In country after country, the bicentenary of the Birth of the Báb has been celebrated by people representing the rich diversity of the human race, giving rise to countless expressions of art, music, and acts of selfless service in honor of His life and teachings. As part of the efflorescence of activities during this period, Romanian artist Simina Boicu Rahmatian has prepared twenty-five illustrations that depict some of the most significant sites related to the brief but stirring history of the Bábí Faith. The hand-drawn illustrations that follow invite us to immerse ourselves in the “marvelous happenings that…heralded the advent of the Founder of the Bábí Dispensation, the dramatic circumstances of His own eventful life, the miraculous tragedy of His martyrdom, the magic of His influence exerted on the most eminent and powerful among His countrymen.”1Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh [US Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1991] 124 The sepia tones transport us back to the nineteenth century. The contrast between light and shadow brings to life the buildings, towns and landscapes that form the backdrop against which a new religion came into existence. Yet, these images are seldom accompanied by the silhouettes of human beings; it is we the viewers who are invited to step into those scenes and imagine the settings and circumstances in which an extraordinary chapter of humanity’s spiritual evolution unfolded.

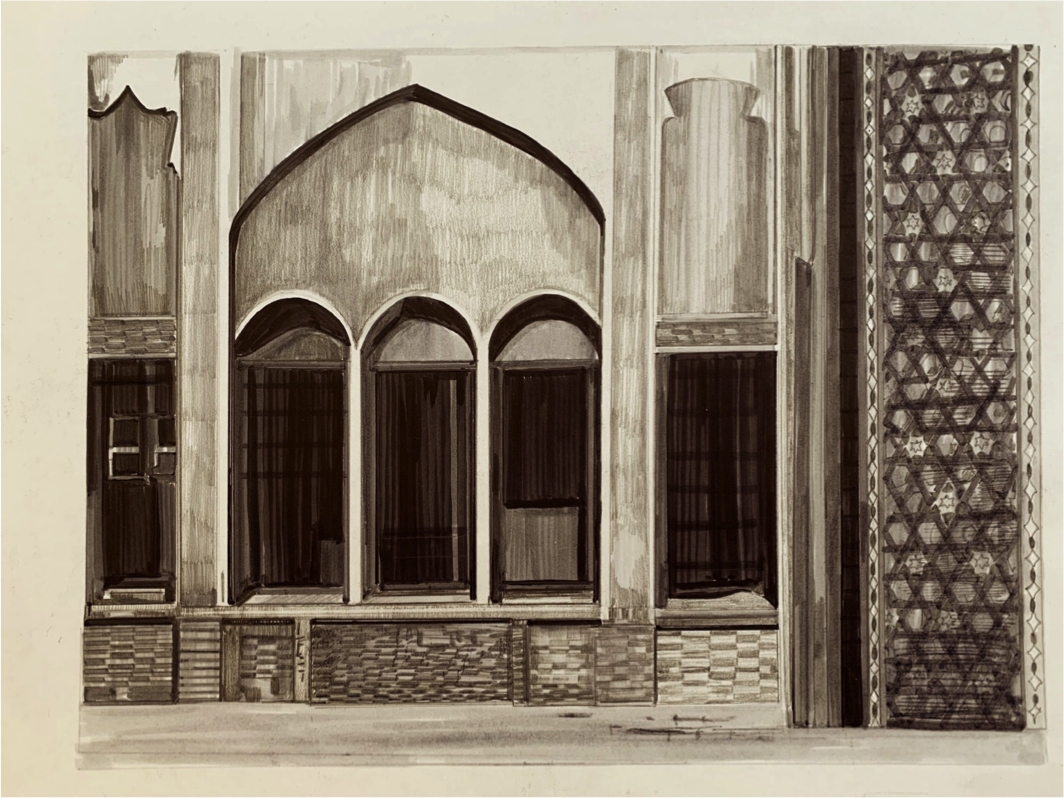

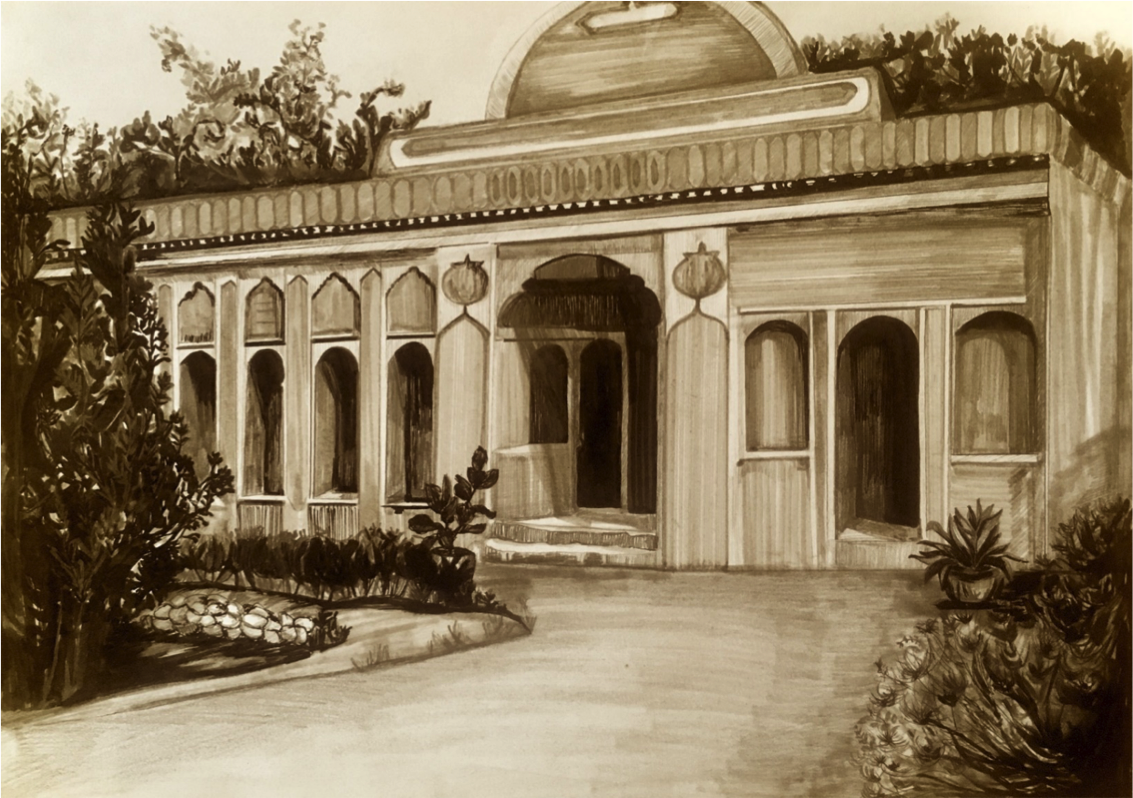

Some of the illustrations depict historic Oriental edifices: the Shrine of the Imám Ḥusayn in Karbala (no. 5), a well-known mosque and marketplace in Baghdad (no. 10), and the Masjid-i-Vakíl of Shiráz (no. 11). Also depicted are settings of sites more specifically associated with Bábí history: The front door of the Báb’s house in Shiráz (no. 3) is shut before our eyes, but our minds are invited in to imagine that fateful evening of May 22, 1844, when the Báb announced to His first disciple that He was the Promised One of Islam and the Gate (Báb, in Arabic) to a new age for humankind. While looking at the desolate castles of Máh-kú and Chihríq (nos. 14 and 15), where the Báb was imprisoned from 1847 to 1850, we are reminded of His isolation and deprivation; as He wrote, “there is not at night even a lighted lamp.”2Selections from the Writings of the Báb [Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978] 87 The sun-drenched barrack square of Ṭabríz (no. 20), where the Báb was executed, calls to our minds that unique historic moment when He, the target of hundreds of bullets, was nowhere to be found after the thick cloud of smoke cleared. Thousands, crowded around the city square, witnessed that remarkable scene. Other pictures remind us of the heroism of tens of thousands of His followers who courageously advanced a Cause that was destined to change the world. We visit the Sabzih-Maydán of Tehran (no. 18), where a young Iranian met his death singing a couplet from Rúmí: “In one hand the wine-cup, in one hand the tresses of the Friend. Such a dance in the midst of the market-place is my desire!“3Edward G. Browne, ed., A Traveller’s Narrative [Cambridge University Press, 1891] 333-4, Note T We stand before Tehran’s Gate of Naw (no. 22), on whose sides the remains of many of the Bábís were hung. We reflect somberly at Zanján’s square (no. 21), another theater of a terrible slaughter.

In the opening and concluding scenes of the collection, the artist portrays the cypress grove located at the south side of the Shrine of the Báb. The first image (no. 1) depicts the grove as seen from below in the early 1900s; the final image (no. 25) is the view from above that we see today. In the former, we can imagine Bahá’u’lláh standing beside the grove and instructing ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to house the remains of the Báb in the land just below those trees. In the latter, we see Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of the Shrine of the Báb realized in “the Queen of Carmel enthroned on God’s Mountain, crowned in glowing gold, robed in shimmering white, girdled in emerald green, enchanting every eye from air, sea, plain and hill.”4Shoghi Effendi, Messages to the Baha’i World – 1950-1957 [Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971] 169

In the visual journey ahead, we find the embodiment of these poignant words written by Shoghi Effendi in 1944:

We behold, as we survey the episodes of this first act of a sublime drama, the figure of its Master Hero, the Báb, arise meteor-like above the horizon of Shíráz, traverse the sombre sky of Persia from south to north, decline with tragic swiftness, and perish in a blaze of glory. We see His satellites, a galaxy of God-intoxicated heroes, mount above that same horizon, irradiate that same incandescent light, burn themselves out with that self-same swiftness, and impart in their turn an added impetus to the steadily gathering momentum of God’s nascent Faith.5Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By [Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974] 3

As the world endures a period of heightened crisis, may we be reminded of the extraordinary Figure of the Báb, Who was able to “illuminate a society and an age shrouded in darkness.”6October 2019 message of the Universal House of Justice to all who have come to honour the Herald of a new Dawn

Credit: Simina Boicu

Credit: Simina Boicu

One of the most inspiring things about Nabíl’s Narrative, The Dawn-Breakers, is that it creates, not alone a background of knowledge and authenticity in which to set the Bahá’í Cause in its present world-wide expression, nor just a key to a way

of living and being that we in the West had almost forgotten was possible to the human race, (latent indeed within their seed of humanness), but opens before us a stage which was a nation and an epoch in history, on which a pageant of romance, of adventure and heroism unequaled by any crusade plays itself before us. And slowly as we become more en rapport with the thought and mode of expression of Nabíl, that pageant and its figures begin to take hold on us, to live for us as realisms; or perhaps something deeper still, we take hold of them and, inspired by their deeds and the lofty atmosphere of their lives, try to carry out into our own far Western World that same banner of shining belief and inner conviction that they raised aloft in Persia not eighty years ago.

The mere sound of their names is music to us; their faces, in which the light of their actions shone so brightly, become stars in the new world dawn, casting forever their radiance upon the path of men. The dusty roads of Persia, winding amidst its rocky hills and wind and heat-swept plains, become familiar highways in our minds down which we follow, with love and tender adoration, the green-turbaned, slight figure of the Báb led by his cavalcade of guards who loved Him so devotedly they begged Him to escape from their custody. Or we accompany Qurratu’l-‘Ayn in her howdah, travelling from city to city and raising a call no woman had ever dared to proclaim before in the lands of her bondage. Or it is after the hoofs of Mullá Husayn’s horse that we speed, hearing him cry, Yá Sáhibu’z-Zamán!

shaking the very walls of our hearts.

In Nabíl we partake of the food of Beauty, a rare thing in a world grown clouded with strife, terror and sadness. We see the days rise under the light of a heavy golden sun, in a land where the weight of its heat falls on the world like a tangible cloak; we await the nights under an Eastern sky where when the moon is absent a million stars hang low to light your way, and when the moon is present she eclipses in white light all but her own deep and mysterious shadows. Against these settings rise the nineteen Letters of the Living.

The first, the Báb. No one person could attempt an adequate description of that blessed Youth, but through the book run testimonies of Him, as though He were a wind in the tree of humanity and the voices of the leaves each gave their separate praise to Him. … His countenance revealed an expression of humility and kindliness which I can never describe.

Every time I met Him, I found Him in such a state of humility and lowliness as words fail me to describe; His downcast eyes, His extreme courtesy, and the serene expression of His face made an indelible impression upon my soul.

The sweetness of His utterance still lingers in my memory.

The melody of His chanting, the rhythmic flow of the verses which streamed from His lips caught our ears and penetrated into our very souls …. Our hearts vibrated in their depths to the appeal of His utterance.

Not alone did every bearing of that One give forth testimony of His station, but His walk was sufficient for Quddús to distinguish Him. Why seek you to hide Him from me?

he exclaimed. I can recognize Him by His gait. I confidently testify that none besides Him, whether in the East or in the West, can claim to be the Truth. None other can manifest the power and majesty that radiate from His holy person.

After passing from one persecution to another, and prison to prison, always with that surpassing meekness of mien, the glory of the light within Him was turned like a beacon upon the world when He declared His station to the ‘ulamás of Tabríz at His trial. He entered that room where all were arrayed against Him, and they were but the symbols of the nation which would at length kill Him and seek to hound from the earth His teachings and His followers, and that nation in turn was only the voice of a darkened world which perished from His light. And yet, the majesty of His gait, the expression of overpowering coherence which sat upon His brow—above all, the spirit of power which shone from His whole being, appeared to have for a moment crushed the soul out of the body of those whom He had greeted. A deep, a mysterious silence, suddenly fell upon them. Not one soul in that distinguished assembly dared breathe a single word. At last the stillness which brooded over them was broken by the Nizámu’l-Ulamá’. Who do you claim to be, he asked the Báb, and what is the message which you have brought?I am, thrice exclaimed the Báb, I am, I am, the promised One! I am the One whose name you have for a thousand years invoked, at whose mention you have risen, whose advent you have longed to witness, and the hour of whose Revelation you have prayed God to hasten. Verily I say, it is incumbent upon the peoples of both the East and the West to obey My word and to pledge allegiance to My person.

Thus did God’s paean rise in this greatest dawn of history, summoning a world to the shores of His Communion. In Bahá’u’lláh’s own Words: Nigh unto the celestial paradise a new garden hath been made manifest, round which circle the denizens of the realm on high and the immortal dwellers of the exalted paradise. Strive, then, that ye may attain that station, that ye may unravel from its wind-flowers the mysteries of love and know from its eternal fruit the secret of divine and consummate wisdom.

What was the fragrance of those windflowers

? No faint perfume of abstinence, no celibate fragrance that retired from the world, but a deep and abiding passion of being. A love that burned like a fire in the hearts of the souls and they became as stubble in its flame. Their lives were romance, sacrifice, love, and a deep and mysterious joy. Were they not—those who bared their breasts to the seen and unseen shafts of the enemy—like that whale of love that swallows up the seven seas and says, Is there yet any more?

and like that lover—thou wilt see him cool in fire and find him dry even in the sea.

When the heroes of Shaykh Tabarsí had been reduced to starving to death on the bone dust of their horses, grass, and their saddle and shoe leather, did not Quddús say, while rolling a cannon-ball scornfully with his foot: How utterly unaware are these boastful aggressors of the power of God’s avenging wrath! … Fear not the threats of the wicked, neither be dismayed by the clamour of the ungodly.

Then he continued saying that no power on earth could hasten or postpone the hour of their death, but should they allow themselves for one moment to become afraid they would have cast themselves out of the stronghold of Divine protection. Bahá’u’lláh said: My love is My stronghold; he that entereth therein is safe and secure, and he that turneth away shall surely stray and perish.

When we have followed Nabíl’s Narrative to the last of its multiple truths, histories and wisdoms, we find that the key to it, to the lives of those early Bábí martyrs, nay to the Cause of the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh, is summed up in the mystery of love. Their love was their indomitable and miraculous strength, their shining armour of protection, the diadem of their faith, the blood in which they pledged their eternal Beloved—that One for whom the heart of the world has ever languished and sought.

Nabíl becomes a lyric poet in those lines in which he describes the love of Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb. The Báb, whose trials and sufferings had preceded, in almost every case, those of Bahá’u’lláh, had offered Himself to ransom His Beloved from the perils that beset that precious Life; whilst Bahá’u’lláh, on His part, unwilling that He who so greatly loved Him should be the sole Sufferer, shared at every turn the cup that had touched His lips. Such love no eye has ever beheld, nor has mortal heart conceived such mutual devotion. If the branches of every tree were turned into pens, and all the seas into ink, and earth and heaven rolled into one parchment, the immensity of that love would still remain unexplored, and the depths of that devotion unfathomed.

Our minds turn to Mullá Husayn, who, mounted at the head of two hundred companions, bearing the prophesied Black Standard of Muhammad, and wearing the Báb’s green turban, held at Bay the combined armies of the Sháh for eleven months. Riding out in the teeth of twelve thousand men and crying, O Lord of the Age,

he and the invincible host of God’s followers dispersed the terrified enemy. At length he shed his blood at Quddús’ feet whilst speaking of the depths of the Sea of Revelation and their beloved Báb, ere his life ebbed away.

Or we remember Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, beautiful and famous, who escaped clandestinely from her own home in which her husband had imprisoned her in his opposition to her Bábí Faith, leaving her children motherless and making their father her bitterest enemy, to arise and proclaim throughout Persia and ‘Iráq the glory of the New Day. She created such a furor throughout the East that E. G. Browne was compelled to pay her one of the most glowing tributes woman has ever received. The appearance of such a woman as Qurratu’l-‘Ayn is in any country and any age a rare phenomenon, but in such a country as Persia it is a prodigy—nay, almost a miracle. Alike in virtue of her marvellous beauty, her rare intellectual gifts, her fervid eloquence, her fearless devotion, and her glorious martyrdom, she stands forth incomparable and immortal, amongst her countrywomen. Had the Bábí Religion no other claim to greatness this were sufficient—that it produced a heroine like Qurratu’l-‘Ayn.

The queenly names of history fade before the unveiled beauty of her whom the tongue of power hath named Tahirih—the pure one.

That moment, when, with one gesture of freeing herself and all women from the veils of weakness, inferiority, and submission, Qurratu’l-‘Ayn and the Bábí men unveiled, is unrivaled and has no precedent. Some turned from her bared face and doubted the Messenger of God because of tradition; one old man, unable to bear the age in which he found himself, attempted suicide; Quddús was spellbound with indignation; but Qurratu’l-‘Ayn cast her glance towards Bahá’u’lláh, who had named her Tahirih,

and said: Verily, amid gardens and rivers shall the pious dwell in the seat of truth, in the presence of the potent King. … This day is the day of festivity and universal rejoicing, the day on which the fetters of the past are burst asunder. Let those who have shared in this great achievement arise and embrace each other.

And they feasted together in the tent of Bahá’u’lláh, surrounded by the beautiful gardens of Badasht.

The same quality of beauty and majesty pervades all the events chronicled by Nabíl; sincerity is all that is required to become deeply and permanently inspired by the record contained in The Dawn-Breakers, for no heart who loved truth could read its history unmoved and remain unchanged. Here one tastes again those living waters

that alone can revivify mankind and nurture in him the seed of immortality.

Even the humblest of souls won undying glory, like that man who, seated in the bazaars of Isfáhán, heard the proclamation of the Báb’s message while sifting his wheat, and instantly and unhesitatingly accepted it. Later he hastened, sieve in hand, to join the heroes of Tabarsí, saying, With this sieve which I carry with me I intend to sift the people in every city through which I pass. Whomsoever I find ready to espouse the Cause I have embraced, I will ask to join me and hasten forthwith to the field of martyrdom.

Of all the wise and devout of that city he alone received the crown of a martyr’s fame.

And there was that heart-shattered boy who, when in Tabríz, heard of the Blessed Báb, longed to speed to Him and offer his life in the lists of His followers, and was imprisoned by his family who thought that if not already bewitched, one glimpse of the Báb would enchant him permanently as it did thousands. Inconsolable, he languished and pined for the only expression that could ever satisfy his pure young soul. The agony of his longing was rewarded when in a vision he saw the Báb, who addressed to him these words: Rejoice, the hour is approaching when, in this very city, I shall be suspended before the eyes of the multitude and shall fall a victim to the fire of the enemy, I shall choose no one but you to share with me the cup of martyrdom. Rest assured that this promise I give you shall be fulfilled.

A few years later it was this youth’s head that rested on the heart of the Báb as they hung bound from the walls of the barrack square of Tabríz, and it was his flesh that was inextricably interwoven with the Báb’s remains after their joint execution.

To some Nabíl will be a fascinating historical document. To others, great literature. Some will feel crushed by the tragedy of the brutally sacrificed lives of thousands. Others will be exalted by the knowledge that again the human soul has risen to its greatest heights and men have died immortal deaths. But to all of these its more subtile fragrance will be lost. Only those who have through some experience in life touched to their lips the cup of divine love, will fully grasp the purport of this mighty pageant. They will know why the martyrs sometimes sang when being led to execution: So hath overcome that scarce he knows Whether at the feet of the Beloved It be head or turban which he throws!

And they, becoming fired with that same zeal that pervaded those Dawn-Breakers, will carry on and establish that vision of hope for the world, for which they died.