“Endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”1Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (John Murray, 1859), 490. —Charles Darwin

One of the most astonishing aspects of our planet is the diversity of life that has evolved over millions of years. Scientists estimate that 8.7 million species inhabit the Earth. Our knowledge of this diversity is still at an early stage; 14% of terrestrial species and 9% of marine species have been documented. This enormous gap in knowledge about the diversity of life is surpassed by an even greater gap in how we might preserve and protect it.2Camilo Mora et al., “How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?” PLOS Biology (2011): 1, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.

The rich tapestry of life on Earth has been referred to as “the library of life.” Today, this wondrous library is on fire. Biodiversity loss is proceeding at rates unprecedented in human history. Geological records reveal that there have been five mass extinctions of life on Earth, each driven by natural, catastrophic events. For decades evidence has been mounting that we are currently in a sixth mass extinction, mainly driven by anthropogenic influences.3Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (Henry Holt and Company, 2014), 3. We are witnessing the unraveling of the tapestry of life through the loss of species, the decline in genetic diversity, and the compromising of essential ecosystem functions.

Many who are aware of this crisis are trying to rescue as many “books” as possible from the library of life and in most cases are, at best, only able to take a cursory glance at the titles on the covers before they are lost forever. Species that evolved over millions of years are becoming extinct before science can account for or study them.4E.O. Wilson, The Diversity of Life (Harvard University Press, 1992), 15. That the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems are in a state of crisis calls for an unprecedented, monumental transformation. Turning the tide will require the confluence of an array of factors.

Interconnectedness and Complexity

The dominant understanding of humanity’s relationship to nature undergirds its collective behavior towards the natural world. With regard to the mutualism of existence, the Bahá’í writings encourage us:

Reflect upon the inner realities of the universe, the secret wisdoms involved, the enigmas, the interrelationships, the rules that govern all. For every part of the universe is connected with every other part by ties that are very powerful and admit of no imbalance.5‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, no. 137: https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/abdul-baha/selections-writings-abdul-baha/6#394483842.

Ecology, the study of relationships, connections, and interactions among organisms and their environment, confirms that biodiversity underpins the functioning of ecosystems and the production of ecosystem services, such as crop production, pollination, water purification, coastal protection, and climate regulation—services that are essential for human well-being and flourishing.

Social, cultural, economic, technological, institutional, and ecological variables interact in complex ways that drive global declines in nature. Given the complexity of the interactions of these social-ecological systems, it is difficult to predict, plan for, and manage the repercussions of biodiversity loss and the degradation of natural systems. Consider, for example, the problem of ecological cascades in which the loss of a keystone species can disrupt an entire ecosystem and can lead to the loss of other species and, at times, the breakdown of an entire ecosystem, in ways that are often poorly understood. For instance, the removal of wolves from Yellowstone National Park in the early twentieth century led to an overpopulation of elk, which in turn overgrazed young trees and vegetation. This overgrazing caused a significant decline in beaver populations, which rely on trees for building dams, and even altered the flow of rivers. The reintroduction of wolves decades later was one of a web of factors that contributed to the restoration of balance, demonstrating the intricate connections within ecosystems that can unravel when key species are lost.5William J. Ripple and Robert L. Beschta, “Wolves and the Ecology of Fear: Can Predation Risk Structure Ecosystems?” BioScience, 54, no. 8 (2004): 755-766, https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/54/8/755/238242.

Once cascades are set in motion, there are usually time lags before tipping points are reached and the related effects are felt. Symptoms of transgressing such tipping points often manifest themselves in the effects on the economies that depend on the healthy functioning of ecosystems to ensure a sustained flow of goods and services. Individuals, institutions, and communities need to develop the capacity to navigate the inherent unpredictability of these systems in ways that are good for nature and people.

A recognition of these interactions and relationships raises many questions: How can our individual relationship with nature be rethought to create a more sustainable future? How can collective volition be harnessed towards preserving and restoring natural systems? And, recognizing that local, regional, and global governance are all needed to address the challenges of biodiversity and ecosystem degradation, how can interactions between these three levels become coherent, integrated, and harmonious?

Economies within Ecosystems

Economic systems are embedded in social systems, which are in turn embedded in the ecosystems that constitute the biosphere of our planet. The compartmentalization of these systems has greatly influenced the way in which we consume and produce. A much deeper consciousness of our interdependence with each other and the biosphere that supports all life is needed if we are to create a sustainable future. The Universal House of Justice has highlighted the seriousness of the problem, saying, “The deepening environmental crisis, driven by a system that condones the pillage of natural resources to satisfy an insatiable thirst for more, suggests how entirely inadequate is the present conception of humanity’s relationship with nature.”6Universal House of Justice, Letter to the Bahá’ís of Iran (2 March 2013): https://www.bahai.org/r/599204606.

This inadequate conception of our relationship with the natural world plays out in our patterns of consumption that have negative impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems. For example, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has estimated that fish stocks are in decline with two-thirds being fished to the limit or overfished and that 70% of the fish population is fully used, overused, or in crisis.7Resumed Review Conference on the Agreement Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (United Nations Department of Public Information, 2010), 1-2: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/reviewconf/FishStocks_EN_A.pdf. Food production systems are the main drivers of biodiversity loss globally and threaten 86% of the species at risk for extinction.8United Nations Environment Programme, “Our global food system is the primary driver of biodiversity loss,” press release (3 February 2021): https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/our-global-food-system-primary-driver-biodiversity-loss The Universal House of Justice has pointed out that “every choice…as employee or employer, producer or consumer, borrower or lender, benefactor or beneficiary—leaves a trace, and the moral duty to lead a coherent life demands that one’s economic decisions be in accordance with lofty ideals, that the purity of one’s aims be matched by the purity of one’s actions to fulfill those aims.”9Universal House of Justice, Letter to the Bahá’ís of the World (1 March 2017): https://www.bahai.org/r/904550633.

Human Nature

The reductive and limiting view of human nature as self-interested, coldly rational, and driven by the desire to maximize consumption and profit has been devastating to humanity’s relationship with nature. Our natural systems have come to be seen as the repositories of seemingly infinite resources from which products and services can be derived to fulfill unchecked human needs and wants. The situation is further exacerbated by the “distancing” of consumers from the sources of these products and services. Species extinctions and ecological degradation are often out of sight and out of mind. This seemingly invisible ecosystem degradation and loss of biodiversity are often considered as externalities to the economic system and are not reflected in the costs incurred in harvesting and exploiting natural resources. The disconnection between the consequences of our actions and their effects on nature is especially pronounced in urban centers, where most of humanity now resides.

Growing consciousness about the consequences of our choices on the natural world coupled with an awareness of human capacity to mitigate these negative impacts has led, in some cases, to a deeper reflection on human nature and how our understanding of it affects our sense of self, our relationship with nature, and our purpose in life. A growing number of voices are casting doubt on the notion that we are purely self-interested beings bent solely on consumption and exploitation.

The Bahá’í writings assert that human beings possess a dual nature. While our lower nature inclines us to selfishness, greed, and exploitation, our higher nature, when cultivated, seeks transcendence and is inclined toward stewardship, altruism, self-restraint, and reciprocity. Neglect of this higher nature has led to an inaccurate view of the human being’s relationship to others and to the physical world and a neglect of an essential part of human development and fulfillment.

The Role of Religion

Bahá’ís view true religion as a system of knowledge and practice that, like science, evolves as humanity advances from one stage of collective development to the next. Conceptions and practices of religion that are rooted in the distant past cannot release the system’s potential to address contemporary environmental challenges, just as science as it was conceived and practiced in earlier stages of civilizational development is not adequate for the challenges humanity faces today.

In its purest form, religion seeks to nurture and develop the higher nature in human beings, fostering ethical behavior through spiritual education and the application of spiritual principles in service to society. As the Universal House of Justice has written, religion “reaches to the roots of motivation”:

When it has been faithful to the spirit and example of the transcendent Figures who gave the world its great belief systems, it has awakened in whole populations capacities to love, to forgive, to create, to dare greatly, to overcome prejudice, to sacrifice for the common good and to discipline the impulses of animal instinct.10Universal House of Justice, Letter to the World’s Religious Leaders (April 2002): https://www.bahai.org/r/392291398.

Today, to serve as a force for civilization building, religion must cultivate in humanity a consciousness of its oneness and wholeness and the critical need for a harmonious relationship with the natural world. Bahá’í communities around the world are dedicated to discovering this potential, in collaboration with like-minded individuals and groups.

One of the ways it is learning to release this potential is through the development of an evolving system of spiritual education that aims to awaken in populations requisite qualities and capacities.

For example, among its wide-ranging educational endeavors is the Bahá’í community’s junior youth spiritual empowerment program, which “encourages thoughtful discernment at an age when the call of materialism grows more insistent.”11Universal House of Justice, Letter to the Bahá’ís of the World (1 March 2017): https://www.bahai.org/r/963073955. The study of thought-provoking texts nurtures in junior youth spiritual qualities and attitudes, enhances their knowledge and understanding, and cultivates their skills. Study is complemented with service projects, often in relation to safeguarding the local habitat, that help youth translate what they learn into meaningful action. In this way their higher nature is nurtured, and they begin to see how their efforts can contribute to stewardship of the natural world. As their capacity for collective action grows, they are able to engage in projects with greater levels of complexity.

While the experience of the Bahá’í world is as yet modest across the planet, there are now countless initiatives undertaken by adolescents inspired and prepared to contribute to the betterment of the world. Among these was a service project devised by a group of junior youth in Okcheay, Cambodia. They planted trees along a stretch of road to improve air quality and provide shelter from the heat, but the community witnessed a further impact later in the year when the trees protected the road from severe soil erosion caused by a flood.12“Youth initiative in Cambodia reduces soil erosion during floods,” Bahá’í World News Service (14 April 2021): https://news.bahai.org/story/1502/.

Nature as a Reflection of the Sacred

The human-nature relationship is fundamentally spiritual and cannot be described purely in material or economic terms. Reconceptualizing this relationship influences how we view nature and how we choose to interact with it.

The Bahá’í writings describe nature as a reflection of the sacred and imply that meditation on various aspects of the natural world can serve as a means for drawing closer to the Divine: “When…thou dost contemplate the innermost essence of all things, and the individuality of each, thou wilt behold the signs of thy Lord’s mercy in every created thing.”13‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, no. 15: https://www.bahai.org/r/899707086.

The growth in spiritual consciousness engendered by such contemplation inspires humility in the human soul and strengthens a spiritual connection with the natural world. Bahá’u’lláh has written that every person conscious of the sacredness of nature cannot “while walking upon the earth” but feel abashed, “inasmuch as” we are “fully aware that the thing which is the source of” our “prosperity,” “wealth,” “might,” “exaltation,” our “advancement and power is, as ordained by God, the very earth which is trodden beneath the feet of all…. There can be no doubt that whoever is cognizant of this truth, is cleansed and sanctified from all pride, arrogance, and vainglory.”14Bahá’u’lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf (Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988), 44: https://www.bahai.org/r/828250778.

Harnessing Collective Will

Intimately connected to our relationship with nature is our relationship with each other. Maintaining healthy ecosystems requires that communities and indeed whole societies act together based on a consciousness of the oneness of humankind. Religion can inspire such collective consciousness and foster collective will and action.

In the village of Agua Azul in Norte del Cauca, Colombia, for instance, thousands of people connected to the Bahá’í community started consulting about the revival of the natural habitat when plans to build a local House of Worship were initiated in 2012. A series of community consultations gave “rise to an acute awareness about the physical environment and its relationship to the spiritual and social well-being of the population.”15“In rural Colombia, seeds of transformation take root,” Bahá’í World News Service (29 March 2015): https://news.bahai.org/story/1047.

Over decades the region’s lush native forest, teeming with life and land cultivated by local farmers, had been taken over by sugar cane farms. After 2012, however, communities began to restore the land’s rich ecological diversity through a reforestation project. From near and far, local inhabitants contributed seeds and plants to a collective initiative that they viewed as belonging to the whole population.

In addition to restoring the biophysical aspects of the region, the project restored the equally important biocultural aspects. “This native forest that we are going to grow should be a school, should be a place of learning,” said one of the remaining local farmers in the early days of the project. His longing for knowledge of the ecology of the region to be passed down to the younger generations would be fulfilled.16“In rural Colombia, seeds of transformation take root,” BWNS: https://news.bahai.org/story/1047. Students now gather regularly on the grounds of the Bahá’í House of Worship and the native forest, called the “Bosca Nativa,” to study and plan projects together.

One project by participants in the Preparation for Social Action (PSA) program was to plant and nurture 10,000 trees. As a step towards this goal, a call was made to the communities of Jamundí and Cali to come together for a community meeting, or “minga,” to consult about engaging in a project called “Transforming the Environment,” with the goal of planting 600 trees. In response, in just one day, more than 500 individuals planted 565 saplings—a practical expression of the participants’ heightened consciousness that ties of integration are fortified in their communities through a strong connection with nature. Given that forests operate on much longer timescales than human lives, an important aspect of this initiative is that children and adolescents are engaged in a process of learning and teaching. As they gain insights and skills in regenerating the native forest and strengthening community ties, they can pass this knowledge on to future generations, ensuring the long-term sustainability of the endeavor.

From Tragedy of the Commons to Stewardship of the Commons

These examples illustrate how communities can begin to overcome an issue that often lies at the heart of managing biodiversity and ecosystems, namely, the collective management of common pool resources and the ecosystems from which they are derived, such as fish from coral reefs and timber from forests.

Common pool resources are often shared among diverse groups with varying interests and needs. Over time, such resources are overused and may become depleted. Theoretically, if all users cease to exploit the common pool resource, the sustainability of the resource is ensured. However, such a situation introduces a dilemma: if one group desists from harvesting and another does not, the group that desisted stands to lose any short-term gains that it potentially would have received. Further, the group that persisted benefits from those short-term gains and the resource still eventually collapses. This is referred to as “The Tragedy of the Commons” and has been a persistent problem in ecology and environmental management that has led to proposals of various solutions for managing the resources derived from biodiversity and ecosystems.17Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, no. 3859 (1968): 1243-1248, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.

Such solutions often include advocating either for privatization of ownership or for government control of the resource, in the conviction that because local users will inevitably deplete a resource, some form of external intervention is needed. Underpinning such negative assumptions is belief in the inherent competitive nature of groups, the dominance of self-interest over collective interest, and the oversimplification of complex social-ecological interactions. And these ideas, in turn, shape the formulaic models that outside entities promote to solve the problems of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation at the local level. Such simplistic approaches often involve attempts to isolate a specific part of the local or regional system without due consideration to its interconnectedness to the whole.

Decades of research by Elinor Ostrom and other economists and scientists have shown that the “Tragedy of the Commons” is not inevitable—and, indeed, that local communities have, in many cases, managed common pool resources in ways that conserve and protect the resource and ensure that there is equitable distribution of rights and access to it.18Elinor Ostrom et al., The Drama of the Commons (National Academy Press, 2002), 2: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/10287/chapter/1.

Such stewardship of the commons is more likely when certain elements are in place. For example, face to face communication as opposed to computer-mediated communication often leads to higher levels of cooperation and collaboration, leading to higher returns for the parties involved.

In contrast, overreliance on top-down interventions reduces reciprocity, stymies local collective action, and overlooks the ability of communities to self-regulate and comply with clearly stated regulations when their rationale is understood. There is also evidence that local indigenous knowledge, complemented by scientific insights, is an important factor in restoring and protecting common pool resources. The importance of social learning and adaptation is also emphasized in many of these case studies.19Erling Berge and Frank van Laerhoven, “Governing the Commons for two decades: A complex story,” International Journal of the Commons 5, no. 2 (2011): 168, https://thecommonsjournal.org/articles/10.18352/ijc.325.

While there has been significant progress in both the theory and practice of environmental management, garnering the combined will of communities, societies, and humanity as a whole requires agreement about shared fundamental principles and values that serve as a compass for diverse stakeholders and help mobilize them in pursuit of common aspirations and goals. Alas, too often, human affairs are characterized by competition and conflict, which do not enable diverse groups to identify such common aspirations and the principles that underlie them, handicapping endeavors that seek environmental stewardship and conservation.

In this context, the Bahá’í community sees religion as a source of universal principles around which communities organize themselves and a potent force for harnessing collective action and channeling it towards addressing the complex issues facing our societies.

Over the last twenty-five years the Bahá’í community has striven to systematically engage in a collective process of capacity building aimed at applying spiritual principles—such as justice, the equality of women and men, the harmony of science and religion, universal education, and the oneness of humanity—to address both social and environmental issues. A prominent feature of this process entails bringing together increasing numbers of people in regular, periodic reflection spaces to learn about how to address the challenges facing their local, regional, and national communities. In such spaces, participants seek to consult together in an atmosphere of unity and cooperation. Given the complex nature of the issues under consideration and the long-term, sustained action needed to address them, participants strive to operate in a mode of learning, seeking increasing levels of unity of thought and action, and refining such action through reflection on experience.

In such spaces dichotomous notions such as “us” vs. “them”, “top down” vs. “bottom up”, “individual rights” vs. “collective rights” etc., yield to more mature conceptions of the relationships that form the foundation of a community’s approach to collective action. These reflection spaces are complemented and bolstered by educational programs aimed at improving both the spiritual and material dimensions of society and, in so doing, nurture relationships based on cooperation and reciprocity, mutual aid and assistance, and a growing recognition of the interconnectedness of humanity and of its relationship to the planet’s biosphere.

Zambia provides an illustrative example of how such a process is unfolding in areas where the PSA program is focusing on the interconnectedness of ecosystems. The insights gained from the educational materials in the program and from the community consultations they inspire, has led to an assessment of and plans to restore some of the ecosystems in the area. For instance, the program has worked with a community whose fish stocks in small ponds have been depleted. Along with efforts to revive the ponds, the participants have engaged in community outreach aimed at raising awareness among the residents about how to fish in more sustainable ways to prevent further depletion of this resource.20Prepared by the Office of Social and Economic Development, For the Betterment of the World (Bahá’í International Community, 2018), 53: https://bahai-library.com/pdf/o/osed_betterment_world_2018.pdf.

In other parts of Africa, the PSA program is assisting participants to approach agriculture in a manner coherent with the spiritual insights and approaches underlying community development. Participants engage in action-research based on scientific approaches and the experience of farmers in other parts of the world. The adaptation of technology is weighed in terms of its effect on community life. Further, participants learn about organic fertilizers, composting, and managing a seed bank. All these topics have implications for biodiversity and ecosystem management: when practiced without due regard to the adaptation of technology and other inputs, agriculture can contribute greatly to biodiversity loss and to compromising ecosystem integrity, while seed banks play a vital role in maintaining crop diversity in an area. And beyond the practical elements of the program, participants gain greater consciousness about the land, learning to see it as a living thing with which humans have a reciprocal relationship.

These fledgling endeavors provide glimpses into the capacity of local communities to take charge of their own efforts to restore, protect, and conserve common pool resources. They illustrate how insights generated by spiritual and scientific knowledge can crystallize into collective action, showing that the “Tragedy of the Commons” need not be the inevitable fate of communities seeking to manage common pool resources; rather, by creating environments in which religion and science can inspire and guide people, stewardship of the commons can become a tangible reality.

Regional and Global Governance of the Biosphere

Consideration, of course, must also be given to biodiversity, ecosystems, and ecosystem functions that exist at regional and global scales and operate beyond the purview of national jurisdictions. Examples include coral reefs, the atmosphere, the deep ocean, and the polar regions, particularly Antarctica. The Amazon rainforest ecosystem operates within a national jurisdiction, Brazil, but has supranational effects. Coral reefs, while spatially spread out in terms of geographic location, nevertheless form a network of nurseries that sustain regional and global fish stocks. Social, ecological, and economic systems operating at the local, regional, and global levels are interdependent and often linked in ways that are not well understood. These systems are described as being “teleconnected” or “tele-coupled”. Greater coordination and collaboration among institutions and entities across scales will allow regional and global governance structures to manage and regulate these systems.

In the absence of such regional and global governance structures, scientific advances and access to lavish funds in many countries and within some private companies allow for unsustainable and inequitable management. Several examples illustrate this point well:

- The patenting and harvesting of marine genetic resources contribute to the development of important medicines.21Robert Blasiak et al., “The ocean genome and future prospects for conservation and equity,” Nature Sustainability 3 (2020): 591, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0522-9. This genetic material is arguably the common heritage of all humanity, but without regional and international governance to ensure equal access to the potential benefits of these resources, the risk of the more privileged members of the human family having exclusive access to them looms large.

- The management of fish stocks in the open ocean can ensure sustainability, but while laws and conventions exist for national maritime boundaries, there is great ambiguity in terms of the legislative frameworks governing fisheries operating in these regions of the ocean. This has contributed greatly to the unsustainable harvesting of fish stocks and has led to their current decline and, in some cases, their total collapse.

- Due regard to the role and protection of pollinators contributes greatly to food production. However, there is growing evidence of a significant global decline in pollinators. Since the majority of crops depend on some form of pollination, this could lead to a crisis in the global food production system and has the potential to negatively impact the food supply of billions of people.

Over the past century, a rising consciousness about the critical role biodiversity plays in the functioning of the biosphere has led to the development of a host of international conventions and treaties aimed at protecting the earth’s library of life. These include the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Convention on Conservation of Migratory Species, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the World Heritage Convention, the International Plant Protection Convention, and the International Whaling Commission. These treaties and conventions play an important role in assisting nation states to understand the interdependence of the global biosphere and in many cases attempt to include countries in binding agreements to protect and conserve biodiversity and ecosystems. Supporting these efforts, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) strives to ensure that governments and policymakers have access to essential scientific knowledge for the “conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, long-term human well-being and sustainable development.”

As promising as these developments have been, their many shortcomings need to be addressed if the global community is to take serious steps to bend the curve of biodiversity loss and restore decimated ecosystems. Voluntary commitments by nation states, while laudable, do not ensure compliance. Once a species is lost, it cannot be recovered. In an interdependent and interconnected world in which intertwined economies and ecosystems are threatened, the risk of non-compliance is too great, and time is ticking.

The Bahá’í writings are unequivocal about what humanity needs today: the current structure of global governance needs to evolve. Yet the Bahá’í community recognizes that the path to harvesting the fruits of this evolution is fraught with setbacks, struggle, and conflict. As the Universal House of Justice has observed:

Certain shared ethical principles, which seemed to be in the ascendant at the start of this century, are eroded, threatening the prevailing consensus about right and wrong that, in various arenas, had succeeded in holding humanity’s basest tendencies in check. And the will to engage in international collective action, which twenty years ago represented a powerful strain of thinking among world leaders, has been cowed, assailed by resurgent forces of racism, nationalism, and factionalism.22Universal House of Justice, Letter to the Bahá’ís of the World (18 January 2019): https://www.bahai.org/r/963030050.

Despite this retrogression, there is also the recognition that such crises have, in the past, opened the way for change and transformation. Whatever the next step in the evolution of global governance, it must be bolder and more decisive than anything humanity has established to date. The urgency of the threats to our planet demands such audacity.

Ultimately, Bahá’ís believe that the realization of such a vision will require a “historic feat of statesmanship from the leaders of the world.”23Universal House of Justice, Letter to the Bahá’ís of the World: https://www.bahai.org/r/931252854. It is apparent that such conditions do not yet exist. Religious leadership is also challenged to reflect deeply on its role in addressing the existential threat before us: “Great possibilities to cultivate fellowship and concord are open to religious leaders,” wrote the Universal House of Justice in 2019.24Universal House of Justice, Letter to the Bahá’í s of the World: https://www.bahai.org/r/739189185.

It is against such a backdrop that Bahá’ís strive to contribute to discourses in their national communities and internationally. They make efforts to contribute to and advance thought around a host of societal concerns, including environmental issues;25See https://www.bic.org/sites/default/files/pdf/one_planet_one_habitation.pdf for an example of a recent contribution at the international level. they seek to learn from the ongoing discourses and, when opportunities arise, strive to identify the root causes and relate them to the relevant spiritual principles. Bahá’ís are also focused, in collaboration with others, on how to garner collective thought and action to address the root issues of our time, often through emphasizing the need for applying the principles of consultation in collective decision-making, and of the oneness of mankind and of justice as essential elements of advancing thought and action at regional and global levels.

The Bahá’í writings point toward a future in which local, regional, and global governance will be appropriately coordinated and strengthened to ensure the safeguarding of humanity’s natural resources while protecting the rights and autonomy of each distinct population.

Conclusion

Over a century ago, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá offered the following reflection in a talk at Stanford University: “The elements and lower organisms are synchronized in the great plan of life. Shall man, infinitely above them in degree, be antagonistic and a destroyer of that perfection?”26‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “Talk at Leland Stanford Junior University, Palo Alto, California, 8 October 1912,” Promulgation of Universal Peace (Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982): https://www.bahai.org/r/683130715. In many ways, that question is more relevant today than ever before, and the current state and future projections of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation can invite feelings of despair. Yet the Bahá’í writings provide a more hopeful perspective, asserting that humanity is in a state of transition, moving painfully through the period of adolescence towards maturity. Navigating this critical period in the development of mankind and the planet is among the most critical challenges of our generation and those to come.

Ultimately, such a challenge calls for a common vision and collective will, and a reconceptualization of our relationship with nature and among ourselves. It demands courageous and bold leadership, and an evolution of our governance structures at all levels. It requires both tapping into our growing store of scientific knowledge and technological advances while also drawing on the system of religion to raise consciousness, cultivate our higher nature, and learn how to translate spiritual principles into reality.

OXFORD, United Kingdom — The International Tree Foundation is in the midst of an ambitious plan—plant 20 million trees in and around Kenya’s highland forests by 2024, the organization’s centenary.

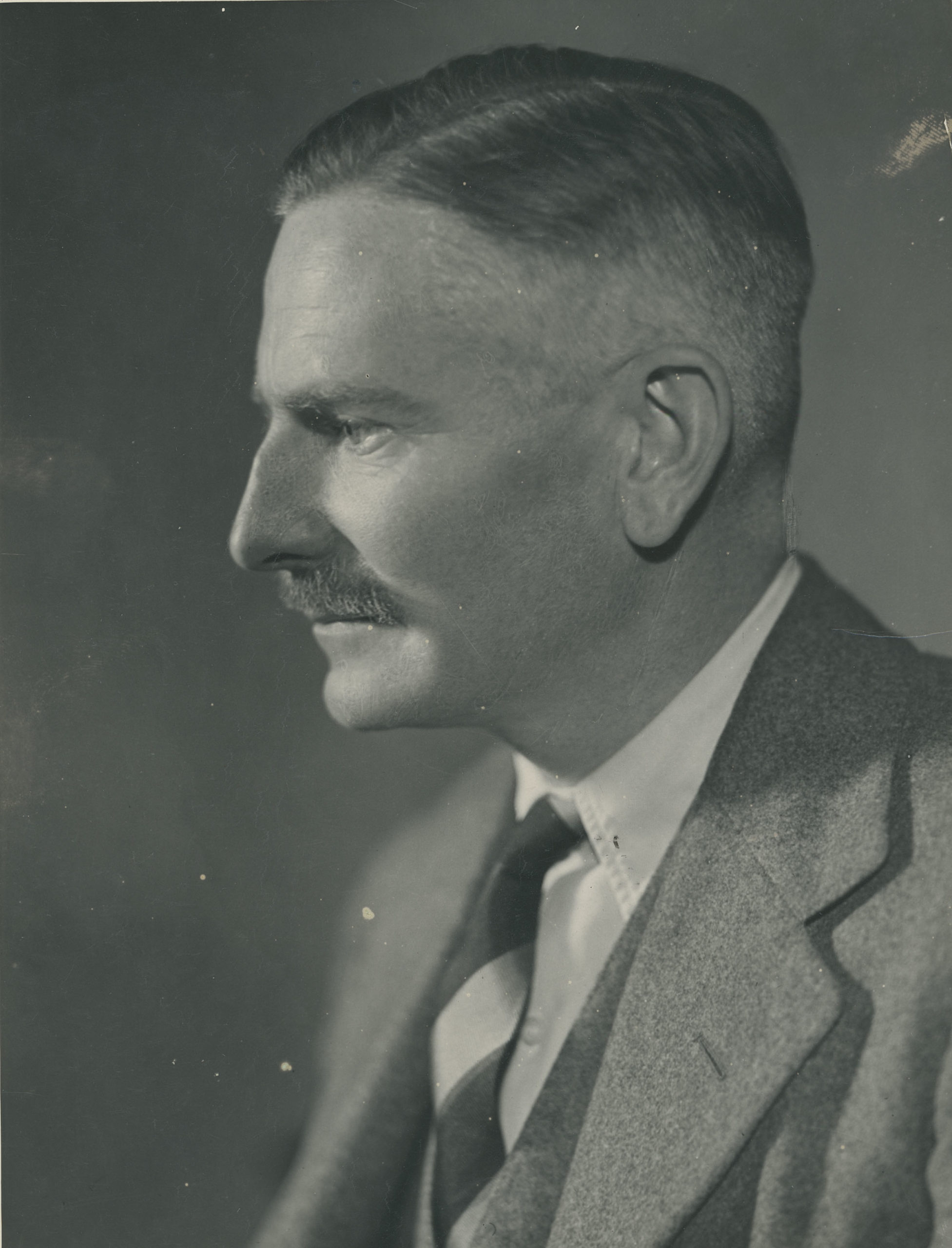

That goal is one of the many living expressions of the ideals espoused by Richard St. Barbe Baker (1889-1982), founder of the organization. Mr. Baker, who was best known as St. Barbe, was a pioneering environmentalist and early British Bahá’í who had a far-reaching vision and initiated practices that have become common and widespread today.

A re-evaluation of this influential environmental pioneer is now under way, thanks to the work of the International Tree Foundation and the publication of a new biography. The recent attention comes at a time that the consequences of global climate change are increasingly apparent to humanity.

“Long before the science of climate change was understood, he had warned of the impact of forest loss on climate,” writes Britain’s Prince Charles, in the foreword of the new biography about St. Barbe. “He raised the alarm and prescribed a solution: one third of every nation should be tree covered. He practiced permaculture and agro-ecology in Nigeria before those terms existed and was among the founding figures of organic farming in England.”

Having embraced the Bahá’í Faith as a young man in 1924, throughout his adventurous life, St. Barbe found in the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh the embodiment of his highest aspirations for the world. His deep faith was expressed in a love for all forms of life and in his dedication to the natural environment.

“He talks about the inspiration he received from the Faith and from the writings of Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá,” explains Paul Hanley, the author of a new biography about St. Barbe—Man of the Trees: Richard St. Barbe Baker, the First Global Conservationist. “St. Barbe had a world embracing vision at a time when that wasn’t really common. His frame of reference was the whole world.”

St. Barbe noted this connection with Bahá’u’lláh’s vision of the oneness of humanity when he went on pilgrimage to the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh.

“(H)ere at Bahjí (Bahá’u’lláh) must have spent his happiest days. He was a planter of trees and loved all growing things. When his devotees tried to bring him presents from Persia the only tokens of their esteem that he would accept were seeds or plants for his gardens,” St. Barbe later wrote in his diary, quoted in Mr. Hanley’s book.

St. Barbe then recalled a passage from Bahá’u’lláh’s writings: “‘Let not a man glory in this, that he loves his country; let him rather glory in this, that he loves his kind.’ Yes, I thought, humankind, humanity as a whole. Was it not this for which I had been striving to reclaim the waste places of the earth? These were the words of a planter of trees, a lover of men and of trees.”

St. Barbe also maintained a sustained contact with Shoghi Effendi, who encouraged him in dozens of letters and sought his advice when selecting trees for Bahá’í Holy Places in Akka and Haifa. St. Barbe described how the inscribed copy of The Dawn-Breakers that Shoghi Effendi sent him became his “most treasured possession.”

“I would read it again and again, and each time capture the thrill that must come with the discovery of a New Manifestation,” St. Barbe wrote.

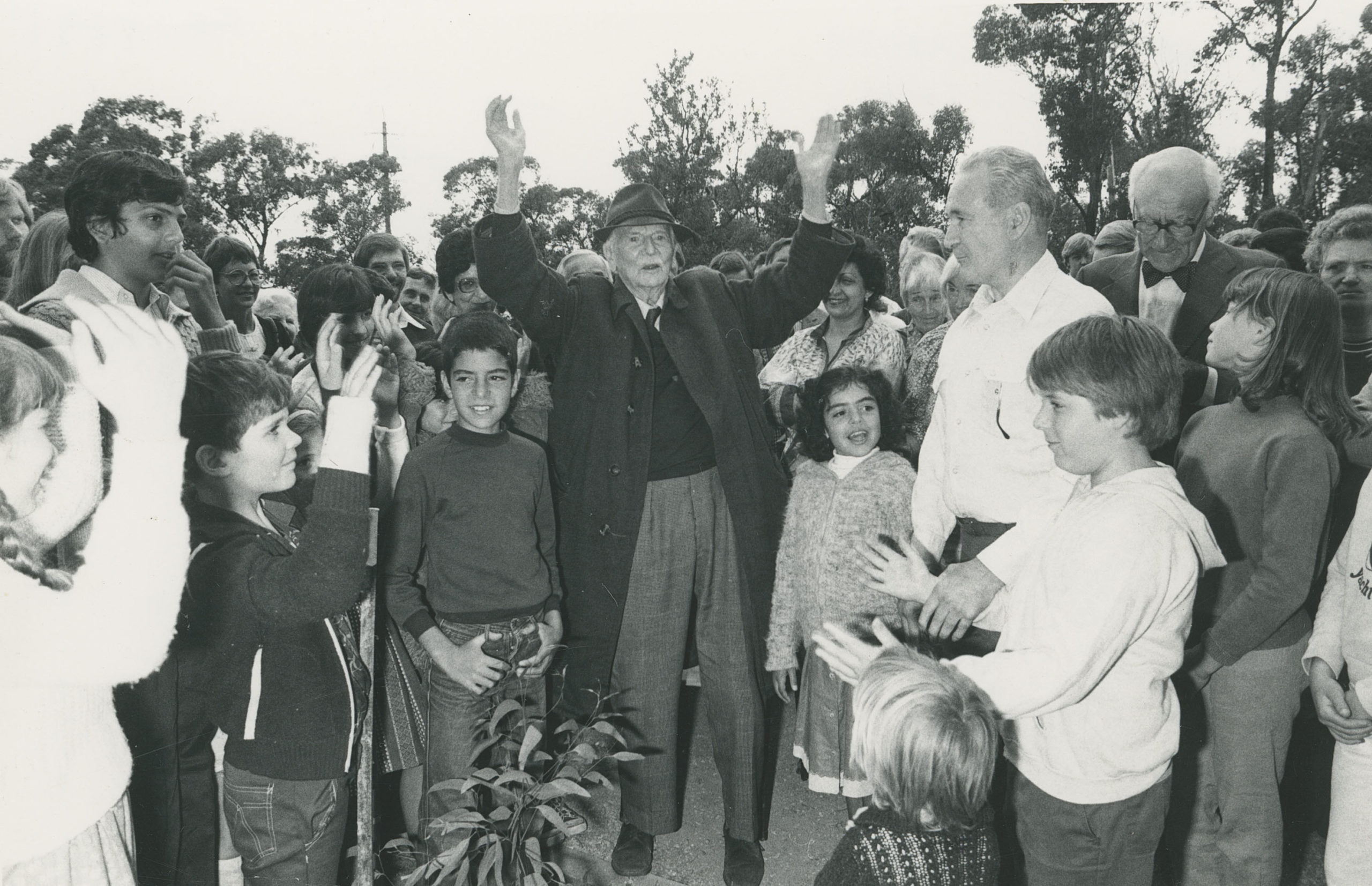

The International Tree Foundation, which St. Barbe originally named Men of the Trees, is just one of many organizations he established in his lifetime. It is estimated that, as a result of his efforts, the organizations he founded, and those he assisted, some 26 billion trees have been planted globally. He was so dedicated to tree planting, in fact, that he took an international trip at age 92 to plant a tree in memory of a close personal friend, a former prime minister of Canada. St. Barbe died a few days after accomplishing the purpose of that trip.

“I think people should know about Richard St. Barbe Baker because his legacy still lives on,” says the Foundation’s chief executive, Andy Egan.

“Today we try to walk in St. Barbe’s footsteps,” adds Paul Laird, the Foundation’s programs manager. “We have a sustainable community forestry program, which reaches out and tries to work particularly with groups and local community-based organizations that are close to the real situation—the people themselves doing things for themselves, who understand the threats of land degradation and forest loss, and what that actually means for them.”

From early childhood in England, St. Barbe was attracted to gardening, botany, and forestry. He would run among his family’s trees, saluting them as if they were toy soldiers. Later, as a young man awaiting the start of his university classes in 1912, he took a job as a logger where he lived in Saskatchewan, Canada. He could no longer treat the trees as his friends.

“This area had been virgin forest and one evening, as I surveyed the mass of stricken trees littering the ground, I wondered what would happen when all these fine trees had gone,” St. Barbe wrote at the time. “The felling was wasteful, and I felt sick at heart.”

That experience would be a defining one for St. Barbe. He decided to study forestry at Cambridge University, beginning a lifetime dedicated to global reforestation. Afterward, he moved to British-ruled Kenya, where he set up a tree nursery. While there, he witnessed the effects of centuries of land mismanagement.

Working as a colonial forester, St. Barbe was expected to employ top-down forest management practices. This went against the practices of the indigenous Kikuyu people, who used a traditional method of farming where they burned down trees to create rich soil. St. Barbe wanted to encourage a form of agriculture that promotes the growth of a forest conducive to farming while also protecting the soil from erosion and respecting the culture and wisdom of the local population. The tribal leaders were not open to the planting of new trees, calling this “God’s business.”

To honor the traditions of the Kikuyu people and promote an awareness of their significant role in tree planting and conservation, St. Barbe looked to one of their long-held traditional practices—holding dances to commemorate significant moments. From this integration of cultural values and environmental stewardship was born the Dance of the Trees in 1922.

“So instead of trying to push them and force them into tree planting, he said let’s make this consistent with the culture. So he approached the elders there, discussed it with them and they had this Dance of the Trees which led to the formation of the Men of the Trees,” says Mr. Hanley.

Along with the Men of the Trees’ co-founder, Chief Josiah Njonjo, St. Barbe developed a deeper understanding of the important ecological, social, and economic roles of trees in the life of humanity.

“Behind St. Barbe Baker’s prescience was his deep spiritual conviction about the unity of life,” Charles, the Prince of Wales, writes. “He had listened intently to the indigenous people with whom he worked.”

St. Barbe’s ventures into what is now called social forestry were looked upon with some skepticism. As a colonial forester, he was expected to protect forests that belonged to governments.

“He was extraordinary in that he broke through that,” says Mr. Laird. “He saw that fundamentally these forests belonged to the people of Kenya and you needed to work with the people to conserve the forests.”

This community-led approach remains core to the work of the International Tree Foundation.

“His caring nature for all life is something that really shines through,” says Mr. Egan. “He very much helped to give birth to this idea that it wasn’t just a professional thing about planting trees. It was something that ordinary people in communities could and should be doing. In a way they’re in the best place to actually protect the forests…so their role should be very much recognized and supported and celebrated.”

In researching St. Barbe’s biography, Mr. Hanley discovered that the forester “was definitely very advanced in his thinking. And his whole philosophy of the integration and unity of human society, but also of the natural world, were fairly radical concepts at the time.”

When St. Barbe first encountered the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh in 1924, he found his ideas of nature and humanity confirmed. A Christian with a deep respect for indigenous religious traditions, St. Barbe recognized the truth in Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings about oneness—the oneness of religion, the oneness of humankind, and the interconnectedness of all life. The Faith’s writings also employ imagery from nature to help convey spiritual truths.

“I began to read some translations from the Persian,” St. Barbe wrote, reflecting on his pilgrimage to the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh. “‘In the garden of thy heart plant naught but the rose of love.’ I was enthralled by the sublimity of the language. Here was beauty personified.”

In 1929, while on a mission to establish a branch of the Men of the Trees in the Holy Land, St. Barbe traveled to Haifa to visit Bahá’í sacred sites. Pulling up in his car outside of the home of Shoghi Effendi, St. Barbe was surprised to see the Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith coming out to welcome him and handing him an envelope. It contained a subscription to join the Men of the Trees, making Shoghi Effendi the organization’s first life member.

“He talks about the meeting with the Guardian as the most significant moment in his life, and it really…galvanized him,” says Mr. Hanley.

Through a continued correspondence, Shoghi Effendi encouraged St. Barbe’s efforts. For 12 consecutive years, he sent a message to the World Forestry Charter gatherings, another of St. Barbe’s initiatives, which were attended by ambassadors and dignitaries from scores of countries.

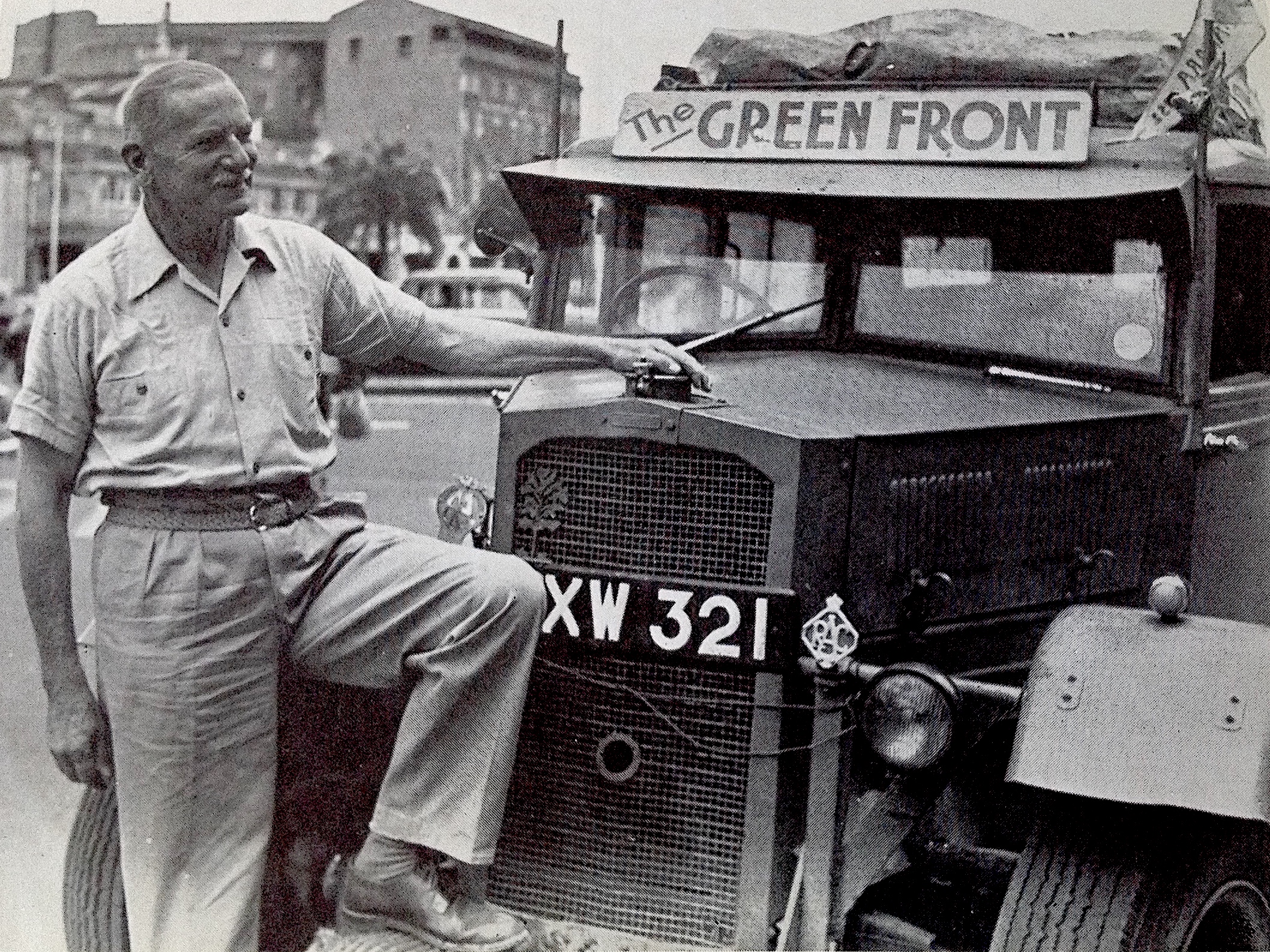

St. Barbe’s work took him to many countries. He was appointed Assistant Conservator of Forests for the southern provinces of Nigeria from 1925 to 1929. He also planned forests on the Gold Coast. In the United States, he launched a “Save The Redwoods” campaign and worked with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to establish the American Civilian Conservation Corps which involved some 6 million young people. After World War II, St. Barbe launched the Green Front Against the Desert to promote reforestation worldwide. One expedition in 1952 and 1953 saw him trek 25,000 miles around the Sahara, leading to a project to reclaim the desert through strategic tree planting. In his late 80s, St. Barbe traveled to Iran to promote a tree planting program. He stopped in Shiraz, the birthplace of the Bahá’í Faith, where he was asked to inspect an ailing citrus tree at the House of the Bab, a place of pilgrimage for Bahá’ís.

The Men of the Trees grew into the first international non-governmental organization working with the environment. By the late 1930s, it had 5,000 members in 108 countries, and its own journal for members, titled Trees.

“Originally it was created because it seemed that St. Barbe just got so many letters and invites and correspondence,” says Nicola Lee Doyle, who today compiles the annual journal. “He was telling people constantly where he was going to be and what he was going to be talking about. So they needed a way to just give everybody the information, and that’s how it started—but then it developed.”

Today, Trees is the world’s longest-running environmental journal.

Successive generations of environmentalists have credited St. Barbe as igniting their passion for their work.

“Sometimes it was the little things he did—like writing an article, or doing a radio interview—that would connect with some youth in some distant country,” says Mr. Hanley. “And several of these people went on to become very significant figures in the environment movement.”

“His legacy is probably related to the fact that he was indefatigable,” Mr. Hanley adds. “It was quite incredible—thousands of interviews, thousands of radio broadcasts, trying to alert people to this idea, and it really did have an impact on the lives of many people who have gone out and protected and planted trees.”

St. Barbe’s pioneering thinking can be particularly valuable now as humanity grapples with the challenges presented by climate change. Indeed, one of humanity’s most pressing challenges is how a growing, rapidly developing, and not yet united global population can live in harmony with the planet and its resources.

“It is now clear that had we heeded the warnings of St. Barbe Baker and other visionaries, we might have avoided a good deal of the environmental crises we face today,” Prince Charles writes. “Richard St. Barbe Baker’s message is as relevant today as it was ninety years ago and I very much hope that it will be heeded.”

Listen to the podcast episode associated with this Bahá’í World News Service story.

In Norte del Cauca, the land is blanketed by sugar cane plantations. They run for miles, under the watchful gaze of the Andes.

Scattered amid the expanse of monoculture fields, villages and small farms dot the terrain. In recent decades, these traditional farms and the lush greenery of the region have been largely overtaken by vast fields of sugar cane crop.

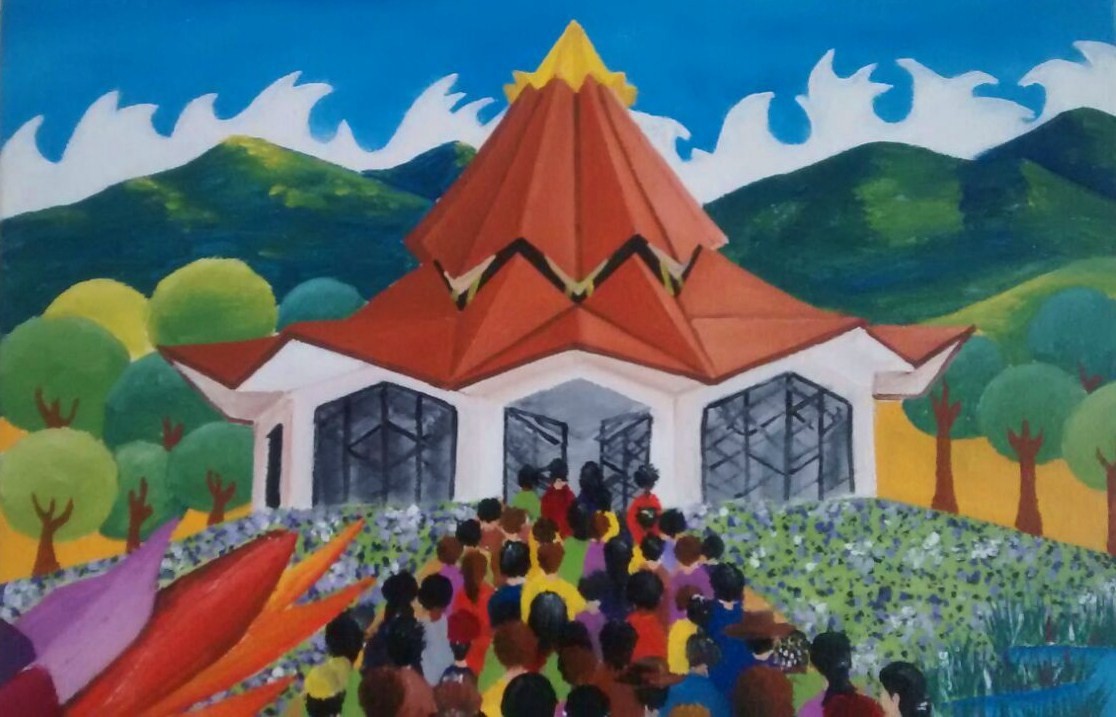

Here, in the village of Agua Azul, and in neighboring communities, people have been talking about the revival of the natural habitat. This conversation was catalyzed in April 2012, when it was announced that a Baha’i House of Worship was to be built here for the people of the region.

Over the period since the announcement, as the community has set out to prepare itself for this momentous development, a heightened consciousness of the nature and purpose of the House of Worship has given rise to an acute awareness about the physical environment and its relationship to the spiritual and social well-being of the population.

“There were several meetings early on, when plans for the Temple were announced,” explains Ximena Osorio, a representative of the Colombian Baha’i community. “People were inspired by the concept of the House of Worship, how it brought together devotion and service, how it was to be a place of worship for everyone.”

“Gradually, conversations arose about the types of trees and flowers that would surround the Temple,” says Ms. Osorio. “They wanted the landscape to capture the beauty and diversity of the region.”

Over time, the conversation evolved. “An idea emerged,” continues Ms. Osorio. “We would grow a native forest on the land surrounding the Temple site. ”

The idea took root, and a team coalesced around the project.

Hernan Zapata, affectionately referred to within the community as “Don Hernan”, recently joined the initiative. A traditional farmer from the neighboring village of Mingo, he has worked the land his entire life.

Today, his is one of the remaining traditional farms in the region, and many of the species which are found on his land have all but disappeared in surrounding areas. His land provides a glimpse into the rich ecological diversity that had characterized Norte del Cauca only decades ago.

“The truth is that Norte del Cauca was once an immense forest,” explains Don Hernan. “But all of that has been destroyed. Now none of it exists.”

“One thing I want with this project,” he explains, “is that new generations should know what once existed. This native forest that we are going to grow should be a school, should be a place of learning.”

The project has captured the imagination of many others in the region as well. Throughout neighboring villages, individuals have begun to donate seeds and plants that can be grown on the land around the Temple site and in a greenhouse that has been built for the project by local volunteers.

Contributions have included indigenous species, such as the rare “Burilico” tree, which is near extinction in the region.

For Gilberto Valencia, a local factory worker and member of the project team, this initiative has connected him to his family history in Norte del Cauca.

“I’ve always been very motivated to know more about the land and about farming because, while I am not a farmer, I come from a long line of farmers. My father and his father always had a farm that they cultivated for the subsistence of the family, and for the sale of goods to others.”

The project inspired Mr. Valencia, who is married and a father, to begin studying environmental engineering.

“When I began working on the land surrounding the House of Worship, I felt at that moment, that the thing that we were going to build was going to change the natural environment,” he said. “This is a chance to change the destiny of the region.”

Mr. Valencia now works on the project alongside his ten year old son, Jason, the project team’s newest and youngest member.

In recent months, Jason has found himself immersed in the project, helping to transplant seeds and saplings to the temple site and working alongside his father to cultivate and protect the surrounding land.

“I have learned about trees I never knew existed,” says Jason, speaking about his experience. “I love working with my father on this project because, together, we’re going to revive many of the plants that have been lost.”

For Alex Hernan Alvarez, a resident of Agua Azul and member of the project team, what is happening in the village has profound implications for the children.

“Here, in Norte del Cauca, we don’t have land or spaces like this, open for everyone. I have three children, and it is very gratifying for me to think that I will leave something for them,” says Mr. Alvarez.

“Knowing that a verdant forest and magnificent House of Worship will bloom for future generations inspires in me a profound sense of dedication.”

Speaking of one of the indigenous trees of the region – the ‘Saman’ tree – Mr. Alvarez states, “The Saman is a traditional tree, beautiful and large. When my children go to the land to pray, they will have a place to sit, under that tree. This motivates me every day. This brings me joy.”

While the House of Worship is not yet built, in many important ways, it is already carrying out its purpose, inspiring the inhabitants of the region to connect with the sacred and reach for greater heights of service to their communities.

“The idea of the Temple, what it represents,” says Ms. Osorio, “is in itself cultivating in all of us – children, youth and adults – an appreciation for the importance of a life centered around worship of God and service to humanity.”