It is late morning in the New Zealand town of Masterton. Dame Robin White DNZM1The Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (DNZM) is a prestigious honor awarded in New Zealand to individuals who have made significant contributions to the nation in fields such as arts, science, business, or public service. Recipients are granted the title Dame and recognized for their distinguished achievements.—a painter and printmaker known for her vibrant explorations of Pacific life—settles into conversation with her longtime friend and collaborator, Tongan artist and curator Ruha Fifita. Ruha is visiting for a few days, and they sit together in Robin’s studio. Holding cups of tea and surrounded by an array of drawings and colorful works in progress, they reflect on years of working together and the many insights that their collaboration with each other and many others has yielded.

For much of her early career, Robin was recognized in New Zealand for her bold, light-infused portraits and landscapes, a style that connected her, in the public eye, to the so-called Pacific Realist painters of the 1970s. Yet even in those early, seemingly solitary works, a communal spirit peeks through. In later decades, after living for a time in Kiribati, her art would become profoundly collaborative, engaging partners from a range of backgrounds and homelands.

One of Robin’s significant partnerships over the past decade has been with Ruha. From their initial conversations in Tonga about how Robin could expand on her recent experiences working with barkcloth practitioners in Fiji, the two developed an evolving partnership in which they have explored themes such as customary and contemporary approaches to art and how a vision of humanity’s oneness informs and illuminates creative work.

Below is an interview with Robin and Ruha, shaped and edited from two transcribed audio recordings. The conversation that unfolds explores how, as Bahá’ís, their journey in the arts has been fundamentally shaped by the oneness of humankind—the cardinal principle of the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh.

Interview

INTERVIEWER: Let’s begin with the idea of collaboration. You both frequently highlight the term, yet “collaboration” can mean many things. What does it mean in your practice?

ROBIN: On a very basic level it means seeking the opportunity to work with others in order to achieve something that I could never do on my own. So, there are circumstances in which collaboration is a practical necessity. For example, the making of a large ngatu2Ngatu is a traditional barkcloth made in Tonga from the inner bark of the paper mulberry tree (Broussonetia papyrifera). It is created by beating, layering, and decorating the bark with natural dyes and patterns. It is highly valued in Tongan culture and is used for special ceremonies, gifts, and decoration. demands a wide range of skills and requires teamwork for its completion. Plus, it can be a very enjoyable and sociable experience—making friends, telling stories, sharing food. It’s fun.

Over time I find that there is much to learn, at a deeper level, about what collaboration can mean. I find it a liberating experience, liberating from the confines of self, and something that offers a wide-open horizon of possibilities.

Of course, collaborating is not without risks and challenges, but that’s also part of the appeal. When we come from different backgrounds—culturally, generationally, or in terms of craft—it’s vital to spend time creating a shared understanding. We ask: “Why are we doing this?” and “What do we hope to achieve beyond the finished artwork?”

When a deeper sense of unity is fostered—when people talk freely and openly about their motivations and ideas and feel they are part of the decision-making process—problems that arise can be solved. I’ve also seen what can happen when a collaborative project loses track of the ultimate purpose. But when we remember the principle of the oneness of humankind and reflect on our coming together to learn from each other, the process becomes infinitely enriching.

RUHA: I feel very fortunate to have spent the formative years of my life immersed in environments strongly characterized by a spirit of cooperation and reciprocity. This spirit is present in the Bahá’í community and in the cultures of the Pacific. Spending most of my upbringing in Tonga meant that the opportunities to observe and contribute to rich experiences of collaboration were many and integral to the way one participates in family and community life, and that is really what shaped my engagement with the arts from the very beginning.

We learn dances to contribute to significant occasions. We learn to paint and make things from natural resources around us. We learn to create dance costumes and gifts. We raise funds for community and family initiatives. As we gain experience and skill, we embrace opportunities to teach, help, and shape opportunities for others.

This context also allowed me and my family and friends to connect and work with many other creatives from our region with similar arts practices.

I guess, this is to say that my foundational experiences have been ones where collaboration is assumed, shared authorship is the norm, and the complexity of this way of working is nurtured and supported by collective core values and longstanding cooperative relationships. Trying to make or share work in more Western contexts has sparked an interest in how others view collaboration.

I love the way the artist Pablo Helguera3Pablo Helguera is a Mexican-American artist, educator, and writer known for his work in socially engaged art, performance, and museum education. His projects often explore history, language, and community engagement, with notable works like The School of Panamerican Unrest. He has held key roles in major institutions such as MoMA and the Guggenheim, contributing to the dialogue between art, education, and social change. has described the different layers of participation in collaborative creative processes:

Nominal—that is offering encouragement, food, prayers, space to work; or Discursive—for example, contributing conversation, stories and/or insights that shape the conceptual scope and content of the work; or Directed—offering a skill and time to complete a specific task; or Creative—offering creative agency to a specific part of the work to achieve a defined outcome; and finally, Collaborative—which I now define as contributing to shaping the purpose, function, and form of the work and participating fully in decision-making processes throughout its completion.

It’s important to develop language that helps us describe the nuances and complexities of the term “collaboration” so that its meaning is not lost, as it is used to refer to many things. My contribution to projects with Robin has floated between these different layers.

INTERVIEWER: You both mention spiritual principles. In your view, how do central Bahá’í teachings such as the oneness of humankind shape the day-to-day reality of making art together?

ROBIN: It’s foundational. I think of humanity as being like one family—so if I’m working with an artist from Tonga, Fiji, or Kiribati, I begin with the conviction that our shared spiritual reality outweighs any cultural differences.

We do have differences, of course, but I don’t see them as a barrier. Instead, they’re a richly varied resource of perspectives. I like thinking of it as working in the space between. It’s a space that is dynamic and creative, and these are conditions that rely on contrast or diversity. If everything is predictably the same then where is the energy? So, I really welcome opportunities to work with others who come from a very different background and life-experience. It’s energizing and full of opportunities to learn from each other.

Another related concept is work as worship.4‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the eldest son and appointed Successor of Bahá’u’lláh, wrote that “work done in the spirit of service is the highest form of worship.” (‘Abdu’l-Bahá on Divine Philosophy, p. 78). If we see our work—our making, weaving, painting—as an act of devotion carried out in a spirit of service, then that feeling of reverence becomes part of every stage of what we do. We each bring a certain attentiveness, a certain respect, to the materials, the process, and the people involved.

RUHA: Looking back, I do feel it was two concepts central to being a Bahá’í—the oneness of mankind and the importance of living a life of service to others—that shaped my first engagements with Robin.

INTERVIEWER: How did you begin your first big collaboration?

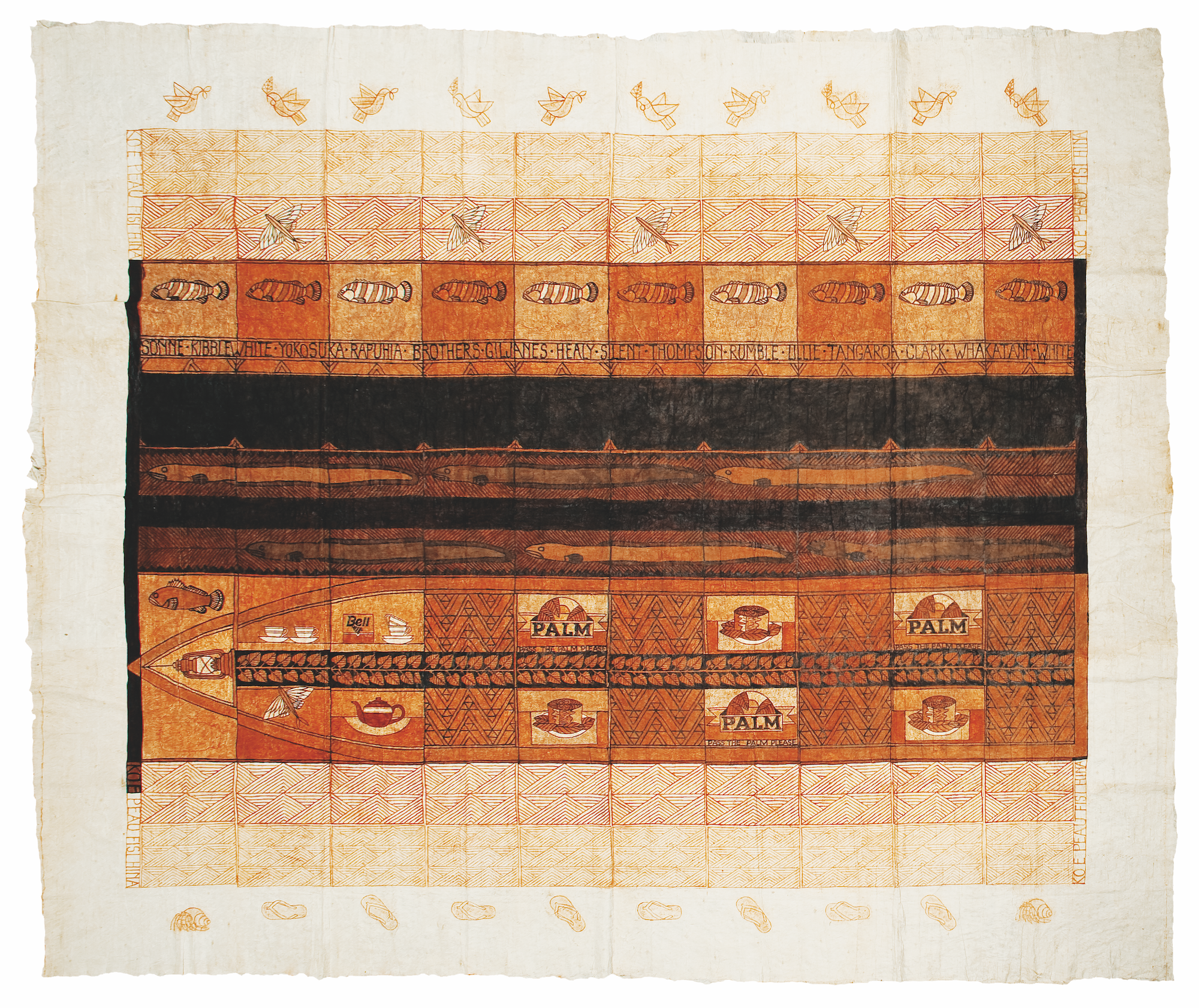

RUHA: Robin arrived in Tonga after visiting the Kermadec Islands5A remote oceanic area northeast of New Zealand, including the uninhabited Kermadec Islands and the deep Kermadec Trench. Known for its rich marine biodiversity and volcanic activity, it is a key site for conservation efforts. wanting to learn about traditional ngatu-making. She had started to think about how to use this medium as a way of responding to her time in the Kermadecs, which lie in the ocean space between Tonga and New Zealand.

Typically, a Tongan kokaʻanga group—a collective of women making ngatu—will work on a piece together, but that group might not be familiar with Western art world contexts. Initially, Robin asked me to help find an experienced group. In the process, we discovered we had a shared framework for discussing both the form and meaning of the work. I was then invited to help make the work she needed to complete for an upcoming exhibition in New Zealand.

Over the next few months, I contributed to the project as someone to bounce ideas with, to help her source the necessary materials, to connect with local practitioners and community leaders, and to help paint the final work. I felt fortunate to be part of conversations that explored the aims of the piece and how its intended message could guide decisions about pattern, scale, color, and whom to involve. I had not had many interactions before that with professional artists that were contributing to global discourses through work shown in art galleries, and I was grateful to be able to learn from her experience.

ROBIN: I remember being so grateful for Ruha’s youthful energy, her cultural curiosity, and her readiness to learn. She might say she was new to some aspects of barkcloth production, but she had a closeness to it that I lacked. Also, because we share the same spiritual convictions, there was a sense of confidence in the way we worked together and I could trust that if either of us thought that something needed to change, or if we had to consult with village elders, we’d do so in a spirit of humility.

That first big work we made, Siu i Moana, was about the concept of reciprocity. The Kermadec Islands that I had just visited lay at a halfway point between Tonga and New Zealand. So, I started thinking about how to visually represent the constant exchange and movement of people and goods between those two countries as a metaphor for the sharing of ideas and values whereby both populations are enriched.

INTERVIEWER: You’ve both touched on bridging traditional and contemporary in your work. Would you say your art preserves an old form, or is it something else?

ROBIN: I don’t see it primarily as preservation. Ngatu is a living art form, integral to Tongan life. It doesn’t need reviving or preservation.

What we do with ngatu, or with Fijian masi6Masi is a traditional Fijian barkcloth made from the inner bark of the paper mulberry tree (Broussonetia papyrifera). It is handcrafted through a process of soaking, beating, and layering the bark into large sheets, which are then decorated with natural dyes in intricate geometric patterns. Used in ceremonies, clothing, and gifts, masi holds deep cultural significance in Fijian society, symbolizing respect, identity, and tradition., is explore ways in which these traditional forms can have an ongoing role in telling contemporary stories.

RUHA: I often find the image of a sapling comes to mind when thinking about my own engagement with cultural practices. Planted in the rich fertile soil of culture prepared by our ancestors, I feel the responsibility of the seeds of each new generation is to ensure that our roots continue to grow and draw from ever-deepening understandings of this cultural knowledge, while, at the same time, striving to respond to the needs and changing reality of the world around us.

I personally feel like a very small plant in this regard, grateful to have many strong plants around me helping to create the conditions for that growth. The ecology is enriched by every effort. So, it’s less about building a bridge than learning how engagement in this practice can enrich the conditions that support the array of efforts being made across different fields of endeavor to ensure the world we are building is benefitting as much as possible from the instruments and knowledge generated by those who came before us.

INTERVIEWER: When artists from outside an indigenous community engage in that community’s art forms, it can raise concerns about cultural appropriation? How do you respond to such concerns?

ROBIN: When I first began working with Kiribati weavers, and later with Tongan or Fijian craftspeople, some people assumed I was simply borrowing a tradition for my own gain. But we approached the process differently, through friendship, building real relationships, learning from local knowledge-holders, and approaching our work in a humble posture of learning. In the end, I have to examine the integrity of my own motives for the work that I am doing. The way forward for me is always to be mindful and clear on what my purpose is and on the core principles that determine how I proceed.

I also want to clarify that appropriation typically implies exploitation—a circumstance in which someone with more power or status takes something from a vulnerable individual or group. But these island communities are not powerless. To think that way is patronizing.

I begin with the conviction that indigenous people have agency, that is, capacity and control of their own lives, thoughts, and behavior, and the ability to handle a wide range of tasks and situations.

Yes, there has been colonialism with its attendant exploitative behaviors, and remnants of those patterns still exist. But by striving to work in a spirit of mutual exchange, with genuine respect and recognition for each other’s experience and gifts, these collaborations are uplifting and beneficial for everyone.

RUHA: There is valid concern about appropriation in the art world. It can and does happen.

One question that has moved to the forefront of my mind since working with Robin is, how can artists from an indigenous culture engage in customary practice alongside people from other cultures as an affirming act of cultural dialogue? I believe it’s possible and important to learn about as an expression of a belief in the oneness of mankind.

But I also recognize that even with the most noble principles and intentions in mind, we must acknowledge that we live in a world where social systems and dominant patterns of thought can perpetuate or normalize exploitative and selfish behavior. We are all influenced by these forces. I feel it is even possible for people to appropriate or exploit their own cultures; we don’t get a free pass just because we have blood ties to a culture.

In this regard, what has been important is to continue to check in myself about the motivations and principles that are driving me. I am realizing that the most appropriate way to engage with indigenous practice is to recognize that it demands individual growth and transformation. This sense of purpose requires of me to be honest and open to understanding my mistakes, figuring out the adjustments that need to be made to my approach and committed to applying those adjustments even if it is less convenient, unseen by others, or takes me down a less familiar or uncomfortable route. An important aspect of this is also seeking to hear and understand the perspectives that differ from my own.

Working with Robin was my first opportunity to be involved in the full process of making a large-scale ngatu. It was an eye-opening experience for me to understand more fully the potency of the practice and the role it plays in nurturing relationships within a community and with the natural environment; facilitating collective reflection, consultation, and knowledge sharing; cultivating unity of purpose, thought, and action; uplifting community ceremonies and gatherings; harmonizing spiritual and scientific sources of knowledge; and harnessing the power of pattern and collectively understood visual languages. It’s these aspects of the practice I am most interested in continuing to explore. How one does this in quickly changing familial and community constructs is a question that I’m finding can only be gradually understood.

INTERVIEWER: Could you describe an example of a collaborative artwork that merged several cultural threads?

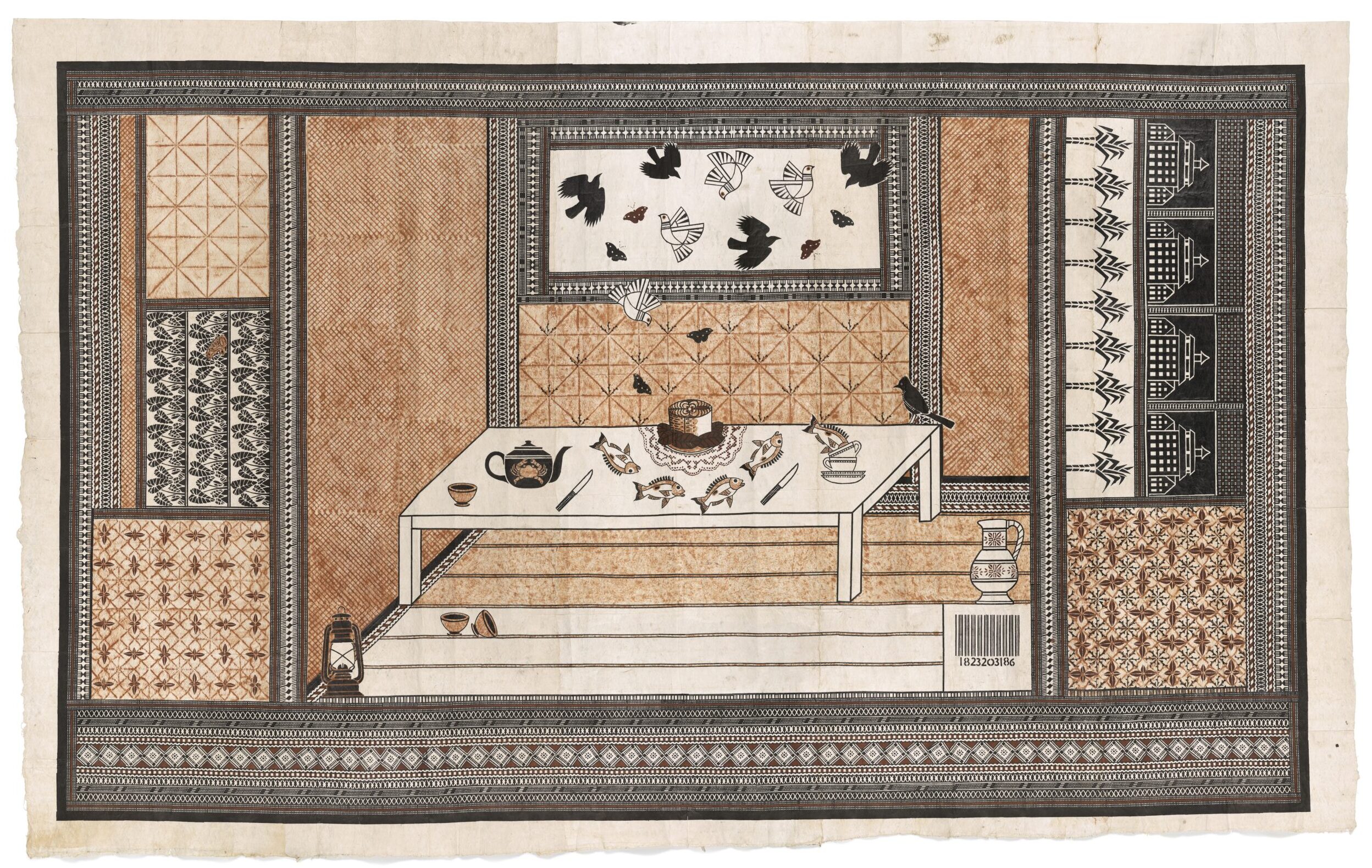

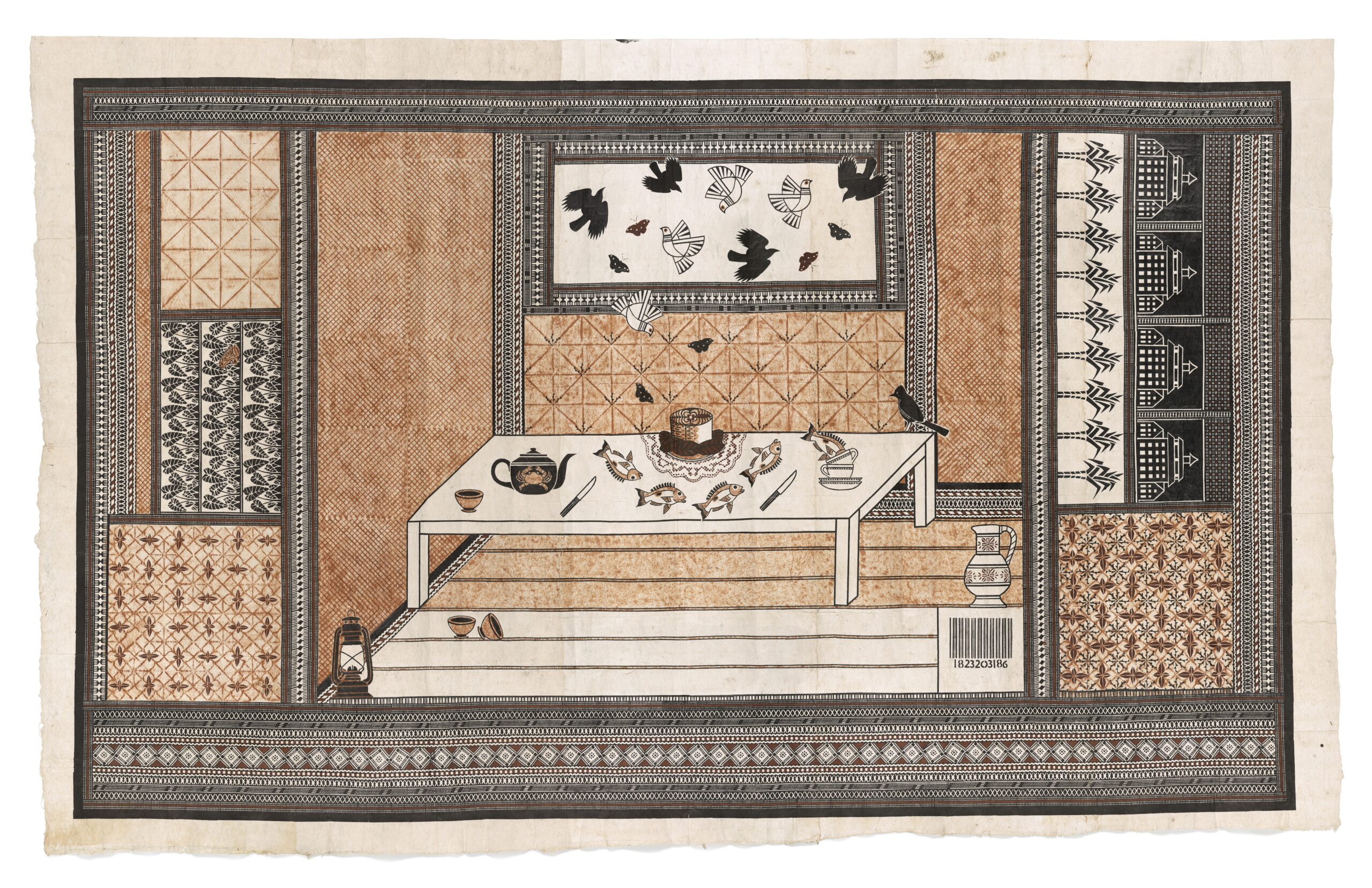

ROBIN: One that stands out is a project in Fiji, which eventually resulted in a piece titled Living in a Material World. It involved me, Ruha, and another collaborator, Tamari Cabeikancea, who is Fijian. We drew on three different bodies of knowledge and experience—Tongan barkcloth, Fijian masi, and my own background and training in the Western art tradition.

I had come to understand from earlier conversations with Tamari and her aunt Leba that in the precolonial times there was a great deal of exchange going on between Tonga and Fiji and that the art of barkcloth reflected a spirit of reciprocity in the sharing of knowledge and skills. A desire grew to explore ways in which we could bring together Tongan and Fijian practitioners to work together to share and combine their traditional skills. Eventually an opportunity presented itself, and I joined Ruha and Tamari in Leba’s home in Lautoka, Fiji, in June 2017.

We began by studying a letter7https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/20170301_001/1#712004157 from the Universal House of Justice, dated 1 March 2017, which prompted us to consider the moral and spiritual dimensions of wealth and economics in the context of core Bahá’í values, such as justice and the oneness of humanity. We reflected on how a consumption-driven culture shapes our lives, and we thought about questions, such as: What is material wealth for? What is the outcome of excessive materialism? What does genuine prosperity look like?

Turning these ideas into a visual art form meant uniting distinct textile processes—an indigenous Fijian approach for the barkcloth base and printed designs, Tongan-inspired patterns layered on top, plus my experience working with composition and color as a painter. Our common ground was that we all shared a spiritual motivation; we were speaking to the same underlying themes.

RUHA: It is important to note we were not introducing intercultural exchange and collaboration as a way of working; this has and does exist within and between all parts of the Pacific region. Artists and creative communities are constantly embracing new opportunities to learn from and with each other through creative practice. For me, what stood out about this experience was the thread of Western arts practice. The points of difference and similarity in the ways Robin thought about composition, tone, symbolism, and function of a work really allowed me to become more conscious of the knowledge and aesthetic principles within the indigenous practices and the questions that might guide my ongoing engagement.

It also helped me to become more aware of two potential benefits of intercultural interactions—one being that it can help us to clarify our own cultural influences and convictions, and the other, that it can raise our consciousness of our agency in the creation and recreation of culture and help strengthen our capacity to exercise this with clarity of purpose and vision.

INTERVIEWER: You’ve mentioned that a lot of consultation and spiritual reflection happens behind the scenes. What did that look like day to day?

RUHA: When working on those first projects with Robin, even when it was just two or three of us working, we would dedicate time each day to reflect and consult. Often, we would do this first thing in the morning, at mealtimes, and at the end of the day.

Every experience of working with others has deepened my appreciation for how fundamental it is to develop a common understanding of the integral role that reflection and consultation play in the art-making process and to purposefully make and protect the time given to this. The more our project or creative process involves complexity or unfamiliar territory, the more time, attention, and care needs to be given to the ways we collectively reflect and consult throughout.

The making of a larger scale work involves many contributors with diverse capacities. Regardless of the level of one’s contribution, making time to build understanding together about the themes within the work, its purpose, and the spiritual qualities and standards it demands has a significant influence on the quality and impact of the final work. Consultation and reflection are also how we can collectively learn from the process, facilitate decision-making, and overcome any challenges or misunderstandings.

Painting and working with one’s hands stimulates a lot of personal reflection, and it is now the norm to always have a notebook handy to record ideas and reflections as they emerge. I enjoy exploring how one can be scientific—experimental, exploratory, analytical, methodical—in one’s approach to developing a creative practice.

ROBIN: Trust and trustworthiness are the essential elements of the whole process. Through these qualities, we can negotiate challenging elements of our collaboration and share opposing opinions constructively and openly. If someone says, “This motif isn’t working,” or “The proportions feel off,” no one interprets it as a criticism, because we’ve built a foundation of love and respect, and we are all striving for excellence. When a project is urgent or large-scale, the spiritual dimension—prayer, reflection, unity—becomes even more important. Without it, the sheer logistics can be overwhelming.

It wasn’t always plain sailing, but if we got blown off course, we’d reflect on why things weren’t working out as hoped for, identify when challenges arose, and remind ourselves that mistakes can be gently remedied and new ideas welcomed. Clarity of purpose is essential and, in that context, so is detachment.

INTERVIEWER: Robin, could you say more about your personal background as an artist and what prompted the shift to this kind of collaborative approach?

ROBIN: In the mid-1960s I went to a university art school in New Zealand and chose to specialize in painting. Then throughout the 1970s and ’80s, I became known for my paintings of New Zealand landscapes and portraits. From the 1970s onwards, my involvement in the Bahá’í community strengthened the core values and the worldview that I had received from my Bahá’í parents and reshaped my sense of how art can be aligned to the needs of society.

A turning point arrived unexpectedly in Kiribati, where in 1982 I had moved with my family. We suffered a devastating house fire that destroyed my studio. My art supplies were lost and there was no local source of replacement. If I wanted to keep creating, I had to adapt to using the available local resources. This led me to considering the use of pandanus8Pandanus refer to the palm-like leaves of pandanus trees. The time-consuming process to prepare them for weaving involves striping away the edges and middle section of the leaves before boiling, soaking, and drying them., which is the material most commonly used by local artisans.

But I had no weaving skills! I turned to women in the community known for their skill in working with pandanus. I laid out my rough sketches, and we embarked on a journey weaving my Western images using their traditional skills.

That experience opened my eyes to the beauty of a truly communal practice. I discovered a joy in working collectively and a deep appreciation of how these customary practices carry spiritual depth. When I later relocated to Aotearoa, I carried that collaborative spirit into subsequent projects, like those with Ruha and her sister Ebonie, and my friends from Fiji—Leba Toki, the late Bale Jone, Tamari Cabeikancea, and her daughter Kesaia Biuvanua.

INTERVIEWER: How does that principle of oneness help you navigate issues of power or authorship in a Western art market that generally focuses on the status of the individual artist?

ROBIN: Provenance is an important matter in the Western art market and authenticity is an issue. So, questions arise like “Who is the artist?” and “Where is the signature?” And if the work sells, “How is income distributed?” There is plenty of room for misunderstandings because, in these tapa9Tapa is a synonym for ngatu. The word “tapa” is used in the Tahiti and the Cook Islands, whereas “ngatu” is used in Tonga. or barkcloth projects, the final work is the result of many hands.

I hope that, over time, those who collect or write about art will appreciate this broader view of authorship. Instead of a single significant figure, they might see a living, collective tapestry of human creativity.

My approach is to be transparent: if a gallerist wants to represent my practice, I explain that, for a collaborative work, I share credit. We name the collaborators; we share proceeds. People in the Western art world sometimes struggle with that concept, but that’s okay. Because of the age difference between myself and Ruha, and my standing in the art world, questions are also raised about what might be perceived as a power imbalance.

RUHA: I remember when Robin first invited me to sign a work I had contributed to. In Tonga, I understood that it was more important for whom or what the ngatu was made to honor rather than who made it, and so any signing or labelling of a work was more to highlight its intended purpose rather than authorship. But Robin’s works were intended for a different context.

It’s helpful for me to draw on the example of an ocean voyage where there needs to be a captain—the one who knows the ocean, knows the destination, and knows how to get there. So, in our collaboration I was like a member of the crew. It was less about imbalance in power and more about what capacity we each had to contribute to the specific goal. I felt that Robin had the deepest understanding about what that goal was, its intended purpose, and the context of the work. Even the way in which the works were signed—I saw this as Robin’s effort to find a way of acknowledging various indispensable contributions.

The most valuable aspect of the collaboration for me was having the opportunity to go through the ngatu-making process from beginning to end for the first time and getting to know and learn from an amazing network of creatives along the way. I really felt that the things I was learning from Robin and others could enrich how I was able to contribute to my own community.

INTERVIEWER: Both of you refer to a kind of evolution in your practice. Where do you see this leading?

RUHA: I’ve loved deepening my appreciation of how indigenous arts practices like ngatu-making exist as an integral part of community life. I see these practices as sophisticated instruments for deep reflection on spiritual, scientific, and social concepts; for generating and sharing knowledge that draws from and nurtures relationships with the natural world and with others; for strengthening our ability to listen, to practice a culture of encouragement, and to uphold standards of excellence; for cultivating unity of thought and action; for responding to practical individual and collective needs; and for elevating significant community events and gatherings. I am most excited when I think of what can be learned by engaging in these kinds of arts practices alongside members of a community that I am a part of, discovering how it can evolve as a collective practice of creative community building and care.

ROBIN: I see my art practice as belonging within a movement that is involving the whole of humanity. I am just a tiny drop in an ocean, and that ocean is moving, carrying all of us through a powerful and irresistible current. The tide is shifting. I think there’s a spiritual awakening in the world that’s nudging people toward a greater appreciation of fellowship and recognition of what we are—one human family, the waves of one ocean. It’s a feeling and a vision that animates my day-to-day reality.

Afterward

In April 2024, the Universal House of Justice expressed its joy at seeing “in every country and region” “true practitioners of peace occupied with building” an “ultimate haven,” and it called for all to “extend then to everyone the hand of friendship, of common endeavor, of shared service, of collective learning, and advance as one.”10https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/20240419_001/1#503426541

Listening to Robin White and Ruha Fifita talk calls to mind this beckoning invitation of the House of Justice. As they reflect on their collaborations, one senses not only their deep mutual respect but also their shared conviction that art can serve as a field of action for building unity. In an era when division and polarization seem to define many societies, the experiences of Robin and Ruha and their art practices provide a hopeful alternative.

Robin and Ruha work with women who do not necessarily call themselves artists but whose skill in weaving or barkcloth-making transcends Western aesthetic categories. Together, these groups of collaborators open their creative process to spiritual reflection—prayer, consultation, moral vision—treating every motif or color choice as an expression of a deeper conversation about humanity’s future.

In bridging so-called traditional and contemporary forms, Robin and Ruha do more than combine mediums. Their experience confirms that our diversity can be a fertile meeting place from which new forms emerge—forms that speak to our shared spiritual identity as one human race.

This approach may not be the norm in a critical art world that sometimes prizes extreme individualism above collective endeavor or views any cross-cultural blending as suspect. Yet Robin and Ruha’s experience offers an alternate vision: that we can honor the living customs of indigenous communities while inviting them to join a global, contemporary dialogue—and that this conversation, if rooted in a reverence for humanity’s oneness, might unlock something new and life-giving for us all.