Part II: The Process of Spiritual Growth

1. Prerequisites for Spiritual Growth

Spirituality is the process of the proper development of man’s innate spiritual capacities. But how does this process start and how is it carried on? What is the relationship between spiritual development and other kinds of development processes (e.g. format schooling)? Why do there seem to have been so few people who have thus conceived the purpose of their lives and dedicated themselves to the pursuit of spirituality? Answers to these and other similar questions are given in the Bahá’í Writings, but we need to proceed systematically to gain perspective.

Clearly the prime condition for embarking on the process of spiritual development is the awareness that the process is useful, necessary, and realistically possible: the individual must become fully alert to the objective existence of the spiritual dimension of reality. Since such spiritual realities as God, the soul, and the mind are not directly observable, man has no immediate access to them. He has only indirect access through the observable effects that these spiritual realities may produce. The Bahá’í Writings acknowledge this situation and affirm that the Manifestation (or Prophet) of God is the most important observable reality which gives man access to intangible reality:

The door of the knowledge of the Ancient of Days being thus closed in the face of all beings, the Source of infinite grace …hath caused those luminous Gems of Holiness to appear out of the realm of the spirit, in the noble form of the human temple, and be made manifest unto all men, that they may impart unto the world the mysteries of the unchangeable Being, and tell of the subtleties of His imperishable Essence. These sanctified Mirrors, these Day-springs of ancient glory are one and all the Exponents on earth of Him Who is the central Orb of the universe, its Essence and ultimate Purpose.1Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-Íqán (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Committee, 1954), pp. 99-100.

In another passage, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has said:

The knowledge of the Reality of the Divinity is impossible and unattainable, but the knowledge of the Manifestations of God is the knowledge of God, for the bounties, splendors and divine attributes are apparent in Them. Therefore, if man attains to the knowledge of the Manifestations of God, he will attain to the knowledge of God; and if he be neglectful of the knowledge of the Holy Manifestations, he will be bereft of the knowledge of God.2‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), p. 222.

Thus, the Manifestations constitute that part of observable reality which most readily leads man to the knowledge and awareness of the spiritual dimension of existence. Of course, only those living in the lifetime of a Manifestation can observe Him at first hand, but His revelation and His Writings constitute permanent observable realities which enable us to maintain objective content in our beliefs, concepts and practices:

Say: The first and foremost testimony establishing His truth is His own Self. Next to this testimony is His Revelation. For whoso faileth to recognize either the one or the other He hath established the words He hath revealed as proof of His reality and truth.3Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), p. 105.

Elsewhere in the Bahá’í Writings, it is explained that everything in observable reality, when properly perceived, reveals some aspect of God, its Creator. However, only a conscious, willing, intelligent being such as man can reflect (to whatever limited degree) the higher aspects of God. The Manifestations of God, being the “most accomplished, the most distinguished, and the most excellent”4Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), p. 179. of men, endowed by God with transhuman spiritual capacities, represent the fullest possible expression of the divine in observable reality.

Thus, the first step in the path of spiritual growth is to become as intensely aware as possible of the reality of the spiritual realm of existence. The principle key to such an awareness is knowledge of the Manifestations of God.

Indeed, since the Manifestations constitute such a unique link between man and the unseen world of spiritual reality, knowledge of the Manifestations is the foundation of the whole process of spiritual development.5In this regard, Bahá’u’lláh has said: ‘Neither the candle nor the lamp can be lighted through their own unaided efforts, nor can it ever be possible for the mirror to free itself from its dross. It is clear and evident that until a fire is kindled the lamp will never be ignited, and unless the dross is blotted out from the face of the mirror it can never represent the image of the sun nor reflect its light and glory.’ Gleanings, p. 66. He goes on to point out that the necessary ‘fire’ and ‘light’ are transmitted from God to man through the Manifestations. This is not to say that real spiritual progress cannot take place before one recognizes and accepts the Manifestation.6

In one of His works, Bahá’u’lláh describes the stage leading up to the acceptance of the Manifestations as ‘the valley of search.’ It is a period during which one thinks deeply about the human condition, seeks answers to penetrating questions, and sharpens and develops one’s capacities in preparation for their full use. It is a period of increasing restlessness and impatience with ignorance and injustice. However, the Bahá’í Writings do affirm that in order to progress beyond a certain level on the path of spirituality, knowledge of the Manifestation is essential. Sooner or later (in this world or the next), knowledge and acceptance of the Manifestation must occur in the life of each individual.

The question naturally arises as to what step or steps follow the recognition of the Manifestation. Here again Bahá’u’lláh is quite clear and emphatic:

The first duty prescribed by God for His servants is the recognition of Him Who is the Day Spring of His Revelation and the Fountain of His laws, Who representeth the Godhead in both the Kingdom of His Cause and the world of creation. Whoso achieveth this duty hath attained unto all good; and whoso is deprived thereof, hath gone astray, though he be the author of every righteous deed. It behoveth every one who reacheth this most sublime station, this summit of transcendent glory, to observe every ordinance of Him Who is the Desire of the world. These twin duties are inseparable. Neither is acceptable without the other.7Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), pp. 330-331.

Thus, even though the recognition of the Manifestation is described as equal to “all good,” recognition alone is not a sufficient basis for spiritual growth. The effort to conform oneself to the standards of behavior, thought, and attitude expressed by the various laws ordained by the Manifestation is also an intrinsic, inseparable part of the8Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stress that mankind has undergone a collective process of evolution by which it has now arrived at the threshold of maturity. God now requires more of man, in particular that he assume responsibility for the process of self-development: ‘For in this holy Dispensation, the crowning of bygone ages, and cycles, true Faith is no mere acknowledgement of the Unity of God, but the living of a life that will manifest all the perfections implied in such belief.’ ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Divine Art of Living (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 25. process. The idea that great effort is necessary to the prosecution of the spiritual growth process occurs throughout the Bahá’í Writings:

The incomparable Creator hath created all men from one same substance, and hath exalted their reality above the rest of His creatures. Success or failure, gain or loss, must, therefore, depend upon man’s own exertions. The more he striveth, the greater will be his progress.9Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), pp. 81-82.

Know thou that all men have been created in the nature made by God, the Guardian, the Self-Subsisting. Unto each one hath been prescribed a pre-ordained measure, as decreed in God’s mighty and guarded Tablets. All that which ye potentially possess can, however, be manifested only as a result of your own volition.10Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), p. 149.

… He hath entrusted every created thing with a sign of His knowledge, so that none of His creatures may be deprived of its share in expressing, each according to its capacity and rank, this knowledge. This sign is the mirror of His beauty in the world of creation. The greater the effort exerted for the refinement of this sublime and noble mirror, the more faithfully will it be made to reflect the glory of the names and attributes of God, and reveal the wonders of His signs and knowledge. …

There can be no doubt whatever that, in consequence of the efforts which every man may consciously exert and as a result of the exertion of his own spiritual faculties, this mirror can be so cleansed …as to be able to draw nigh unto the meads of eternal holiness and attain the courts of everlasting fellowship.11Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), p. 262.

Personal effort is indeed a vital prerequisite to the recognition and acceptance of the Cause of God. No matter how strong the measure of Divine grace, unless supplemented by personal, sustained and intelligent effort it cannot become fully effective and be of any real and abiding advantage.12Shoghi Effendi in The Bahá’í Life (Toronto: National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Canada, undated), p. 6.

This last statement, from Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith from 1921 until his death in 1957, makes clear that recognition of and faith in the Manifestation of God are not simply unidirectional “gifts” from God to man. Rather, both involve a reciprocal relationship requiring an intelligent and energetic response on the part of the individual. Nor is true faith based on any irrational or psychopathological impulse.13See ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Bahá’í World Faith, 2nd ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1956), pp. 382-383, where faith is defined to be conscious knowledge: “By faith is meant, first, conscious knowledge, and second, the practice of good deeds.” Of course, whenever man gains knowledge which contradicts his preconceived notions, he experiences inner conflict and may therefore initially perceive the new knowledge (and thus the new faith) as irrational in that it contradicts what he previously assumed to be true. But this initial perception is gradually overcome as continued experience further confirms the new knowledge, finally leading to an integration of the new with whatever was correct and healthy in the old. But this model of faith stands in significant contrast to the widely-held view that religious faith is essentially or fundamentally irrational (and blind) in its very nature.

2. The Nature of the Process

We have seen how the spiritual growth process may begin by acceptance of the Manifestation and obedience to his laws and principles. We need now to gain a measure of understanding of the nature of the process itself.

We have characterized spiritual growth as an educational process of a particular sort for which the individual assumes responsibility and by which he learns to feel, think, and act in certain appropriate ways. It is a process through which the individual eventually becomes the truest expression of what he has always potentially been.

Let us consider several further quotations from the Bahá’í Writings which confirm this view of the spiritual growth process.

Whatever duty Thou hast prescribed unto Thy servants of extolling to the utmost Thy majesty and glory is but a token of Thy grace unto them, that they may be enabled to ascend unto the station conferred upon their own inmost being, the station of the knowledge of their own selves.14Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), pp. 4-5.

Here the “duties” which God has prescribed for man are seen not as ends in themselves but rather as “tokens,” in other words, as symbols for and means towards another, ultimate end. This end is characterized as being a particular kind of knowledge, here called self-knowledge.

In the following, Bahá’u’lláh speaks similarly of self-knowledge:

O My servants! Could ye apprehend with what wonders of My munificence and bounty I have willed to entrust your souls, ye would, of a truth, rid yourselves of attachment to all created things, and would gain a true knowledge of your own selves—a knowledge which is the same as the comprehension of Mine own Being.15Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), pp. 326-327.

One significant aspect of this passage is that true knowledge of self is identified with knowledge of God. That knowledge of God is identical with the fundamental purpose of life for the individual is clearly stated by Bahá’u’lláh in numerous passages. For example:

The purpose of God in creating man hath been, and will ever be, to enable him to know his Creator and to attain His Presence. To this most excellent aim, this supreme objective, all the heavenly Books and the divinely-revealed and weighty Scriptures unequivocally bear witness.16Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), p. 70. See also note 9.

Thus, while acceptance of the Manifestation of God and obedience to His ordinances is a necessary step which each individual must accomplish at some point in the spiritual growth process, these and other such duties are means to an ultimate end which is described as true self-knowledge. This quality of self-knowledge is equated with knowledge of God, and knowledge of God is considered by Bahá’u’lláh as constituting the essential reason for man’s existence.

All of this would seem to say that religion, in the final analysis, represents a cognitive discipline of some sort. But what kind of cognitive discipline could involve the full development of all of man’s spiritual capacities, and not just the mind? What kind of knowledge is meant by the true knowledge of self and how can such knowledge be tantamount to knowledge of God?

Bahá’u’lláh gives the key to answering these important questions in an explicit statement clearly describing the highest form of knowledge and development accessible to man:

Consider the rational faculty with which God hath endowed the essence of man. Examine thine own self, and behold how thy motion and stillness, thy will and purpose, thy sight and hearing, thy sense of smell and power of speech, and whatever else is related to, or transcendeth, thy physical senses or spiritual perceptions, all proceed from, and owe their existence to, this same faculty.…

Wert thou to ponder in thine heart, from now until the end that hath no end, and with all the concentrated intelligence and understanding which the greatest minds have attained in the past or will attain in the future, this divinely ordained and subtle Reality, this sign of the revelation of the All-Abiding, All-Glorious God, thou wilt fail to comprehend its mystery or to appraise its virtue. Having recognized thy powerlessness to attain to an adequate understanding of that Reality which abideth within thee, thou wilt readily admit the futility of such efforts as may be attempted by thee, or by any of the created things, to fathom the mystery of the Living God, the Day Star of unfading glory, the Ancient of everlasting days. This confession of helplessness which mature contemplation must eventually impel every mind to make is in itself the acme of human understanding, and marketh the culmination of man’s development.17Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), pp. 164-165.

This passage seems to indicate that the ultimate form of knowledge available to man is represented by his total awareness of certain limitations which are inherent in his very nature or at least in the fundamental relationship between his nature and the phenomena of existence (including his own being and that of God). In particular, man must assimilate in some profound way the truth that the absolute knowledge of God and even of his own self lie forever beyond his reach. His realization of this truth is consequent to his having made a profound and accurate appraisal of his God-created capacities and potentialities. Thus, in the last analysis, true self-knowledge appears as a deep and mature knowledge of both the limitations and the capacities of the self. Let us recall that attaining to this knowledge is said to require strenuous effort on the part of man and to involve the development of “all the potential forces with which his inmost true self hath been endowed.”18Also quoted in Section 1.2. Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1971), p. 68.

To gain a broader perspective on this question, let us compare the self-knowledge described here with human knowledge in general, hoping that such a comparison will help us to understand more clearly what is particular to true self-knowledge. In general terms, a “knowing situation” involves a subjectivity (in this case that of man), some phenomenon which is the object of knowledge, and finally those means and resources which the subject can mobilize in order to obtain the understanding he seeks. If we agree to lump these last aspects of the knowing process under the general term “method,” we arrive at the following schema:

Quite clearly, the knowledge which is ultimately obtained from this process will depend on all three fundamental aspects of the knowing situation. It will depend on the nature of the phenomenon being studied (e.g., whether it is easily observable and accessible, whether it is complex or simple), on both the capacities and limitations of the knowing subject, and on the method used. In particular, the knowledge which results from this process will necessarily be relative and limited unless the knowing subject possesses some infallible method of knowledge. In this regard, it is important to note that the Bahá’í Writings stress repeatedly that human beings (other than the Manifestations) have no such infallible method of knowledge and that human understanding of all things is therefore relative and limited.19It is interesting that modern science and modern scientific philosophy take essentially the same view of human knowledge. I have elsewhere treated this theme at some length (see Bahá’í Studies, vol. 2, ‘The Science of Religion,’ 1980), but will not enter into the discussion of such questions here.

For example, in a talk given at Green Acre near Eliot, Maine in 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá discusses the different criteria “by which the human mind reaches its conclusions.”20He explicitly mentions sense experience, reason, inspiration or intuition, and scriptural authority. After a discussion of each criterion, showing why it is fallible and relative, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá states: “Consequently, it has become evident that the four criteria or standards of judgement by which the human mind reaches its conclusions are faulty and inaccurate.” He then proceeds to explain that the best man can do is to use systematically all of the criteria at his disposal.21‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace (Wilmette, Ill.: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), pp. 253-255.

In another passage, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá affirms:

Knowledge is of two kinds. One is subjective and the other objective knowledge—that is to say, an intuitive knowledge and a knowledge derived from perception.

The knowledge of things which men universally have is gained by reflection or by evidence—that is to say, either by the power of the mind the conception of an object is formed, or from beholding an object the form is produced in the mirror of the heart. The circle of this knowledge is very limited because it depends upon effort and attainment.22‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), p. 157.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá then explains that the first kind of knowledge, that which is subjective and intuitive, is the special consciousness of the Manifestations: “Since the Sanctified Realities, the supreme Manifestations of God, surround the essence and qualities of the creatures, transcend and contain existing realities and understand all things, therefore, Their knowledge is divine knowledge, and not acquired—that is to say, it is a holy bounty; it is a divine revelation.”23Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), pp. 157-158.

Here again we see that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá expresses the limited character of all human knowledge (in contrast to the unlimited knowledge of the Manifestations deriving from their special superhuman nature). In yet another passage ‘Abdu’l-Bahá puts the matter thus:

Know that there are two kinds of knowledge: the knowledge of the essence of a thing and the knowledge of its qualities. The essence of a thing is known through its qualities; otherwise, it is unknown and hidden.

As our knowledge of things, even of created and limited things, is knowledge of their qualities and not of their essence, how is it possible to comprehend in its essence the Divine Reality, which is unlimited?

… Knowing God, therefore, means the comprehension and the knowledge of His attributes, and not of His Reality. This knowledge of the attributes is also proportioned to the capacity and power of man; it is not absolute.24Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), pp. 220-221.

It would seem clear from these and other similar passages from the Bahá’í Writings that whatever distinctive characteristics the true knowledge of self (or, equivalently, the knowledge of God) may have, it does not differ from other forms of knowledge with regard to degree of certainty. It is not less certain than other forms of knowledge since all human knowledge (including the knowledge of God and of “created and limited things”) is relative and limited. Nor does it differ from these other forms of knowledge by being more certain, as is clear from the passage above and from the passages of Bahá’u’lláh previously cited.25Some mystics and religious philosophers have contended that our knowledge of God is absolute and for that reason superior to the relative and limited knowledge obtained by science. Such thinkers offer mysticism as an alternative discipline to science. It is important to realize that the Bahá’í Faith does not lend support to such a view. In particular, concerning the inherent limitations of the individual’s intuitive powers, however disciplined and well-developed. Shoghi Effendi has said: “With regard to your question as to the value of intuition as a source of guidance for the individual; implicit faith in our intuitive powers is unwise, but through daily prayer and sustained effort one can discover, though not always and fully, God’s Will intuitively. Under no circumstances, however, can a person be absolutely certain that he is recognizing God’s Will, through the exercise of his intuition. It often happens that the latter results in completely misrepresenting the truth, and thus becomes a source of error rather than of guidance …”

However, if we compare knowledge of God with other forms of knowledge, not from the point of view of degrees of certainty, but rather from the standpoint of the relationship between man as knowing subject on the one hand, and the phenomenon which is the object of study on the other, we can immediately see that there is a tremendous difference. In all sciences and branches of knowledge other than religion, the object of study is a phenomenon which is either inferior to man in complexity and subtlety (in the case of physics and chemistry) or on a level with man (in the case of biology, psychology, and sociology). In either case, for each of these sciences the human knower is in a position of relative dominance or superiority which enables him to manipulate to a significant degree the phenomenon being studied. We can successfully use these phenomena as instruments for our purposes. But when we come to knowledge of God, we suddenly find ourselves confronted with a phenomenon which is superior to us and which we cannot manipulate. Many of the reflexes and techniques learned in studying other phenomena no longer apply. Far from learning how to manipulate God, we must learn how to discern expressions of God’s will for us and respond adequately to them. It is we who must now become (consciously acquiescing) instruments for God’s26In particular, the Manifestations of God represent objective and universally accessible expressions of God’s will. Humanity’s interaction with the Manifestations provides an important opportunity to experience completely a phenomenon which man cannot manipulate or dominate. The Manifestations likewise provide a challenge to each individual’s capacity to respond adequately to the divine will. purposes.

Viewed in this perspective, the distinctive characteristic of knowing God, as compared with all other forms of human knowledge, is that the human knower is in a position of inferiority with respect to the object of knowledge. Rather than encompassing and dominating the phenomenon by aggressive and manipulative techniques, man is now encompassed by a phenomenon more powerful than himself.

Perhaps, then, one of the deep meanings of the true knowledge of self (which is equivalent to the knowledge of God) that we are here confronted with the task of learning novel, and initially unnatural, patterns of thought, feeling, and action. We must retrain ourselves in a wholly new way. We must not only understand our position of dependence on God, but also integrate that understanding into our lives until it becomes part of us, and indeed until it becomes us, an expression of what we are.

In other words, the full, harmonious, and proper development of our spiritual capacities means developing these capacities so that we may respond ever more adequately, and with increasing sensitivity and nuance, to the will of God: The process of spiritual growth is the process by which we learn how to conform ourselves to the divine will on ever deeper levels of our being.27Another important dimension of spirituality is service to the collectivity. The development of one’s spiritual and material capacities makes one a more valuable servant. More will be said about this in a later section.

From this viewpoint, conscious dependence upon God and obedience to His will is not a capitulation of individual responsibility, a sort of helpless “giving up,” but rather an assumption of an even greater degree of responsibility and self-control. We must learn through deep self-knowledge, how to be responsive to the spirit of God.

The ability to respond to God in such a whole-hearted, deeply intelligent and sensitive way is not part of the natural gift of any human being. What is naturally given to us is the capacity, the potential to attain to such a state. Its actual achievement, however, is consequent only to a persistent and strenuous effort on our part. The fact that such effort, and indeed suffering, are necessary to attain this state of spirituality makes life often difficult.28Concerning the necessity of such suffering in the pursuit of spirituality, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has said: “Everything of importance in this world demands the close attention of its seeker. The one in pursuit of anything must undergo difficulties and hardships until the object in view is attained and the great success is obtained. This is the case of things pertaining to the world. How much higher is that which concerns the Supreme Concourse!” Divine Art of Living, p. 92. But the fact that it is truly possible makes of life a spiritual adventure a hundredfold more exciting than any other physical or romantic adventure could ever possibly be.

George Townshend, a Bahá’í renowned for the spiritual quality of his personal life, has given a description of this state of spiritual-mindedness. One senses that Townshend’s statement is based on deep personal experience as well as intelligent contemplation:

When the veils of illusion which hide a man’s own heart from himself are drawn aside, when after purgation he comes to himself and attains self-knowledge and sees himself as he truly is, then at the same moment and by the same act of knowledge he beholds there in his own heart His Father who has patiently awaited His son’s return.

Only through this act of self-completion, through this conclusion of the journey which begins in the kingdom of the senses and leads inward through the kingdom of the moral to end in that of the spiritual, does real happiness become possible. Now for the first time a man’s whole being can be integrated, and a harmony of all his faculties be established. Through his union with the Divine Spirit he has found the secret of the unifying of his own being. He who is the Breath of Joy becomes the animating principle of his existence. Man knows the Peace of God.29George Townshend, The Mission of Bahá’u’lláh (Oxford: George Ronald, 1952), pp. 99-100.

One of Bahá’u’lláh’s major works, The Book of Certitude, is largely devoted to a detailed explanation of the way in which God has provided for the education of mankind through the periodic appearance in human history of a God-sent Manifestation or Revelator. At one point in His discussion of these questions, Bahá’u’lláh gives a wonderfully explicit description of the steps and stages involved in the individual’s progress towards full spiritual development. This portion of The Book of Certitude has become popularly known among Bahá’ís as the “Tablet to the True Seeker,” although Bahá’u’lláh does not Himself designate the passage by this or any other appellation.

In general terms, a “true seeker” is anyone who has become aware of the objective existence of the spiritual dimension of reality, has realized that spiritual growth and development constitute the basic purpose of existence, and has sincerely and seriously embarked on the enterprise of fostering his spiritual progress. It is quite clear from the context of the passage that Bahá’u’lláh is primarily addressing those who have already reached the stage of accepting the Manifestation of God and obeying His commandments.

Bahá’u’lláh begins by describing in considerable detail the attitudes, thought patterns, and behavior patterns that characterize a true seeker. He mentions such things as humility, abstention from backbiting and vicious criticism of others, kindness and helpfulness to those who are poor or otherwise in need, and the regular practice of the discipline of prayer and of meditation. He concludes this description by saying “These are among the attributes of the exalted, and constitute the hall-mark of the spiritually-minded …When the detached wayfarer and sincere seeker hath fulfilled these essential conditions, then and only then can he be called a true seeker.”30Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-Íqán (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Committee, 1954), p. 195. He then continues by describing both the quality of effort necessary to the attainment of spirituality and the state of being which this attainment secures to the individual:

Only when the lamp of search, of earnest striving, of longing desire, of passionate devotion, of fervid love, of rapture, and ecstasy, is kindled within the seeker’s heart, and the breeze of His loving-kindness is wafted upon his soul, will the darkness of error be dispelled, the mists of doubts and misgivings be dissipated, and the lights of knowledge and certitude envelop his being. At that hour will the mystic Herald, bearing the joyful tidings of the Spirit, shine forth from the City of God resplendent as the morn, and, through the trumpet-blast of knowledge, will awaken the heart, the soul, and the spirit from the slumber of negligence. Then will the manifold favors and outpouring grace of the holy and everlasting Spirit confer such new life upon the seeker that he will find himself endowed with a new eye, a new ear, a new heart, and a new mind. He will contemplate the manifest signs of the universe, and will penetrate the hidden mysteries of the soul. Gazing with the eye of God, he will perceive within every atom a door that leadeth him to the stations of absolute certitude. He will discover in all things the mysteries of divine Revelation and the evidences of an everlasting manifestation.31Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-Íqán (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Committee, 1954), pp. 195-196. Bahá’u’lláh’s reference in the passage to ‘absolute certitude’ might be perceived at first as contradicting the strong statements regarding the limitations on human knowledge which we have earlier quoted. However, this superficial perception is relieved when we reflect that ‘certitude’ refers to a (psychological) state of being whereas the notion of ‘degree of certainty’ (and in particular the question of whether knowledge is relative or absolute) is concerned rather with the criteria of verification available to man as knowing subject. Thus, Bahá’u’lláh would seem to be saying that man can attain to a sense of absolute certitude even though his criteria of verification, and thus his knowledge, remain limited. Also, it is clear that such phrases as ‘the eye of God’ should be taken metaphorically and not literally. This metaphor, together with other such phrases as ‘new life’ and ‘absolute certitude,’ convey a strong sense of the discontinuity between the respective degrees of understanding possessed by the individual before and after his attainment of true self-knowledge.

Nor should the achievement of such a degree of spiritual development be considered an ideal, static configuration from which no further change or development is possible, as the following two passages from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá make clear:

As the divine bounties are endless, so human perfections are endless. If it were possible to reach a limit of perfection, then one of the realities of the beings might reach the condition of being independent of God, and the contingent might attain to the condition of the absolute. But for every being there is a point which it cannot overpass—that is to say, he who is in the condition of servitude, however far he may progress in gaining limitless perfections, will never reach the condition of Deity. …

For example, Peter cannot become Christ. All that he can do is, in the condition of servitude, to attain endless perfections …32‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), pp. 230-231.

Both before and after putting off this material form, there is progress in perfection but not in state…. There is no other being higher than a perfect man. But man when he has reached this state can still make progress in perfections but not in state because there is no state higher than that of a perfect man to which he can transfer himself. He only progresses in the state of humanity, for the human perfections are infinite. Thus, however learned a man may be, we can imagine one more learned.

Hence, as the perfections of humanity are endless, man can also make progress in perfections after leaving this world.33‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), p. 237.

3. The Dynamics of the Spiritual Growth Process

After contemplating Bahá’u’lláh’s description of the state of being resulting from the attainment of true self- knowledge, it would be only natural to wish that this state could be achieved instantaneously, perhaps through some supreme gesture of self-renunciation, or whatever. However, the Writings of the Bahá’í Faith make it plain that this is not possible. By its very nature, true spirituality is something which can only be achieved as the result of a certain self-aware and self- responsible process of development.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá often responded to Bahá’ís who felt overwhelmed by the task of refining their character by stressing the necessity of patience and daily striving. “Be patient, be as I am,” He would say.34The Dynamic Force of Example (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 50. Spirituality was to be won “little by little; day by day.”35The Dynamic Force of Example (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 51. And again:

He is a true Bahá’í who strives by day and by night to progress and advance along the path of human endeavor, whose most cherished desire is to live and act as to enrich and illuminate the world, whose source of inspiration is the essence of Divine virtue, whose aim in life is so to conduct himself as to be the cause of infinite progress. Only when he attains unto such perfect gifts can it be said of him that he is a true Bahá’í.36Divine Art of Living (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 25.

This last passage in particular would seem to indicate that one of the signs of an individual’s maturity is his acceptance of the gradual nature of the process of spiritual growth and of the necessity for daily striving. Indeed, psychology has established that one important measure of maturity is the capacity to delay gratification, i.e., to work for goals whose attainment is not to be had in the short term. Since spirituality is the highest and most important goal anyone can possibly have, it is natural that its achievement should call forth the greatest possible maturity on the part of the individual.37This point of view on spirituality is in sharp contrast with the viewpoint found in many contemporary cults and sects which stress instant gratification and irresponsibility in the name of honesty and spontaneity.

In a similar vein, Shoghi Effendi has said that the Bahá’ís:

… should not look at the depraved condition of the society in which they live, nor at the evidences of moral degradation and frivolous conduct which the people around them display. They should not content themselves merely with relative distinction and excellence. Rather they should fix their gaze upon nobler heights by setting the counsels and exhortations of the Pen of Glory as their supreme goal. Then it will be readily realized how numerous are the stages that still remain to be traversed and how far off the desired goal lies—a goal which is none other than exemplifying heavenly morals and virtues.38The Bahá’í Life (Toronto: National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Canada, undated), p. 2.

In describing the experience of the individual as he progresses towards this goal, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has said: “Know thou, verily, there are many veils in which the Truth is enveloped; gloomy veils; then delicate and transparent veils; then the envelopment of Light, the sight of which dazzles the eyes. …”39Divine Art of Living (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 51. Indeed, one of Bahá’u’lláh’s major works, The Seven Valleys, describes in poetic and powerfully descriptive language the different stages of spiritual perception through which an individual may pass in his efforts to attain to the goal of spirituality.40Bahá’u’lláh, The Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Committee, rev. ed., 1954). In the Tablet of Wisdom, Bahá`u’lláh says simply: “Let each morn be better than its eve and each morrow richer than its yesterday.”41Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh (Haifa, Israel: compiled by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, 1978), p. 138. Elsewhere, Bahá’u’lláh has urged man to live in such a way that each day his faith increases over the previous day. All of these passages strongly reinforce the notion that spirituality is to be won only through a gradual process and is not to be attained by any once-and-for-all act of faith.

We want now to understand the dynamics of this process. How do we even take one step forward? Also, we need to understand how a gradual process can produce a change as radical as that described by Bahá’u’lláh in the passage quoted in the previous section (see note 41).

The answer to this last consideration is that the rate of change produced by the process is not constant. In technical language, the process is exponential and not linear. To say that a growth process is linear means that the rate of growth is unchanging. In an exponential process, on the other hand, the rate of growth is very small in the beginning but gradually increases until a sort of saturation point is reached. When this point is passed, the rate of growth becomes virtually infinite, and the mechanism of the process becomes virtually automatic. There is, so to speak, an “explosion” of progress.42In an exponential process, the rate of growth at any given stage of the process is directly proportional to the total growth attained at that stage. Thus, as the process develops and progress is made, the rate of progress increases. An example would be a production process such that the total amount produced at any given stage is double the total amount produced at the previous stage (imagine a reproduction process in which bacteria double each second, starting with one bacterium). Since the double of a large number represents a much greater increase than the double of a small number, doubling is an example of an exponential law of progress. As we examine the dynamics of the process of spiritual development we will see precisely how the exponential nature of the process can be concretely understood. Let us turn, then, to an examination of these dynamics.

The main problem is to understand how the various capacities of the individual—mind, heart, and will—are to interact in order to produce a definite step forward in the path towards full development. Basic to our understanding of this obviously complex interaction are two important points that Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá both stress regarding the growth process. The first is that no one faculty acting alone is sufficient to produce results.43Bahá’u’lláh has stressed that the merit of all deeds is dependent upon God’s acceptance (cf. A Synopsis and Codification of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas of Bahá’u’lláh, [Haifa, Israel: the Universal House of Justice, 1973], p. 52), and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has said that “good actions alone, without the knowledge of God, cannot be the cause of eternal salvation, everlasting access, and prosperity, and entrance into the Kingdom of God.’ Some Answered Questions, p. 238. On the other hand, knowledge without action is also declared to be unacceptable: ’Mere knowledge of principles is not sufficient. We all know and admit that justice is good but there is need of volition and action to carry out and manifest it.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Foundations of World Unity (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1945). p, 26. At the same time, love and sincere good intentions alone are also insufficient for spiritual progress, for they need to be guided by knowledge and wisdom and expressed through action. Moreover, without true self-knowledge we may sometimes mistake physical attraction or self-centered emotional need as love and act upon it with negative results. The second point is that there is a hierarchical relationship between these faculties in which knowledge is first, love is second, and will is third. Let us discuss each of these points in turn.

As we have seen in Section 1 on the nature of man, each individual has certain basic, innate spiritual capacities, but in a degree and in a proportion which are unique to him. Moreover, the initial development of these innate capacities takes place under conditions over which the individual has very little control (e.g., the conditions of the family into which he is born, the social and physical surroundings to which he is exposed). An important consequence of this universal, existential situation is that each one of us arrives at the threshold of adulthood having developed a more or less spontaneous and unexamined pattern of responses to life situations. This pattern, unique to each individual, is an expression of his basic personality at that stage of his development.44At this point in our development, it is difficult if not impossible to know how much of our mode of functioning is due to our innate qualities and how much is due to the cumulative influence of external conditions. Thus, our spontaneous response pattern may be a reasonably authentic expression of our true selves or it may contain significant distortions. It is only by moving on to the next stage of self-aware, self-directed growth that we can gain insight into this question.

Given the limited and relative nature of our innate spiritual capacities as well as the conditions under which they will have developed up to this point in our lives, our personal response pattern will necessarily involve many imbalances, immaturities and imperfections. Moreover, because of the largely spontaneous and unselfconscious nature of our pattern, we will be unaware of many aspects of it. Thus, our attainment of true self-knowledge will involve our becoming acutely aware of the internal psychic mechanisms of our response pattern. We must take stock of both the strengths and the weaknesses of our pattern and make deliberate efforts to bring it into harmony, balance, and full development. We must also begin to correct false or improper development.

This is the beginning of a transformation or growth process for which we assume responsibility. Until this point in our lives, our growth and development has been primarily in the hands of others. Though we have collaborated in the process with some degree of consciousness, nevertheless the major part has been beyond our control and indeed beyond our awareness. We have been the relatively passive recipients of a process to which we have been subjected by others. Now we must become the agents and prime movers of our own growth process. This self-directed process is a continuation of the previously unconscious one, but it represents a new and significant stage in our lives.

This new, self-directed growth process is going to take time. Moreover, it is sometimes going to be painful, and in the beginning stages at least, very painful. The new, more balanced functioning for which we begin to strive will appear at first to be unnatural since the spontaneous pattern we will have previously developed is the natural expression of our (relatively undeveloped and immature) selves.

In fact, one of the major problems involved in starting the process of spiritual growth is that we initially feel so comfortable with our spontaneous and unexamined mode of functioning. This is why it often happens that an individual becomes strongly motivated to begin the spiritual growth process only after his spontaneous system of coping has failed in some clear and dramatic way.

The realization that failure has occurred may come in many different forms. Perhaps we are faced with a “test,” a life situation that puts new and unusual strain on our defective response system and thus reveals to us its weakness. We may even temporarily break down, i.e., become unable to function in situations which previously caused no difficulties. This is because we have become so disillusioned by our sudden realization of our weakness that we put the whole framework of our personalities into doubt. Perceiving that things are wrong, but not yet knowing just how or why, we suspend activity until we can gain perspective on what is happening.45If a person has been fortunate in the quality of spiritual education he has received during his formative years, his spontaneous system of functioning may be very good indeed compared with others in less fortunate circumstances. If his spiritual education has been especially good, he will have already learned and understood the necessity of assuming the responsibility for his own spiritual growth process (and will have already begun to do so as an adolescent). In such cases as these, the individual will not need any test or dramatic setback in order to awaken him to spiritual realities of which he is already aware. Indeed, the Bahá’í Writings explain that the very purpose of the spiritual education of children and youth is to lead them to such an understanding of spiritual realities that, upon reaching adulthood, they will be naturally equipped to take charge of their own lives and spiritual growth processes. Spiritual education of this quality is extremely rare (in fact virtually nonexistent) in our society today, but the Bahá’í Writings contain many principles and techniques for the spiritual education of children and affirm that the application of these principles will, in the future, enable the majority of people to attain the age of adulthood with a clear understanding of the dynamics of the spiritual growth process. Though this state of affairs will not eliminate all human suffering (in particular suffering which comes from physical accident or certain illnesses), it will eliminate that considerable proportion of human suffering which is generated by the sick, distorted, and destructive response patterns and modes of functioning widespread in current society.

Or, the perception of the inadequacy of our spontaneous system of functioning may result from our unanticipated failure at some endeavor. We are then led to wonder why we anticipated a success that we were unable to deliver.46The answer may be that our expectations were unreasonable to begin with. In this way, failure to obtain some particular external goal can lead to success in gaining valid knowledge and insight into our internal processes, thus fostering spiritual growth. Indeed, there is very little that happens to us in life that cannot be used to give us new self-insight and hence contribute to fulfilling the basic purpose of prosecuting the spiritual growth process. It sometimes happens that a person whose spontaneous level of functioning is quite weak and defective is soon led to discover this fact while a person whose spontaneous level of functioning is rather high (due to favorable circumstances in early life or to exceptional natural endowments) persists for many years in his spiritually unaware state, making no spiritual progress whatever. In this way, the person whose spontaneous level of functioning is weak may take charge of his growth process much sooner than others and thereby eventually surpass those with more favorable natural endowments or initial life circumstances.

The frequency with which the perception of inadequacy and the consequent motivation to change is born through fiery ordeal has led some to build a model of spiritual growth in which such dramatic failures and terrible sufferings are considered to be unavoidable and necessary aspects of the growth process. The Bahá’í Writings would appear to take a middle position on this question. On the one hand, they clearly affirm that tests, difficulties, and sufferings are inevitable, natural concomitants of the spiritual growth process. Such painful experiences, it is explained, serve to give us deeper understanding of certain spiritual laws upon which our continued growth depends.47Regarding the spiritual meaning and purpose of suffering, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has said: “Tests are benefits from God, for which we should thank Him. Grief and sorrow do not come to us by chance, they are sent to us by the Divine mercy for our own perfecting … The mind and spirit of man advance when he is tried by suffering … suffering and tribulation free man from the petty affairs of this worldly life until he arrives at a state of complete detachment. His attitude in this world will be that of divine happiness … Through suffering (one) will attain to an eternal happiness which nothing can take from him … To attain eternal happiness one must suffer. He who has reached the state of self-sacrifice has true joy. Temporal joy will vanish.” Divine Art of Living, pp. 89-90. On the other hand, many instances of human suffering are simply the result of careless living and are therefore potentially avoidable. Bahá’ís are taught to pray to God for preservation from violent or extreme tests. Moreover, the Bahá’í Writings strictly forbid asceticism and any other similar philosophies or disciplines which incite the individual actively to seek pain or suffering in the path of spiritual growth. The growth process itself involves enough pain without our seeking more through misguided or thoughtless living. But the deep sufferings and dramatic setbacks are potentially there for everyone who feels inclined to learn the hard way.48Naturally, it is heartening to see examples of murderers, thieves, rapists, or drug addicts who turn themselves around and become useful members of society and occasionally morally and intellectually superior human beings. But one can also deplore the fact that people with such potential and talents must waste so many years and cause so much suffering to themselves and others before realizing their potential.

Of course, even dramatic failures and sufferings may sometimes not be enough to convince us of our weaknesses and immaturities. We may put up various “defenses,” i.e., we may resist seeing the truth of the matter even when it is plain to everyone but ourselves. We engage in such strategies of self-illusion primarily when, for whatever reason, we find some particular bit of self-revelation unusually hard to take. If we do not learn the lesson from the situation, we may blindly and adamantly persist in the same behavior or thought patterns which continue to produce new and perhaps even more painful situations. We are then in a “vicious circle” in which our resistance to accepting the truer picture of reality actually increases with each new bit of negative feedback. Regarding such vicious circle situations, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has said:

Tests are a means by which a soul is measured as to its fitness, and proven out by its own acts. God knows its fitness beforehand, and also its unpreparedness, but man, with an ego, would not believe himself unfit unless some proof were given to him. Consequently his susceptibility to evil is proven to him when he falls into tests, and the tests are continued until the soul realizes its own unfitness, then remorse and regret tend to root out the weakness.49Quoted in Daniel Jordan, The Meaning of Deepening (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1973), p. 38.

Let us sum up. We start the process of conscious spiritual development by becoming aware of how we function at our present level of maturity. We assess as realistically as possible the level of intellectual, emotional, and behavioral maturity we have attained at present. As we perceive imbalanced development, underdevelopment, or improper development, we begin the job of correcting the perceived inadequacies.

It is at this stage, in particular, that the Bahá’í view of the nature of man becomes so important in fostering our spiritual growth and progress.50Of course, if our parents and educators have also had the Bahá’í viewpoint of the nature of man, this will have contributed to our development during our formative years. However, our future growth and development will depend on whatever attitudes and viewpoints we personally maintain. Nevertheless, we will continue to be significantly affected by our interactions with others and therefore by the attitudes and viewpoints which they have. More will be said about this point in a later section. Suppose we perceive, for example, that we have a tendency to be very willful, aggressive, and dominant in our relations with others. From the Bahá’í viewpoint, we would not consider the negative features of this pattern as inherently evil or sinful or as arising from some evil part of ourselves, a part which must be despised and suppressed. We are free to recognize the positive potential of this aspect of our character. After examination, we might find that we have not sufficiently developed our feeling capacity and are, therefore, sometimes insensitive to the needs and feelings of others. Or perhaps we often act impulsively and need to develop also our understanding capacity so as to act more reflectively and wisely. Or again, we might find that our mode of relating to others represents an attempt to satisfy in an illegitimate way some need within us (a need for security or self-worth perhaps) that we have not succeeded in meeting legitimately. We will then understand that we have been engaging in an improper (and unproductive) use of will and must, therefore, set about redeploying our psychic forces in a more productive manner. As we gradually succeed in doing this, we will satisfy our inner need legitimately and improve our relationships with others at the same time.51Of course, if our parents and educators have also had the Bahá’í viewpoint of the nature of man, this will have contributed to our development during our formative years. However, our future growth and development will depend on whatever attitudes and viewpoints we personally maintain. Nevertheless, we will continue to be significantly affected by our interactions with others and therefore by the attitudes and viewpoints which they have. More will be said about this point in a later section.

In other words, the model of human spiritual and moral functioning offered by the Bahá’í Faith enables us to respond creatively and constructively once we become aware that change is necessary. We avoid wasting precious energy on guilt, self-hatred, or other such unproductive mechanisms. We are able to produce some degree of change almost immediately. This gives us positive feedback, makes us feel better about ourselves, and helps generate courage to continue the process of change we have just begun.

We now come to the important question of the mechanism by which we can take a step forward in the path of spiritual progress. What we need to consider is the hierarchical relationship between knowledge, love, and action.

4. Knowledge, Love, and Will

A close examination of the psychology of the spiritual growth process as presented in the Bahá’í Writings indicates that the proper and harmonious functioning of our basic spiritual capacities depends on recognizing a hierarchical relationship among them. At the apex of this hierarchy is the knowing capacity.

First and foremost among these favors, which the Almighty hath conferred upon man, is the gift of understanding. His purpose in conferring such a gift is none other except to enable His creature to know and recognize the one true God—exalted be His glory. This gift giveth man the power to discern the truth in all things, leadeth him to that which is right, and helpeth him to discover the secrets of creation. Next in rank, is the power of vision, the chief instrument whereby his understanding can function. The senses of hearing, of the heart, and the like, are similarly to be reckoned among the gifts with which the human body is endowed. … These gifts are inherent in man himself. That which is preeminent above all other gifts, is incorruptible in nature, and pertaineth to God Himself, is the gift of Divine Revelation. Every bounty conferred by the Creator upon man, be it material or spiritual, is subservient unto this.52Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust), 1971, pp. 194-195.

In the last chapter of Some Answered Questions, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá elaborates even further on this theme. He explains that right actions and moral behavior are not in themselves sufficient for spirituality. Alone, such actions and behavior constitute “… a body of the greatest loveliness, but without spirit.”53Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), p. 300-302. He then explains: “. . . that which is the cause of everlasting life, eternal honor, universal enlightenment, real salvation and prosperity is, first of all, the knowledge of God.”54‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), p. 300-302. He continues, affirming: “Second, comes the love of God, the light of which shines in the lamp of the hearts of those who know God …”55‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), p. 300-302. and “The third virtue of humanity is the goodwill which is the basis of good actions . . . though a good action is praiseworthy, yet if it is not sustained by the knowledge of God, the love of God, and a sincere intention, it is imperfect.”56‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1981), p. 300-302.

In another passage, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá expresses the primacy of knowledge with respect to action as follows: “Although a person of good deeds is acceptable at the Threshold of the Almighty, yet it is first “to know” and then “to do”. Although a blind man produceth a most wonderful and exquisite art, yet he is deprived of seeing it…. By faith is meant, first, conscious knowledge, and second, the practice of good deeds.”57‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Bahá’í World Faith (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1956), pp. 382-383. In yet another passage, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá describes the steps towards the attainment of spirituality:

By what means can man acquire these things? How shall he obtain these merciful gifts and powers? First, through the knowledge of God. Second, through the love of God. Third, through faith. Fourth, through philanthropic deeds. Fifth, through self-sacrifice. Sixth, through severance from this world. Seventh, through sanctity and holiness. Unless he acquires these forces and attains to these requirements he will surely be deprived of the life that is eternal.58Divine Art of Living (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1974), p. 19.

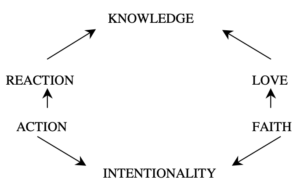

In the above passages, and in many others not quoted, the hierarchical ordering of spiritual faculties is the same: Knowledge leads to love which generates the courage to act (i.e., faith) which forms the basis of the intention to act (i.e., motive and good will) which in turn leads to action itself (i.e., good deeds).Of course, the knowledge which starts this psycho-spiritual chain reaction is not just any kind of knowledge, but the knowledge of God which is equivalent to true self-knowledge.

As we begin to take charge of our own spiritual growth process, one of the main problems we face is that our existing perception of ourselves—of what we are and of what we should be—is bound to be distorted and inadequate in various ways, for his self-perception (or self-image) is the very basis of the spontaneous response pattern we have inherited from our childhood and early youth. Indeed, our mode of functioning at any given stage of our development is largely just a dramatization of our basic self-image; it is the projection of this self-image onto the various life situations we encounter. Thus, our self-image is, in many ways, the key to our personalities.

In any case, to the degree that our self-concept is false we will experience unpleasant tensions and difficulties as we become involved in various life situations. The false or unrealistic parts of our self-image will be implicitly judged by our encounter with external reality. We will sense this and begin to perceive, at first vaguely and uncomfortably but then more sharply, that something is wrong. Even though this feedback information from external reality may be from neutral sources and devoid of any value-judgemental quality, we may nevertheless perceive it as a threat or even an attack. If the feedback is not neutral but comes, say, in the form of blatantly negative criticism from others, our sense of being threatened will certainly be much greater.

Moreover, we will perceive the source of these threats as being somewhere outside ourselves. It will not naturally occur to us that the source lies rather within ourselves in the form of an illusory and unrealistic self-concept. Therefore, our instinctive reaction to the negative feedback information will be to resist, to defend our self-image and to strive to maintain it. In defending our self-image, we believe we are defending our selves because we do not view ourselves as a mosaic of true and false, real and unreal. We see only the seamless, undifferentiated whole of “I” or “me.” The result is that we begin to bind up more and more of our psychic energies in the defence of our self- image. We confuse egotistic pride, which is our attachment to our limited and distorted self-concept, with self- respect and honour, which are expressions of the deep spiritual truth that we are created in the image of God with an intrinsic value given by Him and without any essentially evil or sinful part.

The “binding energy” involved in our defence of our self-concept is frequently experienced as various negative emotions like fear, rage, jealousy, or aggression. These emotions are all expressions of our attempt to locate the source of our irritation outside ourselves in objective, external reality. We are also liable to experience considerable anxiety as we cling more and more desperately to whatever false part of ourselves we cannot relinquish. Clearly, the greater the pathology of our self-image and the greater our attachment to it, the stronger will be our sense of being threatened and attacked, and the greater will be the amount of psychic energy necessary to maintain and defend the false part of our self-image.

At this point, an increase in self-knowledge will be represented by some insight into ourselves which enables us to discard a false part of our self-image. This act of self-knowledge is the first stage in the mechanism involved in taking a single step forward in the process of spiritual growth. Such an increment in self-knowledge has one immediate consequence: It instantly releases that part of our psychic energy which was previously bound up in defending and maintaining the false self-concept. The release of this binding energy is most usually experienced as an extremely positive emotion, a sense of exhilaration and of liberation. It is love. We have a truer picture of our real (and therefore God-created) selves, and we have a new reservoir of energy which is now freed for its God-intended use in the form of service to others.

Following this release of energy will be an increase in courage. We have more courage partly because we have more knowledge of reality and have therefore succeeded in reducing, however slightly, the vastness of what is unknown and hence potentially threatening to us. We also have more courage because we have more energy to deal with whatever unforeseen difficulties may lie ahead. This new increment of courage is an increase in faith.

Courage generates within us intentionality, i.e., the willingness and the desire to act. We want to act because we are anxious to experience the sense of increased mastery that will come from dealing with life situations which previously appeared difficult or impossible but which now seem challenging and interesting. And we are also eager to seek new challenges, to use our new knowledge and energy in circumstances we would have previously avoided. And, most importantly, we have an intense desire to share with others, to serve them and to be an instrument, to whatever possible extent, in the process of their spiritual growth and development.

Finally, this intentionality, this new motivation, expresses itself in concrete action. Until now everything has taken place internally, in the inner recesses of our psyche. No external observer could possibly know that anything significant has taken place. But when we begin to act, the reality of this inner process is dramatized. Action, then, is the dramatization of intentionality and therefore of knowledge, faith, and love. It is the visible, observable concomitant of the invisible process that has occurred within us.

We have taken a step forward in our spiritual development. We have moved from one level to another. However small the step may be, however minimal the difference between the old level of functioning and the new, a definite transition has taken place.

Whenever we act, we affect not only ourselves but also our physical and social environment. Our action thereby evokes a reaction from others. This reaction is, of course, just a form of the feedback information mentioned above. But the difference is that our action has now been the result of a conscious and deliberate process. We know why we acted the way we did. Thus, we will perceive the reaction in a different way, even if it is negative (our good intentions certainly do not guarantee that the reaction will be positive). We will welcome the reaction because it will help us evaluate our actions. In short, the reaction to our actions will give us new knowledge, new self-insight. In this way, the cycle starts again and the process of taking another step along the path of spiritual growth is repeated. We represent this by the following diagram:

As is the case with any new discipline, so it is with learning spiritual growth. Our first steps forward are painfully self-conscious and hesitant. We are acutely aware of each detail, so much so that we wonder whether we will ever be able to make it work. We are elated at our first successes, but we tend to linger on the plateaus, becoming sufficiently motivated to take another step only when negative pressures begin to build up intolerably, forcing us to act.

Yet, as we pursue the process, we become more adept at it. Gradually, certain aspects become spontaneous and natural (not unconscious). They become part of us to the point of being reflex actions. The feedback loop resulting from our actions becomes more and more automatic. The rate of progress begins to pick up. The steps merge imperceptibly. Finally, the process becomes almost continuous. In other words, the rate of progress increases as we go along because we are not only making progress but also perfecting our skill at making progress.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá has said:

It is possible to so adjust one’s self to the practice of nobility that its atmosphere surrounds and colours every act. When actions are habitually and conscientiously adjusted to noble standards, with no thought of the words that might herald them, then nobility becomes the accent of life. At such a degree of evolution one scarcely needs try any longer to be good—all acts are become the distinctive expression of nobility.59‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Star of the West, Vol. 17, p. 286.

A process in which the rate of progress is proportional to the amount of progress made is exponential (see note 52). Thus, an analysis of the mechanism of the spiritual growth process allows us to understand why this process, though remaining a gradual one, is exponential: It is because we perfect the process of growing spiritually as we grow, thereby increasing the rate at which growth occurs.

The above diagram, and the detailed analysis of each stage of the mechanism involved in the hierarchical relationship between knowledge, love, and will, should not lead us to forget the other fundamental point, namely that all of our spiritual faculties must function together at each stage of the mechanism. In order to gain self-insight, we must will to know the truth about ourselves, and we must be attracted towards the truth. When we act, we must temper our actions with the knowledge and wisdom we have already accumulated at that given point in our development.

Moreover, when we begin the process of conscious, self-directed spiritual growth we do not start from absolute emptiness but rather from the basis of whatever knowledge, love, faith, and will we have developed at that point in our lives. Thus, the spiritual growth process is lived and dramatized by each individual in a way which is unique to him even though the basic mechanism of progress and the rules which govern it are universal.

5. Tools for Spiritual Growth

Our understanding of the process of spiritual growth and its dynamics does not guarantee that we will be successful in our pursuit of spirituality. We stand in need of practical tools to help us at every turn. The Bahá’í Writings give a clear indication of a number of such tools. In particular, prayer, meditation and study of the Writings of the Manifestations, and active service to mankind are repeatedly mentioned. For example, in a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi it is stated:

When a person becomes a Bahá’í, actually what takes place is that the seed of the spirit starts to grow in the human soul. This seed must be watered by the outpourings of the Holy Spirit. These gifts of the spirit are received through prayer, meditation, study of the Holy Utterances and service to the Cause of God …service in the Cause is like the plough which ploughs the physical soil when seeds are sown.60Excerpt from a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi in The Bahá’í Life, p. 20.

Some of the points mentioned briefly in the above passage are amplified in the following statement from the same source:

How to attain spirituality is indeed a question to which every young man and woman must sooner or later try to find a satisfactory answer.…

Indeed the chief reason for the evils now rampant in society is the lack of spirituality. The materialistic civilization of our age has so much absorbed the energy and interest of mankind that people in general do no longer feel the necessity of raising themselves above the forces and conditions of their daily material existence. There is not sufficient demand for things that we call spiritual to differentiate them from the needs and requirements of our physical existence.…

The universal crisis affecting mankind is, therefore, essentially spiritual in its causes … the core of religious faith is that mystic feeling which unites Man with God. This state of spiritual communion can be brought about and maintained by means of meditation and prayer. And this is the reason why Bahá’u’lláh has so much stressed the importance of worship. … The Bahá’í Faith, like all other Divine Religions, is thus fundamentally mystic in character. Its chief goal is the development of the individual and society, through the acquisition of spiritual virtues and powers. It is the soul of man which has first to be fed. And this spiritual nourishment prayer can best provide.61Excerpt from a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi in Directives from the Guardian (New Delhi: Bahá’í Publishing Trust), pp. 86-87.

With regard to meditation, the Bahá’í Writings explain that it has no set form and each individual is free to meditate in the manner he finds most helpful. Statements by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá describe meditation as a silent contemplation, a sustained mental concentration or focusing of thought:

Bahá’u’lláh says there is a sign (from God) in every phenomenon: the sign of the intellect is contemplation and the sign of contemplation is silence, because it is impossible for a man to do two things at one time—he cannot both speak and meditate. …

Meditation is the key for opening the doors of mysteries. In that state man abstracts himself: in that state man withdraws himself from all outside objects; in that subjective mood he is immersed in the ocean of spiritual life and can unfold the secrets of things-in-themselves.62‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1979), pp. 174-175.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá leaves no doubt concerning the importance of meditation as a tool for spiritual growth:

You cannot apply the name “man” to any being void of this faculty of meditation; without it he would be a mere animal, lower than the beasts. Through the faculty of meditation man attains to eternal life; through it he receives the breath of the Holy Spirit—the bestowal of the Spirit is given in reflection and meditation.63‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1979), p. 175.

And Bahá’u’lláh has said that “One hour’s reflection is preferable to seventy years of pious worship.”64Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-Íqán (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Committee, 1954),p. 238. These strong statements of Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá concerning meditation should not, however, be taken as implying an absolute faith in man’s intuitive powers. See note 39.

The Bahá’í Writings suggest that the words and teachings of the Manifestations provide a helpful focus for meditation. Also, while giving considerable freedom to the individual concerning prayer, they likewise suggest that the prayers of the Manifestations are especially useful in establishing a spiritual connection between the soul of man and the Divine Spirit. Prayer is defined as conversation or communion with God:

The wisdom of prayer is this, that it causes a connection between the servant and the True One, because in that state of prayer man with all his heart and soul turns his face towards His Highness the Almighty, seeking His association and desiring His love and compassion. The greatest happiness for a lover is to converse with his beloved, and the greatest gift for a seeker is to become familiar with the object of his longing. That is why the greatest hope of every soul who is attracted to the kingdom of God is to find an opportunity to entreat and supplicate at the ocean of His utterance, goodness and generosity.65‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Divine Art of Living, p. 27.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá has elsewhere explained that the spirit in which one prays is the most important dimension of prayer. A ritualistic mumbling of words or a mindless repetition of syllables is not prayer. Moreover, the Bahá’í Writings enjoin the spiritual seeker to make of his whole life, including his professional activities, an act of worship:

In the Bahá’í Cause arts, sciences and all crafts are counted as worship. The man who makes a piece of notepaper to the best of his ability, conscientiously, concentrating all his forces on perfecting it, is giving praise to God. Briefly, all effort put forth by man from the fullness of his heart is worship, if it is prompted by the highest motives and the will to do service to humanity. Thus is worship: to serve mankind and to minister to the needs of the people. Service is prayer. …66 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Divine Art of Living, p. 65.

Thus, it is the spirit and motive of service to others which makes external activity a tool for spiritual progress. In order to pursue the goal of spirituality, one must therefore maintain a persistently high level of motivation. Prayer, meditation, and study of the Words of the Manifestations are essential in this regard: