through appropriate actions by governments and non-state actors. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development prioritizes scaled up, transformational action to eradicate poverty and end hunger and all forms of malnutrition, recognizing that permanent eradication of hunger and the realization of the right to adequate food for all are achievable goals.7Website of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, www.fao.org/right-to-food/en/.

Establishing equitable and effective means to redistribute wealth is a necessary element in the redesign of the food and agriculture system to ensure an adequate supply of food and access to food producing resources. Oxfam reports that in one recent 12-month period, the wealth of the world’s billionaires increased by $762 billion, an amount sufficient to end extreme poverty seven times over.8Reward Work, Not Wealth, Oxfam Briefing Paper, January 2018, https://www.oxfam.de/system/files/bericht_englisch_-_reward_work_not_wealth.pdf Eliminating extreme poverty necessitates the elimination of extreme accumulation of wealth in the hands of a tiny elite. Overcoming such imbalances will involve more than policy change. It is also a moral issue.

The Bahá’í teachings offer a number of spiritual principles and practical measures designed to redistribute wealth and eliminate poverty. Bahá’u’lláh frequently admonished the wealthy and powerful to give generously to the poor on a voluntary basis. The Bahá’í teachings also call for policies such as progressive taxation, limits to wealth accumulation and monopolies, fair wages, profit sharing, and moderate interest on loans. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also proposed a local institution he described as the village storehouse

which would administer and regulate the economic affairs of the village to ensure that all members of the community are protected.

One of the most significant measures Bahá’u’lláh created to eliminate extremes of wealth and poverty is a law known as Huqúqu’lláh (Right of God). According to this law, 19% of net wealth is given to the Universal House of Justice, the international governing body of the Bahá’í world community. This law is now being put into effect in the worldwide Bahá’í community. As the Bahá’í community grows, this fund will become substantial and will ultimately be used to assist the poor and for other philanthropic purposes.

Another important principle is the understanding that material wealth is not an end in itself. Bahá’u’lláh urged His followers to moderate their wants, with the understanding that material wealth is a means to support people in their pursuit of spiritual development. This involves a new understanding of prosperity in which wealth can be seen in terms of health, positive relationships, meaning, and the capacity to serve.

Sustainability

According to Bahá’u’lláh, All men have been created to carry forward an ever-advancing civilization.

9Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, 215. The term ever-advancing

implies that the process of human development must progress from one generation to the next. Consequently, to fulfill the purpose of our creation, the processes of civilization must be sustainable and our ability to manage natural systems must be informed by the fact that civilization ultimately depends on their long-term viability.

Bahá’u’lláh’s statement raises sustainable development to the status of a spiritual principle that is central to the purpose of our existence. Since agriculture is fundamental to civilization, a sustainable food and agriculture system is intrinsic to the world order prescribed by Bahá’u’lláh. Future agricultural systems will benefit from a profound understanding of the responsibilities of our species to maintain the equilibrium of the ecosphere. In this regard, the Bahá’í teachings describe a new conception of the relationship between humankind and the natural world, in which the ecosphere is conceived as the extended human body.10See Paul Hanley, The Spirit of Agriculture (Oxford: George Ronald, 2005), 51–55.

A number of specific principles found in the Bahá’í writings support the sustainable development of agriculture.

Capacity

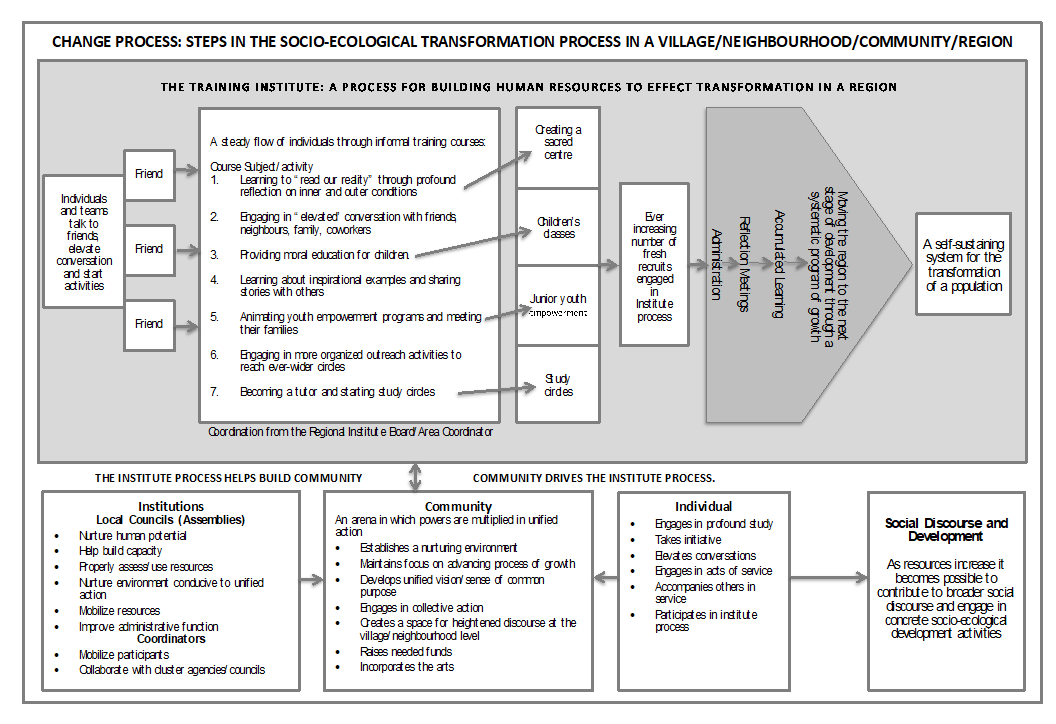

The Bahá’í teachings can be seen as a roadmap for a methodology to build capacity in individuals, communities, and institutions to achieve the above objectives. Building capacity is a primary goal of the Bahá’í community throughout the world at this stage of its development. The chief means of doing this is a grassroots educational system that both emerges from and fosters a process of community development. This process was first used in rural Colombia starting in the 1970s and is now taking root in thousands of Bahá’í communities around the world.

The training institute is a participatory public educational process that aims to build foresight, wisdom, and a capacity for moral choices that favor collective well-being over self-interest. It is coordinated and focused, while also being inclusive and open to diverse approaches. Moral capacity is being developed at the village and neighborhood level among a growing cohort of people who begin to build service-oriented communities capable of reading and responding to current realities. This approach has been particularly successful in rural areas, where the institute has contributed to the empowerment of children, youth, women, and men.

The processes of community development also enhance the spiritual life of the community and advance the moral and material education of children and youth. In many ways, this approach can be seen as the embryonic form of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár, the institutional complex that combines worship and service in every community. And as mentioned, the new local temples are taking shape in communities where an advanced process of growth involving the training institute is in place.

The diagram below shows the elements of a village transformation process based on the training institute and a set of core activities pursued in Bahá’í communities. Building capacity ultimately leads to the ability to engage in effective public discourse, which in turn facilitates social action. In the case of the village, this capacity can be directed to analyzing and solving the problems faced by farm families.

Begin with the village

The Bahá’í teachings offer a theoretical approach to rural development, but this approach is not a formula. It is meant to be tested in the real world and adapted according to local conditions.

From the early days of the Bahá’í revelation, Bahá’í communities in rural areas have striven to uplift themselves materially and spiritually through a wide range of initiatives in different contexts and fields. It must be emphasized, however, that Bahá’í communities around the world are still at the very early stages of learning about the question of village prosperity.

As they move forward into this area of experimentation and learning, they can look to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s activities in the field of rural reconstruction for an extraordinary example of the application of Bahá’í principles to rural development. It is instructive, then, to consider in some depth how He applied these development processes and to reflect on their current relevance.

Among His innumerable labors as head of an emerging world religion, including His extensive writings and communications (an estimated 30,000 tablets), international travel to spread the Faith, and administering to the daily needs of the poor of His own community, Akká, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá found time to put into practice many of the Bahá’í principles of rural development in a village about 100 kilometers from His home.

In 1901, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá purchased the lands of ‘Adasiyyah as a whole village estate, paying 400 Turkish gold lira. The village is situated southeast of the Sea of Galilee and south of the River Yarmuk at the north end of the Jordan River, very close to the current border between Israel and Jordan. The original area purchased was 920 hectares; however, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá immediately gave away 230 hectares, leaving a total of 690 hectares.11The description of the ‘Adasiyyah project is a summary based on I. Poostchi, ‘Adasiyyah: A Study in Agriculture and Rural Development, Bahá’í Studies Review 16 (2010): 61–105. doi: 10.1386/bsr.16 61/7.

The village was developed in several phases. At first, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá made arrangements for several farmers to begin the work, but they found it very difficult due to the poor condition of the land and the heavy labor required. What is more, they were subject to raids by thieves who stole whatever meager crops they were able to produce. In 1907, recognizing these obstacles, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá contacted the Bahá’ís in Persia and asked them to send experienced farmers to settle in ‘Adasiyyah.

Over the next couple of years a group of farmers from around Yazd began to arrive and commenced farm operations. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá informed these farmers that they were coming to one of the most inhospitable places on Earth. In the Jordan Valley, the heat is stifling from June to September, with an average daily temperature around 38°C. Malaria was a significant problem. While the land had once been fertile and supported a large population, agriculture in the region had fallen into decline under Ottoman rule. A great deal of effort would be required to prepare the land, which was overgrown with scrub bush, much of it thorny. However, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had told them that God would gradually make the climate of ‘Adasiyyah more comfortable, merely for the sake of the Bahá’í farmers from Iran!

These farmers would overcome many obstacles to implement the project planned and directed by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. At first, hand labor with simple tools was used to prepare the land, but gradually draft animals and plows were added. They also had to build homes to provide for the basic needs of their families, and these and other buildings were initially made from mud brick.

Before the farmers started cultivation, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá instructed them to meet, consult, and then divide the land among themselves. Every farmer was to take charge of a certain area of farmland in proportion to the size of his family. The average allotment was based on units of 2.5–3 hectares, plus 3–6 hectares to grow food for their family and fodder for their livestock.

Precipitation was sufficient to support rain-fed grain production and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá recommended that the farmers begin by planting wheat and barley. Often the farmers visited Haifa or Akká to seek ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s advice. He would make a specific recommendation for that season, assuring them of a bumper harvest and great bounty. At times, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would form a partnership with a specific farmer for a certain crop, sharing expenses. These partnerships would often result in extremely high yields.

An important characteristic of the Jordan Valley is a year-round growing season, making double cropping feasible. Over time, the farmers were able to become quite productive and to produce surplus grain. Although some raiding continued to occur, security was improved by building bonds of friendship in the wider community, an activity ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had insisted on.

During the First World War, when drought conditions added to the disruption caused by the fighting, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá foresaw famine. He went to the farmers in ‘Adasiyyah and asked them to empty their granaries, excepting the amounts needed for their own use and for reseeding. He also asked them to purchase grain from farmers in the area. A train of 200 camels was dispatched to Haifa and Akká, where the grain was distributed among the local population, preventing starvation. This humanitarian effort resulted in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá being knighted by the British, who had gained control of Palestine during the war. He accepted the honor as the gift of a ‘just king’ but never used the title.

The farmers’ initial success opened new horizons. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged them to diversify their crops, and as early as 1910, they expanded into vegetable production for their families and for the market. In the beginning most farmers grew eggplant, which is easy to grow, requires little cultivation, has few pests, and produces an abundant crop. It is said the Bahá’í farmers were the first to introduce eggplant to the northwest of Jordan, Palestine, and the Golan Heights. Soon, wheat, barley, chickpeas, lentils, and broad beans were produced side by side with a wide variety of vegetables.

Next, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged the farmers to add fruit trees. He specifically instructed them to grow table grapes, oranges, lemons, tangerines, grapefruits, and limes. Fruit crops were more productive and fetched much higher prices than other farm products, especially the large yellow lemons and sesame seeds. It was customary to plant broad beans between and around pomegranate trees. Some were used fresh or dried for human consumption, but a large part of the crop was plowed into the soil while still green to improve soil texture and fertility.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá also introduced bananas to the region. During the last years of His life He received seven suckers from India. Without having ever grown bananas, He guided the farmers in ‘Adasiyyah in planting and caring for the new crop. He instructed the farmers to use the basin system of planting instead of the row system commonly used in other countries. The soil around a number of closely spaced trees was ridged up to form a small rectangular basin. The main advantage of the basin was that it held irrigation water for a longer time and allowed a gradual and slow infiltration of water into the soil.

Until that time no one in the region knew anything about this crop, let alone how to grow it. At first, the villagers were even unsure how to eat it, finding it quite unpalatable and hard to swallow—until they were shown that the outer skin must be removed. Within a few years many farmers in the region were growing bananas and profited greatly from this relatively lucrative business.

Gradually, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s prediction of improving conditions came true. In the early years, malaria was rampant. Some of the Bahá’ís developed the disease and even succumbed to it. To address the problem, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá instructed the community to plant a certain type of eucalyptus around the lagoon in the middle of ‘Adasiyyah. This variety produces quinine in its leaves and branches, which acts as a deterrent to the malaria parasite. The trees grew quickly, sucking up large quantities of the mosquito-infested water. Gradually the incidence of malaria declined and disappeared. The trees also had a cooling effect on the surrounding area. An added benefit was the lumber, which was purchased by builders for use in ceiling trusses.

Along with the diversification of crops, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged additional methods to improve the productivity and sustainability of the farms, such as crop rotation. The normal rotation practiced by the farmers in ‘Adasiyyah for rain-fed crops was a succession of wheat, lentils, barley, chickpeas, vetch, and white maize. Clover and alfalfa were also included in rotations, and as green manure plow downs. Since the farmers used an intensive system of crop production, fields were rarely left fallow.

In addition to the use of nitrogen-fixing legumes in rotation, manure was added to increase the yields of crops. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged the friends in ‘Adasiyyah to diversify into livestock, and in due course every farm household reared cattle, sheep, goats, poultry, and pigeons, which, in addition to meat, milk, and eggs, produced the required amounts of manure. Pastoralists who lived in the vicinity also sold manure to the farmers of ‘Adasiyyah.

The Bahá’í farmers were almost self-sufficient, in terms of their own food needs. However, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá advised them to increase their income by selling products in markets beyond the immediate boundaries of Jordan. When the Bahá’í farmers sold their products in Akká, Tiberias, Haifa, or Damascus, they purchased some of their needs from the markets in these towns. This approach contributed to the regional economy.