By 1914, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was well known in many parts of the globe for His life of service to humanity. In the Holy Land, where He had lived most of His adult life, He was revered for His service to the poor and needy in the community and for His engagement in the discourses of the day with local and regional dignitaries. His lengthy sojourns in Egypt before and after His historic visits to Europe and North America also attracted considerable attention, earning Him even more admirers from all walks of life. His travels in the West, from which He had only recently returned in early 1914, have been particularly well-documented; in both formal and informal settings and to diverse audiences, His explications of the Teachings of His Father, Bahá’u’lláh, in the context of the urgent promotion of global peace, made Him a unique Figure on the world stage. In the war years, He would win widespread acclaim for helping to avert a famine in His home region of Haifa and ‘Akká. And for many around the world, the example of His life and His voluminous Writings were and continue to be sources of guidance and elucidation.

However, rather less well known today is ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s sustained promotion of modern education in the Middle East. Perhaps most striking in this regard is how, over a period of several years, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged and nurtured a group of Bahá’í students in Beirut to pursue higher education in a way that was coherent with the students’ identities as Bahá’ís.

Among ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s many visitors in early 1914 was Howard Bliss, the president of the Syrian Protestant College (SPC), an institution with which ʻAbdu’l-Bahá had maintained a longstanding relationship and at which a group of Bahá’í students had become an established presence by the time of Bliss’s visit that February.1H.M Balyuzi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh (Oxford: George Ronald, 1973), 405. Bliss, an American who had grown up on the campus of the college in Beirut (his father, Daniel Bliss, was the college’s first president) and who spoke fluent Arabic, was visiting, in part, to arrange for the Bahá’í students to spend their upcoming spring break in Haifa in the vicinity of the Shrines of Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb, affording them an opportunity to meet and learn from ʻAbdu’l-Bahá. But the conversation between ʻAbdu’l-Bahá and Bliss extended to topics of pressing concern for the former. Much as He had done on numerous occasions during His travels, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá encouraged Bliss to foster in his students “principles” such as the “oneness of the world of humanity,” among others, so that their education could be directed toward “universal peace.”2Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98, http://sotwbnewsinfo.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/sotw/searchable_pdfs/SotW_Vol-01%20(Mar%201910)-Vol-10%20(Mar%201919).pdf See also “Zeine on Modern Education,” Al-Kulliyah, Winter 1973, 15, American University of Beirut/Library Archives.

Bliss’s receptivity to ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s remarks and encouragement was evident in a speech Bliss gave just ten days later. On 25 February, in a meeting with a group of students that was representative of the school’s rich diversity, Bliss urged it to include the “establishing of universal peace” as one of its “missions.”3Al-Kulliyah, March 1914, No. 5, 151, American University of Beirut/Library Archives ʻAbdu’l-Bahá and Bliss’s exchange, indeed, was emblematic of the larger conversation the Bahá’í community and the college had been having for several years, a conversation centering on the college’s self-styled “experiment in religious association” to which the Bahá’í students had been striving to contribute.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá and Modern Education

The Syrian Protestant College was founded in 1866 and formally renamed the American University of Beirut (AUB) in 1920. Long before any Bahá’í students had enrolled there, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in an 1875 treatise known today as The Secret of Divine Civilization4Available at www.bahai.org/r/093729958 encouraged the establishing of modern schools in His native Persia, advocating for the “extension of education, the development of useful arts and sciences, the promotion of industry and technology.” 5‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Secret of Divine Civilization. Available at www.bahai.org/r/568414401 Education, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá asserted, should uplift individuals for the ultimate purpose of benefiting society. Over the following decades, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was instrumental in the establishment of dozens of schools throughout His native land; notably, these schools, including many for girls, welcomed students of all faiths.6See Soli Shahvar, The Forgotten Schools: The Baha’is and Modern Education in Iran, 1899-1934 (London: Taurus Academic Studies, 2009).

‘Abdu’l-Bahá personally supervised such initiatives in His local community in ‘Akká as well. In 1903, for example, about twenty children from the Bahá’í community were assembled for classes in English, Persian, math, and other subjects including practical instruction in trades like carpentry, shoemaking, and tailoring.7Youness Afroukhteh, Memories of Nine Years in ‘Akká, Trans. by Riaz Masrour (Oxford: George Ronald, 2003), 159-60. Many of these students continued their studies at local schools, such as a French one in Haifa.8Riaz Khadem, Shoghi Effendi in Oxford and Earlier (Oxford: George Ronald, 1999), 2. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá encouraged students such as these, including His own grandchildren, to continue their education at colleges and universities, the closest of which was SPC; Shoghi Effendi, His eldest grandson and successor as Head of the Bahá’í Faith, graduated from SPC in 1917.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá repeatedly qualified his support of such schools with the condition that they attend to the whole student and produce graduates who had progressed not only scientifically but also morally. During his visit to North America in 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke at Columbia and Stanford universities, praising the value of the scientific education they provided while also emphasizing the necessity of “spiritual development…the most important principle [of which] is the oneness of the world of humanity, the unity of mankind, the bond conjoining East and West, the tie of love which blends human hearts.”9‘Abdu’l-Bahá. The Promulgation of Universal Peace: Talks Delivered by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá during His Visit to the United States and Canada in 1912. Available at www.bahai.org/r/650712298

By this time, Bahá’í students from Haifa and ‘Akká, as well as Persia, Egypt, and Beirut, had attended SPC for about a decade, in increasing numbers over the previous few years. There were no comparable institutions in their own countries, and attending universities in Europe or America was not yet practical for most. As SPC became a popular choice, the prospect of joining an existing group of Bahá’í students was an additional attraction. A sizable group of students as well attended the Université Saint-Joseph (USJ), also in Beirut. Together, they constituted a single coherent group, meeting together, visiting each other, and collaborating, for example, in the activities of the “Society of the Bahá’í Students of Beirut,” which was formed in 1906.10Zeine N. Zeine, “The Program of the Society of Bahá’í Students of Beirut 1929-1930” (unpublished report, n.d.) ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Himself visited SPC during at least one of his visits to Beirut in 1880 and 1887.11Necati Alkan, “Midhat Pasha and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in ‘Akka: the Historical Background of the Tablet of the Land of Bā,” Baha’i Studies Review 13 (2005): 6-7, https://bahai-library.com/pdf/a/alkan_midhat_pasha_abdulbaha.pdf

The Bahá’í students’ engagement with educational institutions like SPC was very much framed in the terms ʻAbdu’l-Bahá had been setting forth for many years, perspectives inspired by the Teachings of His Father, Bahá’u’lláh. One such Teaching was the harmony of science and religion; as noted, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was calling for education to attend to the building of character as well as the shaping of intellects. This was a matter of intense interest at the college as well. While colleges in America had moved away from direct religious instruction, at SPC, there was still an effort to provide it.12Betty S. Anderson, The American University of Beirut: Arab Nationalism and Liberal Education (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 38. Around the time of ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s first visit, the faculty and missionaries associated with SPC had become sharply divided over just how to reconcile this religious education with the school’s scientific training. This rift had only deepened over the decades even as the younger Bliss had taken the college in increasingly “secular,” or liberal, directions. By 1908, the college’s course catalogue framed its approach in decidedly liberal terms, asserting that the “primary aim” of the curriculum is to “to develop the reasoning faculties of the mind, to lay the foundations of a thorough intellectual training, to free the mind for independent thought.”13Anderson, American University of Beirut, 52. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was supportive of the college’s efforts in this regard. As He Himself recorded in conversation with other visitors a week after Bliss’s visit:

The American College at Beirut is carrying on a sacred mission of education and enlightenment and every lover of higher culture and civilization must wish it a great success…Years ago I went to Beirut, and visited the College in its infancy. From that time on I have praised the liberalism of this institution whenever I found an opportunity.14Earl Redman. Visiting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Vol. 2: The Final Years, 1913-1921 (Oxford: George Ronald, 2021), 24-5.

Yet Bliss and others were intent on maintaining the Christian identity of the college. Heavily influenced by the Social Gospel and Progressive movements, Bliss’s conception of religious education “melded religion, character, and social service”15Anderson, American University of Beirut, 67. and, in his words, sought to “set so high, so noble, so broad, so ecumenical a type of Christianity before our students” as to inspire their education and future services to society.16Anderson, American University of Beirut, 64.

Howard Bliss presumably had this project in mind when, on 15 February 1914, he asked ʻAbdu’l-Bahá for His thoughts on “ideal” education.17“Zeine,” Al-Kulliyah, 15. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s response set forth “three cardinal principles.” These principles affirm the need for unfettered intellectual inquiry in education; however, they also call for the moral and ethical development of students and their reorientation toward a broadly conceived mission of service to humanity. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s comments were as follows:

In this age the college which is dominated by a denominational spirit is an anomaly, and is engaged in a losing fight. It cannot long withstand the victorious forces of liberalism in education. The universities and colleges of the world must hold fast to three cardinal principles.

First: Whole-hearted service to the cause of education, the unfolding of the mysteries of nature, the extension of the boundaries of pure science, the elimination of the causes of ignorance and social evils, a standard universal system of instruction, and the diffusion of the lights of knowledge and reality.

Second: Service to the cause of morality, raising the moral tone of the students, inspiring them with the sublimest ideals of ethical refinement, teaching them altruism, inculcating in their lives the beauty of holiness and the excellency of virtue and animating them with the excellences and perfections of the religion of God.

Third: Service to the oneness of the world of humanity; so that each student may consciously realize that he is a brother to all mankind, irrespective of religion or race. The thoughts of universal peace must be instilled into the minds of all scholars, in order that they may become the armies of peace, the real servants of the body politic – the world. God is the Father of all. Mankind are His children. This globe is one home. Nations are the members of one family. The mothers in their homes, the teachers in the schools, the professors in the college, the presidents in the universities, must teach these ideals to the young from the cradle up to the age of manhood.18Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s vision for education, as expressed above, included an implicit repudiation of social Darwinism, a theory which in the decades between His visit to SPC and His 1914 meeting with its college president had become increasingly popular. Ironically, while conservative thinkers initially rejected Darwin’s scientific theory of evolution, they later embraced its implications for society, when they associated a certain conception of progress as connected with “dominant” races and civilizations, that is, white and European ones.19Norbert Scholz, “Foreign Education and Indigenous Reaction in Late Ottoman Lebanon: Students and Teachers at the Syrian Protestant College” (PhD diss., Georgetown University, 1997), 233. The more liberal wing at the college also conflated its approach to Protestant education with “Americanism.”20Anderson, American University of Beirut, 57. As one commentator has put it, the college was sending the message that only “America and Protestantism had the tools for this progressive future.”21Anderson, American University of Beirut, 89.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá, however, urged Bliss to encourage his students to see themselves as serving the higher interests of humanity, not the particular ones of race or nation. In October of 1912, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá had implored assembled students, faculty, and staff at Stanford University along much the same lines, explaining that “the law of the survival of the fittest” did not apply to humanity.22‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/055943431 Acceding to such a law would be similar to allowing nature to remain uncultivated and unfruitful. Human progress, then, required education in the “ideal virtues of Divinity,” for humanity is inherently “lofty and noble” and “specialized” to “render service in the cause of human uplift and betterment.”23‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/935144964

Responding to a Crisis at the College

At the time of Bliss’s visit, a major controversy was raging at the college: the question of mandatory attendance at the school’s religious services. The college’s religious requirements had relaxed over the years and, partly as a result, the school had begun to attract a more diverse student body, not only Christians from various denominations but also more Muslims, Jews, Druze, and Bahá’ís. Spurred on by the Young Turk revolution of 1908 which, among others, advocated for religious freedom and equality, in early 1909, the majority of the Muslim students refused to attend Christian religion services and Bible classes, presenting a petition to the faculty a few days later requesting that such attendance become voluntary.24Stephen B. L Penrose, That They May Have Life: The Story of the American University of Beirut 1866-1941. (Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1970; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1941) 134-35. In addition to widespread opposition from Jewish students as well, the college also faced opposition from the local Muslim community, the Ottoman authorities, and American diplomats. While making some concessions to the striking students, the college largely withstood the pressure, and the mandate remained until 1915, when an Ottoman law made attendance voluntary. Bliss’s 1914 visit, in fact, was part of a tour of the region in which Bliss engaged with a number of civil and religious leaders in order to defend the college’s approach to religious education.

It was in this particular context that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s comments to Bliss about the “cardinal principles” of education were made. While it was clear to many, including ʻAbdu’l-Bahá, that missionary institutions like SPC were in a “losing fight” and the forces of liberalism were in the ascendant, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was unstinting in His support of religious education of a certain type, an education in “service to the cause of morality” and “animating [students] with the excellences and perfections of the religion of God.” As He had explained a year and a half before at Stanford:

Fifty years ago Bahá’u’lláh declared the necessity of peace among the nations and the reality of reconciliation between the religions of the world. He announced that the fundamental basis of all religion is one, that the essence of religion is human fellowship and that the differences in belief which exist are due to dogmatic interpretation and blind imitations which are at variance with the foundations established by the Prophets of God.25‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/819122974

For ʻAbdu’l-Bahá, religion was one, and it was indispensable to the success of any educational enterprise if it encouraged love and unity. However, as He repeatedly made clear, “if religious belief proves to be the cause of discord and dissension, its absence would be preferable.”26‘Abdu’l-Bahá. Promulgation. Available at www.bahai.org/r/819122974 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision for religious education, then, was unifying but also demanding; such education had to generate higher levels of unity than that previously attained.

Responding to the well-documented protests of those in the Muslim community, including many reformers, who thought the religious services would have a negative effect on the students, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá remarked, “I am sure the morals of the students will not be corrupted. They will be informed with the contents of the Old and New Testament. What harm is there in this? A church is house of prayer. Let them enter therein and worship God. What wrong is there in this?”27Redman, Visiting, 25. Indeed, He viewed such attendance as a potential benefit to all concerned:

I have no doubt that much good will be accomplished, and many misunderstandings will be removed, if the [Muslims] attend the Churches of the Christians with reverence in their hearts and sincerity in their souls, and likewise the Christians may go [to] Mohammedan Mosques and magnify the Creator of the Universe. Is it not revealed in the Holy Scriptures that ‘My House shall be called of all nations the House of Prayer? All the houses of different names, — Church, Mosque, Synagogue, Pagoda, Temple are no other than the House of Prayers. What is there in a name? Man must attach his heart to God and not to a building. He must love to hear the name of God, no matter from what lips…28Redman, Visiting, 25.

To be clear, His support was not out of sympathy with the college’s longstanding mission, however liberally construed, to convert students to Protestantism, but out of a conviction of the oneness of God and religion, stressing universality and commonality of worship. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s approach bore some commonalities with those of Muslim reformist thinkers and other liberals but differed in key respects. The well-known reformer Muhammad ‘Abduh, whom ‘Abdu’l-Bahá met with during His 1887 visit to Beirut, embraced the adoption of modern science for the benefit of Islamic societies; however, he advocated for the development of Muslim schools and criticized the effect on students of attending foreign ones, for it estranged them from their own culture and religion.29Scholz, “Foreign Education,” 95. The modernizer Rashid Rida also pointed to the “corrupting” force of such schools, though conceding that those who had had adequate religious instruction could attend them without any danger of losing faith. Even so, while supportive of the education the college provided, he disapproved of participation in “Christian” services.30Scholz, “Foreign Education,” 99, 187. And though liberal figures (such as Suleyman al-Bustani, Beirut’s parliamentary representative in Istanbul) voiced support for the idea that the younger generation could transcend racial and religious differences and worship together,31Scholz, “Foreign Education,” 188. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s comments explicitly and seriously included the idea of Christians themselves going to mosques to worship as well, a possibility that others would have found difficult to imagine. His was a voice for a kind of radical equality that challenged liberals at the college and reformists in the wider society alike.

During those years, liberals at the college like Bliss had been moving SPC in directions that were increasingly consonant with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s bold vision. Giving up on converting students to Protestantism as the college’s primary goal, Bliss identified the fostering of religious harmony as integral to the college’s mission. As he put it, the “equal treatment for men of all religions” produces “an atmosphere of good will and moral sympathy among men of the most divergent religious belief.”32Annual Report by the President to the Boards of Managers and Trustees, 1915-16, 6-7, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. In response to the 1909 crisis, Bliss had reminded his board of trustees:

We must put ourselves in the place of our non-Christian students,– our Moslems, our Tartars, our Jews, our Druses, our Bahais…We must not dishonor his sense of honor; and we must not feel that the work of the College has fulfilled the mission until these men and their fellow religionists who form a great majority of the Empire’s population are touched and molded by the College influence.33Annual Report, 1908-09, 16.

In 1922 Laurens Hickok Seelye, a member of the AUB faculty, published in The Journal of Religion an article entitled “An Experiment in Religious Association” in which he presented the college’s (now university’s) religious policy as a “radical step” for a “Christian institution.”34Laurens H. Seelye, “An Experiment in Religious Association,” The Journal of Religion 2, no. 3 (May 1922): 303-04. Howard Bliss, he wrote, had redefined the “faith of the missionary,” which was not to “urge upon others conformity, but a gracious invitation…to learn together of the progressing revelation of God.”35Seelye, “Experiment,” 303. Bliss “put into actual missionary achievement the belief of every scientific student of religious experience.”36Seelye, 303. Seelye highlighted as a concrete sign of Bliss’s success the number of Muslims and other non-Christians the college had attracted.37Seelye, 304. In 1920-1921, they, in fact, outnumbered the Christians by 511 to 490, with 382 Muslims, 66 Jews, 41 Druze, and 22 Bahá’ís.38Annual Report, 1920-21, 15.

“An Experiment in Religious Association”

In the 1910s, the college’s religious instruction and “influence” increasingly involved interfaith dialogue, in which the Bahá’í students actively participated. The college chapter of the Young Men’s Christian Association, or YMCA, attracted a diverse group of students eager to discuss religious subjects, according to Bayard Dodge, Bliss’s son-in-law and successor as college president. Dodge joined the faculty in 1913 and was also executive secretary of the YMCA chapter. In his 1914 annual report for the YMCA, he wrote:

This winter about fifteen men used to gather every Sunday morning to discuss the five different types of religion which they represented. They took a keen interest, but never were intolerant or even hot-headed, so that they showed what an easy matter it is to talk over differences and reforms, without any fear of unpleasant feeling.39Bayard Dodge, Report of the Beirut YMCA, 1913-14, 8, American University of Beirut/Library Archives.

It is evident that the “five different types of religion” included Bahá’ís, along with Christians, Muslims, Druze, and Jews. The Bahá’í students had already received the college’s unofficial consent to hold their own meetings on campus, though many at the college and in the missionary community opposed the practice. On Sunday afternoons, the members of the Society of the Bahá’í Students of Beirut would “gather under the trees in the university [SPC] or in their private rooms, chanting prayers and talking over matters of religious concern.”40Zeine, “Program.”

Dodge had written: “On Sunday morning I meet a group of Moslems and Bahá’ís, who discuss all sorts of religious questions in a most broadminded way and are intensely interesting.”41Bayard Dodge to Cleveland H. Dodge, December 1913, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. In one of Dodge’s earliest letters from the College, dated 26 November 1913, he singled out the Bahá’ís for their interest in such activities: “they try to take the best out of all religions.”42Bayard Dodge to “Bub,” 26 November 1913, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. While such interfaith activities were encouraged, they were seen to take place under the umbrella of the college’s Christianity. A very small number (12 out of 177) of YMCA members were not Christians, perhaps because as non-Christians, they could join only as associate members. By Dodge’s own admission, many other such students attended “most of the meetings, but feared to have the name ‘Christian’ in any way associated with them.”43Bayard Dodge, Report, 6. Despite the disinclination felt by many students toward being part of a Christian association, however, Dodge did not yet perceive any conflict with the fact that the YMCA was the only formal organization for these kinds of activities. Ottoman pressure ultimately succeeded in forcing the college to disband all student societies, including the YMCA, in May 1916.

During the war, the college’s religious regulations underwent dramatic changes. The subsequent, and in part consequent, upsurge in enrollment of Muslim students to the college who would now be exempt from mandatory religious exercises had caused deep anxiety in Bliss, Dodge, and others. West Hall, constructed in 1914 for student activities, became a refuge for the students from the increasingly harsh wartime conditions outside the college walls. It was also a venue for the college’s experiment in religious association to break new ground. The closing of the YMCA, along with the other student societies, in 1916; the continuation of the informal interfaith discussion groups started before the war during which time “the association in worship became freer than ever”44Seelye, “Experiment,” 305. ; and the much-vaunted sense of solidarity that the war seemed to intensify – all of these had paved the way for the formal creation of a new organization, a “Brotherhood,” envisioned by Bliss in a speech at the building’s opening. In a sermon given on 8 February 1914 titled “God’s Plan for West Hall,” Bliss had identified as the new building’s “supreme purpose the awakening in the men who make use of West Hall of the spirit of service, of ‘the struggle for the life of others’”; instrumental for such a purpose, Bliss proposed, was “a West Hall Brotherhood.”45Al-Kulliyah, March 1914, No. 5, 136.

It was not until 1920, however, that the West Hall Brotherhood properly got on its feet, when Laurens Seelye arrived to become the director of West Hall. Two years later, in his aforementioned article “An Experiment in Religious Association,” he explained the emergence of the West Hall Brotherhood. Deriding the patronizing policy of associate membership for non-Christians in the YMCA, Seelye discussed the delicate balance he and others tried to achieve in making the Brotherhood “non-Christian” even while the University remained a “Christian missionary institution.”46Seelye, “Experiment,” 305-06. Important to membership in the Brotherhood was the belief that, as stated in its Preamble, “a thoughtful, sincere man, whether Moslem, Bahai, Jew or Christian can join this Brotherhood without feeling that he has compromised his standing in relation to his own religion.”47Seelye, “Experiment,” 307. A few Bahá’ís would have been among the twelve non-Christian members of the YMCA in 1913-14, as these twelve were “very equally divided amongst men of the different sects.”48Bayard Dodge, Report, 6.Yet, as with the other non-Christians, joining the Brotherhood would have been a far more acceptable alternative for the Bahá’ís. The Brotherhood’s “Pledge” did not name any single religion but only “this united movement for righteousness and human brotherhood.”49Seelye, “Experiment,” 308. In 1921, Dr. Philip Hitti, the renowned Princeton scholar who was then a young faculty member at his alma mater AUB, wrote that the Brotherhood’s “watchword shall be ‘unity through diversity.’”50Al-Kulliyah, Nov. 1921, No. 1, 4.

The Bahá’í Students’ Contribution

The Bahá’í students’ participation in such intercommunal spaces was complemented by similar experiences they had gained within their own community, both in Beirut as well as in Haifa and Egypt. Part of the reason for Bliss’s 1914 visit was to arrange for the April visits of the Bahá’í students in Beirut, 27 of whom would make the trip (out of around 30-35 total students)51Redman, Visiting, 23. For a broader overview of the Bahá’í students in Beirut, including detailed statistical information, see Richard Hollinger, “An Iranian Enclave in Beirut: Baha’i Students at the American University of Beirut, 1906-1948,” in Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years, ed. H.E. Chehabi (Oxford: Centre for Lebanese Studies in association with I.B. Taurus, 2006) 96-119.; 20 students, in two groups, visited ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in Egypt in September 1913.52Ahang Rabbani, ed., The Master in Egypt: A Compilation, Studies in the Babi and Baha’i Religions, Vol. 26 (Los Angeles: Kalimat Press, 2021) 240, 285-86. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá met with these students often during their visits (sometimes twice a day), encouraging them in their studies and asking them if their teachers “took pains to instruct the students.”53Rabbani, Master, 248. He urged them to “strive always to be at the head of [their] classes through hard study and true merit” and to “entertain high ideals and stimulate [their] intellectual and constructive forces.” 54Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98. He prioritized the study of agriculture and directly encouraged students to study medicine, in addition to subjects that would lead to careers in commerce and industry. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá also encouraged postgraduate studies, at Stanford, for example.55Rabbani, Master, 305.

Beyond their academic pursuits, however, the Bahá’í students received an education in the kind of united world ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was so interested in cultivating. He urged them to “strive to beautify the moral aspect of [their] lives” through the “divine ideals [of] humility, submissiveness, annihilation of self, perfect evanescence, charity, and loving kindness.” They must, He added, “Love and serve mankind just for the sake of God and not for anything else. The foundation of [their] love toward humanity must be spiritual faith and divine assurance.”56Star of the West 9, no. 9 (20 August 1918): 98. Not only did ʻAbdu’l-Bahá spend time with them and address them on various subjects, but the students also read copies of His talks from His 1912 trip to America.

The effect of these visits on the students was immense. As Badi Bushrui, who was among the students that visited ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in both Egypt and Haifa, later reflected, “Here is an interesting scene: the Hindu, the Zoroastrian, the Jew, the Moslem, and the atheist start singing songs of joy, praising BAHA’O’LLAH that, through His Grace, they were enabled to meet on the common-ground of Unity…”57Redman, Visiting, 24. Bushrui here is identifying people by their source communities, emphasizing the unifying effect of their attraction to the Bahá’í teachings. Indeed, the Bahá’í students were themselves a diverse group; though most were from Persia, they came from Muslim, Jewish, and Zoroastrian backgrounds. In addition, on all their visits, the students interacted with Bahá’ís from Western countries, Americans especially.

The Bahá’í students’ experience visiting ʻAbdu’l-Bahá reinforced their efforts to contribute to the life of the college, and they actively sought out spaces in which they could put into practice their spiritual education. It was through this lens that Bahá’í students participated in religious services at SPC. They were not simply tolerating the Protestant services but viewing them in this far more unifying spirit. They also took advantage of opportunities to participate in the intercommunal spaces that opened up when the services became optional for non-Christians.

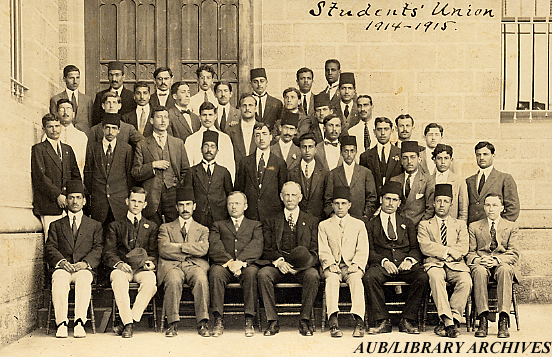

But the main venue for the Bahá’í students’ contribution to the college was the Students’ Union, which put on plays and organized a Social Service Institute and a Research Club, besides holding meetings. The most important ones were its weekly Saturday night meetings at which various topics were discussed and debated and the business meetings at which “parliamentary rules [were] observed and practiced.”58Al-Kulliyah, July 1910, No. 6, 229. There were also speaking contest meetings, election meetings, and reception meetings. The twin aims of the Union were “to cultivate and develop public speaking and parliamentary discipline in its members.”59Students’ Union Gazette, 1913, 65, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. Published every two months was the Students’ Union Gazette, the student magazine that had the longest run during this period.60Anderson, American University of Beirut, 22. The Union operated “exclusively” in English61Students’ Union Gazette, 1913, 65., and indeed in his history of AUB, Bayard Dodge refers to the Union as an “English society.”62Bayard Dodge, The American University of Beirut: A Brief History of the University and the Lands Which It Serves (Beirut: Khayat, 1958), 33. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá encouraged the Bahá’í students to perfect their English and to give talks in the language, something they practiced while visiting Him in Egypt and Haifa.63Rabbani, Master, 304.

By 1912 at least, this group was playing an active role in campus life. From the time the Bahá’í students began to form a recognizable group on campus, they became dynamic members of the Union, being elected to the Union’s Cabinet, contributing to the Gazette, participating in and winning prizes in debate contests, and also proposing subjects for debate at the Saturday night meetings. From 1912 until 1916, when all student societies were closed down, Bahá’í students were almost continuously represented in the Students’ Union Cabinet, elections for which were held twice a year. Twice Bahá’í students were elected its president; twice its vice president; at least once its secretary; once its associate secretary; twice the editor of the Students’ Union Gazette; once the president of its Scientific Department; and several times as members-at-large.

Their contributions to the Union – through the topics they suggested for debate, the talks they gave, and the articles they wrote – reveal the focus of their interests: promoting greater unity among the diverse groups of students in the service of universal peace, all the while including a dynamic role for religion. In April 1914, one student proposed that a “universal religion is possible” while another, ‘Abdu’l-Husayn Isfahani, put forth that “Universal Reformation in all the different phases of life can never be effected except through religion”64Students’ Union Gazette, 1914, 60 and Al-Kulliyah, April 1914, No. 6, 192.; Isfahani in a January 1913 speaking contest on “Is reputation an index of true greatness?” had elaborated on this conception of a “universal religion,” basing his argument on the transcendent universality of the founders of major religions – their “creative and inspiring power.”65Students’ Union Gazette, 1913, 35. Jesus Christ, Muhammad, and Buddha, he argued, through their “brilliant commanding genius” accomplished what they did in the face of societal opposition. Thus, their reputations do indicate true greatness. Isfahani also proposed that month that “racial differences do not exist.”66Al-Kulliyah, April 1914, No. 6, 192.

The Bahá’ís continued their involvement with the Students’ Union in the following decades. In 1929, for example, Hasan Balyuzi gave a talk for a speaking contest on the “religion of the future,” which would be characterized by “plasticity, absence of hypocrisy, and spirit of universal brotherhood.”67Al-Kulliyyah, June 1929, No. 8, 238.

At a time when issues of war and peace were very much of the moment, the Bahá’í students sought to promote universal peace. In the years immediately before World War I, Bahá’í students proposed antiwar debate topics, such as “war must inevitably stop,” and wrote articles such as “Towards International Peace.” One such student, Aflatun Mirza, proposed that “a universal language is essential to the progress of the world.”68Al-Kulliyyah, May 1912, No. 7, 227. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá in His talks in America and Europe had supported the establishing of a secondary, auxiliary language to facilitate greater unity and lead to peace.69Balyuzi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 330. In the 1920s, in fact, many Bahá’ís became active members of the worldwide Esperanto movement. One Bahá’í student, Zeine N. Zeine, was an enthusiastic promoter of the language on campus, giving talks on it, including, on at least one occasion, a short one in Esperanto itself.70Al-Kulliyyah, February 1929, No. 1, 99.

However, even more revealing of the way the Bahá’í students understood their contribution to this discourse was a speech given by Zeine in 1929, a talk that won a prestigious speaking contest. In “Mental Disarmament,” he claimed that such disarmament was more “necessary to peace and happiness of the world than the disarmament of the sword.” Attitudes, he continued, such as “intolerance, ignorance, hatred, prejudice” and so on “play more havoc than the cannon, and bring about strife and war.”71Al-Kulliyyah, April 1929, No. 6, 153. (Appropriately, Zeine, upon his graduation that year, was hired as assistant director of West Hall and an instructor of Sociology.) In a similar vein, the president of the Students’ Union, not a Bahá’í, at the Brotherhood’s year-opening reception in October 1926, remarked, “the Druze, the Moslem, the Jew, the Bahai, the Christian all unite together to oppose others of the same religion for the welfare of the Union.”72Students’ Union Gazette, 1926, 7-8. Back in June 1914, Badi Bushrui, who was the outgoing president of the Union, offered a succinct summary of the way Bahá’ís sought to contribute not only in their words but also in their deeds:

Let the Union, as often suggested by President Bliss, stand for universal peace and the oneness of the world of humanity. I am glad that the spirit which the college tries to infuse into her students is finding expression in the life of the Union. Racial and religious differences play no part there. The President for the first term this year was a Christian, the last President was a Bahai and the new President is a Moslem. I believe this is the biggest stride the Union has taken to be able to choose the best man without regard to religious or racial affinity.73Al-Kulliyyah, June 1914, No. 8, 26.

Furthermore, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s guidance addressed the practical outcomes of their education. In Egypt in 1913, for example, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá told the students that it was “his hope that they would make extraordinary progress along spiritual lines as well as in science and art; so that each one might become a brilliant lamp in the world of modern civilization, and upon their return to Persia that country might profit from their acquired knowledge and experience.”74Rabbani, Master, 241. Out of 24 Master’s theses written before 1918, five were written by Bahá’í students.75Hollinger, Distant Relations, 111. Two theses, both written in 1918, exemplify this focus on serving the best interests of their nation. “Social Evils or Hindrances to Persia’s Progress” and “Persia in Transformation,” both written by Bahá’í students, identified elements of Persia’s religious, social, and political life needing attention and articulated a progressive vision for the country, assigning prominent places to education and the rights of women.76Azizullah Khan S. Bahadur, “Social Evils or Hindrances to Persia’s Progress” (MA thesis, American University of Beirut, 1917); Abdul-Husayn Bakir, “Persia in Transformation” (MA thesis, American University of Beirut, 1918).

In a letter to his father dated 22 June 1914, Dodge commented on this mission of the Bahá’í students. “Most of these students travel to the College from three to four weeks away,” he related, and “speak in a most serious way of getting an education here and then returning to help their unfortunate land.”77Bayard Dodge to Cleveland H. Dodge, 22 June 1914, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. Dodge’s initial encounters with the Bahá’í students in 1913 led him to state that “they uphold all sorts of good reform movements.”78Bayard Dodge to “Bub,” 26 November 1913, Box 4, The Bayard Dodge Collection, American University of Beirut/Library Archives.

The Bahá’í students also contributed to the college-wide efforts to render service to the local community, efforts which greatly accelerated during the war, including medical relief activities, among others. Not long after the war broke out, most of the Bahá’ís in Haifa and ‘Akká, including Badi Bushrui and another recent SPC graduate Habiballah Khudabakhsh, later known as Dr. Mu’ayyad, were received as guests in the Druze/Christian village of Abu-Sinan.79Balyuzi, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 411. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s warm relationship with the village leaders had made this arrangement possible. In an article titled “A New Experience,” published in a fall 1915 number of the Students’ Union Gazette, Bushrui relates how Dr. Mu’ayyad started a medical clinic in the village, performing many operations and treating a variety of conditions over a period of eight months. 80Bayard Dodge, “Education As a Source of Good Will” in The Bahá’í World (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1933) 4: 370. Bushrui and an American Bahá’í woman, Lua Getsinger, acted as nurses and assistants; Bushrui also taught some of the children. Such an experience of social service would have resonated deeply with the emerging ethos of the college, to be sure.

The Bahá’í students’ contributions became a recognized fact of life at the college over the coming decades. In an article titled “Education as a Source of Good Will” published in the 1930-32 volume of The Bahá’í World, President Bayard Dodge outlined the university’s mission, confirming AUB’s strong relationship with the Bahá’ís and its view of them as a like-minded group. From Dodge’s perspective, the university’s “interpretation of the gospel of Jesus and the teachings of the prophets” was “similar to that proclaimed by the great Bahá’í leaders,” and so there had “naturally been a bond of sympathy” between the university and the Bahá’ís.81Bayard Dodge, “Education As a Source of Good Will” in The Bahá’í World (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1933) 4: 370. As previously noted, the Bahá’ís’ active involvement before and during the war in the interfaith discussion groups made quite a deep impression on Dodge. Writing in 1930, when there were three Bahá’ís on the university staff and twenty-six students, Dodge listed the twenty-eight graduates of the university (there were in fact thirty82Hollinger, Distant Relations, 104. Hollinger also notes that by 1929, about 60 to 70 Bahá’í students in total had studied at SPC/AUB; by 1940, around 300 Bahá’í students had been educated in Beirut, overall. It was in the mid to late 1910s that the Bahá’í students were most statistically significant, however, with as many as 44 students at the college in 1919.) up to that point, adding that they had “become a great credit to their Alma Mater.”83Dodge, “Education,” 4: 370. The list included two women trained as nurses and midwives (women were first admitted to the university in 1921). Dodge himself noted that the list did not include the many Bahá’ís who spent time at the university but never graduated. Dodge detailed three distinguishing qualities of the Bahá’í students:

In the first place, they have acquired from their parents an enviable refinement and courtesy. As far as I can tell, all of them have been easy to get along with, good natured with their friends, and polite to their teachers. Their reputation for good manners and breeding is well established.

In the second place, the Bahá’í students have been marked by clean living and honesty. The older men have had a good influence on the younger ones, so that it is a tradition that they avoid bad habits. Every Sunday afternoon they meet together for devotional and social purposes at the house of Adib Husayn Effendi Iqbal. The older students are able to keep in touch with what the younger ones are doing and their influence is worth as much as a whole faculty of teachers.

In the third place, the Bahá’ís intuitively understand internationalism. They mix with all sorts of companions without prejudice and help to develop a spirit of fraternity on the campus… 84Dodge, “Education,” 4: 371.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s qualified encouragement of modern education bore fruit in the activities of these Bahá’í students. While taking advantage of their academic opportunities, they were also guided by moral principles, perceiving no conflict between their scientific and religious education. While highly cohesive and united as a group, they sought to be a unifying force at the school, promoting the oneness of humanity and universal peace among their classmates “without prejudice.” Becoming an established presence at a time when SPC was liberalizing its approach to religious education, the Bahá’í students found the college a receptive space in which to express their identities as Bahá’ís, and, inspired by the example and teachings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, it is clear that they made an important contribution to the life of the college. Their example shows, moreover, that when a group like the Bahá’í students is empowered in such a setting, significant results can accrue for the whole.