A moving meditation penned by the Báb during His imprisonment in Máh-Kú, in the mountains of Azerbaijan, praises God for having turned a prison fortress into a noble chamber and an oppressive mountain into a heavenly garden. It reads:

How can I praise Thee, O Lord, for the evidences of Thy mighty splendor and for Thy wondrous sweet savors which Thou hast imparted to Me in this fortress … Thou hast watched over Me in the heart of this mountain where I am compassed by mountains on all sides. One hangeth above Me, others stand on My right and My left and yet another riseth in front of Me … Having suffered Me to be cast into the prison, Thou didst tum it into a garden of Paradise for Me and caused it to become a chamber of the court of everlasting fellowship.1The Báb, Selections from the Writings of the Báb (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1983), pp. 183- 84. Available at www.bahai.org/r/864833549

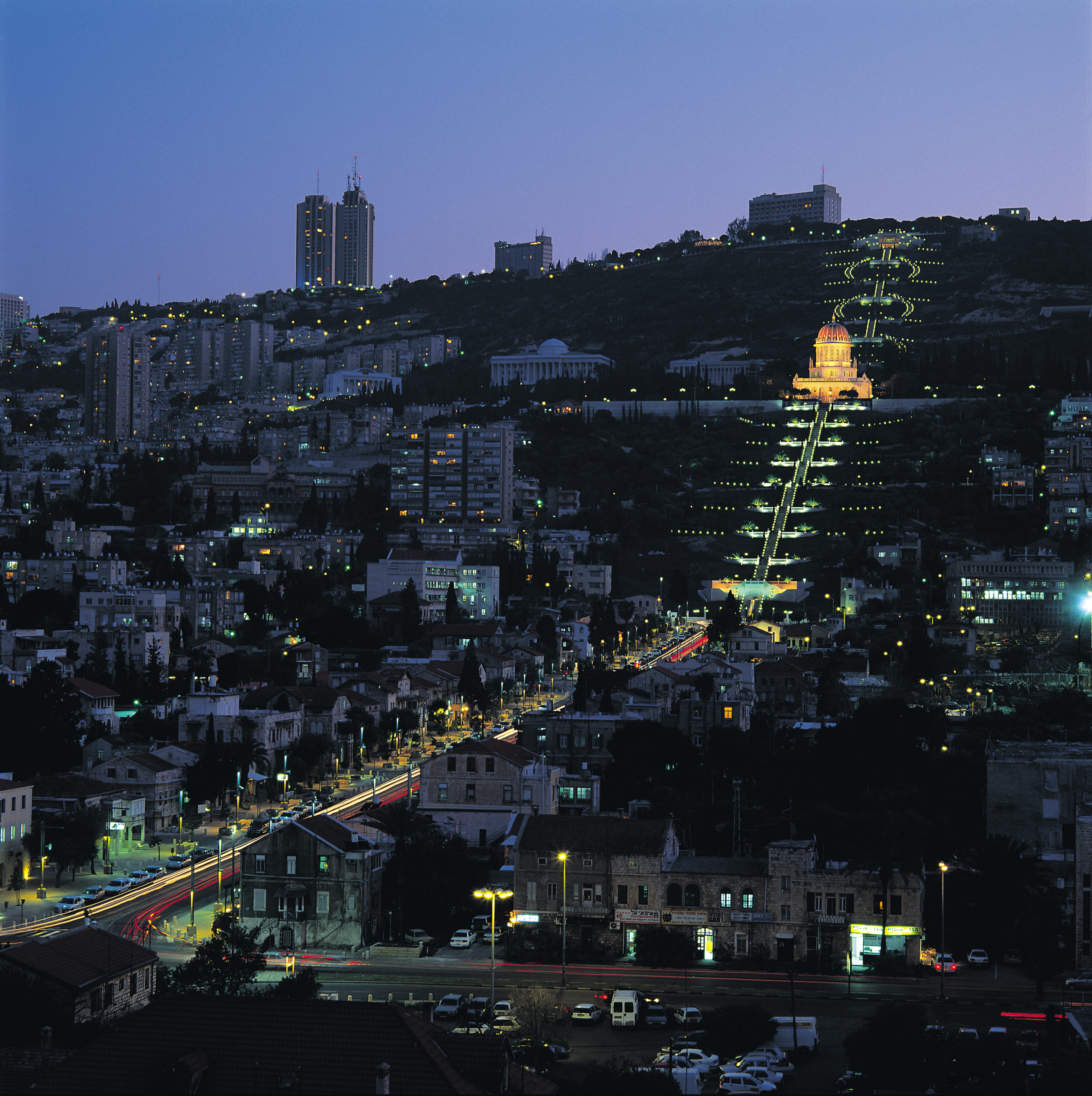

The terraces surrounding the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel in Haifa, which are nearing completion, are a powerful reminder of this transformation and thus a fitting means of paying tribute to the Báb and for enhancing the beauty of the resting place of His earthly remains. But in addition to effecting the transformation of a once barren and rocky mountain into a verdant, blooming garden, the nineteen terraces also symbolize another kind of change. In the words of the Universal House of Justice in a letter regarding the significance of these monumental edifices, “The beauty and magnificence of the Gardens and Terraces … are symbolic of the nature of the transformation which is destined to occur both within the hearts of the world’s people and in the physical environment of the planet.”2Letter of the Universal House of Justice to all National Spiritual Assemblies, 4 January 1994. Available at www.bahai.org/r/283913957

Visions of Paradise

The terraced gardens on Mount Carmel conjure up, for many of those who walk through them, images of the Garden of Eden, of paradise as it is described in various religious traditions. In Biblical Eden, “out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. And a river went out of Eden to water the garden.”3Genesis 2:9- 10, The Bible, King James Version. In the Qur’an, it is promised that in paradise, “the righteous shall drink of a cup tempered at the Camphor Fountain, a gushing spring at which the servants of God will refresh themselves … Reclining there upon soft couches, they shall feel neither the scorching heat nor the biting cold. Trees will spread their shade around them, and fruits will hang in clusters over them.”4Qur’an 76:8- 9, trans. N.J. Dawood. The influence of this vision of paradise is evident in traditional Persian gardens, which had “one central unifying purpose: praise of the Divine.”5Julie Scott Meisami, “Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (1985), p. 242. In fact, the word paradise itself “derives from the old Persian word pairidaeza … which meant the royal park, enclosure, or orchard of the Persian king.”6Julie Scott Meisami, “Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (1985), p. 231.

running water. . . and a pool to reflect the beauties of sky and garden; trees of various sorts, some to provide shade merely, and others to produce fruits; flowers, colorful and sweet-smelling; grass, usually growing wild under the trees; birds to fill the garden with song; the whole cooled by a pleasant breeze. The garden might include a raised hillock at the centre … often surmounted by a pavilion or palace.7Julie Scott Meisami, “Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (1985), p. 231.

This could almost serve as a description of the gardens on Mount Carmel. Here one’s eyes are indeed delighted by the sight of every kind of tree and flower, and one’s ears soothed by the murmur of running water and the song of birds. And at the center, more majestic than any palace, stands the golden-domed Shrine of the Báb, dedicated to the praise of God. As in Eden, where Adam and Eve “heard the voice of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day,”8Genesis 3:8, The Bible, King James Version many feel that this, too, is a place where God can be found. The terraces are, indeed, as Howard Adelman has described them, “the approach to a sacred place.”9Howard Adelman, narrating, “Bahá’í Hanging Gardens.” Television program, first broadcast on Israel Today, Canada, 6 December 1999.

However, as Louis Greenspan points out in a perceptive commentary on the locales of religious expression, in the Bible the garden is never an unmixed blessing. Eden is the archetypal garden for which humanity longs, but it is also the place of temptation, fall, and expulsion. The hanging gardens of Babylon—literally, “the Gate of God”- were considered to be one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, but they are associated on the one hand with sensual pleasure and on the other with the labor of slaves, among them captive and exiled Jews. Another Biblical garden, Gethsemane, is the scene of Christ’s agony and His betrayal. “The garden by itself is not paradise; the city is also needed with its energy,” says Greenspan.10Louis Greenspan on “Bahá’í Hanging Gardens.” Television program, first broadcast on Israel Today, Canada, 6 December 1999. And indeed, the ideal city is a parallel and related theme in religious traditions as well as in secular visions of the world. It finds expression in disciplines as different as religious millennialism, utopian literature, and urban planning.

The Ideal City

In Christianity, the Golden Age of innocence and plenitude represented by the Garden of Eden is balanced by the expectation of an apocalypse followed by the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth, taking the symbolic form of the City of God, “New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven.”11Revelation 21:2, The Bible, King James Version. The New Jerusalem has the features of an ancient city—a great and high wall, many gates, and strong foundations—but it also incorporates the elements of a garden: “And he shewed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal … In the midst of the street of it, and on either side of the river, was there the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits … and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.”12Revelation 22:1-2, The Bible, King James Version. This is Eden, complete with the tree of life and a river, transposed into a city setting, where, in contrast with the original garden, there shall be no more sorrow or pain. In this garden-city, “the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people and God himself shall be with them, and be their God.”13Revelation 21:23, The Bible, King James Version.

Parallel to the messianic vision of Christianity, we find a long tradition of utopian thinking in the West. Broadly speaking, the quest for utopia is the quest for a better society and “has always implied a faith in progress.”14Peter Ruppert, Reader in a Strange Land: The Activity of Reading literary Utopias (Athens, GA : University of Georgia Press, 1986), p. 99 Although the historical events of the last century have made it hard to sustain such a faith, utopian thinking and utopian literature—as well as experiments in utopian living—continue to flourish even today. In many cases, they are quite far from the popular notion that equates utopianism with naïve escapism at best or oppressive totalitarianism at worst. Rather, they are often agents of change that appeal to people to embrace dynamism and diversity as necessary elements of social progress and the attainment of an ideal society.

The classic example of a literary utopia, the one that has given the genre its name, is Thomas More’s Utopia, a description of an imaginary island that enjoys perfection in laws, politics, and economy. More’s work and that of many subsequent writers within the genre are not only “descriptions of a future utopian world” but are also “frequently seen as guides to action.”15Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 120. A feature of More’s utopia is the balance between urban and rural life. The island has “fifty-four spacious and noble cities,” as well as farmsteads throughout the countryside, where “each citizen in his turn must reside.”16Thomas More, Utopia and Other Writings, ed. James J. Greene and John P. Dolan (New York: New American Library, 1984), p. 54.

Furthermore, cities such as the capital, Amaurot, combine typically urban elements such as walls, towers, fortifications, streets designed for carriage travel, and buildings of several stories, with extensive gardens:

Behind the houses are spacious gardens, and each house has a door to the garden as well as one to the street. … The Utopians place great value on their gardens in which they grow fruits, herbs, and flowers. These gardens are extremely well arranged and I have never seen anything more suitable for the pleasure of the citizens.17Thomas More, Utopia and Other Writings, ed. James J. Greene and John P. Dolan (New York: New American Library, 1984), p. 56.

The placement of natural landscapes within an urban setting, once again merging the garden and the city, is a feature of many subsequent utopian worlds, including William Morris’s News from Nowhere and Aldous Huxley’s Island, to name but two.

Utopian thought has also had an influence at the practical level, on city planning. For many modem city planners, as for many utopian visionaries, the ideal city is one in which the urban structure fits a given ideological system based on “assumptions about human nature, equality, happiness, fulfilment and work.”18Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 127.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many thinkers, including philosophers, social reformers, and city planners, were concerned by overcrowding in cities, rural depopulation, the depression of agriculture, and people’s alienation from the land, and they recommended that as many as possible should regain their contact with the land.19Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 122. One plan for achieving this closer contact was the Garden-City Movement initiated in Britain by Ebenezer Howard. His plan for a garden-city consisted of “a series of concentric circles with six boulevards radiating from the centre … In [the] city centre, situated in a park, lay the civic buildings, with residential, shopping, commercial and industrial areas located in different parts of the city … The outermost circle was an agricultural belt which would supply the city with food.”20Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 120. Howard’s aim was to create an alternative to the duality of town and country, one which combined positive aspects of each—the beauty of the country and the activity of urban centers.21Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of Tomorrow (London: Faber, 1945

Although the utopian vision of the garden-city seemed gradually to degenerate into a series of mere town planning techniques, the concept of the ideal city as a symbol of an environment conducive to creating a healthy and happy society has remained. Leon Krier suggests that architecture is about creating “patterns that support communal life in a spiritual and ecologically healthy way.”22Leon Krier, quoted in Leo R. Zrudlo, “The Missing Dimension in the Built Environment: A Challenge for the 21st Century,” Journal of Bahá’i Studies 3, no. l (1990- 91), p. 56. To take it a step further, architecture, in the words of Antonio Sant’Elia, is an “effort … to make the material world a direct projection of the spiritual world.”23Antonio Sant’Elia. “Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto 1914,” in From Futurism to Rationalism—The Origins of Modern Italian Architecture 51, nos. 1/2 (1981), p. 21.

The architectural structures that make up a city can be a means of reflecting spiritual virtues onto the physical world, thereby spiritualizing the social structures that flourish in the material world. As suggested by the examples above, one of the most significant ways in which spiritual qualities can be expressed is by making gardens and natural landscapes part of the architecture of a city and, in some cases, even making the city into a garden. Bahá’u’lláh, Who was Himself deeply fond of nature and the beauty of gardens, is quoted as saying that “the country is the world of the soul, the city is the world of bodies.”24Bahá’u’lláh, quoted in JE Esslemont, Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era, 1950 ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1980), p. 35. Creating beautiful gardens in a city is like bringing soul to the body of that city.

The terraces and gardens surrounding the Shrine of the Báb perform this function. Their architect, Fariborz Sahba, believes that “art is an expression of the outpourings of the Holy Spirit,”25Fariborz Sahba, “Art and Architecture: A Bahá’i Perspective,” Journal of Bahá’i Studies 7, no. 3 ( 1997), p. 54. and he and his colleagues set out to make these gardens the material projections of the spiritual as they reflect such qualities as the love of God, beauty, illumination, and unity in diversity. These are qualities that are destined, through the influence of the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, to transform the hearts of the peoples of the earth. At the same time, they find their physical and visual manifestation on Mount Carmel and, ultimately, in the environment of the entire planet.

The Mystic Encounter with God

The most notable feature of the terraces is that they lead the eye to the Báb’s Shrine, which, no matter the vantage point on the terraces, never ceases to be the dominant center of the mountain. Mr. Sahba compares the design of the terraces to the setting for a precious gem, like a golden ring for a valuable diamond. He says, “If a diamond is not set properly, its value does not show. The Terraces provide both the physical and spiritual setting for the Shrine.”26Fariborz Sahba, quoted in “Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), p. 11. The nineteen terraces—one on the same level as the Shrine of the Báb, nine above it, and nine below—”form a grand series of brackets, which accentuate the Shrine’s position in the heart of the mountainside.”27The nineteen terraces—one on the same level as the Shrine of the Báb, nine above it, and nine below—”form a grand series of brackets, which accentuate the Shrine’s position in the heart of the mountainside.” An aerial view reveals them to be designed as nine concentric circles with the Shrine at their center.

Symbolically, too, they center on the Báb, representing Him and the Letters of the Living, His first eighteen followers. On the ninth terrace, just below the Shrine itself, stand two orange trees, propagated from the seeds taken from an orange tree in the courtyard of the Báb’s house in Shiraz, Iran, before it was destroyed during the Islamic Revolution. In the Shrine, one is reminded of the Báb’s sacrifice and martyrdom; these young trees are reminders of His early life and of the declaration of His mission in the house of His youth. By thus focusing the pilgrims’ and the visitors’ attention on the Báb, the terraces reflect the attitude that the Bahá’í Faith seeks to create in the hearts of people, namely that their thoughts should center on God, as He is revealed through His Messengers, and that their lives should be dedicated to the glorification of their Lord.

In the Bahá’í writings, gardens are sometimes used as metaphors for divine revelation and the Manifestations of God referred to as divine Gardeners. Bahá’u’lláh writes, for example, “Magnified, O Lord my God, be Thy Name, whereby the trees of the garden of Thy Revelation have been clad with verdure, and been made to yield the fruits of holiness.”28Bahá’u’lláh, Prayers and Meditations by Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987), pp. 160- 61. Available at https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/prayers-meditations/4#755895043 Gardens have, throughout the history of the Bahá’í Faith, been associated with the proclamation of God’s new revelation and the beginning of a new dispensation. The three gardens at Badasht, where a conference of the followers of the Báb was held in 1848, witnessed the abrogation of the law of Islam and the proclamation of the advent of a new order.

The Garden of Riḍván in Baghdad was the site of Bahá’u’lláh’s open declaration of His station as the Promised One of past religions and the Manifestation of God for this age. Gardens have often been the site of mystic encounters with God and thus symbolic of the purpose of human life, which is to know and worship God. What better place, then, to tum one’s heart and mind towards God than in a garden?

Spiritual attributes are as much part of the material world as they are of the human. In His Tablet of Wisdom, Bahá’u’lláh writes, “Nature in its essence is the embodiment of My Name, the Maker, the Creator. Its manifestations are diversified by varying causes, and in this diversity there are signs for men of discernment.”29Bahá’u’llah, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1997), p. 142. If we learn to see the Creator in nature, then we come to see our physical environment in a new light. The change that has taken place in Western culture’s dominant metaphors reflects, though indirectly and unconsciously, the influence of the Bahá’í revelation. The last three centuries have witnessed a gradual movement in the West towards an organic view of the world, in which reality is seen to be fluid, dynamic, and composed of “mutually interacting systems.30N Katherine Hayles, The Cosmic Web: Scientific Models and Literary Strategies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984), p. 47 This organic worldview finds expression in the Bahá’í writings. Shoghi Effendi writes, “Man is organic with the world. His inner life moulds the environment and is itself also deeply affected by it.”31Conservation of the Earth’s Resources, comp. Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (London : Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1990), p. iii.

The gardens on Mount Carmel illustrate this nexus between human beings and the natural world and symbolize the harmony that is possible between them when humanity’s actions are spiritually directed and based on an awareness of the divine presence in nature. If the reverence and awe that one experiences in these gardens are reflected in an attitude of respect for all of creation, the physical environment of the planet will indeed be transformed.

The Beauty of Diversity

One of the qualities of the Bahá’í gardens that creates this sense of awe and wonder is their beauty. Beauty is one of the attributes of God, and in the Bahá’í view the impulse to create beauty and the inclination to be drawn to it are signs of human nobility. The beauty of the Bahá’í gardens derives to a great extent from the harmony between different elements and styles, what ‘Abdu’l-Bahá calls “the beauty in diversity, the beauty in harmony.”32‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks: Addresses given by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Paris in 1911-1912 (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1995), p. 52.

The terraces embody this principle of unity in diversity in every detail. The central axis is a formal garden. The stairs leading up to the Shrine of the Báb and thence to the crest of the mountain, together with the fountains, flowerbeds, and paths immediately surrounding them, are symmetrical in design and convey an impression of geometric order. As one moves outwards, however, the landscaping becomes increasingly varied and irregular until it merges into the mountain’s natural environment. The paths are winding; wildflowers, bushes, and trees grow in profusion; and the impression is one of naturalness and spontaneity. Both the man-made and the natural, the formal and the informal, have their place here. Within each terrace, too, one finds a union of divergent elements. The steps are made of stone, but along their sides run streams of water whose murmur gives life to the stone. And while the overall design of the terraces is harmonious, no two levels are exactly the same. Each garden has a unique design, including a color scheme of its own, and is yet integrated into the whole.

Such harmony between different entities is a perfect symbol of the unity in diversity that is the goal of the Bahá’í Faith. In the World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, people, lands, and cultures will preserve their unique characteristics while harmonizing together to form a whole greater and more beautiful than the sum of its parts. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s explanation of the unity of humankind uses the metaphor of a garden:

Diversity of hues, form, and shape enricheth and adorneth the garden, and heighteneth the effect thereof. In like manner, when divers shades of thought, temperament and character are brought together under the power and influence of one agency, the beauty and glory of human perfection will be revealed and made manifest.33‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1997), pp. 291-92.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s powerful metaphor has implications for the physical environment of the planet as well. If the garden is a symbol of a harmonious, joyous, and spiritual mode of living, then what would it mean to transform the whole world into a garden?

Respect for Nature

In his classic utopian novel, News from Nowhere, nineteenth-century English author William Morris writes that his country “was once a country of clearings amongst the woods and wastes… It then became a country of huge and foul workshops … It is now a garden, where nothing is wasted and nothing is spoilt.”34William Morris, News from Nowhere, ed. James Redmond (London: Routledge, 1970), p. 61. A garden is clearly an antithesis to the mechanized, polluted urban wasteland that many fear the world is becoming. But it is also at variance with a primitive and undeveloped wilderness where technology is rejected and progress denied. A garden is a place of living, growing things, where science and art are used to cultivate nature while at the same time serving human needs, both physical and spiritual. The gardens and terraces on Mount Carmel fulfill these purposes. Their existence is the result not only of an inspired artistic sensibility but also of a high order of technological advancement that has allowed a rocky mountainside to be transformed into a verdant and productive garden.

Martin Palmer, secretary-general of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation, describes the terraces as a “fascinating model of bringing order out of chaos.35Martin Palmer, quoted in “Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), p. l2. However, every aspect of the mountain’s transformation is marked by close attention to the ecology of the area and respect for nature ‘s diversity. The plants are chosen not only for their beauty but also for their suitability to the environment. For example, the informal sections of the terraces feature wildflowers that blossom in the fall and winter, and flowering trees and perennial bushes that assume prominence in the spring and summer, while the outer areas have been left free to develop into natural forests that serve as wildlife corridors for a variety of native animals, birds, and insects. The plants contribute to improving the city’s environment by providing a high degree of air filtration and by giving sanctuary to beneficial insects and birds, which in tum provide natural pest control and reduce the need for pesticides. Although the gardens are designed to bloom throughout the year, the choice of appropriate plants together with a judicious combination of ancient and modem gardening practices (such as mulching and composting, computerized irrigation systems, and water recycling) minimize land erosion and place a high priority on water conservation.

Mount Carmel was known to the ancient Hebrews as a symbol of fruitfulness and prosperity. Following a long period of deforestation, during which it turned into a dry, rocky landscape, it has regained its former verdure and beauty. Once again it embodies its Hebrew name “kerem-el,” meaning “vineyard of the Lord.” The harmonious patterns created in the terraces bring pleasure to the senses and peace to the soul, and help create an environment conducive to prayer and meditation.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá says that “it is natural for the heart and spirit to take pleasure and enjoyment in all things that show forth symmetry, harmony, and perfection.”36Bahá’í Writings on Music, comp. Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (Oakham, United Kingdom: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1973), p. 8. The gardens channel this sense of pleasure into the worship and service of God. At the same time, they demonstrate the role that responsible stewardship must play in the conservation of the planet’s resources. As mentioned above, they provide a model for the use of appropriate technology to maintain biodiversity and water and soil conservation. On a symbolic level, they point out the importance of fulfilling universal and basic human needs: the orange trees are sources of nourishment, the fountains provide clean running water, the ornamental seats along the terraces provide shelter and rest. Here, then, is a perfect balance between the preservation of nature and the development of its resources for human use. For the world at large to reflect the qualities displayed by the terraces, its people must learn to achieve harmony between the development and cultivation of land and the natural diversity of the environment, between “agriculture and the preservation of the ecological balance of the world.”37Conservation of the Earth’s Resources, comp. Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (London : Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1990), p. 13.

A Spiritually Charged Landscape

Beyond their function as a model for the transformation of the earth into a harmonious and healthy environment, the gardens on Mount Carmel and the Shrine they embosom constitute the spiritual center, not only of the Bahá’í Faith, but of the whole world. Thomas Beeby, writing about urban form, notes that the ancient Greek cities “grew around their raised holy place” and were “constructed in a spiritually charged landscape.”38Thomas Beeby, “The Cultural Implications of Urban Form: 1984” Cross-Currents of American Architecture 55, nos. l /2 ( 1985), p. 86. From the Bahá’í point of view, a world transformed by the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh will circle around the Shrine of the Báb, a holy place that spiritually charges not only its immediate surroundings, but the entire landscape of the globe. The nine concentric circles radiating from the Shrine were designed to symbolize the entire planet as it is described in the following mighty statement, written by Shoghi Effendi in a letter dated 29 March 1951:

For just as in the realm of the spirit, the reality of the Báb has been hailed by the Author of the Bahá’í Revelation as “The Point round Whom the realities of the Prophets and Messengers revolve,” so, on this visible plane, His sacred remains constitute the heart and center of what may be regarded as nine concentric circles … The outermost circle in this vast system … is none other than the entire planet. Within the heart of this planet lies the “Most Holy Land,” … the center of the world and Qiblih of the nations. Within this Most Holy Land rises the Mountain of God of immemorial sanctity, the Vineyard of the Lord. … Reposing on the breast of this holy mountain are the extensive properties permanently dedicated to, and constituting the sacred precincts of, the Báb’s holy Sepulcher. In the midst of these properties … is situated the most holy court, an enclosure comprising gardens and terraces which at once embellish, and lend a peculiar charm to, these sacred precincts. Embosomed in these lovely and verdant surroundings stands in all its exquisite beauty the mausoleum of the Báb. … Within this shell is enshrined that Pearl of Great Price, the holy of holies, those chambers which constitute the tomb itself … Within the heart of this holy of holies is the tabernacle, the vault wherein reposes the most holy casket. Within this vault rests the alabaster sarcophagus in which is deposited that inestimable jewel, the Báb’s holy dust.39Shoghi Effendi, Citadel of Faith: Messages to America 1947- 1957 (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1995), pp. 95- 96.

The Shrine of the Báb truly resembles a jewel when it is illumined at night. When the hundreds of lights placed throughout the terraces are lit, they outline the shape of the terraces and form a halo above the dome of the Shrine. They seem to trace the rays of the light shining from the Shrine and illuminate the mountain as a whole. The symbolism is deliberate: this brilliant illumination is in sharp contrast with the conditions in which the Báb was imprisoned in the remote fortress of Máh-Kú in northern Iran, where, according to His own testimony, “there [was] not at night even a lighted lamp.”40The Báb, Selections from the Writings of the Báb (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1983), p. 87. Available at www.bahai.org/r/994612588 The dark prison has been symbolically transformed into a luminous garden from which the Sun of Truth, shining forth in the person of the Báb, sheds the light of guidance on those who accept and follow Him.

A Model for Development

These gardens not only exert a spiritual influence on those who visit them, they also have a practical influence on their surroundings. The effect on the city of Haifa is already visible. At the foot of the terraces, the German Templer Colony, built in the nineteenth century by millennialists expecting the return of the Messiah, is being restored and developed, from Haifa’s port to the first terrace’s entrance plaza. As part of the restoration, the municipality has moved Ben Gurion Avenue 1.86 meters to bring it into alignment with the terraces’ central staircase. Alongside the construction of the Bahá’í gardens, efforts have been made throughout Haifa to beautify and develop the city’s streets, parks, beaches, and other areas. At the upper entrance to the terraces, Panorama Drive, which commands an impressive view, has been renovated and further beautified by the construction of the Louis Promenade on its other side. From this spot, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision that “A person standing on the summit of Mount Carmel … will look upon the most sublime and majestic spectacle of the whole world”41‘Abdu’l-Bahá, quoted in Star of the West 24, no. 10 (January 1934), p. 307. is indeed realized. Further afield, the gardens in Haifa provide a model for reexamining horticultural practices in gardens of Bahá’í Houses of Worship around the world to see how they might further conserve water, be weaned from the use of chemical pesticides, and minimize the use of chemical fertilizers. Finally, one may hope that the gardens will encourage individuals and communities to consider ways of beautifying their own physical environments, including both homes and public properties.

The terraces are part of a complex of gardens that surrounds the Bahá’í holy places in Haifa and Acre. The Shrine of the Báb and the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh at Bahjí, near Acre, which is the holiest spot on earth for Bahá’ís, constitute the spiritual center of the Bahá’í Faith. On Mount Carmel, four administrative buildings form an arc near the Shrine of the Báb. These buildings, the Seat of the Universal House of Justice, the International Archives building, the International Teaching Centre building, and the Centre for the Study of the Texts, house the institutions that constitute the world administrative center of the Bahá’í community.

According to their architect, Hossein Amanat, these structures, built in the classic Greek style, create the effect of pavilions adorning the gardens surrounding them.42“Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), p. 14. Here, the atmosphere of peace, harmony, and contemplation that characterizes both the gardens and the buildings helps redefine the concept of religious “administration” as something grounded in a spiritual relationship with God. Shoghi Effendi wrote that the “vast and irresistible process” associated with the work on the Arc, including the surrounding gardens, “will synchronize with two no less significant developments—the establishment of the Lesser Peace and the evolution of Bahá’í national and local institutions.”43Shoghi Effendi, Messages to the Bahá’í World, 1950- 1957 (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1995), p. 74.

Bahá’ís believe that beyond the practical example they provide, the symbolism they offer, and the influence they exert on individuals, the Mount Carmel projects are destined to have effects on the world at large that are as yet indiscernible and unimaginable. Altogether, the Bahá’í gardens offer

a glimpse of the type of world that the Bahá’ís are working for: one that expresses in its harmonious blend of architectural and horticultural styles the principle of unity in diversity, emphasizes in its beauty the precedence of spiritual values over materialism, and, in its open invitation to all, embraces all peoples and cultures.44“Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), pp. 9-10.

As the vital importance of these principles is gradually recognized and they are put into practice in all the different spheres of human life, an unprecedented transformation will indeed occur both within the hearts of the world’s peoples and the physical environment of the planet. Then will the world fulfill its ancient promise and its destiny, as described by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: “The Lord of all mankind hath fashioned this human realm to be a Garden of Eden, an earthly paradise.”45‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1997), p. 275. Available at www.Bahái.org/r/245652735

Whether Bahá’í or non-Bahá’í, Haifa makes pilgrims of all who visit her. The place itself makes mystics of us all—for it shuts out the world of materiality with its own characteristic atmosphere and one instantly feels one’s self in a simple and restful cloistral calm. But it is not the characteristic calm of the monastic cloister—it is not so much a shutting out of the world as an opening up of new vistas—I cannot describe it except to say that its influence lacks the mustiness of ascetism, and blends the joy and naturalness of a nature-cult with the ethical seriousness and purpose of a spiritual religion.

Every thing seems to share the custody of the message—the place itself is a physical revelation. I shall never forget my first view of it from the terraces of the shrine. Mount Carmel, already casting shadows, was like a dark green curtain behind us and opposite was a gorgeous crescent of hills so glowing with color—gold, sapphire, amethyst as the sunset colors changed—and in between the mottled emerald of the sea, and the gray-toned house-roofs of Haifa. Almost immediately opposite and picking up the sun’s reflection like polished metal were the ramparts, of Akká, transformed for a few moments from its shabby decay into a citadel of light and beauty. Most shrines concentrate the view upon themselves—this one turns itself into a panorama of inspiring loveliness. It is a fine symbol for a faith that wishes to reconcile the supernatural with the natural, beauty and joy with morality. It is an ideal place for the reconciliation of things that have been artificially and wrongfully put asunder.

The shrine chambers of the Báb and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá are both impressive, but in a unique and almost modern way: richly carpeted, but with austerely undecorated walls and ceilings, and flooded with light, the ante-chambers are simply the means of taking away the melancholy and gruesomeness of death and substituting for them the thought of memory, responsibility and reverence . Through the curtained doorways, the tomb chambers brilliantly lighted create an illusion which defeats even the realization that one is in the presence of a sepulchre. Here without mysticism and supernaturalness, there is dramatically evoked that lesson of the Easter visitation of the tomb, the fine meaning of which Christianity has in such large measure forgotten—”He is not here, He is risen.” That is to say, one is strangely convinced that the death of the greatest teachers is the release of their spirit in the world, and the responsible legacy of their example bequeathed to posterity. Moral ideas find their immortality through the death of their founders.

It was a privilege to see and experience these things. But it was still more of a privilege to stand there with the Guardian of the Cause, and to feel that, accessible and inspiring as it was to all who can come and will come, there was available there for him a constant source of inspiration and vision from which to draw in the accomplishment of his heavy burdens and responsibilities. That thought of communion with ideas and ideals without the mediation of symbols seemed to me the most reassuring and novel feature. For after all the only enlightened symbol of a religious or moral principle is the figure of a personality endowed to perfection with its qualities and necessary attributes. Earnestly renewing this inheritance seemed the constant concern of this gifted personality, and the quiet but insistent lesson of his temperament.

Refreshingly human after this intense experience, was the relaxation of our walk and talk in the gardens. Here the evidences of love, devotion and service were as concrete and as practical and as human as inside the shrines they had been mystical and abstract and super-human. Shogi Effendi is a master of detail as well as of principle, of executive foresight as well as of projective vision. But I have never heard details so redeemed of their natural triviality as when talking to him of the plans for the beautifying and laying out of the terraces and gardens. They were important because they all were meant to dramatize the emotion of the place and quicken the soul even through the senses. It was night in the quick twilight of the east before we had finished the details of inspecting the gardens, and then by the lantern light, the faithful gardener showed us to the austere retreat of the great Expounder of the teaching. It taught me with what purely simple and meager elements a master workman works. It is after all in himself that he finds his message and it is himself that he gives with it to the world.

The household is an industrious beehive of the great work: splendid division of labor but with all-pervading unity of heart. Never have I seen the necessary subordinations of organized service so full of a sense of dignity and essential equality as here. I thought that in the spirit of such devoted co-operation and cheerful self-subordination there was the potential solution of those great problems of class and caste which today so affect society. Labor is dignified through the consciousness of its place and worth to the social scheme, and no Bahá’í worker, however humble, seems unconscious of the dignity and meaning of the whole plan.

Then there was the visit to the Bahjí, the garden spot of the Faith itself and to Akká, now a triumphant prison-shell that to me gave quite the impression one gets from the burst cocoon of the butterfly. Vivid as the realization of cruelty and hardships might be, there was always the triumphant realization here that opposite on the heights of Carmel was enshrined the victory that had survived and conquered and now was irrepressible. The Bahjí was truly oriental, as characteristically so as Mt. Carmel had been cosmopolitan. Here was the eastern vision, full of its mysticism, its poetry, its spirituality. Not only was sombreness lacking, but even seriousness seemed converted into poetry. Surely the cure for the ills of western materialism is here, waiting some more psychological moment for its spread—for its destined mission of uniting in a common mood western and oriental minds.

There is a new light in the world: there must needs come a new day.