In this article from Volume XV of the Bahá’í World (1968-1973), Adib Taherzadeh looks at the extraordinary period of Revelation immediately after Bahá’u’lláh’s imprisonment in Akká.

At this particular juncture in the history of the Formative Age of the Faith, when the followers of Bahá’u’lláh in most parts of the world have, under the unerring guidance of the Universal House of Justice, embarked upon extensive programmes of proclamation designed to bring the Faith out of obscurity into the notice of the generality of mankind, it is most appropriate that we turn our hearts and souls to the events of a century ago when the King of Kings was issuing the remainder of His majestic summons to the kings and rulers of the world from the prison of ‘Akká.

In the summer of 1868, through the intrigues of the Persian Ambassador in Turkey and the hostility of ‘Álí Páshá, Grand Vizir of the Sultan (of Turkey), Bahá’u’lláh was imprisoned in the barracks of ‘Akká and confined to a small room which looked desolate and depressing. This room, the interior of which today is kept in good condition and is visited by innumerable pilgrims from all the world over, was, in the days of Bahá’u’lláh, uninhabitable and dilapidated. He Himself mentions in a Tablet that its floor was covered with thick dust, and what plaster remained on the ceiling was often falling down.

A number of officials, ill disposed, hateful, and unaccommodating, were commissioned to guard and isolate Him from the outside world. Thus Bahá’u’lláh, the Supreme Manifestation Of God, He at Whose advent “the hearts of the entire company” of God’s “Messengers and Prophets were proved”, “Whose presence” Moses “hath longed to attain”, for “Whose love” the spirit of Jesus “ascended to heaven”, “the beauty of Whose countenance” Muhammad “had yearned to behold”, and “for Whose sake” the Báb had “sacrificed” Himself—the Bearer of such a mighty Revelation, fallen into the hands of a perverse generation, being wronged and afflicted with calamities, was now secluded within the walls of a barracks designated by Him as the “Most Great Prison”.

The Cause He revealed, however, had by then been well established in the land of His birth. His followers after years of misfortune and uncertainty were reinvigorated, their faith strengthened and their souls galvanized.

At the time of Bahá’u’lláh’s arrival in the prison city of ‘Akká, well nigh six years had elapsed since the Most Great Festival had been ushered in through Bahá’u’lláh’s declaration in the Garden of Riḍván, when the whole creation was “immersed in the sea of purification” and the splendours of the light of His countenance broke upon the world.

The Cause of God had by then witnessed a prodigious outpouring of divine Revelation for five years in Adrianople, culminating in the historic proclamation of His Message in that land. The Súriy-i-Mulúk (Súrih of the Kings) had been revealed in a language of authority and power; through it the clarion call of a mighty King had been sounded and His claims fully asserted.

The Tablet described by Him as “the rumbling” of His proclamation, addressed to Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh of Persia, had been revealed though not yet delivered.

His first Tablet to Napoleon III, in which the sincerity of that monarch concerning His statement in defence of the oppressed among the Turks was tested, had been dispatched and received. The Súriy-i-Ra’ís (Arabic), in which ‘Álí Páshá had been severely rebuked, and about which Baha’u’llah had testified that from the moment of its revelation “until the present day, neither hath the world been tranquilized, nor have the hearts of its people been at rest,” had been revealed and the prophecies it contained had been noted with awe and wonder.

Now in ‘Akká, though confined to a cell and cut off from the body of the believers, the outpourings of Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation did not cease. The ocean of His utterance continued to surge, and the “Tongue of Grandeur” spoke with authority and might. The Pen of the Most High directed its warnings and exhortations first to His immediate persecutors and then to some of the more outstanding monarchs of the world at that time.

BAHÁ’U’LLÁH WARNS ‘ÁLÍ PÁSHÁ

Soon after His confinement in the prison barracks in 1868, Bahá’u’lláh addressed another Tablet of tremendous importance to ‘Álí Páshá, who had been an implacable enemy and the prime instigator of His banishment to the prison of ‘Akká, and who previously had been addressed by Him as Ra’ís (i.e. Chief).

In this second Tablet (Persian), known as the Lawḥ-i-Ra’ís, Bahá’u’lláh recounts with much tenderness and resignation the hardships and sufferings to which He and His companions had been subjected on their arrival in ‘Akká; describes very movingly the cruelties perpetrated by the guards in the prison; reminds the Grand Vizir that the Manifestations of God in every age had suffered at the hands of the ungodly; narrates a story for him of His own childhood, portraying in a dramatic way the instability and futility of this earthly life; counsels him not to rely on his pomp and glory as they would come to an end soon; reveals to him the greatness of this Revelation; points out his impotence to quench the fire of the Cause of God; admonishes him for the iniquities he had perpetrated; emphatically warns him that God’s chastisement would assail him from every direction and confusion overtake his peoples and government; and affirms that the wrath of God had so surrounded him that he would never be able to repent or make amends.

On this last point Mírzá Áqá Ján, Bahá’u’lláh’s amanuensis, asked Bahá’u’lláh what would happen if ‘Álí Páshá changed his attitude and truly repented. Bahá’u’lláh’s emphatic response was that whatever had been revealed in the Lawḥ-i-Ra’ís would inevitably be fulfilled, and if the whole world were to join together in order to change one word of that Tablet they would be impotent to do so.

A majestic contrast took place one hundred years later when passages from this very Tablet, depicting the rigours and hardships of the Most Great Prison, were chanted in the vicinity of Bahá’u’lláh’s Most Holy Tomb, in the presence of over two thousand of His followers gathered from every corner of the world to commemorate the centenary of the arrival in ‘Akká of the One Whom the world had wronged.

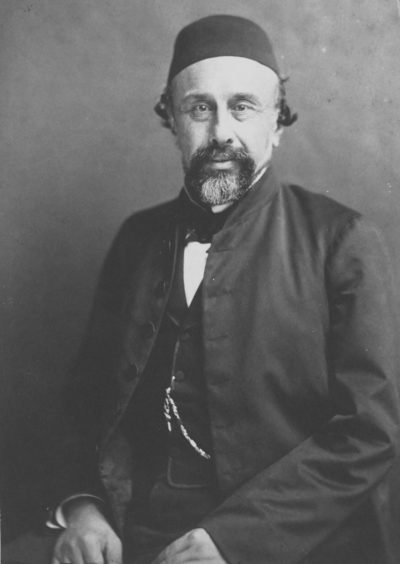

THE TABLET OF FU’ÁD

Another Tablet of great significance, the The Tablet of Fu’ád, was revealed in 1869, soon after the premature death in Nice, France, of Fu’ád Pasha, the foreign minister of the Sultan and a faithful accomplice of the Prime Minister in bringing about the exile of Bahá’u’lláh to ‘Akká. It was revealed in honour of one of Bahá’u’lláh’s most devoted apostles, Shaykh Káẓim-i-Samandar (father of the late Hand of the Cause of God Ṭaráẓu’lláh Samandarí). The following passage from it contains the clear prediction of the downfall of ‘Álí Páshá and the Sultan himself: “Soon will We dismiss the one who was like unto him (i.e. ‘Álí Páshá), and will lay hold on their Chief (i.e. the Sultan) who ruleth the land, and l, verily, am the Almighty, the All-Compelling.” Soon after the revelation of the Tablet, ‘Álí Páshá: was dismissed from his post, and two years later he died.

In those days the believers in Persia often referred to Baha’u’llah’s newly revealed Tablets to the kings and rulers of the world, and many non-Bahá’ís made their acceptance of the Faith conditional upon the fulfilment of the warnings they contained.

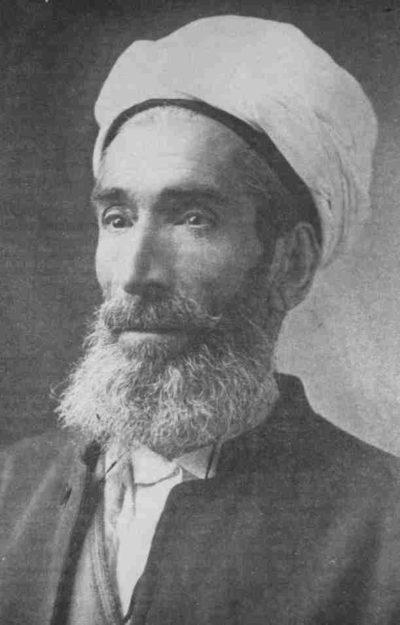

A notable example is the case of Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl, the greatest of Bahá’í scholars. He was renowned for his knowledge and learning among the divines of lslam, and was the head of the Theological College in Tihran. His first contact with the Faith was through meeting a blacksmith who was a Bahá’í at his shop in the outskirts of Tihran. Never before had Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl been so humiliated as on this occasion, when, with all his knowledge, he was utterly confounded by the amazing force of the argument of this illiterate Bahá’í. The blacksmith immediately reported this whole episode to a Bahá’í friend, ‘Abdu’l-Karím, who, although he did not belong to the learned class, pursued Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl and eventually succeeded in bringing him to his house to discuss the Faith.

At this meeting, and subsequent ones, Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl, confronted with some simple Bahá’ís who were not of his calibre, found himself over and over again incapable of refuting the clear proofs and arguments put forward by his uneducated Bahá’í teachers. He marvelled at these men who answered his difficult and abstruse questions so simply and so brilliantly. From there on he visited more often the house of ‘Abdu’l-Karim. He read many of the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh and met many learned Bahá’ís, but his immense knowledge was a barrier and a veil.

One day in 1876 he met Ḥájí Muḥammad Ismá‘íl-i-Káshání, surnamed Anís. Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl was handed the original copy of this Súrih in the very handwriting of Mírzá Áqá Ján, Bahá’u’lláh’s amanuensis; the Tablet wherein Baha’u’llah foretells that Adrianople will pass out of the Sultan’s hand and that confusion will overtake his kingdom. He was also given the Tablet of Fu’ád, in which the downfall of the Sultan is clearly prophesied. Upon seeing these two Tablets Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl made his acceptance of the Faith conditional upon the fulfilment of these prophecies.

His Bahá’í friends pursued him no longer. A few months passed and the news of the assassination of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz reached Tihran. On hearing the news Abu’l-Faḍl became very agitated. His soul was yearning for confirmation of the truth of this Cause, and yet his heart was not touched by the light of faith. He sat the whole night, read some Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, and prayed with absolute sincerity until his eyes were opened and he knew the truth of the Cause of God. At the hour of dawn he went to the house of that faithful friend ‘Abdu’l-Karím, and when the door was opened he kissed the threshold of that house and prostrated himself at the feet of the man who, through perseverance and love, had given him the gift of the Faith and led him to the truth.

It is no exaggeration to say that among the apostles of Baha’u’llah there was no one who surpassed Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl in his knowledge, his humility and self-effacement. Ali-Kuli Khan, a well-known and learned Bahá’í who was commissioned by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to serve Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl in America and act as his interpreter, has described him so well in these few lines: “If I had never seen ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi, I would consider Mírzá Abu’l-Faḍl the greatest being I ever laid eyes on.”

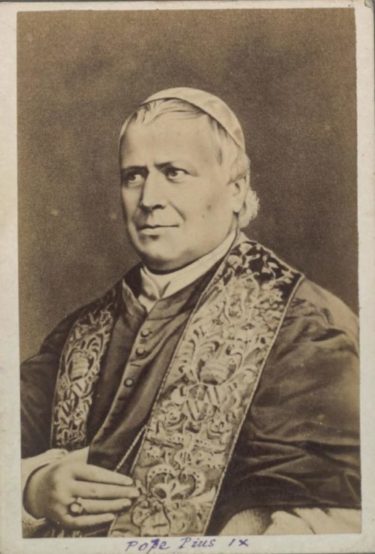

THE DOWNFALL OF A MONARCH AND A POPE

Let us turn our thoughts again to Bahá’u’lláh. Though captive in the hands of His enemies and cut off from the outside world, the Supreme Pen wrote many more Tablets in the prison of ‘Akká. In the year 1869 two important Tablets were revealed and delivered; one addressed to Napoleon III, in which Bahá’u’lláh explicitly foretells his extinction; the other to Pope Pius IX. Within almost a year’s time Napoleon, the most powerful monarch of his time in Europe, was driven into exile and suffered an ignominious death, while in the same year the supreme Pontiff’s temporal powers which had existed for many centuries, were seized from him and his vast dominion was reduced to the tiny Vatican State.

Parallel with these events and indeed, ever since Bahá’u’lláh had been sent to the prison of ‘Akká, the believers in Persia were desperately trying to establish contact with Him. Many travelled on foot all the way, but could not gain admittance to that city. The officials had taken many precautions in order to prevent the Bahá’ís from entering. The few Azalís, headed by the notorious Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání, who is described by the beloved Guardian as the “embodiment of wickedness”, were housed in a certain room overlooking the landgate. One of their functions was to watch for any Bahá’í who might wish to enter the city and to inform the guards. This they did with great zeal and enthusiasm. Many believers, even though they had disguised themselves, were recognized by these men and were not allowed to enter.

Every day a party consisting of a small number of Baha’u’llah’s companions, including ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, was allowed out of the barracks in order to purchase food and other necessities in the markets of ‘Akká. The first time that the people of ‘Akká took notice of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was in a butcher’s shop. While waiting to be served He noticed that a Christian and a Muslim were discussing their faiths, but the Muslim was being defeated. Thereupon, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá simply and eloquently proved the authenticity and truth of Islam for the Christian. The news of this spread and warmed the hearts of many people of ‘Akká towards the Master; this was the beginning of His immense popularity among the inhabitants of that city.

During these daily visits, the people of ‘Akká came in touch with the person of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. They felt His genuine love and compassion and were attracted to His magnetic personality. Gradually their fear and animosity towards Bahá’u’lláh and His followers were removed, and many became sympathetic to the Faith and its Founder. Some of these people who were attracted to the Faith tried, at times to help the believers, who were refused entry, by lowering ropes and pulling the believers up over the walls of the city—attempts which however were foiled by the guards.

The first two believers who managed to get into the city were Ḥájí Sháh Muḥammad and Ḥájí Abu’l-Ḥasan, both from the province of Yazd. The former was the first Trustee of Bahá’u’lláh, and was martyred. The latter, known also as Ḥájí Amín who succeeded him, lived to an old age and continued to be the Trustee of the Ḥuqúqu’lláh during the ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and part of that of the Guardian. The dominating factor in the lives of these two heroes of the Faith was a passionate love for Bahá’u’lláh. In order to enter the city they bought some camels and disguised themselves as Arabs. No one recognized them as Bahá’ís, and they were allowed in.

In the city they met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, and the news of their arrival was conveyed to Baha’u’lláh. Arrangements were made for them to meet Bahá’u’lláh in the public bath, but with the strict instructions that they show no signs of recognition or emotion. However, on beholding the face of his Beloved, Ḥájí Amín was so overwhelmed that his body began to tremble. He fell to the ground and hit his head on a stone, was badly injured, and was hurriedly carried out by his friend.

The arrival in ‘Akká of these two souls, and a few others who managed to get in afterwards, established a vital link between the Community of the Most Great Name and its exalted Founder, from Whom they were so cruelly cut off. Letters from the believers began to pour in, and Tablets were sent out. This process, which called for acts of sacrifice and heroism on the part of the many believers who risked their lives in order to maintain a two-way communication channel, continued throughout Bahá’u’lláh’s life. Men like Shaykh Salmán, honoured by the appellation of “the Messenger of the Merciful”, who in previous years had carried Bahá’u’lláh’s Tablets from ‘Iráq and Adrianople, continued in this arduous task, travelling on foot between ‘Akká and Persia, and, in the utmost poverty, eating mostly bread and onions for sustenance. This great hero of the Cause, though illiterate, stands out among the disciples of Bahá’u’lláh as one of the spiritual giants of this Dispensation.

BADÍ—THE HANDFUL OF DUST

About a year after Bahá’u’lláh’s arrival in ‘Akká, a young Persian, aged seventeen, by the name of Áqá Buzurg, disguised himself as an Arab and entered the city. Although his father, a survivor of the upheaval of Shaykh Ṭabarsí, had been a devoted Bahá’í, Áqá Buzurg had shown no interest in the Faith until he met Nabil in the city of Níshápúr, in northeast Persia, and was converted. He then decided to go and attain the presence of Bahá’u’lláh.

Upon his arrival in the city of ‘Akká in 1869 he began to roam around until he came to a mosque where he saw a few Persians and recognized the Master among them. He wrote a note, in which he declared his faith, and handed it to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Who greeted him warmly and took him along with the party straight to the barracks, where he was ushered into the presence of Bahá’u’lláh.

In a Tablet Mírzá Áqá Ján mentions that Áqá Buzurg was summoned twice to meet Bahá’u’lláh alone. It was in the course of these momentous audiences that the hands of Bahá’u’lláh created a new being and bestowed upon him the title of Badí‘ (i.e. wonderful). For more than two years Bahá’u’lláh had been waiting for a devoted soul to arise and deliver His Tablet to Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh of Persia. While in Adrianople He had written some passages on the cover of the Tablet, anticipating that the Almighty would cause one of His servants to arise, detach himself from all earthly things, adorn his heart with the ornament of courage and strength, take the Tablet, walk all the way to the capital of Persia, hand it in the manner described by Him to the King, and in the end be prepared to give his life, if necessary, with great joy and thankfulness. “We took a handful of dust,” is Bahá’u’lláh’s own testimony referring to Badí‘, “mixed it with the waters of might and power and breathed into it the spirit of assurance.”

In a Tablet revealed in honour of the father of Badí‘, who was also martyred a few years later, the Pen of the Most High, in great detail, portrays the manner in which this new creation came into being. He describes that when the appointed time had arrived the Tongue of Grandeur uttered “one word” which caused his whole being to tremble, and that were it not for God’s protection he would have been dumbfounded. Then the Hand of Omnipotence began creating the new creation, and “breathed into him the spirit of might and power”. So great had been the infusion of this might, as attested by Bahá’u’lláh, that, single and alone, Badí‘ could have conquered all that is on earth and in heaven. Bahá’u’lláh mentions that when this new creation came into being, Badí‘ had smiled in His presence and manifested such steadfastness that the Concourse on high was deeply moved and uplifted.

In the same Tablet, referring to the loftiness of the station of Badí‘, He states that no Tablet can convey its significance nor any pen describe its glory. Badí‘ left the Most Great Prison and went to Haifa. Baha’u’llah entrusted Ḥájí Sháh Muḥammad Amín (His Trustee) with a small case and a Tablet to be delivered into the hands of Badí‘ at Haifa. The following is the story as recounted by this Trustee to an eminent Bahá’í historian.

I was given a small case and was instructed to hand it to Badi‘ at Haifa together with some money. I did not know anything about the contents of the case. I met him at Haifa and gave him the glad tidings that he had been honoured with a trust . . . we left the town and walked up Mount Carmel where I handed him the case. He took it into his hands, kissed it, and knelt with his forehead to the ground; he also took the sealed envelope, walked twenty to thirty paces away from me, sat down facing ‘Akká, read it, and again knelt with his forehead to the ground. The rays of ecstasy and the signs of gladness and joy appeared on his face.

I asked him if I could read the Tablet also. He replied, ‘There is no time’. I knew it was a confidential matter. But what it was I had no idea—l could not imagine such a mission.

I mentioned that we had better go to Haifa, in order that, as instructed, I might give him some money. He declined to go with me, but suggested that I could go alone and bring it to him.

When I returned, in spite of much searching, I could not find him. He had gone. . . We had no news of him until we heard of his martyrdom in Ṭihrán. Then I knew that the case contained the Tablet of Bahá’u’lláh to the Sháh, and the sealed envelope, a holy Tablet containing the glad tidings of the future martyrdom of the one who was the essence of steadfastness and strength.

The same chronicler has written the following account given by a certain believer who met Badí‘ on his way to Persia and travelled with him for some distance.

. . he was very happy and smiling, patient, thankful, gentle, and humble. All that we knew was that he had attained the presence of Bahá’u’lláh and was now returning to his home in Khurásán. Many a time he could be seen to have walked about a hundred steps, leaving the road in either direction, turning his face towards ‘Akká, kneeling with his forehead to the ground and could be heard saying, ‘O God! Do not take back, through Thy justice, what Thou hast vouchsafed unto me through Thy bounty, and grant me the strength for its protection.’

Thus Badí‘ travelled on foot all the way to Ṭihrán and did not meet with anyone there. On arrival he discovered that the King was staying at his summer residence. He made his way to that area and sat on the top of the hill overlooking the Sháh’s palace at Níyávarán. The King on successive days, looking through his binoculars, saw the same man dressed in white, sitting in the same position on the hill. He ordered his men to find out who he was and what he wanted.

Badí‘ told them that he had a letter from a very important personage for the Sháh and must hand it personally to him. After searching him they brought him to the King.

Only those who are well versed in the history of Persia in the nineteenth century can appreciate the immense dangers which faced an ordinary person like Badí‘ wishing to meet a palace official, let alone the King. For at that time the King enjoyed absolute power and was surrounded by ruthless officials who would put to the sword anyone who would dare to utter one word, or raise a finger, against the established institutions of that oppressive regime. The loud voice of the “herald” who announced to the public in the streets the approach of the King’s carriage, shouting, “Everyone die! Everyone go blind!” would strike terror into the hearts of the citizens who, with eyes cast to the ground, stood motionless and still as their King and his men passed by.

Being invested by Bahá’u’lláh with tremendous powers, this young man of seventeen, assured and confident, stood straight as an arrow, face to face with the King. Calmly and courteously he handed him the Tablet and in a loud voice called out the celebrated Arabic phrase: “O King! I have come to thee from Sheba with a weighty message.”

The King sent the Tablet to the divines of Ṭihrán and commanded them to write an answer to Bahá’u’lláh. Finding themselves incapable of doing so, they evaded the issue and put forward some excuses which displeased the King immensely.

Badí‘ was arrested, and brutally tortured. His endurance and fortitude amazed the executioner and other officials. They took a photograph of him as he sat in front of a brazier containing hot bars of iron with which he was branded. Eventually his head was beaten to a pulp and his body thrown into a pit. This was July 1870.

For three years after the martyrdom of Badí‘, Bahá’u’lláh referred in His Tablets to his steadfastness and sacrifice, extolled his station, and bestowed upon him the title “Pride of Martyrs”.

THE TABLET TO THE SHÁH

For over two decades the people of Persia had witnessed memorable acts of heroism performed by a small band of God-intoxicated heroes, whose devotion and self-sacrifice had lit a great conflagration throughout that country. The Message of the Báb, the accounts of His martyrdom, and the transforming power of His Cause had already reached to every corner of that land; and from there its reverberations had echoed to the Western world. And yet, as attested by Bahá’u’lláh, not until this momentous Tablet was delivered to the King had the nature of the Cause of God or the claims of its Founder, or its principles and teachings, been clearly enunciated to those who held the reins of power in their hands.

In the annals of the Faith, Badí‘ stands out among the first heroic souls to arise for the proclamation of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh. He joyously sacrificed himself in His path.

This sacrifice was not in vain. The Cause of Bahá’u’lláh—which, from the time of its inception, had been suppressed; whose adherents in the land of its birth had been so cruelly persecuted and at times mowed down in thousands; whose very name, as anticipated by Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh and the divines of Persia, was to have been obliterated from the pages of history—has, in spite of much opposition, tremendously expanded during the last hundred years. Its light has been systematically diffused to all the continents of the world. The army of its pioneers and teachers, recruited from every race, class and colour, proclaiming to mankind the advent of the Lord of Hosts, has encircled the globe. The rising institutions of its divinely guided Administrative Order have been established, and within its World Centre, in the vicinity of its Holy Shrines, the crowning Edifice of that same Order (The Universal House of Justice)—the only refuge for the world’s tottering civilization —has been majestically erected.

This glorious unfoldment of the Cause in the Formative Age and its future sovereignty in the Golden Age are the direct consequences, on the one hand, of the outpourings of Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation and, on the other, of the mysterious power generated by the sacrifice of countless martyrs, whose precious blood has flowed in great profusion during the Heroic Age of the Faith.