In 2013, as winter gave way to spring, a group of villagers in Bihar Sharif, some 1,100 kilometers east of Delhi, India, gathered together on the rooftop of one of their homes to discuss the purpose and function of a local Bahá’í House of Worship, for which the planning had recently begun. These families, friends, and neighbors were consulting about what it would mean for their community to have a Bahá’í Temple raised in their midst, dedicated to prayer and meditation, embracing all people equally, regardless of religious affiliation, background, ethnicity, gender, or caste. In a quiet moment, tears welled in the eyes of one elderly resident as he came to understand that his family would be welcome in this special place. For generations, he explained, they had been denied entry to temples.

Unique in its functioning as a universal place of worship, the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár (from the Arabic, meaning “dawning-place of the mention of God”) was founded by Bahá’u’lláh, Who described its role in society in His sacred writings. Within, there are neither idols nor pictures, neither clergy nor preaching, and no calls for contributions. There is no requirement for an intermediary between the worshipper and God. It is open for personal prayer, meditation, and reflection as well as for devotional programs where prayers and passages from sacred scripture are read aloud, chanted, or sung by adults and children, without instrumental accompaniment. There are no formulas to be followed, allowing for diverse expressions of devotion.

THE FIRST MASHRIQU’L-ADHKÁRS IN THE EAST AND WEST

Since the earliest days of the Faith, Bahá’ís have gathered together for collective worship, which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described as an embryonic expression of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. The world’s first Bahá’í House of Worship, in ‘Ishqábád, Turkmenistan, was raised on a parcel of land set aside years earlier at the instruction of Bahá’u’lláh and was fostered at every stage of its development by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Moved by news of the building of the Temple in ‘Ishqábád, the Bahá’ís in North America sought ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approval for a similar project on their continent, which was granted in 1903. The “Mother Temple of the West” at Wilmette, near Chicago, was completed 50 years later.

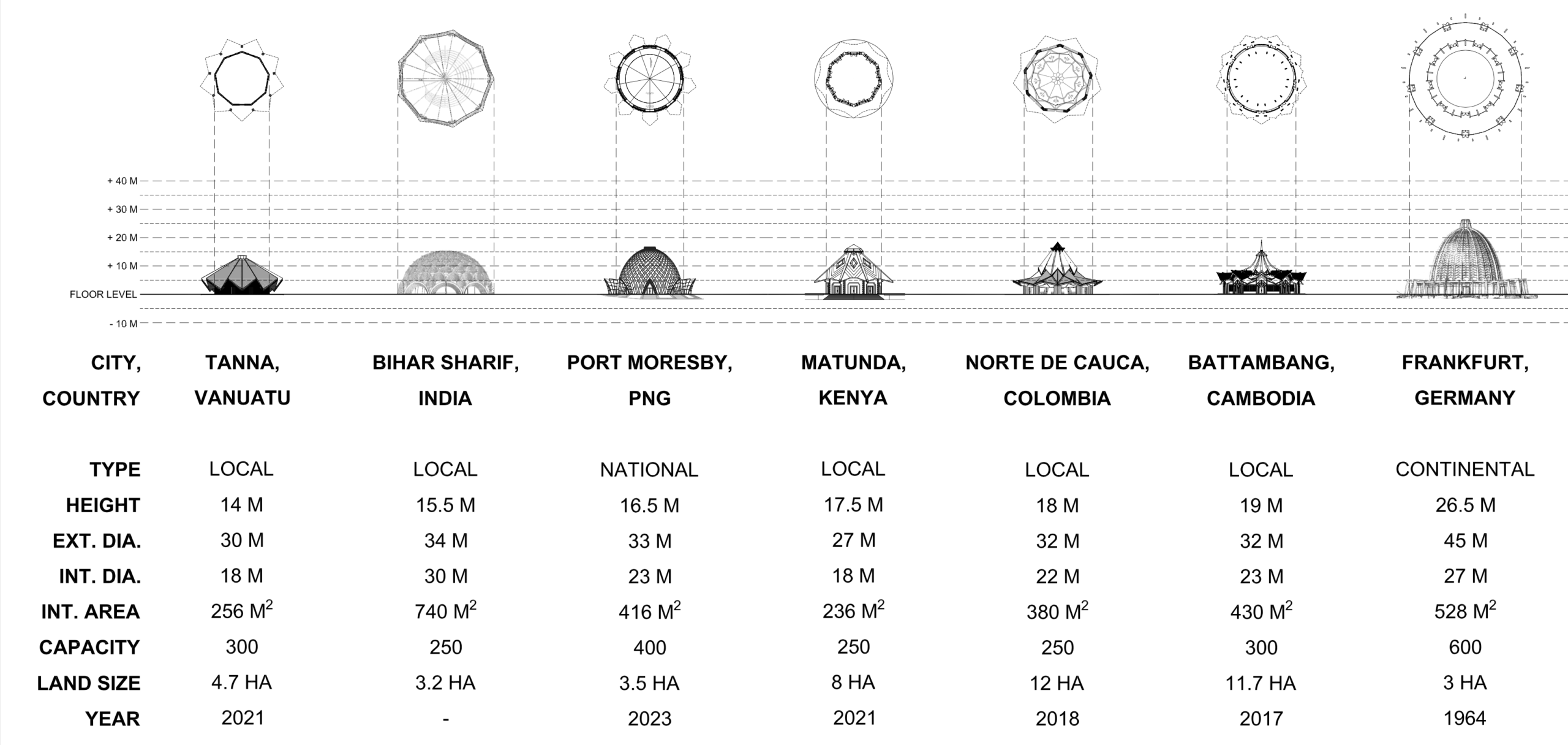

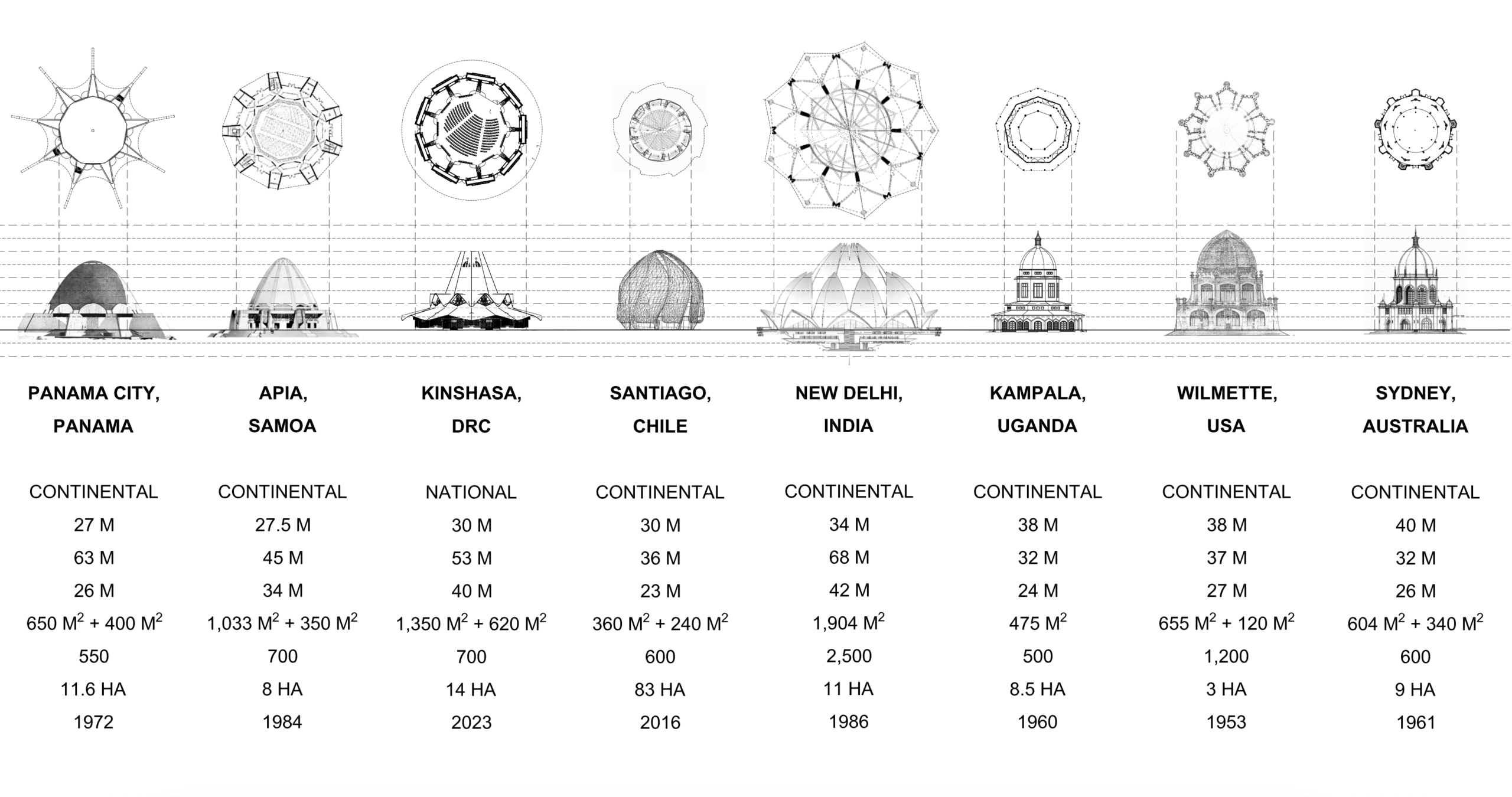

Upon completion of the House of Worship in the United States, Shoghi Effendi initiated two new processes: the construction of continental Temples, in Africa (Kampala, Uganda, completed in 1961), Australasia (Sydney, Australia, completed in 1961), and Europe (Frankfurt, Germany, completed in 1964); and securing land for Temples that would be built in the future. On 8 October 1952, Shoghi Effendi announced that the purchase of land for eleven future Bahá’í Houses of Worship would be an objective of the forthcoming decade-long Plan, along with the acquisition of the site for a future Mashriqu’l-Adhkár on Mount Carmel in the Holy Land. By 1963, some 46 sites for future Houses of Worship had been acquired. Continuing this opening stage of raising continental Temples, the Universal House of Justice proceeded with the building of Temples in Panama City, Panama (1972); Apia, Samoa (1984); and New Delhi, India (1986).

THE EMERGENCE OF NATIONAL AND LOCAL HOUSES OF WORSHIP

Pursuant to Bahá’u’lláh’s instruction “Build ye houses of worship throughout the lands in the name of Him Who is the Lord of all religions,”1The Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book, https://www.bahai.org/r/763968510 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá affirmed that Mashriqu’l- Adhkárs would “be established in every hamlet and city.”2Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, no. 55, https://www.bahai.org/r/681408626

As with all developments in the Bahá’í community, a deliberate and careful approach has been adopted in raising up Temples. For example, although the Temple site in ‘Ishqábád had been prepared for some 15 years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá waited until the means had been secured before permitting the construction to begin, so that the work could proceed without interruption.

In 1996, at the outset of the 25-year series of plans recently concluded, the Universal House of Justice described the elements of a flourishing community, highlighting the benefits of the practice of collective worship and regular devotional meetings to its spiritual life. However, as critical and transformative as individual and collective prayer may be, worship is not seen by Bahá’ís as an end in itself; rather, it ideally results in “endeavours to uplift the spiritual, social, and material conditions of society” and “deeds that give outward expression to that inner transformation.”3Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the world, 1 August 2013, https://www.bahai .org/r/980781985; Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of Iran, 18 December 2014, in The Institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár, https://www.bahai.org/r/250953299 These two inseparable aspects of Bahá’í life—worship and service—are expressed in the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár.

In one way, this expression can be seen through the role a House of Worship can play as the spiritual center of a community. People, turning their hearts to their Creator, pray and meditate within the Temple and find inspiration and spiritual strength to inspire their actions as they go about all aspects of their life, striving to make their contribution to their family and community. In another sense, the central edifice, in which people gather to pray, can be viewed as an aspect of the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. The process of raising up a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár will continue to develop to a stage where the central edifice will be surrounded by “dependencies dedicated to the social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific advancement of mankind.”4Universal House of Justice to the Bahá’ís of the world, 20 October 1983, https://www .bahai.org/r/346303577

In 2001, the Universal House of Justice announced plans to build the last continental Temple in Santiago, Chile. The House of Justice explained that a particular focus of that stage of the Bahá’í world’s development would include the enrichment of communities’ devotional life through the erection of national Houses of Worship.

Eleven years later, in April 2012, when the enterprise in Chile was well underway, the House of Justice announced plans to construct the first two national Houses of Worship in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Papua New Guinea, countries it had determined had experienced vibrant community-building endeavors. The House of Justice further announced that conditions were favorable for the launch of projects to build the first local Houses of Worship. The locations selected were Battambang, Cambodia; Bihar Sharif, India; Matunda Soy, Kenya; Norte del Cauca, Colombia; and Tanna, Vanuatu.

To support the construction of the new national and local Houses of Worship, the Universal House of Justice established two new entities at the Bahá’í World Centre: a Temples Fund to which Bahá’ís around the globe were invited to contribute, and the Office of Temples and Sites, to assist National Spiritual Assemblies whose countries had been selected.

THE COMMENCEMENT OF NATIONAL AND LOCAL TEMPLE PROJECTS

Shortly after the April 2012 announcement, National Spiritual Assemblies began to take practical steps to advance the projects. At the same time, Temple committees were established and began exploring strategies to stimulate awareness about the nature and purpose of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár and what it would mean for a community to house such an edifice. With a vision that the Temple would be for everyone, efforts were made to promote widespread participation among all the people whose lives would be directly impacted. Crucially, communities that had been developing the capacity to operate in a learning mode could now apply that capacity to the process of raising a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár.

Deliberations on the ideal features of Temple land required the balancing of practical and economic factors. This process, diligently undertaken, helped National Assemblies identify strategically located and accessible sites, thinking not only of prominence, but where regular visits to the House of Worship could naturally become part of a pattern of vibrant community life.

In countries where the national community had been in possession of a Temple site for decades, the suitability of the site was reassessed through the same lens. Architects were briefed about the design requirements of a Mashriqu’l-Adhkár—for example, that the House of Worship is nine-sided, circular in shape, and may have a dome. Design specifications called for simpler, more modest designs than those for the continental Houses of Worship. Yet, at the same time, architects would need to ensure that the building’s design would be beautiful and dignified, in harmony with its surroundings and with the cultural context where it would be constructed.

Where possible, local materials and building techniques drawing on generations of experience were given priority, as was an understanding of the native environment. While architects sought inspiration from the principles of the Bahá’í Faith, such as the oneness of humankind and the unity of religions, the design concepts were diverse, ranging from indigenous flowers and plants—for example, the lotus flower or cocoa fruit—to activities that form part of a culture’s identity, such as the practice of weaving. From the outset, the question of ongoing maintenance was carefully considered at the design stage, with the hope that Temples could mostly be maintained through the efforts of the local community.

Within a year of the completion of the Mother Temple of South America in Chile in October 2016, the local House of Worship in Battambang was dedicated in September 2017, followed by the Temple in Norte del Cauca in July 2018. As April 2021 approached, the Kenyan community prepared for the dedication of the local House of Worship in Matunda Soy. Progress continued in all designated locations; the construction of the Tanna Temple was at a late stage, and construction of the national Temples in Papua New Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo had begun. Initial steps to prepare the site in Bihar Sharif had commenced.

As of April 2021, national and local Temple projects ranged from roughly five to nine years from announcement to completion: Cambodia and Colombia within five to six years; Kenya in nine years; Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Democratic Republic of the Congo forecast for nine to eleven years; and India expected to be completed by 2024 or 2025. Construction has been the most consistent stage, ranging from one and a half to two and a half years. The process of land acquisition, at one and a quarter to seven years, and architect selection, at one and three quarters to almost eight years, seem to present the greatest opportunity for optimization, particularly by providing clearer parameters based on experience and simplifying approaches to engaging architects.

REFLECTIONS ON A NEW ERA

The development of the institution of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár during the period under review witnessed the completion of the last of the continental Temples—iconic structures that have, in part, symbolized the establishment of the Faith on all continents. An era has opened in which local and national Houses of Worship are emerging around the world. In such countries and cities where establishing a universally accessible place of worship seems to be a natural step in the development of community life, new opportunities and insights are galvanizing a process of community development already underway.

As Bahá’í communities have become more outwardly focused, planning for construction and operation of future Houses of Worship has begun to take on different dimensions. Those involved in managing the Temple complex and those coordinating community-building activities together are exploring what it means to have the Temple integrated into the pattern of community life. How does the relationship with a House of Worship move beyond the occasional special visit to being interwoven into one’s life, a place for regular meditation, reflection, and prayer? What conditions enable local inhabitants to see the Temple as “our” House of Worship? Do such questions also present an opportunity to revisit more traditional approaches to design and construction, through which they can be aligned to a greater degree with the transformative processes through which populations are taking greater ownership of their own spiritual, intellectual, and, ultimately, social and economic development?

Naturally, local Houses of Worship emerge in communities with burgeoning community-based social and economic development activities. As this process expands, so too will the opportunities to learn about the development of “dependencies dedicated to the social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific advancement of mankind,” a practical expression of the interconnection of worship and service.

On the horizon lies a period of discovery and development through which the influence of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár “on every phase of life” can be realized in ever greater measure.

The prestigious biennial Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) International Prize is not a typical architectural award.

An international jury of six highly distinguished architects has to choose a building that stands out for being “transformative within its societal context” and “expressive of the humanistic values of justice, respect, equality, and inclusiveness.” This they have to do from among an extraordinary selection of architectural structures from around the world that have impacted the social life of the communities within which they were built.

This year’s RAIC International Prize of $100,000 was awarded to the Bahá’í House of Worship for South America. The prize money is being dedicated to the long-term maintenance of the Temple. Commissioned by the Universal House of Justice and designed by Canadian architect Siamak Hariri, the House of Worship for South America has become an iconic symbol of unity for Santiago and well beyond. Overlooking the city from the foothills of the Andes, the Temple has received over 1.4 million visitors since its inauguration in October 2016. The House of Worship has not only symbolized unity but it has given expression to a powerful conviction that worship of the divine is intimately connected with service to humanity.

The connection between the built environment and the well-being of society was a preeminent concern for the Jury of the RAIC Prize. Diarmuid Nash, the Jury Chair, explains that three architectural projects were selected as finalists for the transformative impact they had on their respective communities. “The Bahá’í Temple was a community project. Numerous volunteers worked on this project, similar to a way a community project works in a small village, but this was on a global scale.”

“But the Temple went beyond the community,” he continues. “It extended the principles of the Bahá’í Faith—that every person is equal, that every person can come here to reflect and regenerate. It had this impact that rippled beyond the community and attracted more and more people from all walks of life.”

The process of selection was rigorous and extended over six months. Jury members were asked to perform site visits as part of their research and selection process. “We asked Stephen Hodder, former President of the Royal Institute of British Architects and guest Juror, to visit this project,” says Mr. Nash. “We thought he would have a dispassionate eye.”

Mr. Hodder visited the Temple for three days earlier this year and spent a significant amount of time with the local community. He later shared his impressions with the Jury, referring to the House of Worship as “truly transformational, timeless and spiritual architecture, the like of which I have never experienced, and the influence of which extends way beyond the building.”

Speaking about Mr. Hodder’s visit, Mr. Nash says “Stephen said to me that he had not felt such an emotional impact since he had walked into Ronchamp, which is a very famous chapel all of us have visited in our architectural careers. It is a touchstone of modern architecture. He said ‘this goes beyond Santiago, it reaches out to the world.’”

Mr. Hodder in his comments to the Jury shared the following thoughts:

“How can it be that a building captures the spirit of ‘unity,’ a sacred place, or command a prevailing silence without prompting? The interior space spirals upwards vortex-like culminating with the oculus within which is the inscription ‘O Thou Glory of the Most Glorious’. Seating orientates to Haifa and the Shrine of the Báb, the forerunner of Bahá’u’lláh…. But why do people flock to the Bahá’í Temple? Is it the garden, planted with native species and lovingly cared for by volunteers, or the view over Santiago and remarkable sunsets, or the curious object set against the mountains? The Temple is the anchor…At night, the opacity of the cast glass outer skin, and the translucency of the Portuguese marble inverts, and the dome appears to glow ethereally from the inside…. The Temple has not only afforded a focus for the Bahá’í community but in their commitment to ‘service’ also for the neighbourhood and its well being.”

It was not only the impact of the Temple on society but also the nature of its craftsmanship that struck the Jury. “It was lovingly assembled,” says Mr. Nash. “The woodwork, the stonework, and the glasswork—they all have the sense of a hand shaping them, which is remarkable for a project so sophisticated. This had a powerful impact on the Jury. There was this sense that the hand of the community had crafted the outcome.”

In the wake of the award, Mr. Hariri has been reflecting on the endeavour. “Hundreds of people sacrificially worked on this project with great dedication, enormous skill, and put themselves forward at the very frontier of what’s possible in architecture,” he explains.

“The Temple reflects an aspiration. What architects do is put into form aspiration. When you have a chance like this, where the aspirations are so great, it requires the furthest reaches of imagination to meet that challenge.”

The award was presented on 25 October at a ceremony at the Westin Harbour Castle in Toronto. “Above all,” said Mr. Hariri in remarks he made that evening, “our gratitude extends to the Universal House of Justice which was our unwavering source of guidance, courage, and constancy.”

Mr. Nash, who was there, says that as the talk finished people were standing and cheering. “We were all very inspired. It’s a project that has a life of its own. It is supposed to be a building built to last 400 years. I suspect it will go well beyond that.”

In Norte del Cauca, the land is blanketed by sugar cane plantations. They run for miles, under the watchful gaze of the Andes.

Scattered amid the expanse of monoculture fields, villages and small farms dot the terrain. In recent decades, these traditional farms and the lush greenery of the region have been largely overtaken by vast fields of sugar cane crop.

Here, in the village of Agua Azul, and in neighboring communities, people have been talking about the revival of the natural habitat. This conversation was catalyzed in April 2012, when it was announced that a Baha’i House of Worship was to be built here for the people of the region.

Over the period since the announcement, as the community has set out to prepare itself for this momentous development, a heightened consciousness of the nature and purpose of the House of Worship has given rise to an acute awareness about the physical environment and its relationship to the spiritual and social well-being of the population.

“There were several meetings early on, when plans for the Temple were announced,” explains Ximena Osorio, a representative of the Colombian Baha’i community. “People were inspired by the concept of the House of Worship, how it brought together devotion and service, how it was to be a place of worship for everyone.”

“Gradually, conversations arose about the types of trees and flowers that would surround the Temple,” says Ms. Osorio. “They wanted the landscape to capture the beauty and diversity of the region.”

Over time, the conversation evolved. “An idea emerged,” continues Ms. Osorio. “We would grow a native forest on the land surrounding the Temple site. ”

The idea took root, and a team coalesced around the project.

Hernan Zapata, affectionately referred to within the community as “Don Hernan”, recently joined the initiative. A traditional farmer from the neighboring village of Mingo, he has worked the land his entire life.

Today, his is one of the remaining traditional farms in the region, and many of the species which are found on his land have all but disappeared in surrounding areas. His land provides a glimpse into the rich ecological diversity that had characterized Norte del Cauca only decades ago.

“The truth is that Norte del Cauca was once an immense forest,” explains Don Hernan. “But all of that has been destroyed. Now none of it exists.”

“One thing I want with this project,” he explains, “is that new generations should know what once existed. This native forest that we are going to grow should be a school, should be a place of learning.”

The project has captured the imagination of many others in the region as well. Throughout neighboring villages, individuals have begun to donate seeds and plants that can be grown on the land around the Temple site and in a greenhouse that has been built for the project by local volunteers.

Contributions have included indigenous species, such as the rare “Burilico” tree, which is near extinction in the region.

For Gilberto Valencia, a local factory worker and member of the project team, this initiative has connected him to his family history in Norte del Cauca.

“I’ve always been very motivated to know more about the land and about farming because, while I am not a farmer, I come from a long line of farmers. My father and his father always had a farm that they cultivated for the subsistence of the family, and for the sale of goods to others.”

The project inspired Mr. Valencia, who is married and a father, to begin studying environmental engineering.

“When I began working on the land surrounding the House of Worship, I felt at that moment, that the thing that we were going to build was going to change the natural environment,” he said. “This is a chance to change the destiny of the region.”

Mr. Valencia now works on the project alongside his ten year old son, Jason, the project team’s newest and youngest member.

In recent months, Jason has found himself immersed in the project, helping to transplant seeds and saplings to the temple site and working alongside his father to cultivate and protect the surrounding land.

“I have learned about trees I never knew existed,” says Jason, speaking about his experience. “I love working with my father on this project because, together, we’re going to revive many of the plants that have been lost.”

For Alex Hernan Alvarez, a resident of Agua Azul and member of the project team, what is happening in the village has profound implications for the children.

“Here, in Norte del Cauca, we don’t have land or spaces like this, open for everyone. I have three children, and it is very gratifying for me to think that I will leave something for them,” says Mr. Alvarez.

“Knowing that a verdant forest and magnificent House of Worship will bloom for future generations inspires in me a profound sense of dedication.”

Speaking of one of the indigenous trees of the region – the ‘Saman’ tree – Mr. Alvarez states, “The Saman is a traditional tree, beautiful and large. When my children go to the land to pray, they will have a place to sit, under that tree. This motivates me every day. This brings me joy.”

While the House of Worship is not yet built, in many important ways, it is already carrying out its purpose, inspiring the inhabitants of the region to connect with the sacred and reach for greater heights of service to their communities.

“The idea of the Temple, what it represents,” says Ms. Osorio, “is in itself cultivating in all of us – children, youth and adults – an appreciation for the importance of a life centered around worship of God and service to humanity.”