“If you had your life to live all over again, what would you change?”

This question was put to Bernard Leach during the last year of his life. His instantaneous reply: “Nothing, except myself, I hope.”

“A change for the better?”

“Of course. Deeper, wider, truer, more loving. When I went into hospital nine years ago and very nearly died, what did I learn? That I had never been as kind as those who were kind to me. And I felt shame at myself for not having been more thoughtful, more kind, more generous. It did make a difference.”

The interview was for a “Profile” of Bernard Leach C.H., C.B.E. for the overseas service of the British Broadcasting Corporation which was broadcast to over forty countries.

Many times I have been asked what I remember most about Bernard Leach: it was his humility. He used to say, pointing his long finger upwards, “It’s the ‘I’, not the I.”

I remember vividly his miraculous recovery from that serious illness in 1969. The doctors and the specialist did not expect him to live. He was eighty-three. But those Bahá’ís who were close to him at the time had no doubts. This was a spiritual progression. There was even a Bahá’í nurse who had just arrived at the hospital to take part of her training. I was committed to a demanding job that weekend in August. I knew he was gasping for breath with the help of oxygen. My prayers took me to the typewriter. “You are suffering like the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh for the love of God because He has great things for you to do. Be content with the love of God. Everyone, everywhere is praying for you and willing you to get better.” This message I sent in large type, to be read to him by a very dear friend. I was told that he changed colour afterwards. In the evening I received the wording of a cable from the Universal House of Justice assuring Bernard of loving prayers. Early the next morning I was allowed into his hospital room for the few minutes I needed.

“I’ve been very ill,” he said between gasps for breath.

“I know,” I said. “Don’t talk, listen.” I placed my hand on his shoulder. “Everyone is praying for you on Mount Carmel. They are praying at the Holy Shrines for your recovery.” Then I left him, knowing that he would draw comfort from the thought of those prayers. About a week or so later when I visited him he showed me the following lines that he had written:

Oh, let me out

Into the garden there

I want to put down

My shrunken hand

To the green grass

Yet once again

Before I lie quiet

Under the sod.

Many voices rose gently

To Him, the Lord God,

Who looked down in mercy

And said, `Spare the rod.’

In this room

Where I have known

Such pain and joy

I felt the tremor

Of those prayers

All the way from

Here to Carmel.

O God, wilt Thou

Accept my thanks

From here to Heaven?

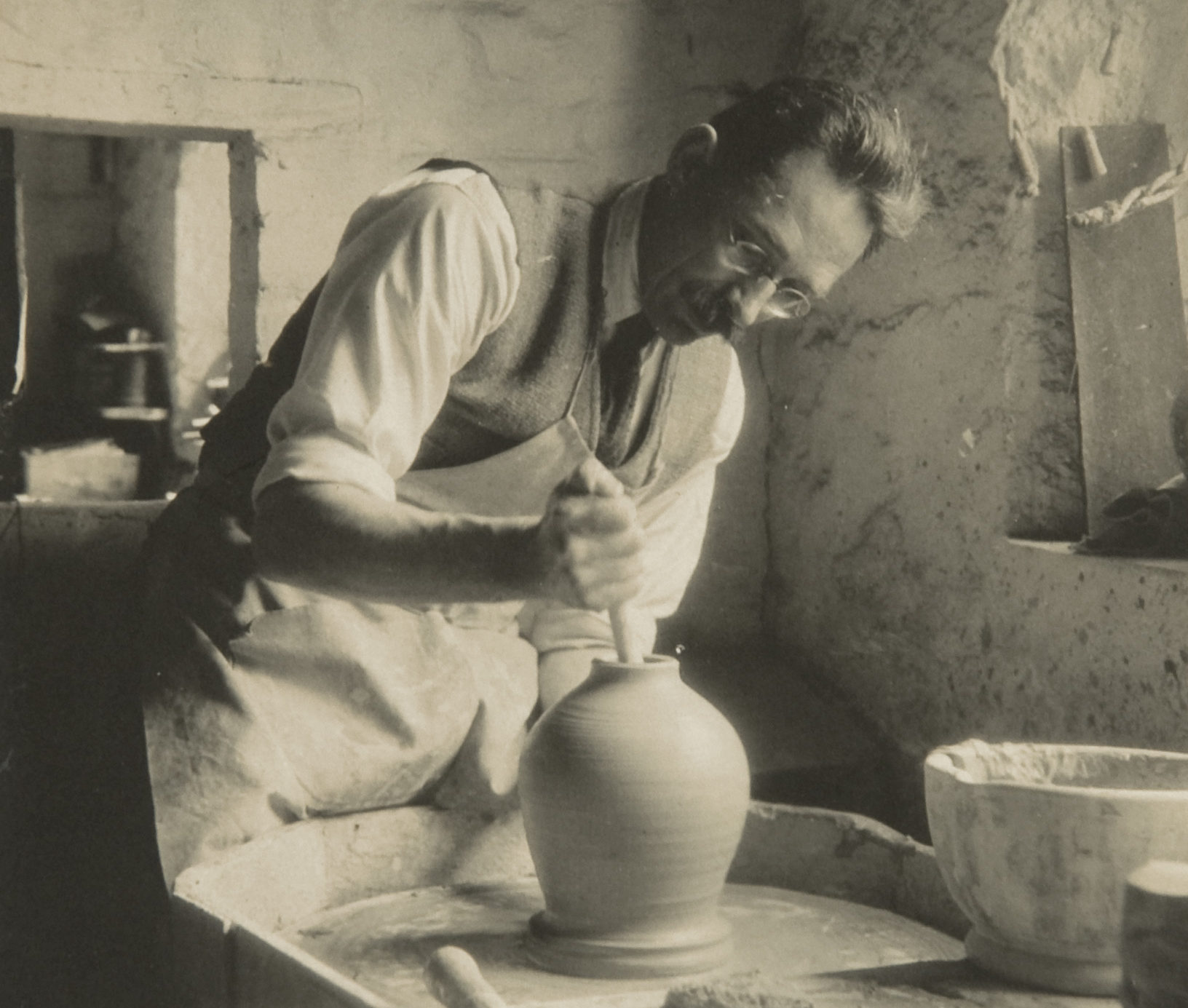

When Bernard Leach was born in Hong Kong in 1887 his mother died, and he was taken by his grandparents to live with them in Kyoto where his grandfather was a professor of English at the university. Bernard was educated in England, and at the Slade School of Art in London he met his life-long friend, Reginald Turvey whom the Guardian later referred to as “the spiritual father of the Bahá’ís of South Africa”. When Bernard returned to Japan in 1909 with the first etching press ever to reach that country (he planned to make a living teaching etching) he wanted to find out more about Eastern art and life. He speaks of his experience in 1911 when he met a group of artists and poets and first saw pots being made. ‘One was taken out from the kiln, red hot, with long-handled tongs, dipped into a bucket of cold water, and it did not break. I thought, “Isn’t it exciting! I want to do that; I believe I could learn to do that. I wonder if I could get a teacher? I did…”

Before he left Japan in 1920 some of his friends presented him with a book entitled An English Artist in Japan. The prophetic tribute written by Soetsu Yanagi, the founder of the Japanese Craft Movement, concludes with these words:

When he leaves us we shall have lost the one man who knows Japan on its spiritual side. I feel very sad that he is going, but I hope when he returns to his own land he will be able to represent the East in a more just way than has yet been done, and that not only in words will he be able to show his affection, but in his works. I consider his position in Japan, and also his mission in his own country, to be pregnant with the deepest meaning. He is trying to knit the East and West together by art, and it seems likely that he will be remembered as the first to accomplish as an artist what for so long mankind has been dreaming of bringing about…

“I desire distinction for you…” were the words of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá addressed to the Bahá’ís.

Fifty years after Bernard Leach left Japan he was honoured by the World Crafts Council at a gathering in Dublin. In 1974 he received the Japan Foundation Cultural Award; he had already been given, in 1966, the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Second Class, the highest honour the Japanese government bestows upon a foreigner. He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1962 and, in 1973, in an audience with Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth at Buckingham Palace, he was made a Companion of Honour.

During these later years retrospective exhibitions of his work were held both in Japan (1966) and in England (1977). During the opening week of his exhibition in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum printed invitations were made available to visitors for a Bahá’í talk given by him at the Commonwealth Institute on `My life, my work and my belief’. Many people attended that meeting and mention of the Bahá’í Faith was made in some of the press reports.

These years also saw the publication of several books written by Bernard Leach including Drawings, Verse and Belief in 1973 and, in 1978, Beyond East and West, which he considered to be his most important literary work. This book, the last two chapters of which are devoted to the Faith–“The Mountain of God” and “Stepping Stones of Belief”–was also published in America and has been translated into Japanese. Many seeds must have been and still are being sown through this testament of faith. Reviews of Beyond East and West in many countries mentioned his Bahá’í belief and paid tribute to him. The reviewer of the Birmingham Post wrote:

I have never met Bernard Leach… I feel that, having seen this last exhibition and having enjoyed every page of this enlightening and loving book, and having as it were travelled with him through time, sharing his feelings and experiences and friendships, I now already do know, and intimately, this great man, respected and indeed honoured all the world over… It is a book to be delighted in, not just by potters such as Leach himself, or even by artists and craftsmen in general, but by anyone who cares about the joy of the one life we all share–all roads meeting, as we are reminded, on the mountain of God…

It was not possible for Bernard in his book of memoirs to include all his Bahá’í activities over the years. Wherever he travelled he tried to keep some time for talks on the Faith. While exhibiting in South America–in Caracas and Bogota–he was tendered a special reception in Colombia to which several Bahá’ís were invited. His pamphlet, My Religious Faith, written in Japan in 1953, has been translated into Japanese and is still being used. A copy was presented to Princess Chichibu by Amatu’l-Bahá Rúhíyyih Khánum when she visited her while touring Japan in 1978. The blindness which came to Bernard in 1974 opened another door. On 30 December 1973 he scrawled with a thick pen:

Come blindness

With the dawn this day.

Not to see a human face again.

Not to see a line on paper drawn.

Warning, yes, but both this day.

Groping along walls,

Premonitory steps.

Awake, awake, the inner eyes,

Love more, not less,

The memories of human sight,

See with, not through.

The spiritual awareness which grew with his blindness was an inspiration to visitors who came from far and wide to see him. He talked much about the Faith. One potter declared her belief in Bahá’u’lláh upon returning to America after spending a few days with him in St. Ives, Cornwall.

It was important to him to leave this world with all work done. “Death as a friend, death as a doorway”, he wrote to a Bahá’í friend after completing his manuscript of Beyond East and West. It was a long time since 1914 when he had first heard of the Bahá’í Faith from Agnes Alexander in Japan and, in that same year, had written:

I have seen a vision of the marriage of East and West, and far off down the Halls of Time I heard the echo of a child-like Voice: “How long? How long?”