Although the 20th century witnessed the increasing recognition of principles such as universal human rights, democratic ideals, the equality of human beings, social justice, the peaceful resolution of conflict, and condemnation of the barbarism of war, it was nevertheless one of the bloodiest centuries in all human history. Such a development was unpredicted by classical sociological theorists writing in the second half of the 19th century, who either did not devote much attention to the question of war and peace or were optimistic about the prospects for peace in the 20th century. While war and peace were central questions in the social theories of both Auguste Comte (1798–1857),1Auguste Comte, Introduction to Positive Philosophy (Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1970). the founder of positivism, and Herbert Spencer (1820–1903),2Herbert Spencer, Evolution of Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967). the founder of evolutionary and synthetic philosophy, for example, both conceived of social change as an evolutionary movement towards progress and characterized the emerging modern society as essentially peaceful—one in which military conquest aimed at the acquisition of land would be replaced with economic and industrial competition.3This is part of Comte’s law of three stages. According to this idea, all societies evolve by going through religious/theological, metaphysical/philosophical, and scientific/positive stages. Spencer defined a military society as one in which the social function of regulation is dominant, while in an industrial society the economic function predominates. Other classical theorists generally assumed that war among nations was a thing of the past.4Contrary to the popular perception, Durkheim, Marx, and Weber rarely engaged in a direct discussion of war or peace. Only after the onset of the World War I did Durkheim, Simmel, and Mead side with their own countries and discuss the issue. Such optimism was partly rooted in the relative security of Europe during the 19th century where, between the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 and the onset of World War I in 1914 there was a relatively long stage of peace, interrupted mainly by the German-French war of 1870. However, this security was a mere illusion, accompanied as it was by increasing militarism and nationalism in Europe and the vast scale of war and genocide perpetrated by European powers in their pursuit of colonial conquest in Africa and other parts of the world.

Standing in contrast to the misplaced optimism of the classical 19th century sociologists is the spiritual figure of Bahá’u’lláh, who was born in 1817 in Persia and initiated a transformative global religion centered on the urgency and necessity of peace making. He perceived that both the institutional structures of the 19th century and their cultural orientation promoted various forms of violence, including international wars. The significance of Bahá’u’lláh and His insights as they apply to peace movements and peace studies is evident through an examination of His worldview and of the manner in which His writings reconstruct foundational concepts such as mysticism, religion, and social order—emphasizing the replacement of the sword with the word.

Bahá’u’lláh and the Removal of the Sword

Mírzá Ḥusayn ‘Alíy-i-Núrí, who took the title Bahá’u’lláh (the Glory of God

), was born in Tehran, Iran, in 1817. As a young man, Bahá’u’lláh accepted the claim of the young merchant from Shiraz known as the Báb (the Gate

) to be the Promised One of Shí‘ih Islam. Both the clerics and state authorities in Iran declared the Báb’s ideas heretical and dangerous and unleashed a systematic campaign of genocide directed at His followers, the Bábís. The Báb Himself was executed in 1850—only six years after the announcement of His mission. While the writings of the Báb provided fresh and innovative interpretations of religious ideas, they pointed to the imminent appearance of a new Manifestation (prophet or messenger) of God and defined His entire revelation as a preparation for the coming of that great spiritual educator. During a massacre of the Bábís in 1852, Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned in a dungeon in Tehran, where He received an epoch-making experience of revelation and perceived Himself to be the Promised One of all religions, including the Bábí Faith. After four months of imprisonment, and the confiscation of all His property, He was exiled to the Ottoman Empire, first to Baghdad, then in 1863 to Constantinople (Istanbul), and from there to Adrianople (Edirne), and finally, in 1868, to the fortress city of ‘Akká in the Holy Land, where He died in 1892.

Although Bahá’u’lláh founded a new religion, the meaning, and particularly the end purpose, of religion is transformed in His writings. As traditionally conceived, religion is often focused on a set of theological doctrines about God, prophets, the next world, and the Day of judgment. While these concepts are discussed and elucidated in His writings, Bahá’u’lláh emphasizes that He has come to renew and revitalize humanity, to reconstruct the world, and to bring peace. In His final work, the Book of the Covenant, He describes the purpose of His life, sufferings, revelation and writings in this way:

The aim of this Wronged One in sustaining woes and tribulations, in revealing the Holy Verses and in demonstrating proofs hath been naught but to quench the flame of hate and enmity, that the horizon of the hearts of men may be illumined with the light of concord and attain real peace and tranquillity.5Bahá’u’lláh, Kitáb-i-‘Ahd (Book of the Covenant), in Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978), 219.

In other words, affirming spiritual principles is inseparable from transforming the social order and from replacing hatred and violence with love and universal peace. From a Bahá’í point of view, then, religion must be the cause of unity and concord among human beings, and if it becomes a cause of enmity and violence, it is better not to have religion.6See for example, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks. Making peace is the essence of Bahá’u’lláh’s normative orientation and worldview. It is ironic, therefore, that both the King of Iran and the Ottoman Sultan rose together against Bahá’u’lláh to silence His voice by intriguing to exile Him to the city of ‘Akká; however, their oppressive decision in the end only exemplified the Hegelian concept of the cunning of Reason,

7Georg W. F. Hegel, Reason in History (New York: Liberal Arts Press, 1953), 25–56. in which Reason realizes its plan through the unintended consequences of actions by individuals whose intent is their own selfish desires. As Bahá’u’lláh has frequently stated, His response to this final exile ordered by these two kings was to publicly announce His message to the rulers of the world. Upon arrival in ‘Akká, He wrote messages to world leaders, including those of Germany, England, Russia, Iran, and France, as well as to the Pope, explicitly declaring His cause and calling them all to unite and bring about world peace. The second irony is that it was through this exile that He was brought to the Holy Land, where the coming of final peace in the world is prophesied to take place, when the wolf and lamb will feed together and swords will be beaten into plowshares.8Isaiah 11:6 and 2:4.

In order to better understand the vital connection between Bahá’u’lláh’s revelation and His concern with peace, let us examine that experience of revelation in the Tehran dungeon in 1852 which marks the birth of the Bahá’í Faith. Bahá’u’lláh describes this experience:

One night, in a dream, these exalted words were heard on every side:

Verily, We shall render Thee victorious by Thyself and by Thy Pen. Grieve Thou not for that which hath befallen Thee, neither be Thou afraid, for Thou art in safety. Erelong will God raise up the treasures of the earth—men who will aid Thee through Thyself and through Thy Name, wherewith God hath revived the hearts of such as have recognized Him.9Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, accessed 7 June 2018, http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/epistle-son-wolf/#f=f2-35

This brief statement epitomizes many of the central teachings of the Bahá’í Faith, one of the most important of which is the replacement of the sword with the word. The victory of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh will take place through the person and character of Bahá’u’lláh and by means of His pen: words and their embodiment in deeds are the only means through which the message of Bahá’u’lláh can be promoted. Thus, the Islamic concept of jihad is abrogated, as is any concept of the religion and its propagation that includes violence, discrimination, coercion, avoidance, and hatred of others. Bahá’u’lláh continually presents the elimination of religious fanaticism, hatred, and violence as one of the main goals of His revelation.

This first experience of revelation defines the substantive message of the new religion in terms of the method of its promotion: A peaceful and dialogical method is the very essence of the new concept of peace and justice. Unlike doctrines that justify forms of violence and oppression as acceptable or even necessary methods of establishing peace and justice in the world, Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings categorically affirm the unity of substance and method in peace making: peace is realized through the way we live, the words we use, and the means we employ to bring about justice, unity, and peace. For Bahá’u’lláh, the time has come to reject the law of the jungle not only in our normative pronouncements about humanity but also in the methods we pursue in order to realize lofty ideals.10See Saiedi, From Oppression to Empowerment,The Journal of Bahá’í Studies 26:1–2 (Spring/Summer 2016), 28–30.

The word, or the pen, is central in Bahá’í philosophy. In the experience of revelation, there is a conversation between God and Bahá’u’lláh, which is an exact repetition of the conversation between God and Moses. According to the Qur’án, God gives two proofs to Moses: His staff and His shining hand. When Moses places His staff on the ground, it becomes a mighty snake, causing Him to become afraid and stand back. God tells Him: Be Thou not afraid, for Thou art in safety.

11Qur’an 28:31. These same words are now uttered by God to Bahá’u’lláh,12While in translation they may appear to be slightly different, they are identical in the original Arabic. implying that the staff of Moses has been replaced by the pen of Bahá’u’lláh as His mighty proof of truth. Likewise, instead of the hand of Moses, the entire being and character of Bahá’u’lláh have become His new evidence. The immediate implication is the unity of Bahá’u’lláh and Moses. This reflects one of Bahá’u’lláh’s central teachings: that all the Manifestations of God are one and that They convey the same fundamental spiritual truth, leading to the principle of the harmony and unity of all religions.

This replacement of the staff with the pen further emphasizes the fact that His cause is rendered victorious through the effect of His words, rather than the performance of supernatural phenomena, or miracles; His message and His teachings constitute the supreme evidence of His truth. This replacement of physical miracles with the miracle of the spirit, namely the Word, is one of the central distinguishing features of Bahá’u’lláh’s worldview. But the most direct expression of the centrality of the pen in Bahá’u’lláh’s revelation is the new definition and conception of the human being offered in this first experience of revelation. The assertion that the cause of Bahá’u’lláh can only be rendered victorious by the pen implies that each soul possesses the capacity to independently recognize spiritual truth. Bahá’u’lláh frequently points out that all humans are created by God as mirrors of divine attributes, and because all individuals are responsible for realizing this divine gift, all the writings of Bahá’u’lláh, in one way or another, call for spiritual autonomy; no one should blindly follow or imitate any other in spiritual, political, and ethical issues. That is why priesthood has been eliminated in the Bahá’í religion and all Bahá’ís are equally and directly responsible before God. The implication of this spiritual autonomy is the utilization of democratic forms of decision making, as characterizes the Bahá’í administrative institutions. However, this form of democracy transcends the materialistic and partisan definition of the prevalent forms in society. Rather, it is a democracy of consultation based on a spiritual definition of reality that views all humans as noble beings endowed with rights.

One final implication of this first experience of revelation needs to be emphasized. According to Bahá’u’lláh’s description, the message of God was brought to Him by a Maid of Heaven. While God, the unknowable, is neither male nor female, the revelation of God through this Word, the supreme sacred reality in the created world, is presented as a feminine reality. Bahá’u’lláh received His revelation not from a tree, a bird, or a male angel, but rather from a female angel who metaphorically symbolizes the inner mystical truth of all the prophets of God. Therefore, the very inception of the Bahá’í revelation is characterized by a fundamental re-examination of the station of women. They are no longer the embodiments and symbols of selfish desires, irrationality, corruption, and worldly attraction; instead, they represent the supreme reflection of God in this world. At the same time, the removal of the sword in this first experience of revelation is a revolutionary critique of patriarchal culture and worldview. These two points are inseparable. The realization of a culture of peace requires the equality and unity of men and women, as violence and patriarchy are inseparable.

From Word Order to World Order

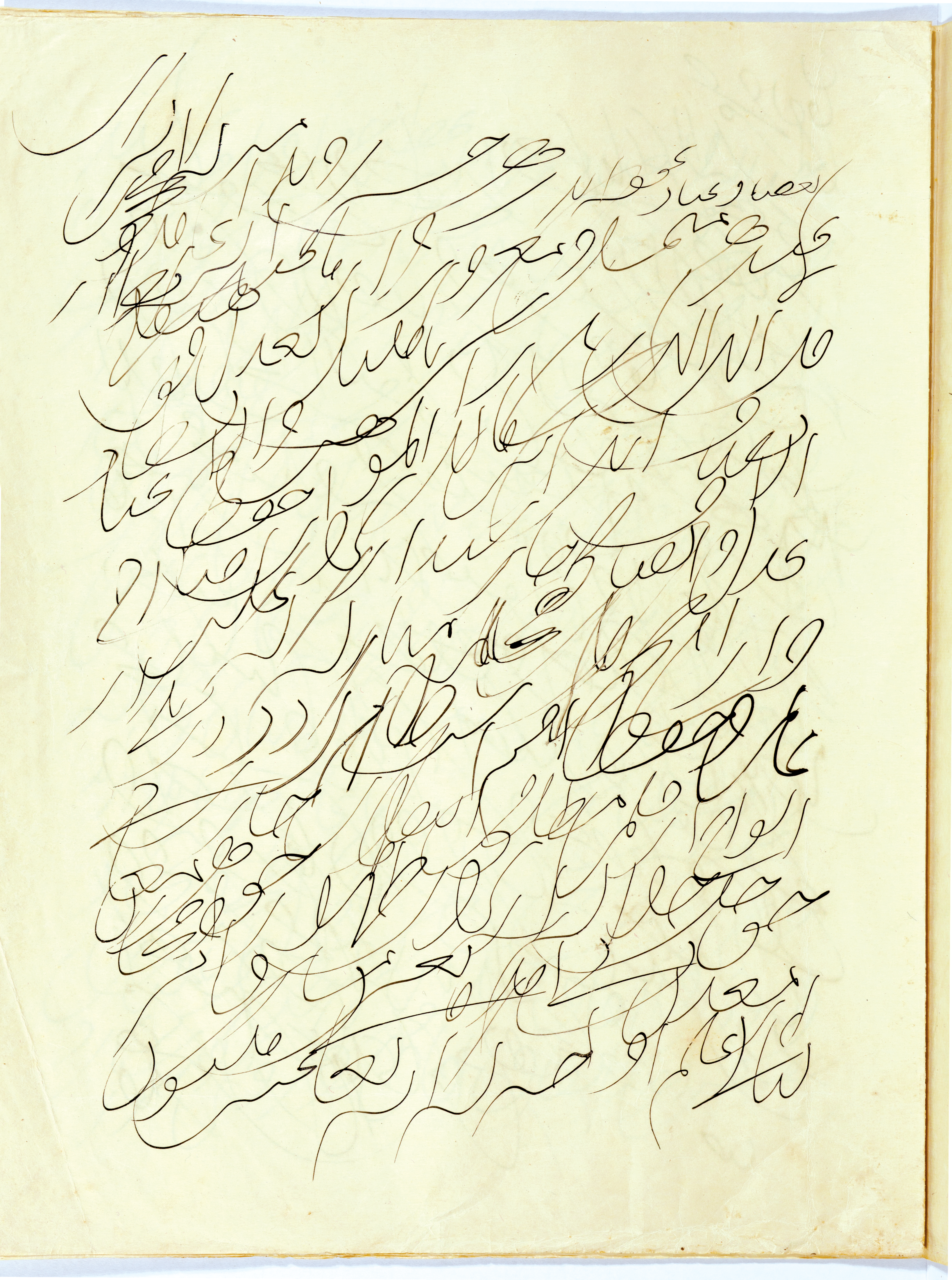

The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh cover a period of forty years, from His imprisonment in the Tehran dungeon in 1852 to His passing in 1892. In the following passage, He describes the purpose and the stages of His writings:

Behold and observe! This is the finger of might by which the heaven of vain imaginings was indeed cleft asunder. Incline thine ear and Hear! This is the call of My Pen which was raised among mystics, then divines, and then kings and rulers.13Bahá’u’lláh, Ishráqát (Tehran: Mu’assisiy-i-Millíy-i-Matbú‘át-i-Amrí, n.d.), 260. Provisional translation.

In the first part of this statement, Bahá’u’lláh presents the contrasting images of the finger of might

and the heaven of vain imaginings

. While the idea of cleaving the moon is attributed to the prophet Muhammad, now Bahá’u’lláh’s pen is rending not only the moon but the entire heaven, which represents the illusions, idle fancies, superstitions, and misconceptions that have erected walls of estrangement between human beings, have enslaved them, and have reduced their culture to the level of the animal. Bahá’u’lláh emphasizes that violence, oppression, and hatred are embodiments of vain imaginings and illusions constructed by human beings. Now, through his pen, He has come to tear away these veils, extinguish the fire of enmity and hatred, and bring people together.

In the second part of this statement, Bahá’u’lláh identifies the stages and order of His words, which were first addressed to mystics, then to divines, and finally to the kings and rulers of the world. His first writings, those written between 1852 and 1859, including the time He lived in Iraq, primarily address mystical concepts and categories.14See The Call of the Divine Beloved: Selected Mystical Works of Bahá’u’lláh (Haifa, Bahá’í World Centre, 2018), https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/call-divine-beloved/. Those of the second stage, encompassing His writings between 1859 and 1867, address the religious leaders and their interpretation of religion. Finally His writings from 1868 on, directed both to the generality of humankind and to the kings and rulers of the world, address social and political questions. Each stage emphasizes a certain principle of Bahá’u’lláh’s worldview, following the sequence of His spiritual logic. The principles corresponding to these stages are as follows: a spiritual interpretation of reality, historical consciousness—even the historicity of the words of God—and global consciousness. The worldview of Bahá’u’lláh is defined by the mutual interdependence of these three principles.

Each stage of the writings of Bahá’u’lláh aims to reinterpret and reconstruct traditional ideas and worldviews. Therefore, the dynamics of His writings can be described by His reconstruction of mysticism, religion, and the social order.

1. Reconstruction of Mysticism

In His earlier writings, Bahá’u’lláh directly engages with Persian and Islamic forms of mysticism; through these and His later writings, He reconstructs mysticism so as to realize its full potential. To understand this point, it is useful to refer to the twin concepts of the arc of descent (qaws-i-nuzúl) and arc of ascent (qaws-i-ṣu‘úd) which comprise the spiritual or mystical journey. The arc of descent is normally perceived as the descent of reality from God—the dynamics of material creation, culminating in the emergence of human life. As a consequence, however, human beings are estranged from their origin and their own truth, which is the unity of God. This yearning for reunion, in turn, initiates the arc of ascent, the mystical journey of the soul’s return to its source. The arc of ascent, as seen, for example, in the Seven Valleys, transcends the realm of conflict and plurality to discover the underlying truth of all reality, namely God.15 The stages of spiritual ascent are frequently referred to as seven valleys or seven cities. In ‘Aṭṭár’s Conference of the Birds these stages are: search/quest, love, knowledge, contentment/independence, unity, wonderment/bewilderment, and annihilation in God. Baha’u’llah’s Seven Valleys employs these stages, but He makes a slight change in the order, bringing contentment/independence after unity. See The Call of the Divine Beloved. With the annihilation of self that is found in this unity, one is assumed to have reached the zenith of the arc of ascent.

Although in traditional views of mystical consciousness, the zenith of the arc of ascent is the highest and end point of the spiritual journey, in reality this is just the beginning of a new stage. But in traditional consciousness all humans become sacred and equal only in God. In other words, only when living human beings, made of flesh and blood, are divested of their various determinations and turned into an abstraction do they become noble and sacred. For example, only when women are no longer women—that is, when their concrete determinations are negated and annulled in God—do they become equal to men. But concrete, living women remain inferior to men in rights, spiritual station, and rank. Thus despite the claim to see God in everything, the presence of social inequalities including slavery, patriarchy, religious discrimination, political despotism, and caste-like distinctions could go unchallenged.

For that reason, we need a further arc of descent

to bring the fundamental insight and achievement of mystic oneness down to earth. In other words, after tracing the arc of ascent and attaining the consciousness of unity, one must be able to descend once again into the world of concrete plurality and time and maintain the consciousness of unity without being imprisoned in the consciousness of conflict and estrangement. In this way, the wayfarer is transformed into a new being who sees the unity of all in the concrete diversity of the world; in this arc of descent, one comes to see in all people their truth, or their divine attributes. The result of this consciousness is the end of the logic of separation, discrimination, prejudice, and hatred, and the beginning of the culture of the oneness of the human race, encompassing equal rights of all humans, the equality of men and women, religious tolerance and unity, and universal love for all people. Thus, according to Bahá’u’lláh, the real task of the mystic is not just the inward transformation of the annihilation of self in God but to transform the world so that the mystical truth of all human beings is manifested in the relations, structures, and institutions of social order. Since all beings become reflections of God, God and his unity are recognized within the diversity of moments and beings, resulting in the worldview of unity in diversity.

2. Reconstruction of Religion

The reconstruction of religion is, in fact, the first stage of the new arc of descent. In this first step, one descends from the unity of God and eternity to the diversity of the prophets and Manifestations of God. Here, history reveals a unity in diversity that reflects in its dynamics the unity of God: the Bahá’í view finds all the Manifestations of God to be one and the same, because they are reflections of divine unity and divine attributes. Since God is defined in the Torah, Gospel, and Qur’án as being the First and the Last, all the Manifestations are also the first and the last.16Examples are Isaiah 44:6 and 48:12, Revelation 1:8 and 22:13, and Qur’án 57:2. They are also the return of each other. Bahá’u’lláh views the realm of religion as the reflection of both diversity (of historical progress) and unity (of all the prophets). He says:

It is clear and evident to thee that all the Prophets are the Temples of the Cause of God, Who have appeared clothed in divers attire. If thou wilt observe with discriminating eyes, thou wilt behold Them all abiding in the same tabernacle, soaring in the same heaven, seated upon the same throne, uttering the same speech, and proclaiming the same Faith. Such is the unity of those Essences of Being, those Luminaries of infinite and immeasurable splendor! Wherefore, should one of these Manifestations of Holiness proclaim saying:

I am the return of all the Prophets,He, verily, speaketh the truth. In like manner, in every subsequent Revelation, the return of the former Revelation is a fact, the truth of which is firmly established.17Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-i-Iqán: The Book of Certitude (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1983), 153–54.

In other words, the Word of God, which is the essence of all religions, is a living and dynamic reality. It is one Word that, at different historical moments, appears in new forms. The different prophets are like the same sun that appears at different times at a different place on the horizon. While the traditional approach to religion usually reduces the identity of the sun to its historically specific horizon and therefore emphasizes opposition and hostility among various religions, Bahá’u’lláh identifies the truth of all religions as one and calls for the unity of religions. In Bahá’u’lláh’s view, a major cause of violence, war, and oppression in the world is religious fanaticism created by the vain imaginings of religious leaders. He warned: Religious fanaticism and hatred are a world-devouring fire whose violence none can quench. The Hand of Divine power can, alone, deliver mankind from this desolating affliction.

18Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, accessed 8 June 2018, http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/epistle-son-wolf/#f=f2-19. The establishment of peace, then, requires overcoming such religious hatred and discord.

3. Reconstruction of the World

The second step of the new arc of descent relates to the wayfarer’s descent into the world. Here, the consciousness of unity necessarily leads to the principle of the oneness of humankind as well as to universal peace. In traditional religious consciousness, the relationship between the created and the Creator is repeated in all forms of social relations. Thus, the relation between men and women, kings and subjects, free persons and slaves, believers and non-believers, and even clerics and laymen repeat the relation between God and human beings. In this way, the illusion is created that domination, discrimination, violence, and opposition are legitimized by religion. In contrast, Bahá’u’lláh explains that the relation that truly obtains is that because all are created by God and are servants of God, all are equal. Instead of repeating in the realm of social order the relation of God to the created world, the servitude of all before God denotes the equality and nobility of all human beings. The task of true mysticism therefore is not to escape from the world, but rather to transform it so that it becomes a mirror of the republic of spirit or the kingdom of God. Bahá’u’lláh’s global consciousness and His concept of peace are embodiments of this reinterpretation of the world and social order, as reflected in the following statement in which He redefines what it is to be human:

That one indeed is a man who, today, dedicateth himself to the service of the entire human race. The Great Being saith: Blessed and happy is he that ariseth to promote the best interests of the peoples and kindreds of the earth. In another passage He hath proclaimed: It is not for him to pride himself who loveth his own country, but rather for him who loveth the whole world. The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.19Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Maqṣúd (Tablet of Maqṣúd), Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, 167.

The purpose of Bahá’u’lláh’s reinterpretation of mysticism, religion, and social order is to bring about a culture of unity in diversity and to institutionalize universal peace in the world. To discuss His specific concept of peace, it is necessary first to review the existing theories of peace in the social sciences and then identify the structure of Bahá’u’lláh’s vision.

Main Theories of Peace

With the outbreak of World War I, most social theorists took the side of their own country in the conflict and, in some cases, glorified war. Georg Simmel identifies war as an absolute situation

in which ordinary, selfish preoccupations of individuals living in an impersonal economy are placed in an ultimate life-and-death situation. Thus, he concludes, war liberates the moral impulse from the boredom of routine life and makes individuals willing to sacrifice their lives for the good of society.20Georg Simmel, Der Krieg und die Geistigen Entscheidungen (Munich: Duncker and Humblot, 1917). On the other side, Durkheim and Mead both take strong positions against Germany. Discussing Treitschke’s worship of war and German superiority, Durkheim writes of a German mentality

which led to the militaristic politics of that country.21Emile Durkheim, L’ Allemagne au-dessus de Tout: La Mentalité Allemande et la Guerre (Paris: Colin, 1915). Emile Durkheim, L’ Allemagne au-dessus de Tout: La Mentalité Allemande et la Guerre (Paris: Colin, 1915). A similar analysis is found in the writings of Mead, who contrasts German militaristic politics with Allied liberal constitutions. In a distorted and inaccurate presentation of Kant’s distinction between the realm of appearances and the things in themselves, Mead argues that in Kantian theory, the substantive determination of practical life is left in the hands of military elites. Such a state could by definition only rest upon force. Militarism became the necessary form of its life.

22G. H. Mead, Immanuel Kant on Peace and Democracy in Self, War & Society: George Herbert Mead’s Macrosociology. Ed. Mary Jo Deegan (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2008), 159–74. However, modern social scientific literature in general and peace studies in particular offer various theories in regard to war and peace, four of which are particularly significant: realism, democratic peace theory, Marxist theory, and social constructivism and cultural theory.

1. Realism

Realism, the dominant theory in the field of international relations, is rooted in a Machiavellian and Hobbesian conception of human beings. According to this model, states are the main actors in international relations. However, the main determinant of a state’s decision to engage in war or peace is the international political and military structure. This structure, however, is none other than international anarchy; the Hobbesian state of nature is the dominant reality at the level of international relations, since there is no binding global law or authority in the world. In this situation, states are left in a situation necessitating self-help, with each regarding all others as potential or actual threats to its security. Thus, arms races and militarism are rational strategies for safeguarding national security. States must act in rational and pragmatic ways and must not be bound by either internal politics or moral principles in determining their policies. In this situation, war is a normal result of the structure of international relations. According to some advocates of this theory, the existence of nuclear weapons and a bi-polar military structure (as seen in the Cold War) are, paradoxically, conducive to peace.23See, for example, John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: Norton, 2001).

2. Democratic Peace Theory

One of the most well-known theories in relation to war and peace is a liberal theory according to which democracies rarely—if ever—engage in war with each other. This doctrine was first advanced in 1875 by Immanuel Kant in his historic work Perpetual Peace.24Immanuel Kant, Perpetual Peace (New York: Columbia University Press, 1939). In contrast to realism, democratic peace theory sees the root cause of war or peace in the internal political structure of societies. Empirical tests have confirmed the existence of a significant positive correlation between democracy and peace,25See Bruce Russet and John R. Oneal, Triangulating Peace: Democracy, Interdependence, and the International Organizations (New York: W. W. Norton, 2001). with two sets of explanations offered. Institutional explanations emphasize the existence of systematic restraining forces in democracies. The vote of the people matters in democracies, and therefore war is less likely to occur because it is the people rather than the rulers who will pay the ultimate price of war. Cultural explanations argue that democracies respect other democracies and are therefore more willing to engage in the peaceful resolution of conflicts. The internal habit of the democratic resolution of conflicts is said to be extended to the realm of foreign relations.26Among classical social theorists there is considerable sympathy for this theory. Durkheim, Mead, and Veblen all identified the cause of World War I as the undemocratic culture and politics of Germany and Japan. Similarly, Spencer finds political democracy compatible with peace.

3. Marxist Theory

Marxist theory can be discussed in terms of three issues: the relation of capitalism to war or peace, the role of violence in transition from capitalism to communism, and the impact of colonialism on the development of colonized societies. The dominant Marxist views on these issues are usually at odds with Marx’s own positions.

Marx did not address the issue of war and peace extensively. He shared the 19th century’s optimism about the outdated character of interstate wars. In fact, he mostly believed that capitalism benefits from peace and considered Napoleon’s wars a product of that ruler’s obsession with fame and glory.27Karl Marx, The Holy Family (Moscow: Foreign Language Pub. House, 1956), Ch. 6. As Mann argues, Marx saw capitalism as a transnational system and therefore regarded it as a cause of peace rather than war.28Michael Mann, War and Social Theory: Into Battle with Classes, Nations and States, in The Sociology of War and Peace, ed. Colin Creighton and Martin Shaw (Dobbs Ferry: Sheridan House, 1987). He believed that violence is mostly necessary for revolution but affirmed the possibility of peaceful transition to socialism in the most developed capitalist societies. Furthermore, Marx saw the colonization of non-European societies as mostly beneficial for the development of non-European stagnant societies, which in turn would lead to socialist revolutions. In the midst of World War I, Lenin (1870–1924) radically changed the Marxist theory of war and peace, arguing that imperialism or the competition for colonial conquest necessarily causes wars among Western capitalist states. According to Lenin, these wars would destroy capitalism and lead to the triumph of socialism. In his view, violence was the only possible way of attaining socialism.29Vladimir I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (New York: International Publishers, 1939).

Marxist theory has inspired many sociological theories of war and peace, from C. Wright Mills’s thesis of the military-industrial complex to Wallerstein’s theory of the world capitalist system.30See C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956) and Immanuel M. Wallerstein, The Politics of the World-Economy: The States, the Movements, and the Civilizations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984). However, in general, most socialist theories see the root cause of war in the extremes of social inequality. Socialism, therefore, is perceived to be the economic order conducive to peace.

4. Social Constructivism and Cultural Theory

A sociological perspective that has influenced the field of international relations is the theory of social constructivism, which systematically criticizes the realist perspective. Emphasizing the symbolic and interpretive character of social relations and practices, this model, which is influenced by symbolic interactionism, states that war is a product of our socially constructed interpretations of ourselves and others. Mead’s emphasis on the social and interactive construction of self is compatible with a host of philosophical and sociological theories that have emphasized the significance of language in defining human reality. Unlike utilitarian and rationalist theories that perceive humans as selfish and competitive, the linguistic turn emphasizes the social and cooperative nature of human beings. Since being with others is the very constitutive element of human consciousness and self, the realization of peace requires a new social interpretive construction of reality.31See, for example, Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Cultural theories emphasize the causal significance of the culture of violence or peace as the main determinant of war or peace. John Mueller argues that prior to the 20th century, war was perceived as a natural, moral, and rational phenomenon.32John E. Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War (New York: Basic Book, 1989). However, through the First and Second World Wars, this culture changed. According to Mueller, the Western world is moving increasingly in this direction, with the non-Western world lagging behind, although the future is bright since we are moving towards a culture of peace.

Bahá’u’lláh’s Approach to Peace

After World War II and the rise of studies focusing on peace as a scholarly object of analysis, authors such as Johan Galtung distinguished between negative and positive definitions of peace, arguing that negative peace

is both unstable and illusory, while positive peace

is true peace.33Johan Galtung, Peace by Peaceful Means (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1996). This preference for the positive definition provided the vision of a different theory of peace. According to the negative definition, war is a positive and objective reality, while peace simply refers to the absence of war and conflict. The positive definition of peace, on the other hand, views peace as an objective state of social reality defined by a form of reciprocal and harmonious relations that fosters mutual development and communication among individuals and groups. In this sense, war and violence indicate the absence of positive peace. Thus, even when there is no direct coercion and armed conflict, a state of war and aggression may still exist.34Concepts like structural, symbolic, and cultural violence are a few expressions of this new conception of the positive definition of peace.

It is interesting to note that both Bahá’u’lláh and His successor ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (1844–1921) systematically and consistently advocate a unique positive definition of peace. Even the word that Bahá’u’lláh uses about the purpose of His revelation (iṣláh) means both reform or reconstruction and peace making. In many of his writings He calls for ‘imár (development) and iṣláh (peace making/reform/reconstruction) of the world.35Shoghi Effendi has translated isláh as security and peace, betterment, ennoblement, reconstruction, and improvement. Similarly , he has translated ‘imár as reconstruction, revival, and advancement. Thus, for Bahá’u’lláh, the realization of peace involves simultaneously a reform, reconstruction, and development of the institutions and structures of the world; mere desire is not a sufficient condition for the realization of a true and lasting peace, which requires a fundamental transformation in all aspects of human existence. While none of the existing theories provides an adequate path towards peace, each pointing only to aspects of the complex question of war and peace, Bahá’u’lláh’s multi-dimensional, positive approach encompasses all the factors addressed by different contemporary theories. The most explicit expression of this is found in His addresses to the leaders of the world, the Súrih of the Temple (Súriy-i-Haykal).36See The Summons of the Lord of Hosts: Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2010). https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/summons-lord-hosts/

In 1868, in response to His exile to ‘Akká, Bahá’u’lláh wrote individual messages to a number of world leaders, which comprise different parts of the Súrih of the Temple. Although this work constitutes a universal announcement of His revelation, the main message is His call to universal peace. From this call, we see that the real insight offered by the realist theory of peace is not its pessimism regarding the inevitability of war but rather its linking of war with the lack of collective security. In the Súrih of the Temple, Bahá’u’lláh consistently calls for a global approach to peace and the institutionalization of global collective security as a necessary means of realizing peace. Similarly, the concerns addressed in democratic peace theory are also valid, and, although Bahá’u’lláh’s concept of democracy is far more complex than existing definitions and practices, in the Súrih of the Temple He praises democracy as a necessary element for the realization of peace. Impediments to peace such as social inequality, identified in Marxist/socialist theories, are also addressed in this Tablet, which calls for social justice and the elimination of poverty, and points to the arms race as a main cause of social inequality and poverty in the world. Finally, the contribution of the cultural theory in pointing to the need for a culture of peace should be acknowledged; however, such a culture should not be confused with mere consensus regarding the necessity of peace. Rather, in the Súrih of the Temple Bahá’u’lláh calls for a culture of peace based on a new definition of identity, a rejection of patriarchy, and the elimination of all kinds of prejudice.

Bahá’u’lláh sees lasting peace as a multidimensional structure of social relations that includes a culture of peace, democracy, collective security, and social justice, among other elements. These are not random variables or opposed concepts; rather, for Bahá’u’lláh all four are inseparable, interdependent, and harmonious expressions of His spiritual definition of human reality.

The Súrih of the Temple begins with a discussion of the human being as a sacred temple of God. According to Bahá’u’lláh’s writings, humans were created to exist in a state of cooperation, unity, and peace. The brutish culture of war and hatred is opposed to the reality of human beings, who are mirrors of God and reflect divine attributes; all are the thrones of God, created by the same Fashioner, brought into existence through the same creative divine Word and endowed with spiritual potentialities. That is why Bahá’u’lláh consistently calls the world the common home of all peoples and defines a human being as one who, today, dedicateth himself to the service of the entire human race.

37Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Maqṣúd (Tablet of Maqṣúd), Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, 167. This spiritual definition of humanity is centered on the rejection of the law of the jungle and the reduction of humans to that level. In the Tablet of Wisdom, Bahá’u’lláh says that humans are not created for enmity and hatred but rather for solidarity and cooperation. From this philosophical principle He deduces the necessity of a new definition of honor, in which true honor is associated with serving and loving the entire human race:

O ye beloved of the Lord! Commit not that which defileth the limpid stream of love or destroyeth the sweet fragrance of friendship. By the righteousness of the Lord! Ye were created to show love one to another and not perversity and rancour. Take pride not in love for yourselves but in love for your fellow-creatures. Glory not in love for your country, but in love for all mankind.38Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Hikmat (Tablet of Wisdom), Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, 138, para 5.

This spiritual definition of human beings is equated with the true meaning of freedom. Explaining Bahá’u’lláh’s message, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá identifies true freedom as overcoming the logic of the struggle for existence. The time has come for humans to appear as human beings and not as beasts:

And among the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh is man’s freedom, that through the ideal Power he should be free and emancipated from the captivity of the world of nature; for as long as man is captive to nature he is a ferocious animal, as the struggle for existence is one of the exigencies of the world of nature. This matter of the struggle for existence is the fountain-head of all calamities and is the supreme affliction.39‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1997), 316, #227, para 20.

It is obvious that a culture of peace is a necessary reflection of Bahá’u’lláh’s definition of human beings. In this culture, identities are defined in terms of the reciprocal interdependence of human beings rather than contrast or opposition. Such a definition is based upon the Bahá’í concept of unity in diversity, perhaps the most well-known expression of which is Bahá’u’lláh’s aphorism:

O well-beloved ones! The tabernacle of unity hath been raised; regard ye not one another as strangers. Ye are the fruits of one tree, and the leaves of one branch.40Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Mánikc̲h̲í Ṣáḥib (Tablet to Mánikc̲h̲í Ṣáḥib), The Tabernacle of Unity: Bahá’u’lláh’s Responses to Mánikc̲h̲í Ṣáḥib and Other Writings (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2006), 9, para 1.15.

It should be noted that in the above statement unity is not opposed to plurality but rather to estrangement. For Bahá’u’lláh, unity is unity in diversity. Like a tree, the human family consists of various fruits and leaves, but all belong to the same spiritual tree. In the original Persian, unity is yigánigí, and estrangement is bígánigí, its literal opposite. Therefore, a culture of peace is opposed both to a repressive negation of plurality and diversity and to an alienating concept of plurality that sees no possibility of communication, interdependence, and unity among the diverse units of social reality. The Bahá’í concept of unity affirms the diversity of communication but not a diversity of mutual alienation and estrangement.

In this new culture of peace called for in the Súrih of the Temple, a central component is the rejection of the violent culture of patriarchy. At the beginning of the Súrih, Bahá’u’lláh describes His first experience of revelation through the medium of the Maid of Heaven. As previously discussed, this means that the highest spiritual reality, the truth of all the Manifestations, is presented as a feminine reality:

While engulfed in tribulations I heard a most wondrous, a most sweet voice, calling above My head. Turning My face, I beheld a Maiden—the embodiment of the remembrance of the name of My Lord—suspended in the air before Me. So rejoiced was she in her very soul that her countenance shone with the ornament of the good pleasure of God, and her cheeks glowed with the brightness of the All-Merciful. Betwixt earth and heaven she was raising a call which captivated the hearts and minds of men. She was imparting to both My inward and outer being tidings which rejoiced My soul, and the souls of God’s honoured servants. Pointing with her finger unto My head, she addressed all who are in heaven and all who are on earth, saying: By God! This is the Best-Beloved of the worlds, and yet ye comprehend not.41Bahá’u’lláh, Súriy-i-Haykal (Súrih of the Temple), Summons of the Lord of Hosts, 5, para 6.

But if a culture of peace is the logical expression of Bahá’u’lláh’s spiritual definition of the human being, His praise of democracy is another organic expression of His spiritual worldview. As discussed earlier, Bahá’u’lláh’s understanding of humans as spiritual and rational beings is the reason for the replacement of the sword by the word. But His emphasis on the spiritual duty of each individual to think and search independently after truth is accompanied by His affirmation of the unity of all human beings. A natural consequence is His praise of consultation. For Bahá’u’lláh, both individuals’ independent thought and their spiritual unity are realized through the imperative of consultation. His statement, For everything there is and will continue to be a station of perfection and maturity. The maturity of the gift of understanding (khirad) is made manifest through consultation,

42Bahá’u’lláh, from a Tablet translated from the Persian, in Consultation: A Compilation, Prepared by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (February 1978, rev. November 1990), 3. http://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/compilations/consultation/. The word khirad, rendered as gift of understanding in English, is, literally, reason. ndicates that consultation reflects the maturation and realization of human spiritual powers. The wider the expanse of consultation, the greater the likelihood of attaining truth. Democracy is a natural expression of this principle. In the Súrih of the Temple, addressing the Queen of England (the only sovereign of a democratic nation who was addressed by Bahá’u’lláh), He praises both parliamentary democracy and the outlawing of the slave trade:

We have been informed that thou hast forbidden the trading in slaves, both men and women. This, verily, is what God hath enjoined in this wondrous Revelation. God hath, truly, destined a reward for thee, because of this…

…We have also heard that thou hast entrusted the reins of counsel into the hands of the representatives of the people. Thou, indeed, hast done well, for thereby the foundations of the edifice of thine affairs will be strengthened, and the hearts of all that are beneath thy shadow, whether high or low, will be tranquilized.43Bahá’u’lláh, Súriy-i-Haykal (Súrih of the Temple), Summons of the Lord of Hosts, 89–90, paras 172–73.

Bahá’u’lláh’s rejection of slavery and His call for political democracy are inseparable expressions of the same spiritual definition of human beings, but His concept of democracy is far more complex than current approaches. First, He extends democracy not only to the level of nation states but also to international relations. His concept of collective security is an expression of His concept of global consultation and democratic subjugation of the law of the struggle for existence at the level of international relations. Second, He sees democracy as the art of consultation and not a constant war of domination, dehumanization, insult, and enmity among contending parties who are never willing to engage in consultation with one another.

This spiritual definition of human beings and the consequent rejection of the struggle for existence as a legitimate regulating principle of human relations necessarily calls for a system of collective security and for transcendence over a militaristic and animalistic culture of mutual estrangement. But this same definition of humans as noble beings is inseparable from the imperative of social and economic justice. While both pure communism and pure capitalism reduce humans to the level of the jungle and eliminate human freedom, social and economic justice are compatible with a culture of peace, democratic order, and collective security. In the Súrih of the Temple, Bahá’u’lláh calls for both an end to the arms race and movement towards economic justice as preconditions of a lasting peace:

O kings of the earth! We see you increasing every year your expenditures, and laying the burden thereof on your subjects. This, verily, is wholly and grossly unjust. Fear the sighs and tears of this Wronged One, and lay not excessive burdens on your peoples. Do not rob them to rear palaces for yourselves; nay rather choose for them that which ye choose for yourselves. Thus We unfold to your eyes that which profiteth you, if ye but perceive. Your people are your treasures. Beware lest your rule violate the commandments of God, and ye deliver your wards to the hands of the robber. By them ye rule, by their means ye subsist, by their aid ye conquer. Yet, how disdainfully ye look upon them! How strange, how very strange!

… Be united, O kings of the earth, for thereby will the tempest of discord be stilled amongst you, and your peoples find rest, if ye be of them that comprehend. Should any one among you take up arms against another, rise ye all against him, for this is naught but manifest justice.44Bahá’u’lláh, Súriy-i-Haykal (Súrih of the Temple), Summons of the Lord of Hosts, 93–94, paras 179 and 182.

Thus, in Bahá’u’lláh’s worldview, humanity has arrived at a new stage in its historical development, one that is defined by the realization of the unity in diversity of the entire world—the manifestation of the spiritual truth of all human beings. While the modern global cultural turn towards the appreciation of peace is often understood as a product of the revolt against religion and spirituality, the opposite is, in fact, true. As recent postmodern and relativistic philosophies have made clear, a materialistic philosophy is most compatible either with relativity of values or affirmation of the law of nature, namely the struggle for existence. In contrast, a noble conception of all human beings and the affirmation of their equal rights are based upon a spiritual understanding of human reality. In the writings of Bahá’u’lláh, a reconstructed mystical and spiritual consciousness is the necessary foundation of the twin principles of the oneness of humankind and universal peace.

Today, Bahá’ís commemorate the Day of the Covenant, a day dedicated to the remembrance of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s unique station in Bahá’í history. A century after the end of World War I—the bloodiest conflict humanity had ever known until then—today’s remembrance also harks back to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s urgent efforts to promote peace in the years preceding the war, His critical actions to ease suffering during the crisis, and the relevance of His call for peace today.

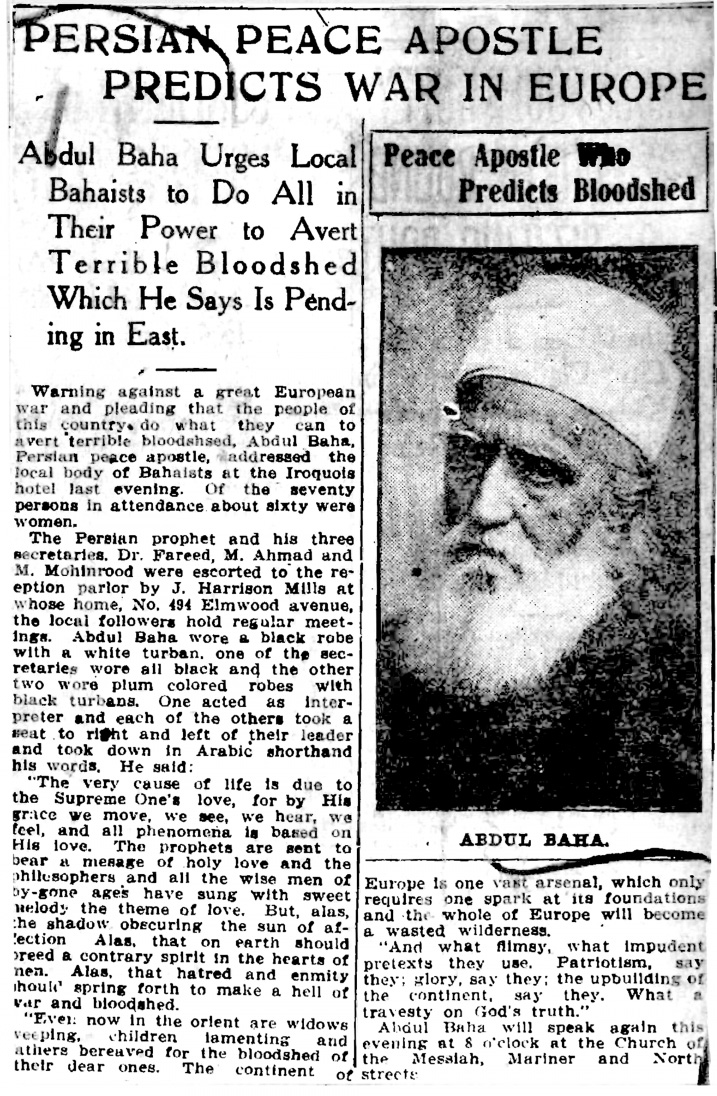

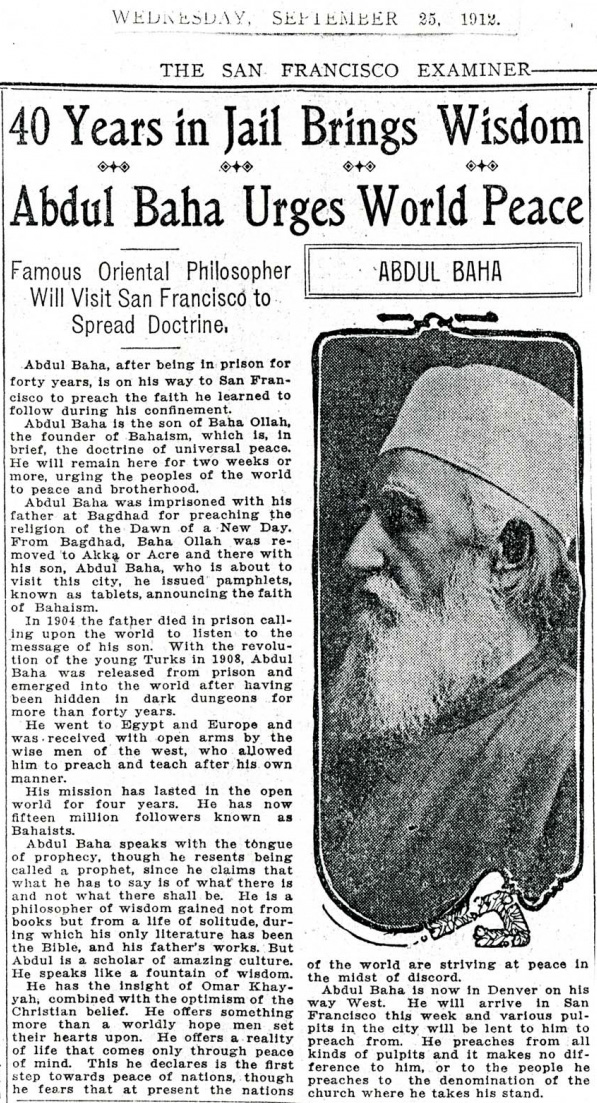

During His tour of Europe and North America from 1911 to 1913, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá often described Europe as on the brink of war. “The time is two years hence, when only a spark will set aflame the whole of Europe,” He said in an October 1912 talk. “By 1917 kingdoms will fall and cataclysms will rock the earth.”

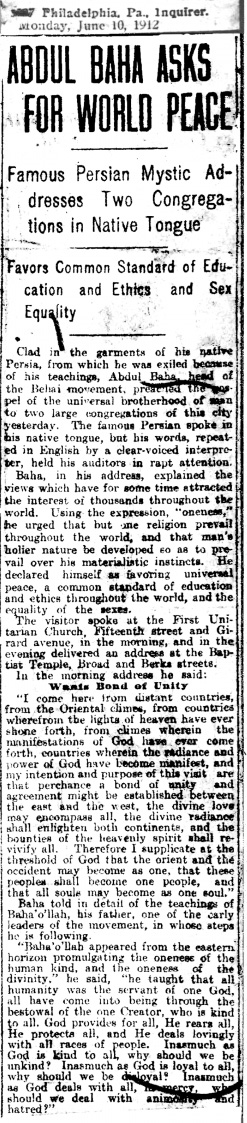

Newspaper reports of His talks highlighted His warnings to humanity of an impending war and the urgent need to unify:

- “The Time Has Come, He Says, for Humanity to Hoist the Standard of the Oneness of the Human World…” –The New York Times, 21 April 1912

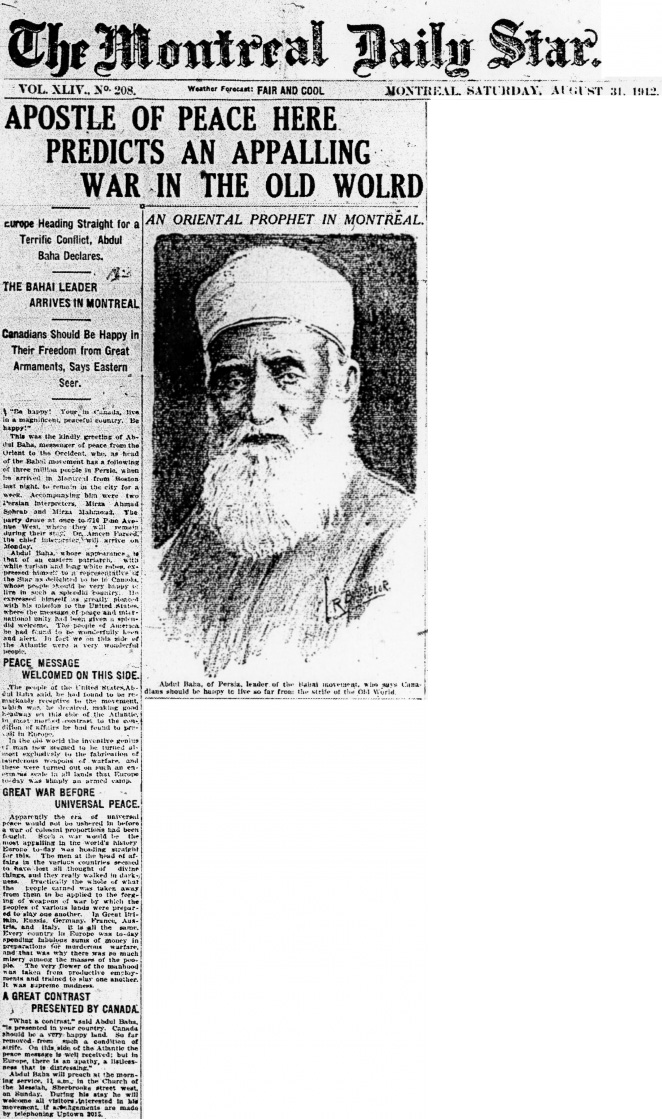

- “APOSTLE OF PEACE HERE, PREDICTS AN APPALLING WAR IN THE OLD WORLD” –The Montreal Daily Star, 31 August 1912

- “PERSIAN PEACE APOSTLE PREDICTS WAR IN EUROPE” –Buffalo Courier, 11 September 1912

- “Abdul Baha Urges World Peace” –The San Francisco Examiner, 25 September 1912

In July 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and the Great War began.

Noting the significance that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gave to the issue of peace, Century of Light, a publication commissioned in 2001 by the Universal House of Justice, states: “From the beginning, ‘Abdu’l Bahá took keen interest in efforts to bring into existence a new international order. It is significant, for example, that His early public references in North America to the purpose of His visit there placed particular emphasis on the invitation of the organizing committee of the Lake Mohonk Peace Conference for Him to address this international gathering…. Beyond this, the list of influential persons with whom the Master spent patient hours in both North America and Europe—particularly individuals struggling to promote the goal of world peace and humanitarianism—reflects His awareness of the responsibility the Cause has to humanity at large.”

Having raised the warning and urged the world to work for peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá returned on 5 December 1913 to Haifa, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Aware of the coming war, He took steps to protect the Bahá’í community under His stewardship and to avert a famine in the region. One of His first decisions upon returning to the Holy Land was to send home all the Bahá’ís who were visiting from abroad.

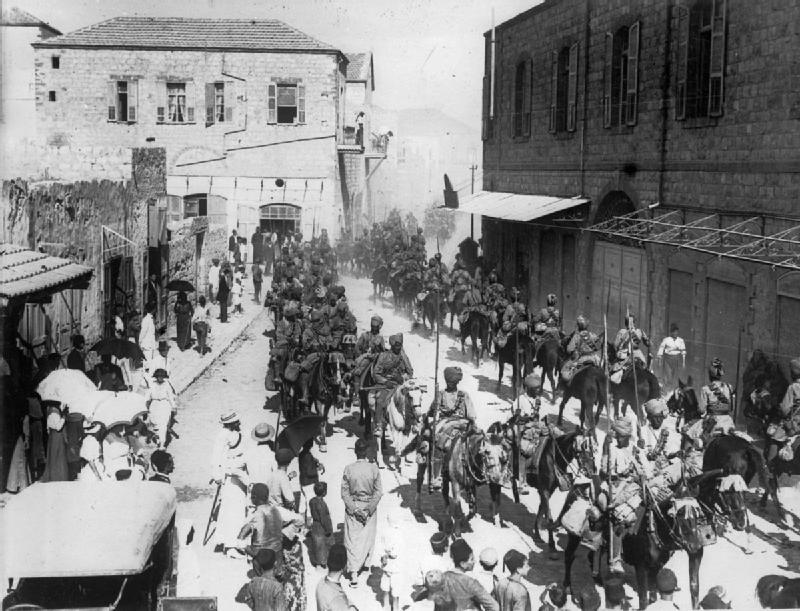

Less than a year later, war broke out in Europe. As the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary, the Allied Powers—including France, Britain, and eventually the United States—formed a strict blockade around Haifa. Communication and travel in and out of the area were almost impossible. Haifa and Akka were swept into the hysteria of war.

To protect the resident Bahá’ís of Haifa and Akka from danger, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá decided to move them to a nearby Druze village called Abu-Sinan, while He remained in Akka with only one other Bahá’í. However, bombardment by the Allied forces necessitated that He eventually join the other Bahá’ís in the village; at one point, a shell landed, but did not explode, in the Ridvan Garden near Akka. ‘Abdu’l Baha had the Bahá’ís in Abu-Sinan establish a dispensary and a small school for the area’s children.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá also intensified efforts to protect the surrounding populations. He directed Bahá’í farmers in the Jordan River Valley to increase their harvest yields and store extra grain in anticipation of a future shortage. After the war broke out and food supplies became scarce, He ensured that wheat would be distributed throughout the region. In July 1917, for example, He visited one farm in Adasiyyih, in present-day Jordan, for 15 days during the wheat and barley harvest. He had the surplus carried by camel to the famine-stricken Akka-Haifa area.

Throughout His ministry as the head of the Bahá’í Faith, from Bahá’u’lláh’s ascension in 1892 to His own passing in 1921, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was in constant correspondence with Bahá’ís around the world. But during the war, His contacts with those outside the Holy Land were severely restricted.

Still, during this time, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá took on two of His well-known works: Memorials of the Faithful and Tablets of the Divine Plan. The first was the publication of a series of talks He delivered during the war, eulogizing 79 heroic Bahá’ís. The latter was a series of letters, written in 1916 and 1917, that laid the foundation for the global spread of the Bahá’í Faith.

Eventually, during the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá resumed weekly gatherings in His home, warmly greeting visitors and meeting with people from all segments of society, including Ottoman, British, German, and other military and government figures.

“Agony filled His soul at the spectacle of human slaughter precipitated through humanity’s failure to respond to the summons He had issued, or to heed the warnings He had given,” Shoghi Effendi later wrote about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during this time in God Passes By.

Following Haifa’s liberation on 23 September 1918, the city was in a frenzy. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá maintained an atmosphere of calm and dignity as He received a continual flow of visitors including generals, officials, soldiers, and civilians.

News of His safety gave relief to Bahá’ís around the world. With the end of the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would soon meet many more Bahá’ís and other visitors from abroad as the doors to that sacred land were open again.

While Europe was jubilant with the end of the Great War and a world-embracing institution was taking form in the League of Nations, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote in January 1920:

“The ills from which the world now suffers will multiply; the gloom which envelops it will deepen. The Balkans will remain discontented. Its restlessness will increase. The vanquished Powers will continue to agitate. They will resort to every measure that may rekindle the flame of war.”

Conscious of the threat of yet another war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá showed great interest in movements working for peace. In 1919, for example, He corresponded with the Central Organization for a Durable Peace at The Hague, which had written to Him three years earlier. In a message, referred to as the Tablet to The Hague, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, while praising the organization, was also candid in stating that peace would require a profound transformation in human consciousness and a commitment to the spiritual truths enunciated by Bahá’u’lláh.

“At present Universal Peace is a matter of great importance, but unity of conscience is essential, so that the foundation of this matter may become secure, its establishment firm and its edifice strong,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote in that letter. “Today nothing but the power of the Word of God which encompasses the realities of things can bring the thoughts, the minds, the hearts and the spirits under the shade of one Tree.”

In His will, Bahá’u’lláh appointed His oldest son, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, as the authorized interpreter of His teachings and head of the Bahá’í Faith. Upholding unity as the fundamental principle of His teachings, Bahá’u’lláh established a Covenant through which His religion would not split into sects after His passing. Thus, Bahá’u’lláh instructed His followers to turn to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá not only as the authorized interpreter of the Bahá’í writings but also as the perfect exemplar of the Faith’s spirit and teachings.

The sun rises in the Congolese village of Ditalala, and the aroma of freshly brewed coffee fills the air. For generations, the people of this village have been drinking coffee, which they grow themselves, before heading out to work on their farms.

Over the past few years, this morning tradition has come to take on a deeper significance. Many families in the village have been inviting their neighbors to join them for coffee and prayers before starting the day.

“They’ve transformed that simple act of having a cup of coffee in the morning,” says a recent visitor to Ditalala, reflecting on her experience. “It was truly a community-building activity. Friends from the neighboring houses would gather while the coffee was being made, say prayers together, then share the coffee while laughing and discussing the issues of the community. There was a sense of true unity.”

The central African nation of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has experienced, for over a century, a series of violent struggles. The most recent war from 1998–2002 is estimated to have claimed over 5.4 million lives, making it the world’s deadliest crisis since World War II. For the last two years, it has been the country with the highest number of people displaced by conflict—according to the United Nations, approximately 1.7 million Congolese fled their homes due to insecurity in the first six months of 2017 alone.

Yet, there are communities throughout the country that are learning to transcend the traditional barriers that divide people. Inspired by Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, they are striving for progress both material and spiritual in nature. They are concerned with the practical dimensions of life, as well as with the qualities of a flourishing community like justice, connectedness, unity, and access to knowledge.

“What we are learning is that when there are spaces to come together and discuss the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh in relation to the challenges facing their community, people will come and consult about what we can do together to find solutions to our problems,” reflects Izzat Mionda Abumba, who has been working for many years with educational programs for children and youth.

“When everyone is given access to these spaces, there is nothing that separates us—it’s no longer about who are Bahá’ís and who are not Bahá’ís. We are all reading these writings and in discussing them we find the paths to the solutions for whatever we are doing. Inspiration comes from these writings and directives,” he says.

The story of this country is a remarkable one. The process which is unfolding seeks to foster collaboration and build capacity within all people—regardless of religious background, ethnicity, race, gender, or social status—to arise and contribute to the advancement of civilization. Among the confusion, distrust, and obscurity present in the world today, these burgeoning communities in the DRC are hopeful examples of humanity’s capacity to bring about profound social transformation.

A path to collective prosperity

The village of Walungu is in South Kivu, a province on the eastern side of the country, bordering Rwanda and Burundi. In recent years, a spirit of unity and collaboration has become widespread among the people of Walungu. They pray together in different settings, bringing neighbor together with neighbor, irrespective of religious affiliation. This growing devotional character has been complemented by a deep commitment to serving the common good.

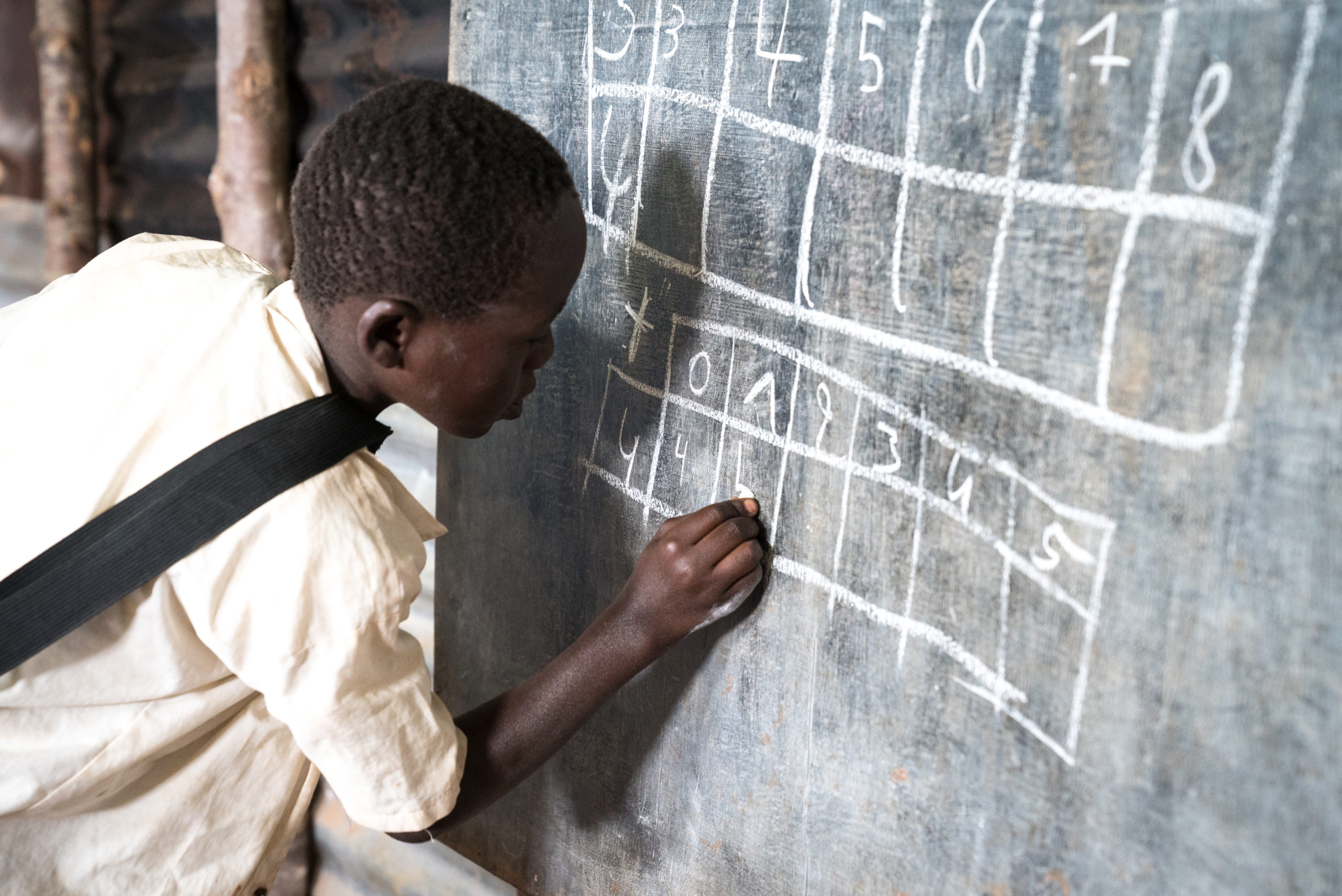

At the heart of Walungu’s transformation has been the dedication of the village to the intellectual and spiritual development of the children.

Walungu is a remote area of the country. Years ago, the community was not satisfied with the state of formal education available for their children. In response, a group of parents and teachers established a school in the village with the assistance of a Bahá’í-inspired organization that provides teacher training and promotes the establishment of community-based schools.

Distinct from traditional educational institutions, community schools, such as the one in Walungu, are initiated, supported, and encouraged by the local community. Parents, extended family, other members of the community, and even the children have a deep sense of ownership and responsibility for the functioning of their school.

When the school opened in 2008, it was comprised of only one grade taught by a single teacher. After a year, the community was able to add another grade and employ a second teacher. Gradually, the school grew, adding more students, grades, and teachers. Today, it is a full primary school with over 100 students.

However, the community faced certain challenges as the school began to grow larger. They did not have the funds to pay the teachers a salary or take care of the school. Realizing that something needed to be done to support the school financially, they called a meeting with all the parents and others involved. At the meeting, the director of the school suggested that he could teach them how to weave baskets, and that if they could sell the baskets in the market they would have some funds that could be used to pay the school fees. Sixty-seven parents signed up, happy at the prospect of learning a new skill and being able to support their children’s education themselves. To this day, all of them are still weaving baskets, which are sold in the markets of the surrounding villages.

Basket-weaving has remained a collective activity—typically, the parents gather to work on them together, sometimes teaching each other new weaving techniques. And these gatherings have become something more. They are a space to talk about spiritual and profound matters as well.

“The women and men are not coming only to weave,” explains Mireille Rehema Lusagila, who is involved in the work of building healthy and vibrant communities. “They begin with a devotional meeting, they read holy writings together. They are improving their literacy, teaching each other how to read and write. The people there have told me that this activity is helping them not only to progress in a material sense but also on a spiritual level.”

Towards unity, youth lead the way

Along the eastern border of the country in the Kivu region, young people are taking ownership of the development of the next generation. In the village of Tuwe Tuwe, there are 15 youth working with some 100 young adolescents and children, helping them to develop a deep appreciation for unity and navigate a crucial stage of their lives.

For several years, youth have been at the vanguard of transformation in this community. In 2013, a group of young Bahá’ís and their friends returned from a youth conference with a great desire to resolve the tension and hostility between their villages.

At the conference, the group studied themes essential to a unified community, such as the importance of having noble goals, the idea of spiritual and material prosperity, the role of youth in serving and improving their localities, and how to support each other in undertaking meaningful action.

In reflecting on the experience, Mr. Abumba, who travels often in the region to support Bahá’í-inspired educational programs, shares a story about how these young people became a force for unity.

“When these youth returned to their respective communities they saw that hostilities were increasing between their two villages because of conflict over their agricultural fields. The youth asked themselves: ‘what can we do to find a solution and help the adults understand that we should live in harmony?’ And they decided to take action together,” says Mr. Abumba.

“The idea they came up with was to organize a football match involving the youth of both villages and to hold it in a field between the villages, in the hopes that the parents would come and watch. For them, it was not about who would win or lose the match. Their goal was to bring a large number of people from both villages together to the same place and to try to give a message about how to live in unity.”

These young people prepared for the match—they bought a football and created the teams of each village with members of different tribes. Finally, the moment came. Quite a big crowd from both villages turned up because it was a Sunday. Those watching were impressed by the way the youth played for the joy of the game.

“Then at the end of the match, the youth spoke to the crowd,” explains Mr. Abumba. “They said ‘You have seen how we played and how there was no conflict between the youth of one village and the youth of the other village. And we believe that our villages are capable of this, of living like the children of one same family.’ Then the chiefs of the villages took the stage and told those gathered that it was time to turn a new page and start to live and work together.

“In these villages, there are different tribes who are often in conflict,” Mr. Abumba concludes. “The people there are drawing on the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh to find ways to address these deep-rooted problems. And the Bahá’í-inspired educational programs are giving youth in particular a voice to be a force for positive change in their communities.”

A village named ‘Peace’

A remote village in the central part of the country, Ditalala is connected to the closest town by a 25 kilometer path, sometimes travelled on foot, sometimes via off-road vehicle.

Susan Sheper, who has lived in the DRC since the 1980s, recalls that on her first visit to Ditalala 31 years ago, some Bahá’ís had come to meet her at the train and walk with her on the five-hour journey by foot to the village. “We got off the train and were just enveloped by this group of singing, happy Bahá’ís, and then they said to us, ‘Can you walk a little bit?’”

And with that Mrs. Sheper was on her way, with an escort of singing Bahá’ís, walking 25 kilometers through the night.

“It was an extraordinary experience,” Mrs. Sheper recalls, “and they never stopped singing, they would just move from one song to the next. You know, they have that experience of having to walk long distances, and it’s the singing that keeps you going because your feet just move to the rhythm.”

Although at that time there was a vibrant Bahá’í community in the village, which used to be called Batwa Ditalala, there were distinct barriers between different groups, including the Bahá’ís.

“So flash forward 31 years, and I went back to Batwa Ditalala,” says Mrs. Sheper. “And one of the things I learned very quickly was that it was no longer called Batwa Ditalala.”

The term Batwa refers to the Batwa people, who are one of the main “Pygmy” groupings in the Democratic Republic of Congo. They have been marginalized and exploited because of discrimination against them based on their hunter-gatherer way of life and their physical appearance. This has created a complex reality of prejudice and conflict wherever they live in close proximity to settled agricultural populations.

“But today, those barriers have been so broken down by Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings of oneness and the elimination of prejudice, they no longer call the village Batwa Ditalala. They just call it Ditalala,” Mrs. Sheper explains.

The word ditalala means peace in the local language—and the village itself has been transformed by a vision of peace.

“The people there told me that there used to be very distinct divisions between them in the village, but that because of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings they don’t see themselves as different tribes anymore, they see themselves as being united,” Mrs. Sheper relates. “They told me that life is much better when there is no prejudice.”

Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings have reached almost everyone in Ditalala and their influence is evident in many dimensions of the lives of the population. Today, over 90 percent of the village participates in Bahá’í community-building activities, ranging from coffee and prayers in the mornings to spiritual and moral education classes for people of all ages.

Ditalala’s chief often supports the activities of the Bahá’í community. He encourages the community to gather for consultation, a central feature of decision-making for Bahá’ís.

The people have also undertaken a number of endeavors to improve their social and material well-being, including agricultural, maternal healthcare, and clean water projects; constructing a road; and establishing a community school.

A luminous community

Throughout the DRC, tens of thousands of people have responded to the message of Bahá’u’lláh. The celebrations of the 200th anniversary of His birth in October were extraordinarily widespread—countless numbers participated in the festivities held across the country. It is estimated that as many as 20 million people saw the television broadcast of the national commemoration, attended by prominent government and civil society leaders.

The country has also been designated by the Universal House of Justice as one of two that will have a national Bahá’í House of Worship in the coming years.

Amidst all of its recent developments, what stands out so vividly about the community is that it is moving forward together.

The podcast associated with this Bahá’í World News Service story, can be found here.

At the heart of human experience lies an essential yearning for self-definition and self-understanding. Developing a conception of who we are, for what purpose we exist, and how we should live our lives is a basic impulse of human consciousness. This project—of defining the self and its place in the social order—expresses both a desire for meaning and an aspiration for belonging. It is a quest informed by ever-evolving and interacting narratives of identity.

Today, as the sheer intensity and velocity of change challenges our assumptions about the nature and structure of social reality, a set of vital questions confront us. These include: What is the source of our identity? Where should our attachments and loyalties lie? And if our identity or identities so impel us, how—and with whom—should we come together? And what is the nature of the bonds that bring us together?

The organization and direction of human affairs are inextricably connected to the future evolution of our identity. For it is from our identity that intention, action, and social development flow. Identity determines how we see ourselves and conceive our position in the world, how others see us or classify us, and how we choose to engage with those around us. “Knowing who we are,” the sociologist Philip Selznick observes, “helps us to appreciate the reach as well as the limits of our attachments.”1Philip Selznick, “Civility and Piety as Foundations of Community,” The Journal of Bahá’í Studies, Vol. 14, number ½, March-June 2004. Also see Philip Selznick, The Moral Commonwealth: Social Theory and the Promise of Community (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), pp. 388—9. Such attachments play a vital role in shaping our “authentic selves” and in determining our attitudes toward those within and outside the circle of our social relationships. Acting on the commitments implied by these attachments serves to amplify the powers of individuals in effecting societal well-being and advancement. Notions of personal and collective identity can thus exert considerable influence over the norms and practices of a rapidly integrating global community.

As we have many associational linkages, identity comes in a variety of forms. At times we identify ourselves by our family, ethnicity, nationality, religion, mother tongue, race, gender, class, culture, or profession. At other times our locale, the enterprises and institutions we work for, our loyalty to sports teams, affinity for certain types of music and cuisine, attachment to particular causes, and educational affiliations provide definitional aspects to who we are. The sources of identification which animate and ground human beings are immensely diverse. In short, there are multiple demands of loyalty placed upon us, and consequently, our identities, as Nobel laureate Amaryta Sen has noted, are “inescapably plural.”2Amartya Sen, Identity and Violence—The Illusion of Destiny (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), p. xiii.

But which identity or identities are most important? Can divergent identities be reconciled? And do these identities enhance or limit our understanding of and engagement with the world? Each of us on a daily basis, both consciously and unconsciously, draws upon, expresses, and mediates between our multiple senses of identity. And as our sphere of social interaction expands, we tend to subsume portions of how we define ourselves and seek to integrate into a wider domain of human experience. This often requires us to scrutinize and even resist particular interpretations of allegiance that may have a claim on us. We therefore tend to prioritize which identities matter most to us. As the theorist Iris Marion Young stresses: “Individuals are agents: we constitute our own identities, and each person’s identity is unique…A person’s identity is not some sum of her gender, racial, class, and national affinities. She is only her identity, which she herself has made by the way that she deals with and acts in relation to others…”3Iris Marion Young, Inclusion and Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 101—2. The matrix of our associations surely influences how we understand and interpret the world, but cannot fully account for how we think, act, or what values we hold. That a particular identity represents a wellspring of meaning to an individual need not diminish the significance of other attachments or eclipse our moral intuition or use of reason. Affirming affinity with a specific group as a component of one’s personal identity should not limit how one views one’s place in society or the possibilities of how one might live.

While it is undoubtedly simplistic to reduce human identity to specific contextual categories such as nationality or culture, such categories do provide a strong narrative contribution to an individual’s sense of being. “Around the world,” the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, “it matters to people that they can tell a story of their lives that meshes with larger narratives. This may involve rites of passage into womanhood and manhood; or a sense of national identity that fits into a larger saga. Such collective identification can also confer significance upon very individual achievements.”4Kwame Anthony Appiah, The Ethics of Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), p. 68. Social, cultural, and other narratives directly impact who we are. They provide context and structure for our lives, allowing us to link what we wish to become to a wider human inheritance, thereby providing a basis for meaningful collective life. Various narratives of identity serve as vehicles of unity, bringing coherence and direction to the disparate experiences of individuals.