In country after country, the bicentenary of the Birth of the Báb has been celebrated by people representing the rich diversity of the human race, giving rise to countless expressions of art, music, and acts of selfless service in honor of His life and teachings. As part of the efflorescence of activities during this period, Romanian artist Simina Boicu Rahmatian has prepared twenty-five illustrations that depict some of the most significant sites related to the brief but stirring history of the Bábí Faith. The hand-drawn illustrations that follow invite us to immerse ourselves in the “marvelous happenings that…heralded the advent of the Founder of the Bábí Dispensation, the dramatic circumstances of His own eventful life, the miraculous tragedy of His martyrdom, the magic of His influence exerted on the most eminent and powerful among His countrymen.”1Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh [US Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1991] 124 The sepia tones transport us back to the nineteenth century. The contrast between light and shadow brings to life the buildings, towns and landscapes that form the backdrop against which a new religion came into existence. Yet, these images are seldom accompanied by the silhouettes of human beings; it is we the viewers who are invited to step into those scenes and imagine the settings and circumstances in which an extraordinary chapter of humanity’s spiritual evolution unfolded.

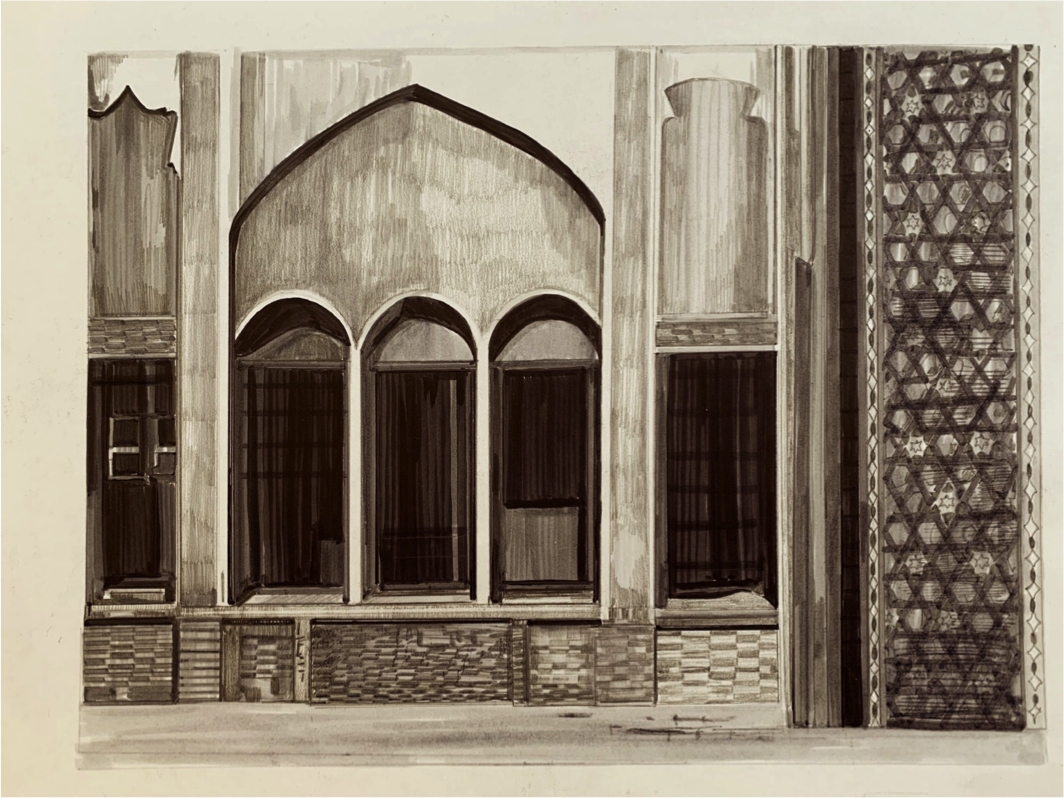

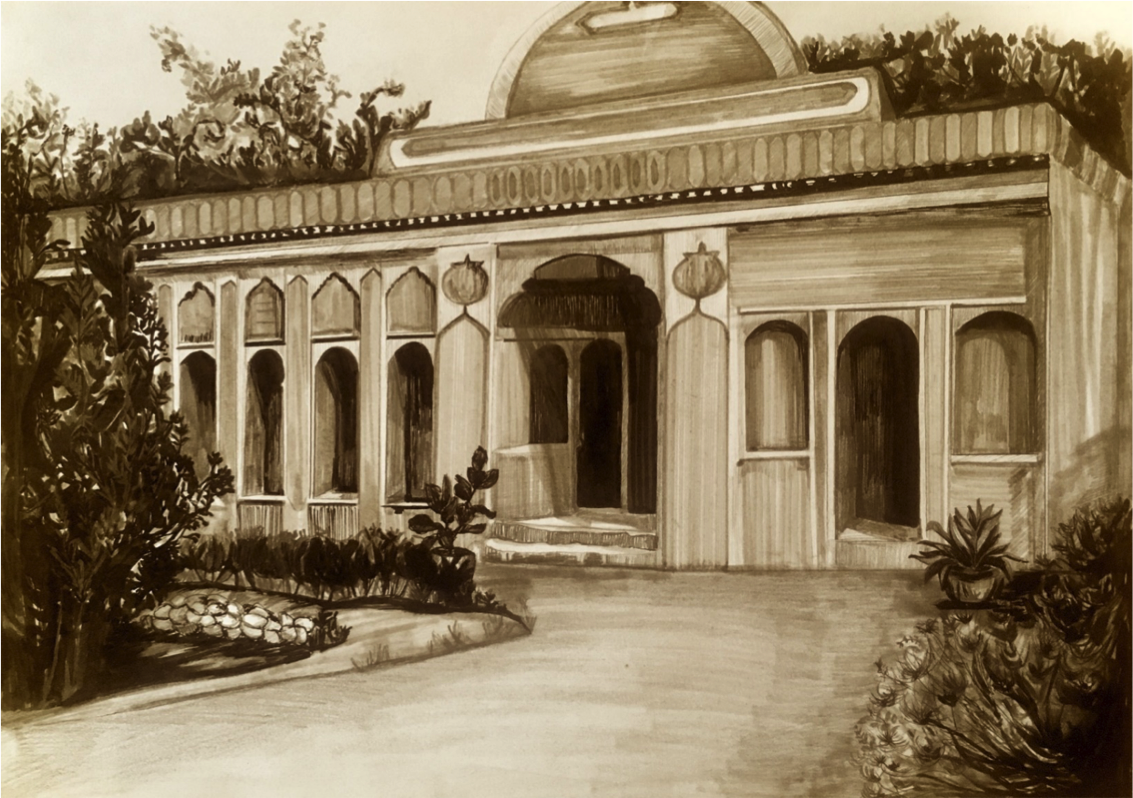

Some of the illustrations depict historic Oriental edifices: the Shrine of the Imám Ḥusayn in Karbala (no. 5), a well-known mosque and marketplace in Baghdad (no. 10), and the Masjid-i-Vakíl of Shiráz (no. 11). Also depicted are settings of sites more specifically associated with Bábí history: The front door of the Báb’s house in Shiráz (no. 3) is shut before our eyes, but our minds are invited in to imagine that fateful evening of May 22, 1844, when the Báb announced to His first disciple that He was the Promised One of Islam and the Gate (Báb, in Arabic) to a new age for humankind. While looking at the desolate castles of Máh-kú and Chihríq (nos. 14 and 15), where the Báb was imprisoned from 1847 to 1850, we are reminded of His isolation and deprivation; as He wrote, “there is not at night even a lighted lamp.”2Selections from the Writings of the Báb [Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978] 87 The sun-drenched barrack square of Ṭabríz (no. 20), where the Báb was executed, calls to our minds that unique historic moment when He, the target of hundreds of bullets, was nowhere to be found after the thick cloud of smoke cleared. Thousands, crowded around the city square, witnessed that remarkable scene. Other pictures remind us of the heroism of tens of thousands of His followers who courageously advanced a Cause that was destined to change the world. We visit the Sabzih-Maydán of Tehran (no. 18), where a young Iranian met his death singing a couplet from Rúmí: “In one hand the wine-cup, in one hand the tresses of the Friend. Such a dance in the midst of the market-place is my desire!“3Edward G. Browne, ed., A Traveller’s Narrative [Cambridge University Press, 1891] 333-4, Note T We stand before Tehran’s Gate of Naw (no. 22), on whose sides the remains of many of the Bábís were hung. We reflect somberly at Zanján’s square (no. 21), another theater of a terrible slaughter.

In the opening and concluding scenes of the collection, the artist portrays the cypress grove located at the south side of the Shrine of the Báb. The first image (no. 1) depicts the grove as seen from below in the early 1900s; the final image (no. 25) is the view from above that we see today. In the former, we can imagine Bahá’u’lláh standing beside the grove and instructing ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to house the remains of the Báb in the land just below those trees. In the latter, we see Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of the Shrine of the Báb realized in “the Queen of Carmel enthroned on God’s Mountain, crowned in glowing gold, robed in shimmering white, girdled in emerald green, enchanting every eye from air, sea, plain and hill.”4Shoghi Effendi, Messages to the Baha’i World – 1950-1957 [Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971] 169

In the visual journey ahead, we find the embodiment of these poignant words written by Shoghi Effendi in 1944:

We behold, as we survey the episodes of this first act of a sublime drama, the figure of its Master Hero, the Báb, arise meteor-like above the horizon of Shíráz, traverse the sombre sky of Persia from south to north, decline with tragic swiftness, and perish in a blaze of glory. We see His satellites, a galaxy of God-intoxicated heroes, mount above that same horizon, irradiate that same incandescent light, burn themselves out with that self-same swiftness, and impart in their turn an added impetus to the steadily gathering momentum of God’s nascent Faith.5Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By [Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974] 3

As the world endures a period of heightened crisis, may we be reminded of the extraordinary Figure of the Báb, Who was able to “illuminate a society and an age shrouded in darkness.”6October 2019 message of the Universal House of Justice to all who have come to honour the Herald of a new Dawn

Julio Savi, May 2020

Thirty years ago, the Bahá’í community of Iran embarked on a remarkable endeavor. Denied access to formal education by the country’s authorities after their numerous appeals, they set up an informal program of higher education in basements and living rooms throughout the country with the help of Bahá’í professors and academics that had been fired from their posts because of their faith. This gradually came to be known as the Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education (BIHE).

Since its inception, BIHE has helped educate thousands of individuals, many of whom have been accepted into nearly 100 universities around the world to pursue graduate studies. Many BIHE graduates that complete their post-graduate studies abroad will return to Iran to serve their communities.

Thanks to advances in technology, BIHE’s students are now taught by professors from across the globe. Those who offer their expertise and knowledge to the education of Bahá’í youth in Iran, have witnessed first-hand the students’ high ideals and commitment to the pursuit of knowledge.

“The Bahá’í response to injustice is neither to succumb in resignation nor to take on the characteristics of the oppressor,” explained Diane Ala’i, representative of the Bahá’í International Community to the United Nations in Geneva, quoting a letter from the Universal House of Justice.

“This,” she said, “is the fundamental definition of constructive resilience.”

“Of course, the Bahá’í s are not the only ones that have responded non-violently and positively to oppression, but they are finding a different way of doing that, which is more focused on their role in serving the community around them together with others,” said Ms. Ala’i.

Despite efforts by the Iranian authorities to disrupt BIHE’s operation by raiding hundreds of Bahá’í homes and offices associated with it, confiscating study materials, and arresting and imprisoning dozens of lecturers, it has grown significantly over the past three decades. It relies on a variety of knowledgeable individuals both in and outside of Iran to enable youth to study a growing number of topics in the sciences, social sciences, and arts. Overall, not only has BIHE survived thirty years, it has thrived.

Studying at BIHE is not easy. Because it’s not a public university, there is no funding available, and many students hold down full-time jobs. It is common to travel across the country to go to monthly classes in Tehran. Sometimes, students will have to commute from a home on one side of the city to the other in the middle of the day, because these are the only spaces available to hold classes. Despite these logistical challenges, students meet high academic standards.

“I have talked to BIHE students who said when their teacher was arrested and put in jail and all their materials were confiscated, they would get together for class just the same,” said Saleem Vaillancourt, the coordinator of the Education is Not a Crime campaign, which brings attention to the issue of denial of education to the Bahá’í s in Iran. “These students continued studying together, despite the fact that they didn’t have a teacher. This was their attitude, it didn’t seem remarkable to them. They just said this is what we have to do, because they had a commitment to the process.”

Universal education is a core belief of the Bahá’í Faith, and when the authorities in Iran sought to deny Baha’i students this critical and fundamental right, the Bahá’í community pursued a peaceful solution—never for a moment conceding their ideals, never surrendering to their oppressor, and never opposing the government. Instead, for decades, it has been seeking constructive solutions, a show of its longstanding resilience.

In Iran, persecution of the Bahá’ís is official state policy. A 1991 memorandum approved by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei states clearly that Bahá’í s “must be expelled from universities, either in the admission process or during the course of their studies, once it becomes known that they are Baha’is.”

Other forms of persecution torment the Bahá’í s in Iran as well. An open letter dated 6 September 2016 to Iran’s President from the BIC draws his attention to the economic oppression faced by the Bahá’í s there. The letter highlights the stark contradiction between statements espoused by the Iranian government regarding economic justice, equality for all, and reducing unemployment on the one hand, and the unrelenting efforts to impoverish a section of its own citizens on the other.

“The Bahá’í community in Iran wasn’t going to let itself go quietly into the night. It wasn’t going to allow itself to be suffocated in this way,” said Mr. Vaillancourt.

A distinctly non-adversarial approach to oppression fundamentally characterizes the Bahá’í attitude towards social change. The Bahá’í response to oppression draws on a conviction in the oneness of humanity. It recognizes the need for coherence between the spiritual and material dimensions of life. It is based on a long-term perspective characterized by faith, patience, and perseverance. It at once calls for obedience to the law and a commitment to meet hatred and persecution with love and kindness. And, ultimately, this posture has at its very center an emphasis on service to the welfare of one’s fellow human beings.

“I think we see in the world today the breakdown of communities that people would not have thought could happen so easily. We’ve come to realize that living side by side is not enough. We need to live together and know one another, and the best way to know one another is to start working for the betterment of society,” said Ms. Ala’i.

“As the Bahá’ís in Iran have begun to do this in a more conscious way, other Iranians have come to know their Bahá’í neighbors and understand that much of what they had heard about the Bahá’ís from the government and clergy were lies. As they have become more involved in the life of the communities where they live, the Bahá’ís have witnessed an immense change in the attitude of other Iranians towards them.”

The Bahá’í response to oppression is not oppositional and ultimately strives toward higher degrees of unity. Its emphasis is not only on collective action, but on inner transformation.

This strategy is a conscious one employed by the Bahá’í community. Going beyond the tendency to react to oppression, war, or natural disaster with apathy or anger, the Bahá’í response counters inhumanity with patience, deception with truthfulness, cruelty with good will, and keeps its attention on long-term, beneficial, and productive action.

The Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education embodies all of these elements.

“BIHE is an extraordinary achievement,” commented Mr. Vaillancourt. “Perhaps the least known, longest-running, and most successful form of peacefully answering oppression that history has ever seen. It sets the best example I know of for this particular Bahá’í attitude to answering persecution or answering the challenging forces of our time, where we try to have an attitude, posture, and response of constructive resilience.”

Listen to the podcast episode associated with this Bahá’í World News Service story.

It is little known in the West among students and adherents of the Baha’i Faith that Bahá’u’lláh addressed Himself to the public press. It is necessary to set aside squeamishness to depict the circumstances which brought about His doing so. A spring day in Yazd, a Persian city dating from the fifth century, the seat of numerous mosques, an important centre for the production of silk carpets. It was the 19th of May, 1891. Exhilarated by the violence it had witnessed, the excited mob called for the shedding of more blood of the hated Bahá’ís. Only two victims remained, young brothers in their early twenties. Already the crowd had been treated to a thrilling spectacle. A young man of twenty-seven, ‘Ali-Asghar, had been strangled and his body dragged through the streets to the accompaniment of drums and trumpets. Then Mullá Mihdí, a man in his eighty-fifth year, had been beheaded and his corpse hauled in similar manner to another quarter of the city where a considerable throng of onlookers, their frenzy mounting with the music, witnessed the decapitation of Áqá ‘Alí, the youthful brother-in-law of the two young men who had thus far escaped harm. From there the people rushed to yet another sector of Yazd where they relished the sight of Mullá ‘Alíy-i-Sabzivárí having his throat slashed. They then fell upon his body, hacking it to pieces with a spade while he was still alive, and pounded his skull to a pulp with stones. At the moment he was seized he had been addressing the tumultuous gathering, exhorting them to recognize the truth of the New Day, fully aware of his imminent martyrdom and glorying in it. Then, in yet another quarter, the townsfolk rejoiced in slaying Muḥammad-Báqir. It is reasonable to feel compassion far this rabble. Theirs was a profound and manipulable ignorance easily inflamed by fanatical rhetoric and capable, with encouragement from figures of authority, of finding expression in acts of depravity and barbarism. The calculating would be among them—those with vested interests, fearful of loss of power and office—and ruffians and idle thrill-seekers; but no doubt many of their number were utterly convinced that their actions were meritorious in the sight of God, would win the approval of His Prophet and priests, and secure their position in the all-important afterlife. And so their sincere devotion led them to participate in these murders of supposed enemies of the established order. It is a classic example of what scholars of the phenomenon call ‘enantiodromea’, the principle by which any extreme—even virtue—if pushed to the limit, grotesquely crosses over into its opposite.

Five had died. But two young men remained and these were to receive the full force of the crowd’s savage fury. The music grew wilder, drowning the shouts of the swirling mob which propelled the youths brutally to the public square, Maydán-i-Khán, where an especially theatrical fate, matched to the mood of the crowd, awaited them.

The youths, sons of Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Káshání, known as Baktáshí, were silk weavers. They had been raised by affectionate parents and had always lived close to the bosom of their family. Everything about them was conventional for that time and place save that they and their parents had embraced the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh. It was this circumstance which brought them to the horrific scene on that spring day in Yazd. The young men, with the five other Bahá’ís whose deaths they had just witnessed, had gathered for a meeting when a surprise raid was conducted on the house and all were carried off. It is said that some ill-disposed neighbours had alerted the authorities. Good citizens, these, for the pogrom had been instigated by the mujtahid of the city, Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Sabzivárí, acting on instructions of the Governor, Jalalu’d-Dawlih, and the slaughter of the victims—sanctioned sport for the Muslim populace—could be averted only by their denial of faith. The seven were, in a caricature of trial, invited to renounce their religion. How can the true believer barter or dissemble? Having spurned the offer, all seven were condemned to death and surrendered to the executioner and the mob who were eager to aid him in his grisly task.

The elder brother, age twenty-three, bore the same name as his friend who had died earlier that day—‘Alí-Aṣghar. He had recently married and was the father of an infant daughter. The younger, Muḥammad-Ḥasan, age twenty-one, has been described by those who knew him as a youth of extreme beauty, delicacy and masculine grace. The official executioner, Afrasiyab, and the chief constable, Mubárak-Khán, had been urged by the Governor to spare Muḥammad-Ḥasan’s life, if possible, by persuading the young man to recant. Were he to do so, he would be welcomed at the residence of the Governor and showered with favours.

‘Alí-Aṣghar was dealt with first. Having swiftly affirmed his refusal to recant, he was beheaded. Then it was his younger brother’s turn. The Governor’s enticement was extended by the constable to the handsome young man from whom it drew an impatient reply: ‘Hurry up! My friends have all preceded me! Do what you are charged to do!’ He was then decapitated. In a burst of showmanship—playing to the cheering crowd—the executioner slit open the boy’s stomach, plucked out the heart, liver and intestines, and held them aloft. This exhibitionist gesture inspired the audience to commit further atrocities. The head of Muḥammad-Ḥasan was impaled on a spear and paraded through the city—again with the accompaniment of music—and suspended on a mulberry tree. The multitude stoned it so viciously that the skull was broken. His body was then cast before the door of his mother’s house. Some women darted from the crowd, danced into the room where the mother sat, and mocked her. Pieces of the boy’s flesh were carried away to be used as a medicament. Then the head of Muḥammad-Ḥasan was attached to the lower part of his body and borne with the remains of the other martyrs to the outskirts of the city where they were pelted with stones and finally thrown into a pit in the plain of Salsabíl.

The elder brother, ‘Alí-Aṣghar, was not spared ignominy. In an especially cruel gesture, the crowd carried his head to the home of his mother and cast it into the room where she sat with her son’s young wife. The mother arose, bathed her son’s head, and set it outside, admonishing her jeering torturers not to attempt to return to her what she had given to God.

The frenzy had at last reached its climax, and now a carnival atmosphere prevailed. The Governor declared a public holiday and by his order the shops were closed. When evening came the city was illuminated and the populace gave itself over to festivities.

The name of the mother of the two young men has not come down to us; we know her only as Umm-i-Shahíd, the mother of the martyr, though she lost more than one member of her family that day. But the magnificence of her gesture will fire the imagination of generations to come. She lived on into the period of the ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and received from Him at least one Tablet extolling her courage and fortitude, and consoling her in her loss. The young widow of ‘Alí-Aṣghar, Sakinih Sultán, chose not to remarry, though she had offers and was urged to do so. Apprised of her plight, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá invited her and her infant daughter, Fáṭimih Ján, to come to the Holy Land where she had the bounty of serving in His household.

Thus all seven lost their lives. It was not, alas, the only occasion upon which a septet of believers was slain in Yazd; similar episodes occurred in July 1955 and as recently as September 1980. There were also many isolated martyrdoms in that city over the years, and an especially devastating upheaval took place in 1903 when many Bahá’ís lost their lives in various ways, including stabbing and axeing, and one even being shot from a cannon by a direct order of Jalal’ud-Dawlih, the Governor. Bahá’u’lláh stigmatized this man—son of Ẓillu’s-Sulṭán ‘The Infernal Tree’, and grandson of Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh—’The Tyrant of Yazd’.

The deaths of the seven plunged Bahá’u’lláh, then living out the penultimate year of His life in the mansion of Bahjí, into profound grief. The late Hand of the Cause H. M. Balyúzí, in Bahá’u’lláh, the King of Glory, recounts:

When news of the death of the Seven Martyrs of Yazd reached them, it brought great sorrow to Bahá’u’lláh. Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥabíbu’lláh (a great-nephew of the wife of the Báb) writes that for nine days all revelation ceased and no one was admitted into His presence, until on the ninth day they were all summoned. The deep sorrow that surrounded Him . . . was indescribable. He spoke extensively about the Qájárs and their deeds. Afterwards, He mentioned the events of Yazd; thus sternly did the Tongue of Grandeur speak of Jalalu’d-Dawlih and Ẓillu’s-Sulṭán. … Then He said: ‘Do not be sad, do not be downcast, do not let your hearts bleed. The sacred tree of the Cause of God is watered by the blood of the martyrs. A tree, unless watered, does not grow and bear fruit . . .’

Bahá’u’lláh also revealed a Tablet, as yet not fully translated into English, honouring the seven martyrs. Sometimes popularly referred to as the ‘Tablet to The Times’ because of its reference to the most respected and influential newspaper of the day—The Times of London—it is a document of astonishing power. The tone is one of impassioned anguish, the ‘Tongue of Grandeur’ giving divine expression to our human responses, reflecting even our indignation and bewilderment, our sense of outrage and inconsolableness. Specific reference is made to the two young brothers and an unusually full description is given of their torture and martyrdom. The Governor’s offer of protection for the younger man is mentioned and even the sector of the square where the youths died is named. Such atrocities, Baha’u’llah exclaims, have not been witnessed in the past nor will again be seen in future. He describes the mutilating of the bodies, alludes to the reward given to the executioner, the taunting and reviling of the families of the victims, the parading of the head on spear-point through the streets to celebratory musical accompaniment, the lighting of the city by night, the festival air which prevailed. God knows, He laments, what the oppressed innocents suffered.

Then He calls upon the public press of the world—newspapers, in the Bahá’í Revelation are exhorted by Bahá’u’lláh to mirror truth, and all those responsible for their production ‘to be sanctified from malice, passion and prejudice, to be just and fair-minded, to be painstaking in their enquiries, and ascertain all the facts in every situation’—to take note of these happenings, to launch an enquiry, to faithfully record these facts and, in effect, to aid in awakening human consciousness to these sacrifices. The Tablet was not delivered to The Times (nor perhaps was intended to be), but in the following excerpt that newspaper is singled out, it would seem, as representative of the rational spirit of enquiry, of all that is true, praiseworthy and humane in Western thought:

O ‘Times’, O thou endowed with the power of utterance! O dawning place of news! Spend an hour with the oppressed of Irán, and witness how the exemplars of justice and equity are sorely tried beneath the sword of tyrants. Infants have been deprived of milk, and women and children have fallen captive to the lawless. The blood of God’s lovers hath dyed the earth red, and the sighs of His near ones have set the universe ablaze.

O assemblage of rulers, ye are the manifestations of power and might, and the fountainheads of the glory, greatness and authority of God Himself. Gaze upon the plight of the wronged ones. O daysprings of justice, the fierce gales of rancour and hatred have extinguished the lamps of virtue and piety. At dawn, the gentle breeze of divine compassion hath wafted over charred and cast-out bodies, whispering these exalted words: ‘Woe, woe unto you, O people of Irán! Ye have spilled the blood of your own friends and yet remain in ignorance of what ye have done. Should ye become aware of the deeds ye have perpetrated, ye would flee to the desert and bewail your crimes and tyranny.’

O misguided ones, what sin have the little children committed? Hath anyone, in these days, had pity on the dependants of the oppressed? A report hath reached Us that the followers of the Spirit (Christ)—may the peace of God and His mercy be upon Him—secretly sent them provisions and befriended them out of utmost sympathy. We beseech God, the Eternal Truth, to confirm all in accomplishing that which is pleasing to Him.

O newspapers published throughout the cities and countries of the world! Have ye heard the groan of the downtrodden, and have their cries of anguish reached your ears? Or have these remained concealed? It is hoped that ye will investigate the truth of what hath occurred and vindicate it.

In His Ṭarázát, Bahá’u’lláh, Who had, on more than one occasion, been personally slandered and maligned in the press, and His Cause misrepresented in stories fabricated by His avowed enemies, recorded His awareness of inaccurate, perhaps even irresponsible, reporting:

Concerning this Wronged One, most of the things reported in the newspapers are devoid of truth. Fair speech and truthfulness, by reason of their lofty rank and position, are regarded as a sun shining above the horizon of knowledge. The waves rising from this Ocean are apparent before the eyes of the peoples of the world and the effusions of the Pen of wisdom and utterance are manifest everywhere.

It is reported in the press that this Servant hath fled from the land of Ṭá (Ṭihrán) and gone to ‘Iráq. Gracious God! Not even for a single moment hath this Wronged One ever concealed Himself. Rather hath He at all times remained steadfast and conspicuous before the eyes of all men. Never have We retreated, nor shall We ever seek flight. In truth it is the foolish people who flee from Our presence. We left Our home country accompanied by two mounted escorts, representing the two honored governments of Persia and Russia until We arrived in ‘Iráq in the plenitude of glory and power. Praise be to God! The Cause whereof this Wronged One is the Bearer standeth as high as heaven and shineth resplendent as the sun. Concealment hath no access unto this station, nor is there any occasion for fear or silence.

In the same Tablet He extols knowledge and describes the integrity and regard for truth which should govern those who write for newspapers:

Knowledge is one of the wondrous gifts of God. It is incumbent upon everyone to acquire it. Such arts and material means as are now manifest have been achieved by virtue of His knowledge and wisdom which have been revealed in Epistles and Tablets through His Most Exalted Pen—a Pen out of whose treasury pearls of wisdom and utterance and the arts and crafts of the world are brought to light.

In this Day the secrets of the earth are laid bare before the eyes of men. The pages of swiftly-appearing newspapers are indeed the mirror of the world. They reflect the deeds and the pursuits of diverse peoples and kindreds. They both reflect them and make them known. They are a mirror endowed with hearing, sight and speech. This is an amazing and potent phenomenon. However, it behooveth the writers thereof to be purged from the promptings of evil passions and desires and to be attired with the raiment of justice and equity. They should inquire into situations as much as possible and ascertain the facts, then set them down in writing.

Among the indicators that “appear as the outstanding characteristics of a decadent society”, corruption of the press is cited by Shoghi Effendi, together with “the degeneracy of art and music” and the “infection of literature”, in his masterful and succinct analysis in “The Unfoldment of World Civilization”. In that same essay, in sketching the broad outlines of the World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, whose goal is the unification of the planet, he does not fail to mention the lofty and constructive role to be played by a truly free press. “The press will, under such a system,” he writes, “while giving full scope to the expression of the diversified views and convictions of mankind, cease to be mischievously manipulated by vested interests, whether private or public, and will be liberated from the influence of contending governments and peoples.” No “mirror of the world” more dramatically reflects the emergence of the Baha’i Faith from obscurity than the press. With the renewed persecution of the Bahá’ís in the land where the Faith was born—persecution which, despite its instigators’ seeming sole concession to enlightenment in the adoption of polite refinements such as closeted firing squads, private hangings and diabolical, exquisitely designed secret tortures, has the same demonic force and malicious purpose as earlier episodes—the media, and particularly the press of the world, on an unprecedented scale, locally, nationally and internationally, has sympathetically, emphatically, eloquently, insistently and for the most part accurately reported the situation, expressed shock and dismay editorially, striven to alert readers to the gravity of the oppression, condemned its barbarity and demanded its cessation. Among them, it is noted with gratification, is The Times.