A moving meditation penned by the Báb during His imprisonment in Máh-Kú, in the mountains of Azerbaijan, praises God for having turned a prison fortress into a noble chamber and an oppressive mountain into a heavenly garden. It reads:

How can I praise Thee, O Lord, for the evidences of Thy mighty splendor and for Thy wondrous sweet savors which Thou hast imparted to Me in this fortress … Thou hast watched over Me in the heart of this mountain where I am compassed by mountains on all sides. One hangeth above Me, others stand on My right and My left and yet another riseth in front of Me … Having suffered Me to be cast into the prison, Thou didst tum it into a garden of Paradise for Me and caused it to become a chamber of the court of everlasting fellowship.1The Báb, Selections from the Writings of the Báb (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1983), pp. 183- 84. Available at www.bahai.org/r/864833549

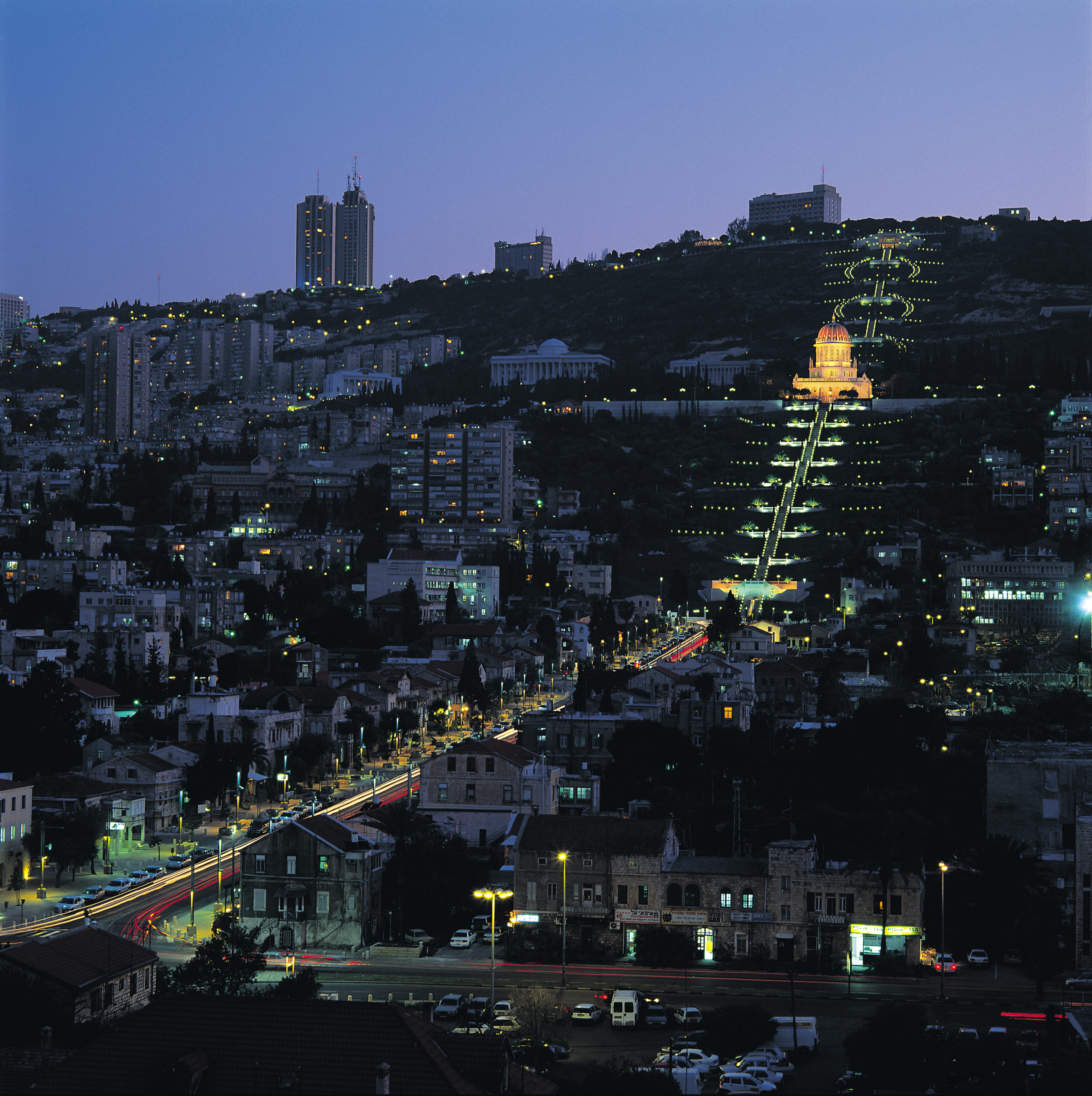

The terraces surrounding the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel in Haifa, which are nearing completion, are a powerful reminder of this transformation and thus a fitting means of paying tribute to the Báb and for enhancing the beauty of the resting place of His earthly remains. But in addition to effecting the transformation of a once barren and rocky mountain into a verdant, blooming garden, the nineteen terraces also symbolize another kind of change. In the words of the Universal House of Justice in a letter regarding the significance of these monumental edifices, “The beauty and magnificence of the Gardens and Terraces … are symbolic of the nature of the transformation which is destined to occur both within the hearts of the world’s people and in the physical environment of the planet.”2Letter of the Universal House of Justice to all National Spiritual Assemblies, 4 January 1994. Available at www.bahai.org/r/283913957

Visions of Paradise

The terraced gardens on Mount Carmel conjure up, for many of those who walk through them, images of the Garden of Eden, of paradise as it is described in various religious traditions. In Biblical Eden, “out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. And a river went out of Eden to water the garden.”3Genesis 2:9- 10, The Bible, King James Version. In the Qur’an, it is promised that in paradise, “the righteous shall drink of a cup tempered at the Camphor Fountain, a gushing spring at which the servants of God will refresh themselves … Reclining there upon soft couches, they shall feel neither the scorching heat nor the biting cold. Trees will spread their shade around them, and fruits will hang in clusters over them.”4Qur’an 76:8- 9, trans. N.J. Dawood. The influence of this vision of paradise is evident in traditional Persian gardens, which had “one central unifying purpose: praise of the Divine.”5Julie Scott Meisami, “Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (1985), p. 242. In fact, the word paradise itself “derives from the old Persian word pairidaeza … which meant the royal park, enclosure, or orchard of the Persian king.”6Julie Scott Meisami, “Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (1985), p. 231.

running water. . . and a pool to reflect the beauties of sky and garden; trees of various sorts, some to provide shade merely, and others to produce fruits; flowers, colorful and sweet-smelling; grass, usually growing wild under the trees; birds to fill the garden with song; the whole cooled by a pleasant breeze. The garden might include a raised hillock at the centre … often surmounted by a pavilion or palace.7Julie Scott Meisami, “Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 17, no. 2 (1985), p. 231.

This could almost serve as a description of the gardens on Mount Carmel. Here one’s eyes are indeed delighted by the sight of every kind of tree and flower, and one’s ears soothed by the murmur of running water and the song of birds. And at the center, more majestic than any palace, stands the golden-domed Shrine of the Báb, dedicated to the praise of God. As in Eden, where Adam and Eve “heard the voice of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day,”8Genesis 3:8, The Bible, King James Version many feel that this, too, is a place where God can be found. The terraces are, indeed, as Howard Adelman has described them, “the approach to a sacred place.”9Howard Adelman, narrating, “Bahá’í Hanging Gardens.” Television program, first broadcast on Israel Today, Canada, 6 December 1999.

However, as Louis Greenspan points out in a perceptive commentary on the locales of religious expression, in the Bible the garden is never an unmixed blessing. Eden is the archetypal garden for which humanity longs, but it is also the place of temptation, fall, and expulsion. The hanging gardens of Babylon—literally, “the Gate of God”- were considered to be one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, but they are associated on the one hand with sensual pleasure and on the other with the labor of slaves, among them captive and exiled Jews. Another Biblical garden, Gethsemane, is the scene of Christ’s agony and His betrayal. “The garden by itself is not paradise; the city is also needed with its energy,” says Greenspan.10Louis Greenspan on “Bahá’í Hanging Gardens.” Television program, first broadcast on Israel Today, Canada, 6 December 1999. And indeed, the ideal city is a parallel and related theme in religious traditions as well as in secular visions of the world. It finds expression in disciplines as different as religious millennialism, utopian literature, and urban planning.

The Ideal City

In Christianity, the Golden Age of innocence and plenitude represented by the Garden of Eden is balanced by the expectation of an apocalypse followed by the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth, taking the symbolic form of the City of God, “New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven.”11Revelation 21:2, The Bible, King James Version. The New Jerusalem has the features of an ancient city—a great and high wall, many gates, and strong foundations—but it also incorporates the elements of a garden: “And he shewed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal … In the midst of the street of it, and on either side of the river, was there the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits … and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.”12Revelation 22:1-2, The Bible, King James Version. This is Eden, complete with the tree of life and a river, transposed into a city setting, where, in contrast with the original garden, there shall be no more sorrow or pain. In this garden-city, “the tabernacle of God is with men, and he will dwell with them, and they shall be his people and God himself shall be with them, and be their God.”13Revelation 21:23, The Bible, King James Version.

Parallel to the messianic vision of Christianity, we find a long tradition of utopian thinking in the West. Broadly speaking, the quest for utopia is the quest for a better society and “has always implied a faith in progress.”14Peter Ruppert, Reader in a Strange Land: The Activity of Reading literary Utopias (Athens, GA : University of Georgia Press, 1986), p. 99 Although the historical events of the last century have made it hard to sustain such a faith, utopian thinking and utopian literature—as well as experiments in utopian living—continue to flourish even today. In many cases, they are quite far from the popular notion that equates utopianism with naïve escapism at best or oppressive totalitarianism at worst. Rather, they are often agents of change that appeal to people to embrace dynamism and diversity as necessary elements of social progress and the attainment of an ideal society.

The classic example of a literary utopia, the one that has given the genre its name, is Thomas More’s Utopia, a description of an imaginary island that enjoys perfection in laws, politics, and economy. More’s work and that of many subsequent writers within the genre are not only “descriptions of a future utopian world” but are also “frequently seen as guides to action.”15Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 120. A feature of More’s utopia is the balance between urban and rural life. The island has “fifty-four spacious and noble cities,” as well as farmsteads throughout the countryside, where “each citizen in his turn must reside.”16Thomas More, Utopia and Other Writings, ed. James J. Greene and John P. Dolan (New York: New American Library, 1984), p. 54.

Furthermore, cities such as the capital, Amaurot, combine typically urban elements such as walls, towers, fortifications, streets designed for carriage travel, and buildings of several stories, with extensive gardens:

Behind the houses are spacious gardens, and each house has a door to the garden as well as one to the street. … The Utopians place great value on their gardens in which they grow fruits, herbs, and flowers. These gardens are extremely well arranged and I have never seen anything more suitable for the pleasure of the citizens.17Thomas More, Utopia and Other Writings, ed. James J. Greene and John P. Dolan (New York: New American Library, 1984), p. 56.

The placement of natural landscapes within an urban setting, once again merging the garden and the city, is a feature of many subsequent utopian worlds, including William Morris’s News from Nowhere and Aldous Huxley’s Island, to name but two.

Utopian thought has also had an influence at the practical level, on city planning. For many modem city planners, as for many utopian visionaries, the ideal city is one in which the urban structure fits a given ideological system based on “assumptions about human nature, equality, happiness, fulfilment and work.”18Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 127.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many thinkers, including philosophers, social reformers, and city planners, were concerned by overcrowding in cities, rural depopulation, the depression of agriculture, and people’s alienation from the land, and they recommended that as many as possible should regain their contact with the land.19Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 122. One plan for achieving this closer contact was the Garden-City Movement initiated in Britain by Ebenezer Howard. His plan for a garden-city consisted of “a series of concentric circles with six boulevards radiating from the centre … In [the] city centre, situated in a park, lay the civic buildings, with residential, shopping, commercial and industrial areas located in different parts of the city … The outermost circle was an agricultural belt which would supply the city with food.”20Ian Tod and Michael Wheeler, Utopia (London: Orbis, 1978), p. 120. Howard’s aim was to create an alternative to the duality of town and country, one which combined positive aspects of each—the beauty of the country and the activity of urban centers.21Ebenezer Howard, Garden Cities of Tomorrow (London: Faber, 1945

Although the utopian vision of the garden-city seemed gradually to degenerate into a series of mere town planning techniques, the concept of the ideal city as a symbol of an environment conducive to creating a healthy and happy society has remained. Leon Krier suggests that architecture is about creating “patterns that support communal life in a spiritual and ecologically healthy way.”22Leon Krier, quoted in Leo R. Zrudlo, “The Missing Dimension in the Built Environment: A Challenge for the 21st Century,” Journal of Bahá’i Studies 3, no. l (1990- 91), p. 56. To take it a step further, architecture, in the words of Antonio Sant’Elia, is an “effort … to make the material world a direct projection of the spiritual world.”23Antonio Sant’Elia. “Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto 1914,” in From Futurism to Rationalism—The Origins of Modern Italian Architecture 51, nos. 1/2 (1981), p. 21.

The architectural structures that make up a city can be a means of reflecting spiritual virtues onto the physical world, thereby spiritualizing the social structures that flourish in the material world. As suggested by the examples above, one of the most significant ways in which spiritual qualities can be expressed is by making gardens and natural landscapes part of the architecture of a city and, in some cases, even making the city into a garden. Bahá’u’lláh, Who was Himself deeply fond of nature and the beauty of gardens, is quoted as saying that “the country is the world of the soul, the city is the world of bodies.”24Bahá’u’lláh, quoted in JE Esslemont, Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era, 1950 ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1980), p. 35. Creating beautiful gardens in a city is like bringing soul to the body of that city.

The terraces and gardens surrounding the Shrine of the Báb perform this function. Their architect, Fariborz Sahba, believes that “art is an expression of the outpourings of the Holy Spirit,”25Fariborz Sahba, “Art and Architecture: A Bahá’i Perspective,” Journal of Bahá’i Studies 7, no. 3 ( 1997), p. 54. and he and his colleagues set out to make these gardens the material projections of the spiritual as they reflect such qualities as the love of God, beauty, illumination, and unity in diversity. These are qualities that are destined, through the influence of the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, to transform the hearts of the peoples of the earth. At the same time, they find their physical and visual manifestation on Mount Carmel and, ultimately, in the environment of the entire planet.

The Mystic Encounter with God

The most notable feature of the terraces is that they lead the eye to the Báb’s Shrine, which, no matter the vantage point on the terraces, never ceases to be the dominant center of the mountain. Mr. Sahba compares the design of the terraces to the setting for a precious gem, like a golden ring for a valuable diamond. He says, “If a diamond is not set properly, its value does not show. The Terraces provide both the physical and spiritual setting for the Shrine.”26Fariborz Sahba, quoted in “Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), p. 11. The nineteen terraces—one on the same level as the Shrine of the Báb, nine above it, and nine below—”form a grand series of brackets, which accentuate the Shrine’s position in the heart of the mountainside.”27The nineteen terraces—one on the same level as the Shrine of the Báb, nine above it, and nine below—”form a grand series of brackets, which accentuate the Shrine’s position in the heart of the mountainside.” An aerial view reveals them to be designed as nine concentric circles with the Shrine at their center.

Symbolically, too, they center on the Báb, representing Him and the Letters of the Living, His first eighteen followers. On the ninth terrace, just below the Shrine itself, stand two orange trees, propagated from the seeds taken from an orange tree in the courtyard of the Báb’s house in Shiraz, Iran, before it was destroyed during the Islamic Revolution. In the Shrine, one is reminded of the Báb’s sacrifice and martyrdom; these young trees are reminders of His early life and of the declaration of His mission in the house of His youth. By thus focusing the pilgrims’ and the visitors’ attention on the Báb, the terraces reflect the attitude that the Bahá’í Faith seeks to create in the hearts of people, namely that their thoughts should center on God, as He is revealed through His Messengers, and that their lives should be dedicated to the glorification of their Lord.

In the Bahá’í writings, gardens are sometimes used as metaphors for divine revelation and the Manifestations of God referred to as divine Gardeners. Bahá’u’lláh writes, for example, “Magnified, O Lord my God, be Thy Name, whereby the trees of the garden of Thy Revelation have been clad with verdure, and been made to yield the fruits of holiness.”28Bahá’u’lláh, Prayers and Meditations by Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987), pp. 160- 61. Available at https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/bahaullah/prayers-meditations/4#755895043 Gardens have, throughout the history of the Bahá’í Faith, been associated with the proclamation of God’s new revelation and the beginning of a new dispensation. The three gardens at Badasht, where a conference of the followers of the Báb was held in 1848, witnessed the abrogation of the law of Islam and the proclamation of the advent of a new order.

The Garden of Riḍván in Baghdad was the site of Bahá’u’lláh’s open declaration of His station as the Promised One of past religions and the Manifestation of God for this age. Gardens have often been the site of mystic encounters with God and thus symbolic of the purpose of human life, which is to know and worship God. What better place, then, to tum one’s heart and mind towards God than in a garden?

Spiritual attributes are as much part of the material world as they are of the human. In His Tablet of Wisdom, Bahá’u’lláh writes, “Nature in its essence is the embodiment of My Name, the Maker, the Creator. Its manifestations are diversified by varying causes, and in this diversity there are signs for men of discernment.”29Bahá’u’llah, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1997), p. 142. If we learn to see the Creator in nature, then we come to see our physical environment in a new light. The change that has taken place in Western culture’s dominant metaphors reflects, though indirectly and unconsciously, the influence of the Bahá’í revelation. The last three centuries have witnessed a gradual movement in the West towards an organic view of the world, in which reality is seen to be fluid, dynamic, and composed of “mutually interacting systems.30N Katherine Hayles, The Cosmic Web: Scientific Models and Literary Strategies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984), p. 47 This organic worldview finds expression in the Bahá’í writings. Shoghi Effendi writes, “Man is organic with the world. His inner life moulds the environment and is itself also deeply affected by it.”31Conservation of the Earth’s Resources, comp. Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (London : Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1990), p. iii.

The gardens on Mount Carmel illustrate this nexus between human beings and the natural world and symbolize the harmony that is possible between them when humanity’s actions are spiritually directed and based on an awareness of the divine presence in nature. If the reverence and awe that one experiences in these gardens are reflected in an attitude of respect for all of creation, the physical environment of the planet will indeed be transformed.

The Beauty of Diversity

One of the qualities of the Bahá’í gardens that creates this sense of awe and wonder is their beauty. Beauty is one of the attributes of God, and in the Bahá’í view the impulse to create beauty and the inclination to be drawn to it are signs of human nobility. The beauty of the Bahá’í gardens derives to a great extent from the harmony between different elements and styles, what ‘Abdu’l-Bahá calls “the beauty in diversity, the beauty in harmony.”32‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks: Addresses given by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Paris in 1911-1912 (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1995), p. 52.

The terraces embody this principle of unity in diversity in every detail. The central axis is a formal garden. The stairs leading up to the Shrine of the Báb and thence to the crest of the mountain, together with the fountains, flowerbeds, and paths immediately surrounding them, are symmetrical in design and convey an impression of geometric order. As one moves outwards, however, the landscaping becomes increasingly varied and irregular until it merges into the mountain’s natural environment. The paths are winding; wildflowers, bushes, and trees grow in profusion; and the impression is one of naturalness and spontaneity. Both the man-made and the natural, the formal and the informal, have their place here. Within each terrace, too, one finds a union of divergent elements. The steps are made of stone, but along their sides run streams of water whose murmur gives life to the stone. And while the overall design of the terraces is harmonious, no two levels are exactly the same. Each garden has a unique design, including a color scheme of its own, and is yet integrated into the whole.

Such harmony between different entities is a perfect symbol of the unity in diversity that is the goal of the Bahá’í Faith. In the World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, people, lands, and cultures will preserve their unique characteristics while harmonizing together to form a whole greater and more beautiful than the sum of its parts. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s explanation of the unity of humankind uses the metaphor of a garden:

Diversity of hues, form, and shape enricheth and adorneth the garden, and heighteneth the effect thereof. In like manner, when divers shades of thought, temperament and character are brought together under the power and influence of one agency, the beauty and glory of human perfection will be revealed and made manifest.33‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1997), pp. 291-92.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s powerful metaphor has implications for the physical environment of the planet as well. If the garden is a symbol of a harmonious, joyous, and spiritual mode of living, then what would it mean to transform the whole world into a garden?

Respect for Nature

In his classic utopian novel, News from Nowhere, nineteenth-century English author William Morris writes that his country “was once a country of clearings amongst the woods and wastes… It then became a country of huge and foul workshops … It is now a garden, where nothing is wasted and nothing is spoilt.”34William Morris, News from Nowhere, ed. James Redmond (London: Routledge, 1970), p. 61. A garden is clearly an antithesis to the mechanized, polluted urban wasteland that many fear the world is becoming. But it is also at variance with a primitive and undeveloped wilderness where technology is rejected and progress denied. A garden is a place of living, growing things, where science and art are used to cultivate nature while at the same time serving human needs, both physical and spiritual. The gardens and terraces on Mount Carmel fulfill these purposes. Their existence is the result not only of an inspired artistic sensibility but also of a high order of technological advancement that has allowed a rocky mountainside to be transformed into a verdant and productive garden.

Martin Palmer, secretary-general of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation, describes the terraces as a “fascinating model of bringing order out of chaos.35Martin Palmer, quoted in “Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), p. l2. However, every aspect of the mountain’s transformation is marked by close attention to the ecology of the area and respect for nature ‘s diversity. The plants are chosen not only for their beauty but also for their suitability to the environment. For example, the informal sections of the terraces feature wildflowers that blossom in the fall and winter, and flowering trees and perennial bushes that assume prominence in the spring and summer, while the outer areas have been left free to develop into natural forests that serve as wildlife corridors for a variety of native animals, birds, and insects. The plants contribute to improving the city’s environment by providing a high degree of air filtration and by giving sanctuary to beneficial insects and birds, which in tum provide natural pest control and reduce the need for pesticides. Although the gardens are designed to bloom throughout the year, the choice of appropriate plants together with a judicious combination of ancient and modem gardening practices (such as mulching and composting, computerized irrigation systems, and water recycling) minimize land erosion and place a high priority on water conservation.

Mount Carmel was known to the ancient Hebrews as a symbol of fruitfulness and prosperity. Following a long period of deforestation, during which it turned into a dry, rocky landscape, it has regained its former verdure and beauty. Once again it embodies its Hebrew name “kerem-el,” meaning “vineyard of the Lord.” The harmonious patterns created in the terraces bring pleasure to the senses and peace to the soul, and help create an environment conducive to prayer and meditation.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá says that “it is natural for the heart and spirit to take pleasure and enjoyment in all things that show forth symmetry, harmony, and perfection.”36Bahá’í Writings on Music, comp. Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (Oakham, United Kingdom: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1973), p. 8. The gardens channel this sense of pleasure into the worship and service of God. At the same time, they demonstrate the role that responsible stewardship must play in the conservation of the planet’s resources. As mentioned above, they provide a model for the use of appropriate technology to maintain biodiversity and water and soil conservation. On a symbolic level, they point out the importance of fulfilling universal and basic human needs: the orange trees are sources of nourishment, the fountains provide clean running water, the ornamental seats along the terraces provide shelter and rest. Here, then, is a perfect balance between the preservation of nature and the development of its resources for human use. For the world at large to reflect the qualities displayed by the terraces, its people must learn to achieve harmony between the development and cultivation of land and the natural diversity of the environment, between “agriculture and the preservation of the ecological balance of the world.”37Conservation of the Earth’s Resources, comp. Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (London : Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1990), p. 13.

A Spiritually Charged Landscape

Beyond their function as a model for the transformation of the earth into a harmonious and healthy environment, the gardens on Mount Carmel and the Shrine they embosom constitute the spiritual center, not only of the Bahá’í Faith, but of the whole world. Thomas Beeby, writing about urban form, notes that the ancient Greek cities “grew around their raised holy place” and were “constructed in a spiritually charged landscape.”38Thomas Beeby, “The Cultural Implications of Urban Form: 1984” Cross-Currents of American Architecture 55, nos. l /2 ( 1985), p. 86. From the Bahá’í point of view, a world transformed by the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh will circle around the Shrine of the Báb, a holy place that spiritually charges not only its immediate surroundings, but the entire landscape of the globe. The nine concentric circles radiating from the Shrine were designed to symbolize the entire planet as it is described in the following mighty statement, written by Shoghi Effendi in a letter dated 29 March 1951:

For just as in the realm of the spirit, the reality of the Báb has been hailed by the Author of the Bahá’í Revelation as “The Point round Whom the realities of the Prophets and Messengers revolve,” so, on this visible plane, His sacred remains constitute the heart and center of what may be regarded as nine concentric circles … The outermost circle in this vast system … is none other than the entire planet. Within the heart of this planet lies the “Most Holy Land,” … the center of the world and Qiblih of the nations. Within this Most Holy Land rises the Mountain of God of immemorial sanctity, the Vineyard of the Lord. … Reposing on the breast of this holy mountain are the extensive properties permanently dedicated to, and constituting the sacred precincts of, the Báb’s holy Sepulcher. In the midst of these properties … is situated the most holy court, an enclosure comprising gardens and terraces which at once embellish, and lend a peculiar charm to, these sacred precincts. Embosomed in these lovely and verdant surroundings stands in all its exquisite beauty the mausoleum of the Báb. … Within this shell is enshrined that Pearl of Great Price, the holy of holies, those chambers which constitute the tomb itself … Within the heart of this holy of holies is the tabernacle, the vault wherein reposes the most holy casket. Within this vault rests the alabaster sarcophagus in which is deposited that inestimable jewel, the Báb’s holy dust.39Shoghi Effendi, Citadel of Faith: Messages to America 1947- 1957 (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1995), pp. 95- 96.

The Shrine of the Báb truly resembles a jewel when it is illumined at night. When the hundreds of lights placed throughout the terraces are lit, they outline the shape of the terraces and form a halo above the dome of the Shrine. They seem to trace the rays of the light shining from the Shrine and illuminate the mountain as a whole. The symbolism is deliberate: this brilliant illumination is in sharp contrast with the conditions in which the Báb was imprisoned in the remote fortress of Máh-Kú in northern Iran, where, according to His own testimony, “there [was] not at night even a lighted lamp.”40The Báb, Selections from the Writings of the Báb (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1983), p. 87. Available at www.bahai.org/r/994612588 The dark prison has been symbolically transformed into a luminous garden from which the Sun of Truth, shining forth in the person of the Báb, sheds the light of guidance on those who accept and follow Him.

A Model for Development

These gardens not only exert a spiritual influence on those who visit them, they also have a practical influence on their surroundings. The effect on the city of Haifa is already visible. At the foot of the terraces, the German Templer Colony, built in the nineteenth century by millennialists expecting the return of the Messiah, is being restored and developed, from Haifa’s port to the first terrace’s entrance plaza. As part of the restoration, the municipality has moved Ben Gurion Avenue 1.86 meters to bring it into alignment with the terraces’ central staircase. Alongside the construction of the Bahá’í gardens, efforts have been made throughout Haifa to beautify and develop the city’s streets, parks, beaches, and other areas. At the upper entrance to the terraces, Panorama Drive, which commands an impressive view, has been renovated and further beautified by the construction of the Louis Promenade on its other side. From this spot, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision that “A person standing on the summit of Mount Carmel … will look upon the most sublime and majestic spectacle of the whole world”41‘Abdu’l-Bahá, quoted in Star of the West 24, no. 10 (January 1934), p. 307. is indeed realized. Further afield, the gardens in Haifa provide a model for reexamining horticultural practices in gardens of Bahá’í Houses of Worship around the world to see how they might further conserve water, be weaned from the use of chemical pesticides, and minimize the use of chemical fertilizers. Finally, one may hope that the gardens will encourage individuals and communities to consider ways of beautifying their own physical environments, including both homes and public properties.

The terraces are part of a complex of gardens that surrounds the Bahá’í holy places in Haifa and Acre. The Shrine of the Báb and the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh at Bahjí, near Acre, which is the holiest spot on earth for Bahá’ís, constitute the spiritual center of the Bahá’í Faith. On Mount Carmel, four administrative buildings form an arc near the Shrine of the Báb. These buildings, the Seat of the Universal House of Justice, the International Archives building, the International Teaching Centre building, and the Centre for the Study of the Texts, house the institutions that constitute the world administrative center of the Bahá’í community.

According to their architect, Hossein Amanat, these structures, built in the classic Greek style, create the effect of pavilions adorning the gardens surrounding them.42“Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), p. 14. Here, the atmosphere of peace, harmony, and contemplation that characterizes both the gardens and the buildings helps redefine the concept of religious “administration” as something grounded in a spiritual relationship with God. Shoghi Effendi wrote that the “vast and irresistible process” associated with the work on the Arc, including the surrounding gardens, “will synchronize with two no less significant developments—the establishment of the Lesser Peace and the evolution of Bahá’í national and local institutions.”43Shoghi Effendi, Messages to the Bahá’í World, 1950- 1957 (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1995), p. 74.

Bahá’ís believe that beyond the practical example they provide, the symbolism they offer, and the influence they exert on individuals, the Mount Carmel projects are destined to have effects on the world at large that are as yet indiscernible and unimaginable. Altogether, the Bahá’í gardens offer

a glimpse of the type of world that the Bahá’ís are working for: one that expresses in its harmonious blend of architectural and horticultural styles the principle of unity in diversity, emphasizes in its beauty the precedence of spiritual values over materialism, and, in its open invitation to all, embraces all peoples and cultures.44“Reshaping ‘God’s holy mountain’ to create a vision of peace and beauty for all humanity.” One Country 12, no. 2 (July-Septembcr 2000), pp. 9-10.

As the vital importance of these principles is gradually recognized and they are put into practice in all the different spheres of human life, an unprecedented transformation will indeed occur both within the hearts of the world’s peoples and the physical environment of the planet. Then will the world fulfill its ancient promise and its destiny, as described by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: “The Lord of all mankind hath fashioned this human realm to be a Garden of Eden, an earthly paradise.”45‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette: Bahá’i Publishing Trust, 1997), p. 275. Available at www.Bahái.org/r/245652735

Not the least of the treasures which Bahá’u’lláh has given to the world is the wealth of His prayers and meditations. He not only revealed them for specific purposes, such as the Daily Prayers, the prayers for Healing, for the Fast, for the Dead, and so on, but in them He revealed a great deal of Himself to us. At moments it is as if, in some verse or line, we are admitted into His Own heart, with all its turbulent emotions, or catch a glimpse of the workings of a mind as great and deep as an ocean, which we can never fathom, but which never ceases to enrapture and astonish us.

If one could be so presumptuous as to try and comment on a subject so vast and which, ultimately, is far beyond the capacity of any merely mortal mind to analyse or classify, one might say that one of His masterpieces is the long prayer for the Nineteen Day Fast. I do not know if He revealed it at dawn, but He had, evidently, a deep association with that hour of the day when the life of the world is repoured into it. How could He not have? Was He not the Hermit of Sar-Galú, where He spent many months in a lonely stone hut perched on a hilltop; the sunrise must have often found Him waiting and watching for its coming, His voice rising and falling in the melodious chants of His supplications and compositions. At how many dawns He must have heard the birds of the wilderness wake and cry out when the first rays of the sun flowed over the horizon and witnessed in all its splendor the coming alive of creation after the night.

In this prayer it is as if the worshipper approaches the sun while the sun is approaching its daybreak. When one remembers that the sun, the lifegiver of the earth, has ever been associated with the God Power, and that Bahá’u’lláh has always used it in His metaphors to symbolize the Prophet, the prayer takes on a mystical significance that delights and inspires the soul. Turning to the budding day He opens His supplication:

“I beseech Thee, O my God, by Thy mighty Sign (the Prophet), and by the revelation of Thy grace amongst men, to cast me not away from the gate of the city of Thy presence, and to disappoint not the hopes I have set on the manifestations of Thy grace amidst Thy creatures.” Who has not, in order to better visualize himself in relation to the Kingdom of God, seen his own soul as a wanderer, weary and hopeful, standing at the Gates of the Heavenly City and longing for admittance? The worshipper gazes at the brightening sky in the east and waits, expectant of the mercy of God. He hears the “most sweet Voice” and supplicates that by the “most exalted Word” he may draw ever nearer the threshold of God’s door and enter under the shadow of the canopy of His bounty—a canopy which is already spreading itself, in mighty symbolic form, over the world in crimson, gold, and gray clouds.

The day waxes; the oncoming sun, in the prayer of Bahá’u’lláh, becomes the face of God Himself to which He turns, addressing words of infinite sweetness and yearning: “I beseech Thee, O my God, by the splendor of Thy luminous brow and the brightness of the light of Thy countenance, which shineth from the all-highest horizon, to attract me, by the fragrance of Thy raiment, and make me drink of the choice wine of Thine utterance.”

The soft winds of dawn, which must have often played over His face and stirred His black locks against His cheek, may have given rise to this beautiful phrase in His prayer: “I beseech Thee, O my God, by Thy hair which moveth across Thy face, even as Thy most exalted pen moveth across the pages of Thy tablets, shedding the musk of hidden meanings over the kingdom of Thy creation, so to raise me up to serve Thy Cause that I shall not fall back, nor be hindered by the suggestions of them who have cavilled at Thy signs and turned away from Thy face.” How deep, how poetical, how sincere are His words! The playing of the strands of hair recall to Him the fine tracing of the Persian script, revealing words from God that shed a divine fragrance in the lives of men. But that is not all. In His communion all the love and loyalty of His heart is roused, He supplicates to be made of the faithful, whom naught shall turn aside from the Path that leads them to their Lord.

The sun has risen, as if in answer to the cry of the worshipper to “enable me to gaze on the Day-Star of Thy Beauty. …” And as he continues his prayer it seems as if all nature were moving in harmony with it: “I beseech Thee, O my God, by the Tabernacle of Thy majesty on the loftiest summits, and the Canopy of Thy Revelations on the highest hills, to graciously aid me to do what Thy will hath desired and Thy purpose hath manifested.” North and south the glory spreads, a faint echo of that celestial beauty visible to the eye of Baha’u’llah and which He says: “shineth forth above the horizon of eternity.” So deeply does it penetrate the heart that it evokes the desire to “die to all that I possess and live to whatsoever belongeth unto Thee,” The soul is moved; all earthly things pale before the vision which, as symbolized in the sunrise, it beholds in the inner world; God, the “Well-beloved” seems to have drawn very near.

The winds flit over the land; some tree calls to the Prophet’s mind, as it shivers and stirs, the Tree of Himself that over-shadows all mankind: “I beseech Thee, O my God, by the rustling of the Divine Lote-Tree and the murmur of the breezes of Thine utterance in the kingdom of Thy names, to remove me far from whatsoever Thy will abhorreth, and draw me nigh unto the station wherein He who is the Day-Spring of Thy signs hath shone forth.” Bahá’u’lláh puts the words into our mouths whereby we may draw nigher to God and receive from Him the heavenly gifts: “I beseech Thee … to make known unto me what lay hid in the treasuries of Thy knowledge and concealed within the repositories of Thy wisdom.” “I beseech Thee … to number me with such as have attained unto that which Thou hast sent down in Thy Book and manifested through Thy will.” “I beseech Thee … to write down for me what Thou hast written down for Thy trusted ones. …”

And finally, in words designed for those countless worshippers for whom He wrote this glorious Fasting Prayer, He asks God to “ write down for every one who hath turned unto Thee, and observed the fast prescribed by Thee, the recompense decreed for such as speak not except by Thy leave, and who forsook all chat they possessed in Thy path and for love of Thee.” He asks that the silence of the good may descend upon them-both the silence and the speech of chose who are wholly dedicated to that Divine Will which alone can lead men to their highest destiny. The last thought of all is that those who have obeyed the decrees of God may be forgiven their trespasses.

This majestic prayer is composed of fourteen verses, each opening with the words “I beseech Thee …” and closing with the same refrain: “Thou seest me, O my God, holding to Thy Name, the Most Holy, the Most Luminous, the Most Mighty, the Most Great, the Most Exalted, the Most Glorious, and clinging to the hem of the robe to which have clung all in this world and in the world to come.” The rhythmical emphasis on the thoughts contained in these words is not only very powerful but very artistic—if one may borrow the term for lack of a better one–and the sense that all creatures living, and chose gone before into the invisible realms of God, are clinging to the skirt of His mercy, dependent on Him and Him alone, exerts a profound influence on one’s mind, particularly so when taken in conjunction with what one beholds at this hour of the day: The sky kindling with light, the brush of the wind gently over the face of nature; the whole world waking to the casks of living on all sides; all things dependent on God; they always have and they always will be. This is a little of what this long prayer conveys to the those who partake of it.

Another unique prayer of Bahá’u’lláh is His congregation prayer for the Dead. His Revelation throughout has aimed at doing away with every form of ritual; He has abolished priesthood; forbidden ceremonials, in the sense of church services with a set form; reduced the conduct of marriages to a naked simplicity, with a minimum uniform rite required of those concerned. The one exception to this general policy is the Prayer for the Dead, portions of which are repeated while all present are standing. Prayers such as this and the one for the Fast, can never be properly appreciated by merely reading them. They are living experiences. The difference is as great as looking at a brook while you are not thirsty, and drinking from it when you are. If you lose some one you love and then read aloud the glorious words, you come to know what “living waters” are:

“This is Thy servant … deal with him, O Thou Who forgivest the sins of men and concealest their faults, as beseemeth the heaven of Thy bounty and the ocean of Thy grace. Grant him admission within the precincts of Thy transcendent mercy that was before the foundation of earth and heaven. …” Simple words, words which follow our loved one out into the spaces where we may not follow. But the profound experience of this prayer is in the refrain, each sentence of which is repeated 19 times. “We all, verily, worship God. We all, verily, bow down before God. We all, verily, are devoted unto God. We all, verily, give praise unto God. We all, verily, yield thanks unto God. We all, verily, are patient in God.”

The very strength of the prayer is in the repetition. It is so easy to say just once, “We … bow down before God” or “We yield thanks unto God” or “We are patient in God”; the words slip off our minds swiftly and leave them much as before. But when we say these things over and over, they sink very deep, they go down into the puzzled, the rebellious, the grief stricken or numbly resigned heart and stir it with healing powers; reveal to it the wisdom of God’s decrees, seal it with patience in His ways,—ways which run the stars in their courses smoothly and carry us on to our highest good.

No form of literature in the whole world is less objective than prayers. They are things of motion, not of repose. They are speeches addressed to a Hearer; they are medicine applied to a wound; they stir the worshipper and set something in his heart at work. That is their whole purpose. Teachings, discourses, even meditations, can be read purely objectively and critically, but the man who can read a real prayer in the cold light of reason alone, has indeed strayed far from his own innate human nature, for all men, everywhere, at every period in their evolution, have possessed the instinct of supplication, the necessity of calling out to something, some One, greater than themselves, whether in their abasement it was a stone image, thunder or fire, or, in their glory, the invisible God of all men that they called upon, the instinct was there just as deeply.

Many wonderful prayers exist in all languages and all religions; but the prayers of Bahá’u’lláh possess a peculiar power and richness all their own. He calls upon God in terms of the greatest majesty, of the deepest feeling; sometimes with awe; sometimes with pathos; sometimes in a voice of such exultation that we can only wonder what transpired within his soul at such moments. He uses figures of speech that strike the imagination, stir up new concepts of the Divinity and expand infinitely our spiritual horizons. Much, no doubt, of their perfection is lost in translation as He often employed the possibilities and peculiarities of the Arabic and Persian languages to their fullest. Some of His prayers, following the style of the Súrihs of the Qur’án, end every sentence in rhyme—though they are not poems—and the custom of alliterating words, thus imparting a flowing sense of rhythm to the sentences, is very often resorted to in all His writings, including His prayers. Nevertheless the original charm and beauty pervades the translations and none of the lyric quality of the following prayer seems to have been lost. It rises like a beautiful hymn which lifts the soul on wings of song:

“From the sweet-scented streams of Thine eternity give me to drink, O my God, and of the fruits of the tree of Thy being enable me to taste, O my Hope! From the crystal springs of Thy love suffer me to quaff, O my Glory, and beneath the shadow of Thine everlasting providence let me abide, O my Light! Within the meadows of Thy nearness, before Thy presence, make me able to roam, O my Beloved, and at the right hand of the throne of Thy mercy, seat me, O my Desire! From the fragrant breezes of Thy joy let a breath pass over me, O my Goal, and into the heights of the paradise of Thy reality let me gain admission, O my Adored One! To the melodies of the dove of Thy oneness suffer me to hearken, O Resplendent One, and through the spirit of Thy power and Thy might quicken me, O my Provider! In the spirit of Thy love keep me steadfast, O my Succorer, and in the path of Thy good pleasure set firm my steps, O my Maker! Within the garden of Thine immortality, before Thy countenance, let me abide for ever, O Thou Who art merciful unto me, and upon the seat of Thy glory stablish me, O Thou Who art my Possessor! To the heaven of Thy loving-kindness lift me up, O my Quickener, and unto the Daystar of Thy guidance lead me, O Thou my Attractor! Before the revelations of Thine invisible spirit summon me to be present, O Thou Who art my Origin and my Highest Wish, and unto the essence of the fragrance of Thy beauty, which Thou wilt manifest, cause me to return, O Thou Who art my God!

“Potent art Thou to do what pleaseth Thee. Thou art, verily, the Most Exalted, the All-Glorious, the All-Highest.”

At times Bahá’u’lláh put words into the mouth of the worshipper according to his need: He writes a supplication for a child, for one who is ill, one who is sad, one who is pregnant, one who is a sinner, one who pours forth his heart to God—capturing the whole gamut of human emotions in His various communions. But at times it is obvious the prayer is His own. We read it, but we cannot be the speaker, or mortal feet cannot tread the path that lay between His soul—the soul of the Prophet Himself—and the God Who sent Him here among men to labor and suffer for them. “I know not,” He declares, “what the water is with which Thou hast created me, or what the fire Thou hast kindled within me, or the clay wherewith Thou hast kneaded me. The restlessness of every ocean hath been stilled, but not the restlessness of this Ocean which moveth at the bidding of the words of Thy will. The flame of every fire hath been extinguished, except the Flame which the hands of Thine omnipotence have kindled, and whose radiance Thou hast, by the power of Thy name, shed abroad before all that are in Thy heaven and that are on Thy earth. As the tribulations deepen, it waxeth hotter and hotter.” The Holy fire that burned within His being is not for us, frail creatures that we are, to comprehend. We can only gaze into its heart and marvel at its shifting hues and beauty, much as we marvel at the flames that leap and dance on our own hearth fires, though we may not approach or touch them.

Bahá’u’lláh exalts the being and nature of God, in His addresses to Him, as no other Prophet ever has. He defines His relation to Him; He gives us glimpses of the forces surging within His soul; He lay bare the emotions that stir within His turbulent breast. In words of honey He cries out: “Thou beholdest, O my God, how every bone in my body soundeth like a pipe with the music of Thine inspiration. …” A love far beyond our ken burns in His heart for the One God who sent Him down amongst men: “Thou seest, O Thou Who art my All-Glorious Beloved, the restless waves that surge within the ocean of my heart in my love for Thee. …” “Thou art, verily, the Lord of Bahá and the Beloved of his heart, and the Object of his desire, and the Inspirer of his tongue, and the Source of his Soul.” “Lauded be Thy name, O Thou Who art my God and throbbest within my heart!” “O would that they who serve Thee could taste what I have tasted of the sweetness of Thy love!” How keenly His soul thrilled with appreciation for the aid that poured into His inmost being from the Invisible Source: “Were I to render thanks unto Thee for the whole continuance of Thy kingdom and the duration of the heaven of Thine omnipotence, I would still have failed to repay Thy manifold bestowals.” How ardent is His gratitude to His Lord for raising Him up to serve His fellowmen: “How can I thank Thee for having singled me out and chosen me above all Thy servants to reveal Thee, at a time when all have turned away from Thy beauty!”

Ever and again He confesses His readiness, nay, His eagerness, to bear every trial and hardship for the sake of shedding the light of God upon this darkened world, and in order to demonstrate the greatness of the love He feels for His Creator: “I yield Thee thanks for that Thou hast made me the target of diverse tribulations and manifold trials in order that Thy servants may be endued with new life and all Thy creatures may be quickened.” “I yield Thee thanks, O my God, for that Thou hast offered me up as a sacrifice in Thy path … and singled me out for all manner of tribulation for the regeneration of Thy people.” “I swear by Thy glory! I have accepted to be tried by manifold adversities for no purpose except to regenerate all that are in Thy heaven and on Thy earth.” “How sweet is the thought of Thee in times of adversity and trial, and how delightful to glorify Thee when compassed about by the fierce winds of Thy decree.” “Every hair of my head proclaimeth: ‘But for the adversities that befall me in Thy path how could I ever taste the divine sweetness of Thy tenderness and love?’”

With what passion and majesty He testifies to the unquenchable power and purpose of His Lord—the Lord Whom He called His “Fire” and His “Light”—which burned within His breast: “Were all that are in the heavens and all that are on the earth to unite and seek to hinder me from remembering Thee and from celebrating Thy praise, they would assuredly … fail … And were all the infidels to slay me, my blood would … lift up its voice and proclaim: ‘There is no God but Thee, O Thou Who Art all my heart’s desire!’ And were my flesh to be boiled in the cauldron of hate, the smell which it would send forth would rise towards Thee and cry out: ‘Where art Thou, O Lord of the Worlds, the One Desire of them that have known Thee!’ And were I to be cast into fire, my ashes would—I swear by Thy glory—declare: ‘The Youth hath, verily, attained that for which he had besought His Lord the All-Glorious, the Omniscient.’”

Reading such testimonials that sprang in moments of who knows what exaltation?—from the heart of the prophet, we cannot but marvel at the mighty and strange bond that binds such a Being to the Source of all power. It is as if an invisible umbilical cord tied Him to His Creator; all His life, His motivations, His inspiration, His very words, flowed down this divine channel, as all the life, blood, and food of the babe flows in through that one bond it has with its mother. He throbbed in this mortal world with the vibrations of a celestial world; He set all things pulsating with Him, whether they knew it or not, and drew them up and closer to the throne of God. One of His most moving and sublime rhapsodies is included in a meditation in which He testifies to the power of the praise which He pours out to God, to transform and influence the hearts of others: “I yield Thee such thanks,” He declares, “as can direct the steps of the wayward towards the splendors of the morning light of Thy guidance. … I yield Thee such thanks as can cause the sick to draw nigh unto the waters of Thy healing, and can help those who are far from Thee to approach the living fountain of Thy presence …. I yield Thee such thanks as can stir up all things to extol Thee . . . and can unloose the tongues of all beings to … magnify Thy beauty … I yield Thee such thanks as can make the corrupt tree to bring forth good fruit … and revive the bodies of all beings with the gentle winds of Thy transcendent grace. … I yield Thee such thanks as can cause Thee to forgive all sins and trespasses, and to fulfill the needs of the peoples of all religions, and to waft the fragrances of pardon over the entire creation. … I yield Thee such thanks as can satisfy the wants of all such as seek Thee, and realize the aims of them that have recognized Thee. I yield thee such thanks as can blot out from the hearts of men all suggestions of limitation. …”

Poetic and stirring as these words are, we need not assume them to be merely the effusions of an exalted and over-filled heart. Bahá’u’lláh was never idle in His words. If He tells us that enshrined in the thanks He poured forth to His God is a power that can blot out every limitation from the hearts of men, it is so. The trouble is with us. How many Seers and Prophets, how many scientists and pioneers, have brought men tidings of truths and powers they knew not of and offered them to their generation, only to be spat upon, laughed to scorn, killed or ignored? And in the end a more enlightened people would take the key and open the door and find the wonders that the incredulous disbelieved, to be all true, ready at hand, waiting to be used for their good. The Prophets of God are intent on giving us both the good of this world and the one awaiting us after death, but most of the time we will not have it. We, blind and perverse, prefer our own ways! Did not Christ say: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, … how often would I have gathered Thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings, and ye would not!” It is not a new story. Every Divine Manifestation has placed jewels in the hands of man, only to see them flung aside for some foolish toy of his choosing.

Yet each Prophet has assured us that God’s pity knows no bounds. “Thou art, in truth,” states Bahá’u’lláh in one of His prayers, “He Who mercy hath encompassed all the worlds, and Whose grace hath embraced all who dwell on earth and in heaven. Who is there who hath cried after Thee, and whose prayers hath remained unanswered? Where is he to be found who hath reached forth towards Thee, and whom Thou hast failed to approach? Who is he who can claim to have fixed his gaze upon Thee, and towards whom the eye of Thy loving-kindness hath not been directed? I bear witness that Thou hadst turned toward Thy servants ere they had turned toward Thee, and hadst remembered them ere they had remembered Thee.”

It is an education in divinity to read Bahá’u’lláh’s prayers. He maintained the unique nature of God, the utter impossibility of any creature approaching or comprehending Him, in a clear and graphic manner. The unseen God of Moses; the “Father” of Christ, unto Whom none cometh to but through the Son; the One of Whom Muhammad so beautifully said: “Eyes see Him not but He sees the eyes,” is exalted, one might say, to unimaginable heights by Him. “Thou art He Whom all things worship and Who worshipeth no one, Who is the Lord of all things and the vassal of none, Who knoweth all things and is known of none.” “From everlasting Thou hast existed alone with no one beside Thee, and wilt, to everlasting, continue to remain the same, in the sublimity of Thine essence and the inaccessible heights of Thy glory,” He declares. In a short and wonderful prayer He solemnly sets forth the fundamental doctrine of the nature of God with a lucidity and power that would, in any past dispensation, have gained it first place in the dogmas of the church:

“God testifieth to the unity of His Godhood and to the singleness of His Own Being. On the throne of eternity, from the inaccessible heights of His station, His tongue proclaimeth that there is none other God but Him. He Himself, independently of all else, hath ever been a witness unto His own oneness, the revealer of His own nature, the glorifier of His own essence. He, verily, is the All-Powerful, the Almighty, the Beauteous.

“He is supreme over His servants, and standeth over His creatures. In His hand is the source of authority and truth. He maketh men alive by His signs, and causeth them to die through His wrath. He shall not be asked of His doings and His might is equal unto all things. He is the Potent, the All-Subduing. He holdeth within His grasp the empire of all things, and on His right hand is fixed the Kingdom of His Revelation. His power, verily, embraceth the whole of creation. Victory and over-lordship are His; all might and dominion are His; all glory and greatness are His. He, of a truth, is the All-Glorious, the Most Powerful, the Unconditioned.”

The “Unconditioned.” That one word provides ample food for thought. Some of the adjectives Bahá’u’lláh uses for the Godhead are most striking and seem to plow up our minds and prepare them for an infinitely deeper and richer concept of the One on Whom we depend for everything we have, be it physical or spiritual. For instance: “O God Who art the Author of all Manifestations . . . the Fountain-Head of all Revelations, and the Well-Spring of all Lights.” As words are the tools of men’s thoughts, they are tremendously important. The “Well-Spring of all Lights,” though but another way of saying, that all the Prophets are generated by God, presents a tremendous mental picture to a man who has studied something of modern astronomy, of a universe which is light upon light, of matter which itself is the stuff of which light is made. Compare the mental picture this phase conjures up with that of an anthropomorphic God, bearded, stern and much like a human grandfather, who created the world in six days and took a rest on the seventh! Though no doubt when that metaphor was propounded it opened up men’s minds to a new and wider concept of the Divinity. A being Who could do all that in six days was worthy of worship and to be strictly obeyed!

Bahá’u’lláh calls God “the Pitier of thralls,” “the Pitier of the downtrodden,” “the Help in peril,” “the Great Giver,” “the Restorer”—words which sink into our hearts these dark days with an added comfort as we see so many of our fellow-men downtrodden, in deadly danger, despoiled and broken. He tells us that this “King of Kings,” this “Quickener of every mouldering bone,” this “Enlightener of all creation” Who is the “Lord of all mankind” and the “Lord of the Judgment Day” is the One “Whom nothing whatsoever can frustrate.” Such a God will right all wrongs and rule the world for the good of man! Grievous, on the other hand, as are our sins, as testified by these words: “Wert Thou to regard Thy servants according to their deserts … they would assuredly merit naught except Thy chastisement …” He yet assures us, in the words He addresses to God, that: “All the atoms of the earth testify that Thou art the Ever-Forgiving, the Benevolent, the Great Giver …” and that “the whole universe testifieth to Thy generosity.” Even though He be the Lord “Whose strength is immense, Whose decree is terrible,” yet we can confidently turn to Him, and, in Bahá’u’lláh’s words declare: “A drop out of the ocean of Thy mercy sufficeth to quench the flames of hell, and a spark of the fire of Thy love is enough to set ablaze a whole world.”

Our world is steadily sinking into ruin. We have waxed proud and forgotten our God—as many a people has before us to its soul’s undoing—and turned away from Him, disbelieved in Him, followed proudly our own fancies and desires. No Being that was not such a Being as Bahá’u’lláh depicts would still hold open His door to us! And yet in how many passages such as these the way back, the way we once trod but have now, for the most part, forgotten, is pointed out to us and words placed in our mouths that are food for our sick hearts and souls: “Cleanse me with the waters of Thy Mercy, O my Lord, and make me wholly Thine. …” “I am all wretchedness, O my Lord, and Thou art the Most Powerful, the Almighty!” “Thy Might, in truth, is equal to all things!” “Whosoever has recognized Thee will turn to none save Thee, and will seek for naught else except Thyself.” “Help me to guard the pearls of Thy love, which by Thy decree, Thou hast enshrined in my heart.” “‘Many a chilled heart, O my God, hath been set ablaze with the fire of Thy Cause, and many a slumberer hath been awakened by the sweetness of Thy voice.”

Of such stuff as these is the treasury of prayers which Bahá’u’lláh has left us. They are suited to the child before he goes to sleep at night, to the mystic, to the busy man of practical outlook, to the devout. An instance of the comprehension and tolerance with which He viewed human nature is the fact that He revealed a choice of three daily, and obligatory, prayers. While imposing on men the obligation of turning to their Creator once, at least, during every day, He provided a means of doing so suited to widely different natures. One takes about thirty seconds to recite and is to be said at the hour of noon; one is longer and is to be used three times during the day; and the third is very long and profound, accompanied by many genuflexions, and may be used any time during the twenty-four hours of the day. The Divine Physician provided us with what we might call a spiritual polish with which to brighten our hearts. We need this renewal which comes through turning to the Sun of Eternal Truth—as every bird and beast, be it ever so humble, responds to the light of the physical sun at dawn—but he gave latitude to the individual state of development and temperament.

Some Westerners have found the long Daily Prayer very strange; no doubt this is because the present generation has ceased to feel intimate with its God. For a man to stand alone in his room and stretch his arms out to nothingness, or kneel down before a blank wall, in the midst of familiar objects, seems to him unnatural and even foolish. This is because he has lost the sense of the “living God.” God, far from being to him, as the Qur’án says, “nearer than his life’s vein,” has become more of an X in some vast equation. And yet men that we honor and men that we long to emulate have not felt shy before their God. Many a burly crusader knelt on the stones of Jerusalem where he felt His Lord’s feet might have trod, and the Pilgrim Fathers did not feel self-conscious on their knees when turning to God who had led them to a new and freer homeland. The prayers of Bahá’u’lláh will help lead us back to that warm sense of the reality and nearness of God, through use. He makes no compulsion, He takes our hand and guides us into the safe road trodden by our forefathers.

No survey, however cursory and inadequate, of His Prayers would be complete without quoting one of the most passionate and moving of them all, one associated with probably the saddest hours of His whole life. After His banishment from Persia to ‘Iráq the initial signs of envy and hatred began to be apparent from His younger brother, Mírzá Yaḥyá. In order to avoid open rupture and the consequent humiliation of the Faith in the eyes of the non-believers, Bahá’u’lláh retired for two years to the wilderness of Kurdistan and lived, unknown, as a dervish among its people.

During His absence the situation, far from improving, now that the field was left open and uncontested to Mírzá Yaḥyá, steadily deteriorated. Shameful acts took place and conditions became so acute that the believers sent a messenger in search of Baha’u’llah to report to Him and beseech His return. Reluctantly He turned His face towards Baghdad. He was going back to mount the helm; storms lay ahead of Him of a severity and bitterness no other Prophet had ever known; behind Him, once and for all, He left a measure of peace and seclusion. For two years He had communed with His own soul. He had written wonderful poems and revealed beautiful prayers and treatises. Now He headed back into the inky blackness of an implacable hatred and jealousy, where attempts against His very life were to be plotted and even prove partially successful. As He tramped along through the wilderness, beautiful in its dress of spring, the messenger that had gone to fetch Him back testified that He chanted over and over again this prayer. It rolled forth like thunder from His agonized heart:

“O God, my God! Be Thou not far from me, for tribulation upon tribulation hath gathered about me. O God, my God! Leave me not to myself, for the extreme of adversity hath come upon me. Out of the pure milk, drawn from the breasts of Thy loving-kindness, give me to drink, for my thirst hath utterly consumed me. Beneath the shadow of the wings of Thy mercy shelter me, for all mine adversaries with one consent have fallen upon me. Keep me near to the throne of Thy majesty, face to face with the revelations of the signs of Thy glory, for wretchedness hath grievously touched me. With the fruits of the tree of Thine Eternity nourish me, for uttermost weakness hath overtaken me. From the cups of joy, proffered by the hands of Thy tender mercies, feed me, for manifold sorrows have laid mighty hold upon me. With the broidered robe of Thine omnipotent sovereignty attire me, for poverty hath altogether despoiled me. Lulled by the cooing of the Dove of Thine Eternity, suffer me to sleep, for woes at their blackest have befallen me. Before the throne of Thy oneness, amid the blaze of the beauty of Thy countenance, cause me to abide, for fear and trembling have violently crushed me. Beneath the ocean of Thy forgiveness, faced with the restlessness of the leviathan of glory, immerse me, for my sins have utterly doomed me.”