When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited Europe and North America between 1911 and 1913, the West was experiencing a period of great prosperity and peace. Europe had gone almost forty years without a battle on its soil, while the United States had spent nearly half a century healing the wounds of its civil war. The accelerating technological and industrial advances on both sides of the Atlantic were proudly displayed year after year at international expositions visited by citizens and rulers from all corners of the globe. The Western economies had reached unprecedented prosperity, which brought about changes in social organization. It is not surprising, then, that decades later, when describing the gestalt of public opinion in the years preceding the outbreak of World War I, a famous Austrian writer would state: “Never had Europe been stronger, richer, more beautiful, or more confident of an even better future.”1Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday (London: Cassell and Company, 1947), 152.

Such confidence in a peaceful and prosperous future was also supported by rapid changes in international politics. The peace conferences held in The Hague in 1899 and 1907 convinced many statesmen and prominent thinkers that the possibility of war was increasingly remote. For the first time, most of the world’s nations had collectively reached global agreements aimed at preventing war, perhaps the most promising of which was the establishment of an International Court of Arbitration. Experts in international law believed that, through arbitration, countries in conflict could resolve their disputes without resorting to arms or shedding a drop of blood. From 1899 until the outbreak of the Great War, hundreds of arbitration agreements were signed to secure peace between signatory countries. Even Great Britain and Germany signed an agreement in 1904.2For a list of arbitration treaties signed before 1912, see Denis P. Myers, Revised List of Arbitration Treaties (Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1912). Each of these advances was applauded by the many statesmen who were interested in internationalism as a path to peace. The Inter-Parliamentary Union, for example, which brought together more than 3,000 politicians from around the world, supported the court without reservation. Leaders such as President Theodore Roosevelt and his successor, William Taft, supported the court. Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who was president of the New York Peace Society—an organization that had invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to speak to its members—paid for the construction of the Peace Palace in The Hague. The building was inaugurated with great pomp in August 1913, just one year before the outbreak of the Great War.

The conviction that the solution to war lay primarily in international organization was so strong that the Hague Convention of 1907 agreed on the establishment of an International Court of Justice, which would not merely arbitrate but also administer justice and enforce international law. The details of such a court were postponed to a future Hague Conference, planned for the fateful year of 1915.

The academic world also gave credibility, through individuals’ works and studies, to this optimistic vision of the future. Scholars reasoned that a war between world powers would be so costly economically and so devastating militarily that the business world, the banks, the political parties, and public opinion in general would undoubtedly impose reason on any warlike temptation.

“The very development that has taken place in the mechanism of war has rendered war an impracticable operation,” wrote Ivan S. Bloch (1836–1902) in The Future of War. He added, “The dimensions of modern armaments and the organization of society have rendered its prosecution an economic impossibility.”3Ivan S. Bloch, The Future of War (Toronto: William Brigs, 1900), xi. Quoted by Sandi E. Cooper, “European Ideological Movements Behind the Two Hague Conferences (1889–1907)” (PhD. diss., New York University, 1967). This was the sixth volume of Bloch’s Budushchaya voina v tekhnicheskom, ekonomicheskom i politicheskom otnosheniyakh (St. Petersburg: Tipografiya I. A. Efrona, 1898).

Along similar lines, Norman Angell presented psychological and biological arguments in The Great Illusion (1911)—which was translated into more than twenty languages—to show that war would be an exercise in irrationality and suicide for the contending parties.

Optimism also spread to the peace movement, which was not only more influential than it is today but enjoyed far more resources and support. David Starr Jordan, who held a leading position in the World Peace Foundation and was the first president of Stanford University—and who invited ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to speak at Stanford—went so far as to ask in 1913, “What shall we say of the Great War of Europe, ever threatening, ever impending, and which never comes? Humanly speaking, it is impossible. … But accident aside—the Triple Entente lined up against the Triple Alliance—we shall expect no war.”4David Starr Jordan, What Shall we Say? Being Comments on War and Waste (Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1913), 18.

Andrew Carnegie, who had met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá personally and received at least three letters from Him, would speak in similar terms a year before the war: “Has there ever been danger of war between Germany and ourselves, members of the same Teutonic race? Never has it been even imagined … We are all of the same Teutonic blood, and united could insure world peace.”5Andrew Carnegie, “The Baseless Fear of War,” The Advocate of Peace, April 1913, 79–80.

As in other spheres, many in the internationalist movement expressed absolute faith in arbitration as the ultimate means of ending war. “I am able to prove, and this is very essential,” said J. P. Santamaria, an Argentinian representative at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration in the same year that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at the distinguished event (1912), “that the majority of the Latin American republics have already exchanged treaties whereby armed conflicts become practically impossible.”6Report of the annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration (1912), p. 49.

“We believe not only that France, but Germany and Japan as well, would gladly join with England and the United States in treaties of arbitration which would make war forever impossible,” said another of the event’s speakers.7Address of Samuel B. Capen. Report of the annual Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration (1912), p. 159.

Whether as a result of faith in technological progress, hope in the positive influence of international policy aimed at peace, assurance in the power of the economy, or confidence in the supremacy of scientific reason, the prevailing visions for the future of humanity at the time of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to the West were strictly based on material criteria. The outbreak of World War I demonstrated the fallacy of that premise.

‘ABDU’L-BAHÁ’S RADICAL ANALYSIS OF THE CAUSES OF WAR

The diagnosis of the world situation presented by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was very different from that of His contemporaries. Although on numerous occasions He referred to the need to establish international bodies with global reach and sufficient executive power to intervene in conflicts between countries,8For some comments and writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on this issue, see, for example: Makatib-i-Hadrat ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, vol. 4 (Tehran: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 121 B. E.), 161; Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1978) 202:11 and 227:30; Paris Talks (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1967), 40:28; Promulgation of Universal Peace (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2012), 98:10 and 103:11. He also impressed on His audiences the urgent need to focus on the moral causes of war and the spiritual requirements for the establishment of peace.

Far from arguing that war was simply the result of deficient international organization, He asserted that it was also rooted in erroneous conceptions of the human being, which led irremediably towards division and contention. He especially warned of the dangers of racism and nationalism, which define the individual according to material parameters—bodily appearance and community of birth, respectively—and prioritize human beings and entire societies according to these factors, thus generating inequality and injustice, and fostering hatred and alienation, among human groups. He also referred to religious hatred, which He described as contrary not only to the foundation of religions but also to divine will.

“All prejudices, whether of religion, race, politics or nation, must be renounced, for these prejudices have caused the world’s sickness,” He said in a talk in Paris in 1911. Prejudice, He asserted, is “a grave malady which, unless arrested, is capable of causing the destruction of the whole human race. Every ruinous war, with its terrible bloodshed and misery, has been caused by one or other of these prejudices.”9‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 45:1. Ibid., p. 159.

“Man has laid the foundation of prejudice, hatred and discord with his fellowman,” He explained in 1912 in a speech at a Brooklyn church, “by considering nationalities separate in importance and races different in rights and privileges.”10‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 82:11.

“As long as these prejudices prevail, the world of humanity will not have rest,” He wrote years later.11‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 227:10. This is part of one of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s communications to the Central Organization for a Durable Peace, in The Hague.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá rejected the premises on which each of these models of thought were based. He denied, for example, the objective existence of races, stating instead that “humanity is one kind, one race and progeny, inhabiting the same globe.”12‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “Address to the International Peace Forum, New York, 12 May 1912,” Promulgation of Universal Peace, 47:6. He also denied that nations are natural realities, referring to national divisions as “imaginary lines and boundaries.”13‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 98:6. He denied any essential differences between religions, since they all have a common origin, share the same spiritual foundations, and are essentially one and the same. Furthermore, He affirmed that religious differences are due to “dogmatic interpretation and blind imitations which are at variance with the foundations established by the Prophets of God,”14‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 110:15. stressed that these aspects of religion must disappear, and even went so far as to declare that “if religion be the cause of enmity surely the lack of religion is better than its presence.”15“Abdul Baha Gives His Impressions of New York”, The Sun (New York), 7 July 1912, 8.

He spoke at a time when the ideologies characteristic of a culture of inequality (racism, nationalism, sexism, and so on) were on the rise, gradually pushing humanity into what would be the bloodiest and most catastrophic century of its history. Racism, for example, was endorsed by a significant portion of the scientific community of the time and was firmly established in large parts of the world in the form of discriminatory and segregationist laws. It was even undergoing a major transformation equipped by new “scientific” techniques—such as craniometry, phrenology, and physiognomy—that inspired new and abhorrent “social reform” initiatives, such as eugenics and racial hygiene. Nationalism, for the first time in history, had instilled in the majority of humanity the vision of a globe divided into parcels of land defined by races, cultures, and languages. It drove imperialist and colonialist policies, while colonialism, in turn, exported nationalism, imposing previously nonexistent categories and definitions on citizens and territories worldwide. At the same time, longstanding religious conflicts were still very much present, reviving old grievances and warlike moods—as exemplified by the chronic problems in the Balkans, which were in full swing when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá visited the West.

Even individuals and organizations with noble goals held such doctrines of inequality. Many pacifists, for example, saw war not so much as a moral problem, but as a biological one. Influenced by racism and social Darwinism, they based their criticism of war on the argument that “fit” men were sent to the battlefield, where they died, while “unfit” men stayed behind and reproduced. The consequence of such a phenomenon, they believed, was “racial weakening.”

“Only the man who survives is followed by his kind,” wrote the aforementioned David Starr Jordan. “The man who is left determines the future. From him springs the ‘human harvest’ …”16David Starr Jordan, War’s Aftermath (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), xv.

Along the same lines, Norman Angell also criticized colonial expansion in biological terms, arguing that domination and contact between civilizations prolonged the life of “weak races.”

“When we ‘overcome’ the servile races,” Angell reasoned in his internationally best-selling book, “far from eliminating them, we give them added chances of life by introducing order, etc., so that the lower human quality tends to be perpetuated by conquest by the higher. If ever it happens that the Asiatic races challenge the white in the industrial or military field, it will be in large part thanks to the work of race conservation, which has been the result of England’s conquest …”17Norman Angell, The great illusion (London: William Heinemann, 1910), 189. In 1933 Angell would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Benjamin Trueblood, secretary of the American Peace Society, who met ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Washington, D.C., raised the possibility of a future world federation as a consequence of a “great racial federation” in the Anglo-Saxon world.18Benjamin Trueblood, The Federation of the World (Boston: The Riverside Press, 1899), 132. This idea was similar to that put forward by Andrew Carnegie.

In this context, we can understand—with the perspective provided by the passage of more than a century since His travels—that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s warnings about the causes of war could not be understood by societies immersed in paradigms of thought totally different from the ones He presented.

And just as the meanings and diagnoses of the causes of war differed between those provided by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the dominant discourses of the time, so did proposals for the establishment of peace. As explained, the international community had placed its hope in legislation and international institutions as mechanisms for ensuring peace; some pacifists sincerely believed that such changes also required the racial hegemony of certain peoples. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, however, emphasized a completely different concept: peacemaking would only be possible when humanity reached the understanding that it is one and acted in accordance with this principle. He brought this idea forward in a great number of His talks. For instance, in Minneapolis, He stated that human beings “must admit and acknowledge the oneness of the world of humanity. By this means the attainment of true fellowship among mankind is assured, and the alienation of races and individuals is prevented … In proportion to the acknowledgment of the oneness and solidarity of mankind, fellowship is possible, misunderstandings will be removed and reality become apparent.”19‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 105:6.

By making such a statement, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá presented His listeners with a radical challenge. The recognition of the oneness of the human race implies, on one hand, the acceptance that there is a primordial identity common to all human beings, which goes beyond any physical or accidental diversity between individuals. It also implies the abandonment of any vision of the human being—foundational to beliefs such as racism, sexism, unbridled nationalism, and religious exclusivism—that justifies human inequality. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s approach, therefore, clashed head-on with the discourses of the time and the materialistic premises that underpinned them.

THE GREAT WAR

Although ‘Abdu’l-Bahá praised on numerous occasions progress that humanity was experiencing, for example in economics, politics, science, and industry, He also warned that material progress alone would not be capable of bringing true prosperity without a commensurate spiritual advancement.

“Material civilization concerns the world of matter or bodies,” He explained during His visit to Sacramento, “but divine civilization is the realm of ethics and moralities. Until the moral degree of the nations is advanced and human virtues attain a lofty level, happiness for mankind is impossible.”20‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 113:15.

From this perspective, the ideologies of inequality that permeated all areas of human endeavor were totally incapable of promoting lasting peace, including in movements that promoted pacifism, internationalism, and diplomacy.

“The Most Great Peace cannot be assured through racial force and effort,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained in an address in Pittsburgh:

It cannot be established by patriotic devotion and sacrifice; for nations differ widely and local patriotism has limitations. Furthermore, it is evident that political power and diplomatic ability are not conducive to universal agreement, for the interests of governments are varied and selfish; nor will international harmony and reconciliation be an outcome of human opinions concentrated upon it, for opinions are faulty and intrinsically diverse. Universal peace is an impossibility through human and material agencies; it must be through spiritual power …

For example, consider the material progress of man in the last decade. Schools and colleges, hospitals, philanthropic institutions, scientific academies and temples of philosophy have been founded, but hand in hand with these evidences of development, the invention and production of means and weapons for human destruction have correspondingly increased …

If the moral precepts and foundations of divine civilization become united with the material advancement of man, there is no doubt that the happiness of the human world will be attained and that from every direction the glad tidings of peace upon earth will be announced.21‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 44:13–15.

Based on this premise, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá challenged a falsely optimistic vision of the world, noting that, if the moral and spiritual dimensions of social reality were also assessed, it would become apparent that the world was experiencing a moment of great decadence. “If the world should remain as it is today,” He said in Chicago in 1912, “great danger will face it.”22‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 104:1.

“Observe how darkness has overspread the world,” he explained in Denver:

In every corner of the earth there is strife, discord and warfare of some kind. Mankind is submerged in the sea of materialism and occupied with the affairs of this world. They have no thought beyond earthly possessions and manifest no desire save the passions of this fleeting, mortal existence. Their utmost purpose is the attainment of material livelihood, physical comforts and worldly enjoyments such as constitute the happiness of the animal world rather than the world of man.23‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Promulgation of Universal Peace, 107:4.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá warned of the acute risk of an impending international conflict on no less than seventeen occasions. “Europe itself,” He said in Paris in 1911, “has become like one immense arsenal, full of explosives, and may God prevent its ignition—for, should this happen, the whole world would be involved.”24“Apostle of Peace Here Predicts an Appalling War in the Old World,” The Montreal Daily Star, 31 August 1912, 1. [The following includes numerous incomplete citations—most need page or publisher data] For other comments about the possibility of a war, see Promulgation of Universal Peace, 3:7, 103:11, 108:1, 114:2; ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on Divine Philosophy (Boston: The Tudor Press, 1918), 95. “The Awakening of Older Nations,” The Advertiser (Montgomery, Alabama), 7 May 1911; “Turks Prisoner for 40 Years,” The Daily Chronicle (London), Western Edition, 17 January 1913, 1; “Abdul Baha’s Word to Canada,” Toronto Weekly Star, 11 September 1912; Montreal Daily Star, 11 September 1912, 2; “Abdul Baha’s Word to Canada,” Montreal Daily Star, 11 September 1912, 12; “Persian Peace Apostle Predicts War in Europe,” Buffalo Courier, 11 September 1912, 7; “Message of Love Conveyed by Baha,” Buffalo Enquirer, 11 September 1912, 5; “Urges America to Spread Peace,” Buffalo Commercial, 11 September 1912, 14; “Abdul Baha an Optimist,” Buffalo Express, 11 September 1912, 1; “Bahian Prophet Returns After a Trip to Coast,” Denver Post, 29 October 1912, 7.

Despite this and other explicit warnings, His audiences remained for the most part unmoved. Confidence in material well-being weighed more heavily on public opinion than His diagnosis of the moral state of the world.25‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks, 34:5.

He reiterated his warnings in the years between the end of World War I and His passing in 1921. In His correspondence, He explained that a second world conflagration was imminent, despite the terror caused by the first world war and the enormous progress that had been made in international governance with the establishment of the League of Nations.

“Although the representatives of various governments are assembled in Paris in order to lay the foundations of Universal Peace and thus bestow rest and comfort upon the world of humanity,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote in 1919, “yet misunderstanding among some individuals is still predominant and self-interest still prevails. In such an atmosphere, Universal Peace will not be practicable, nay rather, fresh difficulties will arise.”26‘Abdu’l-Bahá, tablet to David Buchanan of Portland, Oregon, Star of the West, 28 April 1919, 42.

“For in the future another war, fiercer than the last, will assuredly break out,” He wrote in 1920. “Verily, of this there is no doubt whatever.”27Letter to Ahmad Yazdaní, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 228:2.

In another letter sent the same year, He was even more explicit. After presenting—as He had done in His addresses in the West—some of the spiritual requirements for the establishment of peace, He closed by enumerating some of the elements that would eventually lead humanity to World War II just nineteen years later:

The Balkans will remain discontented. Its restlessness will increase. The vanquished Powers will continue to agitate. They will resort to every measure that may rekindle the flame of war. Movements, newly born and worldwide in their range, will exert their utmost effort for the advancement of their designs. The Movement of the Left will acquire great importance. Its influence will spread.28Letter sent through Martha Root, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 202:14.

THE BIRTH OF A NEW SOCIETY

No reader of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá should be tempted to think that, in His exposition of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, He moved only within the theoretical realm. On the contrary, while His efforts to spread Bahá’u’lláh’s message were enormous, His endeavors to bring those teachings into the realm of action were colossal. In a conversation in London, for example, referring to one of the many congresses held at the time, bringing together philanthropists eager to improve the world, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stressed, “To know that it is possible to reach a state of perfection, is good; to march forward on the path is better. We know that to help the poor and to be merciful is good and pleases God, but knowledge alone does not feed the starving man …”29‘Abdu’l-Bahá in London (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982)60.

Throughout His ministry, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá directed the Bahá’í community to make itself a model of the future society foretold by Bahá’u’lláh—one through which humanity might witness the transformations that accompany the application of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings to social and interpersonal relations.

In several of His talks, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá described the Bahá’ís of Persia (now Iran) as one such example. They lived in an environment in which religious segregation was a social reality. Zoroastrians, Jews, Christians, and other religious minorities lived in isolation from their Muslim neighbors and also separated from each other. Being considered impure beings (najis), the minority groups were subject to strict rules that regulated not only their relations with Muslims, but also the jobs they performed and even the clothes they wore. In this environment, bringing people from different religious backgrounds together in the same room was not just taboo, but unthinkable. Despite this, the Bahá’í community in Persia managed to become—first under the guidance of Bahá’u’lláh and then of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá—a cohesive group comprising people from all religious backgrounds. Having in common their faith in the transformative capacity of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings, they were able to set aside prejudices inherited from the surrounding society and their ancestors and work together to improve conditions for their fellow citizens. It was not long before Persian Bahá’ís—men and women alike—learned to make decisions collectively and to implement them without regard for different backgrounds or genders.

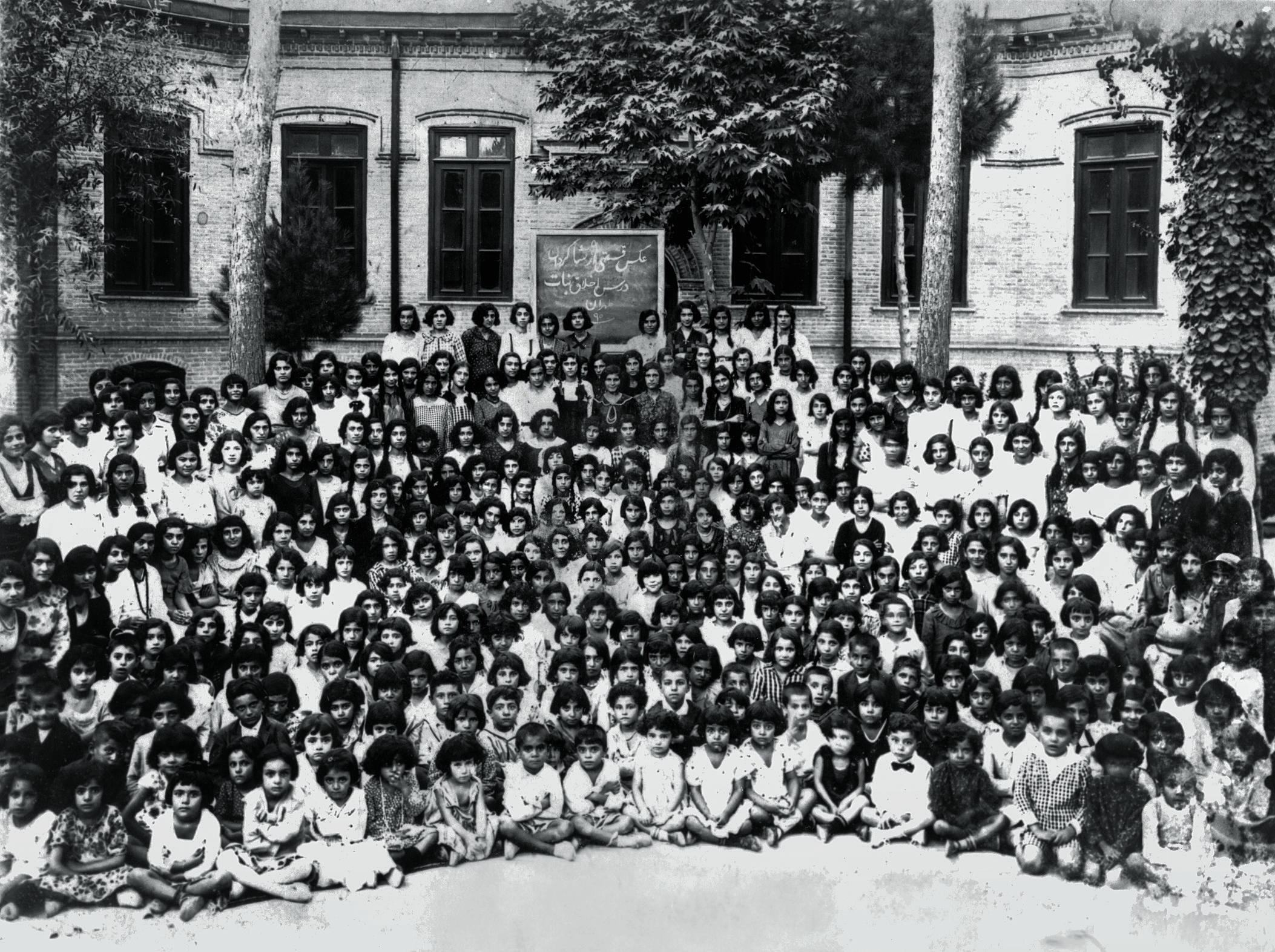

Such a change not only resulted in the unprecedented growth of the Bahá’í community, but also in the proliferation of numerous social and charitable projects throughout the country. For example, during the ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the Persian Bahá’ís managed to establish no less than twenty-five schools, including some of the country’s first schools for girls. Beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century, Bahá’ís in Persia also established health centers in several cities, including the Sahhat Hospital in Tehran, which followed the instructions of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to include in its mission statement that it would provide “service to mankind, regardless of race, religion and nationality,” a revolutionary statement at that time and place.30Seena B. Fazel and Minou Foadi. “Baha’i health initiatives in Iran: a preliminary survey,” The Baha’is of Iran, eds. Dominic P. Brookshaw and Seena B. Fazel (New York: Routledge, 2008), 128.

While this was happening in the East, American Bahá’ís were working under the leadership of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to racially integrate their community.

“Strive with heart and soul in order to bring about union and harmony among the white and the black and prove thereby the unity of the Bahá’í world wherein distinction of color findeth no place, but where hearts only are considered,” He wrote in one of His letters to them. “Variations of color, of land and of race are of no importance in the Bahá’í Faith; on the contrary, Bahá’í unity overcometh them all and doeth away with all these fancies and imaginations.”31Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 75.

He also exhorted them to “endeavor that the black and the white may gather in one meeting place, and with the utmost love, fraternally associate with each other.”32Bonnie J. Taylor and National Race Unity Conference, eds., The Power of Unity (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1986), 30.

“If it be possible,” He wrote on another occasion, “gather together these two races—black and white—into one Assembly, and create such a love in the hearts that they shall not only unite, but blend into one reality. Know thou of a certainty that as a result differences and disputes between black and white will be totally abolished.”33The Power of Unity, 28.

The process by which the Bahá’í community in the United States became a model of racial integration was accelerated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to North America—through His personal example, His participation in integrated meetings, His encouragement to Bahá’ís who held them, and His constant instructions in all the cities He visited on the issue of race.

After the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá commissioned Agnes Parsons, a Bahá’í and member of high society in Washington, D.C., to organize the first Race Amity Conference, which took place in May 1921. The event, promoting racial unity and harmony, triggered a national movement that replicated the Conference in different parts of the United States in the following years, involving not only the American Bahá’í community, but also many other organizations and societal leaders. The result of these efforts was the transformation of the Bahá’í community into a group actively engaged in banishing the racial prejudices so present in its surrounding society.

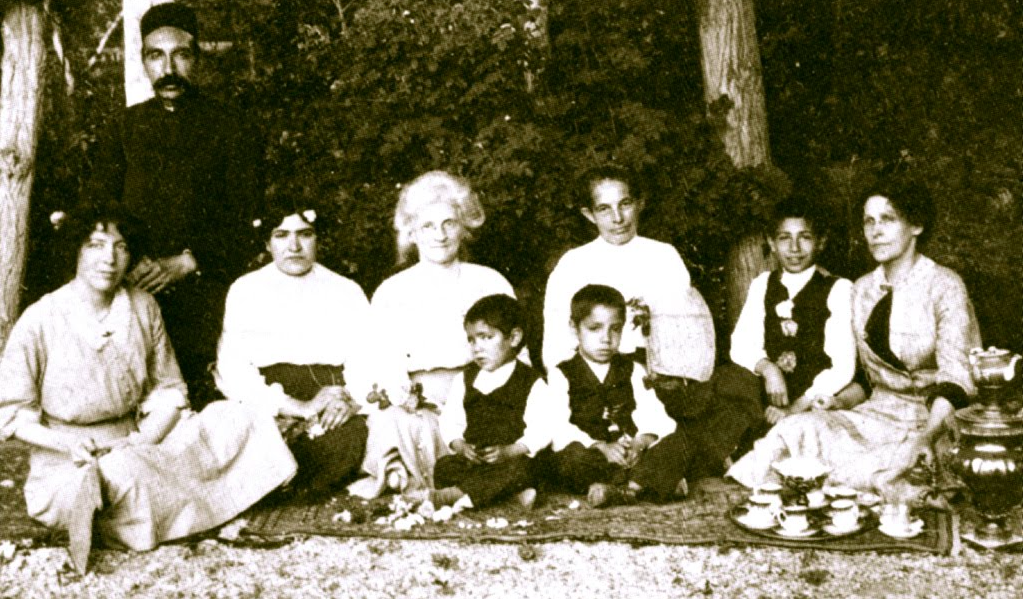

In His efforts to demonstrate, through the global Bahá’í community, empirical proof that unity and freedom from prejudice leads to peace, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also promoted collaborative ties between the Bahá’ís of the West and the East. Beginning in the early twentieth century, He encouraged Persian Bahá’ís to travel to Europe and North America, and Western Bahá’ís to visit Persia or India. He promoted communications between Bahá’í communities. For example, the Star of the West, the journal of the Bahá’ís of the United States, included a section in Persian and was regularly sent to Persia. As development projects in Persia grew and became more complex, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged Western Bahá’ís to support them and extend assistance. As a result, in 1909, Susan Moody, M.D., moved to the country to work at the Sahhat hospital in Tehran. Moody was followed by other Bahá’ís, including teacher and school administrator Lilian Kappes, nurse Elizabeth Stewart, and fellow doctor Sarah Clock. In 1910, the Orient-Occident Unity was founded with the aim of establishing collaboration in different fields between the people of Persia and the United States.34This name was adopted in 1912. Its earliest name was the Persian-American Educational Society. The work of this organization involved not only many Bahá’ís, but other prominent organizations and individuals.

All these transformations provided glimpses of the social implications of the principles promulgated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and presented examples of the effects generated by applying in the field of action the principle of world unity and the conception of the human being enunciated by Bahá’u’lláh.

ADDRESSING THE IMMEDIATE NEEDS

On 24 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austrian-Hungarian Empire, was assassinated in Sarajevo. A few weeks later, the European powers were at war, and the disaster predicted by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá only a few years earlier became a reality.

The Ottoman regions of Syria and Palestine did not escape the dire consequences of the conflagration. The area was hit by famine caused by pillaging Ottoman troops as they crossed the territory to reach Egypt, where they were defending the strategic Suez channel. In the Haifa area, circumstances were particularly complicated. The local population held diverging alliances. The Arabs were divided between those sympathizing with the French and those supporting the Ottoman Empire, while the members of the large German colony supported their own country. These divisions caused tension and sometimes produced violence. The city was also the target of bombings from the sea. Thus, within a few weeks, Haifa and its surroundings experienced a rapid transition from a relative state of peace to severe insecurity associated with a humanitarian crisis. The conflict caused acute needs that required urgent attention.

Before the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had taken steps that would allow Him to ameliorate these conditions. His most visible contribution was to provide food for the people of Haifa and its vicinity. At the beginning of the twentieth century, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had established various agricultural communities around the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan Valley, with the most important one in ‘Adasiyyih, in present-day Jordan. During the hardest years of the war, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent shipments of foodstuffs from this location to Haifa, using some two hundred camels for just one trip, which gives an idea of the scale of the aid.35For more information on this, see Iraj Poostchi, “Adasiyyah: A Study in Agriculture and Rural Development,” Bahá’í Studies Review 16 (2010), 61–105. To distribute the food within the population, He organized a sophisticated rationing system using vouchers and receipts to ensure that the food reached all those in need while preventing abuse.

“He was ever ready to help the distressed and the needy,” a witness was quoted as saying in 1919 in London’s Christian Commonwealth:

… often He would deprive himself and his own family of the necessities of life, that the hungry might be fed and the naked be clothed. … For three years he spent months in Tiberias and Adassayah, supervising extensive works of agriculture, and procuring wheat, corn and other food stuffs for our maintenance, and to distribute among the starving Mohamedan and Christian families. Were it not for his pre-vision and ceaseless activity none of us would have survived. For two years all the harvests were eaten by armies of locusts. At times like dark clouds they covered the sky for hours. This, coupled with the unprecedented extortions and looting of the Turkish officials and the extensive buying of foodstuffs by the Germans to be shipped to the “Fatherland” in a time of scarcity, brought famine. In Lebanon alone more than 100.000 people died from starvation.36“News of Abdul Baha,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 22 January 1919, 196. Text in Amín Egea, The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2 (Oxford: George Ronald, 2018), 427–428.

“Abdul Baha is a great consolation and help to all these poor, frightened, helpless people,” another report read.37“Bahai News,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 3 March 1915, 283. Text in The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2, 410.

A few years later—just after the war—a British army officer described ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s role in reuniting the divided peoples of Haifa, saying, “Many are looking to him to solve the problems arising between Moslem and Christian sects.”38W. Tudor Pole, quoted in “Palestine of Tomorrow,” Christian Commonwealth (London), 24 September 1919, 614. Text in The Apostle of Peace, vol. 2, 426.

READING REALITY IN TIMES OF CRISIS

The three levels of action taken by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on the issue of war—participation in the discourses of His time, building a community based on spiritual principles, and paying attention to the immediate needs arising from the outbreak of war—offer us an opportunity to reflect, nearly one hundred years after His passing, on the appropriateness of the models of thought that currently influence global decision-making.

Today, as then, the world is beset by a large number of threats. The progressive environmental decline, the deficient global economic system—which allows for the existence of extremes of wealth and poverty and, at the same time, periodically causes major economic crises—the prevalence of war in a multitude of forms and its constant threat in a context of unprecedented technological development, the rapid spread and assimilation of hate mongering of all kinds and of all orientations, and the rise of an unfettered nationalism with an associated drive against human diversity and resistance to the processes of global convergence, are just some of the challenges facing humanity. In addition to these, which have been created by human beings themselves, there are others of an unexpected and natural character which, like the current global pandemic, highlight the fragility of a human ecosystem that has been greatly weakened by internal divisions and inequalities.

If the response to these crises—some of them unprecedented—is to be based on contradictions similar to those of the internationalists or pacifists of the years before the Great War, we can anticipate that any remedy applied will be dramatically limited in its influence. Can, for instance, a humanity that still clings to a nationalistic world view provide an adequate response to global problems? Is it possible for societies that perceive consumerism and the accumulation of goods as a path to true happiness to find solutions to crises such as global warming?

If we heed ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s advice, the diagnosis of these and future crises should not depend solely on an analysis of the material circumstances that converge in each of them, but should also address the ultimate, moral causes of these phenomena. Some of these include the pursuit of self-interest, submission to materialism, the perception that struggle and strife are legitimate means of resolving conflicts, the persistence of prejudices that deny human equality, and the distortion of the purpose of religion. As ‘Abdu’l-Bahá consistently stated in His talks and writings, the solutions to the problems that afflict the human race depend not only on a change in the material conditions of humanity but also on a transformation in our understanding of what it means to be human, of our existential purpose, and of the moral framework upon which we base our actions.