‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ’S READING OF SOCIAL REALITY

‘Abdu’l-Bahá is a figure unique in religious history. Understanding His critical role is essential to understanding the workings of the Bahá’í Faith – in its past, present, and future.

For forty years ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was a prisoner of the Ottoman Empire, having been exiled as a nine-year-old child, when members of Bahá’u’lláh’s family were expelled from Iran to the Ottoman domains. Undeterred by the restrictions to His freedom and the challenges of daily life, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá directed His attention to administering the affairs of the growing Bahá’í community and to easing the plight of humanity by actively promoting a vision of a just, united, and peaceful world.

Keenly aware of the events transpiring in the world at large, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá viewed the establishment of universal peace as one of the most critical issues of the day. His writings and public talks outline the Bahá’í approach to peace and methods for its attainment and explain and illuminate the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh. They reflect a profound and sensitive understanding of the state of the world and demonstrate the relevance of the Bahá’í teachings to the alleviation of the human condition. The Bahá’í approach stresses a reliance on the constructive power of religion and on the forces of social and spiritual cohesion as a way to impact the world.1For a detailed discussion of the Bahá’í teachings on peace, see Hoda Mahmoudi and Janet A. Khan. A World Without War: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the Discourse for Global Peace (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing, 2020).

‘Abdu’l-Bahá saw in World War I a harrowing lesson of the human necessity for peace – and of the darkness that can ensue without peace. He knew and wrote extensively that nothing short of the establishment of the spiritual foundations for peace could result in lasting peace and security for humanity. In His written works, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá repeatedly draws our attention to the need for establishing the spiritual prerequisites for peace, requisites which, in turn, remove the barriers to peace, such as racial prejudice, sexism, economic inequalities, sectarianism, and nationalism.

That remarkable time in the history of the world provides the backdrop to the Tablets of the Divine Plan, a series of letters ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed to the Bahá’ís of North America. A study of these letters together with two detailed letters2Tablets to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/188605710 on peace addressed to the Executive Committee of the Central Organization for a Durable Peace at The Hague provides an opportunity to better understand the nature of universal peace as envisioned in the Bahá’í writings, the prerequisites of peace, and how peace can be waged. The Tablets of the Divine Plan set out a systematic strategy aimed at strengthening embryonic Bahá’í communities, founded on the principle of the oneness of humankind, and mobilizing their members to engage in activities associated with spreading the values of peace. The Tablets to The Hague are examples from among ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s tireless efforts to contribute to the most relevant discourses of His time and to engage like-minded individuals and groups throughout the world in the pursuit of peace.3Mahmoudi and Khan, World Without War.

A POWER OF IMPLEMENTATION

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s caveat that “the power of thought” depends on “its manifestation in action,”4‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Paris Talks. Available at www.bahai.org/r/361617663 is particularly relevant to the idea of peace. Consider! Nearly 20 million men, women and children were killed during the four years of World War I!

‘Abdu’l-Bahá took the principles of global peace revealed by Bahá’u’lláh and shaped them into a practical grand strategy for how to understand, practice, and pursue peace. Among the voluminous writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the fourteen letters of the Tablets of the Divine Plan outlined detailed instructions and systematic actions for the spread of the spiritual teachings of the Bahá’í Faith throughout the world. Their aim was the establishment of growing communities throughout the world that would embody the values of peace, would comprise the diverse populations of the human family, and would contribute to the spiritualization of the planet—a vision that was being promoted as the world was witnessing the horrors and sufferings of the war:

Black darkness is enshrouding all regions… all countries are burning with the flame of dissension…the fire of war and carnage is blazing throughout the East and the West. Blood is flowing, corpses bestrew the ground, and severed heads are fallen on the dust of the battlefield.5‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/713519310

‘Abdu’l-Bahá called on the recipients of the Tablets to arise and take action, establishing throughout the planet new communities founded on the spiritual principles of love, goodwill, and cooperation among humankind. Through such calls for acts of sacrificial service that arising to spread the divine teachings would entail, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was promoting an antidote to the social and spiritual illnesses that contribute to the conditions of war. He reminded the recipients of His letters of the power of spiritual forces to transform hatred, division, war, and destruction into love, unity, dignity, and the nobility of every human being. “Extinguish this fire,” He wrote, “so that these dense clouds which obscure the horizon may be scattered, the Sun of Reality shine forth with the rays of conciliation, this intense gloom be dispelled and the resplendent light of peace shed its radiance upon all countries.”6‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/577240123

‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained that if we desire peace in the world, we must begin by planting peace in our own hearts. This principle can be found throughout the writings of Bahá’u’lláh:

What is preferable in the sight of God is that the cities of men’s hearts, which are ruled by the hosts of self and passion, should be subdued by the sword of utterance, of wisdom and of understanding. Thus, whoso seeketh to assist God must, before all else, conquer, with the sword of inner meaning and explanation, the city of his own heart and guard it from the remembrance of all save God, and only then set out to subdue the cities of the hearts of others. 7Bahá’u’lláh. The Summons of the Lord of Hosts. Available at www.bahai.org/r/581531547

While ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sought to mobilize the Bahá’ís of North America to spread the unifying message of Bahá’u’lláh throughout the world, He also pursued numerous opportunities to introduce into the discourses of His time essential concepts and principles that would help the thinking of His contemporaries to evolve and assist humanity to move towards the realization of peace.

Indeed, in His letters to the Central Organization for a Durable Peace, written in 1919 and 1920 after the war’s conclusion, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gently but unequivocally challenged His audience to broaden its conception of peace. Specifically, in His first letter, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explored “many teachings which supplemented and supported that of universal peace,” such as the “independent investigation of reality,” “the oneness of the world of humanity,” and “the equality of women and men.” Some other related teachings of Bahá’u’lláh that were explained by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá included the following: “that religion must be the cause of fellowship and love,” “that religion must be in conformity with science and reason,” “that religious, racial, political, economic and patriotic prejudices destroy the edifice of humanity,” and “that although material civilization is one of the means for the progress of the world of mankind, yet until it becomes combined with Divine civilization, the desired result, which is the felicity of mankind, will not be attained.”8‘Abdu’l-Bahá. First Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/551373700 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá then reiterated His point, stating:

These manifold principles, which constitute the greatest basis for the felicity of mankind and are of the bounties of the Merciful, must be added to the matter of universal peace and combined with it, so that results may accrue. 9‘Abdu’l-Bahá. First Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/376814060

In the Second Tablet to the Hague, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá observed that for peace to be realized in the world, it would not be enough that people were simply informed about the horrors of war. “Today the benefits of universal peace are recognized amongst the people, and likewise the harmful effects of war are clear and manifest to all,” wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

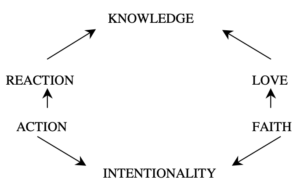

But in this matter, knowledge alone is far from sufficient: A power of implementation is needed to establish it throughout the world.… It is our firm belief that the power of implementation in this great endeavour is the penetrating influence of the Word of God and the confirmations of the Holy Spirit.10‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Second Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/705335105

Abdu’l-Bahá asserted that it is through this power of implementation that “the compelling power of conscience can be awakened, so that this lofty ideal may be translated from the realm of thought into that of reality.” “It is clear and evident,” He explained, “that the execution of this mighty endeavour is impossible through ordinary human feelings but requireth the powerful sentiments of the heart to transform its potential into reality.” 11‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Second Tablet to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/705335105

SPIRITUAL FOUNDATIONS OF PEACE

Understanding ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approach to peace also demands we understand Bahá’u’lláh’s direct engagement with the world and His doctrinal declarations concerning the Bahá’í Faith. Bahá’u’lláh’s writings describe a “progressive revelation” of religion in which individual religions arise to meet the need of their times. Bahá’u’lláh stated that particular religions were entrusted with a message and a spirit that “best meet the requirements of the age in which” that religion appeared.12Bahá’u’lláh. Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. Available at www.bahai.org/r/757983498 In this context, religions are viewed as the gradual unfolding of one religion that is being renewed from age to age. The variations in the teachings of these religions are attributable to a world that is constantly changing and needing spiritual renewal and spiritual principles. Because “ancient laws and archaic ethical systems will not meet the requirements of modern conditions,” then, as a new religion takes shape, new sets of laws and principles are revealed to humanity and new spiritual beliefs must always emerge.13‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/841894042

Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation calls on individuals to internalize spiritual principles and express them through actions. He proclaimed “to the world the solidarity of nations and the oneness of humankind.”14‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Available at www.bahai.org/r/955162073 He described “a human race conscious of its own oneness.”15Bahá’í International Community, Who is Writing the Future? (New York: Office of Public Information, 1999), V.2. Complex concepts such as human oneness and the global order were transformed from utopian ideals to spiritual commands of the highest order; the Bahá’í writings unfold and clarify how such commands might be fulfilled. Bahá’u’lláh’s vision also details the need for the construction of a World Order, an order comprising administrative institutions at the local, regional, national, and international levels. Such institutions, among other things, serve as channels for the application of spiritual principles. As the institutions evolve over decades and centuries, a new world order will eventually produce the conditions conducive to global peace. Yet, even as the Bahá’í writings envision a long-term process of global transformation and maturation of the human race, they also assert that change will also arise from individual and collective efforts at the grassroots of society. In exploring the creative Word and learning to apply it to their individual and collective lives, individuals are spiritually transformed from the inside-out, and they contribute to the transformation of communities, institutions, and society at large.

In describing the Bahá’í Faith’s strong prohibition on waging war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, stated that Bahá’u’lláh “abrogated contention and conflict, and even rejected undue insistence. He exhorted us instead to ‘consort with the followers of all religions in a spirit of friendliness and fellowship.’ He ordained that we be loving friends and well-wishers of all peoples and religions and enjoined upon us to demonstrate the highest virtues in our dealings with the kindreds of the earth….What a heavy burden was all that enmity and rancour, all that recourse to sword and spear!” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote of the impact of war on humanity. “Conversely, what joy, what gladness is imparted by loving-kindness!”16‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Light of the World. Available at www.bahai.org/r/408465671

‘Abdu’l-Bahá viewed peace as a central facet of the work of the Bahá’í Faith. There was no separating peace from the Bahá’í Faith, nor was there any separation between the Faith and peace. Peace was both medium and message, and the Bahá’í Faith itself was the vehicle for establishing peace. He explained, in His Second Tablet to the Hague, that the followers of Bahá’u’lláh were actively engaged in the establishment of peace, because their

desire for peace is not derived merely from the intellect: It is a matter of religious belief and one of the eternal foundations of the Faith of God. That is why we strive with all our might and, forsaking our own advantage, rest, and comfort, forgo the pursuit of our own affairs; devote ourselves to the mighty cause of peace; and consider it to be the very foundation of the Divine religions, a service to His Kingdom, the source of eternal life, and the greatest means of admittance into the heavenly realm.”17‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Tablets to the Hague. Available at www.bahai.org/r/749353064

STRATEGIC PLAN FOR THE ACHIEVEMENT OF PEACE

‘Abdu’l-Bahá dedicated His life to the advancement of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh and to the establishment of universal peace. His peace activities in the West include many talks given in Europe and North America. He had close contact with civic leaders and social activists and participated in the 1912 Lake Mohonk Conference on Peace and Arbitration in upstate New York attended by over 180 prominent people from the United States and other countries. He addressed a variety of American women’s organizations, gave presentations at universities and colleges, spoke in Chicago at the NAACP’s annual conference, and gave lectures at churches and synagogues.

Yet for all His courageous activities, and all the efforts of the Bahá’ís, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was greatly saddened by the world’s apparent indifference to Bahá’u’lláh’s call for global peace and to the efforts He Himself had made in the course of His travels. Shoghi Effendi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s grandson and His appointed successor, wrote: “Agony filled His soul at the spectacle of human slaughter precipitated through humanity’s failure to respond to the summons He had issued, or to heed the warnings He had given.”18Shoghi Effendi. God Passes By. Available at www.bahai.org/r/986414751

Given the turbulent condition of the world and the dangers facing humankind, He devised a detailed strategic plan to address the situation and to assign responsibility for its implementation. His plan, devised in 1916 to 1917 and set out in fourteen letters, known collectively as the Tablets of the Divine Plan, was entrusted to the members of the Bahá’í community in the United States and Canada. The pivotal goal of the Tablets of the Divine Plan is directly associated with the long-range process that will lead to the achievement of peace in the world as envisaged in Bahá’u’lláh’s writings.

Designated as “the chosen trustees and principal executors of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Divine Plan,”19Shoghi Effendi. This Decisive Hour. Available at www.bahai.org/r/194317153 the North American Bahá’ís were called upon to assume a prominent role in taking the message of Bahá’u’lláh to all the countries of the world and for effecting the transformation in values necessary for the emergence of a world order characterized by justice, unity, and peace. This great human resource – the body of willing believers in the West – was notable for its enthusiasm, determination, and deep commitment to Bahá’u’lláh’s vision for change. These communities were ideal incubators for the processes of peace.

At the time the messages of the Tablets of the Divine Plan were being written, North American Bahá’ís comprised but a small percentage of the total Bahá’ís in the world (though many had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in 1912). Commenting on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s choice of the North American Bahá’ís and the link between World War I and the Tablets of the Divine Plan, Shoghi Effendi indicated that the Divine Plan “was prompted by the contact established by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Himself, in the course of His historic journey, with the entire body of His followers throughout the United States and Canada. It was conceived, soon after that contact was established, in the midst of what was then held to be one of the most devastating crises in human history.”20Shoghi Effendi. This Decisive Hour. Available at www.bahai.org/r/257510249 Shoghi Effendi offered further comment concerning the historic bond between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the North American community: “This is the community,” he reminded us,

which, ever since it was called into being through the creative energies released by the proclamation of the Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, was nursed in the lap of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s unfailing solicitude, and was trained by Him to discharge its unique mission through the revelation of innumerable Tablets, through the instructions issued to returning pilgrims, through the despatch of special messengers, through His own travels at a later date, across the North American continent, through the emphasis laid by Him on the institution of the Covenant in the course of those travels, and finally through His mandate embodied in the Tablets of the Divine Plan.21Shoghi Effendi. God Passes By. Available at www.bahai.org/r/256927469

It is clear that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was aware of the potential capacity of the North American Bahá’ís to carry out the task with which they had been entrusted. His extensive travels in North America afforded the opportunity to assess, at first hand, the spiritual, social, and political environment of the continent and to appreciate the freedoms – intellectual, artistic, political, and, particularly, the religious freedom—inherent in North American society. And it is also apparent that He understood the spiritual possibilities of the West and the desire of women and men to seek a fuller expression of all things – of themselves, of their society, of the world.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE TABLETS OF THE DIVINE PLAN

As described above, the Tablets of the Divine Plan constitute the charter for the propagation of the Bahá’í Faith and outline ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s plan for the spiritual regeneration of the world. The letters therein set out the prerequisites for peace and assign responsibility to the North American believers “to plant the banner of His Father’s Faith . . . in all the continents, the countries and islands of the globe.”22Shoghi Effendi. God Passes By. Available at www.bahai.org/r/552193552 They focus on the work of promulgating and implementing Bahá’u’lláh’s salutary message of unity, justice, and peace in a systematic and orderly manner. They represent a strategic intervention put in place by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to ensure the ongoing and systematic dissemination of the values of peace and the promotion of activities associated with moral and social advancement. They describe a spiritually based approach to peace that is pragmatic, long-term, flexible, and durable.

In those darkest days of World War I, the means of communication between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Palestine (then under the rule of the Ottoman Empire) and the community of His followers around the world were disrupted and, for a period, severed. The first eight Tablets were written in the spring of 1916, and the second group was penned during the spring of 1917. The first group did not arrive in North America until the fall of 1916, while the delivery of the remaining Tablets was delayed until after the cessation of hostilities.23Amin Banani. Foreword to Tablets of the Divine Plan. (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1993), xxi.

The Great War of 1914-1918 rocked the very foundations of society and dramatically changed the shape of the world. The historian Margaret MacMillan provides a telling summary of the impact of the War:

Four years of war shook forever the supreme self-confidence that had carried Europe to world dominance. After the western front Europeans could no longer talk of a civilizing mission to the world. The war toppled governments, humbled the mighty and overturned whole societies. In Russia the revolutions of 1917 replaced tsarism, with what no one yet knew. At the end of the war Austria-Hungary vanished, leaving a great hole at the centre of Europe. The Ottoman empire, with its vast holdings in the Middle East and its bit of Europe, was almost done. Imperial Germany was now a republic. Old nations—Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia—came out of history to live again and new nations—Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia—struggled to be born.24Margaret MacMillan. Peacemakers: Six Months that Changed the World. (London: John Murray, 2001), 2.

The Tablets captured the mood of the day—the complex fusion of anxiety and despair, the burning desire to end a war more brutal than any the world had ever known, and a desire for a new approach to peaceful existence. Addressing this heartfelt yearning, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá offered a contrasting vision of how the world might be if it lived in harmony:

This world-consuming war has set such a conflagration to the hearts that no word can describe it. In all the countries of the world the longing for universal peace is taking possession of men. There is not a soul who does not yearn for concord and peace. A most wonderful state of receptivity is being realized. This is through the consummate wisdom of God, so that capacity may be created, the standard of the oneness of the world of humanity be upraised, and the fundamental of universal peace and the divine principles be promoted in the East and the West.25‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/500285326

In another Tablet, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá reflected on the impact of World War I on humankind and offered a context for understanding the “wisdom of this war”:

In short, after this universal war, the people have obtained extraordinary capacity to hearken to the divine teachings, for the wisdom of this war is this: That it may become proven to all that the fire of war is world-consuming, whereas the rays of peace are world-enlightening. One is death, the other is life; this is extinction, that is immortality; one is the most great calamity, the other is the most great bounty; this is darkness, that is light; this is eternal humiliation and that is everlasting glory; one is the destroyer of the foundation of man, the other is the founder of the prosperity of the human race.26‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/828798977

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s response to war, as set out in the Tablets of the Divine Plan, went far beyond providing an alternative vision. He called for constructive mobilization consistent with the local situation. For example, tapping into peoples’ receptivity to new ideas resulting from the sufferings associated with war, He directed the Bahá’ís to take steps to spread Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, and He set out other concrete actions that could be immediately taken. These activities aimed not only to enlarge the Bahá’í community but were considered essential to spreading the values of peace in the wider society. To this end, He invited “a number of souls” to “arise and act in accordance with the aforesaid conditions, and hasten to all parts of the world.…Thus in a short space of time, most wonderful results will be produced, the banner of universal peace will be waving on the apex of the world and the lights of the oneness of the world of humanity may illumine the universe.”27‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/998358260

The Tablets of the Divine Plan underlined the contribution of religion to individual and social development. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated:

Consider how the religions of God served the world of humanity! How the religion of Torah became conducive to the glory and honor and progress of the Israelitish nation! How the breaths of the Holy Spirit of His Holiness Christ created affinity and unity between divergent communities and quarreling families! How the sacred power of His Holiness Muḥammad became the means of uniting and harmonizing the contentious tribes and the different clans of Peninsular Arabia—to such an extent that one thousand tribes were welded into one tribe; strife and discord were done away with; all of them unitedly and with one accord strove in advancing the cause of culture and civilization, and thus were freed from the lowest degree of degradation, soaring toward the height of everlasting glory!28‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/191427232

Within this context, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá affirmed that the Bahá’í community’s historic mission was at heart a spiritual enterprise, and He illustrated the capacity of the community to unite peoples of different background. He wrote:

Consider! The people of the East and the West were in the utmost strangeness. Now to what a high degree they are acquainted with each other and united together! How far are the inhabitants of Persia from the remotest countries of America! And now observe how great has been the influence of the heavenly power, for the distance of thousands of miles has become identical with one step! How various nations that have had no relations or similarity with each other are now united and agreed through this divine potency! Indeed to God belongs power in the past and in the future! And verily God is powerful over all things!29‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/205096335

The community-building activities initiated by the Bahá’ís at the behest of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the diversity of the Faith’s emerging community constitute a powerful means to engage the interest and attract the collaboration of like-minded people who are also committed to the cause of enduring social change and are willing to work for the creation of a culture of peace.

The vision of the Tablets of the Divine Plan is a vision that regards all human beings as being responsible for the advancement of civilization. The Bahá’í Faith looks to ensure such advancement is possible by highlighting the pathways of unity. To initiate the processes of individual and social transformation, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá calls on his followers to embrace a series of tasks – in a sense, to get to work – so that they might

occupy themselves with the diffusion of the divine exhortations and advices, guide the souls and promote the oneness of the world of humanity. They must play the melody of international conciliation with such power that every deaf one may attain hearing, every extinct person may be set aglow, every dead one may obtain new life and every indifferent soul may find ecstasy. It is certain that such will be the consummation.30‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/258989901

Humankind is asked to flee “all ignorant prejudices” and work for the good of all. In the West, individuals are charged to commit to “the promulgation of the divine principles so that the oneness of the world of humanity may pitch her canopy in the apex of America and all the nations of the world may follow the divine policy.”31‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/785288640

The great changes described in the Tablets will evolve slowly. For though the Tablets call for a time when “the mirror of the earth may become the mirror of the Kingdom, reflecting the ideal virtues of heaven,”32‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/904315062 translating this poetic vision into a concrete plan will take time. But this delay is not cause for slowing the activities of peace, rather the scale of change demands a systematic approach to peace.33‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Ibid 3.3 For instance, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá lists countries by name and specifies the order in which tasks are to be completed.34‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Ibid., ¶6.11, ¶6.4, and ¶6.7.

But along with all His specificity, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also describes a lofty vision meant to inspire. He calls upon His followers to become “heavenly farmers and scatter pure seeds in the prepared soil,” promises that “throughout the coming centuries and cycles many harvests will be gathered,” and asks followers to “consider the work of former generations. During the lifetime of Jesus Christ, the believing, firm souls were few and numbered, but the heavenly blessings descended so plentifully that in a number of years countless souls entered beneath the shadow of the Gospel.”35‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Tablets of the Divine Plan. Available at www.bahai.org/r/434173994

LOOKING AHEAD

Written just over a century ago during one of humanity’s darkest hours, the Tablets of the Divine Plan “set in motion processes designed to bring about, in due course, the spiritual transformation of the planet.”36Universal House of Justice. From a letter to the Bahá’ís of the World dated 21 March 2009. Available at www.bahai.org/r/288100650 These letters continue to guide Bahá’ís as they pursue the current Divine Plan under the authority of the Universal House of Justice, the international governing council of the Bahá’í Faith, and they serve as an inspiration to many others who study them. In fourteen letters, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá laid out a charter for the teaching, building, and communal activities that define the Bahá’í theatre of action. While its long-term vision encompasses all humanity, the Divine Plan’s execution is tied to the Bahá’í community’s spiritual evolution and the development of its administrative institutions. It is also tied to humanity’s receptivity and willingness to pursue peace.

Today, Bahá’ís throughout the world are actively engaged in the application of the Divine Plan through a long-term process of community building inspired by the principle of the oneness of humankind. Embracing an outward-looking orientation, Bahá’ís maintain that to systematically advance a material and spiritual global civilization, the contributions of innumerable individuals, groups, and organizations is required for generations to come. The process of community building that is finding expression in Bahá’í localities throughout the world is open to all peoples regardless of race, gender, nationality, or religion.

In these communities, Bahá’ís aspire to develop patterns of life and social structures based on Bahá’u’lláh’s principles. Throughout the process they are learning how to strengthen community life based on spiritual principles including the prerequisites for the establishment of global peace as identified in the Bahá’í writings. The Plan, in both urban and rural settings, is comprised of an educational process where children, youth, and adults explore spiritual concepts, gain capacity, and apply them to their own distinct social environment. As individuals participate in this ongoing process of community building, they draw insights from science and religion’s spiritual teachings toward gaining new knowledge and insights.

The acquisition of new knowledge is continually applied to nurturing a community environment that is free from prejudice of race, class, religion, nationality, and strives to achieve the full equality of women in all the affairs of the community as well as the society at large. A natural outcome of this transformative learning process of spiritual and material education is involvement in the life of society. In this regard, Bahá’ís are engaged in two interconnected areas of action: social action and participation in the prevalent discourses of society. Social action involves the application of spiritual principles to social problems in order to advance material progress in diverse settings. Second, in diverse settings, Bahá’í institutions and agencies, in addition to individuals and organizations, whether academic or professional, or at national and international forums, also participate in important discourses prevalent in society with the goal of exploring the solutions to social problems and contributing to the advancement of society. Aware of the complex challenges that lie ahead of them in this work, Bahá’ís are working jointly with others, convinced of the unique role that religion offers in the construction of a spiritual global order.37For more detailed information please refer to message dated 18 January 2019 from the Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the World. Available at www.bahai.org/r/537332008 ; Riḍván 2021 message from the Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the World. Available at wwww.bahai.org/r/750707520

Stressing the vital significance of striving to enhance the learning processes associated with the implementation of peace, a recent message addressed to Bahá’ís and their collaborators, observed that

none who are conscious of the condition of the world can refrain from giving their utmost endeavour… The devoted efforts that you and your like-minded collaborators are making to build communities founded on spiritual principles, to apply those principles for the betterment of your societies, and to offer the insights arising—these are the surest ways you can hasten the fulfillment of the promise of world peace.38Universal House of Justice. From a message to the Bahá’ís of the World dated 18 January 2019. Available at www.bahai.org/r/276724432

The Divine Plan continues to unfold over the decades as the collective capacity of the Bahá’í community grows in tandem with the world’s openness to change. Implementation of the Plan continues and will continue so that the world might achieve “the advent of that Golden Age which must witness the proclamation of the Most Great Peace and the unfoldment of that world civilization which is the offspring and primary purpose of that Peace.”39Shoghi Effendi. Citadel of Faith: Messages to America, 1947-1957. Available at www.bahai.org/r/688620126

In October 1911, as the world teetered towards collapse and the prospects of war loomed large, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá delivered a speech in Paris to a group of individuals who were seeking creative solutions to the issues of the day. He spoke about the pragmatic relationship between “true thought” and its application. “If these thoughts never reach the plane of action,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained, “they remain useless: the power of thought is dependent on its manifestation in deeds.”40‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Paris Talks. Available at www.bahai.org/r/184033132

In this paper we explore ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s active promotion of the broad vision of peace set out in the teachings of the Bahá’í Faith and examine His contributions to mobilizing widespread support for the practice of peace. The realization of peace, as outlined in the Bahá’í writings and elucidated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, is dependent on spiritual thoughts based on spiritual virtues expressed through human deeds.

The world’s great faiths have animated civilizations throughout history. Each affirms the existence of an all-loving God and opens the doors of understanding to the spiritual dimension of life. Each cultivates the love of God and of humanity in the human heart and seeks to bring out the noblest qualities and aspirations of the human being. Each has beckoned humankind to higher forms of civilization.

Over the thousands of years of humanity’s collective infancy and adolescence, the systems of shared belief brought by the world’s great religions have enabled people to unite and create bonds of trust and cooperation at ever-higher levels of social organization―from the family, to the tribe, to the city-state and nation. As the human race moves toward a global civilization, this power of religion to promote cooperation and propel cultural evolution can perhaps be better understood today than ever before. It is an insight that is increasingly being recognized and is affirmed in the work of evolutionary psychologists and cultural anthropologists.

The teachings of the Founders of the world’s religions have inspired breathtaking achievements in literature, architecture, art, and music. They have fostered the promotion of reason, science, and education. Their moral principles have been translated into universal codes of law, regulating and elevating human relationships. These uniquely endowed individuals are referred to as Manifestations of God

in the Bahá’í writings, and include (among others) Krishna, Moses, Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus Christ, Muhammad, the Báb, and Bahá’u’lláh. History provides countless examples of how these Figures have awakened in whole populations capacities to love, to forgive, to create, to dare greatly, to overcome prejudice, to sacrifice for the common good, and to discipline the impulses of humanity’s baser instincts. These achievements can be recognized as the common spiritual heritage of the human race.

Today, humanity faces the limits of a social order inadequate to meet the compelling challenges of a world that has virtually shrunk to the level of a neighborhood. On this small planet, sovereign nations find themselves caught between cooperation and competition. The well-being of humanity and of the environment are too often compromised for national self-interest. Propelled by competing ideologies, divided by various constructs of us

versus them,

the people of the world are plunged into one crisis after another—brought on by war, terrorism, prejudice, oppression, economic disparity, and environmental upheaval, among other causes.

Bahá’u’lláh—as the latest in the series of divinely inspired moral educators Who have guided humanity from age to age—has proclaimed that humanity is now approaching its long-awaited stage of maturity: unity at the global level of social organization. He provides a vision of the oneness of humanity, a moral framework, and teachings that, founded on the harmony of science and religion, directly address today’s problems. He points the way to the next stage of human social evolution. He offers to the peoples of the world a unifying story consistent with our scientific understanding of reality. He calls on us to recognize our common humanity, to see ourselves as members of one family, to end estrangement and prejudice, and to come together. By doing so, all peoples and every social group can be protagonists in shaping their own future and, ultimately, a just and peaceful global civilization.

ONE HUMANITY, ONE UNFOLDING FAITH

We live in a time of rapid, often unsettling change. People today survey the transformations underway in the world with mixed feelings of anticipation and dread, of hope and anxiety. In the societal, economic, and political realms, essential questions about our identity and the nature of the relationships that bind us together are being raised to a degree not seen in decades.

Progress in science and technology represents hope for addressing many of the challenges that are emerging, but such progress is itself a powerful force of disruption, changing the ways we make choices, learn, organize, work, and play, and raising moral questions that have not been encountered before. Some of the most formidable problems facing humanity—those dealing with the human condition and requiring moral and ethical decisions—cannot be solved through science and technology alone, however critical their contributions.

The teachings of Bahá’u’lláh help us understand the transformations underway. At the heart of His message are two core ideas. First is the incontrovertible truth that humanity is one, a truth that embodies the very spirit of the age, for without it, it is impossible to build a truly just and peaceful world. Second is the understanding that humanity’s great faiths have come from one common Source and are expressions of one unfolding religion.

In His writings, Bahá’u’lláh raised a call to the leaders of nations, to religious figures, and to the generality of humankind to give due importance to the place of religion in human advancement. All of the Founders of the world’s great religions, He explained, proclaim the same faith. He described religion as the chief instrument for the establishment of order in the world and of tranquility amongst its peoples

and referred to it as a radiant light and an impregnable stronghold for the protection and welfare of the peoples of the world.

In another of His Tablets, He states that the purpose of religion is to safeguard the interests and promote the unity of the human race, and to foster the spirit of love and fellowship amongst men.

The religion of God and His divine law,

He further explains, are the most potent instruments and the surest of all means for the dawning of the light of unity amongst men. The progress of the world, the development of nations, the tranquility of peoples, and the peace of all who dwell on earth are among the principles and ordinances of God. Religion bestoweth upon man the most precious of all gifts, offereth the cup of prosperity, imparteth eternal life, and showereth imperishable benefits upon mankind.

THE DECLINE OF RELIGION

Bahá’u’lláh was also deeply concerned about the corruption and abuse of religion that had come to characterize human societies around the planet. He warned of the inevitable decline of religion’s influence in the spheres of decision making and on the human heart. This decline, He explained, sets in when the noble and pure teachings of the moral luminaries who founded the world’s great religions are corrupted by selfish human ideas, superstition, and the worldly quest for power. Should the lamp of religion be obscured,

explained Bahá’u’lláh, chaos and confusion will ensue, and the lights of fairness and justice, of tranquility and peace cease to shine.

From the perspective of the Bahá’í teachings, the abuses carried out in the name of religion and the various forms of prejudice, superstition, dogma, exclusivity, and irrationality that have become entrenched in religious thought and practice prevent religion from bringing to bear the healing influence and society-building power it possesses.

Beyond these manifestations of the corruption of religion are the acts of terror and violence heinously carried out in, of all things, the name of God. Such acts have left a grotesque scar on the consciousness of humanity and distorted the concept of religion in the minds of countless people, turning many away from it altogether.

The spiritual and moral void resulting from the decline of religion has not only given rise to virulent forms of religious fanaticism, but has also allowed for a materialistic conception of life to become the world’s dominant paradigm.

Religion’s place as an authority and a guiding light both in the public sphere and in the private lives of individuals has undergone a profound decline in the last century. A compelling assumption has become consolidated: as societies become more civilized, religion’s role in humanity’s collective affairs diminishes and is relegated to the private life of the individual. Ultimately, some have speculated that religion will disappear altogether.

Yet this assumption is not holding up in the light of recent developments. In these first decades of the 21st century, religion has experienced a resurgence as a social force of global importance. In a rapidly changing world, a reawakening of humanity’s longing for meaning and for spiritual connection is finding expression in various forms: in the efforts of established faiths to meet the needs of rising generations by reshaping doctrines and practices to adapt to contemporary life; in interfaith activities that seek to foster dialogue between religious groups; in a myriad of spiritual movements, often focused on individual fulfillment and personal development; but also in the rise of fundamentalism and radical expressions of religious practice, which have tragically exploited the growing discontent among segments of humanity, especially youth.

Concurrently, national and international governing institutions are not only recognizing religion’s enduring presence in society but are increasingly seeing the value of its participation in efforts to address humanity’s most vexing problems. This realization has led to increased efforts to engage religious leaders and communities in decision making and in the carrying out of various plans and programs for social betterment.

Each of these expressions, however, falls far short of acknowledging the importance of a social force that has time and again demonstrated its power to inspire the building of vibrant civilizations. If religion is to exert its vital influence in this period of profound, often tumultuous change, it will need to be understood anew. Humanity will have to shed harmful conceptions and practices that masquerade as religion. The question is how to understand religion in the modern world and allow for its constructive powers to be released for the betterment of all.

RELIGION RENEWED

The great religious systems that have guided humanity over thousands of years can be regarded in essence as one unfolding religion that has been renewed from age to age, evolving as humanity has moved from one stage of collective development to another. Religion can thus be seen as a system of knowledge and practice that has, together with science, propelled the advancement of civilization throughout history.

Religion today cannot be exactly what it was in a previous era. Much of what is regarded as religion in the contemporary world must, Bahá’ís believe, be re-examined in light of the fundamental truths Bahá’u’lláh has posited: the oneness of God, the oneness of religion, and the oneness of the human family.

Bahá’u’lláh set an uncompromising standard: if religion becomes a source of separation, estrangement, or disagreement—much less violence and terror—it is best to do without it. The test of true religion is its fruits. Religion should demonstrably uplift humanity, create unity, forge good character, promote the search for truth, liberate human conscience, advance social justice, and promote the betterment of the world. True religion provides the moral foundations to harmonize relationships among individuals, communities, and institutions across diverse and complex social settings. It fosters an upright character and instills forbearance, compassion, forgiveness, magnanimity, and high-mindedness. It prohibits harm to others and invites souls to the plane of sacrifice, that they may give of themselves for the good of others. It imparts a world-embracing vision and cleanses the heart from self-centeredness and prejudice. It inspires souls to endeavor for material and spiritual betterment for all, to see their own happiness in that of others, to advance learning and science, to be an instrument of true joy, and to revive the body of humankind.

True religion is in harmony with science. When understood as complementary, science and religion provide people with powerful means to gain new and wondrous insights into reality and to shape the world around them, and each system benefits from an appropriate degree of influence from the other. Science, when devoid of the perspective of religion, can become vulnerable to dogmatic materialism. Religion, when devoid of science, falls prey to superstition and blind imitation of the past. The Bahá’í teachings state:

Put all your beliefs into harmony with science; there can be no opposition, for truth is one. When religion, shorn of its superstitions, traditions, and unintelligent dogmas, shows its conformity with science, then will there be a great unifying, cleansing force in the world which will sweep before it all wars, disagreements, discords and struggles—and then will mankind be united in the power of the Love of God.

True religion transforms the human heart and contributes to the transformation of society. It provides insights about humanity’s true nature and the principles upon which civilization can advance. At this critical juncture in human history, the foundational spiritual principle of our time is the oneness of humankind. This simple statement represents a profound truth that, once accepted, invalidates all past notions of the superiority of any race, sex, or nationality. It is more than a mere call to mutual respect and feelings of goodwill between the diverse peoples of the world, important as these are. Carried to its logical conclusion, it implies an organic change in the very structure of society and in the relationships that sustain it.

THE EXPERIENCE OF THE BAHÁ’Í COMMUNITY

Inspired by the principle of the oneness of humankind, Bahá’ís believe that the advancement of a materially and spiritually coherent world civilization will require the contributions of countless high-minded individuals, groups, and organizations, for generations to come. The efforts of the Bahá’í community to contribute to this movement are finding expression today in localities all around the world and are open to all.

At the heart of Bahá’í endeavors is a long-term process of community building that seeks to develop patterns of life and social structures founded on the oneness of humanity. One component of these efforts is an educational process that has developed organically in rural and urban settings around the world. Spaces are created for children, youth, and adults to explore spiritual concepts and gain capacity to apply them to their own social environments. Every soul is invited to contribute regardless of race, gender, or creed. As thousands upon thousands participate, they draw insights from both science and the world’s spiritual heritage and contribute to the development of new knowledge. Over time, capacities for service are being cultivated in diverse settings around the world and are giving rise to individual initiatives and increasingly complex collective action for the betterment of society. Transformation of the individual and transformation of the community unfold simultaneously.

Beyond efforts to learn about community building at the grass roots, Bahá’ís engage in various forms of social action, through which they strive to apply spiritual principles in efforts to further material progress in diverse settings. Bahá’í institutions and agencies, as well as individuals and organizations, also participate in the prevalent discourses of their societies in diverse spaces, from academic and professional settings, to national and international forums, all with the aim of contributing to the advancement of society.

As they carry out this work, Bahá’ís are conscious that to uphold high ideals is not the same as to embody them. The Bahá’í community recognizes that many challenges lie ahead as it works shoulder to shoulder with others for unity and justice. It is committed to the long-term process of learning through action that this task entails, with the conviction that religion has a vital role to play in society and a unique power to release the potential of individuals, communities, and institutions.

Although the 20th century witnessed the increasing recognition of principles such as universal human rights, democratic ideals, the equality of human beings, social justice, the peaceful resolution of conflict, and condemnation of the barbarism of war, it was nevertheless one of the bloodiest centuries in all human history. Such a development was unpredicted by classical sociological theorists writing in the second half of the 19th century, who either did not devote much attention to the question of war and peace or were optimistic about the prospects for peace in the 20th century. While war and peace were central questions in the social theories of both Auguste Comte (1798–1857),1Auguste Comte, Introduction to Positive Philosophy (Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1970). the founder of positivism, and Herbert Spencer (1820–1903),2Herbert Spencer, Evolution of Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967). the founder of evolutionary and synthetic philosophy, for example, both conceived of social change as an evolutionary movement towards progress and characterized the emerging modern society as essentially peaceful—one in which military conquest aimed at the acquisition of land would be replaced with economic and industrial competition.3This is part of Comte’s law of three stages. According to this idea, all societies evolve by going through religious/theological, metaphysical/philosophical, and scientific/positive stages. Spencer defined a military society as one in which the social function of regulation is dominant, while in an industrial society the economic function predominates. Other classical theorists generally assumed that war among nations was a thing of the past.4Contrary to the popular perception, Durkheim, Marx, and Weber rarely engaged in a direct discussion of war or peace. Only after the onset of the World War I did Durkheim, Simmel, and Mead side with their own countries and discuss the issue. Such optimism was partly rooted in the relative security of Europe during the 19th century where, between the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 and the onset of World War I in 1914 there was a relatively long stage of peace, interrupted mainly by the German-French war of 1870. However, this security was a mere illusion, accompanied as it was by increasing militarism and nationalism in Europe and the vast scale of war and genocide perpetrated by European powers in their pursuit of colonial conquest in Africa and other parts of the world.

Standing in contrast to the misplaced optimism of the classical 19th century sociologists is the spiritual figure of Bahá’u’lláh, who was born in 1817 in Persia and initiated a transformative global religion centered on the urgency and necessity of peace making. He perceived that both the institutional structures of the 19th century and their cultural orientation promoted various forms of violence, including international wars. The significance of Bahá’u’lláh and His insights as they apply to peace movements and peace studies is evident through an examination of His worldview and of the manner in which His writings reconstruct foundational concepts such as mysticism, religion, and social order—emphasizing the replacement of the sword with the word.

BAHÁ’U’LLÁH AND THE REMOVAL OF THE SWORD

Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alíy-i-Núrí, who took the title Bahá’u’lláh (the Glory of God

), was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1817. As a young man, Bahá’u’lláh accepted the claim of the young merchant from Shiraz known as the Báb (the Gate

) to be the Promised One of Shí‘ih Islam. Both the clerics and state authorities in Iran declared the Báb’s ideas heretical and dangerous and unleashed a systematic campaign of genocide directed at His followers, the Bábís. The Báb Himself was executed in 1850—only six years after the announcement of His mission. While the writings of the Báb provided fresh and innovative interpretations of religious ideas, they pointed to the imminent appearance of a new Manifestation (prophet or messenger) of God and defined His entire revelation as a preparation for the coming of that great spiritual educator. During a massacre of the Bábís in 1852, Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned in a dungeon in Tehran, where He received an epoch-making experience of revelation and perceived Himself to be the Promised One of all religions, including the Bábí Faith. After four months of imprisonment, and the confiscation of all His property, He was exiled to the Ottoman Empire, first to Baghdad, then in 1863 to Constantinople (Istanbul), and from there to Adrianople (Edirne), and finally, in 1868, to the fortress city of ‘Akká in the Holy Land, where He died in 1892.

Although Bahá’u’lláh founded a new religion, the meaning, and particularly the end purpose, of religion is transformed in His writings. As traditionally conceived, religion is often focused on a set of theological doctrines about God, prophets, the next world, and the Day of judgment. While these concepts are discussed and elucidated in His writings, Bahá’u’lláh emphasizes that He has come to renew and revitalize humanity, to reconstruct the world, and to bring peace. In His final work, the Book of the Covenant, He describes the purpose of His life, sufferings, revelation and writings in this way:

The aim of this Wronged One in sustaining woes and tribulations, in revealing the Holy Verses and in demonstrating proofs hath been naught but to quench the flame of hate and enmity, that the horizon of the hearts of men may be illumined with the light of concord and attain real peace and tranquillity.5Bahá’u’lláh, Kitáb-i-‘Ahd (Book of the Covenant), in Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978), 219.

In other words, affirming spiritual principles is inseparable from transforming the social order and from replacing hatred and violence with love and universal peace. From a Bahá’í point of view, then, religion must be the cause of unity and concord among human beings, and if it becomes a cause of enmity and violence, it is better not to have religion.6See for example, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks. Making peace is the essence of Bahá’u’lláh’s normative orientation and worldview. It is ironic, therefore, that both the King of Iran and the Ottoman Sultan rose together against Bahá’u’lláh to silence His voice by intriguing to exile Him to the city of ‘Akká; however, their oppressive decision in the end only exemplified the Hegelian concept of the cunning of Reason,

7Georg W. F. Hegel, Reason in History (New York: Liberal Arts Press, 1953), 25–56. in which Reason realizes its plan through the unintended consequences of actions by individuals whose intent is their own selfish desires. As Bahá’u’lláh has frequently stated, His response to this final exile ordered by these two kings was to publicly announce His message to the rulers of the world. Upon arrival in ‘Akká, He wrote messages to world leaders, including those of Germany, England, Russia, Iran, and France, as well as to the Pope, explicitly declaring His cause and calling them all to unite and bring about world peace. The second irony is that it was through this exile that He was brought to the Holy Land, where the coming of final peace in the world is prophesied to take place, when the wolf and lamb will feed together and swords will be beaten into plowshares.8Isaiah 11:6 and 2:4.

In order to better understand the vital connection between Bahá’u’lláh’s revelation and His concern with peace, let us examine that experience of revelation in the Tehran dungeon in 1852 which marks the birth of the Bahá’í Faith. Bahá’u’lláh describes this experience:

One night, in a dream, these exalted words were heard on every side: Verily, We shall render Thee victorious by Thyself and by Thy Pen. Grieve Thou not for that which hath befallen Thee, neither be Thou afraid, for Thou art in safety. Erelong will God raise up the treasures of the earth—men who will aid Thee through Thyself and through Thy Name, wherewith God hath revived the hearts of such as have recognized Him.

9Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, accessed 7 June 2018, http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/epistle-son-wolf/#f=f2-35

This brief statement epitomizes many of the central teachings of the Bahá’í Faith, one of the most important of which is the replacement of the sword with the word. The victory of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh will take place through the person and character of Bahá’u’lláh and by means of His pen: words and their embodiment in deeds are the only means through which the message of Bahá’u’lláh can be promoted. Thus, the Islamic concept of jihad is abrogated, as is any concept of the religion and its propagation that includes violence, discrimination, coercion, avoidance, and hatred of others. Bahá’u’lláh continually presents the elimination of religious fanaticism, hatred, and violence as one of the main goals of His revelation.

This first experience of revelation defines the substantive message of the new religion in terms of the method of its promotion: A peaceful and dialogical method is the very essence of the new concept of peace and justice. Unlike doctrines that justify forms of violence and oppression as acceptable or even necessary methods of establishing peace and justice in the world, Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings categorically affirm the unity of substance and method in peace making: peace is realized through the way we live, the words we use, and the means we employ to bring about justice, unity, and peace. For Bahá’u’lláh, the time has come to reject the law of the jungle not only in our normative pronouncements about humanity but also in the methods we pursue in order to realize lofty ideals.10See Saiedi, From Oppression to Empowerment,The Journal of Bahá’í Studies 26:1–2 (Spring/Summer 2016), 28–30.

The word, or the pen, is central in Bahá’í philosophy. In the experience of revelation, there is a conversation between God and Bahá’u’lláh, which is an exact repetition of the conversation between God and Moses. According to the Qur’án, God gives two proofs to Moses: His staff and His shining hand. When Moses places His staff on the ground, it becomes a mighty snake, causing Him to become afraid and stand back. God tells Him: Be Thou not afraid, for Thou art in safety.

11Qur’an 28:31. These same words are now uttered by God to Bahá’u’lláh,12While in translation they may appear to be slightly different, they are identical in the original Arabic. implying that the staff of Moses has been replaced by the pen of Bahá’u’lláh as His mighty proof of truth. Likewise, instead of the hand of Moses, the entire being and character of Bahá’u’lláh have become His new evidence. The immediate implication is the unity of Bahá’u’lláh and Moses. This reflects one of Bahá’u’lláh’s central teachings: that all the Manifestations of God are one and that They convey the same fundamental spiritual truth, leading to the principle of the harmony and unity of all religions.

This replacement of the staff with the pen further emphasizes the fact that His cause is rendered victorious through the effect of His words, rather than the performance of supernatural phenomena, or miracles; His message and His teachings constitute the supreme evidence of His truth. This replacement of physical miracles with the miracle of the spirit, namely the Word, is one of the central distinguishing features of Bahá’u’lláh’s worldview. But the most direct expression of the centrality of the pen in Bahá’u’lláh’s revelation is the new definition and conception of the human being offered in this first experience of revelation. The assertion that the cause of Bahá’u’lláh can only be rendered victorious by the pen implies that each soul possesses the capacity to independently recognize spiritual truth. Bahá’u’lláh frequently points out that all humans are created by God as mirrors of divine attributes, and because all individuals are responsible for realizing this divine gift, all the writings of Bahá’u’lláh, in one way or another, call for spiritual autonomy; no one should blindly follow or imitate any other in spiritual, political, and ethical issues. That is why priesthood has been eliminated in the Bahá’í religion and all Bahá’ís are equally and directly responsible before God. The implication of this spiritual autonomy is the utilization of democratic forms of decision making, as characterizes the Bahá’í administrative institutions. However, this form of democracy transcends the materialistic and partisan definition of the prevalent forms in society. Rather, it is a democracy of consultation based on a spiritual definition of reality that views all humans as noble beings endowed with rights.

One final implication of this first experience of revelation needs to be emphasized. According to Bahá’u’lláh’s description, the message of God was brought to Him by a Maid of Heaven. While God, the unknowable, is neither male nor female, the revelation of God through this Word, the supreme sacred reality in the created world, is presented as a feminine reality. Bahá’u’lláh received His revelation not from a tree, a bird, or a male angel, but rather from a female angel who metaphorically symbolizes the inner mystical truth of all the prophets of God. Therefore, the very inception of the Bahá’í revelation is characterized by a fundamental re-examination of the station of women. They are no longer the embodiments and symbols of selfish desires, irrationality, corruption, and worldly attraction; instead, they represent the supreme reflection of God in this world. At the same time, the removal of the sword in this first experience of revelation is a revolutionary critique of patriarchal culture and worldview. These two points are inseparable. The realization of a culture of peace requires the equality and unity of men and women, as violence and patriarchy are inseparable.

FROM WORD ORDER TO WORLD ORDER

The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh cover a period of forty years, from His imprisonment in the Tehran dungeon in 1852 to His passing in 1892. In the following passage, He describes the purpose and the stages of His writings:

Behold and observe! This is the finger of might by which the heaven of vain imaginings was indeed cleft asunder. Incline thine ear and Hear! This is the call of My Pen which was raised among mystics, then divines, and then kings and rulers.13Bahá’u’lláh, Ishráqát (Tehran: Mu’assisiy-i-Millíy-i-Matbú‘át-i-Amrí, n.d.), 260. Provisional translation.

In the first part of this statement, Bahá’u’lláh presents the contrasting images of the finger of might

and the heaven of vain imaginings

. While the idea of cleaving the moon is attributed to the prophet Muhammad, now Bahá’u’lláh’s pen is rending not only the moon but the entire heaven, which represents the illusions, idle fancies, superstitions, and misconceptions that have erected walls of estrangement between human beings, have enslaved them, and have reduced their culture to the level of the animal. Bahá’u’lláh emphasizes that violence, oppression, and hatred are embodiments of vain imaginings and illusions constructed by human beings. Now, through his pen, He has come to tear away these veils, extinguish the fire of enmity and hatred, and bring people together.

In the second part of this statement, Bahá’u’lláh identifies the stages and order of His words, which were first addressed to mystics, then to divines, and finally to the kings and rulers of the world. His first writings, those written between 1852 and 1859, including the time He lived in Iraq, primarily address mystical concepts and categories.14See The Call of the Divine Beloved: Selected Mystical Works of Bahá’u’lláh (Haifa, Bahá’í World Centre, 2018), https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/call-divine-beloved/. Those of the second stage, encompassing His writings between 1859 and 1867, address the religious leaders and their interpretation of religion. Finally His writings from 1868 on, directed both to the generality of humankind and to the kings and rulers of the world, address social and political questions. Each stage emphasizes a certain principle of Bahá’u’lláh’s worldview, following the sequence of His spiritual logic. The principles corresponding to these stages are as follows: a spiritual interpretation of reality, historical consciousness—even the historicity of the words of God—and global consciousness. The worldview of Bahá’u’lláh is defined by the mutual interdependence of these three principles.

Each stage of the writings of Bahá’u’lláh aims to reinterpret and reconstruct traditional ideas and worldviews. Therefore, the dynamics of His writings can be described by His reconstruction of mysticism, religion, and the social order.

1. RECONSTRUCTION OF MYSTICISM

In His earlier writings, Bahá’u’lláh directly engages with Persian and Islamic forms of mysticism; through these and His later writings, He reconstructs mysticism so as to realize its full potential. To understand this point, it is useful to refer to the twin concepts of the arc of descent (qaws-i-nuzúl) and arc of ascent (qaws-i-ṣu‘úd) which comprise the spiritual or mystical journey. The arc of descent is normally perceived as the descent of reality from God—the dynamics of material creation, culminating in the emergence of human life. As a consequence, however, human beings are estranged from their origin and their own truth, which is the unity of God. This yearning for reunion, in turn, initiates the arc of ascent, the mystical journey of the soul’s return to its source. The arc of ascent, as seen, for example, in the Seven Valleys, transcends the realm of conflict and plurality to discover the underlying truth of all reality, namely God.15 The stages of spiritual ascent are frequently referred to as seven valleys or seven cities. In ‘Aṭṭár’s Conference of the Birds these stages are: search/quest, love, knowledge, contentment/independence, unity, wonderment/bewilderment, and annihilation in God. Baha’u’llah’s Seven Valleys employs these stages, but He makes a slight change in the order, bringing contentment/independence after unity. See The Call of the Divine Beloved. With the annihilation of self that is found in this unity, one is assumed to have reached the zenith of the arc of ascent.

Although in traditional views of mystical consciousness, the zenith of the arc of ascent is the highest and end point of the spiritual journey, in reality this is just the beginning of a new stage. But in traditional consciousness all humans become sacred and equal only in God. In other words, only when living human beings, made of flesh and blood, are divested of their various determinations and turned into an abstraction do they become noble and sacred. For example, only when women are no longer women—that is, when their concrete determinations are negated and annulled in God—do they become equal to men. But concrete, living women remain inferior to men in rights, spiritual station, and rank. Thus despite the claim to see God in everything, the presence of social inequalities including slavery, patriarchy, religious discrimination, political despotism, and caste-like distinctions could go unchallenged.

For that reason, we need a further arc of descent

to bring the fundamental insight and achievement of mystic oneness down to earth. In other words, after tracing the arc of ascent and attaining the consciousness of unity, one must be able to descend once again into the world of concrete plurality and time and maintain the consciousness of unity without being imprisoned in the consciousness of conflict and estrangement. In this way, the wayfarer is transformed into a new being who sees the unity of all in the concrete diversity of the world; in this arc of descent, one comes to see in all people their truth, or their divine attributes. The result of this consciousness is the end of the logic of separation, discrimination, prejudice, and hatred, and the beginning of the culture of the oneness of the human race, encompassing equal rights of all humans, the equality of men and women, religious tolerance and unity, and universal love for all people. Thus, according to Bahá’u’lláh, the real task of the mystic is not just the inward transformation of the annihilation of self in God but to transform the world so that the mystical truth of all human beings is manifested in the relations, structures, and institutions of social order. Since all beings become reflections of God, God and his unity are recognized within the diversity of moments and beings, resulting in the worldview of unity in diversity.

2. RECONSTRUCTION OF RELIGION

The reconstruction of religion is, in fact, the first stage of the new arc of descent. In this first step, one descends from the unity of God and eternity to the diversity of the prophets and Manifestations of God. Here, history reveals a unity in diversity that reflects in its dynamics the unity of God: the Bahá’í view finds all the Manifestations of God to be one and the same, because they are reflections of divine unity and divine attributes. Since God is defined in the Torah, Gospel, and Qur’án as being the First and the Last, all the Manifestations are also the first and the last.16Examples are Isaiah 44:6 and 48:12, Revelation 1:8 and 22:13, and Qur’án 57:2. They are also the return of each other. Bahá’u’lláh views the realm of religion as the reflection of both diversity (of historical progress) and unity (of all the prophets). He says:

It is clear and evident to thee that all the Prophets are the Temples of the Cause of God, Who have appeared clothed in divers attire. If thou wilt observe with discriminating eyes, thou wilt behold Them all abiding in the same tabernacle, soaring in the same heaven, seated upon the same throne, uttering the same speech, and proclaiming the same Faith. Such is the unity of those Essences of Being, those Luminaries of infinite and immeasurable splendor! Wherefore, should one of these Manifestations of Holiness proclaim saying: I am the return of all the Prophets,

He, verily, speaketh the truth. In like manner, in every subsequent Revelation, the return of the former Revelation is a fact, the truth of which is firmly established.17Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-i-Iqán: The Book of Certitude (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1983), 153–54.

In other words, the Word of God, which is the essence of all religions, is a living and dynamic reality. It is one Word that, at different historical moments, appears in new forms. The different prophets are like the same sun that appears at different times at a different place on the horizon. While the traditional approach to religion usually reduces the identity of the sun to its historically specific horizon and therefore emphasizes opposition and hostility among various religions, Bahá’u’lláh identifies the truth of all religions as one and calls for the unity of religions. In Bahá’u’lláh’s view, a major cause of violence, war, and oppression in the world is religious fanaticism created by the vain imaginings of religious leaders. He warned: Religious fanaticism and hatred are a world-devouring fire whose violence none can quench. The Hand of Divine power can, alone, deliver mankind from this desolating affliction.

18Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, accessed 8 June 2018, http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/epistle-son-wolf/#f=f2-19. The establishment of peace, then, requires overcoming such religious hatred and discord.

3. RECONSTRUCTION OF THE WORLD

The second step of the new arc of descent relates to the wayfarer’s descent into the world. Here, the consciousness of unity necessarily leads to the principle of the oneness of humankind as well as to universal peace. In traditional religious consciousness, the relationship between the created and the Creator is repeated in all forms of social relations. Thus, the relation between men and women, kings and subjects, free persons and slaves, believers and non-believers, and even clerics and laymen repeat the relation between God and human beings. In this way, the illusion is created that domination, discrimination, violence, and opposition are legitimized by religion. In contrast, Bahá’u’lláh explains that the relation that truly obtains is that because all are created by God and are servants of God, all are equal. Instead of repeating in the realm of social order the relation of God to the created world, the servitude of all before God denotes the equality and nobility of all human beings. The task of true mysticism therefore is not to escape from the world, but rather to transform it so that it becomes a mirror of the republic of spirit or the kingdom of God. Bahá’u’lláh’s global consciousness and His concept of peace are embodiments of this reinterpretation of the world and social order, as reflected in the following statement in which He redefines what it is to be human:

That one indeed is a man who, today, dedicateth himself to the service of the entire human race. The Great Being saith: Blessed and happy is he that ariseth to promote the best interests of the peoples and kindreds of the earth. In another passage He hath proclaimed: It is not for him to pride himself who loveth his own country, but rather for him who loveth the whole world. The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.19Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Maqṣúd (Tablet of Maqṣúd), Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, 167.

The purpose of Bahá’u’lláh’s reinterpretation of mysticism, religion, and social order is to bring about a culture of unity in diversity and to institutionalize universal peace in the world. To discuss His specific concept of peace, it is necessary first to review the existing theories of peace in the social sciences and then identify the structure of Bahá’u’lláh’s vision.

MAIN THEORIES OF PEACE

With the outbreak of World War I, most social theorists took the side of their own country in the conflict and, in some cases, glorified war. Georg Simmel identifies war as an absolute situation

in which ordinary, selfish preoccupations of individuals living in an impersonal economy are placed in an ultimate life-and-death situation. Thus, he concludes, war liberates the moral impulse from the boredom of routine life and makes individuals willing to sacrifice their lives for the good of society.20Georg Simmel, Der Krieg und die Geistigen Entscheidungen (Munich: Duncker and Humblot, 1917). On the other side, Durkheim and Mead both take strong positions against Germany. Discussing Treitschke’s worship of war and German superiority, Durkheim writes of a German mentality