In 1856, or thereabouts, even as the little city of Yazd, in the very heart of Persia, was carrying on its lackluster existence, something was astir. The town’s population for the most part lived in poverty and ignorance, unaware of what was happening in the rest of the world. But there was something stirring. There was hushed talk of the Báb, the new Prophet Who had been martyred, and of the Message He had brought. There were people secretly spreading the news at the risk of their lives.

A youth, only fourteen, came into contact with these people, heard the Message and wholeheartedly accepted it. Only fourteen years of age! His name was Shaykh ’Alí. He was the eldest son of the well-to-do and highly respected Hájí ‘Abdu’r-Rahím Yazdí. The family was alarmed. The boy was in grave danger. His allegiance could bring ruin to the whole family. But Shaykh ’Alí was ablaze. To distract him from the Bábí Faith, his family sent him to Kirmán with enough goods to start a business. The shop was successful but soon rumors floated back that he was meeting with the Bábís. ‘Abdu’r-Rahmín went to Kirmán and brought him home.

In Yazd the boy again attended the secret meetings and took aid to the beleaguered Bábís who were imprisoned there. One night he was so late returning home that his mother, terribly worried, waited for him at the door and when he came in, slapped him, without saying a word. In silence he took her hand, kissed it tenderly, and gazed at her with deep love.

Throughout this difficult time, in the face of the calumnies and persecutions heaped upon the Bábís by their enemies, Shaykh ’Alí displayed a kindness and fearlessness remarkable in one so young. As time passed, his character, his behavior, his attitude and his actions gradually won over the whole family. One by one they joined the Faith. Now meetings were held in the Yazdí home though the need for secrecy remained paramount. Teachers came from other cities, each with new tales. Some who came from Baghdád spoke of Bahá’u’lláh. Later they came from Adrianople, and then from ‘Akká.

My father, Hájí Muhammad, who like his brother had joined the Faith when he was fourteen, left for the Holy Land with a friend, a donkey, lots of faith and very little money. He and his companion set out to see Bahá’u’lláh and traveled over steep, rugged mountains and across hot, arid plains until they arrived in ‘Akká, around 1870. Other members of the family followed later. Hájí ‘Abdu’r-Rahím, my grandfather, left Yazd after he had been tortured, beaten and bastinadoed. The story of this ‘precious soul’, as the Master called him, his arrival in ‘Akká, and his life there, is told with tender compassion by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Memorials of the Faithful. Each member of the Yazdí family was given an assignment by Bahá’u’lláh and sent out to accomplish it. Hájí Muhammad, my father, and two other youthful believers were sent to Egypt where they worked hard for many years and eventually built up a prosperous business.

Through these believers – all young people – the Faith was first established in Alexandria, Cairo and Port Said. Although they were not free to openly teach the Faith they were on good terms with the population and were generally well-liked and respected.

My family and I lived in a suburb of Alexandria called Ramleh, a beautiful and peaceful residential district on the edge of the Mediterranean. The house in which I was born and where I lived until I was about four or five, had a separate guest house and a large garden surrounded by a wall of rough-hewn stone. Within the garden there were many lime, sweet lemon, orange and pomegranate trees as well as rose bushes. In the summer a tropical scent hung in the air. The house to which we then moved also had a large garden. Jasmine grew over the veranda, a large porch adjoining the garden. Here our family often had breakfast, with father presiding at the samovar and dispensing glasses of hot tea to the adults and, to the children, hot water with a drop of tea floating on top. Before breakfast, however, we chanted our morning prayers and heard father tell wonderful stories about his experiences with Bahá’u’lláh and the Master, or read the latest communications from the Holy Land.

It was in this setting, when I was a child of eleven, that I heard the news of the coming of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to Ramleh. The news came suddenly, without warning. The Master had left Haifa without notice on a steamer bound for Europe. Because of ill health and fatigue, He had stopped in Port Said and was coming on to Alexandria. Then the news came that He was coming to Ramleh! To Ramleh where we lived! What a miracle! There was intense joy within the Bahá’í community, within my family, within me. Of all the places in the world, He happened to choose Ramleh as His headquarters for His trips to Europe and America during the period 1910-1913. Excitement, curiosity, anticipation swirled through my mind. All I knew about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was what my father had told us. No one in the immediate family except father and grandfather had seen Him. The only photograph was an early one taken when He was a young man in Adrianople. He was a prisoner beyond our reach, a legendary figure. Now He was free and coming to Ramleh! The Bahá’í Faith was an integral part of me, not something superimposed. In Ramleh I was surrounded by it, lived it, believed it, cherished its spiritual concepts and goals and principles. I realized its fundamental importance, its necessity for the world today. Yet my studies at the French school which I attended had opened other areas to my mind. The discoveries of science fascinated me and I believed they provided us with effective tools for the implementation of the teachings of the Faith. I prayed that I might be guided to play some role in this endeavour. I sensed that my contact with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would provide the inspiration and the impetus to move in this direction. So I waited eagerly for the day of His arrival.

There was a crowd gathered in front of the Hotel Victoria. Suddenly there was a hush, a stillness, and I knew that He had come. I looked. There He was! He walked through the crowd – slowly, majestically, smiling radiantly as He greeted the bowed heads on either side. I could only get a vague impression as I could not get near Him. The sound of the wind and surf from the nearby shore drowned out His voice so I could hardly hear Him. Nevertheless, I went away happy.

A few days later, a villa was rented for the Master and His family, not far from the Hotel Victoria, in a lovely residential section that lay right next to the beautiful Mediterranean and the beaches. Like all the villas in that area, it had a garden with blossoms and flowering shrubs. It was there that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá chose to receive His guests – a great variety of notables, public figures, clerics, aristocrats, writers as well as poor and despairing people. I went there often, sometimes on the way home from school, sometimes on weekends. When I was not in school I spent most of my time in His time in His garden. I would wait to catch a glimpse of Him as He came out for His customary walk, or conversed with pilgrims from faraway places. To hear His vibrant and melodious voice ringing in the open air, to see Him, somehow exhilarated me and gave me hope. Quite often, He came to me and smiled and talked. There was a radiance about Him, an almost unlimited kindness and love that shone from Him. Seeing Him, I was infused with a feeling of goodness. I felt humble and, at the same time, exceedingly happy.

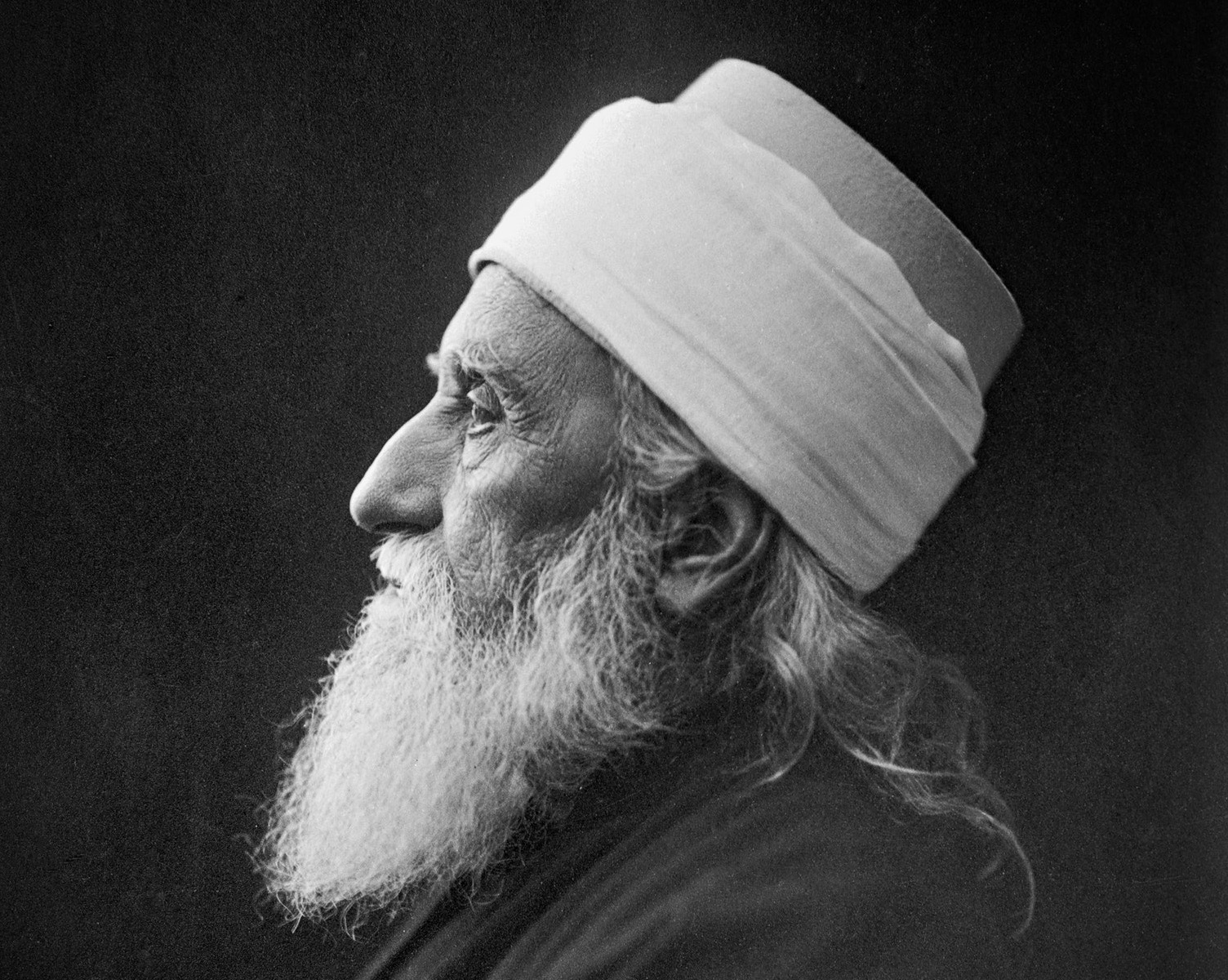

I had many opportunities to see the Master – as we always called Him – at meetings and on festive occasions. I especially remember the first time He came to our house to address a large gathering of believers. The friends were all gathered, talking happily, waiting. Suddenly all grew quiet. From outside, before He entered the room, I could hear the voice of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, very resonant, very beautiful. Then He swept in, with His robe flowing! He was straight as an arrow. His head was thrown back. His silver-gray hair fell in waves to His shoulders. His beard was white; His eyes were keen; His forehead, broad. He wore a white turban around an ivory-colored felt cap.

He looked at everyone, smiled and welcomed all with Khushámadíd!Khushámadíd! (Welcome! Welcome!) I had been taught that in the presence of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, I should sit or stand with my hands crossed in front of me, and look down. I was so anxious to see Him that I found myself looking up furtively now and then. He often spoke – I was privileged to hear Him speak on many subjects. For nine months it seemed like paradise. Then He left us and sailed for Europe. How dismal everything became. But there was school and there were duties. Exciting news came from Europe, and there were memories! ‘Abdu’l-Bahá came back four months later. Paradise returned. He spoke to me on several occasions, calling me Shaykh ’Alí, the name He Himself had given me, after my uncle who was the first member of the family to join the Faith. When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá spoke to me, I would look into His eyes – blue, smiling and full of love.

Again He left us, this time for America. I will never forget the scene of His departure as He came out of the house and turned to wave gazing down from the veranda above. They were greatly concerned about His safety and well-being. He was sixty-eight years old. He had suffered many hardships and endured severe trials. He had been in prison for forty years of His life and now He was undertaking this journey to a far-off country utterly different from any to which He was accustomed. But ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had made up His mind and nothing could turn Him back. He walked out of the garden gate and never looked back again. He walked for several blocks near the shore to take the electric train to Alexandria where He would board the ship that was to take Him to New York. He was followed by about thirty believers who walked silently behind Him. I was one of them. What ‘Abdu’l-Bahá accomplished in America is now history. He went to Europe and came back to Ramleh on 3 July 1913, to remain until the following December. Then He left for Haifa, never to return.

That was the first chapter of my experience with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá when I was a child between the ages of eleven and fourteen. In 1914 my family moved to Beirut, Lebanon, only a short distance north of Haifa. This opened the second chapter when I was privileged to be in the presence of the Master again, but only on special occasions. I was at that time a student at the American University of Beirut, then known as the Syrian Protestant College. In the summer of 1917 I spent my summer vacation with my uncle, Mírzá Husayn Yazdí, in his house on Mt. Carmel, a memorable two months for me. Every evening before sunset I had the bounty of being in the presence of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. I would join the other believers gathered in front of the Master’s house. The entrance had an iron gate and then a garden. He would come out with a cheerful and warm greeting, welcome all, and take His seat on the platform at the head of the wide stairs. The sun was going down, and it was very quiet. Sometimes He sat in a relaxed attitude and didn’t speak at all. Usually, however, He spoke. He talked in His commanding voice, looking straight ahead, as if He were addressing posterity. He talked about Bahá’u’lláh, about His Teachings, and about significant world events in the history of the Faith. He told stories sprinkled with humour. Often, however, He talked of the believers around the world and of their progress in spreading the Faith. Then He would become wistful. For three years, while World War I raged, He had little news from abroad. The isolation and constraint weighed heavily upon Him. Now and then He would address individuals in the audience, ask them about their families, their work, their problems; He would offer advice and help. Toward the end, He would ask one of the believers to chant verses from the poems of Bahá’u’lláh. When the chanting ended, the meeting was over. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would arise and enter the house. Dusk would have descended over Haifa.

There were frequent visits to the Shrine of the Báb. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would ride the old horse-drawn, bus-like vehicle up the mountain. The rest of us would walk along the rocky road, past the Pilgrim House, to the terrace overlooking the city of Haifa, the blue bay beyond and, in the distance, the hazy outline of ‘Akká. We would gather there until ‘Abdu’l-Bahá appeared and entered the Shrine. He would chant the Tablet of Visitation. Sometimes He asked Shoghi Effendi to chant this prayer. And when it was all over and the believers began to leave the Shrine, He would stand at the door with a bottle of rose water and put a little in each one’s hand. There were also trips – less frequent – to ‘Akká and Bahjí, and visits to the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh. There were also times that summer when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá went in the horse-drawn carriage to Tiberias, Lake Tiberias and the Sea of Galilee, of Biblical renown. His purpose on these trips was to oversee the grain crops which the believers, under His supervision, had planted in the Jordan Valley. The grain the Master had stored in ancient Roman pits was to be distributed to everyone who needed it, Bahá’í and non-Bahá’í alike. On 27 April 1920, in the garden of the Military Governor of Haifa, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was invested with the insignia of the Knighthood of the British Empire in recognition of His humanitarian work during the war for the relief of distress and famine.

I would sometimes go into ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s garden and talk with Ismá’íl Áqá, the gardener, an old man beloved by the Master. On one of’ my visits to the Master’s garden I noticed that everyone was quiet. When I asked why, I was told that a commission of inquiry was interrogating ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in His room. I could hear ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s clear, commanding voice through the open window above our heads. He spoke to the members of the commission with dignity and authority as if He were the investigator and they the suspected culprits.

Although He was humble in many ways, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá never really bowed to anyone; at the right time, and in the right way, He was proud. He would not compromise the Cause of God. Somehow, the confidence with which the Master spoke gave me confidence and faith that He would be spared. Those were dangerous and difficult days. The violators were active and Jamál Páshá had vowed that he would crucify ‘Abdu’l-Bahá when he returned victorious from his campaigns. When he did return, however, he was fleeing in defeat and humiliation. Despite the turbulence of this period the Master conferred upon the Bahá’ís of the west their world mission by revealing the Tablets of the Divine Plan, eight in 1916 and six in 1917.

I remember other little details from the summer of 1917, such as eating at ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s table. He ate very simply, but He insisted on others having the proper amount of food. Quite often He would come behind the guests and speak to them. I remember His standing behind my chair saying, ‘Why aren’t you eating?’ I was hungry, but my shyness prevented my eating. ‘Why aren’t you eating, Shaykh ’Alí?’ And He placed a generous portion of rice on my plate. I had to eat it! One day, when I was walking along a curved street up the hill toward the House of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, I turned the corner and there He was!

I saw the Master walking down the hill, followed by two of the believers. As was the custom, I stepped to one side and bowed. The Master stopped and walked over to me, stopped right in front of me, and looked me straight in the eyes. I shall never forget having seen ‘Abdu’l-Bahá face to face.

What was He like? His bearing was majestic, and yet He was genial. He was full of contrasts: dominant, yet humble; strong, yet tender; loving and affectionate, yet He could be very stern. He was intensely human, most keenly alive to the joys and sorrows of this life. There was no one who felt more acutely than He did the sufferings of humanity.

At the end of the summer I went to see my family in Damascus before going back to college to graduate. Then I returned home. The war seemed to drag on and on, but finally the end came. Our great concern was Haifa: what had happened there? But soon the news arrived: General Allenby and the British had occupied Haifa and the Master was safe. As the doors to the outside world opened again we began to make plans. There was much thinking and counting of pennies. I had studied civil engineering and had been hired as a draftsman by the government. From my earnings I had saved a little, but it wasn’t enough to enable me to go on with my graduate studies. News of this reached ‘Abdu’l-Bahá through my uncle, Mirza Husayn, and the Master offered me one hundred pounds which, in those days, was the equivalent of about $500.00. That made it possible for me to go. I wasted no time. In the autumn of 1919 I went to Haifa in order to say farewell to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. I was on my way to Europe – Switzerland and then Germany – for my graduate studies. I was twenty years old. This was to be my last experience with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

I was in Haifa for two or three days. Just before I left ‘Abdu’l-Bahá called me to His room. I was there alone with Him; the only other person was Shoghi Effendi, who was in and out. The Master invited me to be seated and He asked Shoghi Effendi to bring me some tea. He spoke to me, gave me instructions on how to live, mentioned that He had hopes for me. He said, ‘You are a good boy, Shaykh ’Alí. The tea that Shoghi Effendi brought in a glass was boiling hot. I tried to drink it, but couldn’t. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said, ‘Drink! Drink your tea!’ So I had to drink it! It didn’t matter! At the very end He gave me His blessing. Then He stood up and beckoned me to Him. I went to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and He put His arms around me and kissed me on both cheeks. I never saw Him again.

Two years later, when I was at the University of California studying civil engineering, I learned of‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s ascension. Looking back, I can see that the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá marked the end of an era. He was passionately devoted to the single goal of spreading the Teachings of Bahá’u’lláh. It was His mission to establish the brotherhood of man on earth in fact, as well as in principle. Nothing stopped Him; nothing deflected Him from His purpose. And yet it was not easy, for despite His high station, He was also intensely human, and He suffered a great deal. He was often very happy, and He always asked the Bahá’ís to be happy. Be happy! Be happy! That was His counsel to the believers, and He set the example. But there were times when I would see Him with the burdens of the whole world upon His shoulders.

There is something I learned from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá which I feel should not be forgotten. His life was not really His life alone; it was the life of every one of us. It was an example for every one of us. A new generation of Bahá’ís is being attracted to the Faith, and a new generation is growing up within the Bahá’í community. They will acquire knowledge of the Faith from books. But this is a living Faith. The Manifestation of God has appeared and initiated a new era. Bahá’ís have lived and worked and died for this Cause. The Faith is not something extraneous; it is not merely something beautiful, logical, just and fair – it is the very blood and fibre of our being, our very life. If men and women all over the world were to arise in ever-increasing numbers and make ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s way of life their own, each pursuing His path with zest and confidence, what would the world be like? Would not these individuals be a new race of men?