The body lies crushed into a well, with rocks over it, somewhere near the center of Ṭihrán. Buildings have gone up around it, and traffic passes along the road near where the garden was. Bushes push donkeys to one side, automobiles from across the world graze the camels’ packs, carriages rock by. Toward sunset men scoop up water from a stream and fling it into the road to lay the dust. And the body is there, crushed into the ground, and men come and go, and think it is hidden and forgotten.

Beauty in women is a relative thing. Take Laylí, for instance, whose lover Majnún had to go away into the desert when she left him, because he could no longer bear the faces of others; whereupon the animals came, and sat around him in a circle, and mourned with him, as any number of poets and painters will tell you—even Laylí was not beautiful. Sa’dí describes how one of the kings of Arabia reasoned with Majnún in vain, and how finally “It came into the king’s heart to look upon the beauty of Laylí, that he might see the face that had wrought such ruin. He bade them seek through the tribes of Arabia and they found her and brought her to stand in the courtyard before him. The king looked at her; he saw a woman dark of skin and slight of body, and he thought little of her, for the meanest servant in his harem was fairer than she. Majnún read the king’s mind, and he said, ‘O king, you must look upon Laylí through the eyes of Majnún, till the inner beauty of her may be manifest.'” Beauty depends on the eyes that see it. At all events we know that Ṭáhirih was beautiful according to the thought of her time.

Perhaps she opened her mirror-case one day—the eight-sided case with a lacquer nightingale singing on it to a lacquer rose—and looked inside, and thought how no record of her features had been made to send into the future. She probably knew that age would never scrawl over the face, to cancel the beauty of it, because she was one of those who die young. But perhaps, kneeling on the floor by the long window, her book laid aside, the mirror before her she thought how her face would vanish, just as Laylí’s had, and Shírín’s, and all the others. So that she slid open her pen-case, and took out the reed pen, and holding the paper in her palm, wrote the brief self-portrait that we have of her: “Small black mole at the edge of the lip—A black lock of hair by either cheek-” she wrote; and the wooden pen creaked as she drove it over the paper.

Ṭáhirih loved pretty clothes, and perfumes, and she loved to eat. She could eat sweets all day long. Once, years after Ṭáhirih had gone, an American woman traveled to ‘Akká and sat at ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s table; the food was good, and she ate plentifully, and then asked the Master’s forgiveness for eating so much. He answered: Virtue and excellence consist in true faith in God, not in having a small or a large appetite for food. … Jinab-i-Ṭáhirih had a good appetite. When asked concerning it, she would answer, “It is recorded in the Holy Traditions that one of the attributes of the people of paradise is ‘partaking of food, continually.’ ”

When she was a child, instead of playing games, she would listen to the theological discussion of her father and uncle, who were great ecclesiastics in Qazvín. Soon she could teach Islam down to the last ḥadíth! Her brother said, “We, all of us, her brothers, her cousins, did not dare to speak in her presence, so much did her knowledge intimidate us.” This from a Persian brother, who comes first in everything, and whose sisters wait upon him. As she grew, she attended the courses given by her father and uncle; she sat in the same hall with two or three hundred men students, but hidden behind a curtain, and more than once refuted what the two old men were expounding. In time some of the haughtiest ‘ulamás consented to certain of her views.

Ṭáhirih married her cousin and gave birth to children. It must have been the usual Persian marriage, where the couple hardly met before the ceremony, and where indeed the suitor was allowed only a brief glimpse of the girl’s face unveiled. Love marriages were thought shameful, and this must have been pre-arranged in the proper way. No, if she ever cared for anyone with a human love, we like to think it was Quddús, whom she was to know in later years; Quddús, who was a descendant of the Imám Ḥasan, grandson of the Prophet Muḥammad. People loved him very easily, they could hardly turn their eyes away from him. He was one of the first to be persecuted for his Master’s Faith on Persian soil—in Shíráz, when they tortured him and led him through the streets by a halter. Later on, it was Quddús who commanded the besieged men at Shaykh Ṭabarsí, and when the Fort had fallen through the enemy’s treachery, and been demolished, he was given over to the mob, in his home city of Bárfurúsh. He was led through the marketplace in chains, while the crowds attacked him. They fouled his clothing and slashed him with knives, and in the end they hacked his body apart and burned what was left. Quddús had never married; for years his mother had lived in the hope of seeing his wedding day; as he walked to his death, he remembered her and cried out, “Would that my mother were with me, and could see with her own eyes the splendor of my nuptials!”

So Ṭáhirih lived in Qazvín, the honey colored city of sunbaked brick, with her slim, tinkling poplars, and the bands of blue water along the yellow dust of the roads. She lived in a honey colored house round a courtyard, cool like the inside of an earthen jar, and there were niches in the whitewashed walls of the rooms, where she set her lamp, and kept her books, wrapped up in hand-blocked cotton cloth. But where other women would have been content with what she had, she could not rest; her mind harried her; and at last she broke away and went over the mountains out of Persia, to the domed city of Karbilá, looking for the Truth.

Then one night she had a dream. She saw a young man standing in the sky; He had a book in His hands and He read verses out of it. Ṭáhirih wakened and wrote down the verses to remember them, and later, when she found the same lines again in a commentary written by the Báb, she believed in Him. At once she spoke out. She broadcast her conversion to the Faith of the Báb, and the result was open scandal. Her husband, her father, her brothers, begged her to give up the madness; in reply she proclaimed her belief. She denounced her generation, the ways of her people, polygamy, the veiling of women, the corruption in high places, the evil of the clergy. She was not one of those who temporize and walk softly. She spoke out; she cried out for a revolution in all men’s ways; when at last she died it was by the words of her own mouth, and she knew it.

Nicolas tells us that she had “an ardent temperament, a just, clear intelligence, remarkable poise, untameable courage.” Gobineau says, “The chief characteristic of her speech was an almost shocking plainness, and yet when she spoke … you were stirred to the bottom of your soul, and filled with admiration, and tears came from your eyes.” Nabíl says that “None could resist her charm; few could escape the contagion of her belief. All testified to the extraordinary traits of her character, marveled at her amazing personality, and were convinced of the sincerity of her conviction.”

Most significant is the memory of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá . When He was a child, Ṭáhirih held Him on her lap while she conversed with the great Siyyid Yaḥyá-i-Dárábí, who sat outside the door. He was a man of immense learning. For example, he knew thirty thousand Islamic traditions by heart; and he knew the depths of the Qur’án, and would quote from the Holy Text to prove the truth of the Báb. Ṭáhirih called out to him, “Oh Siyyid! If you are a man of action, do some great deed!” He listened, and for the first time he understood; he saw that it was not enough to prove the claim of the Báb, but that he must sacrifice himself to spread the Faith. He rose and went out, and traveled and taught, and in the end he laid down his life in the red streets of Nayríz. They cut off his head, and stuffed it with straw, and paraded it from city to city.

Ṭáhirih never saw the Báb. She sent Him a message, telling her love for Him:

The effulgence of Thy face flashed forth and the rays of Thy visage arose on high;

Then speak the word “Am I not your Lord” and “Thou art, Thou art,” we will all reply.

The trumpet-call “Am I not” to greet how loud the drums of affliction beat!

At the gates of my heart there tramp the feet and camp the hosts of calamity…

She set about translating into Persian the Báb’s Commentary on the Súrih of Joseph. And He made her one of the undying company, the Letters of the Living.

We see her there in Karbilá, in the plains where more than a thousand years before, Imám Ḥusayn, grandson of the Prophet, had fallen of thirst and wounds. We see her on the anniversary of his death, when all the town was wailing for him and all had put on black in his memory, decked out in holiday clothing to celebrate the birthday of the Báb. This was a new day, she told them; the old agonies were spent. Then she traveled in her howdah, a sort of curtained cage balanced on a horse, to Baghdád and continued her teaching. Here the leaders of the Shí’ih and Sunní, the Christian and Jewish communities sought her out to convince her of her folly; but she astounded them and routed them and in the end she was ordered out of Turkish territory, and she traveled toward Persia, gathering disciples for the Báb. Everywhere princes, ‘ulamás, government officials crowded to see her; she was praised from a number of pulpits; one said, “Our highest attainments are but a drop compared to the immensity of her knowledge.” This of a woman, in a country of silent, shadow-women, who lived their quiet cycle behind the veil: marriage and sickness and childbirth, stirring the rice and baking the flaps of bread, embroidering a leaf on a strip of velvet, dying without a name.

Karbilá, Baghdád, Kirmánsháh, Hamadán. Then her father summoned her home to Qazvín, and once she was back in his house, her husband, the mujtahid, sent for her to return and live with him. This was her answer: “Say to my presumptuous and arrogant kinsman … ‘If your desire had really been to be a faithful mate and companion to me, you would have hastened to meet me in Karbilá and would on foot have guided my howdah all the way to Qazvín. I would … have aroused you from your sleep of heedlessness and would have shown you the way of truth. But this was not to be. … Neither in this world nor in the next can I ever be associated with you. I have cast you out of my life forever.’ ” Then her uncle and her husband pronounced her a heretic, and set about working against her night and day.

One day a mullá was walking through Qazvín, when he saw a gang of ruffians dragging a man along the street; they had tied the man’s turban around his neck for a halter, and were torturing him. The bystanders said that this man had spoken in praise of two beings, heralds of the Báb; and for that, Ṭáhirih’s uncle was banishing him. The mullá was troubled in his mind. He was not a Bábí, but he loved the two heralds of the Báb. He went to the bazar of the swordmakers, and bought a dagger and a spearhead of the finest steel, and bided his time. One dawn in the mosque, an old woman hobbled in and spread down a rug. Then Ṭáhirih’s uncle entered alone, to pray on it. He was prostrating himself when the mullá ran up and plunged the spearhead into his neck; he cried out, the mullá flung him on his back, drove the dagger deep into his mouth and left him bleeding on the mosque floor.

Qazvín went wild over the murder. Although the mullá confessed, and was identified by his dying victim, many innocent people were accused and made prisoner. In Ṭihrán, Bahá’u’lláh suffered His first affliction—some days’ imprisonment—because He sent them food and money and interceded for them. The heirs now put to death an innocent man, Shaykh Ṣáliḥ, an Arab from Karbílá. This admirer of Ṭáhirih was the first to die on Persian soil for the Cause of God; they killed him in Ṭihrán; he greeted his executioner like a well-loved friend, and his last words were, “I discarded . … the hopes and beliefs of men from the moment I recognized Thee, Thou Who art my hope and my belief!”

The remaining prisoners were later massacred, and it is said that no fragments were left of their bodies to bury.

But still the heirs were not content. They accused Ṭáhirih. They had her shut up in her father’s house and made ready to take her life; however, her hour was not yet come. It was then that a beggar-woman stood at the door and whined for bread; but she was no beggar-woman—she brought word that one sent by Bahá’u’lláh, was waiting with three horses near the Qazvín gate. Ṭáhirih went away with the woman, and by daybreak she had ridden to Ṭihrán, to the house of Bahá’u’lláh. All night long, they searched Qazvín for her, but she had vanished.

The scene shifts to the gardens of Badasht. Mud walls enclosing the jade orchards, a stream spread over the desert, and beyond, the sharp mountains cutting into the sky. The Báb was in His prison at Chihríq — “The Grievous Mountain.” He had two short years to live.

And now Bahá’u’lláh came to Badasht, with eighty-one leading Babís as His companions. His destiny was still unguessed. He, the Promised One of the Báb—of Muḥammad, of Christ, of Zoroaster, and beyond Them of prophet after prophet down into the centuries—was still unknown. How could they tell, at Badasht, that His name would soon be loved around the world? How could they hear it called upon, in cities across the earth; strange, unheard of places: San Francisco, Buenos Aires, Adelaide? How could they see the unguessed men and women that would arise to serve that name? But Ṭáhirih saw. “Behold,” she wrote, “the souls of His lovers dancing like motes in the light that has flashed from His face!”

It was in this village of Badasht that the old laws were broken. Up to these days, the Babís had thought that their Master was come to enforce Islám; but here one by one they saw the old laws go. And their confusion mounted, and their trouble, and some held to the old ways and could not go forward into the new.

Then one day, as they sat with Bahá’u’lláh in the garden, an unbearable thing came to pass. Ṭáhirih suddenly appeared before them, and she stood in their presence with her face unveiled. Ṭáhirih so holy; Ṭáhirih, whose very shadow a man would turn his eyes from; Ṭáhirih, the most venerated woman of her time, had stripped the veil from her face, and stood before them like a dancing girl ready for their pleasure. They saw her flashing skin, and the eyebrows joined together, like two swords, over the blazing eyes. And they could not look. Some hid their faces in their hands, some threw their garments over their heads. One cut his throat and fled shrieking and covered with blood.

Then she spoke out in a loud voice to those who were left, and they say her speech came like the words of the Qur’án. “This day,” she said, “this day is the day on which the fetters of the past are burst asunder—I am the Word which the Qá’im is to utter, the Word which shall put to flight the chiefs and nobles of the earth!” And she told them of the old order, yielding to the new, and ended with a prophetic verse from the Holy Book: “Verily, amid gardens and rivers shall the pious dwell in the seat of truth, in the presence of the potent King.”

Ṭáhirih was born in the same year as Bahá’u’lláh, and she was thirty-six when they took her life. European scholars have known her for a long time, under one of her names, Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, which means “Solace of the Eyes.” The Persians sing her poems, which are still waiting for a translator. Women in many countries are hearing of her, getting courage from her. Many have paid tribute to her. Gobineau says, after dwelling on her beauty, “(but) the mind and the character of this young woman were much more remarkable.” And Sir Francis Younghusband: ” … she gave up wealth, child, name and position for her Master’s service. … And her verses were among the most stirring in the Persian language.” And T. K. Cheyne, ” … one is chiefly struck by her fiery enthusiasm and by her absolute unworldliness. This world was, in fact, to her, as it was … to Quddús, a mere handful of dust.”

We see her now at a wedding in the Mayor’s house in Ṭihrán. Her curls are short around her forehead, and she wears a flowered kerchief reaching cape-wise to her shoulders and pinned under her chin. The tight-waisted dress flows to the ground; it is handwoven, trimmed with brocade and figured with the tree-of-life design. Her little slippers curl up at the toes. A soft, perfumed crowd of women pushes and rustles around her. They have left their tables, with the pyramids of sweets in silver dishes. They have forgotten the dancers, hired to stamp and jerk and snap their fingers for the wedding feast. The guests are listening to Ṭáhirih, she who is a prisoner here in the Mayor’s house. She is telling them of the new Faith, of the new way of living it will bring, and they forget the dancers and the sweets.

This Mayor, Maḥmúd Khán, whose house was Ṭáhirih’s prison, came to a strange end. Gobineau tells us that he was kind to Ṭáhirih and tried to give her hope, during those days when she waited in his house for the sentence of death. He adds that she did not need hope. That whenever Maḥmúd Khán would speak of her imprisonment, she would interrupt, and tell him of her Faith; of the true and the false; of what was real, and what was illusion. Then one morning, Maḥmúd Khán brought her good news; a message from the Prime Minister; she had only to deny the Báb, and although they would not believe her, they would let her go.

“Do not hope,” she answered, “that I would deny my Faith … for so feeble a reason as to keep this inconstant, worthless form a few days longer. … You, Maḥmúd Khán, listen now to what I am saying. … The master you serve will not repay your zeal; on the contrary, you shall perish, cruelly, at his command. Try, before your death, to raise your soul up to knowledge of the Truth.”1Gobineau, Comte de, Les Religions et les Philosophies dans l’Asie Centrale, p. 242. He went from the room, not believing. But her words were fulfilled in 1861, during the famine, when the people of Ṭihrán rioted for bread.

Here is an eye-witness’ account of the bread riots of those days; and of death of Maḥmúd Khán: “The distress in Ṭihrán was now culminating, and, the roads being almost impassable, supplies of corn could not reach the city. … As soon as a European showed himself in the streets he was surrounded by famishing women, supplicating assistance … on the 1st of March … the chief Persian secretary came in, pale and trembling, and said there was an émeute, and that the Kalántar, or mayor of the city, had just been put to death, and that they were dragging his body stark naked through the bazars. Presently we heard a great tumult, and on going to the windows saw the streets filled with thousands of people, in a very excited state, surrounding the corpse, which was being dragged to the place of execution, where it was hung up by the heels, naked, for three days.

“On inquiry we learned that on the 28th of February, the Sháh, on coming in from hunting, was surrounded by a mob of several thousand women, yelling for bread, who gutted the bakers’ shops of their contents, under the very eyes of the king. … Next day, the 1st of March … the Shah had ascended the tower, from which Hajji Baba’s Zainab was thrown, and was watching the riots with a telescope. The Kalántar … splendidly dressed, with a long retinue of servants, went up to the tower and stood by the Sháh who reproached him for suffering such a tumult to have arisen. On this the Kalántar declared he would soon put down the riot, and going amongst the women with his servants, he himself struck several of them furiously with a large stick. … On the women vociferously calling for justice, and showing their wounds, the Shah summoned the Kalántar and said, ‘If thou art thus cruel to my subjects before my eyes, what must be thy secret misdeeds!’ Then turning to his attendants, the king said, — ‘Bastinado him, and cut off his beard.’ And again, while this sentence was being executed, the Shah uttered that terrible word, Tanáb! ‘Rope! Strangle him!’”

One night Ṭáhirih called the Kalántar’s wife into her room. She was wearing a dress of shining white silk; her hair gleamed, her cheeks were delicately whitened. She had put on perfume and the room was fragrant with it.

“I am preparing to meet my Beloved,” she said. “… the hour when I shall be arrested and condemned to suffer martyrdom is fast approaching.”

After that, she paced in her locked room, and chanted prayers. The Kalántar’s wife stood at the door, and listened to the voice rising and falling, and wept. “Lord, Lord,” she cried, “turn from her … the cup which her lips desire to drink.” We cannot force the locked door and enter. We can only guess what those last hours were. Not a time of distributing property, of saying good-bye to friends, but rather of communion with the Lord of all peoples, the One alone Beloved of all men. And His chosen ones, His saints and His Messengers, They all were there; They are present at such hours; she was already with Them, beyond the flesh.

She was waiting, veiled and ready, when they came to take her. “Remember me,” she said as she went, “and rejoice in my gladness.” She mounted a horse they had brought and rode away through the Persian night. The starlight was heavy on the trees, and nightingales rustled. Camel-bells tinkled from somewhere. The horses’ hooves thudded in the dust of the road.

And then bursts of laughter from the drunken officers in the garden. Candles shone on their heavy faces, on the disordered banquet-cloth, the wine spilling over. When Ṭáhirih stood near them, their chief hardly raised his head. “Leave us!” he shouted. “Strangle her!” And he went back to his wine.

She had brought a silk handkerchief with her; she had saved it for this from long ago. Now she gave it to them. They twisted it round her throat, and wrenched it till the blood spurted. They waited till her body was quiet, then they took it up and laid it in an unfinished well in the garden. They covered it over and went away, their eyes on the earth, afraid to look at each other.

Many seasons have passed over Ṭihrán since that hour. In winter the mountains to the north have blazed with their snows, shaken like a million mirrors in the sun. And springs came on, with pear blossoms crowding the gardens, and blue swallows flashing. Summertimes, the city lay under a dust-cloud, and people went up to the moist rocks, the green clefts in the hills. And autumns, when the boughs were stripped, the dizzy space of plains and sky circled the town again. Much time has passed, almost a hundred years since that night.

But today there are a thousand voices where there was one voice then. Words in many tongues, books in many scripts, and temples rising. The love she died for caught and spread, till there are a thousand hearts offered now, for one heart then. She is not silent, there in the earth. Her lips are dust, but they speak.

I am happy to speak to you this evening about one of the greatest young women in the world, one of the most spiritual, one of the greatest poets of Írán, and the first woman of her time in Central Asia to lay aside the veil and work for the equal education of the girl and the boy. She was the first suffrage martyr in Central Asia. The woman suffrage movement did not begin with Mrs. Pankhurst in the West, but with Ṭáhirih, also often called Qurratu’l-‘Ayn of Írán. She was born in Qazvín, Persia, in 1817.

Picture to your mind one of the most beautiful young women of Írán, a genius, a poet, the most learned scholar of the Qur’an and the traditions, for she was born in a Muhammadan country; think of her as the daughter of a jurist family of letters, daughter of the greatest high priest of her province and very rich, enjoying high rank, living in an artistic palace, and distinguished among her young friends for her boundless, immeasurable courage. Picture what it must mean for a young woman like this, still in her twenties, to arise for the equality of men and women, in a country where, at that time, the girl was not allowed to learn to read and write!

The Journal Asiatic of 1866 presents a most graphic view of Ṭáhirih, the English translation of which is this: “How a woman, a creature so weak in Írán, and above all in a city like Qazvín where the clergy possess such a powerful influence, where the ‘Ulamás, the priests, because of their number and importance and power hold the attention of the government officials and of the people, how can it be that in such a country and district and under such unfavourable conditions a woman could have organized such a powerful party of heretics? It is unparalleled in past history.”

As I said, in her day girls were not permitted to learn to read and write, but Ṭáhirih had such a brilliant mind, and as a child was so eager for knowledge that her father, one of the most learned mullás of Írán, taught her himself and later had a teacher for her. This was most unusual, for in her day girls had no educational opportunities. She outdistanced her brothers in her progress and passed high in all examinations. Because she was a woman they would not give her a degree. Her father often said what a pity she had not been born a son, for then she could have followed in his career as a great mullá of the Empire.

Ṭáhirih was married when she was thirteen years old to her cousin, the son of the Imám-Juma, a great mullá who leads the prayers at the mosque on Fridays. She had three children, two sons and one daughter. She became a very great poet and was deeply spiritual, she was always studying religion, always seeking for truth. She became profoundly interested in the teachings of Shaykh Aḥsá’í and Siyyid Káẓím Rashti, who were liberalists and said great spiritual reforms would come. Her father was very angry with her because she read their books and her father-in-law was too. But she continued to study their books and she heard about the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh, and their teachings for universal peace and the equal education of the girl and the boy. She believed in these principles whole-heartedly and declared herself a believer.

This great young woman of Qazvín laid aside the veil which Muhammadan women wear; she didn’t put it aside altogether, but she many times let it slip from her face when she lectured. But she declared that women should not wear the veil, should not be isolated, but should have equal rights and opportunities. She quoted her great teacher, Bahá’u’lláh, that man and woman are as the two wings of the bird of humanity, and this bird of humanity cannot attain its highest, most perfect flight until the two wings are equally poised, equally balanced. She was too far ahead of her time, and like other pioneers of great progressive movements, she was imprisoned. Instead of putting her into jail, they made her a prisoner in the home of the Kalantar, that means the Mayor of Ṭihrán. Here several poets and some of the greatest women of the capital came to call, and every one was charmed by her presence. The Sháh-in-Sháh of Persia sent for her to be brought to his palace, and when he saw her he said: “I like her looks, leave her and let her be.”

Náṣiri’d-Dín-Sháh, the ruler, sent her a letter asking her to give up her very advanced ideas and telling her if she did, he would make her his bride, the greatest lady in the land. On the back of his letter she wrote her reply in verse declining his magnificently royal offer. Her words were:

“Kingdom, wealth and ruling be for thee,

Wandering, becoming a poor dervish and calamity be for me.

If that station is good, let it be for thee.

And if this station is bad, I long for it, let it be for me!”

She was a prisoner in the Mayor’s home for more than three years and during all this time the women of Írán came to love her more and more, and all people were enchanted with her poetry, and many came to believe as she did, that this is the dawn of a great new universal epoch when we must work for the oneness of mankind, for the independent investigation of truth, for the unity of religions and for the education of the girl equally with that of the boy. The orthodox clergy were afraid of these new progressive ideals and as they were the power behind the government, it was decided to put Ṭáhirih to death. They had to do it secretly because they knew how many hundreds of the most important people in Ṭihrán loved her.

They decided upon September 15, 1852, for her death. With her prophetic soul she must have divined it for she wrote in one of her poems: “At the gates of my heart I behold the feet and the tents of hosts of calamity.” That morning she took an elaborate bath, used rosewater, dressed herself in her best white dress. She said good-bye to everyone in the house, telling them that in the evening she was leaving to go on a long journey. After that she said she would like to be alone, and she spent the day, as they said, talking softly to herself, but we know she was praying. They came for her at night and she said to them, “I am ready!” The Mayor had them throw his own cloak about her so that no one would recognize her, and they put her upon his own horse. In a roundabout way through smaller streets they took her to a garden and had her wait in a servant’s room on the ground floor. The official called a servant and ordered him to go and kill the woman downstairs. He went but when Ṭáhirih spoke to him he was so touched by her sweetness and holiness, that he refused to strangle her, and carried the handkerchief again upstairs. The official dismissed him, called a very evil servant, gave him liquor to drink, then handed him a bag of gold as a present, put the handkerchief into his hands and said, “Go down and kill that woman below and do not let her speak to you.” The servant rushed in, brutally strangled her with the handkerchief, kicked her and while she was still living threw her into a dry well and filled it up with stones.

But they could not bury her there! Her influence had gone around the whole world. Ṭáhirih, Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, has become immortal in the minds of millions of men and women, and her spirit of love and heroism will be transmitted to millions yet unborn.

I should like to explain to you what her names mean. One of her teachers, Káẓím Rashti gave her the name of Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, which means “Consolation of the Eyes,” because she was so young, so beautiful, so spiritual. Bahá’u’lláh gave her the name Ṭáhirih, which means “The Pure One.” While still in the twenties she began to preach the equal rights of men and women, she was martyred at the age of thirty-six years, and yet today, eighty-seven years after her cruel martyrdom, the women of Írán and of many other countries of the Islámic world no longer are allowed to wear the veil, and girls are receiving education. She did not die in vain. Ṭáhirih’s courageous deathless personality forever will stand out against the background of eternity, for she gave her life for her sister women. The sweet perfume of her heroic selflessness is diffused in the whole five continents. People of all religions and of none, all races, all classes, all humanity, cherish the memory of Ṭáhirih and weep tears of love and longing when her great poems are chanted.

When I was in Vienna, Austria, a few years ago, I had an interview with the mother of the President of Austria, Mrs. Marinna Hainisch, the woman who has done most for woman’s education in Austria, that nation of great culture. Mrs. Hainisch established the first high schools for girls in her land. She told me that the inspiration of all her lifework had been Ṭáhirih of Írán. Mrs. Hainisch said: “I was a young girl, only seventeen years old when I heard of the martyrdom of Ṭáhirih, and I said, ‘I shall try to do for the girls of Austria what Ṭáhirih tried to do and gave her life to do, for the girls of Írán.’” She told me: “I was married, and my husband too, was only seventeen; everybody was against education for girls, but my young husband said: ‘If you wish to work for the education of girls, you can.’” I mentioned this interview over in Aligrah, India, a short time ago when I spoke to the university students at the home of Professor Ḥabíb, and at the close of my talk another guest of honor arose, a woman professor of Calcutta University, and asked if she could speak a few words. She said, “I am Viennese, I was born in Vienna and I wish to say that Mrs. Marinna Hainisch established the first college for the higher education of girls in Austria and I was graduated from the college.” This is a proof of the influence of Ṭáhirih. Mrs. Hainisch had said to me, “It is so easy for you, Miss Root, to go all around the world and be given the opportunity to speak on the equal education of the girl and the boy. It was so hard for me to interest people in this new idea in my day, but I remembered Ṭáhirih and I tried. Poor Ṭáhirih had to die for these very ideals which today the world accepts!”

When I was in Cawnpore, India, and spoke in a girls’ college on Ṭáhirih’s life the founder and the donor of that great college arose and said: “It is my hope that every girl in this school will become a Ṭáhirih of India.”

Sir Rai Bahadur Sapru of Allahabad, one of India’s greatest lawyers, said to me: “I love Ṭáhirih’s poems so much that I have named my favorite little granddaughter Ṭáhirih. I have tried for years to get her poems, and now today you give them to me.” When I was in the Pemberton Club in London one evening, a well known publisher said to me: “I shall get Ṭáhirih’s poems collected and publish them at a great price.” But he could never get them. I should like to tell you, dear listeners on the air, that the day after the martyrdom of Ṭáhirih, the authorities burned her clothing, her books, her poems, her birth certificate; they tried to wipe out every trace of her life; but other people had some of her poems, and a friend of mine worked for years to gather them together, copied them in longhand and gave them to me as a present when I was in Írán in 1930. Another friend in India, Mr. Isfandiar K. B. Bakhtiari of Karachi, has twice published one thousand copies of these poems for people in India. In my book Ṭáhirih the Pure, Írán’s Greatest Woman, published July, 1938, I included her poems and published three thousand copies. Two of these poems are translated into English, but the original poems are all in the Persian language. They would be very beautiful sung in the Persian language over your radio.

Professor Edward G. Browne of Cambridge University, in his book A Traveller’s Narrative, wrote: “The appearance of such a woman as Ṭáhirih, Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, is in any country and in any age a rare phenomenon, but in such a country as Persia it is a prodigy, nay, almost a miracle. Alike in virtue of her marvelous beauty, her rare intellectual gifts, her fervid eloquence, her fearless devotion and her glorious martyrdom, she stands forth incomparable amidst her countrywomen. Had the Bábí religion no other claim to greatness, this were sufficient, that it produced a heroine like Qurratu’l-‘Ayn.”

And now dear listeners, that we have heard of Ṭáhirih, Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, this first woman suffrage martyr, this first woman in Central Asia to work for the education of girls, what will our own endeavors show forth in this twentieth century?

Today you have equal education for girls and boys in Australia, and you have suffrage for women; but you in Australia and we in the United States and in all other parts of the globe are born into this world to work for universal peace, disarmament, a world court and a strong international police force to ensure arbitration. We are born into this world to work for universal education, a universal auxiliary language, for unity in religion and for the oneness of mankind. Our lives, our world, need strong spiritual foundations, and one of the finest traits of Ṭáhirih, and one that helped the world most, was her fidelity in searching for truth! She began as a little girl and continued until the very day of her passing from this world.

O Ṭáhirih, you have not passed out, you have only passed on! Your spiritual, courageous life will forever inspire, ennoble and refine humanity; your songs of the spirit will be treasured in innumerable hearts. You are to this day our living, thrilling teacher!

1.

Religious bigotry and prejudice are chiefly due to religions being viewed as historical rather than as functional events. The followers of every great world religion tend to look upon their own revelation and the institutions built around it as unique in the history of the planet and consequently to deny the authenticity of other world religions. Hence a bitter rivalry has arisen between religions making such monopolistic claims.

When, however, we take a scientific view of a religion as functional in the development of humanity we are able to look not only with tolerance but with sympathy at other religions than our own. Wherever a sincere spiritual force is effective in the lives of a people, there we see a religion which we may respect. When, however religious expression degenerates into institutionalism either at home or abroad, we may know that religion is no longer performing its normal function.

The function of religion is: first, to make humanity God-conscious; second, to make humanity obedient to the Divine Will (this implies today the unifying of humanity); and third, to bring to each human being the understanding of how to make use of prayer and guidance and thus take advantage of the inestimable privileges offered man by the Divine Power in the way of communion and help.

2.

Religions do not come into being by accident. No great historic epoch and no section of the world has been deprived by Destiny of the opportunity to acquire the priceless treasures of true religion. The spiritual evolution of the human race is as much a part of the majestic plan of the Creator as is the evolution of solar systems. Were it not for the instructive, stimulative and inspirational power of religion upon the heart and conscience of humanity, men would remain morally on a level with animals. In other words they would be unmoral, without the refined conscience which spiritual man possesses. They would be creatures of impulse and of instinct, following the law of the herd but not recognizing that as the only law outside themselves to be obeyed.

Religion brings to man a new conscience, instructing him in the higher laws of living which make for harmony, happiness and prosperity both in an individual and a collective sense. Through religion man is enabled to transcend to himself to become nobler than his biologically inherent animal qualities would permit. Through religion he is trained to sublimate all of these animal qualities – qualities perfectly legitimate in their own field but obstructive to the development of a catholic and harmonious human society.

Through religion man is made aware of his spiritual potentiality. He learns that his soul can aspire in the realm of spirit and need not be dragged and weighted down by all the heavy burdens of carnality. Like a young child learning to walk, he begins to realize powers which he can put into practice. In the use of faith, prayer and spiritual guidance he becomes more and more proficient, growing daily nearer to the full stature of spiritual manhood for which he is destined.

Can any one deny that these are the purposes and these the effects of religion? Any unbiased scientific study of the history of religion as a moral, social and spiritual force in the life of humanity will substantiate the foregoing statements.

3.

But whence does religion spring? Here we come to a much mooted question. We are told by the Founders of the world’s great religions that the truth which they teach is revealed to them from the Divine Source itself; that they are but channels for the Divine instruction and power to flow through; and that their word is, indeed, the Word of God.

Such is the claim of all the great Revelators. But the attitude of science during the last century has been to disparage such super-human claims. From the scientific point of view there seems little chance of objectively proving the claims of revelation. The scientific mind can investigate everything in the phenomenal universe, but it cannot investigate the Mind and Ways of God. Here is a field distinctly barred to the scientific approach. There is only one standpoint from which the claims of revelation might be investigated, appraised and corroborated. This standpoint is the field of actual religious achievement.

When we study the force which inheres in every great world religion – a force definite and unique, a force which, while its sources may be beyond our investigation, as regards its workings and effects lies clearly within the field of scientific investigation – what do we see? History shows that every great religion in the days of its purity – before institutionalism and human dogma begin their taints – exerts a terrific force upon human conduct and human character, a force unparalleled in the history of human morals as regards its contagiousness, its miraculous power to change character, and its quality of sustained application to the art of living on the part of the individual adherent. This force of religion is indeed mysterious – as mysterious as is the force of electricity.

Can we reasonably conceive that such a force can emanate from a source no higher than human mentality? Are these Founders of religion simply spiritual geniuses who are but a few degrees loftier in moral and spiritual insight than their fellows? If so, how could they produce these magical effects upon human nature, both individually and collectively? Effects which last not for a day, but for milleniums. Effects which no founders of schools of philosophies, not even the greatest, have ever been able even in the slightest degree to approximate. Secondly, we should have to assume that in their claims of revelation the Founders of the great world religions were either using deliberate falsehood or suffering under hallucinations. Both of these points of view have been taken. Previous to the religious tolerance of the twentieth century it had been the custom for earnest adherents of Christianity to accuse the founders of other world religions as being hypocrites, falsifiers or emissaries of evil. The theological doctrine of the uniqueness of Christianity induced this attitude. But as scientific liberalism made inroads into Christian theology and the history of religion came to be studied without prejudice of sectarianism, it became apparent to scientific historical observation that such characters as Confucius, Buddha, Zoroaster and Muhammad were not uttering deliberate falsehoods when they claimed to be channels of Divine communication to humanity. They were at least sincere, there could be no question about that. Ergo – assuming the impossibility of substantiating this claim of divine revelation – certain materialistically inclined scholars of comparative religion, abnormal psychologists, and other secularists were led to the conclusion that these claimants to divine revelation were suffering from hallucinations.

Has not science, in its materialistic scepticism, brought itself here into a ridiculous dilemma? Those beings so pure and sinless in character, so noble in their self-sacrificing lives that no other humans can even be put in the same category; those beings who have expressed lofty truths which humanity has intuitively accepted as a perfect pattern for human behavior; those beings the power of whose exemplary lives and exalted teachings has influenced humanity more than any other force, – can it be that these great souls were merely insane? That their conception of the nature of their mission and the source of their wisdom was not only fallacious but the expression of psychologically diseased natures? Marching these Revealers of noble faith and living against opinions of modernistic secularists, I cannot see how the verdict of thoughtful people can be cast in favor of the materialistic psychologist.

4.

Is the idea of revelation, then, so impossible from the scientific point of view? The painter, the poet, the composer feel that their inspirations come from some source greater than themselves. Plato, the greatest creative thinker and literary artist the world has ever produced, had a definite theory as to where his inspirations came from. The artist, he states, is but a channel for images and truths which come to him from the World of the Ideal. The soul of the great artist is able to contact this higher archetypal world where perfection already exists, and thus bring to earth artistic revelations, creative ideas, and discoveries in the realm of truth. Since Plato was himself such a colossally creative thinker, we must acknowledge at least some importance to this theory of his regarding the nature of inspiration and creation.

Many a great artist, thinker, and inventor since the day of Plato has felt this same way about the nature of inspiration. Their greatest works have seemed to them not so much the manufacture of their own limited mentality as a projection, through the sensitivity of their being, of truth or beauty from some world outside themselves.

In fact, so disparate from their creator are the greatest achievements of the creative soul that he must look with a feeling of awe upon these creations emanating through him and enjoy them in a purely impersonal relation, receiving from them an inspiration as from a force totally and miraculously outside of his own personality.

Now if it is a possibility for any creative person to receive all inspiration from some mysterious source outside himself, it is certainly possible for the prophetic soul of a great world Saviour to become a channel for those Divine Forces which seek to guide and stimulate this planet into higher spiritual evolution.

Not only do these Teachers of religion proclaim a truth greater than they themselves could originate, but they are born into the world already destined for such a mission. Their station is above that of ordinary mortals, as the station of the ambassador of a great emperor is peerless in whatever country he may officially abide. “They are the Treasuries of divine knowledge, and the Repositories of celestial wisdom. Through them is transmitted a grace that is infinite, and by them is revealed the light that can never fade.”1Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-i-Íqán. Available at www.bahai.org/r/077907308

5.

These great messengers of God are an essential part of the Divine plan for the evolution of humanity. Biological evolution has gone as far as it is able to go when it has produced “homo sapiens” – man with the power of thought. The further evolution of man in the way of development of his creative intelligence and his spiritual progress depend upon forces from a higher plane. Religion is this force absolutely essential to man’s spiritual evolution, to the awakening and training of potential qualities which elsewise would never come into active expression.

Evolution now ceases to be a something which operates on man apart from his own conscious effort. Progress beyond primitive man he can make only by voluntary conscious effort. It is to awaken and aid this effort toward higher spiritual self-development of humanity that these great Teachers come to earth. Without the inspiration of their teachings and the dynamic stimulus to spiritual progress which they give to man by means of a tremendous outpouring of that cosmic, spiritual, creative force which has been called the Holy Spirit, man would remain on the moral and mental level of the animal.

“Further evolution, if it takes place,” says P. D. Ouspensky in his “Tertium Organum,” “cannot be an elemental and unconscious affair, but will result solely from conscious efforts toward growth. Man, not striving toward evolution, not conscious of its possibility, not helping it, will not evolve. And the individual who is not evolving does not remain in a static condition, but goes down, degenerates. This is the general law.”

6.

An important point to consider here is that the revelations of religion do not come by chance. They are part of a continuous plan for the spiritual evolution of humanity. They are a special communication and dispensation of that great creative and guiding Force of the universe which we call God, and they are revealed through spiritualized beings who are special channels for the flow of this creative force.

Humanity, like a battery which has to be recharged, is under the necessity of fresh spiritual impulse at stated intervals. Fortunately for the spiritual evolution of humanity, at every epoch when one religion has been outgrown a new religion has magically arisen – a religion full of vital hope and promise and charged with the power to remold and to remake the lives of its communicants.

“In their essence all these religions are one. Spiritual Truth cannot, indeed, be different and conflicting. The aims of all the great prophets were one: to bring human beings into the Divine Consciousness, to advance their spiritual development, and to effect better conditions of organized living.

“Nor can the great Founders of religions be supposed to exist in any sort of rivalry one to the other. Their purpose is one. Their devotion to Divinity is one. Their devotion to humanity is one. There can be no possibility of rivalry between these great Souls whose first requisite is abnegation of self, whose words and deeds are guided by divine inspiration, and whose lives serve no other purpose than to mirror Divinity to man.”2Cobb, Security for a Failing World.

From this point of view it will be seen that no religion is final. As humanity develops, it acquires capacity for new and higher revelations. At the same time that its capacity to comprehend is constantly increased, its ability to lead a spiritual life periodically diminishes (as has already been shown), thus necessitating a regular and definite reoccurrence of spiritual revelation.

Each Founder of a great religion gives warning of this to His followers. He speaks of a Return, and warns them to be open and receptive to Truth when it returns again, as return it must when the gradual crystallization and degeneration of established religion takes place through institutionalism and the natural carnal proclivities of man.

7.

Today it is apparent that all over the world religion is in great need of renewal. The spiritual consciousness of humanity is suffering eclipse. This is true not only of Christianity but also of every other great world religion – Confucianism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and Muhammadanism. With the normal restraints of religion removed, with man’s spiritual conscience obscured as his scientific intelligence is accentuated, we see taking place a rapidly growing chaos and a threatened disintegration of world civilization.

Clearly the time is ripe for a renewal of man’s spiritual consciousness, and that renewal is already offered the world in the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh. Here we find not only a renewal of all the spiritual beauty and dynamic force of previous revelations, but also pronouncements especially adapted to the advanced needs of this day. We have not only general moral laws, but their definite application to individual and collective living. We have a comprehensive set of principles upon which the establishment of a great world order is predicated, and a great world civilization of a perfection such as the past has hardly ventured to dream of.

8.

Of all the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh, perhaps none is so needed as the clear enunciation which He gives regarding the continuity of religion. As we have pointed out at the beginning of this article, the lack of such realization has been the cause of the crystallization of religious thought and expression and its disintegration into religious rivalries and hostilities never intended by the Divine Power from whose great Purpose for humanity all religions emanate.

Bahá’u’lláh makes clear not only that His Revelation is a renewal of spiritual truth and potency necessitated by the decline of spiritual consciousness throughout the world; but also that, just as other religions have faded and declined, so the religious expression built around His message is also destined to decadence, in the course of time. Thus He definitely prepares His followers and safeguards them against the dangers of bigotry, of religious smugness, and of blindness to the just and verifiable claims of a new Revelator when His day arrives.

How refreshing is this view of religion, which is now seen as a part of the normal functioning of our planetary life, as necessarily recurrent as are the seasons. Indeed each religion passes through its phases of growth comparable to the seasons – its springtime of blossoming and rejuvanescence, its summer of growth, its autumn of rich fruitage, and its winter of crystallization and decline.

And now again a spiritual springtime has appeared, and the Holy Spirit is pouring down Its rays upon this planet with a potency that is stirring everything to rapid motion and renewed growth. And as in the springtime old forms of vegetation, which in their sear and withered stiffness have lingered through the winter, become broken up by the actinic force of the sun and give way to marvelous new growths whose nourishment they help to furnish by their own decay, so today ancient institutions are falling and every old form is yielding ground to a marvelous newness, which, however disconcerting it may be to unprepared minds, is the breath of life and hope to those who can see beyond the present moment.

“…when the holy Manifestation of God, Who is the Sun of the world of creation, casts His splendour upon the world of hearts, minds, and spirits, a spiritual springtime is ushered in and a new life is unveiled. The power of the matchless springtide appears and its marvellous gifts are beheld. Thus you observe that, with the advent of each of the Manifestations of God, astonishing progress was attained in the realm of human minds, thoughts, and spirits. Consider, for example, the progress that has been achieved in this divine age in the world of minds and thoughts—and this is only the beginning of the dawn! Erelong you will witness how these renewed bounties and heavenly teachings have flooded this darksome world with their light and transformed this sorrow-laden realm into the all-highest Paradise.”3Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions. Available at www.bahai.org/r/726404644. Note that the original text has been modified to reflect the newest translation of this work.

How great the blessedness that awaiteth the king who will arise to aid My Cause in My Kingdom, who will detach himself from all else but Me! Such a king is numbered with the companions of the Crimson Ark—the Ark which God hath prepared for the people of Bahá. All must glorify his name, must reverence his station, and aid him to unlock the cities with the keys of My Name, the omnipotent Protector of all that inhabit the visible and invisible kingdoms. Such a king is the very eye of mankind, the luminous ornament on the brow of creation, the fountain-head of blessings unto the whole world. Offer up, O people of Bahá, your substance, nay your very lives, for his assistance.1Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá”u’lláh, www.bahai.org/r/204457703

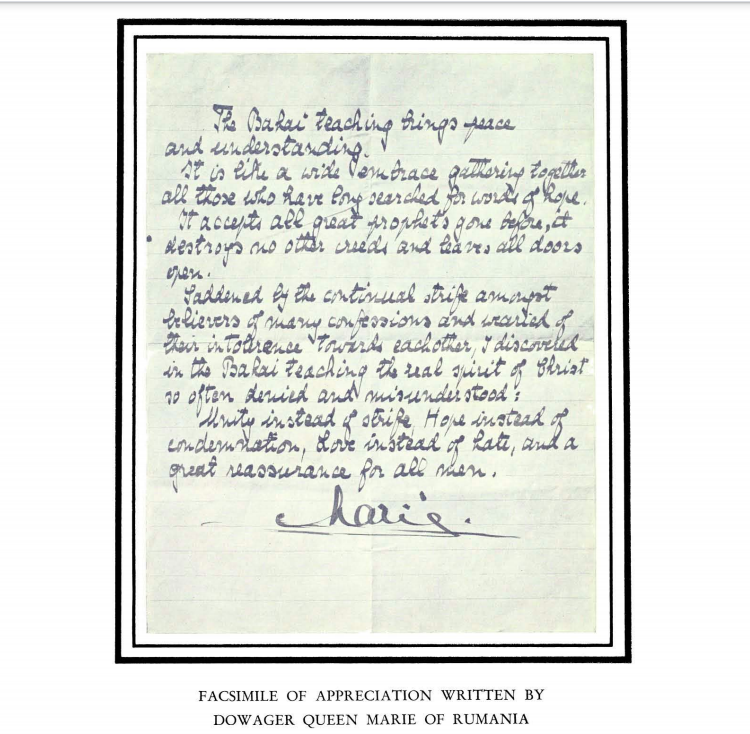

The first Queen of the world to study and to promote Bahá’u’lláh’s great Teachings has been Her Majesty Queen Marie of Rumania, one of the queens of this twentieth century who stands highest in intellect, in vision, in clear understanding of the new universal epoch now opening. Her Majesty received the book “Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era” by Dr. J. E. Esslemont and a note from the writer of this article who first visited Bucharest, Rumania, in January, 1926. The Rumanian Queen, grand-daughter of the renowned Queen Victoria of the British Empire and of Czar Alexander II of Russia, both of whom received Tablets from Bahá’u’lláh in their day, read this volume until three o’clock in the morning and two days later, on January 30, 1926, received me in audience in Controceni Palace, in Bucharest. Her first words after the greeting were, “I believe these Teachings are the solution for the world’s problems today!” The account of that historic morning appeared in “The Bahá’í Magazine” in Washington, in June, 1926, but very illuminating letters written by Her Majesty that same year show how deep was her confirmation. Here is one written to her loved friend Loie Fuller, an American then residing in Paris, which after these ten years can be published for the first time:

Lately great hope has come to me from one, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, a personal follower of Christ. Reading, I have found in His and His Father Bahá’u’lláh’s Message of Faith all my yearnings for real religion satisfied. If you ever hear of Bahá’ís or of the Bahá’í Movement which is known in America you will know what that is! What I mean, these books have strengthened me beyond belief and I am now ready to die any day full of hope; but I pray God not to take me away yet, for I still have a lot of work to do.

Other letters record that first of all she was teaching her young daughter Ileana about these beautiful truths. For ten years Her Majesty and her daughter, H.R.H. Princess Ileana (now Archduchess Anton), have read with interest each new book about the Bahá’í Movement as soon as it came from the press.

As we know she wrote three marvelous articles about these Bahá’í peace Teachings in 1926, and as they were syndicated each article appeared in nearly two hundred newspapers in the United States and Canada. Many millions of people were thrilled to read that a Queen had arisen to promote Bahá’u’lláh’s plan for universal peace. Quickly these articles were translated and published in Europe, China, Japan, Australasia and in the Islands of the seas.

Received in audience by Her Majesty in Pelisor Palace, Sinaia, in 1927, after the passing of His Majesty King Ferdinand, her husband, she graciously gave me an interview, speaking of the Bahá’í Teachings about immortality. She had on her table and on the divan a number of Bahá’í books, for she had just been reading in each of them the Teachings about Life after death. She asked the writer to give her greeting to Shoghi Effendi, to the friends in Írán and to the many American Bahá’ís who she said had been so remarkably kind to her during her trip through the United States the year before. Also, she graciously gave the writer an appreciation of these Bahá’í Teachings in her own hand-writing, for Volume IV. of the “Bahá’í World.”

Meeting the Queen again on January 19, 1928, in the Royal Palace in Belgrade, where she and H.R.H. Princess Ileana were guests of the Queen of Jugoslavia—and they had brought some of their Bahá’í books with them—the words I shall remember longest of all that Her dear Majesty said were these: “The ultimate dream which we shall realize is that the Bahá’í channel of thought has such strength, it will serve little by little to become a light to all those searching for the real expression of Truth.”

Another happy audience was in Her Majesty’s lovely summer palace “Tehna-Yuva,” at Balciĉ, on the Black Sea, in October, 1929. Again in the home of Archduchess Anton at Mödling near Vienna she and her mother received me on August 8, 1932, and in February, 1933, and Her Majesty made this great statement which was used as the frontispiece to “Bahá’í World,” Volume IV.:

Then in the audience in Controceni Palace on February 16, 1934, when Her Majesty was told that the Rumanian translation of “Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era” had just been published in Bucharest, she said she was so happy that her people were to have the blessing of reading this precious Teaching.

How beautiful she looked that afternoon—as always—for her loving eyes mirror her mighty spirit; a most unusual Queen is she, a consummate artist, a lover of beauty and wherever she is there is glory. Perhaps too, a Queen is a symbol, people like to have their Queen beautiful and certainly Queen Marie of Rumania is one of the most lovely in this world today. Her clothes, designed by herself, are always a “tout ensemble” creation so harmonious in colors they seem to dress her soul. She received me in her private library where a cheerful fire glowed in the quaint, built-in fireplace; tea was served on a low table, the gold service set being wrought in flowers. There were flowers everywhere, and when she invited me into her bedroom where she went to get the photograph which I like so much, as I saw the noble, majestic proportions of this great chamber with its arched ceiling in Gothic design, I exclaimed in joy, “Your room is truly a temple, a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár!” There were low mounds of hyacinths, flowers which Bahá’u’lláh loved and mentioned often in His Writings; there was a bowl of yellow tulips upon a silken tapestry in yellow gold, a tall deep urn of fragrant white lilacs, and an immense bowl of red roses. Controceni Palace is the most beautiful palace I have seen in any country in the blending of its colors and III its artistic arrangements.

Her Majesty is a writer as well as an artist, and Her Memoirs entitled “The Story of My Life” were just then being published in “The Saturday Evening Post.” She told me she writes two hours every morning unless her time is invaded by queenly duties, charity duties, family duties. She was pleased with the sincere letters that were pouring in from all continents giving appreciations of her story. She told me the American people are so open-hearted and that from the United States children, professors, farmers’ wives and the smart people had written to her, the tone in all their letters revealing Her Majesty’s entire sincerity and the deep humanity of her character. One teacher wrote Her Majesty that in her childhood each one lived through his own childhood: another said, “All who read your story have their own lives stirred!” The Queen remarked, “And this is a very satisfactory criticism for an author.”

A most pleasing letter had just arrived from Japan from a girl there who thanked God Who had allowed her to live in a period in which such a wonderful book had been written! “This,” said the Queen, “is one of the nicest appreciations I have ever heard.”

Then the conversation turned again to the Bahá’í Teachings and she gave a greeting to be sent to Shoghi Effendi in Haifa. Later she mentioned an incident in Hamburg when she was en route to Iceland in the summer of 1933. As she passed through the street, a charming girl tossed a little note to her into the motor car. It was: “I am so happy to see you in Hamburg, because you are a Bahá’í.” Her Majesty remarked that they recognized a Bahá’í and this shows a spirit of unity in the Bahá’í Movement.

Her Majesty said to me, “In my heart I am entirely Bahá’í,” and she sent me this wonderful appreciation: “The Bahá’í Teaching brings peace to the soul and hope to the heart. To those in search of assurance the Words of the Father are as a fountain in the desert after long wandering.”

And now today, February 4, 1936, I have just had another audience with Her Majesty in Controceni Palace, in Bucharest. As I was starting to walk up the wide ivory toned stairs carpeted with blue Iranian rugs to the third floor suites, at that very moment over a radio came the rich strains of the Wedding March from “Lohengrin,” played by an orchestra. It seemed a symbol: the union of spiritual forces of the East and Europe! Again Queen Marie of Rumania received me cordially in her softly lighted library, for the hour was six o’clock. She was gowned in black velvet and wore her great strands of marvelous pearls. The fire in the grate beamed a welcome with its yellow-glowing fragrant pine boughs and large bowls of yellow tulips adorned the apartment.

What a memorable visit it was! She told me she has a friend in ‘Akka, Palestine, who knows Shoghi Effendi and this friend recently has sent her pictures of ‘Akka and Haifa; the two were playfellows when they were children and met in Malta. She also told me that when she was in London she had met a Bahá’í, Lady Blomfield, who had shown her the original Message that Bahá ‘u’llah had sent to her Grandmother Queen Victoria in London. She asked the writer about the progress of the Bahá’í Movement especially in the Balkan countries.

“Since we met two years ago,” said Her Majesty, “so many sad events have happened! I look on with a great deal of sorrow at the way the different peoples seem to misunderstand one another; especially now that I have become very lonely in my home, I have all the more time to think over these problems, and I’m sometimes very sad that I can do so little. However, I know that the right spirit and the right thoughts go a long way towards that unity of hearts which I haven’t given up the hope to see before I pass on.”

She spoke, too, of several Bahá’í books, the depths of “Íqán” and especially of “Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh” which she said was a wonderful book! To quote her own words: “Even doubters would find a powerful strength in it, if they would read it alone and would give their souls time to expand.”

Her Majesty kindly promised to write for “Bahá’í World,” Volume VI, a special appreciation and to send it after four days.

I asked her if I could perhaps speak of the broach which historically is precious to Bahá’ís, and she replied, “Yes, you may.” Once, and it was in 1928, Her dear Majesty had given the writer a gift, a lovely and rare brooch which had been a gift to the Queen from Her Royal Relatives in Russia some years ago. It was two little wings of wrought gold and silver, set with tiny diamond chips and joined together with one large pearl. “Always you are giving gifts to others, and I am going to give you a gift from me,” said the Queen smiling, and she herself clasped it onto my dress. The wings and the pearl made it seem “Lightbearing,” Bahá’í! It was sent the same week to Chicago as a gift to the Bahá’í Temple, the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár, and at the National Bahá’í Convention which was in session that spring, a demur was made-should a gift from the Queen be sold? Should it not be kept as a souvenir of the first Queen who arose to promote the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh? -However, it was sold immediately and the money given to the Temple, for all Bahá’ís were giving to the utmost to forward this mighty structure, the first of its kind in the United States. Mr. Willard Hatch, a Bahá’í of Los Angeles, California, who bought the exquisite brooch, took it to Haifa, Palestine, in 1931 and placed it in the archives on Mt. Carmel where down the ages it will rest with the Bahá’í treasures.

Inadequate as is anyone article to portray Her Majesty Queen Marie of Rumania’! splendid spiritual attitude, still these few glimpses do show that she stands strong for the highest Truth, and as an historical record they will present a little of what the first Queen did for the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh.

Much has been written of the journeys of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, ‘Abbás Effendi. Having been released from the prison fortress of ‘Akká, after forty years of captivity, he set himself to obey the sacred charge laid upon him by his Father, Bahá’u’lláh. Accordingly he undertook a three years’ mission into the Western World. He left the Holy Land and came to Europe in 1911.

During that and the two following years, he visited Switzerland, England, Scotland, France, America, Germany and Hungary.

When the days of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s first visit to London (in the autumn of 1911) were drawing to a close, his friends, Monsieur and Madame Dreyfus-Barney, prepared an apartment for his residence whilst in the French capital. It was charmingly furnished, sunny, spacious, situated in the Avenue de Camöens (No. 4) whence a flight of steps led into the Trocadero Gardens. Here the Master often took solitary, restful walks. Sheltered in this modern, comfortable Paris flat, he whom we revered, with secretary servitors and a few close friends, sojourned for an unforgettable nine weeks.

I shall try to describe some of the events which took place, but these events owe their significance to the atmosphere of otherworldliness which encompassed the Master and his friends.

We, at least some of us, had the impression that these happenings became, as it were, symbols of Sacred Truths.

Who is this, with branch of roses in his hand, coming down the steps? A picturesque group of friends – some Iránians wearing the kola, and a few Europeans following him, little children coming up to him. They hold on to his cloak, confiding and fearless. He gives the roses to them, caressingly lifting one after another into his arms, smiling the while that glorious smile which wins all hearts. Again, we saw a cabman stop his fiacre, take off his cap and hold it in his hands, gazing amazed, with an air of reverence, whilst the majestic figure, courteously acknowledging his salutation, passed by with that walk which a friend had described as “that of a king or of a shepherd.”

![]()

Another scene. A very poor quarter in Paris – Sunday morning – groups of men and women inclined to be rowdy. Foremost amongst them a big man brandishing a long loaf of bread in his hand, shouting, gesticulating, dancing.

Into this throng walked ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, on his way from a Mission Hall where he had been addressing a very poor congregation at the invitation of their Pastor. The boisterous man with the loaf, suddenly seeing him, stood still. He then proceeded to lay about him lustily with his staff of life, crying “Make way, make way! He is my Father, make way.” The Master passed through the midst of the crowd, now become silent and respectfully saluting him. “Thank you, my dear friends, thank you,” he said smiling round upon them. The poor were always his especially beloved friends. He was never happier than when surrounded by them, the lowly of heart!

Who is he?

Why do the people gather round him?

Why is he here in Paris?

Shortly before Bahá’u’lláh “returned to the shelter of Heaven,” He laid a sacred charge upon his eldest son, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (literally Servant of God, the Most Glorious). This charge was that he should carry the renewed Gospel of Peace and Justice, Love and Truth, into all lands, with special insistence on the translating of all praiseworthy ideals into action. What profit is there in agreeing that these ideals are good? Unless they are put into practice, they are useless.

![]()

I hope to indicate, albeit too inadequately, something of that Messenger, the “Trusted One,” who came out of an Eastern prison to bring his Father’s message to the bewildered nations of earth. During the Paris visit, as it had been in London, daily happenings took on the atmosphere of spiritual events. Some of these episodes I will endeavour to describe as well as I can remember them.

Every morning, according to his custom, the Master expounded the Principles of the Teaching of Bahá’u’lláh to those who gathered round him, the learned and the unlearned, eager and respectful. They were of all nationalities and creeds, from the East and from the West, including Theosophists, Agnostics, Materialists, Spiritualists, Christian Scientists, Social Reformers, Hindus, Súfís, Muslims, Buddhists, Zoroastrians and many others. Often came workers in various Humanitarian societies, who were striving to reduce the miseries of the poor.

These received special sympathy and blessing.

![]()

‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke in Iránian which was translated into French by Monsieur and Madame Dreyfus-Barney. My two daughters, Mary and Ellinor, our friend Miss Beatrice Platt, and I took notes of these “Talks” from day to day. At the request of the Master, these notes were arranged and published in English. It will be seen that in these pages are gathered together the precepts of those Holy Souls who, being Individual Rays of the ONE were, in divers times and countries, incarnated here on Earth to lead the spiritual evolution of human kind.

![]()

The words of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá can be put on to paper, but how describe the smile, the earnest pleading, the loving-kindness, the radiant vitality, and at times the awe-inspiring authority of his spoken words? The vibrations of his voice seemed to enfold the listeners in an atmosphere of the Spirit, and to penetrate to the very core of being. We were experiencing the transforming radiance of the Sun of Truth; henceforth, material aims and unworthy ambitions shrank away into their trivial obscure retreats.

![]()

‘Abdu’l-Bahá would often answer our questions before we asked them. Sometimes he would encourage us to put them into words.

“And now your question?” he said.

I answered, “I am wondering about the next world, whether I shall ask to be permitted to come back here to Earth to help?”

“Why should you wish to return here? In My Father’s House are many mansions—many, many worlds! Why would you desire to come back to this particular planet?”

![]()

The visit of one man made a profound impression upon us: “O ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, I have come from the French Congo, where I have been engaged in mitigating the hardships of some of the natives. For sixteen years I have worked in that country.”

“It was a great comfort to me in the darkness of my prison to know the work which you were doing.”

Explanations were not necessary when coming to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá!

![]()

One day a widow in deepest mourning came. Weeping bitterly she was unable to utter a word.

Knowing her heart’s grief, “Do not weep,” said ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, wiping away the tears from the piteous face. “Do not weep! Be happy! It will be well with the boy. Bring him to see me in a few days.”

On her way out, this mother said, “O my child! He is to go through a dangerous operation today. What can I do!”

“The Master has told you what to do. Remember his words: ‘Do not weep, it will be well with the boy. Be happy, and in a few days bring him to see me.’”

In a few days the mother brought her boy to the Master, perfectly well.

![]()

One evening at the home of Monsieur and Madame Dreyfus-Barney, an artist was presented to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

“Thou art very welcome. I am happy to see thee. All true art is a gift of the Holy Spirit.”

“What is the Holy Spirit?”

“It is the Sun of Truth, O Artist!”

“Where, O where, is the Sun of Truth?”

“The Sun of Truth is everywhere. It is shining on the whole world.”

“What of the dark night, when the Sun is not shining?”

“The darkness of night is past, the Sun has risen.”

“But, Master! how shall it be with the blinded eyes that cannot see the Sun’s splendor? And what of the deaf ears that cannot hear those who praise its beauty?”

“I will pray that the blind eyes may be opened, that the deaf ears may be unstopped, and that the hearts may have grace to understand.”

As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke, the troubled mien of the Artist gave place to a look of relief, satisfied understanding, joyous emotion.

![]()

Thus, interview followed interview. Church dignitaries of various branches of the Christian Tree came. Some earnestly desirous of finding new aspects of the Truth—“the wisdom that buildeth up, rather than the knowledge that puffeth up.” Others there were who stopped their ears lest they should hear and understand.

One afternoon, a party of the latter type arrived. They spoke words of bigotry, of intolerance, of sheer cruelty in their bitter condemnation of all who did not accept their own particular dogma, showing themselves obsessed by “the hate of man, disguised as love of God”—a thin disguise to the penetrating eyes of the Master! Perhaps they were dreading the revealing light of Truth which he sought to shed upon the darkness of their outworn ecclesiasticism. The new revelation was too great for their narrowed souls and fettered minds.

The heart of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was saddened by this interview, which had tired him exceedingly. When he referred to this visit there was a look in his eyes as if loving pity were blended with profound disapproval, as though he would cleanse the defiled temple of Humanity from the suffocating diseases of the soul! Then he uttered these words in a voice of awe-inspiring authority,

“Jesus Christ is the Lord of Compassion, and these men call themselves by His Name!

Jesus is ashamed of them!”

He shivered as with cold, drawing his ‘abá closely about him, with a gesture as if sternly repudiating their misguided outlook.

![]()

The Japanese Ambassador to a European capital (Viscount Arawaka—Madrid) was staying at the Hôtel d’Jéna. This gentleman and his wife had been told of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s presence in Paris, and she was anxious to have the privilege of meeting him.

“I am very sad,” said her Excellency. “I must not go out this evening as my cold is severe and I leave early in the morning for Spain. If only there were a possibility of seeing him!”

This was told to the Master, who had just returned after a long, tiring day.

“Tell the lady and her husband that, as she is unable to come to me, I will call upon her.”

Accordingly, though the hour was late, through the cold and the rain he came, with his smiling courtesy, bringing joy to us all as we awaited him in the Tapestry Room.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá talked with the Ambassador and his wife of conditions in Japan, of the great international importance of that country, of the vast service to mankind, of the work for the abolition of war, of the need for improving conditions of life for the worker, of the necessity of educating girls and boys equally.

The religious ideal is the soul of all plans for the good of mankind. Religion must never be used as a tool by party politicians. God’s politics are mighty, man’s politics are feeble.

Speaking of religion and science, the two great wings with which the bird of humankind is able to soar, he said, “Scientific discoveries have greatly increased material civilization. There is in existence a stupendous force, as yet, happily, undiscovered by man. Let us supplicate God, the Beloved, that this force be not discovered by science until Spiritual Civilization shall dominate the human mind! In the hands of men of lower material nature, this power would be able to destroy the whole earth.”